Abstract

Mycobacterium malmoense is an opportunistic human pathogen of increasing clinical importance. Since it is difficult to detect and identify the organism by conventional techniques, it was decided to seek a nucleic acid amplification method specific for M. malmoense. The method was based on detection of a conserved band in random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprints of 45 M. malmoense strains. This band was a 1,046-bp product which was proven to be M. malmoense specific in dot blot hybridization analysis with a panel of mycobacterial strains belonging to 39 other species. The fragment was sequenced, and oligonucleotide primers were synthesized to evaluate the specificity of the PCR. Two primer pairs were found to be specific and sensitive in the nested PCR that was developed. All 49 M. malmoense strains analyzed produced a PCR product of the expected size. In contrast, no strains belonging to the other mycobacterial species tested produced amplicons with these primers under specified reaction conditions. The results of the electrophoresis were confirmed by the hybridization with the M. malmoense-specific oligonucleotide probe. This method could be applied to the analysis of clinical or environmental samples, permitting the rapid detection of M. malmoense.

Mycobacterium malmoense is a potential human pathogen which causes infections similar to those caused by the Mycobacterium avium complex (9, 14). It has steadily increased in clinical importance in the Nordic countries and Scotland (3, 7, 20), and recently, it has also been isolated from clinical samples in other countries (32). M. malmoense has also been detected in natural environments (11, 23, 26). M. malmoense is a difficult species to isolate (8, 12, 13), and its identification may also be problematic by conventional identification tests (34). Analytic techniques based on lipid profiles or gene sequencing have been found to be more reliable for its identification (21, 28, 33).

Several PCR-based methods have been developed for the detection and/or identification of atypical mycobacteria. In these techniques, a number of primers may be used (multiplex PCR [18]) or a selected conserved region of the genome is amplified, and the recognition of the species is based on the detection of differences in some bases in the amplified sequence. In the latter case, the final species identification is based on the analysis of the amplicon by nucleic acid sequencing (17, 28), restriction endonuclease digestion (4, 19, 35), or nucleic acid hybridization (29, 30).

The genome of M. malmoense is poorly characterized. No published information on M. malmoense-specific genes is available. The data published so far comprise data for species-specific portions of the genome that are only a few bases in length (6, 28). One useful way to discover longer species-specific parts in a sequence of a microbe whose genomic data are unknown is to perform fingerprint profile analysis of several strains belonging to the same species (22). We applied this method to the analysis of M. malmoense for species-specific sequences which could be used as targets for an M. malmoense-specific PCR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The following Mycobacterium type strains were included in the study: M. agri ATCC 27406 (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Rockville, Md.), M. aichiense ATCC 27280, M. asiaticum ATCC 25276, M. austroafricanum ATCC 33464, M. avium ATCC 15769, M. branderi ATCC 51788 and ATCC 51789, M. celatum I ATCC 51130, M. celatum II ATCC 51131, M. chitae ATCC 19627, M. chubuense ATCC 27278, M. cookii ATCC 49103, M. diernhoferi ATCC 19340, M. fallax ATCC 35219, M. flavescens ATCC 14474, M. fortuitum ATCC 35754, ATCC 6841, and ATCC 6842, M. gastri ATCC 15754, M. gordonae ATCC 14470, M. hiberniae ATCC 49874, M. interjectum ATCC 51457, M. intermedium ATCC 51848, M. intracellulare ATCC 13950, M. kansasii ATCC 12478, M. komossense ATCC 33013, M. marinum ATCC 927, M. malmoense ATCC 29571, M. neoaurum ATCC 25795, M. nonchromogenicum ATCC 19530, ATCC 19533, and ATCC 35783, M. peregrinum ATCC 14467, M. phlei ATCC 12298, M. pulveris ATCC 35154, M. scrofulaceum ATCC 19981 and ATCC 35792, M. shimoidei ATCC 27962, M. simiae ATCC 25275, M. smegmatis ATCC 35797, M. sphagni ATCC 33027, M. szulgai ATCC 35799, M. terrae ATCC 15755, M. triviale ATCC 23291, M. tuberculosis ATCC 25177 and ATCC 27294 (H37Rv), and M. xenopi ATCC 19250. M. bovis BCG 965/Gothenburg (vaccine strain) was a gift from M. Riddel, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Two strains, M. chelonae QC500/91 and M. haemophilum QC190/91, that were distributed in an Australian quality control scheme were gifts from A. Marzec, Austin Hospital, Melbourne, Australia. The following clinical isolates from the culture collection of the Department of Clinical Microbiology, Kuopio University Hospital, were included: M. bovis BCG (one strain), M. chelonae subsp. abscessus (one strain), and M. malmoense (39 Finnish and 6 British strains) (10). In addition, three Finnish environmental isolates of M. malmoense that originated from stream water were included (11).

The strains were stored at −70°C in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). For the present study, the strains were grown on Middlebrook 7H11 agar with Middlebrook OADC (oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, catalase) enrichment (Difco Laboratories). If necessary, the identity of a strain was reconfirmed by fatty acid analysis by gas-liquid chromatography complemented with a panel of biochemical tests previously described in detail (10, 31).

For DNA extraction, all mycobacteria except M. haemophilum were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth at 37°C; M. haemophilum was grown in hemin-supplemented broth at 30°C. The bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 15 min, washed once with TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA), and resuspended in 1 to 3 ml of TE buffer, depending on the size of the cell pellet. The suspensions were stored at −20°C until they were processed further.

DNA extraction.

The chromosomal DNA of the mycobacteria was isolated as described previously (16). In brief, the mycobacterial cells were lysed with Nagarse protease (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and lysozyme (Sigma). The lysis was followed by phenol-chloroform extractions, RNase (Sigma) digestion, and ethanol precipitation. The DNA concentrations were quantified both with the GeneQuant DNA/RNA calculator (Pharmacia LKB Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom) and by agarose gel electrophoresis by comparison of a sample band to the bands of HindIII-digested bacteriophage lambda DNA (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.). The DNA stock was stored at 4°C, and the diluted DNA was stored at −20°C.

RAPD-PCR.

Random amplified polymorphic DNA PCR analysis (RAPD-PCR) of M. malmoense has been described in detail in a publication describing our previous study in which 45 strains were amplified with selected 10-mer primers (15). In the RAPD-PCR, the genomic DNA is amplified under optimized conditions by using a short, nonspecific oligonucleotide primer. In the present study, other Mycobacterium species were fingerprinted by the same method with the OPA2 primer (Operon Technologies, Inc., Alameda, Calif.).

Fragment extraction from agarose gel.

A DNA product representing a 1,046-bp band that was present in all 45 M. malmoense strains was cut as a slice from the fingerprint of M. malmoense ATCC 29571 obtained in an agarose gel after electrophoresis. The DNA fragment was purified by a phenol extraction method described elsewhere in detail (27).

Cloning and sequencing.

The fragment (named MA2/6) was cloned into SmaI-digested pBluescript II SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) by the standard method (27). The insert was digested with restriction endonucleases SalI and PvuII, and the 557-bp SalI-PvuII fragment was recloned into SalI- and PvuII-digested pBluescript II SK. The cloned inserts were sequenced with an ALF automatic DNA sequencer with the Auto Read Sequencing kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Sollentuna, Sweden) with the primers for the T3 and T7 sequences of pBluescript II SK. The sequence segments were aligned to constitute the complete sequence. Analyses of the DNA sequences were performed with the GeneJockey II computer program (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Dot blot hybridization.

Dot blot hybridizations of mycobacterial chromosomal DNA were carried out by modifying the published protocol (2). One microgram of EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA was applied onto each dot on an Immobilon-N membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) which had been prewetted for 2 s in ethanol and saturated in 3× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). The DNA was denaturated by incubating the membrane for 10 min on two stacked blotting papers (Schleicher & Schuell GmbH, Dassel, Germany) saturated in an alkaline solution (0.5 M NaOH, 1 M NaCl). The neutralization was performed in the same way by using a neutralization solution (1 M Tris-HCl, 2 M NaCl [pH 7.5]). For DNA binding, the dried membrane was baked for 1 h at 80°C according to the instructions of the membrane manufacturer.

The MA2/6 fragment and the 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) probe (16) were chosen as probes for the dot blot hybridization analyses. The probes were 32P labelled with the Rediprime kit (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) with Redivue [α-32P]dCTP AA 0005 (Amersham) according to the instructions on the insert in the Rediprime package. The specific activities of the probes were 4 × 108 cpm/μg for the MA2/6 fragment and 2 × 108 cpm/μg for the 16S rDNA probe.

The membrane was incubated in the prehybridization solution at 65°C for 1 h before hybridization. There was 150 kcpm of labelled probe per ml of hybridization solution, and the hybridization was allowed to proceed for 18 h at 65°C. To visualize the label, the membrane was exposed to Hyperfilm MP (Amersham). If the membrane was to be reprobed, the attached probe was stripped off by incubating the membrane in 0.1 M NaOH for 30 min and in 0.1× SSC–0.2 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 45 min at room temperature.

PCRs.

To prevent carryover contamination, treatment of the strains, extraction of DNA, preparation of PCR mixtures, amplification, and analysis of the amplicons were each done in separate areas. Filter-barrier pipette tips were used at all stages. In the amplification control reactions with 16S rRNA gene primers and nested amplifications with the MA2/6 primers, the PCR mixtures (total volume, 50 μl) contained 1× DynaZyme DNA polymerase reaction buffer (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland), 0.3 μM primers (synthesized by Medprobe, Oslo, Norway), 200 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP (Promega, Madison, Wis.), 1 to 2 ng of genomic DNA (or 1 μl from the product of the first reaction to the second reaction of the nested PCR), and 2 U of DynaZyme DNA polymerase (Finnzymes Oy).

The primers for the amplification control reactions were 16S-A (5′-GGATGACGGCCTTCGGGTTG-3′), which complements bases 366 to 385, and 16S-B (5′-GACAGCCATGCACCACCTGC-3′), which consists of bases 993 to 1012 in the M. malmoense 16S rRNA gene sequence (GenBank accession no. X52930) (25). The primers for the first reaction of the M. malmoense-specific nested PCR were MAL-1A (5′-CGACGAGACACCCCCAGC-3′), which complements bases 12 to 29, and MAL-1B (5′-TCAGCCAGCGGTGTAGC-3′), which consists of bases 988 to 1004; and the primers of the second reaction were MAL-2A (5′-CAGTCAGCGAGGAAGTCGGGAATC-3′), which complements bases 72 to 95, and 5′-end biotinylated primer MAL-2B-biot (5′-GGGTTCATCATTCCGCTGGGCTAC-3′), which consists of bases 482 to 505 in the M. malmoense MA2/6 sequence (GenBank accession no. AF085175).

The amplification programs were optimized for a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 apparatus (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). Control PCRs with 16S rRNA gene primers were performed by a program which included predenaturation at 98°C for 3 min, a first 15 cycles consisting of 96°C for 20 s, 54°C for 35 s, and 72°C for 50 s, and a subsequent 25 cycles consisting of 95°C for 25 s, 58°C for 35 s, and 72°C for 45 s; after these cycles, there was an extra extension step at 72°C for 10 min. In the M. malmoense-specific nested PCR, the first program included predenaturation at 98°C for 3 min and 25 cycles consisting of 96°C for 25 s, 63°C for 50 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and the second one included 25 cycles consisting of 96°C for 20 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 40 s and, finally, an extra extension step at 72°C for 10 min. After the program was run, the reaction tubes were held at 4°C until agarose gel electrophoresis was run.

Agarose gel electrophoresis.

The PCR products were run on a 1.3% agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) gel containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide (Sigma) per ml and 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. The gel was photographed under UV light.

Hybridization of nested PCR product.

The nested PCR products were hybridized with 5′-end digoxigenin-labelled oligonucleotide probe MAL-p-dig (5′-AGCTGTTCGTGGGTATCAGAGAGTTA-3′), which complements bases 160 to 185 (synthesized by Medprobe, Oslo, Norway) in the M. malmoense MA2/6 sequence, in microplate wells by a method described elsewhere (1), with slight modifications. After the amplification reaction with the M. malmoense-specific primers MAL-2A and MAL-2B-biot, 15 μl of the PCR product was applied to the well of a streptavidin-coated microplate (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) in 185 μl of working solution consisting of 1 M phosphate-buffered saline, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1% Tween 20 (pH 7.4). The biotinylated amplification product was immobilized onto the well for 18 h at 4°C. For denaturation of the PCR product, the well was first washed once with 200 μl of 0.1 N NaOH, and after that, 200 μl of 0.1 N NaOH was added and the plate was incubated for 5 min at room temperature. After two washing steps with the working solution, the hybridization with the digoxigenin-labelled oligonucleotide probe MAL-p-dig was carried out in 150 μl of hybridization solution consisting of 6× SSC, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 mM EDTA, 10× Denhardt solution (which contains 0.2% Ficoll 400, 0.2% polyvinylpyrrolidone, and 0.2% bovine serum albumin) for 4 h at 56°C. After hybridization, the well was washed twice with working solution.

The hybridized digoxigenin-labelled oligonucleotide probe was detected by adding to each well 150 μl of anti-digoxin monoclonal antibody clone DI-22 conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) at a dilution of 1:1,000 in working solution. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the well was washed two times. To detect the attached anti-digoxin antibody, 150 μl of substrate solution, prepared from Sigma Fast-pNPP substrate tablets (Sigma), was added. The substrate was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 40 μl of 3 N NaOH per well. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm with a Multiskan plus photometric reader (Labsystems).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been submitted to the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AF085175.

RESULTS

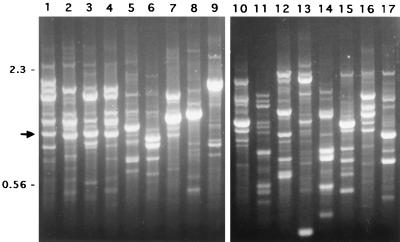

The 45 M. malmoense strains exhibited a variety of RAPD-PCR patterns when the strains were analyzed with the OPA2 10-mer primer. However, one band of 1,046 bp was conserved and was present in the fingerprint of every M. malmoense strain. The band of similar size was uncommon in the other mycobacterial species tested. An example of the fingerprint profiles is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

RAPD fingerprint patterns of the Mycobacterium species obtained with primer OPA2. Lanes 1 to 4, M. malmoense; lane 5, M. gastri; lane 6, M. scrofulaceum; lane 7, M. asiaticum; lane 8, M. avium; lane 9, M. intracellulare; lane 10, M. xenopi; lane 11, M. szulgai; lane 12, M. kansasii; lane 13, M. haemophilum; lane 14, M. marinum; lane 15, M. tuberculosis; lane 16, M. celatum I; lane 17, M. celatum II. The 1,046-bp fragment of M. malmoense is indicated by an arrow. On the basis of RAPD, this fragment was analyzed further as a candidate for a species-specific probe for M. malmoense. Numbers on the left are in kilobase pairs.

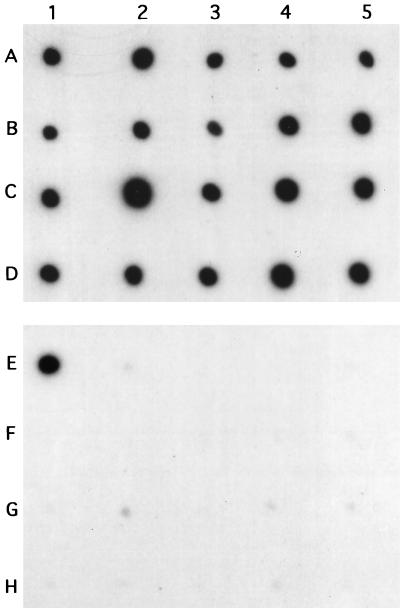

The existence of the MA2/6 sequence in the genomes of mycobacteria other than M. malmoense was estimated by dot blot hybridization analysis of the set of the mycobacterial strains selected. Only M. malmoense DNA exhibited a distinct positive result (Fig. 2). On the same membranes, all strains studied produced a positive result by the control dot blot hybridization assay, carried out with the labelled 16S rDNA fragment. On this basis, the MA2/6 fragment was regarded as a potential candidate for an M. malmoense-specific fragment. No high degrees of nucleotide sequence homologies were found in homology searches when the nucleotide sequence of MA2/6 was compared with those present in GenBank version 110.0.

FIG. 2.

Dot blot analysis of EcoRI-digested mycobacterial DNA with the 32P-labelled 16S rDNA probe (rows A to D) and the MA2/6 fragment (rows E to H). A1 and E1, M. malmoense ATCC 29571; A2 and E2, M. tuberculosis ATCC 25177; A3 and E3, M. tuberculosis ATCC 27294 (H37Rv); A4 and E4, M. avium ATCC 15769; A5 and E5, M. intracellulare ATCC 13950; B1 and F1, M. bovis BCG vaccine strain; B2 and F2, M. bovis BCG clinical isolate; B3 and F3, M. kansasii ATCC 12478; B4 and F4, M. fortuitum ATCC 6841; B5 and F5, M. fortuitum ATCC 6842; C1 and G1, M. marinum ATCC 927; C2 and G2, M. asiaticum ATCC 25276; C3 and G3, M. xenopi ATCC 19250; C4 and G4, M. nonchromogenicum ATCC 19530; C5 and G5, M. nonchromogenicum ATCC 35783; D1 and H1, M. simiae ATCC 25275; D2 and H2, M. phlei ATCC 12298; D3 and H3, M. flavescens ATCC 14474; D4 and H4, M. smegmatis ATCC 35797; D5 and H5, M. fallax ATCC 35219.

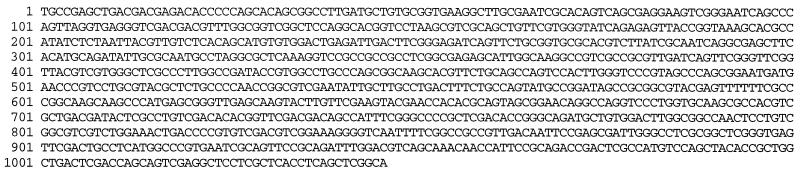

On the basis of the sequencing data for the MA2/6 fragment (Fig. 3), several primers were designed for PCR. The M. malmoense specificity of the primers were evaluated by combining the sense and antisense primers in different combinations. The primers found to be most suitable are described in Materials and Methods. Primers MAL-1A and MAL-1B produced a band of the expected size of 993 bp only from M. malmoense at 60°C or above. In contrast, a band was also obtained from M. tuberculosis, M. kansasii, and M. fortuitum if the annealing temperature was adjusted to below 56°C (data not shown). The band produced from M. tuberculosis and M. kansasii had a size of approximately 1.3 kbp, whereas the band from M. fortuitum was equal in size to the M. malmoense band. The PCR products amplified with primers MAL-1A and MAL-1B from M. tuberculosis, M. kansasii, and M. fortuitum were partially sequenced. No homologies with the M. malmoense sequence were observed (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence of fragment MA2/6 in the genome of M. malmoense ATCC 29571. The sequence has been submitted to the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AF085175.

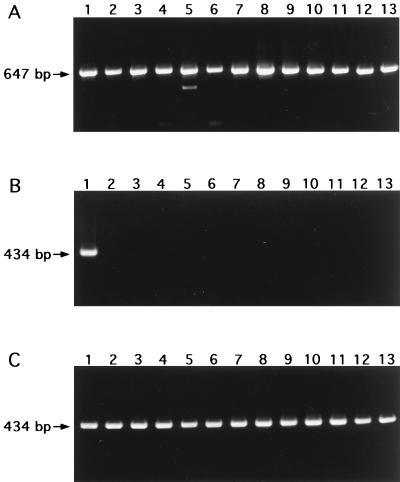

Nested PCR, consisting of reactions first with primers MAL-1A and MAL-1B and second with primers MAL-2A and MAL-2B-biot, was highly specific for M. malmoense. Among the mycobacterial species included in this analysis, only the 48 M. malmoense strains produced a band of 434 bp in the nested PCR. No bands of other sizes were detected in the lanes containing M. malmoense. The lanes containing other Mycobacterium species were free of any bands. A subset of the results is presented in Fig. 4. In hybridization analysis of the nested PCR products with the digoxigenin-labelled oligonucleotide probe MAL-p-dig, all M. malmoense strains with the exception of one clinical isolate gave an absorbance value of 0.85 to 1.13; the absorbance value for the clinical isolate that was the exception was 0.58. In contrast, the absorbance values for the other Mycobacterium species were less than 0.09, indicating negative results. The mean value for the negative control reactions (PCRs without sample DNA) was 0.02.

FIG. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis after PCR with 16S rRNA gene primers 16S-A and 16S-B (A) and nested PCR with M. malmoense-specific primers MAL-1A and MAL-1B, and primers MAL-2A and MAL-2B-biot (B). Lane 1, M. malmoense ATCC 29571; lane 2, M. tuberculosis ATCC 27294 (H37Rv); lane 3, M. tuberculosis ATCC 25177; lane 4, M. bovis BCG vaccine strain; lane 5, M. avium ATCC 15769; lane 6, M. intracellulare ATCC 13950; lane 7, M. scrofulaceum ATCC 19981; lane 8, M. szulgai ATCC 35799; lane 9, M. gastri ATCC 15754; lane 10, M. marinum ATCC 927; lane 11, M. kansasii ATCC 12478; lane 12, M. fortuitum ATCC 6841; lane 13, M. xenopi ATCC 19250. (C) Nested PCR with M. malmoense-specific primers MAL-1A and MAL-1B, and primers MAL-2A and MAL-2B-biot. Lane 1, M. malmoense ATCC 29571; lanes 2, 4, 8, 10, and 11, Finnish clinical isolates of M. malmoense; lanes 3, 5 to 7, and 9, British clinical isolates of M. malmoense; lanes 12 and 13, Finnish environmental isolates of M. malmoense.

Control amplifications carried out with the primers for the 16S rRNA gene confirmed that the bacterial PCR templates also amplified those strains that remained negative with the M. malmoense-specific primers. All Mycobacterium strains produced a band of approximately 647 bp in the control reactions. The sensitivity of the nested PCR was estimated by using a dilution series of M. malmoense chromosomal DNA and the DNA of the plasmid containing the MA2/6 fragment. Both 4 fg of chromosomal DNA and 12 ag of plasmid DNA could be detected, indicating the limit of detection to represent one target molecule in a reaction tube. There was no difference in the detection limit by electrophoresis or hybridization. A slightly visible band by gel electrophoresis gave an absorbance reading of 0.50 by hybridization analysis.

DISCUSSION

The clinical significance of mycobacterial species such as M. malmoense is likely to be underestimated; its detection in clinical samples is particularly difficult due to its exceptionally slow rate of growth and the need for special culture conditions (8, 12, 13). We have previously confirmed that modifications to culture media increase the rates of detection of such species (12). Biochemical identification of M. malmoense is laborious, and some uncommon Mycobacterium species may easily be incorrectly identified as M. malmoense (34). Nucleic acid amplification methods offer an alternative approach to the detection and identification of microbes whose identities are difficult to confirm by conventional methods. Several PCR protocols have been used for the identification of atypical mycobacteria. In most cases, identification has been based on the detection of differences in conserved sequences after amplification with genus-specific primers. This also applies to M. malmoense, at least by selected methods (6, 24, 28). In the present study, we wanted to develop a rapid technique that was also potentially suitable for the direct detection of M. malmoense from clinical or environmental samples. The specific PCR method makes it possible to preliminarily identify M. malmoense DNA within a working day. With the hybridization of the amplicon, the method takes 2 days. All M. malmoense strains tested, including an ATCC strain and 48 clinical or environmental isolates, produced the expected PCR product. Furthermore, the results verified the high degree of species specificity of the MA2/6 fragment. None of the 43 other mycobacterial species tested produced amplicons if the specific PCR conditions were used. We performed the amplification reactions with the 16S rRNA gene primers as DNA or inhibition controls. The sensitivity of the nested PCR used was high under the experimental conditions used.

There are several ways to find species-specific areas in microbial genomic nucleic acids. The specific sites close to or within a conserved part of the genome, such as the 16S rRNA genes, are potential targets that are mostly found by sequencing genomes of several species. It is possible to use primers which anneal to the genomes of many species if further identification is done by analysis of the amplified sequences by restriction endonuclease digestion, oligonucleotide hybridization, or sequencing. All of these applications can reveal a difference of even a single base.

We used an approach in which the RAPD fingerprint profiles of M. malmoense strains and some closely related mycobacterial species were compared. The basis of the present study was the detection in the M. malmoense strains of conserved bands which were not present in the other species. One amplification product of this kind was found to be M. malmoense specific, and it was further analyzed as a suitable candidate for targeting by nested PCR analysis. To ensure the species specificity of fragment MA2/6, it was extracted from an agarose gel and used as a probe in a hybridization analysis in which the template DNA was derived from several M. malmoense strains and other closely related species. The primer candidates were selected from the sequence of the fragment by using the appropriate computer program, and the M. malmoense-specific primers were found experimentally.

Negative hybridization results with the other species tested suggested that the MA2/6 fragment was a potential candidate as an amplification target. The stringency in the dot blot hybridization was relatively high due to the hybridization temperature and the salt concentration used. Therefore, sequences closely related to the MA2/6 probe could have been detected. In addition, the MA2/6 sequence did not show a high degree of nucleotide sequence homology with any of the sequences in data banks. With the selected primers, some PCR products were obtained from mycobacterial species other than M. malmoense, but only at the low annealing temperatures that favor nonspecific binding. The specificity and sensitivity of the PCR were increased by using two nested primer pairs.

By combining the developed nested PCR with a sample processing method such as that of Eisenach et al. (5), it could be used not only for the identification of M. malmoense from cultures but also for the direct detection of M. malmoense from samples without the need for preceding isolation of the organism. This would allow the detection of the organism in both clinical samples and suspected environmental reservoirs. Since the identification is based on the detection of a specific sequence with species-specific primers instead of the detection of minor differences in the sequence flanked by the binding sites of the universal primers, the results can be interpreted quickly and easily. The sensitivity of the amplification reaction was excellent. When the sample collection and preparation are optimized, M. malmoense could be reliably detected in the course of a few days. This requires further evaluation with clinical and environmental specimens.

We conclude that the nested PCR described here is a specific method for the identification of M. malmoense and that the RAPD-PCR is a useful tool in searches for species-specific genomic fragments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eila Pelkonen for technical assistance.

This study was supported by the Memorial Foundation of Maud Kuistila and the Finnish Antituberculosis Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann, L., I. T. Harvima, J. Pelkonen, V. Ritamäki-Salo, A. Naukkarinen, R. J. Harvima, and M. Horsmanheimo. Mast cells of psoriatic skin are strongly positive for interferon-gamma. Br. J. Dermatol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Andersson M L M, Young B D. Quantitative filter hybridisation. In: Hames B D, Higgins S J, editors. Nucleic acid hybridisation: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1985. pp. 73–111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bollert F G, Watt B, Greening A P, Crompton G K. Non-tuberculous pulmonary infections in Scotland: a cluster in Lothian? Thorax. 1995;50:188–190. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Beenhouwer H, Liang Z, De Rijk P, Van Eekeren C, Portaels F. Detection and identification of mycobacteria by DNA amplification and oligonucleotide-specific capture plate hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2994–2998. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2994-2998.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenach K D, Cave M D, Crawford J T. PCR detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glennon M, Cormican M G, Ni Riain U, Heginbothom M, Gannon F, Smith T. A Mycobacterium malmoense-specific DNA probe from the 16S/23S rRNA intergenic spacer region. Mol Cell Probes. 1996;10:337–345. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriques B, Hoffner S E, Petrini B, Juhlin I, Wahlen P, Kallenius G. Infection with Mycobacterium malmoense in Sweden: report of 221 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:596–600. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.4.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffner S E, Henriques B, Petrini B, Kallenius G. Mycobacterium malmoense: an easily missed pathogen. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2673–2674. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2673-2674.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horsburgh C R., Jr Epidemiology of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Semin Respir Infect. 1996;11:244–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katila M L, Brander E, Jantzen E, Huttunen R, Linkosalo L. Chemotypes of Mycobacterium malmoense based on glycolipid profiles. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:355–358. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.355-358.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katila M L, Iivanainen E, Torkko P, Kauppinen J, Martikainen P, Väänänen P. Isolation of potentially pathogenic mycobacteria in the Finnish environment. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1995;98:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katila M L, Mattila J. Enhanced isolation of MOTT on egg media of low pH. APMIS. 1991;99:803–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1991.tb01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katila M L, Mattila J, Brander E. Enhancement of growth of Mycobacterium malmoense by acidic pH and pyruvate. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:998–1000. doi: 10.1007/BF01967574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katila M L, Viljanen T, Brander E. Mycobacterium malmoense infections. Z Erkr Atmungsorgane. 1991;176:159–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kauppinen J, Mäntyjärvi R, Katila M L. Random amplified polymorphic DNA genotyping of Mycobacterium malmoense. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1827–1829. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1827-1829.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kauppinen J, Pelkonen J, Katila M L. RFLP analysis of Mycobacterium malmoense strains using ribosomal RNA gene probes: an additional tool to examine intraspecies variation. J Microbiol Methods. 1994;19:261–267. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirschner P, Springer B, Vogel U, Meier A, Wrede A, Kiekenbeck M, Bange F C, Bottger E C. Genotypic identification of mycobacteria by nucleic acid sequence determination: report of a 2-year experience in a clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2882–2889. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2882-2889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kox L F, Jansen H M, Kuijper S, Kolk A H. Multiplex PCR assay for immediate identification of the infecting species in patients with mycobacterial disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1492–1498. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1492-1498.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kox L F, van Leeuwen J, Knijper S, Jansen H M, Kolk A H. PCR assay based on DNA coding for 16S rRNA for detection and identification of mycobacteria in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3225–3233. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3225-3233.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamden K, Watson J M, Knerer G, Ryan M J, Jenkins P A. Opportunist mycobacteria in England and Wales: 1982 to 1994. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev. 1996;6:R147–R151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luquin M, Ausina V, Lopez Calahorra F, Belda F, Garcia Barcelo M, Celma C, Prats G. Evaluation of practical chromatographic procedures for identification of clinical isolates of mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:120–130. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.120-130.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez Murcia A J, Rodriguez Valera F. The use of arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) to develop taxa specific DNA probes of known sequence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;124:265–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Portaels F, Larsson L, Jenkins P A. Isolation of Mycobacterium malmoense from the environment in Zaire. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1995;76:160–162. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogall T, Flohr T, Böttger E C. Differentiation of Mycobacterium species by direct sequencing of amplified DNA. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1915–1920. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-9-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogall T, Wolters J, Flohr T, Böttger E C. Towards a phylogeny and definition of species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:323–330. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-4-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito H, Tomioka H, Sato K, Tasaka H, Dekio S. Mycobacterium malmoense isolated from soil. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:313–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soini H, Bottger E C, Viljanen M K. Identification of mycobacteria by PCR-based sequence determination of the 32-kilodalton protein gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2944–2947. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2944-2947.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takewaki S, Okuzumi K, Manabe I, Tanimura M, Miyamura K, Nakahara K, Yazaki Y, Ohkubo A, Nagai R. Nucleotide sequence comparison of the mycobacterial dnaJ gene and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for identification of mycobacterial species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:159–166. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor T B, Patterson C, Hale Y, Safranek W W. Routine use of PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for identification of mycobacteria growing in liquid media. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:79–85. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.79-85.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torkko P, Suutari M, Suomalainen S, Paulin L, Larsson L, Katila M L. Separation among species of Mycobacterium terrae complex by lipid analyses: comparison with biochemical tests and 16S rRNA sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:499–505. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.499-505.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tortoli E, Piersimoni C, Bartoloni A, Burrini C, Callegaro A P, Caroli G, Colombrita D, Goglio A, Mantella A, Tosi C P, Simonetti M T. Mycobacterium malmoense in Italy: the modern Norman invasion? Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:341–346. doi: 10.1023/a:1007375114106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valero-Guillén P, Martín-Luengo F, Larsson L, Jimenez J, Juhlin I, Portaels F. Fatty and mycolic acids of Mycobacterium malmoense. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:153–154. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.1.153-154.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wayne L G, Sramek H A. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1–25. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zolg J W, Philippi Schulz S. The superoxide dismutase gene, a target for detection and identification of mycobacteria by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2801–2812. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2801-2812.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]