Abstract

Objective

To explore what factors are associated with ambulance use for non-emergency problems in children.

Methods

This study is a systematic mapping review and qualitative synthesis of published journal articles and grey literature. Searches were conducted on the following databases, for articles published between January 1980 and July 2020: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and AMED. A Google Scholar and a Web of Science search were undertaken to identify reports or proceedings not indexed in the above. Book chapters and theses were searched via the OpenSigle, EThOS and DART databases. A literature advisory group, including experts in the field, were contacted for relevant grey literature and unpublished reports. The inclusion criteria incorporated articles published in the English language reporting findings for the reasons behind why there are so many calls to the ambulance service for non-urgent problems in children. Data extraction was divided into two stages: extraction of data to generate a broad systematic literature ‘map’, and extraction of data from highly relevant papers using qualitative methods to undertake a focused qualitative synthesis. An initial table of themes associated with reasons for non-emergency calls to the ambulance for children formed the ‘thematic map’ element. The uniting feature running through all of the identified themes was the determination of ‘inappropriateness’ or ‘appropriateness’ of an ambulance call out, which was then adopted as the concept of focus for our qualitative synthesis.

Results

There were 27 articles used in the systematic mapping review and 17 in the qualitative synthesis stage of the review. Four themes were developed in the systematic mapping stage: socioeconomic status/geographical location, practical reasons, fear of consequences and parental education. Three analytical themes were developed in the qualitative synthesis stage including practicalities and logistics of obtaining care, arbitrary scoring system and retrospection.

Conclusions

There is a lack of public and caregiver understanding about the use of ambulances for paediatrics. There are factors that appear specific to choosing ambulance care for children that are not so prominent in adults (fever, reassurance, fear of consequences). Future areas for attention to decrease ambulance activation for paediatric low-acuity reports were highlighted as: identifying strategies for helping caregivers to mitigate perceived risk, increasing availability of primary care, targeted education to particular geographical areas, education to first-time parents with infants and providing alternate means of transportation.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019160395.

Keywords: paediatrics, accident & emergency medicine, general medicine (see internal medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The review is highly inclusive, including a range of global study settings, including qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research.

This is the first mapping review specifically exploring ambulance use among paediatrics with problems that could be managed in primary care.

There is little evidence available addressing the specific question, reflected in the small number of studies suitable to the review criteria.

Much of the data is retrospective and therefore often incomplete and not recorded accurately.

Because of the limited evidence, the analysis is limited in areas.

Introduction

Despite an increasing range of urgent care options in the community, calls to the ambulance service continue to rise for ‘non-emergency’ problems.1 This is particularly apparent with calls to paediatric patients, which could be due to a multitude of factors.2 There is an absence of literature describing the factors associated with non-urgent ambulance/Emergency Medical Services (EMS) use for children.3 Demand for health services is increasing, and understanding patient motivations to seek healthcare may assist the development of demand management strategies.4

Growing numbers of people using emergency ambulances are leading to rising costs and increased pressure on resources,1 and are increasingly for calls that could be managed by an alternative healthcare provider (eg, primary care), that may be better placed to offer a time-optimised or resource-optimised response. Often, these calls are referred to in policy documents and academic literature as ‘inappropriate’, however, it is unclear if and how the concept of ‘inappropriate’ service use applies when considering children and ambulance calls. Previous work has focused on exploring and reducing ‘inappropriate’ use of ambulances, however the definition of ‘inappropriate’ is complex and nuanced (eg, 5). Literature exploring ‘inappropriate’ ambulance use for adults shows that unsuitable use is often determined by healthcare professionals retrospectively.6 Classifying calls as ‘inappropriate’ fails to recognise the context of the request for help and may be unhelpful for developing practical resolutions.7

There is an array of evidence exploring why adults use EMS for non-emergency problems, suggesting that patients define circumstances worthy of emergency health resources according to socioemotional factors, rather than for the symptoms underlying their illness.4 Reasons for children accessing emergency ambulances for non-emergency problems may be different to that of adults, particularly as calls are almost always made by a third party. Given the demands placed on overstretched ambulance resources, it is important to understand why parents and carers call 999 for their children with non-emergency problems. For the purposes of this review, ‘non-emergency’ problems refer to illnesses or circumstances where immediate treatment/intervention of a potentially life-threatening condition is not required, for example, calls that could be managed more appropriately in a primary care setting.

To our knowledge, there is no current systematic review exploring the drivers behind ambulance requests for children with non-emergency problems. Therefore, this review seeks to explore what is currently understood about the factors associated with ambulance use for non-emergency problems in children. The findings will be used to inform emerging interventions to more appropriately manage calls to the ambulance service for non-emergency problems in children.

Methods

We undertook a systematic mapping review and qualitative synthesis of published journal articles and relevant grey literature, exploring the question ‘What factors are associated with ambulance use for non-emergency problems in children?’ A systematic map is a review methodology often used in health services research that aims to ‘map out’ and categorise literature on a specific topic with an aim of this developing into more comprehensive work,8 and is often used in health services research.9 This methodology is particularly beneficial for summarising and organising a broad and varied evidence base, to identify a focus for more specific investigation.10

Search strategy

Searches were conducted on the following databases, for articles published between January 1980 and July 2020: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and AMED. A Google Scholar and a Web of Science search were undertaken to identify reports or proceedings not indexed in the above. Book chapters and theses were searched via the OpenSigle, EThOS and DART databases. A literature advisory group, including experts in the field, were contacted for relevant grey literature and unpublished reports. The database resources were selected, as they include the key medical databases. OpenGrey was used as the source for grey literature, as it covers the relevant subject areas for this review and has open access to over 700 000 bibliographical references. Search terms were developed iteratively by discussion among the research team and a librarian, seeking a balance between comprehensiveness and focus. A combination of MeSH terms and synonym text-strings/phrases was used in the search strategy, and these were combined using Boolean operators. The full review protocol and search strategy was published prospectively in the PROSPERO register. Update searches were rerun before final analysis, and again prior to submission.

Search terms

| Ambulance | Non-emergency | Children |

| Pre-hospital | Non-urgent | Child |

| Prehospital | Minor | Pediatric |

| Paramedic | Primary care | Paediatric |

| Out of Hospital | Non-serious | Baby |

| 999 | Low acuity | Babies |

| EMT | Routine | Infant |

| EMS | Schoolchild | |

| Emergency Medical Service | Adolescent | |

| Emergency Call | Teenager | |

| Young person | ||

| Parent | ||

| Mother | ||

| Father | ||

| Neonate |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria incorporated articles published in the English language between January 1980 and July 2020, reporting findings for the reasons behind why there are so many calls to the ambulance service for non-urgent problems in children. There were no restrictions on the types of study included in the systematic literature mapping stage of the review (phase A). Due to the minimal qualitative research available, all articles were screened to identify whether they were suitable to be included in the qualitative synthesis stage of the review (phase B). Studies were included if they had alluded to what was deemed as an ‘inappropriate’ or ‘appropriate’ call to the ambulance service. The ‘WHO’ definition of a ‘child’ was used for this review of international evidence: a child is defined as a person 19 years or younger unless national law defines a person to be an adult at an earlier age.11 The papers reviewed were limited to English-language studies, due to resource restrictions and the cost of translation. The systematic review included a wide range of primary research, to capture all relevant evidence. It was thought that limiting the search period to 1980 was likely to identify all, but a small minority of research completed before this time. Studies that reported purely on routine primary care or community care without any involvement of the ambulance service, or only on situations, illnesses or circumstances where immediate treatment/intervention of a potentially life-threatening condition was required, or studies that reported purely on attendance to the emergency department if there was no mention of the prehospital phase, were excluded.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Calls to the ambulance service | Studies that report purely on routine primary care or community care without any involvement of the ambulance service |

| Non-emergency problems | Studies that report purely situations, illnesses or circumstances where immediate treatment/intervention of a potentially life-threatening condition was required |

| A child under 19 years of age | A person older than 19 years of age |

| English-language studies | Studies that report purely on attendance to the emergency department if there is no mention of the prehospital phase |

| Primary quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods research | |

| Grey literature | |

| Date of publication 1980–present | |

| Studies were included if they had alluded to what was deemed as an ‘inappropriate’ or ‘appropriate’ call to the ambulance service (phase B) |

Extracting, coding, synthesising and analysing the data

Data extraction was divided into two stages:

Phase A: extraction of data to generate a broad systematic literature ‘map’.

Phase B: extraction of data from highly relevant papers using qualitative methods to undertake a focused qualitative synthesis.

A thematic synthesis was undertaken, following the approach described by Thomas and Harden.12 An initial table of themes associated with reasons for non-emergency calls to the ambulance service for children formed the ‘thematic map’ element (phase A). The ‘thematic mapping’ element was high level, due to the heterogeneity of the studies in setting, methodology and focus. The uniting feature running through all of the identified themes was the determination of ‘inappropriateness’ or ‘appropriateness’ of an ambulance call out, and this formed the specific concept of focus for the qualitative synthesis (phase B).

Owing to the inclusive nature of this review, and lack of relevant literature, it was decided to include findings from studies of all methodologies. First, standard author, background, methods, findings/conclusions and limitations were extracted and inserted into a table. Following this, key messages for the mapping stage (phase A) were extracted and included in the table. Verification was undertaken independently by other members of the research team and regular research meetings were held during the data extraction process; any disagreement was resolved by consensus discussion. For the qualitative synthesis (phase B), papers from phase A were screened, and reasons for inclusion or exclusion for this phase were also detailed in the table.

Phase A

In keeping with previously published work in this area,13 an inductive coding frame was developed to map emerging concepts. The key messages of all studies included at this stage (qualitative and quantitative) were extracted from the results/conclusions section, along with the methodology, where they were applicable to an ambulance service, and included non-emergency calls for children. After independently producing a series of pilot categories based on a sample of papers, the research team met to form consensus on category. Duplicate coding by another researcher took place on a sample of the papers, such that all the main themes were double coded. A summary literature map including the key themes was produced at this point.

Phase B

All papers deemed appropriate for the systematic mapping process (phase A) were deemed eligible for entry into the thematic synthesis stage (phase B). Of these, papers were screened for detail regarding how a call was deemed ‘inappropriate’ or ‘appropriate’, to identify eligibility. Due to a very limited number of qualitative journal articles, all methodologies were included. Working from a theoretical foundation of critical realism, a thematic synthesis of the qualitative literature was undertaken. This process was divided into the three stages described by Thomas and Harden12 : line-by-line textual coding, generation of descriptive themes and final formulation of analytical themes to take the understanding beyond the primary studies alone, and develop new interpretive constructs to provide greater understanding. Data from the results and discussion/conclusion sections of the included papers were individually coded. Each paper was then text-coded line by line, to generate a bank of translational codes. Papers were independently coded by members of the research team. Descriptive themes were generated for these translational codes and were verified among the researchers in the team, with any disagreement resolved by consensus discussion.

There are a range of methodological approaches to handling and analysing data extracted under the ‘phenomena on interest and context’ model as part of a qualitative synthesis. These include metatheoretical and metaethnographic approaches that draw on grounded theory and follow ‘lines-of-argument’ in the synthesis of ‘key concepts’, and critical interpretive methods resulting in synthetic constructs.14 While these approaches are most commonly applied to purely qualitative datasets, we draw on the evolving approach of an ‘integrated design’ of reviewing mixed-methods primary data (as opposed to the contrasting approaches of a sequential or cyclical design),15 16 whereby the methodological differences in qualitative and quantitative data are minimised, allowing them to be treated as producing findings that can be readily synthesised because they assess the same fundamental research question or purpose. By extracting and codifying the results and discussions sections of all our included studies, we treat the data at this level as ‘equivalent in purpose’ under this premise. Furthermore—and in keeping with concept of a ‘data-based convergent synthesis approach’,17 only one synthesis takes place with all included study designs—in our analysis, this is thematic.

Assessment of quality

Due to the inherent complexity in characterising ‘quality’ of the included studies, quality assessment was undertaken with the primary aim of informing the interpretation of the synthesis, rather than excluding studies on the grounds of quality alone. All relevant studies were included in phase A of the review without formal quality appraisal. Phase B used a modified version of the 10-point CASP tool. The CASP checklist is often used for quality assessment in qualitative syntheses, encouraging assessment of a paper against several items related to the purpose, design, conduct and reporting of qualitative research. The modified version of the CASP checklist used in this synthesis has been optimised by other authors specifically for quality appraisal as part of qualitative evidence synthesis.18 It includes prompts that help assess the paradigmatic congruence of included papers with their methods, methodologies and conceptual framework. This is in addition to the broader overall appropriateness of the qualitative methodology, credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, including detail of the reporting. No studies were excluded on assessment of quality grounds.

Patient and public involvement

Lack of resources prohibited the use of a designated patient and public group for this study. However, the research question was informed by engagement with members of the public and professionals in ongoing emergency care research.

Results

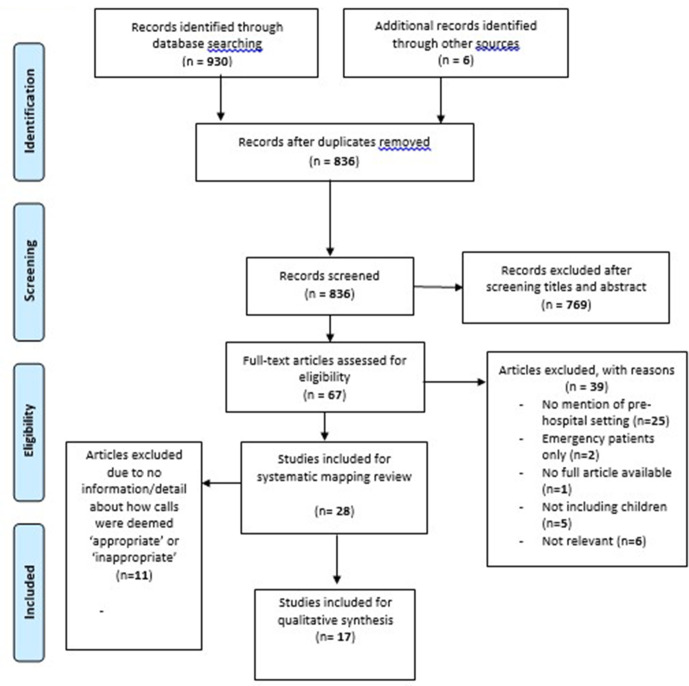

A total of 936 articles were identified in the initial searching process. After duplicates were removed, the total number of records screened was 836. After screening titles and abstracts, 769 articles were then excluded, which left 67 full-text articles to be assessed for eligibility by two members of the research team, independently. Of these, 39 articles were excluded for reasons including: no mention of the prehospital setting, included confirmed emergency patients only, no full article available, did not include children or was not relevant. Therefore, 27 articles were used in the systematic mapping review (phase A) (n=21 quantitative, n=2 mixed methods, n=2 qualitative and n=2 literature reviews).

The phase A papers were then read in detail to assess for any information regarding how the authors deemed calls to be ‘appropriate’ or ‘inappropriate’. Eleven articles were excluded, due to no reference to the concept of ‘appropriateness’, leaving 17 articles for the qualitative synthesis stage of the review (phase B) (n=13 quantitative, n=1 mixed methods, n=2 qualitative and n=1 literature review) (see figure 1, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart).19

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.19

Phase A: Systematic map: what factors are associated with ambulance use for non-emergency problems in children?

A summary of literature map including key themes was produced (box 1), followed by the development of categories (table 1).

Box 1. Key themes for reasons associated with non-urgent calls to the ambulance service for children.

1. Geographical area (urban areas associated with more calls for non-urgent presentations).

2. Lack of availability to be seen in primary care (both actual and perceived).

3. Uninsured patients (USA).

4. Infants (under 1 year).

5. Level of parental education (including status and medical knowledge).

6. Lower socioeconomic area.

7. Lack of understanding of the prehospital care system (unsure what qualifies for ‘appropriate’ ambulance call for their child).

8. Parent perceived emergency—fever.

9. No other means of transportation.

10. First-time parents.

11. Parental unemployment.

12. Schools.

13. Parental anxiety (particularly in higher socioeconomic areas).

14. Feeling of helplessness (particularly bystanders).

Table 1.

Categories of key themes

| Socioeconomic status/geographical | Practical reasons | Fear of consequences | Level of parental education |

| Geographical area—urban | Lack of availability to be seen in primary care | Infants under 1 year | Status, for example, no degree |

| Uninsured (USA) | No other means of transport | Schools | Lack of understanding of the prehospital care system |

| Lower socioeconomic area | Parental anxiety (higher socioeconomic area) | ||

| Parental unemployment | Feeling of helplessness | Perceived emergency | |

| First-time parents |

Socioeconomic status and geographical location

Several studies have found a significant link between location and non-emergency calls to the ambulance for children; in particular, urban areas were associated with more ambulance use.3 20 One study assessing the ‘appropriateness’ of ambulance use in paediatrics presenting to the emergency department (ED) identified a higher rate of what the authors termed as ‘misuse’ of ambulances for children in urban populations, and suggested that suburban parents would be less likely to call the ambulance ‘inappropriately’. The authors wrote that suburban locations have lower rates of ‘misuse’, since they are accustomed to coming to the hospital via private vehicle.21

One North American retrospective study found that parents with children in areas with lower income used EMS more frequently, and repetitively (11% called the ambulance more than once in the 3 years). The authors reported a significant linear relationship between transport rate and family income by postcode.22 In a German study, medium socioeconomic status was associated with the lowest percentage of non-emergency calls to the ambulance service for children. There were several ‘inappropriate’ calls due to what the authors described as ‘overanxiety’ of parents in high socioeconomic areas, however this was still not as many as in the lower socioeconomic areas.23 Salmi et al24 aimed to explore whether the socioeconomic status of a neighbourhood could predict the incidence of paediatric out-of-hospital emergencies in Finland, and concluded that poorer neighbourhoods significantly increased ambulance use for children.

Several studies reported that Medicaid patients account for the majority of non-emergency calls to the ambulance for children; 43% of patients were insured by Medicaid, (the US federal and state programme that helps with medical costs for people with limited income) and 60% of what the authors termed as ‘unnecessary’ calls were to those without commercial insurance.21 Further studies also concluded that non-insured paediatric patients had significantly higher rates of ambulance use compared with those who were privately insured.20 23 25

Level of parental education

The most common presenting report for ‘inappropriate’ ambulance use in children was fever; nearly half of the calls for fever in children were deemed non-emergency and an unnecessary use of the ambulance.21 Ninety-two per cent of children who were conveyed via ambulance to the ED with these symptoms were discharged home with no intervention.26 The authors concluded that parents overestimate the seriousness of fever, and that parents are often unsure as to what qualifies as an emergency requiring an ambulance for their children.27

A prospective single-centre cohort study conducted in Germany aimed to provide current data on the ‘inappropriate’ use of ambulances for children and explore the reasons why. The main factor was parental perceived emergency, particularly with first-time parents,23 which was a common finding in other studies.28 A lower paternal and maternal educational status resulted in significantly more EMS use. Speculatively, the authors suggest that parents with low income have poorer medical knowledge and this is associated with ‘inappropriate’ use of ambulances: ‘A lack of basic medical knowledge and experience in the proper assessment of children appears to be a contributing factor to inappropriate ambulance use for non-urgent problems’. Lower parental education or ‘inadequate parental health literacy’, as the authors write, seems to be associated with more calls internationally, and of these calls, more are low acuity.24

Practical reasons

Shah et al3 identified a link between increased EMS use for non-emergency problems in children if there was limited availability in primary care health services. Similarly, Sinclair29 found there was an increase in ambulance use due to lack of access to primary care physicians in the community, and lack of community support for children.

A common reason identified in the studies for parents calling an ambulance for non-emergency problems is lack of transport to take their child to the ED.30 31 This was particularly the case for single parents.2 Kost and Arruda21 report that parents admitted that they called the ambulance if there was no other means of transportation or if they had other childcare considerations; ‘they would have used a taxi or shuttle if they could’. Similarly, one study found that often parents knew that an ambulance was not required, however 40% of parents stated they had no other means of transportation.32 A descriptive survey study found that parents will call the ambulance for convenience as well as perceived need.33 Additionally, one study found that parents believe that they will be seen faster in ED if they arrive there via ambulance.2

Fear of consequences

Parents’ and caregivers’ fear of doing the wrong thing ethically and morally, being advised by other healthcare professionals to follow a certain course of action (eg, ambulance) even if they felt it clinically unnecessary, reduced confidence in their own judgement, and not wanting to take any risks were all common reasons for calling the ambulance for non-urgent problems in children.2 One study found that parents of infants (under 1 year) are more likely to use the ambulance service22 and that parents often overestimate their child’s illness.32 Eastwood et al34 completed a descriptive epidemiological review in Australia, which showed that often parents call the ambulance for reassurance. As far as schools are concerned, the majority of ambulance transport is unjustified; however, schools call for emergency services due to fear of consequences, which poses an area of potential relief for the ambulance service which is already stretched to its limits.28 Heightened anxiety due to previous experiences of traumatic events also resulted in ‘inappropriate’ calls to the ambulance.2

Phase B: Qualitative synthesis: how are calls to the ambulance service for children deemed ‘inappropriate’?

A total of 15 descriptive themes were developed iteratively by repeated rounds of inductive grouping of codes, until no additional discrete codes were needed to fully describe the dataset (box 2). Through a process informed by the principles of charting, these descriptive themes were then organised and condensed into seven related (ie, not mutually exclusive) descriptive thematic groups, by considering the axis of the descriptive themes (box 3). By analysing patterns in the free codes and descriptive themes within and across the seven thematic groups, a number of cross-relationships between groups were identified. Through a process of comparing the theme groups and their constituent descriptive themes, three overarching analytical themes were identified and discussed below (box 4).

Box 2. Descriptive themes related to how calls to the ambulance for non-urgent problems in children have been deemed inappropriate.

1. Calls are deemed ‘appropriate’ by ED doctors using predetermined criteria from a Delphi study, such as: requiring CPR, respiratory distress, seizure, altered mental status, unable to walk, admitted to ICU, ambulance called by GP, RTA, parents not available to transport.

2. ‘Inappropriate’ if the main reason for the call was due to lack of transport.

3. ‘Inappropriate’ if there has been no intervention/investigation/treatment in ED or by paramedics.

4. Appropriateness determined using the Emergency Severity Index.

5. Classed as ‘inappropriate’ if not an acute onset of symptoms.

6. Determined by ED doctors with varying levels of qualification—the more experience the clinician, the more they thought calls were ‘inappropriate’.

7. Parental perception of ‘non-life threatening’ associated with ‘inappropriate’ calls.

8. ‘Inappropriate’ calls associated with not calling the GP first (if patients have tried this and exhausted alternative options than can be deemed as more appropriate).

9. Appropriateness was often based on vital signs.

10. Deemed ‘inappropriate’ if assigned ‘non-urgent’ at triage in ED.

11. Deemed ‘inappropriate’ if could be managed more suitably in primary care.

12. Australian Triage Score (if scores 4 or 5 then deemed non-urgent and inappropriate use).

13. Deemed as non-urgent if it was safe to use alternative transport.

14. Deemed non-urgent if the condition is unlikely to deteriorate or require admission/surgery.

15. ‘Appropriate’ if ‘lights and sirens’ are used.

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner; ICU, intensive care unit; RTA, road traffic accident.

Box 3. Thematic groups of how calls were determined to be ‘inappropriate’.

Determined by clinicians.

Determined retrospectively.

Determined on the level of acuity.

Determined using a scoring system.

Determined because of practical reasons, such as no transport and not contacting the general practitioner (GP).

Determined because the problem would be more suitably managed in primary care.

Determined because of speaking to a GP first.

Box 4. Analytical themes.

Practicalities and logistics of obtaining care.

Arbitrary scoring system.

Retrospection.

The practicalities and logistics of obtaining care domain contains descriptive themes relating to the practical reasons for determining ‘inappropriate’ use of an ambulance, including themes associated with convenience, access issues and transport. The arbitrary scoring system domain brings together descriptive themes concerning the use of scoring tools to determine whether a call to the ambulance is ‘inappropriate’ or not. The retrospection domain refers to the descriptive themes relating to calls being deemed as ‘inappropriate’ retrospectively by clinicians, for example, after vital signs have been taken.

Practicalities and logistics of obtaining care

Many of the themes identified that calls were considered to be ‘inappropriate’ because of practical aspects, logistical difficulties and convenience. In one study, parents and caregivers had called an ambulance solely due to having no other means of transportation, this was deemed as an ‘inappropriate’ use of the ambulance service.32 The authors identified that 40% of parents admitted to calling the ambulance due to having no transport, and of those 80% were considered’ inappropriate’. Other studies determined’ inappropriate’ ambulance use if it was safe to use alternative transport.30 31 35

Several studies suggested that parents and caregivers use ambulances for convenience and this is ‘inappropriate’,32 particularly if the report could be suitably managed in primary care.36 Parental perception of the situation as non-life threatening was associated with ‘inappropriate’ use of the ambulance service, where parents and caregivers actually expressed that ambulance transportation is more convenient, if not strictly a necessity at times.23 ‘Inappropriate’ use of ambulances was associated with parents and caregivers not calling a general practitioner (GP) first when indicated (non-life-threatening medical need),23 and when they sought advice from a GP first, the use of emergency services was considered more ‘appropriate’.27 Equally, calls to the ambulance for children were deemed ‘appropriate’ if patients had tried to access their GP, but that system has failed them.31

Arbitrary scoring system

Several studies sought to determine ‘inappropriateness’ using semiobjective arbitrary scoring or coding systems. Kost and Arruda21 analysed records retrospectively and deemed ambulance transport unnecessary unless the medical record included any of the following criteria: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, respiratory distress, immobilisation, inability to walk, admission to intensive care unit, ambulance recommended by medical personnel, road traffic collision or parents not on scene. The authors considered these criteria to be more liberal than others. In Bober et al20 study, accident and emergency doctors considered 61% of paediatric arrivals by ambulance as ‘unnecessary’. The doctors determined ‘appropriateness’ using the Emergency Severity Index levels (a validated triage tool used in the ED), which has been used in other studies.37 Similarly, calls to the ambulance have been thought of as ‘inappropriate’ if they were deemed as non-emergency at triage in the ED.32 Other tools used to determine ‘appropriateness’ is the Australian Triage Score33; if children scored 4 or 5 (non-urgent), then the call was thought to be’ ‘inappropriate’.

Retrospection

The majority of studies sought to determine ‘inappropriateness’ retrospectively, normally by a variety of different clinicians. This is an important consideration, as this suggests that the call can only be deemed ‘inappropriate’ after the consultation process and diagnosis. In a German study, calls were determined to be an ‘inadequate’ or ‘adequate’ use of the ambulance service by three doctors of different seniority.23 Interestingly, there were significant differences in what the three doctors considered to be inappropriate’ calls to the ambulance service and this was dependent on experience; the more experienced doctor reported more calls to be ‘inappropriate’. Similarly, ‘appropriate’ use of the ambulance service in one study was determined by a doctor, based primarily on chief report, general appearance, vital signs and ambulance patient report forms, which concluded that 61% of ambulance calls to children were ‘inappropriate’.32 A US study involving children used medical necessity criteria agreed at a consensus conference, to make an assessment on ‘appropriateness’, and concluded that 16.4% of all transports were an unnecessary use of the ambulance.25

A qualitative study interviewing paramedics on what they considered to be the ‘appropriate’ use of the ambulance service concluded that a call is ‘appropriate’ if it needed ‘lights and sirens’ to hospital and was of a ‘life threatening’ nature.31 Calls were considered’ inappropriate’ if there had been no ambulance intervention,21 unless the child was under 2 years old,38 or if there was not an acute onset of symptoms.23 It is clear that ‘fever’ as a presenting report is considered the most ‘inappropriate’ use of ambulances for children by clinicians according to the literature.35

Discussion

This systematic review involved a two-stage process exploring which factors are associated with ambulance use for non-emergency problems in children, and how ‘inappropriateness’ in non-urgent ambulance use in children has been determined. The reasons for parents and caregivers calling 999 for their children with non-emergency conditions are complex and multifaceted. This review reveals an intricate relationship between the urgency of the clinical problem and the ‘appropriateness’ of ambulance service use. To our knowledge, there is no review exploring the factors associated with non-emergency ambulance use in children. An important consideration across the identified factors, which was illustrated by the systematic map (phase A) was how to determine ‘appropriateness’ or not. Undertaking a thematic synthesis enabled the research team to go beyond the individual frameworks that each paper had used to determine this, and combined to the knowledge to identify gain understanding on the ‘concept’ of ‘inappropriateness’ in non-emergency ambulance use in children.

Systematic map

Previous work examines how help seeking may apply to some urgent care settings, such as EDs.39 40 It is apparent that some parents will bring their child to the ED for non-urgent care, due to perceived difficulties with contacting their GP, and the presumed advantages of ED care. Findings from this review also suggest that parents call the ambulance for non-emergency problems due to perceived barriers for accessing their GP, and speed of access. The studies in the review suggested that perceived problems with primary healthcare services were affecting parents’ and caregivers’ use of the ED and ambulance services for minor illness. Convenience was also a reason highlighted in the studies for parents attending the ED.41 Perceived urgency was a main theme identified in this study and is also the most frequently cited reason for visiting the ED by parents of children presenting with non-urgent issues.41 Often, parents felt that their child’s condition constituted a genuine emergency, but did not necessarily require an ambulance, which was called due to lack of transportation. First-time parents and children under 1 year were common reasons for non-emergency calls to the ambulance service, which aligns with other studies on presentation at EDs, which was increased among parents of newborns and first-time parents.42

Aligning with previous studies focused on adults, our findings show that increased ambulance use for non-urgent problems in children is conceptually associated with lower socioeconomical urban locations.43 In addition, this review identified that children being uninsured (US studies) was an associating factor for non-emergency ambulance use, which has also been reported in previous studies of adults.25 Another common motivator is lack of transport, which is a factor also identified in the non-emergency use of ambulance services with adults.44 The sociodemographic factors of rurality, deprivation and education may warrant further investigation to understand the underlying factors behind this increased use.

The most common presenting report associated with non-emergency calls to the ambulance service for children was fever.26 This suggests an area of parental education that could be improved in order to reduce non-emergency calls to the ambulance service, and may have implications to how calls are triaged. This is reported in other studies suggesting that focusing educational efforts in regard to ‘appropriate’ ambulance use on the adolescent population will likely reduce ‘inappropriate’ ambulance use in the paediatric population.20 Additionally, further exploration at the ambulance triage and dispatch stage for children may be beneficial.20 Fear of the consequences among parents and caregivers where children are concerned is a clear factor in increased ambulance use; however, parental concern could be a legitimate triage discriminator. Recurring messages in other literature also portray patient and carer uncertainty around urgency, the fear of harm if treatment is delayed and the value placed on clinical assessment for reassurance.45 The findings of this review indicate that parents and carers often do not know exactly what type of help they need when they contact urgent care services, or what constitutes a need for an emergency ambulance for their child.23 Providing parents with the knowledge about what constitutes emergency and non-emergency care for typical infantile diseases could help with parents’ decision-making.

Qualitative synthesis

The assessment of ‘inappropriateness’ of an ambulance contact is multifaceted and diverse in the evidence, which is a result of methodological limitations and conceptual variation. According to the evidence, ‘inappropriate’ use of the ambulance service for children is at a similarly high level to that of the adult population.21 The majority of studies sought to determine ‘inappropriateness’ retrospectively, using semiobjective (yet arbitrary) scoring systems, and almost universally determined by clinicians following an assessment that included recording of vital signs.46 However, the assessment of ‘appropriateness’ based on information obtainable after clinical assessment will likely overestimate ‘inappropriate’ use, and disregard the multifaceted psychosocial context of the demand for help, which is even greater when concerning children. Authors have suggested that there is not enough information in the ‘diagnostic label’ alone to judge whether a call is ‘appropriate’ or not.5

Clearly, one of the issues with deeming a call to be ‘inappropriate’ is how this is classified differently by professionals, compared with the lay public.4 The higher the acuity, the greater it seems to be considered as ‘appropriate’ by clinicians. However, there are no hard and fast criteria; for example, ‘those needing lights and sirens’ is still a personal judgement. It seems that if a clinician thinks it is an urgent call, then it is ‘appropriate’ but what is urgent to a clinician can be different to the general public. Indeed, as reflected in the findings from the current study, previous literature suggests differences between clinician classifications of emergency (based on physiological measures) are in contrast with patient-based determinations of emergency (often defined by practical factors or fear of consequences).

There is suggestion that calls are ‘inappropriate’ if there is no ambulance intervention, however this is arguable because patients often benefit from rapid transportation, particularly children.21 Calls were deemed as ‘inappropriate’ if other transport options or other services were available and more suitable.30 In other work, studies have shown that patients and carers ‘weigh up’ how practical the use of the ambulance service (or alternatives) are for their perceived needs, and sometimes patients genuinely expect the ambulance service to treat minor ailments.7 This shows a lack of public and caregiver understanding about the use of ambulances for paediatrics.

Limitations

The heterogeneity of study methodologies presents a challenge in drawing together associated and conflicting findings. There is little evidence available addressing the specific question, reflected in the small number of studies suitable to the review criteria. Because of the limited evidence, the analysis is limited in areas. Much of the data is retrospective and therefore often incomplete and not recorded accurately. All included studies in this review were carried out in wealthy countries. It is likely that many of the issues will remain the same for low-income countries, however some will be unique given the variability in cultural, economic and political contexts. By limiting our searches to the English language, we may have inadvertently excluded important sources.

Conclusion and future research

There is a lack of public and caregiver understanding about the use of ambulances for paediatrics. There are some factors that appear specific to choosing ambulance care for children that are not so prominent in adults (fever, reassurance, fear of consequences) and there are some ways in which ‘appropriateness’ might be looked at differently for children and adults. Further primary, qualitative research is required to explore parents, caregivers, teachers and young teenagers’ reasons for calling the ambulance for non-emergency problems in children. Providing alternate means of transportation, strategies for helping caregivers to mitigate perceived risk, increasing the perception and reality of access to urgent primary care or targeted education to certain residential areas and first-time parents with infants (particularly regarding fever) may decrease unnecessary ambulance activation for paediatric low-acuity reports. Most studies included were conducted in high-income countries, subsequently there is a need for further investigation among low-income countries, which may provide important and unique insights. Future interventions could be designed to impact parents’ decision-making prior to calling an ambulance for their child. Both policymakers and academics need to work towards a contextually nuanced and consistent definition of ‘appropriate’ ambulance resource use.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @MatthewBooker

Contributors: MJB developed the original idea and supervised the work. AP conducted the review and took a lead on writing the manuscript. All authors interpreted and analysed the results. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. HB finalised the approval of the version to be published.

Funding: MJB is funded by an NIHR Clinical Lecturer Post.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.England NHS. High quality care for all, now and for future generations: transforming urgent and emergency care services in England, 2013. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/urg-emerg-care-ev-bse.pdf [Accessed 30 Jul 2020].

- 2.O’Cathain A, Connel J, Long J. ‘Clinically unnecessary’ use of emergency and urgent care: a realist review of patients' decision making. Health Expect 2020;23. 10.1111/hex.12995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah MN, Cushman JT, Davis CO, Davis JB, et al. The epidemiology of emergency medical services use by children: an analysis of the National hospital ambulatory medical care survey. Prehosp Emerg Care 2008;12:269–76. 10.1080/10903120802100167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgans A, Burgess SJ. What is a health emergency? the difference in definition and understanding between patients and health professionals. Aust Health Rev 2011;35:284–9. 10.1071/AH10922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snooks H, Wrigley H, George S, et al. Appropriateness of use of emergency ambulances. J Accid Emerg Med 1998;15:212–8. 10.1136/emj.15.4.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durand A-C, Palazzolo S, Tanti-Hardouin N, Hardouin NT, et al. Nonurgent patients in emergency departments: rational or irresponsible consumers? perceptions of professionals and patients. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:525. 10.1186/1756-0500-5-525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Booker MJ, Purdy S, Shaw ARG. Seeking ambulance treatment for 'primary care' problems: a qualitative systematic review of patient, carer and professional perspectives. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016832. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009;26:91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakley A, Gough D, Oliver S, et al. The politics of evidence and methodology: lessons from the eppi-centre. Evid Policy 2005;1:5–32. 10.1332/1744264052703168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. Synthesizing qualitative and quantitative health evidence: a guide to methods. Berkshire, England: Open University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organisation . Definition of key terms, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/intro/keyterms/en/ [Accessed 02 Aug 2020].

- 12.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:671–84. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00064-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.pp. Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:35–47. 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Res Sch 2006;13:29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. Using mixed-methods research synthesis for literature reviews. New York: Sage Publications, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, et al. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev 2017;6:61. 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (casp) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Rese Metho Med & Health 2020;1:31–42. 10.1177/2632084320947559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bober J, Stefanov D, Paladino L. The role of health insurance in paediatric ambulance use: are children just small adults? Open Access Text 2017. 10.15761/TEC.1000125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kost S, Arruda J. Appropriateness of ambulance transportation to a suburban pediatric emergency department. Prehospital Emergency Care 1999;3:187–90. 10.1080/10903129908958934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller MK, Denise Dowd M, Gratton MC, et al. Pediatric out-of-hospital emergency medical services utilization in Kansas City, Missouri. Academic Emergency Medicine 2009;16:526–31. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poryo M, Burger M, Wagenpfeil S, et al. Assessment of inadequate use of pediatric emergency medical transport services: the pediatric emergency and ambulance critical evaluation (peace) study. Front Pediatr 2019;7. 10.3389/fped.2019.00442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salmi H, Kuisma M, Rahiala E, et al. Children in disadvantaged neighbourhoods have more out-of-hospital emergencies: a population-based study. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:archdischild-2017-314153. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson PD, Baxley EG, Probst JC, et al. Medically unnecessary emergency medical services (EMS) transports among children ages 0 to 17 years. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:527–36. 10.1007/s10995-006-0127-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fessler SJ, Simon HK, Yancey AH, et al. How well do general EMS 911 dispatch protocols predict ED resource utilization for pediatric patients? Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:199–202. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watts J, Cowden JD, Cupertino AP, et al. 911 (nueve once): Spanish-speaking parents' perspectives on prehospital emergency care for children. J Immigr Minor Health 2011;13:526–32. 10.1007/s10903-010-9422-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson D, Heinz P. G27(P) paediatric emergency ambulance transport: who calls 999 and why. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:A12–13. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306237.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinclair D. Emergency department overcrowding - implications for paediatric emergency medicine. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12:491–4. 10.1093/pch/12.6.491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Champagne-Langabeer T, Langabeer JR, Roberts KE, et al. Telehealth impact on primary care related ambulance transports. Prehosp Emerg Care 2019;23:712–7. 10.1080/10903127.2019.1568650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dejean D, Giacomini M, Welsford M, et al. Inappropriate ambulance use: a qualitative study of Paramedics' views. Healthc Policy 2016;11:67–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camasso-Richardson K, Wilde JA, Petrack EM. Medically unnecessary pediatric ambulance transports: a medical taxi service? Academic Emergency Medicine 1997;4:1137–41. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unwin M, Kinsman L, Rigby S. Why are we waiting? patients' perspectives for accessing emergency department services with non-urgent complaints. Int Emerg Nurs 2016;29:3–8. 10.1016/j.ienj.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eastwood K, Morgans A, Smith K, et al. A novel approach for managing the growing demand for ambulance services by low-acuity patients. Aust Health Rev 2016;40:378–84. 10.1071/AH15134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards ME, Hubble MW, Zwehl-Burke S. "Inappropriate" pediatric emergency medical services utilization redefined. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011;27:514–8. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31821c98bf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sprivulis P, Grainger S, Nagree Y. Ambulance diversion is not associated with low acuity patients attending Perth metropolitan emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas 2005;17:11–15. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2005.00686.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gregory EF, Chamberlain JM, Teach SJ, et al. Geographic variation in the use of low-acuity pediatric emergency medical services. Pediatr Emerg Care 2017;33:73–9. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blundell K, Abrahamson E. G106(P) inappropriate ambulance use in paediatrics. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:A45.3–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308599.105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langer S, Chew-Graham C, Hunter C, et al. Why do patients with long-term conditions use unscheduled care? A qualitative literature review. Health Soc Care Community 2013;21:339–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01093.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berry A, Brousseau D, Brotanek JM, et al. Why do parents bring children to the emergency department for non-urgent conditions? a qualitative study. Ambulatory Pediatrics 2008;8:360–7. 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.pp. Butun A, Linden M, Lynn F, et al. Exploring parents’ reasons for attending the emergency department for children with minor illnesses: a mixed methods systematic review. Emerg Med J 2018:emermed-2017-207118–8. 10.1136/emermed-2017-207118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fieldston E, S, Alpern ER, Nadel FM. A qualitative assessment of reasons for non-urgent visits to the emergency department: parent and health professional opinions. Paediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:220–5. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318248b431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rucker DW, Edwards RA, Burstin HR, et al. Patient-specific predictors of ambulance use. Ann Emerg Med 1997;29:484–91. 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70221-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawakami C, Ohshige K, Kubota K, et al. Influence of socioeconomic factors on medically unnecessary ambulance calls. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:120. 10.1186/1472-6963-7-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahl C, Nyström M, Jansson L. Making up one's mind:--patients' experiences of calling an ambulance. Accid Emerg Nurs 2006;14:11–19. 10.1016/j.aaen.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durant E, Fahimi J. Factors associated with ambulance use among patients with low-acuity conditions. Prehosp Emerg Care 2012;16:329–37. 10.3109/10903127.2012.670688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.