Abstract

Sinusitis is a common ailment a clinician comes across in their day-to-day practice. Simple as it may sound, it may become a very debilitating condition depending on the comorbidities of the patient and the organism involved. Rhizopus and Escherichia coli are less common organisms to affect the sinuses, but they are more common in immunocompromised patients such as patients with uncontrolled diabetes. Rhizopus can be a very debilitating infection as it erodes into the bone and blood vessels resulting in tissue necrosis. However, coinfection of both of these organisms is a very rare occurrence. Psoas abscess is also a less common infection in the immunocompetent patients but it is more common among the immunocompromised patients. It is extremely rare for both of these organisms to cause sinusitis in one patient, and for E. coli to simultaneously infect two different sites in the same patient. We report a case where a diabetic patient who had E. coli and Rhizopus coinfected sinusitis with simultaneous E. coli psoas abscess was successfully managed. The Rhizopus was treated with liposomal amphotericin B for 16 weeks while E. coli was treated with IV Meropenum. Furthermore, pneumocephalus is a condition that usually occurs following head trauma but the patient we are reporting developed pneumocephalus following Rhizopus sinusitis, which was treated with high-flow oxygen.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, E. coli, mucormycosis, pneumocephalus, psoas abscess, sinusitis

Introduction

Sinusitis is a common ailment a clinician comes across in their day-to-day practice. However, simple as it may sound, it may become a very debilitating condition depending on the comorbidities of the patient and the organism involved.

Commonest organisms are viruses and bacteria. Out of the bacterial infections Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae account for the majority whereas Escherichia coli is considered to be one of the least common organisms to cause sinusitis [1]. However, samples are not usually taken from sinuses for culture when treating sinusitis, and is treated empirically [2].

Mucormycosis is a unifying term used for infections caused by fungi of the order Mucorales. It is an opportunistic infection affecting immunocompromised patients [3], especially patients with uncontrolled diabetes.

Poor hygiene, low socioeconomic status, hot and humid climate and presence of preexisting suppurative conditions are known associations that increase the risk of mucormycosis [4]. The organisms that cause mucormycosis are saprophytic fungii. It affects many organs of the body, commonly affecting paranasal sinuses, lungs and skin, and less commonly the gut [5]. The hallmark of pathogenesis of mucormycosis is angioinvasion. It attaches to the endothelium of the blood vessels resulting in endothelial damage. This subsequently results in extensive thrombosis of the invaded vessels and necrosis of the tissue supplied by the vessels [6].

Iliopsoas is a retroperitoneal compartment, which comprises the iliacus and psoas muscles on either side of the vertebral column. An abscess in this compartment is known as an iliopsoas abscess. This usually occurs via haematogenous spread [7]. Iliopsoas abscess is a rare condition in the western world, but it is more prevalent in the south Asian region. The commonest organism to cause psoas abscess is Staphylococcus aureus, while E. coli is one of the less common organisms [8].

We report a case of a diabetic patient presenting with mucormycosis and E. coli coinfection in the sinuses complicated with pneumocephalus, with a simultaneous E. coli psoas abscess, and was treated successfully.

Case report

A 61-year-old lady, from Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka, with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus over 8 years presented with fever and headache. She complained of severe anorexia, lethargy and she was apathetic. Her glycaemic control was poor. On examination, she was dehydrated, very ill looking and had an erythematous patch over the right maxillary bone, which was very tender. She had very high neutrophil leukocytosis on full blood count (FBC) and her C-reactive protein (CRP) was above 200 mg l−1. Her x-ray of occipito-mental (OM) view revealed opacity in her right maxillary sinus. Bacterial sinusitis was suspected and intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone was initiated after obtaining blood for culture. Her blood sugar was effectively controlled with insulin, initially with infusion followed by basal bolus regime [9]. Her blood sugar was maintained between 140–180 mg dl−1 during the acute critical period. Urinary ketone bodies were tested twice and it was found to be negative both times. Further she was referred to the ear–nose–throat (ENT) team for an antral washout and the antral wash samples were sent for bacterial and fungal culture. The ENT team reported that there was no identifiable necrotic material in the right maxillary sinus.

Meanwhile, the patient deteriorated clinically and the blood pressure plummeted. As a result, she was admitted to the intensive care unit and was managed as septic shock with IV fluids and noradrenalin. The blood culture and the sinus washout culture both grew E. coli. Blood culture was processed using an automated blood culture system (BD BacTecTM, USA). After signalled positive, it was plated-on blood, chocolate and MacConkey agar using standard microbiological procedures. After overnight incubation, the colonies were identified using an automated bacterial identification system (BD PhoenixTM, USA).

The sinus fluid specimen was plated on plated-on blood, chocolate and MacConkey agar using standard microbiological procedures. After overnight incubation, the colonies were identified using an automated bacterial identification system (BD PhoenixTM, USA).

The antibiotic was converted to IV Meropenum 1 g three times daily as the clinical condition was deteriorating and as the organism was sensitive to meropenem. Four days later the sinus washout fungal culture grew Rhizopus. The direct microscopy examination of the natal washout received for fungal studies showed broad, folded ribbon‐like, non-septate fungal filaments with right‐angle branching. The rest of the specimen was inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar with chloramphenicol (at 37 and 26 °C) for culture.

A white aerial mould with black heads grew up to the lid of the culture bottles after 5 days of incubation. Wide, nonseptate hyaline hyphae along with pigmented rhizoids, sporangiophores, sporangia and sporangiospores were observed in the lactophenol cotton blue mount of the growth. Sporangiophores along with sporangia on their tips, located on the nodes directly above the rhizoids. Sporangia were globose, multispored and had hemispherical columellae. Sporangiospores were ovoid, hyaline to light brown, and slightly rough. The above morphological features were in line with Rhizopus arrhizus and the isolate was identified as R. arrhizus. By this time, the skin over the right maxillary bone was becoming necrotic (Fig. 1). Therefore the patient was administered liposomal amphotericin B antifungal drug 3 mg/kg/day.

Fig. 1.

Necrotic skin over the maxillary sinus.

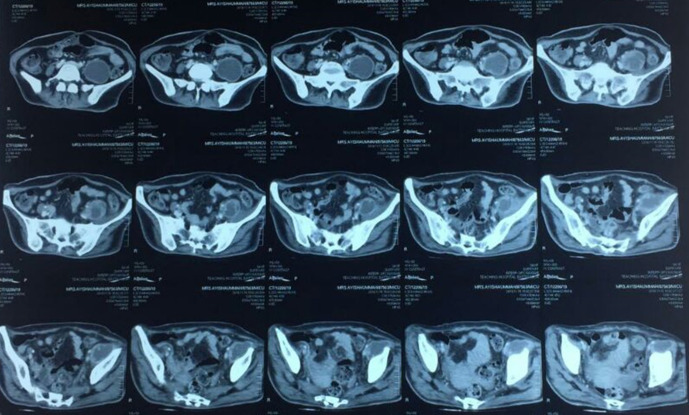

An ultrasound scan (USS) of the abdomen and a chest x-ray was arranged as the patient did not show significant improvement despite adequate antibiotic cover (3 days of IV Ceftriaxone and 6 days of IV Meropenum). It revealed a left-sided psoas abscess and a contrast enhanced CT (CECT) of the abdomen was done to confirm the abscess and to assess the extent of it (Fig. 2). The patient did not have any signs and symptoms corresponding to a psoas abscess. The abscess was aspirated under USS guidance and the samples were sent for bacterial culture and for direct microscopy for acid fast bacilli (AFB).

Fig. 2.

Left-sided psoas abscess (white arrow).

A repeat USS of the psoas abscess after 5 days revealed recollection of the abscess and again it was aspirated under USS guidance. The flexible rhinoscopy was repeated for an antral washout and at this point it revealed necrotic debris, which were removed. Even after 2 weeks of amphotericin B, the bone of the maxillary sinus was getting eroded progressively including the orbital cavity. Therefore the dose was increased to 5 mg/kg/day. There was also recurrent recollection of the psoas abscess. Hence, the psoas abscess was drained surgically after which, there was significant improvement clinically, biochemically and haematologically.

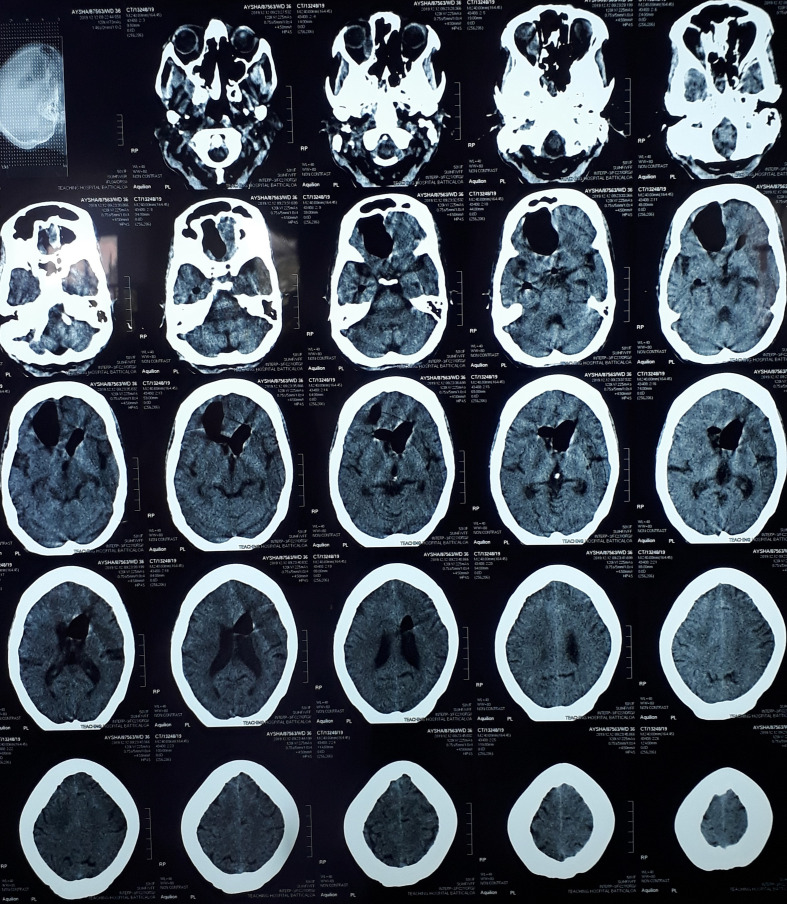

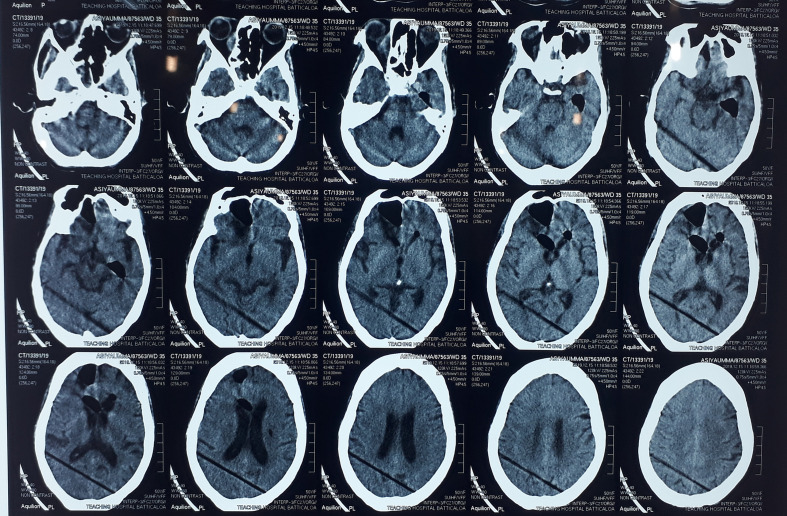

On the fourth week of presentation, 2 days after a flexible rhinoscopy, the patient’s conscious level suddenly deteriorated. Her metabolic screening was normal. The non-contrast computerized topography (NCCT) of the brain revealed pneumocephalus (Fig. 3). Air was seen in the cerebrum, anterior horns of the lateral ventricles and around the pituitary stalk. The patient was put on high-flow oxygen and the patient’s conscious level improved after 4 days. NCCT brain was repeated after 6 days of the first CT, which demonstrated improvement of the pneumocephalus by more than 50% (Fig. 4). We continued to administer oxygen for another 1 week until the pneumocephalus was completely reabsorbed.

Fig. 3.

NCCT brain revealing pneumocephalus.

Fig. 4.

NCCT brain after 6 days of high-flow oxygen. Pneumocephalus has improved.

We continued amphotericin B until the cumulative dose is 5 g and the Meropenum for 6 weeks until the patient completely recovered clinically, biochemically and haematologically. A flexible rhinoscopy was done at the end of the treatment and it did not reveal any necrotic material. Finally, the patient was referred for facial reconstruction surgery.

Discussion

The discussion will be done under the following four main areas.

Diabetes mellitus and sinusitis

Mucormycosis sinusitis and treatment,

Mucormycosis sinusitis induced pneumocephalus and treatment

Simultaneous E. coli sinusitis and psoas abscess

It is a well-known fact that diabetic patients have poor immunity and are more prone to infections, especially when the glycaemic control is poor. The rate of overall infection is proportionate to the mean serum glucose level of the patient. Furthermore, good sugar control in diabetic patients is important to maintain a normal host defence system [10]. Sinusitis is a common condition usually treated with antibiotics without culturing the sinuses [2]. Simple as it may sound, we would like to point out that even a simple condition like sinusitis may end up at a debilitating level in a diabetic due to the poor immune system. Extra care should be taken when treating sinusitis in diabetic patients where they can harbour rarer organisms such as E. coli [1] and Mucorales, such as the patient in this discussion. Furthermore, the clinician should be mindful regarding the possibility of dual causative agents simultaneously.

Mucormycosis of maxillary sinus is a very serious and enfeebling condition. The prevalence of Mucormycosis is higher in South Asia compared to the western world. For example, in India and Pakistan it is 14 per 100 000 whereas in the UK it is 0.09, and in the USA it is 0.3 [11]. Mucormycosis commonly occurs in immunocompromised patients and mucormycosis involving the sinuses is common [12]. Furthermore, mucormycosis can occur as a secondary infection over a suppurative infection [4], as in the case of our patient. The drug of choice for mucormycosis is amphotericin B. However, the deoxycholate preparation of amphotericin B is nephrotoxic. The newer lipid preparations of amphotericin B is less nephrotoxic. There are three types of lipid formulations of amphotericin B: liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC) and amphotericin B colloidal dispersion (ABCD) [13]. Our patient was initially treated with 3 mg kg−1 daily dose of liposomal amphotericin B but as the patient did not show significant improvement, the dose was increased to 5 mg kg−1 and was continued up to cumulative dose of 5 g. Larkin and Montero have treated 64 immunocompromised patients suffering from mucormycosis with ABLC. The median daily dose has been 4.8 mg kg−1 and the median duration has been 16 days. The overall favourable clinical response has been 72 and 64% have had a success rate among the patients with disseminated disease [14]. In another study conducted by Walsh et al. 17 out of 24 patients treated for mucormycosis have shown complete or partial response to ABLC [15]. Managing mucormycosis needs a multidisciplinary approach. However, there are no guidelines on the duration of treatment with amphotericin B in mucormycosis. The treatment is individualized to suit the patient [16]. The removal of necrotic debris is imperative even though it may leave the patient disfigured. We based the duration depending on the treatment response and the cumulative dose. The treatment response was assessed using clinical response, biochemical and haematological parameters, findings from serial flexible rhinoscopies and radiological and mycological cure. Once the infection has been cleared, complete facial reconstruction has to be employed.

As we stated above, mucormycosis is a quite serious and a debilitating condition with many dire complications. Cavernous sinus thrombosis and invasion of the orbital cavity are two serious complications and they carry very high morbidity and mortality [17]. Our patient developed a pneumocephalus, which is a very rare or in fact a condition that has not been previously reported. Commonly, pneumocephalus occurs following trauma or sugery [18]. In this case, pneumocephalus could have occurred due to the fungus eroding into the bone, subsequently reaching the intracranial cavity. Air in the pituitary stalk suggested that the air might have entered from the sphenoidal sinus as a result of invasion of the fungus. The removal of fungal debris from the sinuses and the nasal cavity may have also been a contributory factor. However, even though the fungus eroded into the bone extensively, it did not invade the cavernous sinus. We believe that timely and aggressive treatment with amphotericin B was instrumental in preventing the fungus reaching the cavernous sinus. The treatment for pneumocephalus resulting from mucormycosis was high-flow oxygen. The atmospheric air is composed of 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen. The rate of nitrogen absorption from pneumocephalus depends on the partial pressure of nitrogen in the blood, which is inversely proportional to the FiO2. When clinicians supplement oxygen, the nitrogen concentration in blood and brain tissue is reduced, increasing the nitrogen concentration gradient between the pneumocephalus and the brain tissue for absorption. As a result, the pneumocephalus will slowly come to comprise only of oxygen, which has got high solubility within brain tissue and blood leading to complete resorption of the pneumocephalus [19].

Psoas abscess is not a rare condition, especially in diabetic patients. However, a psoas abscess occurring simultaneously with sinusitis with the same organism is quite rare. It commonly results from haematological spread and can be primary or secondary. Primary psoas abscesses occur through haematological spread of an infection from an occult source, and secondary infection can occur from various foci with Crohn’s disease being the commonest [20]. It is believed that in our patient E. coli infection originated in the sinuses, which led to a psoas abscess via hematologic spread. The predisposing condition was poor immunity due to uncontrolled diabetes mellitus where the host’s immune response is disrupted and the natural barrier is damaged due to neuropathy [21]. Treating a psoas abscess is a therapeutic challenge. As in our patient, it is treated with broad spectrum antibiotics, and percutaneous or open drainage or combination of both [22]. If it was drained via percutaneous needle aspiration, repeat USSs are needed to assess the recurrence.

We hypothesized, taking into consideration the whole disease process of this patient, that the initial infection would have been the sinusitis with E. coli, which was complicated with psoas abscess via haematological spread. Mucormycosis is a superadded infection in the sinuses as it may occur as a secondary infection over an existing suppurative infection [4]. The mucormycosis sinusitis was complicated with pneumocephalus. However, none of these infections could have been controlled if the blood sugar was not under control. The patient’s glycaemic control was of paramount importance in controlling the infections.

In conclusion, the following messages have to be conveyed.

Simple conditions such as sinusitis can become very complicated in such ways that there can be co-infections with bacteria and fungus, and the clinician should be vigilant to suspect a secondary infection when a diabetic patient is not responding to the treatment.

Pneumocephalus is a complication to look out for in diabetic patients with mucormycosis sinusitis and should be treated with high flow oxygen.

Patients with mucormycosis should be timely and aggressively treated with liposomal amphotericin B and the duration of the treatment depends on the clinical, radiological and mycological improvement of the patient and the cumulative dose of liposomal amphotericin B.

Multiple sites of infections should be suspected in diabetic patients who fail to respond to adequate antibiotic treatment even though they are asymptomatic.

Glycaemic control is of paramount importance when treating infections in diabetic patients.

Funding information

The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

Consent to publish has been obtained.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ABCD, amphotericin B colloidal dispersion; ABLC, amphotericin B lipid complex; AFB, acid fast bacilli; CECT, contrast enhanced computerized topography; CRP, C reactive protein; E. coli, Escherichia coli; ENT, ear nose throat; FBC, full blood count; IV, intravenous; NCCT, non-contrast computerized topography; OM View, occipito-mental view; USS, ultrasound scan.

References

- 1.Hamory BH, Sande MA, Sydnor A, Seale DL, Gwaltney JM. Etiology and antimicrobial therapy of acute maxillary Sinusitis. J Infect Dis. 1979;139:197–202. doi: 10.1093/infdis/139.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolger WE. Gram negative Sinusitis: An emerging clinical entity? American Journal of Rhinology. 2018;8:279–284. doi: 10.2500/105065894781874205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilesh K, Vande AV. Mucormycosis of maxilla following tooth extraction in immunocompetent patients: Reports and review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2018;10:e300–e305. doi: 10.4317/jced.53655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manjunath NM, Pinto PM. Management of recurrent rhinomaxillary mucormycosis and nasal myiasis in an uncontrolled diabetic patient: A systematic approach. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2018;8:122–125. doi: 10.4103/ijabmr.IJABMR_22_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabhu RM, Patel R. Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis: a review of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 10:31–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim AS, Kontoyiannis DP. Update on mucormycosis pathogenesis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:508–515. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues J, Iyyadurai R, Sathyendra S, Jagannati M, Prabhakar Abhilash KP, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, management, and outcomes of iliopsoas abscess from a tertiary care center in South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6:836–839. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_19_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruenwald I, Abrahamson J, Cohen O. Psoas abscess: Case report and review of the literature. J Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37650-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petznick A. Insulin Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Am Fam Physician. 84:183–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson RM, Rice DH. Acute bacterial sinusitis and diabetes mellitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97:469–473. doi: 10.1177/019459988709700507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prakash H, Chakrabarti A. Global epidemiology of mucormycosis. J Fungi. 2019;5:26. doi: 10.3390/jof5010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szalai G, Fellegi V, Szabó Z, Vitéz LC. Mucormycosis mimicks sinusitis in a diabetic adult. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1084:520–530. doi: 10.1196/annals.1372.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chayakulkeeree M, Ghannoum MA, Perfect JR. Zygomycosis: The re-emerging fungal infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:215–229. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skiada A, Lanternier F, Groll AH, Pagano L, Zimmerli S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis in patients with hematological malignancies: guidelines from the 3rd European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL 3. Haematologica. 2013;98:492–504. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.065110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh TJ, Hiemenz JW, Seibel NL, Perfect JR, Horwith G, et al. Amphotericin B lipid complex for invasive fungal infections: analysis of safety and efficacy in 556 cases. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 26:1383–1396. doi: 10.1086/516353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kontoyiannis DP, Lewis RE. How I treat mucormycosis. Blood. 118:1216–1224. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-316430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernández JL, Buckley CJ. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019. Mucormycosis. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunqueiro A, Scheinfeld MH. Causes of pneumocephalus and when to be concerned about it. Emerg Radiol. 2018;25:331–340. doi: 10.1007/s10140-018-1595-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dabdoub CB, Salas G, Silveira E do N, Dabdoub CF. Review of the management of pneumocephalus. Surg Neurol Int [Internet] 2015;6 doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.166195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mallick IH, Thoufeeq MH, Rajendran TP. Iliopsoas abscesses. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:459–462. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.017665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berbudi A, Rahmadika N, Tjahjadi AI, Ruslami R. Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020;16:442–449. doi: 10.2174/1573399815666191024085838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabrizian P, Nguyen SQ, Greenstein A, Rajhbeharrysingh U, Divino CM. Management and treatment of iliopsoas abscess. Arch Surg. 2009;144:946–949. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]