Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, mental health among youth has been negatively affected. Youth with a history of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), as well as youth from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds, may be especially vulnerable to experiencing COVID-19–related distress. The aims of this study are to examine whether exposure to pre-pandemic ACEs predicts mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in youth and whether racial-ethnic background moderates these effects.

Methods

From May to August 2020, 7983 youths (mean age, 12.5 years; range, 10.6–14.6 years) in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study completed at least one of three online surveys measuring the impact of the pandemic on their mental health. Data were evaluated in relation to youths' pre-pandemic mental health and ACEs.

Results

Pre-pandemic ACE history significantly predicted poorer mental health across all outcomes and greater COVID-19–related stress and impact of fears on well-being. Youths reported improved mental health during the pandemic (from May to August 2020). While reporting similar levels of mental health, youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds had elevated COVID-19–related worry, stress, and impact on well-being. Race and ethnicity generally did not moderate ACE effects. Older youths, girls, and those with greater pre-pandemic internalizing symptoms also reported greater mental health symptoms.

Conclusions

Youths who experienced greater childhood adversity reported greater negative affect and COVID-19–related distress during the pandemic. Although they reported generally better mood, Asian American, Black, and multiracial youths reported greater COVID-19–related distress and experienced COVID-19–related discrimination compared with non-Hispanic White youths, highlighting potential health disparities.

Keywords: Adolescence, Adverse childhood experiences, COVID-19, Health disparities, Mental health, Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic may have created an international secondary mental health crisis, with significant increases in mental health problems being reported (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Preadolescents and adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to changes in mental well-being during the pandemic due to the combined stress of adolescent development (10), transitions to virtual learning (11), routine disruptions (12), reduced interaction with peers (13), and additional family stressors (14). Since the onset of the pandemic, several studies have shown increases in mental health symptoms in children and adolescents in China (2, 3, 4), Western Europe (1,15), Canada (16), and the United States (5,7). Given this emerging mental health crisis, identifying particularly vulnerable youth is important for targeted interventions.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) may be a central risk factor for COVID-19–related mental health problems. ACEs include traumatic experiences such as physical abuse, neglect, and family history of psychiatric and substance use disorders (17,18), with more recent research including other traumatic events such as community violence (19,20) and racial discrimination (20, 21, 22, 23). ACEs have been linked with negative physical health outcomes (24,25) and alterations in biological stress response (26,27) and neural development (28,29). Experiencing childhood adversity has also been associated with poorer mental health during adolescence through adulthood (18,30,31). These findings support the diathesis-stress and stress-sensitization models that posit that exposure to chronic early-life stress, such as ACEs, can lead to dysregulation in biological responses to stress, reducing one’s tolerance for future stressful events and increasing one’s risk for dysregulated affect and downstream poorer mental health (32,33).

Aligning with these models, children who have experienced ACEs may be more susceptible to mental health challenges during large-scale stressful circumstances, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, studies have shown links between ACEs and greater anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and depressive symptoms during the pandemic in Chinese adolescents (34) and college students (35), German adults (36), and U.S. adolescents (37) and college students (38). However, studies investigating ACEs and mental health have been limited in sample size (36,37) and primarily conducted outside of the United States, and only two studies to date assessed ACEs pre-pandemic (36,37) while others (34,35,38) were cross-sectional.

Notably, children from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds disproportionately experience more ACEs (39, 40, 41). In the United States, 45% of children (61% of Black and 50% of Latinx children) report at least one ACE, and Black children have nearly twice the odds of having more than two ACEs compared with non-Hispanic White children (39). Differences in ACEs across racial-ethnic groups may reflect how forms of childhood adversity relate to systemic social inequalities across community environments (e.g., community violence, disparities in incarceration rates) and access to resources (e.g., extreme financial hardship, access to health care), which differentially affect people of color (41). Within the United States, COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality rates have been significantly higher in historically marginalized communities, with Black, Indigenous, and Latinx adults being two times more likely to die of COVID-19 than White adults (42, 43, 44, 45). Furthermore, during the pandemic, adults from Black, Latinx, and multiracial backgrounds have reported greater impacts on their mental health than non-Hispanic White adults (46,47). Public health models propose that this differential impact of COVID-19 across communities represents a syndemic, where the global health pandemic is co-occurring and intersecting with structural racism and mental health inequities, leading to poorer outcomes (48, 49, 50, 51). However, few studies have examined the impact of ACEs on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in preadolescents and adolescents from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds in the United States.

To expand on this literature, this study examined whether ACEs measured before the COVID-19 pandemic predict mental health outcomes during the pandemic in youths enrolled in the nationwide, longitudinal Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study and whether youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds demonstrate a stronger relationship between ACEs and mental health outcomes across multiple time points in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on prior literature, we hypothesize that those who have experienced ACEs will be more likely to experience increased symptoms of negative affect, reduced positive affect, and poorer mental health in general and COVID-19–related outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods and Materials

Participants and Design Overview

Participants in this study were drawn from the larger ABCD Study cohort of 11,880 children (recruited in 2016–2018 at ages 9 or 10 years from 22 sites throughout the United States) (52,53). School-based recruitment was used to match the demographic profile of the American Community Survey enrollment statistics within catchment regions (54). All study procedures were approved by the centralized University of California San Diego Institutional Review Board. Each youth and parent in the ABCD Study were sent links to optional surveys about the impact of the pandemic via e-mail and text in May (survey 1), June (survey 2), and August (survey 3) of 2020. Both youths and parents were compensated $5 per completed survey. Participants in these analyses completed the ABCD Study baseline and 1-year follow-up assessments and at least one mental health outcome in the COVID-19 impact survey, which included 7983 unique participants (survey 1: n = 5620 youths; survey 2: n = 5903 youths; survey 3: n = 5411 youths).

Measures

Only selected measures included in these analyses are described here. This study used baseline and 1-year follow-up data from demographic, physical health, mental health (55), substance use (56), and family, culture, and environment (57) modules.

Demographic Variables and Additional Covariates

Demographic variables for sex assigned at birth, race, ethnicity, parental educational attainment, and household income were all reported by parents pre-pandemic at the study baseline (55), and visit and age were measured at the first COVID-19 impact survey. Additional COVID-19–related stressors that may also relate to youth mental health and affect, such as family job/wage loss and changes in school environment (e.g., virtual learning), were also reported by parents at each COVID-19 impact survey.

Coding of ACEs From Pre-COVID/Baseline Data

ACEs were coded based on measures collected at the ABCD Study baseline and 1-year follow-up assessments (55, 56, 57, 58, 59). Cumulative coded ACE risk scores were created by summing across parent- and youth-identified experiences, with endorsement of ever experiencing an event from an ACE category (e.g., emotional abuse, physical neglect) counting as 1 point (60) (Information related to specific measures and ACE scoring algorithm can be found in the Supplement). ACE categories included in coded scoring were as follows: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; household substance use; mental illness in household; parental separation/divorce; family member involvement with legal system; emotional and physical neglect; extreme financial adversity; racial discrimination; bullying; domestic violence; grief; community violence; natural disaster; witnessing death or destruction in a war zone; witnessing or being present during an act of terrorism; car accident; or other significant accident requiring medical attention (see Table S1 for proportions for each ACE category). The cumulative coded ACE score ranged from 0 to 21.

Baseline Internalizing Symptoms

Baseline age-corrected t scores from the internalizing problems scale on the Child Behavior Checklist-Parent form (55,61) were used, which includes parental report of child psychopathology (i.e., anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic complaints syndrome scores) in the last 6 months.

ABCD COVID-19 Impact Survey Measures

NIH Toolbox Emotion Battery v2.0: The Sadness Scale (assessed at survey 1 and survey 3) and Fear Scale (assessed at survey 2) are 8-item scales assessing youth report of low mood and cognitive elements of depression and anxiety related to threat, respectively. Responses on both scales ranged from 1 = “never” to 5 = “almost always.” The Positive Affect Scale (assessed at survey 2) is a 9-item scale measuring youth report of emotions such as happiness, excitement, and joy, and responses ranged from 1 = “not true” to 3 = “very true.” Scores across all measures were converted to normalized t scores for analyses. One question was also created to assess youths’ experiences of anger and frustration in the past week (assessed at survey 1 and survey 3).

Perceived Stress Scale-4: The Perceived Stress Scale-4 (assessed at survey 1 to survey 3) (62) is a brief measure designed to assess broad psychological stress in the past month, and responses ranged from 0 = “never” to 4 = “very often.”

Coronavirus Health Impact Survey V.0.2 Short Form-Worry and Uncertainty Stress: Two questions were chosen to assess youth report of COVID-19–related worry (assessed at survey 1 to survey 3) and stress associated with COVID-19 uncertainty (assessed at survey 2). Both item responses ranged from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “extremely.”

Fear of Illness and Virus Evaluation Scale: Impact of Illness and Virus Fears. Questions were included to assess youths’ appraisal of the impact the virus has had on their emotional well-being and life enjoyment (assessed at survey 1 and survey 3) (63), and responses ranged from 1 = “not true” to 4 = “definitely true.”

Experienced Racial Discrimination Related to COVID-19: Youths were asked whether they had directly experienced racial discrimination related to COVID-19 (assessed at survey 1 to survey 3), and responses ranged from 0 = “never” to 4 = “very frequently.”

Statistical Analyses

This study used data from the ABCD 3.0 data release (https://doi.org/10.15154/1519007) and the ABCD COVID-19 Survey first data release (https://doi.org/10.15154/1520584). All analyses were run in R version 4.0.3 (64). Models for each mental health outcome were estimated using a linear mixed-effects design using the lme4 package (65). Primary predictors in each model included ACEs, race, ethnicity, and a measure of time (i.e., survey time points), and ACE × time. Covariates included age, sex assigned at birth, parental educational attainment, household income, baseline Child Behavior Checklist internalizing symptoms, and COVID-19 stressors (i.e., family job/wage loss and school environment). Furthermore, to test the secondary aims, linear mixed-effects models with the additions of ACE × race (or ethnicity) or ACE × race (or ethnicity) × time analyses were conducted. All models accounted for the independent second-level random effects of sibling/twin status, ABCD Study collection site, and subject (i.e., repeated-measure analyses). Benjamini-Hochberg corrections were used to adjust significance levels for general mental health and COVID-19–specific outcomes separately to reduce false discovery rate at .05 level (66); these corrections provided a threshold of 0.019 for general mental health outcomes and 0.049 for COVID-19–specific outcomes.

To better understand observed racial/ethnic differences in COVID-19–related mental health outcomes, post hoc linear mixed-effects analyses were conducted to examine whether race or ethnicity was associated with experiencing COVID-19 discrimination after controlling for aforementioned demographic, covariates, and random effects. Furthermore, we added the experienced COVID-19 racial discrimination variable to models with a significant ACE × race (or ethnicity) interaction for COVID-19–specific outcomes (i.e., COVID-19 worry) (see the Supplement).

Results

Demographic Analysis

See Table 1 for details on demographics for the full ABCD cohort and this sample (n = 7983). Compared to the full ABCD cohort, this sample was more likely to have higher parental education and household income, identify race as White, and identify as non-Hispanic. Average participant age at survey 1 was 12.5 years. In this sample, average ACE scores were lower (mean = 2.45, SD = 1.96) than scores in the full ABCD cohort (mean = 3.09, SD = 2.18).

Table 1.

Demographics for the ABCD Study and Study Sample

| Demographics | Release 3.0, %, Baseline Data, N = 11,880 | Study Sample, %, n = 7983 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, Female | 48 | 49 |

| Race (Youth-Identified) | ||

| Asian American | 2 | 3 |

| Black | 16 | 11 |

| White | 63 | 69 |

| Other racial/multiracial identity | 17 | 16 |

| Missing/undefined | 1 | 1 |

| Ethnicity (Youth-Identified) | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 20 | 18 |

| Missing/undefined | 1 | 1 |

| Parental Education | ||

| Less than HS diploma | 5 | 2 |

| HS diploma/GED | 10 | 7 |

| Some college | 26 | 22 |

| Bachelor | 25 | 28 |

| Postgraduate | 34 | 40 |

| Household Income | ||

| <$50,000 | 27 | 21 |

| ≥$50,000 to <$100,000 | 26 | 28 |

| ≥$100,000 | 38 | 44 |

| Missing/undefined | 9 | 7 |

ABCD, Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development; GED, General Educational Development; HS, high school.

ACE scores significantly differed by age at first COVID-19 survey (F1,6503 = 10.06, p = .0015) (ACE scores decreased as age increased), sex assigned at birth (F1,7994 = 4.81, p = .028) (males reported more ACEs), race (F3,7904 = 120, p < .001) (Black youths reported the highest ACE scores, followed by Other/multiracial, White, and Asian American), ethnicity (F1,7900 = 10.24, p = .001) (Latinx youths reported more ACEs), baseline household income (F2,7448 = 554.4, p < .001) (youths with lower household income had higher ACEs), baseline parental educational attainment (F4,7982 = 203.8, p < .001) (youths with parents with a high-school diploma or some college had higher ACEs than other groups), and baseline internalizing scores (F1,7994 = 833.2, p < .001) (experiencing more ACEs was related to higher baseline internalizing scores).

Primary Findings: General Mental Health

Sadness Scale

-

•

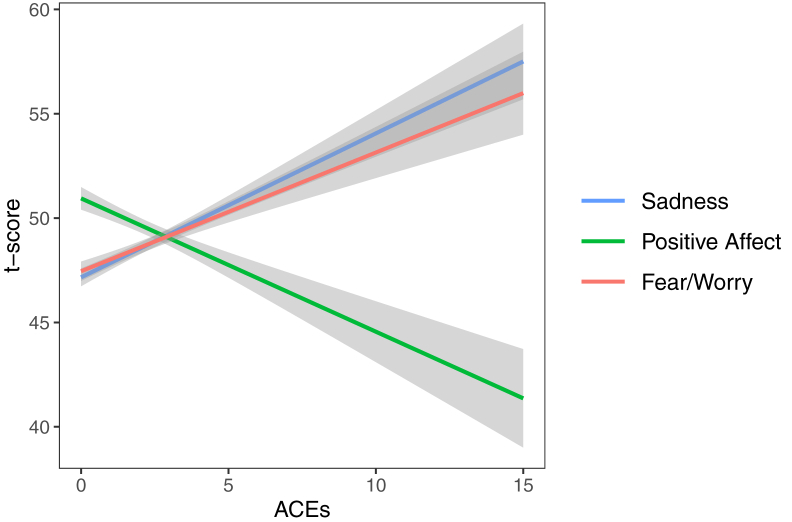

ACEs: Greater number of ACEs significantly predicted greater sadness (Table 2 and Figure 1).

-

•

Time: Sadness significantly decreased across the three surveys with no ACE × time interaction.

-

•

Race/ethnicity: Race was significantly related to sadness. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, Black youths reported less sadness.

-

•

ACE × race or ethnicity × time: No effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Older youths, girls, and those with greater internalizing scores (p values < .001) reported greater sadness.

Table 2.

Predictors of Adolescent General Mental Health Outcomes During COVID-19 Pandemic

| Outcome | Survey Time Point | Factors/Covariates | Estimate | SE | df | t | Uncorrected p Value | FDR p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sadness | Surveys 1 and 3 | ACEs | 0.59 | 0.14 | 7032.30 | 3.92 | <.001a | <.001 |

| Time | −1.56 | 0.25 | 4062.51 | −6.36 | <.001 | |||

| ACE × time | 0.07 | 0.08 | 3999.14 | 0.87 | .38 | .72 | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.26 | 0.85 | 4145.30 | −0.30 | .76 | |||

| Black | −1.63 | 0.54 | 4471.59 | −3.00 | .0027 | |||

| Other/multiracial | 0.37 | 0.40 | 4502.79 | 0.93 | .35 | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.38 | 1.17 | 6326.79 | 0.33 | .74 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 1.60 | 1.053 | 6519 | 1.51 | .13 | .37 | ||

| Black | 0.77 | 0.48 | 6558 | 1.61 | .11 | .36 | ||

| Other/multiracial | 0.038 | 0.34 | 6498 | 0.11 | .91 | .98 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | 0.055 | 0.37 | 6523.60 | 0.15 | .88 | .98 | ||

| ACE × race × time | ||||||||

| Asian | −0.80 | 0.60 | 3519 | −1.346 | .18 | .48 | ||

| Black | −0.74 | 0.29 | 4368 | −2.57 | .01 | .07 | ||

| Other/multiracial | −0.0027 | 0.20 | 3881 | −0.013 | .99 | .99 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity × time | −0.057 | 0.22 | 4118.42 | −0.257 | .79 | .97 | ||

| Positive Affect | Survey 2 | ACEs | −0.46 | 0.11 | 3321.04 | −4.24 | <.001a | <.001 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.59 | 1.06 | 3075.60 | −0.56 | .58 | |||

| Black | 1.95 | 0.76 | 3074.96 | 2.56 | .01 | |||

| Other/multiracial | −0.02 | 0.53 | 3120.15 | −0.038 | .97 | |||

| Ethnicity | −1.12 | 0.87 | 2779.34 | −1.26 | .21 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian | 0.42 | 0.69 | 3392.51 | 0.61 | .54 | .75 | ||

| Black | 0.60 | 0.35 | 3410.42 | 1.72 | .086 | .36 | ||

| Other/multiracial | 0.41 | 0.25 | 3340.69 | 1.68 | .094 | .36 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | 0.34 | 0.26 | 3347.84 | 1.30 | .19 | .48 | ||

| Fear/Worry | Survey 2 | ACEs | 0.46 | 0.092 | 3792.71 | 4.98 | <.001a | <.001 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.12 | 0.91 | 2837.32 | 0.13 | .89 | |||

| Black | −0.16 | 0.61 | 2846.98 | −0.25 | .80 | |||

| Other/multiracial | 0.95 | 0.45 | 3175.43 | 2.13 | .034 | |||

| Ethnicity | −0.31 | 0.74 | 2361.73 | −0.42 | .67 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.47 | 0.61 | 3886 | 0.77 | .44 | .74 | ||

| Black | 0.12 | 0.28 | 3891 | 0.42 | .67 | .84 | ||

| Other/multiracial | −0.14 | 0.21 | 3774 | −0.67 | .50 | .74 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | 0.16 | 0.22 | 3783.14 | 0.72 | .47 | .74 | ||

| Anger/Frustration | Surveys 1 and 3 | ACEs | 0.046 | 0.015 | 6466 | 3.03 | .0024b | .02 |

| Time | −0.15 | 0.028 | 4390 | −5.440 | <.001 | |||

| ACE × time | 0.0051 | 0.0091 | 4309 | 0.56 | .57 | .76 | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.083 | 0.079 | 3965 | −1.05 | .29 | |||

| Black | −0.11 | 0.051 | 4412 | −2.10 | .036 | |||

| Other/multiracial | −0.0063 | 0.037 | 4358 | −0.17 | .87 | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.21 | 0.13 | 6031 | 1.63 | .10 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.085 | 0.11 | 5732 | −0.74 | .46 | .74 | ||

| Black | 0.0090 | 0.052 | 6303 | 0.17 | .86 | .98 | ||

| Other/multiracial | −0.057 | 0.038 | 5958 | −1.52 | .13 | .37 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | −0.027 | 0.040 | 6104 | −0.68 | .50 | .74 | ||

| ACE × race × time | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.00627 | 0.069 | 3672 | 0.091 | .93 | .98 | ||

| Black | −0.021 | 0.033 | 4792 | −0.64 | .52 | .72 | ||

| Other/multiracial | 0.024 | 0.023 | 4161 | 1.03 | .30 | .61 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity × time | 0.027 | 0.025 | 4480 | 1.07 | .30 | .60 | ||

| Perceived Stress | Surveys 1–3 | ACEs | 0.19 | 0.029 | 12,030 | 6.38 | <.001a | <.001 |

| Time | −0.28 | 0.034 | 8190 | −8.14 | <.001 | |||

| ACE × time | 0.00016 | 0.011 | 8201 | 0.014 | .98 | .99 | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.30 | 0.21 | 4371 | 1.47 | .14 | |||

| Black | 0.14 | 0.13 | 4682 | 1.05 | .29 | |||

| Other/multiracial | 0.16 | 0.098 | 4658 | 1.68 | .094 | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.39 | 0.24 | 9926 | 1.63 | .10 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.10 | 0.22 | 12,470 | 0.47 | .64 | .82 | ||

| Black | 0.11 | 0.097 | 12,230 | 1.14 | .26 | .58 | ||

| Other/multiracial | −0.01 | 0.071 | 12,270 | −0.15 | .88 | .98 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | −0.15 | 0.076 | 12,160 | −1.96 | .05 | .29 | ||

| ACE × race × time | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.063 | 0.085 | 7421 | −0.74 | .46 | .74 | ||

| Black | −0.075 | 0.041 | 8757 | −1.84 | .066 | .33 | ||

| Other/multiracial | −0.032 | 0.028 | 7993 | −1.12 | .26 | .58 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity × time | 0.050 | 0.031 | 8282 | 161 | .11 | .36 |

ACE, adverse childhood experience; FDR, false discovery rate.

p < .001; p value remained significant after corrections.

p < .05; p value remained significant after corrections.

Figure 1.

Greater adverse childhood experience (ACE) scores relate to poorer mood during the COVID-19 pandemic. Graph shows bivariate relationship between ACE scores and sadness, positive affect, and fear/worry outcomes (shaded portions represent standard error). The presented data for sadness represents the mean sadness scores across time (assessed at surveys 1 and 3), while fear/worry and positive affect represent mean scores at survey 2. As ACE scores increase, sadness and fear increase and positive affect decreases.

Positive Affect Scale

-

•

ACEs: Higher ACE scores significantly predicted less positive affect.

-

•

Race/ethnicity: Race was significantly related to positive affect. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, Black youths reported more positive affect.

-

•

ACE × race or ethnicity: No effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Older youths (p = .017), girls (p = .001), and those with greater internalizing scores (p < .001) reported less positive mood.

Fear/Worry Scale

-

•

ACEs: Greater number of ACEs significantly predicted more fear and worry.

-

•

Race/ethnicity: Race was significantly related to fear/worry. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, youths from other racial or multiracial backgrounds reported greater fear/worry.

-

•

ACE × race or ethnicity: No effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Those with household incomes between $50,000 and $100,000 (p = .003) and ≥$100,000 (p = .015), greater internalizing scores (p < .001), and girls (p < .001) reported greater fear and worry.

Anger/Frustration

-

•

ACEs: Increased number of ACEs significantly predicted greater anger and frustration.

-

•

Time: Anger and frustration significantly decreased over time, with no ACE × time interaction.

-

•

Race/ethnicity: Race was significantly related to anger/frustration. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, Black youths reported less anger and frustration.

-

•

ACE × race or ethnicity × time: No other effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Girls (p < .001) and those with household incomes ≥$100,000 (p = .02) and greater internalizing scores (p < .001) reported more anger and frustration.

Perceived Stress Scale-4

-

•

ACEs: Increased number of ACEs significantly predicted greater perceived stress.

-

•

Time: Perceived stress significantly decreased over time, with no ACE × time interaction.

-

•

Race/ethnicity and ACE × race or ethnicity × time: No effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Older youths, girls, and those with greater internalizing scores (p values < .001) reported greater perceived stress.

Primary Findings: COVID-19–Specific Mental Health Outcomes

Coronavirus Health Impact Survey COVID-19 Worry

-

•

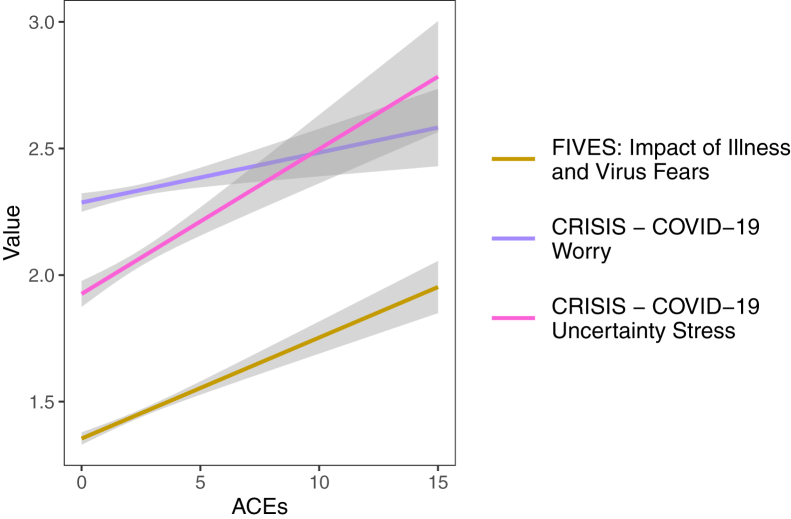

ACEs: ACEs did not significantly predict COVID-19–related worry (Table 3 and Figure 2).

-

•

Time: Worry significantly decreased over time, with no ACE × time interaction.

-

•

Race/ethnicity: Race and ethnicity were significantly related to worry. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, Asian American and Black youths and youths from other racial or multiracial backgrounds reported greater COVID-19–related worry. Latinx youths also reported more COVID-19–related worry than non-Hispanic youths.

-

•

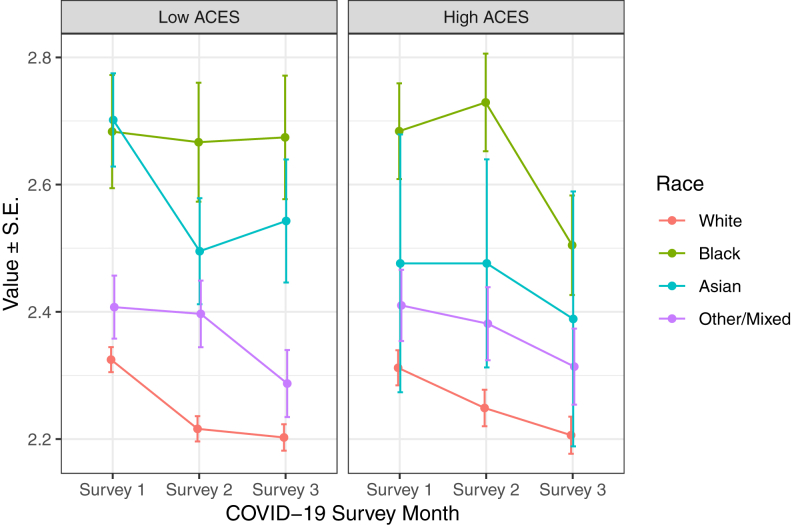

ACE × race × time: A significant three-way interaction showed that Black youths demonstrated unique patterns between ACEs and COVID-19–related worry across time. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, Black youths with a higher number of ACEs demonstrated a more robust reduction in peak worry from survey 2 to survey 3, while youths from other racial backgrounds had similar COVID-19 worry trajectories across ACE scores (Figure 3).

-

•

ACE × ethnicity × time: No effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Girls and those with family wage loss and greater internalizing scores (p values < .001) reported more COVID-19–related worry.

Table 3.

Predictors of Adolescent COVID-19–Related Mental Health Outcomes During COVID-19 Pandemic

| Outcome | Survey Time Point | Factors/Covariates | Estimate | SE | df | t | Uncorrected p Value | FDR p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Worry | Surveys 1–3 | ACEs | 0.013 | 0.010 | 12,230 | 1.11 | .27 | .57 |

| Time | −0.061 | 0.012 | 8233 | −5.06 | <.001 | |||

| ACE × time | −0.00094 | 0.0039 | 8225 | −0.24 | .81 | .85 | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.29 | 0.074 | 4336 | 3.94 | <.001 | |||

| Black | 0.40 | 0.047 | 4661 | 8.579 | <.001 | |||

| Other/multiracial | 0.099 | 0.034 | 4709 | 2.90 | .004 | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.14 | 0.085 | 10,190 | 1.61 | .02 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.068 | 0.077 | 12,500 | 0.87 | .38 | .67 | ||

| Black | 0.071 | 0.034 | 12,350 | 2.08 | .037 | .19 | ||

| Other/multiracial | −0.016 | 0.025 | 12,400 | −0.66 | .51 | .67 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | −0.0011 | 0.026 | 12,310 | −0.043 | .97 | .97 | ||

| ACE × race × time | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.029 | 0.030 | 7455 | −1.09 | .28 | .57 | ||

| Black | −0.039 | 0.014 | 8817 | −2.75 | .006a | .049 | ||

| Other/multiracial | 0.011 | 0.010 | 8053 | 1.12 | .26 | .57 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity × time | 0.0040 | 0.011 | 8347 | 0.369 | .71 | .85 | ||

| COVID-19 Stress | Survey 2 | ACEs | 0.033 | 0.010 | 3857 | 3.19 | .001a | .018 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.036 | 0.10 | 3230 | −0.35 | .73 | |||

| Black | 0.30 | 0.069 | 3278 | 4.41 | <.001 | |||

| Other/multiracial | 0.16 | 0.050 | 3416 | 3.167 | .002 | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.11 | 0.083 | 2763 | 1.32 | .19 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.016 | 0.069 | 3902 | −0.23 | .82 | .85 | ||

| Black | −0.024 | 0.031 | 3910 | −0.78 | .44 | .68 | ||

| Other/multiracial | 0.013 | 0.023 | 3815 | 0.56 | .58 | .77 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | −0.018 | 0.025 | 3824 | −0.73 | .47 | .69 | ||

| Impact of Virus Fears | Surveys 1 and 3 | ACEs | 0.091 | 0.019 | 6334 | 4.79 | <.001b | <.001 |

| Time | −0.096 | 0.035 | 4400 | −2.70 | .007 | |||

| ACE × time | −0.022 | 0.012 | 4317 | −1.93 | .053 | .19 | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.069 | 0.097 | 3443 | −0.72 | .47 | |||

| Black | 0.098 | 0.063 | 3886 | 1.57 | .12 | |||

| Other/multiracial | 0.095 | 0.046 | 4007 | 2.09 | .037 | |||

| Ethnicity | −0.0046 | 0.16 | 5801 | −0.03 | .98 | |||

| ACE × race | ||||||||

| Asian American | 0.080 | 0.14 | 5550 | 0.55 | .58 | .77 | ||

| Black | −0.017 | 0.066 | 6221 | −0.26 | .80 | .85 | ||

| Other/multiracial | 0.11 | 0.047 | 5833 | 2.32 | .02 | .13 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity | 0.052 | 0.050 | 6003 | 1.05 | .29 | .57 | ||

| ACE × race × time | ||||||||

| Asian American | −0.033 | 0.088 | 3650 | −0.37 | .71 | .85 | ||

| Black | −0.046 | 0.041 | 4818 | −1.11 | .27 | .57 | ||

| Other/multiracial | −0.059 | 0.029 | 4155 | −2.00 | .045 | .19 | ||

| ACE × ethnicity × time | −0.040 | 0.032 | 4502 | −1.25 | .21 | .57 |

ACE, adverse childhood experience; FDR, false discovery rate.

p < .05; p value remained significant after corrections.

p < .001; p value remained significant after corrections.

Figure 2.

Greater adverse childhood experience (ACE) scores relate to greater COVID-19–related stress and greater impact of virus fears during the COVID-19 pandemic. Graph shows bivariate relationship between ACE scores and COVID-19 specific outcomes (shaded portions represent standard error). The presented data for COVID-19 worry represents the mean worry scores (assessed at surveys 1–3) and mean impact of illness/virus fears scores (assessed at surveys 1 and 3) across time, while COVID-19 uncertainty stress represents mean scores at survey 2. As ACE scores increase, COVID-19 stress and impact of virus fears increase, while COVID-19 worry was not significantly associated with ACEs. CRISIS, Coronavirus Health Impact Survey; FIVES, Fear of Illness and Virus Evaluation Scale.

Figure 3.

Graphs shows changes in mean COVID-19 worry across time as a function of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (low vs. high) and race. While continuous variables were used in the ACE × race × time interaction, ACEs is presented as a categorical variable for visual graphing purposes.

Coronavirus Health Impact Survey COVID-19 Uncertainty Stress

-

•

ACEs: Greater number of ACEs significantly predicted more COVID-19–related uncertainty stress.

-

•

Race/ethnicity: Race was significantly related to stress. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, Black youths, and youths from other racial or multiracial backgrounds reported significantly more COVID-19–related uncertainty stress.

-

•

ACE × race or ethnicity: No effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Girls (p < .001) and those with family wage loss (p = .01) and greater internalizing scores (p < .001) reported more COVID-19 uncertainty stress.

Fear of Illness and Virus Evaluation Scale: Impact of Illness and Virus Fears

-

•

ACEs: Greater number of ACEs significantly predicted greater impact of virus fears on well-being.

-

•

Time: The impact of virus fears significantly decreased over time, with no ACE × time interaction.

-

•

Race/ethnicity: Race was significantly related to impact. Compared with non-Hispanic White youths, youths from other racial or multiracial backgrounds reported greater impact of the virus on their well-being.

-

•

ACE × race or ethnicity × time: No effects were significant.

-

•

Demographics: Girls and those with higher internalizing scores (p values < .001) reported greater impact of virus-related fears, and those with parents with a high-school diploma (p = .02), some college (p = .02), and bachelor’s (p = .008) and postgraduate degrees reported less impact (p = .01).

Discussion

Prior research has shown that experiencing childhood adversity predicts mental health trajectories from adolescence to adulthood (18, 30, 31), which likely relates to how experiencing adversity affects future responses to environmental stressors (32, 33). Hence, this study examined the relationship between pre-pandemic ACEs and affective state and mental health in youth during a large-scale stressor, the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that in a diverse group of youths enrolled in the longitudinal ABCD Study, greater ACEs measured before the COVID-19 pandemic significantly predicted greater negative mood symptoms and COVID-19–related stress and fear during the first months after the pandemic onset (spring and summer 2020) after controlling for demographics, internalizing symptoms, and co-occurring COVID-19 family and school stressors. Youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds experienced differential relationships between ACEs and COVID-19–related worry. We also identified that other factors, including race, ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, internalizing symptoms, and age, were also linked with mental health and COVID-19–related distress during the pandemic.

Specifically, greater ACEs predicted greater past-week sadness, fear, and anger; past-month perceived stress; and lower levels of past-week positive affect in a dose-dependent fashion, with effect sizes ranging from small to medium. As ACE risk scores increased, youths reported significantly greater COVID-19–related stress and impact of COVID-19 fear on their daily lives, with more subtle, smaller effect sizes. These findings are consistent with results from other studies during the pandemic (34, 35, 36, 37, 38) and suggest that contributions of childhood stressors or trauma experiences have a predictive relationship with preadolescent/adolescent mental health during the pandemic in the United States. Notably, longitudinal analyses accounted for pre-pandemic internalizing symptoms, suggesting that the mood symptoms experienced during the pandemic are not simply a continuation of premorbid distress levels. In a promising trend, mood symptoms and COVID-19–related distress improved across the three waves of data collection from May to August 2020. These improvements in mood and mental health across the early months of the pandemic could be explained by how individuals exposed to early-life stress may differ in their susceptibility to improvements in stressors (67). Still, findings primarily suggest that adolescents and preadolescents who have experienced elevated ACEs should be targeted for prevention and intervention efforts as the field attempts to reduce the negative mental health consequences of the pandemic.

Our secondary aim was to examine whether youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds experienced a stronger relationship between ACEs and mental health symptoms during the pandemic. Across general mood and mental health outcomes, we did not find that race or ethnicity moderated these relationships. However, significant main effects of race/ethnicity and ACE × race interactions, with small effect sizes, were found for COVID-19–specific worry, stress, and impact of virus fears. Findings showed that youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds reported greater COVID-19 worry, wherein Black youths with higher ACEs reported greater COVID-19–related worry at survey 2 than non-Hispanic White youths. Black youths and youths from other racial or multiracial backgrounds also reported greater COVID-19 stress and impact of fears on well-being than non-Hispanic White youths. While these race findings typically had smaller effect sizes or did not stand after corrections, small effect sizes in large samples may have meaningful impact in prevention work when replicated. Therefore, replication of these findings is warranted to better understand potential racial or ethnic differences in mental health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure that scientific and clinical communities are addressing potential health disparities.

One potential explanation for elevated COVID-19–related distress in youths from minoritized communities is their families’ increased exposure to the effects of COVID-19 (48, 49, 50, 51). Within some minoritized racial-ethnic communities (i.e., Black, Latinx, and some indigenous groups), COVID-19–related health disparities have been documented in elevated risk for infection, hospitalization, and mortality (42, 43, 44, 45). While not directly assessed, these findings may reflect the repercussions of generations of multilevel systemic inequalities that disproportionately affect some minoritized communities (e.g., Black and Latinx), where COVID-19 circumstances compound on existing stressors (50,68). In these communities, greater risk for underlying conditions that exacerbate COVID-19, limited health care access (e.g., COVID-19 testing, vaccines, and treatment), and overrepresentation in essential workers are likely contributors to COVID-19 racial-ethnic health disparities (69). Another contributor to elevations in COVID-19–related distress could be minoritized racial-ethnic youths' experiences of racial discrimination during COVID-19. However, during the pandemic, minoritized racial-ethnic groups have likely experienced racial discrimination but for different reasons. Specifically, Asian Americans have experienced greater discrimination related to the virus, while Black individuals have faced increased discrimination due to societal responses to the Black Lives Matter movement (70). Consistent with this hypothesis, youths from minoritized racial backgrounds reported greater COVID-19-related discrimination, and experiencing COVID-19–related racial discrimination was a significant predictor of COVID-19–related worry (see the Supplement). These specific differences in COVID-19–related mental health symptoms in youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds suggest that they are experiencing unique COVID-19 distress and increased incidents of racial discrimination. Culturally sensitive mental health interventions that target COVID-19–related concerns and integrate cultural and contextual factors are needed (71).

While the primary focus of this study was on ACEs and interactions with race and ethnicity, other factors including demographics (i.e., sex) and internalizing symptoms, were robust predictors of pandemic mental health. One of the most consistent predictors was pre-pandemic internalizing symptoms. Increased pre-pandemic internalizing symptoms predicted increased sadness; fear; anger; perceived stress; COVID-19–related worry, stress, and fear; and reduced positive affect. This aligns with findings of early internalizing problems predicting adolescent mental health trajectories (72) and emphasizes the public health need for early screening for childhood and preadolescent mental health symptoms, especially during the current pandemic.

Notably, a significant effect of sex assigned at birth was observed, where female youths reported significantly poorer mood and greater distress on COVID-19–related measures compared with male youths. Current findings align with studies that have observed significant sex differences in mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic (4,73). These findings may reflect the interaction of documented increases in internalizing symptoms in girls (74,75) co-occurring with additional pandemic stress. While not a primary focus of this investigation, future research is warranted to examine the sex effects related to mental health during COVID-19.

This study is not without limitations. Within the ABCD Study design, more direct assessments of some ACEs were included (e.g., household substance use); however, some ACE categories were determined through proxy variables (e.g., emotional neglect assessed through youths’ perceptions of caregiver warmth) (see the Supplement). Furthermore, the presented scoring for ACEs did not account for experiences that may have occurred between 1-year follow-up and first COVID-19 impact survey. Other factors, such as frequency, timing, or severity of ACEs, were not measured. Given the impact of ACEs here, future research should include more explicit assessment of ACEs that can tease apart the unique impact of frequency, severity, and timing of events. This study sample was also undersampled in minoritized populations and low-income families relative to the overall ABCD Study cohort (51). Furthermore, the ABCD Study was not designed to disentangle multifaceted associations between developmental outcomes and race/ethnicity; accordingly, ABCD assessments about race and ethnic identity are not exhaustive and are often conflated with nationality. Limited measurements of racial-ethnic identity led ABCD to collapse across undersampled racial groups, likely minimizing other-group differences in COVID-19 pandemic experiences in addition to implying that experiences across groups are homogeneous. Future research addressing health disparities should prioritize proportional representation of individuals from minoritized racial-ethnic groups. While this study accounted for some co-occurring COVID-19–related stressors (i.e., family job/wage loss and changes in school environment), other stressors such as experiencing household pandemic-related illness or the severity or timing of COVID-19 stressors were not included. To further understand potential public health disparities, incorporating geocoded data that include COVID-19 severity rates, hospital capacity, access to testing and vaccines, and public policy (e.g., mask mandates, stay-at-home orders) may help to elucidate mental health trajectories during the pandemic in future work. Finally, these findings were assessed during the summer of 2020, and rapid changes in the fall of 2020, such as differential school openings and closings and significant increases in virus cases, could affect reports of mental well-being; thus, research with more assessment points is necessary. To highlight study strengths, the ABCD Study sample is the largest and most diverse preadolescent/adolescent sample used to date to examine how pre-pandemic exposure to ACEs may predict mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, experiencing childhood adversity before the pandemic was consistently associated with poorer mood and mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds experienced greater distress on COVID-19–related outcomes, with an ACE × race interaction being found for experiences of COVID-19 worry. Notably, across the early months of the pandemic onset (summer 2020), youth reported improvements in mental health, suggesting potential resiliency as the pandemic continues. These study findings provide support for early assessment of ACEs to address the pandemic-related mental health crisis in youth, with particular focus given to youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds, who reported more COVID-19–related distress and discrimination. From a public health perspective, results highlight the urgency for schools, mental health clinics, and pediatricians to partner with parents and community leaders to screen adolescents with ACE history for emerging mental health needs. Although youths from minoritized racial-ethnic backgrounds demonstrated resilient general mental health, results suggest that culturally sensitive prevention and intervention efforts aimed at alleviating COVID-19–related distress in minoritized youths are also a public health priority.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive (NDA). The ABCD Study is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9–10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under Grant Nos. U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. The ABCD COVID-19 Substudy is supported by the National Institutes of Health and federal partners (Grant Nos. U24DA041147-06S5, U24DA041147-06S1, and U24DA041123-06S1), funding from the National Science Foundation (principal investigator: SFT; Grant No. NSF-2028680), and funding from the Institute of Digital Media and Child Development Inc. (principal investigator: SFT). ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in analysis or writing of this report.

This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the National Institutes of Health or ABCD consortium investigators.

https://abcdstudy.org The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from the ABCD 3.0 data release (https://doi.org/10.15154/1519007) and the ABCD COVID-19 Survey First Data Release (https://doi.org/10.15154/1520584). DOIs can be found at https://nda.nih.gov/study.html?id=901 and https://nda.nih.gov/study.html?&id=1041.

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.08.007.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Bignardi G., Dalmaijer E.S., Anwyl-Irvine A.L., Smith T.A., Siugzdaite R., Uh S., Astle D.E. Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Dis Child. 2020;106:791–797. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie X., Xue Q., Zhou Y., Zhu K., Liu Q., Zhang J., Song R. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:898–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou S.J., Zhang L.G., Wang L.L., Guo Z.C., Wang J.Q., Chen J.C., et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29:749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen F., Zheng D., Liu J., Gong Y., Guan Z., Lou D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:36–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breaux R., Dvorsky M.R., Marsh N.P., Green C.D., Cash A.R., Shroff D.M., et al. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62:1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly M., Sutin A.R., Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study [published online ahead of print Nov 13] Psychol Med. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu C.H., Zhang E., Wong G.T.F., Hyun S., Hahm H.C. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for US young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113172. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ettman C.K., Abdalla S.M., Cohen G.H., Sampson L., Vivier P.M., Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vahia I.V., Jeste D.V., Reynolds C.F., 3rd Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:2253–2254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnett J.J. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. Am Psychol. 1999;54:317–326. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19 [published correction appears in Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020; 4:e16] Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang G., Zhang Y., Zhao J., Zhang J., Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:945–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiao W.Y., Wang L.N., Liu J., Fang S.F., Jiao F.Y., Pettoello-Mantovani M., Somekh E. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. 2020;221:264–266.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fegert J.M., Vitiello B., Plener P.L., Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravens-Sieberer U., Kaman A., Erhart M., Devine J., Schlack R., Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany [published online ahead of print Jan 25] Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cost K.T., Crosbie J., Anagnostou E., Birken C.S., Charach A., Monga S., et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents [published online ahead of print Feb 26] Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D.F., Spitz A.M., Edwards V., et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlin K.A., Greif Green J., Gruber M.J., Sampson N.A., Zaslavsky A.M., Kessler R.C. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1151–1160. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee E., Larkin H., Esaki N. Exposure to community violence as a new adverse childhood experience category: Promising results and future considerations. Fam Soc. 2017;98:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afifi T.O. In: Adverse Childhood Experiences. Asmundson G.J.G., Afifi T.O., editors. Academic Press; Cambridge: 2020. Considerations for expanding the definition of ACEs; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronholm P.F., Forke C.M., Wade R., Bair-Merritt M.H., Davis M., Harkins-Schwarz M., et al. Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruner C. ACE, place, race, and poverty: Building hope for children. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:S123–S129. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernard D.L., Calhoun C.D., Banks D.E., Halliday C.A., Hughes-Halbert C., Danielson C.K. Making the “C-ACE” for a culturally informed adverse childhood experiences framework to understand the pervasive mental health impact of racism on Black youth. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2020;14:233–247. doi: 10.1007/s40653-020-00319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vig K.D., Paluszek M.M., Asmundson G.J.G. In: Adverse Childhood Experiences. Asmundson G.J.G., Afifi T.O., editors. Academic Press; Cambridge: 2020. ACEs and physical health outcomes; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nurius P.S., Green S., Logan-Greene P., Longhi D., Song C. Stress pathways to health inequalities: Embedding ACEs within social and behavioral contexts. Int Public Health J. 2016;8:241–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicchetti D., Rogosch F.A. Diverse patterns of neuroendocrine activity in maltreated children. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:677–693. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carpenter L.L., Carvalho J.P., Tyrka A.R., Wier L.M., Mello A.F., Mello M.F., et al. Decreased adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol responses to stress in healthy adults reporting significant childhood maltreatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1080–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLaughlin K.A., Weissman D., Bitrán D. Childhood adversity and neural development: A systematic review. Annu Rev Dev Psychol. 2019;1:277–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-084950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaughlin K.A., Sheridan M.A., Lambert H.K. Childhood adversity and neural development: Deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;47:578–591. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark C., Caldwell T., Power C., Stansfeld S.A. Does the influence of childhood adversity on psychopathology persist across the lifecourse? A 45-year prospective epidemiologic study. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nurius P.S., Green S., Logan-Greene P., Borja S. Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: A stress process analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;45:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammen C., Henry R., Daley S.E. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLaughlin K.A., Conron K.J., Koenen K.C., Gilman S.E. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo J., Fu M., Liu D., Zhang B., Wang X., van Ijzendoorn M.H. Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110:104667. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chi X., Becker B., Yu Q., Willeit P., Jiao C., Huang L., et al. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of mental health outcomes among Chinese college students during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seitz K.I., Bertsch K., Herpertz S.C. A prospective study of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood trauma-exposed individuals: Social support matters. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34:477–486. doi: 10.1002/jts.22660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gotlib I.H., Borchers L.R., Chahal R., Gifuni A.J., Teresi G.I., Ho T.C. Early life stress predicts depressive symptoms in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of perceived stress. Front Psychol. 2021;11:603748. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.603748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doom J.R., Seok D., Narayan A.J., Fox K.R. Adverse and benevolent childhood experiences predict mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print Apr 23] Advers Resil Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s42844-021-00038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacks V., Murphey D. The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, nationally, by state, and by race or ethnicity. 2018. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/prevalence-adverse-childhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity Available at:

- 40.Giano Z., Wheeler D.L., Hubach R.D. The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1327. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09411-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maguire-Jack K., Lanier P., Lombardi B. Investigating racial differences in clusters of adverse childhood experiences. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90:106–114. doi: 10.1037/ort0000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossen L.M., Branum A.M., Ahmad F.B., Sutton P., Anderson R.N. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19, by age and race and ethnicity—United States, January 26–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1522–1527. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tai D.B.G., Shah A., Doubeni C.A., Sia I.G., Wieland M.L. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:703–706. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khazanchi R., Beiter E.R., Gondi S., Beckman A.L., Bilinski A., Ganguli I. County-level association of social vulnerability with COVID-19 cases and deaths in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:2784–2787. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html Available at:

- 46.Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fitzpatrick K.M., Harris C., Drawve G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S17–S21. doi: 10.1037/tra0000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Condon E.M., Dettmer A.M., Gee D.G., Hagan C., Lee K.S., Mayes L.C., et al. Commentary: COVID-19 and mental health equity in the United States. Front Sociol. 2020;5:584390. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.584390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Purtle J. COVID-19 and mental health equity in the United States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:969–971. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01896-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bambra C., Riordan R., Ford J., Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74:964–968. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fortuna L.R., Tolou-Shams M., Robles-Ramamurthy B., Porche M.V. Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: The need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:443–445. doi: 10.1037/tra0000889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volkow N.D., Koob G.F., Croyle R.T., Bianchi D.W., Gordon J.A., Koroshetz W.J., et al. The conception of the ABCD study: From substance use to a broad NIH collaboration. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jernigan T.L., Brown S.A., ABCD Consortium Coordinators Introduction. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garavan H., Bartsch H., Conway K., Decastro A., Goldstein R.Z., Heeringa S., et al. Recruiting the ABCD sample: Design considerations and procedures. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barch D.M., Albaugh M.D., Avenevoli S., Chang L., Clark D.B., Glantz M.D., et al. Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study: Rationale and description. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lisdahl K.M., Sher K.J., Conway K.P., Gonzalez R., Feldstein Ewing S.W., Nixon S.J., et al. Adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: Overview of substance use assessment methods. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zucker R.A., Gonzalez R., Feldstein Ewing S.W., Paulus M.P., Arroyo J., Fuligni A., et al. Assessment of culture and environment in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study: Rationale, description of measures, and early data. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoffman E.A., Clark D.B., Orendain N., Hudziak J., Squeglia L.M., Dowling G.J. Stress exposures, neurodevelopment and health measures in the ABCD study. Neurobiol Stress. 2019;10:100157. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karcher N.R., Niendam T.A., Barch D.M. Adverse childhood experiences and psychotic-like experiences are associated above and beyond shared correlates: Findings from the adolescent brain cognitive development study. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Evans G.W., Li D., Whipple S.S. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:1342–1396. doi: 10.1037/a0031808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Achenbach T.M. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2009. The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): Development, Findings, Theory, Applications. Accessed March 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ehrenreich-May J (2020): Fear of Illness and Virus Evaluation (FIVE) – Child Report Form. Available at https://adaa.org/sites/default/files/UofMiamiFear%20of%20Illness%20and%20Virus%20Evaluation%20(FIVE)%20scales%20for%20Child-%2C%20Parent-%20and%20Adult-Report..pdf. Accessed January 4, 2021.

- 64.R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B (Methodol) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Albott C.S., Forbes M.K., Anker J.J. Association of childhood adversity with differential susceptibility of transdiagnostic psychopathology to environmental stress in adulthood. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e185354. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams D.R., Cooper L.A. COVID-19 and health equity—A new kind of “herd immunity”. JAMA. 2020;323:2478–2480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Artiga S., Garfield R., Orgera K. Communities of color at higher risk for health and economic challenges due to COVID-19. 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/communities-of-color-at-higher-risk-for-health-and-economic-challenges-due-to-covid-19/ Available at:

- 70.Ruiz N.G., Horowitz J.M., Tamir C. Many Black and Asian Americans say they have experienced discrimination amid the COVID-19 outbreak. 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/07/01/many-black-and-asian-americans-say-they-have-experienced-discrimination-amid-the-covid-19-outbreak/ Available at:

- 71.Trent M., Dooley D.G., Dougé J., SECTION ON ADOLESCENT HEALTH, COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS, COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics. 2019;144 doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goodwin R.D., Fergusson D.M., Horwood L.J. Early anxious/withdrawn behaviours predict later internalising disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:874–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Magson N.R., Freeman J.Y.A., Rapee R.M., Richardson C.E., Oar E.L., Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50:44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gutman L.M., Codiroli McMaster N. Gendered pathways of internalizing problems from early childhood to adolescence and associated adolescent outcomes. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2020;48:703–718. doi: 10.1007/s10802-020-00623-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mendle J. Why puberty matters for psychopathology. Child Dev Perspect. 2014;8:218–222. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.