Abstract

Background

Residency training exposes young physicians to a challenging and high-stress environment, making them vulnerable to burnout. Burnout syndrome not only compromises the health and wellness of resident physicians but has also been linked to prescription errors, reduction in the quality of medical care, and decreased professionalism. This study explored burnout and factors influencing resilience among U.S. resident physicians.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted through an online survey, which was distributed to all accredited residency programs by Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The survey included the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 25), Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory, and socio-demographic characteristics questions. The association between burnout, resilience, and socio-demographic characteristics were examined.

Results

The 682 respondents had a mean CD-RISC score of 72.41 (Standard Deviation = 12.1), which was equivalent to the bottom 25th percentile of the general population. Males and upper-level trainees were more resilient than females and junior residents. No significant differences in resilience were found associated with age, race, marital status, or training program type. Resilience positively correlated with personal achievement, family, and institutional support (p < 0.001) and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

High resilience, family, and institutional support were associated with a lower risk of burnout, supporting the need for developing a resilience training program to promote a lifetime of mental wellness for future physicians.

Keywords: Resident physician, Resilience, Burnout, Survey, National

Background

Post-graduate medical residency training, along with continuing changes in modern healthcare, not to mention the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic, creates a stressful environment and increased risk of burnout. Burnout is defined as a state of mental exhaustion, depersonalization with a decreased sense of personal achievement and is considered a consequence of high levels of stress combined with very ambitious goals [1]. Evidence during the past decade has documented an almost 2-fold increased level of burnout among healthcare providers in comparison to the general working population with more than half of all physicians reporting at least one symptom of burnout [2]. There is a similar prevalence of burnout among resident physicians in general and among medical and surgical residents [3, 4]. Burnout negatively affects many aspects of physicians’ personal and professional lives. Studies have shown that burnout negatively affects the ability to provide quality medical care to patients, including effective communication, demonstration of empathy and establishing therapeutic relationships with patients [5–7]. On a personal level, burnout significantly diminishes personal wellbeing and may even lead to suicide [8–11].

As a response to this concerning situation among residents in training, resilience is receiving more attention because of its potential to positively influence health and wellbeing and counter the negative effects of burnout [2, 12]. Resilience is recognized as an indicator of psychological maturity [13, 14] and can help residents to cope with the stress inherent in training and their subsequent lives as physicians. Resilient individuals deal more effectively with adversity and the challenges of high workload and high expectations which are characteristics of the medical profession [15–18]. Improving resilience, therefore, can be expected to decrease the development and negative sequel of burnout.

We wished to examine burnout and resilience among U.S. resident physicians in the United States by quantifying the degree of burnout and resilience as well as identifying the demographic and work-related characteristics that are predictive of burnout.

Methods

A cross-sectional study using an online survey was conducted from November 2018 to January 2019. An email invitation to participate in the survey was sent to all residency training program directors and/or program coordinators listed online by Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database (FREIDA™) in the United States requesting that they forward the survey link to their residents. The email also included a cover letter to the residents asking for their voluntary participation, explaining the confidentiality of results, and providing a hyperlink to the survey. The respondents completed a baseline questionnaire online that included general demographic information, the Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory (AMBI), the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), questions on compliance with ACGME 80 h duty restrictions, and institutional and family support. The AMBI [19] is an introspective and validated psychological inventory consisting of 9-items pertaining to occupational burnout and incorporates three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal achievement (PA). All AMBI items are scored using a 7-level frequency scale from “never” (0) to “daily” (6). A high score on EE and DP associated with a low score on PA indicates a high level of burnout. The 25-item version of CD-RISC was used to measure resilience [20]. Respondents indicated their level of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (4). The total score was calculated by adding all responses and thus ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience. The response for family support and compliance with 80 h restriction were using 5-point Likert scale from “never” (1) to “always” (5). The 5-point Likert scale assigned for responses on questions related to job satisfaction including “considering all of this I like my job”, “there is a positive morale at work”, “this hospital is a good place to work”, “I am proud to work at this hospital” and “during my residency I feel like being part of a large family” was from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). The response on “number of hours of sleep” used 4-point Likert scale from “4 or fewer hours (4)” to 9 or more hours (1)”. The response on “how comfortable do you feel making autonomous decision in care for the patient” was in 5-point Likert scale from “Not at all comfortable” (1) to “extremely comfortable” (5). The 5-point Likert scale assigned for responses on “how satisfied are you with faculty involvement in your education?” was from “very dissatisfied” (1) to “very satisfied” (5). The response on “the level of supervision during your current year of training” is using 5-point Likert scale from “no supervision” (1) to “direct supervision” (5). We chose a margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95% to assess the response rate as adequate with a calculated minimal sample size of 383. The population size was estimated using Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) 2019 residency report.

The study was approved by our local Institutional Review Board and the anonymity of the respondents was fully protected with no personal nor program identifiers being collected. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software [IBM Corp, Armonk, NY]. Proportions and frequencies were calculated for categorical variables while means and standard deviation were computed for continuous variables. Comparisons of mean CD-RISC on different groups in gender, age, ethnicity, and relationship in Table 1 were made using one-way ANOVA, respectively. The correlations between CD-RISC and factors of interest were examined by Pearson’s correlation coefficient in Table 3. Multiple linear regression modeled the association between demographic variables and CD-RISC, personnel achievement, emotional exhaustion and depersonalized, respectively. The results were summarized in Table 4. The model assumptions for one-way ANOVA and multiple linear regression were examined and satisfied. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents

| Variable | n | % | CD-RISCa (Mean + SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 383 | 56 | 71 + 12 | 0.014 |

| Male | 299 | 44 | 74 + 13 | ||

| Age (years) | Younger than 35 | 601 | 88 | 72 + 12 | 0.093 |

| 35 or older | 81 | 12 | 75 + 13 | ||

| Ethnicity | Caucasians | 458 | 67 | 73 + 12 | 0.107 |

| Asian / Pacific Islander | 113 | 17 | 71 + 13 | ||

| Hispanic | 47 | 7 | 75 + 12 | ||

| Multiple ethnicity / Other | 36 | 5 | 69 + 11 | ||

| African American | 27 | 4 | 74 + 9 | ||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 | < 1 | |||

| Relationship | Married/ Partnership | 452 | 66 | 73 + 12 | 0.560 |

| Single, never married | 208 | 31 | 71 + 12 | ||

| Separated/ Divorced/ Widow | 22 | 3 | 73 + 10 | ||

| Training Level | PGY 1 | 167 | 25 | 72 + 12 | 0.037 |

| PGY 2 | 178 | 26 | 71 + 12 | ||

| PGY 3 | 174 | 26 | 72 + 12 | ||

| PGY 4 | 107 | 16 | 74 + 12 | ||

| PGY 5 | 34 | 5 | 74 + 9 | ||

| PGY 6 | 8 | 1 | 84 + 5 | ||

| PGY 7 | 5 | < 1 | 78 + 10 | ||

| PGY 8 | 9 | 1 | 78 + 19 | ||

| Type of Program | University Hospital | 419 | 61 | 73 + 12 | 0.132 |

| Community Hospital | 230 | 34 | 71 + 13 | ||

| Other | 33 | 5 | 72 + 11 | ||

| Geographic Location | Territory (PR) | 2 | < 1 | 93 + 0 | 0.057† |

| West | 84 | 12 | 72 + 13 | ||

| South | 188 | 28 | 74 + 12 | ||

| Mid-West | 204 | 30 | 72 + 12 | ||

| North-East | 204 | 30 | 71 + 12 |

aCD-RISC Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

†excluded Territory (PR)

Table 3.

Associations between factors and resilience (Pearson correlation of CD-RISC) (n = 682)

| Factors | Factor-resilience relationship | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | |

| Family support | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Considering all of this I like my job | 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Compliance with 80 h restriction | 0.13 | < 0.001 |

| Personal achievement | 0.48 | < 0.001 |

| Emotional exhaustion | −0.48 | < 0.001 |

| Depersonalization | − 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| Number of hours of sleep | −0.01 | 0.720 |

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression analysis of variables relating resilience, personal achievement, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization

| Source | CD-RISC | Personal Achievement | Emotional Exhaustion | Depersonalization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | p-value | Beta | p-value | Beta | p-value | Beta | p-value | |

| CD-RISC | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.02 | < 0.001 | −0.01 | 0.017 | ||

| Family support | 1.85 | <0.001 | −0.04 | 0.282 | 0.03 | 0.405 | < −0.01 | 0.914 |

| Autonomy | 3.47 | <0.001 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.691 | 0.01 | 0.837 |

| Considering everything I like my job | 4.66 | <0.001 | 0.22 | <0.001 | −0.29 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.003 |

| Surgical Specialties | ||||||||

| Non-Surgical | −3.31 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.652 | −0.07 | 0.427 |

| Surgical | Reference | |||||||

| Geography | 0.007 | 0.838 | 0.807 | 0.104 | ||||

| Mid-West | −0.50 | 0.689 | −0.01 | 0.953 | 0.04 | 0.669 | 0.01 | 0.928 |

| North-East | −0.72 | 0.565 | 0.04 | 0.698 | −0.03 | 0.790 | −0.17 | 0.153 |

| South | 2.43 | 0.055 | −0.04 | 0.726 | −0.02 | 0.823 | −0.17 | 0.147 |

| West | Reference | |||||||

| I am proud to work at this hospital | 0.94 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.305 | −0.1 | 0.041 | −0.13 | 0.022 |

| There is a positive morale at work | 0.95 | 0.107 | <0.01 | 0.972 | −0.15 | 0.001 | −0.01 | 0.856 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | −1.16 | 0.127 | 0.12 | 0.082 | 0.09 | 0.124 | −0.43 | <0.001 |

| Male | Reference | |||||||

| Marital Status | 0.331 | 0.102 | 0.073 | 0.488 | ||||

| Married | −1.21 | 0.152 | −0.14 | 0.066 | −0.15 | 0.026 | −0.05 | 0.531 |

| Separated | −1.69 | 0.446 | 0.11 | 0.579 | −0.01 | 0.957 | −0.24 | 0.250 |

| Single | Reference | |||||||

| Type of program | 0.332 | 0.751 | 0.887 | 0.543 | ||||

| Community | −0.62 | 0.458 | −0.05 | 0.540 | 0.02 | 0.76 | −0.09 | 0.269 |

| Other | −2.41 | 0.168 | 0.05 | 0.726 | 0.06 | 0.673 | −0.02 | 0.899 |

| University | Reference | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 35 and older | 1.51 | 0.201 | 0.15 | 0.156 | −0.05 | 0.575 | −0.23 | 0.034 |

| Younger than 35 | Reference | |||||||

| Race | 0.396 | 0.681 | 0.010 | 0.006 | ||||

| African American | 1.27 | 0.515 | −0.05 | 0.762 | −0.05 | 0.747 | −0.55 | 0.002 |

| American Indian | 2.80 | 0.773 | 0.24 | 0.776 | 0.54 | 0.49 | −0.40 | 0.662 |

| Asian | −0.75 | 0.469 | −0.13 | 0.164 | −0.27 | 0.001 | −0.09 | 0.379 |

| Hispanic | 2.04 | 0.174 | −0.14 | 0.296 | −0.14 | 0.249 | −0.35 | 0.012 |

| Other | −2.29 | 0.173 | −0.13 | 0.396 | 0.19 | 0.153 | 0.14 | 0.368 |

| Caucasians | Reference | |||||||

| Satisfaction with faculty | 0.18 | 0.723 | 0.02 | 0.718 | −0.04 | 0.320 | −0.02 | 0.660 |

| Supervision | −0.80 | 0.109 | 0.04 | 0.404 | 0.04 | 0.312 | 0.04 | 0.385 |

| This hospital is a good place to work | 0.41 | 0.507 | <0.01 | 0.982 | −0.05 | 0.281 | −0.12 | 0.039 |

| Compliance with 80 h rule | 0.44 | 0.381 | −0.04 | 0.368 | −0.06 | 0.132 | 0.03 | 0.568 |

| During my residency I feel being part of a big family | −0.01 | 0.834 | 0.04 | 0.303 | 0.02 | 0.591 | 0.03 | 0.550 |

Results

There was a total of 848 survey respondents. Of these respondents, 682 (81%) completed all the questions and were thus used for further data analysis. This response rate surpassed our calculated minimal sample size requirement of 383. The demographic details about the participants are presented in Table 1.

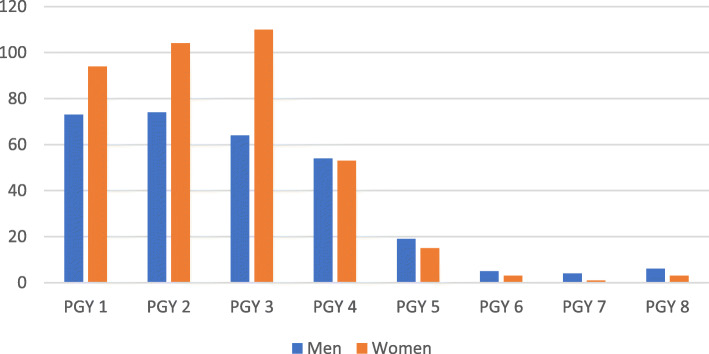

The responders had almost equal gender distribution female (N = 383, 56%) as compared to male (N = 299, 44%). The majority (N = 601, 88%) were in 25–34 years of age, Caucasians (N = 458, 67%), and married or in a long-term partnership (N = 452, 66%). Gender distribution among training level is depicted in Fig. 1 and reflects the increasing number of graduating medical students, and subsequently residents, being female.

Fig. 1.

Gender distribution across post graduate year (PGY) training levels. Males labeled in blue, females labeled in orange. PGY1 = residents in first year of postgraduate training, PGY2 = residents in the second year of postgraduate training, PGY3 = residents in the third year of postgraduate training, PGY4 = residents in the fourth year of postgraduate training, PGY5 = residents in the fifth year of postgraduate training, PGY6 = residents in the sixth year of postgraduate training, PGY7 = residents in the seventh year of postgraduate training, PGY8 = residents in the eighth year of postgraduate training

Table 2 describes the specialty distribution of the survey respondents. Three quarters, (N = 509, 75%) were in medical specialties while the remainder were surgical residents. A comparison of all residents, reflected in the 2019 AAMC resident distribution by specialty data, indicates that the respondents on the survey were broadly representative of all residents in the U.S.

Table 2.

Specialty distribution of respondents versus all residents in U.S

| Specialty | Survey Respondents | 2019 AAMC Data | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | % | Female | % | Total | Male | % | Female | % | Total | |

| Anesthesiology | 22 | 56 | 17 | 44 | 39 | 4023 | 66 | 2034 | 34 | 6057 |

| Child Neurology | 2 | 22 | 7 | 78 | 9 | 123 | 32 | 266 | 68 | 389 |

| Dermatology | 3 | 50 | 3 | 50 | 6 | 562 | 39 | 877 | 61 | 1439 |

| Diagnostic Radiology-Nuclear Medicine | 4 | 50 | 4 | 50 | 8 | 4 | 67 | 2 | 33 | 6 |

| Emergency Medicine | 31 | 61 | 20 | 39 | 51 | 4941 | 65 | 2720 | 36 | 7661 |

| Emergency Medicine-Family Medicine | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 18 | 50 | 18 | 50 | 36 |

| Family Medicine | 17 | 32 | 37 | 69 | 54 | 5735 | 46 | 6663 | 54 | 12,398 |

| Family Medicine-Preventive Medicine | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 50 | 10 | 50 | 20 |

| Internal Medicine | 21 | 46 | 25 | 54 | 46 | 15,389 | 58 | 11,284 | 42 | 26,673 |

| Internal Medicine-Emergency Medicine | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 2 | 85 | 64 | 47 | 36 | 132 |

| Internal Medicine-Medical Genetics | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 1 | 20 | 5 |

| Internal Medicine-Pediatrics | 4 | 29 | 10 | 71 | 14 | 606 | 41 | 874 | 59 | 1480 |

| Internal Medicine-Preventive Medicine | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 48 | 15 | 52 | 29 |

| Internal Medicine-Psychiatry | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 56 | 53 | 49 | 47 | 105 |

| Interventional Radiology-Integrated | 2 | 40 | 3 | 60 | 5 | 172 | 80 | 43 | 20 | 215 |

| Medical Genetics and Genomics | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 22 | 34 | 43 | 66 | 65 |

| Neurology | 9 | 69 | 4 | 31 | 13 | 1516 | 55 | 1266 | 46 | 2782 |

| Neurological Surgery | 9 | 82 | 2 | 18 | 11 | 1218 | 83 | 259 | 18 | 1477 |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 7 | 12 | 54 | 89 | 61 | 886 | 17 | 4495 | 84 | 5381 |

| Ophthalmology | 8 | 47 | 9 | 53 | 17 | 794 | 60 | 538 | 40 | 1332 |

| Orthopedic Surgery | 18 | 75 | 6 | 25 | 24 | 3353 | 85 | 610 | 15 | 3963 |

| Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery | 2 | 40 | 3 | 60 | 5 | 1025 | 64 | 581 | 36 | 1606 |

| Pathology -Anatomic and Clinical | 4 | 31 | 9 | 69 | 13 | 1125 | 50 | 1120 | 50 | 2245 |

| Pediatrics | 19 | 25 | 57 | 75 | 76 | 2461 | 28 | 6419 | 72 | 8880 |

| Pediatrics-Anesthesiology | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 34 | 25 | 66 | 38 |

| Pediatrics-Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 2 | 17 | 10 | 83 | 12 |

| Pediatrics-Psychiatry-Child and Adolescent Psychiatry | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 22 | 24 | 71 | 76 | 93 |

| Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | 8 | 57 | 6 | 43 | 14 | 843 | 63 | 503 | 37 | 1346 |

| Plastic Surgery | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 142 | 69 | 63 | 31 | 205 |

| Plastic Surgery-Integrated | 1 | 33 | 2 | 67 | 3 | 524 | 59 | 372 | 42 | 896 |

| Preventive Medicine | 4 | 50 | 4 | 50 | 8 | 142 | 49 | 146 | 51 | 288 |

| Psychiatry | 21 | 35 | 39 | 65 | 60 | 2934 | 50 | 2943 | 50 | 5877 |

| Psychiatry-Family Medicine | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | 4 | 18 | 35 | 33 | 65 | 51 |

| Radiation Oncology | 10 | 67 | 5 | 33 | 15 | 519 | 70 | 225 | 30 | 744 |

| Radiology-Diagnostic | 12 | 44 | 15 | 56 | 27 | 3194 | 73 | 1178 | 27 | 4372 |

| Surgery - General | 21 | 53 | 19 | 48 | 40 | 5384 | 59 | 3789 | 41 | 9173 |

| Thoracic Surgery-Integrated | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 158 | 73 | 59 | 27 | 217 |

| Transitional Year | 8 | 57 | 6 | 43 | 14 | 798 | 63 | 464 | 36 | 1262 |

| Urology | 14 | 74 | 5 | 26 | 19 | 1009 | 75 | 342 | 25 | 1351 |

| Vascular Surgery-Integrated | 5 | 71 | 2 | 0.3 | 7 | 212 | 67 | 107 | ,34 | 319 |

| Total | 299 | 44 | 383 | 56 | 682 | 60,056 | 54 | 50,564 | 46 | 110,620 |

Descriptive statistics for the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale showed a mean value of 72 with a median of 72 and a mode of 65. There were no significant differences in CD-RISC scores based on age, ethnicity, or marital status (Table 1). However, female residents were significantly less resilient (F = 6.103, p = 0.014) when compared to their male counterparts, with a score of 71 and 74, respectively.

No significant differences in resilience were found among participants from academic versus community hospital-based training program (F = 2.031, p = 0.132) or geographic regions (F = 2.522, p = 0.057). The residents in the upper level of training had significantly higher CD-RISC scores when compared to the junior residents (F = 2.145, p = 0.037) with residents from postgraduate years six to eight (PGY 6–8) being the most resilient with CD-RISC = 80.1 (13.4), followed by the residents from postgraduate year four and five (PGY 4–5) with CD-RISC = 74.1(11.3) and postgraduate year one to three (PGY 1–3) with CD-RISC = 71.6 (12.5).

Specialty distribution was also not found to be correlated to with resilience (F = 1.176, p = 0.250). However, when comparing the medical and surgical specialties, surgical residents scored higher in resilience than medical residents (F = 7.169, p = 0.008; CD-RISC = 74.5 (11.5) versus 71.7 (12.3).

There was a significant and positive correlation between family support and higher resilience (r = 0.28, p < 0.001; Table 3).

Residents with strong family support (always, usually) scored higher than the residents with sporadic or inexistent family support (sometimes, rarely, never). Job satisfaction and residency program support was assessed through five questions and was also found to correlate positively with resilience. There is a positive correlation with the self-affirmation “Considering everything I like my job “(r= 0.50, p< 0.001), “There is a positive morale at work“ (r= 0.39, p<0.001), “This hospital is a good place to work“ (r=0.36, p<0.001), “I am proud to work at this hospital“ (r= 0.37, p<0.001)”, and “During my residency I feel like being part of a large family” (r = 0.33, p < 0.001). No correlation was found between the resilience index and the number of hours of sleep (r = − 0.01, p = 0.720), however the compliance with the 80-h restriction was a small but significant correlate (r = 0.13, p < 0.001).

Multiple linear regression showed five significant factors associated with higher resilience (Table 4): family support, geographic location, surgical specialties, autonomy, and agreeing to the question “Considering everything, I like my job“.

The average CD-RISC score for residents increased by 1.85 points for every one-point increase in Likert scale in family support. The average CD-RISC score for residents increased by 3.47 points for every one-point increase in Likert scale in comfortable being autonomous in making medical decisions. For every one-point increase in Likert scale regarding the question” Considering everything, I like my job”, the average CD-RISC score increases by 4.66 points. Overall, 64% of the respondents were found to have at least one element of burnout with predominance on emotional exhaustion (58%). Resilience positively correlates with the sense of personal achievement (r = 0.484, p < 0.001) and negatively with emotional exhaustion (r = − 0.477, p < 0.001) and depersonalization (r = − 0.305, p < 0.001).

Each element of burnout was examined using multiple linear regression. Personal achievement was positively corelated with autonomy, “Considering everything, I like my job”, and having higher resilience score. Emotional exhaustion had five significant factors: race, disagreeing with the questions “Considering everything, I like my job,” “There is a positive morale at work,” “I am proud to work at this hospital,” and a low CD-RISC. The emotional burnout for White/Caucasians residents was higher than that for Asian/Pacific islander residents (p < 0.001). Although not significant in the multiple linear regression analysis, the emotional exhaustion for residents that were “single/never married” was higher than that for “married/in a partnership” residents (p = 0.026).

We found six significant factors in the multiple linear regression analysis influencing depersonalization: resident under age 35 years (p = 0.034), male gender (p < 0.001), race (p = 0.006), lower CD-RISC (p = 0.017), disagreeing with “Considering everything, I like my job” (p = 0.003), and “This hospital is a good place to work” (p = 0.039). Caucasians residents reported higher depersonalization when compared to Hispanics (p = 0.012) and African Americans residents (p = 0.002).

Discussion

This study was conducted based on the premise that resident physicians must navigate a complex, contradictory, and stressful environment which makes them vulnerable to burnout. There is ample literature supporting the concept that resilience is inversely correlated with burnout [5, 21, 22]. In addition, there is genuine concern among academic faculty that there is decreasing resilience among graduate and post-graduate students in the United States that extends to resident physicians. By extension, residents with higher levels of resilience would be expected to better cope and adapt to the stresses of residency. Our study examined to what degree this expectation is correct.

In the original Connor and Davidson 2003 study, mean CD-RISC scores for the U.S. general population was 81, with quartile percentile distribution for Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 being 0–73, 74–82, 83–90, 91–100 [20]. In comparison, score means for primary care patients and psychiatric outpatients were 72 and 68, respectively. In this context, the resident physician participants from this study had a median of 72, placing them in the lowest 25% of the general population and at a similar level to older primary care patients. Our results are also similar to a prior study that examined resilience in interns [21].

Our results did not demonstrate any difference in CD-RISC resilience scores based on age, marital status, or ethnicity. This is consistent with the findings summarized by Davidson [23].

and in the general U.S. population [20]. There were, however, gender differences. We found that male resident physicians were more resilient than females (CD-RISC score of 74 vs 71). Such gender differences vary among different populations and is inconsistent. Connor found no gender differences in the general population [20] but among medical students, male had higher resilience scores than female in both Canadian [24] and U.S. medical students [25]. Perhaps reflecting a selection bias, female Air Force recruits were more resilient than male [26].

No significant resiliency differences were found among participants from different types of training programs (academic vs. non-academic), specialty or geographic regions. No prior published literature has focused on these characteristics. Although age was not a significant factor for resilience, as also noted in other groups [20, 27] the level of training was. Upper-level residents were more resilient than junior residents. PGY 1–3 had CD-RISC scores corresponding to the 25th percentile of the U.S. population while PGY 4–5 improved to the level of the 50th percentile and those in PGY 6–8 were close to 75th percentile. These findings suggest that resilience does not increase with age but rather is enhanced by experience and speaks of the positive effect of the residency training environment.

Family support and friends had a significant and positive effect on increasing resilience, as also seen in other populations [7, 28, 29]. In addition, resilience positively correlated with personal achievement (p < 0.001) and negatively with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (p < 0.001). Similar evidence is found in the literature [25, 30–33] and suggests that interventions addressing these areas can improve resilience during residency and thus prevent burnout in our trainees.

Almost two thirds of the survey respondents had at least one element of burnout with a predominance reporting emotional exhaustion. Previously, others had reported burnout from 40 to 75% among U.S. residents [25] comparable with global burnout prevalence of over 50% in other populations [25]. We further found that being single was associated with emotional exhaustion and Caucasians experienced more emotional exhaustion and depersonalization than other ethnic groups.

Our study has several limitations. Although the number of respondents was almost double the required minimum sample size, the overall response rate was low. This is explained by program contact information that was not 100% accurate so that some of the survey requests did not reach their destination. Without direct contact information for the individual residents, we relied on the program directors or coordinators to forward the survey to their trainees, which may not have occurred in many cases due to the large number of survey requests being sent out to programs. The response rate from various groups representing ethnicity, geographic location, and specialties is challenging to calculate but appears to reflect the national AAMC data. Future studies, such as the ACGME directed survey, could include more extensive resilience and burnout inventory scales. Nonetheless, our results are consistent with other studies and suggest foci for attention to increase resilience and decrease burnout in our resident physicians.

Conclusions

This study brings compelling evidence that resilience development should be done not only by teaching individuals to be resilient but also by developing the infrastructure and institutional protective support system against burnout in healthcare providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the program directors, resident physicians, and program coordinators who facilitated and completed the survey.

Abbreviations

- ACGME

Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education

- AMBI

Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

- CD-RISC 25

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

- DP

Depersonalization

- EE

Emotional Exhaustion

- FREIDA™

Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database

- IBM Corp

International Business Machines Corporation

- PA

Personal Achievement

- PGY 6–8

Postgraduate Year six to eight

- PGY 4–5

Postgraduate Year four and five

- PGY 1–3

Postgraduate Year one to three

- SPSS

Statistical Product and Service Solution

Authors’ contributions

CN contributed to study design, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. OAB contributed to study design, acquisition of data, and writing of the manuscript. JB contributed to the interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, and revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. CIC contributed to statistical analysis and data interpretation. GJS contributed to the conception and design of the study. All authors read and reviewed the final version of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research and Study Abroad of Dr. Bota were funded by the University of Transylvania’s academic faculty research grant.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not immediate available due to technical support availability but it is freely obtainable from the corresponding author on request, given reasonable time to obtain the necessary technical support.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, Inspira Medical Center, Vineland, NJ, USA. The administrative staff member and IRB Chair determined that the study submission was exempt from IRB review in accordance with the Federal Code of Regulations. The informed consent was waived because the study was a survey that involved minimal risk to the participants and the researchers did not have access to identifiable data. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations in the Ethical Declarations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nazir A, Smalbrugge M, Moser A, Karuza J, Crecelius C, Hertogh C, Feldman S, Katz PR. The prevalence of burnout among nursing home physicians: an international perspective. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(1):86–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, West CP. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, Herrin J, Wittlin NM, Yeazel M, Dovidio JF, Cunningham B, White RO, Phelan SM, Satele DV, Shanafelt TD, van Ryn M. Association of Clinical Specialty with Symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1114–1130. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, Leung GK, McIntyre RS, Guerrero A, Lu B, Sin Fai Lam CC, Tran BX, Nguyen LH, Ho CS, Tam WW, Ho RC. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(9):1479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montero-Marin J, Tops M, Manzanera R, Piva Demarzo MM, Álvarez de Mon M, García-Campayo J. Mindfulness, resilience, and burnout subtypes in primary care physicians: the possible mediating role of positive and negative affect. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1895. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheepers RA, Boerebach BC, Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. A systematic review of the impact of Physicians' occupational well-being on the quality of patient care. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(6):683–698. doi: 10.1007/s12529-015-9473-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Card AJ. Physician burnout: resilience training is only part of the solution. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):267–270. doi: 10.1370/afm.2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks-Savage A, Archer L, Newton H, Wheeler E, Huband SR. Prevention of medical errors and malpractice: is creating resilience in physicians part of the answer? Int J Law Psychiatry. 2018;60:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, Lewith G, Kontopantelis E, Chew-Graham C, Dawson S, van Marwijk H, Geraghty K, Esmail A. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker K, Sen S. Healing Medicine's future: prioritizing physician trainee mental health. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(6):604–613. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.6.medu1-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. Nurturing resiliency in medical trainees. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloninger CR, Zohar AH. Personality and the perception of health and happiness. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(1–2):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cloninger CR, Salloum IM, Mezzich JE. The dynamic origins of positive health and wellbeing. Int J Person Cent Med. 2012;2(2):179–187. doi: 10.5750/ijpcm.v2i2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrman H, Stewart DE, Diaz-Granados N, Berger EL, Jackson B, Yuen T. What is resilience? Can J Psychiatr. 2011;56(5):258–265. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eley DS, Cloninger CR, Walters L, Laurence C, Synnott R, Wilkinson D. The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: implications for enhancing well being. PeerJ. 2013;1:e216. doi: 10.7717/peerj.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein RM, Krasner MS. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):301–303. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280cff0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morice-Ramat A, Goronflot L, Guihard G. Are alexithymia and empathy predicting factors of the resilience of medical residents in France? Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:122–128. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5ac6.44ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaikh AA, Shaikh A, Kumar R, Tahir A. Assessment of burnout and its factors among doctors using the abbreviated Maslach burnout inventory. Cureus. 2019;11(2):e4101. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laff R. Depression and resilience during the first six-months of internship. Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library 2009. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/429/ . Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

- 22.Lebares CC, Hershberger AO, Guvva EV, Desai A, Mitchell J, Shen W, Reilly LM, Delucchi KL, O’Sullivan PS, Ascher NL, Harris HW. Feasibility of formal mindfulness-based stress-resilience training among surgery interns: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(10):e182734. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.JRT. D. Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Manual. 2018. http://www.connordavidson-resiliencescale.com/CD-RISC%20Manual%2008-19-18.pdf . Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

- 24.Rahimi B, Baetz M, Bowen R, Balbuena L. Resilience, stress, and coping among Canadian medical students. Can Med Educ J. 2014;5(1):e5–12. doi: 10.36834/cmej.36689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houpy JC, Lee WW, Woodruff JN, Pincavage AT. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1320187. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1320187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bezdjian S, Schneider KG, Burchett D, Baker MT, Garb HN. Resilience in the United States air Force: psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Psychol Assess. 2017;29(5):479–485. doi: 10.1037/pas0000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu DWY, Fairweather-Schmidt AK, Burns RA. The Connor-Davidson resilience scale: establishing invariance between gender across the lifespan in a large community based study. J Psychopathol Behav. 2015;37(2):340–348. doi: 10.1007/s10862-014-9452-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheshire A, Ridge D, Hughes J, Peters D, Panagioti M, Simon C, Lewith G. Influences on GP coping and resilience: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(659):e428–e436. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X690893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winkel AF, Robinson A, Jones AA, Squires AP. Physician resilience: a grounded theory study of obstetrics and gynaecology residents. Med Educ. 2019;53(2):184–194. doi: 10.1111/medu.13737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arrogante O, Aparicio-Zaldivar E. Burnout and health among critical care professionals: the mediational role of resilience. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;42:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson K, Kemper KJ, Mahan JD. What factors promote resilience and protect against burnout in first-year pediatric and medicine-pediatric residents? J Evidence Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20(3):192–198. doi: 10.1177/2156587214568894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bird A-N, Pincavage AT. Initial characterization of internal medicine resident resilience and association with stress and burnout. J Biomed Educ. 2016;2016:4. doi: 10.1155/2016/3508638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moffatt-Bruce SD, Nguyen MC, Steinberg B, Holliday S, Klatt M. Interventions to reduce burnout and improve resilience: impact on a health System's outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62(3):432–443. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not immediate available due to technical support availability but it is freely obtainable from the corresponding author on request, given reasonable time to obtain the necessary technical support.