Abstract

Objectives:

Patients with prior irradiated head and neck cancer (HNC) who are ineligible for definitive retreatment have limited local palliative options. We report the largest series of the use of the Quad Shot (QS) regimen as a last-line local palliative therapy.

Materials and Methods:

We identified 166 patients with prior HN radiation therapy (RT) treated with QS regimen (3.7Gy twice daily over 2 consecutive days at 4 weeks intervals per cycle, up to 4 cycles). Palliative response defined by symptom(s) relief or radiographic tumor reduction, locoregional progression free survival (LPFS), overall survival (OS) and radiation-related toxicity were assessed.

Results:

Median age was 66 years. Median follow-up for all patients was 6.0 months and 9.7 months for living patients. Overall palliative response rate was 66% and symptoms improved in 60% of all patients. Predictors of palliative response were > 2 year interval from prior RT and 3–4 QS cycles. Median LPFS was 5.1 months with 1-year LPFS 17.7%, and median OS was 6.4 months with 1-year OS 25.3%. On multivariate analysis, proton RT, KPS>70, presence of palliative response and 3–4 QS cycles were associated with improved LPFS and improved OS. The overall Grade 3 toxicity rate was 10.8% (n=18). No Grade 4–5 toxicities were observed.

Conclusion:

Palliative QS is an effective last-line local therapy with minimal toxicity in patients with previously irradiated HNC. The administration of 3–4 QS cycles predicts palliative response, improved PFS, and improved OS. KPS>70 and proton therapy are associated with survival improvements.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, palliative radiation, reirradiation, Quad Shot, proton radiation therapy

INTRODUCTION

Relapse in the previously radiated head and neck presents a similar major challenge for radiation oncology, medical oncology, and head and neck surgery. Head and neck (HN) cancer patients with uncontrolled local recurrence(s) often present with very morbid symptoms (bleeding, wound, dysphagia, pain) and significant late toxicities (fibrosis, necrosis) that may limit possible interventions. Historically, factors like performance status, extent of disease, prior radiation therapy (RT) dose, and time interval from prior RT have been used to help guide the decision to offer definitive reirradiation (re-RT). The RTOG completed two Phase II studies of definitive re-RT in recurrent HN squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with median survival times of 8.5 months and 12.1 months.1,2 A Phase III trial of re-RT with or without chemotherapy was attempted but closed due to poor accrual. The MIRI Collaborative also provided guidelines on patient selection for definitive re-RT.3 However, these are typically targeted for those who are able to undergo definitive re-RT. For patients who are not able to complete a full re-RT course but suffer tremendous morbidity and imminent mortality, limited palliative options exist.

Multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic disease can achieve response rates around 35% with a median survival of 7.3 months.4 Specifically in the recurrent/metastatic setting, the addition of cetuximab to platinum-based chemotherapy has been shown to improve median survival from 7.4 to 10.1 months and increase the response rate from 20% to 36%.5 There has also been great enthusiasm for immunotherapy, with CheckMate141 reporting a median survival of 7.5 months with nivolumab versus 5.1 months with standard single-agent systemic therapy in HN SCC patients who progressed within six months of platinum-based chemotherapy; however, the response rate was only 13.3%.6 Similarly, KEYNOTE-040 reported that pembrolizumab improves median survival (8.4 versus 6.9 months) with less toxicity than standard of care chemotherapy in patients with recurrence after platinum-containing therapy; but response rates were only approximately 15%.7 The KEYNOTE-048 trial (NCT02358031) concluded that pembrolizumab and pembrolizumab/chemotherapy should be new first-line standards of care for patients with recurrent/metastatic HNSCC, but only demonstrated improved OS in patients with PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) of ≥ 20 and ≥ 1.8 Although systemic therapy can provide a survival benefit, overall response rates are low and the problem of local palliation can remain unaddressed for many. Additionally, for patients who are not candidates for immunotherapy or progress after systemic therapy, palliative re-irradiation can be an alternative option.

Given the generally dismal outcomes and importance of treatment efficiency for such frail and symptomatic patients, a variety of hypofractionated fractionation schemes have been successfully employed in palliative setting (ranging from 2.5–8 Gy per fraction, to total doses of 14–70Gy).9–17 Studies have reported that the Quad Shot (QS) regimen (3.7 Gy twice daily over 2 consecutive days at 4 weeks intervals per cycle, for up to 4 cycles) may offer the best balance between palliation, toxicity, and convenience.9,18–21 Our prior studies have shown that QS RT with either photon or proton therapy achieves excellent palliative responses (65–73%) and median survival in the 5.7–9.0 month range with minimal toxicity.22,23 As a consequence, the QS regimen became our institutional standard for last-line local therapy in the most formidable of this incurable subset of patients (those with local progression after prior RT and no other viable palliative options).

We present an updated and expanded report of our institutional experience with QS as a last-line local therapy in the incurable re-RT setting. To our knowledge, this is the first study simultaneously reporting outcomes with both photon and proton QS in patients with previously irradiated HNC.

METHODS

Patients

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, our institutional database and RT records from January 2011 to December 2018 were reviewed to identify 166 consecutive patients with recurrent or secondary primary HNC originating in a previously irradiated field, who were treated with at least one cycle of QS re-RT.

Patients were deemed ineligible for definitive local therapy by multidisciplinary consensus due to incurable advanced local recurrence(s), metastatic disease, poor performance status, or significant medical comorbidities. Further, 74 patients were treated with proton QS due to tumor location and complex local RT history.

Radiotherapy details and technique

Before each QS cycle, patients were simulated with computed tomography (CT) and immobilized in a thermoplastic five-point HN mask. The fusion of Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and CT simulation scan were used if available. The gross tumor volume (GTV) was defined by symptoms, clinical exam, or radiographically through available diagnostic imaging. The planning target volume (PTV) was created with a 0.3–0.5cm margin depending on setup uncertainty and available image-guidance during treatment. As all patients had prior HN RT, the spinal cord and brainstem were constrained to a guideline of maximum point dose of 60 Gy in 2 Gy equivalents from all treatments, with 70 Gy as the maximum allowable limit. Proton RT was delivered by uniform scanning proton beams with beam-specific apertures and compensators.

Treatment was prescribed 3.7 Gy twice daily, administered over two consecutive days to a total of 14.8 Gy per cycle. For proton patients, the prescription was for 3.7 Gy relative biological effectiveness (RBE) per fraction, assuming an RBE value of 1.1. In the absence of local disease progression or significant acute toxicity, each cycle was repeated at 4 weeks intervals. An additional 1–4 week break was used between QS cycles as needed for toxicity or other concerns. Before each QS cycle, treatment volumes were reviewed and reduced as needed for significant tumor response. At the discretion of radiation oncologists and medical oncologists, systemic treatments including cytotoxic chemotherapy, targeted agents and immunotherapy were delivered in patients with extensive or metastatic disease.

Outcomes and definitions

Palliative response was defined as subjective relief of presenting symptom(s) or objective reduction of the gross tumor volume on radiographic examination (complete or partial response). Objective tumor response was evaluated in 4 to 12 weeks after the last cycle of QS by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor (version 1.1) and positron emission tomography response criteria in solid tumors.24,25 Locoregional progression-free survival (LPFS) was calculated from the start of QS RT until the date of in-field tumor progression or death. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the start date of QS RT until date of death or last follow-up. Toxicity events were scored by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Statistical methods

Comparisons between cohorts were performed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test or Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables where appropriate. The correlation between palliative response and clinical factors was estimated by Spearman’s rho test. LPFS and OS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Prognostic factors were analyzed by Cox proportional hazards modeling.

RESULTS

Patients and treatment characteristics

Cohort descriptive characteristics are in Table 1. The median age was 66 years (range 22–101 years) and 72% were male. The most common histology was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, 78%), followed by salivary gland carcinoma (9%) and thyroid carcinoma (3%). The oral cavity was the predominant primary site of disease (32%), followed by oropharynx (18%). The majority (75%) had recurrence more than once and 43% of patients had organ dysfunction (tracheostomy and/or feeding tube due to cancer-related symptoms) at the time of QS. More than half of patients (59%) had KPS ≤70, and one-third of all patients had metastatic disease.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics

| Parameters | n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age at QS, median (range), y | 66 (22–101) |

| Previous RT dose, median (IQR), Gy | 70 (64–81) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 120 (72.3) |

| Female | 46 (27.7) |

| KPS | |

| < 70 | 98 (59.0) |

| > 70 | 68 (41.0) |

| Histology | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 129 (77.7) |

| Salivary gland | 15 (9.0) |

| Thyroid | 5 (3.0) |

| Other | 17 (10.2) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Oral cavity | 53 (31.9) |

| Oropharynx | 29 (17.5) |

| Larynx/hypopharynx | 17 (10.2) |

| Nasal cavity/paranasal sinus/nasopharynx | 21 (12.7) |

| Skin | 25 (15.1) |

| Others | 21 (12.7) |

| QS site | |

| Primary | 116 (69.9) |

| Neck | 34 (20.5) |

| Both | 16 (9.6) |

| Metastatic disease at time of QS | |

| Yes | 56 (33.7) |

| No | 110 (66.3) |

| Surgery for primary disease | |

| Yes | 128 (77.1) |

| No | 38 (22.9) |

| Salvage surgery prior to QS | |

| Yes | 15 (9.0) |

| No | 151 (91.0) |

| Systemic treatment prior to QS | |

| Yes | 126 (75.9) |

| 2 or more prior courses | 80 (48.2) |

| Recurrence more than once | |

| Yes | 124 (74.7) |

| No | 42 (25.3) |

| Previous RT course | |

| Once | 122 (73.5) |

| > once | 44 (26.5) |

| Interval time > 2 years from prior RT | |

| Yes | 62 (37.3) |

| No | 104 (62.7) |

| Organ dysfunction at time of QS | |

| Yes | 71 (42.8) |

| No | 95 (57.2) |

| QS radiation technique | |

| Photon | 92 (55.4) |

| Proton | 74 (54.6) |

| Concurrent systemic treatment with QS | |

| Yes | 83 (50.0) |

| No | 83 (50.0) |

| Cycles of QS | |

| 1 | 40 (24.1) |

| 2 | 41 (24.7) |

| 3 | 45 (27.1) |

| 4 | 40 (24.1) |

All patients had previously received HN RT with median dose of 70Gy (IQR 64–81). The majority (63%, n=104) had been radiated less than 2 years before QS, with median time between initial RT and QS of 15.0 months (IQR 8.3–38.5). Of note, 44 patients had received two or more prior courses of head and neck RT, and 61% of these patients were treated with proton RT. Approximately 77% of patients received surgical resection(s) for primary disease at any time during their treatment courses. Of the 128 patients with prior surgical resection(s), 78 (61%) underwent multiple surgical interventions, and 10 (9%) received more than 5 resections. A total of fifteen (9%) patients had salvage surgery prior to QS. Majority of patients (76%) received systemic therapy before the start of QS. Among these patients, 80 (63%) failed to multiple lines of regimens, and 7 patients failed to more than 5 courses of systemic treatments.

Ninety-two patients (55%) were treated with photons and 74 patients (45%) received proton RT. About half of patients (51%) were able to complete at least three cycles of Quad Shot. Based on a variety of factors including performance status and the presence of metastatic disease, concurrent systemic treatment was administered at the discretion of the treating medical oncologist in half of patients. Among these patients, 30 (36%) patients received chemotherapy, 32 (39%) patients received cetuximab, 11 (13%) patients received immunotherapy, and 10 (12%) patients received the combination of two different systemic therapies. Of 126 patients completed at least 2 cycles of QS, 58 (46%) patients had longer break period (>4 weeks) between cycles. Among these patients, 37 (64%) patients received concurrent systemic therapy.

Palliative response and related factors

Palliative response could be assessed in 152 patients, and 121 patients has radiographic assessment. For the entire cohort, overall palliative response rate was 66%. Of the 44 patients received QS as a third course of radiation, palliative response rate was 68%. Of the 85 patients receiving three or more cycles of QS, 86% had palliative response (Table 2). Further, palliative response rates for photon and proton cohort were very similar (66%). On Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, only >2 year interval from prior RT (p<0.001) and 3–4 QS cycles (p<0.001) were related to palliation (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of palliative response

| QS cycles | Modailities | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| 1–2 cycles | 3–4 cycles | Photon | Proton | ||

|

| |||||

| Palliative response | 44.9% | 83.1% | 65.9% | 65.7% | 65.8% |

| Symptom relief | 45.6% | 72.7% | 60.0% | 60.3% | 60.2% |

| Radiographic response | |||||

| CR | 0 | 15.7% | 4.8% | 13.8% | 9.1% |

| PR | 21.6% | 57.1% | 41.3% | 43.1% | 42.1% |

| SD | 47.1% | 22.9% | 31.7% | 34.5% | 33.1% |

| PD | 31.4% | 4.3% | 22.2% | 8.6% | 15.7% |

| ORR (CR+PR) | 21.6% | 72.9% | 46.0% | 56.9% | 51.2% |

| DCR (CR+PR+SD) | 68.6% | 95.7% | 77.8% | 91.4% | 84.3% |

Abbreviations: QS, Quad Shot; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate.

Table 3.

Spearman’s rho correlation of palliative response with patient and clinical factors

| Palliative Response | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Correlation coefficient | Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

| ||

| KPS at palliative RT visit | ||

| < 70 | 0.110 | 0.179 |

| > 70 | ||

| Age | ||

| <70 | 0.062 | 0.447 |

| >70 | ||

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | −0.050 | 0.539 |

| Others | ||

| Primary tumor site | ||

| Oral cavity | 0.017 | 0.833 |

| Others | ||

| Salvage surgery before QS | ||

| No | −0.058 | 0.477 |

| Yes | ||

| Organ dysfunction at time of QS | ||

| No | 0.063 | 0.443 |

| Yes | ||

| Interval time > 2 years after prior RT | ||

| No | 0.301 | <0.001 |

| Yes | ||

| QS radiation technique | ||

| Photon | −0.001 | 0.986 |

| Proton | ||

| Concurrent systemic treatment | ||

| No | 0.103 | 0.206 |

| Yes | ||

| QS cycles | ||

| 1 or 2 | 0.401 | <0.001 |

| 3 or 4 | ||

The most common presenting symptoms were pain (82%), followed by dysphagia (66%), trismus (35%) and bleeding (21%). In total, symptoms improved in 60% of the whole cohort and 73% of patients receiving 3–4 QS cycles. Symptom relief rate was 60% in both modality cohorts. Among patients with post-QS radiographic assessment, 11 (9%) achieved complete response, and all of these patients received three or more cycles of QS. The objective response rate and disease control rate were 51% and 84%, respectively (Table 2, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A 65-year-old male with recurrent oral cavity carcinoma: (a) Baseline pre-treatment MR images demonstrate a large tumor mass (white arrows), (b) MR images after three cycles of Quad Shot demonstrate dramatic reduction of the tumor (white arrows).

Survival outcomes and prognostic factors

Median follow-up for all patients was 6.0 months (IQR 3.1–10.5) and 10.1 months (IQR 5.5–18.2) for living patients. Median OS was 6.3 months (95% CI 5.5–7.1), with 1-year OS 25.3% (95% CI 19.1–33.6%). Median LPFS was 5.1 months (95% CI 4.2–6.0), with 1-year PFS 17.7% (95% CI 12.6–24.9%). 37% of patients failed locally and fourteen patients (9%) were alive at the time of last follow-up. Of the 60 patients with locoregional failure, 32% achieved complete or partial response after QS, 42% had symptoms relief, and disease control rate was 60% in this small cohort. Specificlly, of 44 patients with multiple prior RT courses, median LPFS was 6.4 months (95%CI 5.3–7.6), and median OS was 8.4 months (95%CI 5.0–11.9).

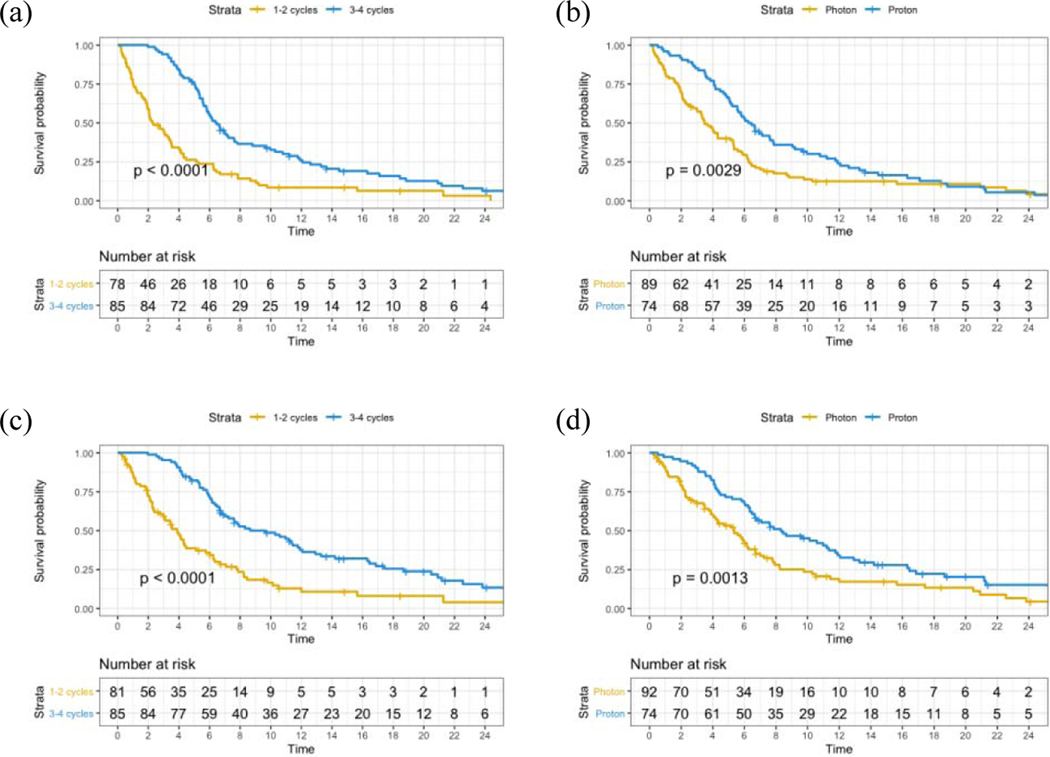

On univariate analysis, 3–4 QS cycles (p<0.001; Figure 2a), proton RT (p=0.003; Figure 2b), KPS >70 (p<0.001), >2 year interval after prior RT (p=0.026) and palliative response (p<0.001) were associated with improved LPFS. OS was improved with KPS >70 (p<0.001), non-SCC histology (p=0.019), absence of organ dysfunction (p=0.019), concurrent systemic treatment (p=0.033), palliative response (p<0.001), 3–4 QS cycles (p<0.001; Figure 2c) and proton RT (p=0.001; Figure 2d). The significant factors were included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model and the independent predictors of LPFS were KPS >70 (HR 0.54, p=0.001), proton RT (HR 0.67, p=0.021), palliative response (HR 0.41, p<0.001) and 3–4 QS cycles (HR 0.56, p=0.002). The independent predictors of improved OS were proton RT (HR 0.65, p=0.031), KPS >70 (HR 0.52, p=0.001), non-SCC (HR 0.51, p=0.005), palliative response (HR 0.50, p=0.001), and 3–4 QS cycles (HR 0.53, p=0.002; Table 4).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves: (a) Comparative LPFS in patients by QS cycles, (b) Comparative LPFS in patients by radiation modality, (c) Comparative OS in patients by QS cycles, (d) Comparative OS in patients by radiation modality.

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors for LPFS and OS

| LPFS | OS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Median LPFS (months) | UVA P value | MVA P value | MVA HR | Characteristics | Median OS (months) | UVA P value | MVA P value | MVA HR |

| KPS at time of QS | KPS at time of QS | ||||||||

| ≤ 70 (reference) | 3.8 [3.3–4.4] | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.54 [0.38–0.77] | ≤ 70 (reference) | 4.5 [3.4–5.5] | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.52 [0.35–0.78] |

| > 70 | 7.0 [5.9–8.1] | > 70 | 8.2 [5.4–11.0] | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| >2 years intervals | Histology | ||||||||

| No (reference) | 4.3 [3.4–5.2] | 0.026 | 0.104 | 0.74 [0.51–1.07] | SCC (reference) | 6.0 [5.1–6.9] | 0.019 | 0.005 | 0.51 [0.32–0.82] |

| Yes | 5.9 [4.9–6.9] | Others | 11.3 [3.2–19.5] | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| RT modalities | Organ dysfunction at QS | ||||||||

| Photon (reference) | 3.5 [2.8–4.2] | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.67 [0.45–0.94] | No (reference) | 7.6 [5.4–9.8] | 0.019 | 0.57 | 1.12 [0.76–1.67] |

| Proton | 6.2 [5.3–7.2] | Yes | 5.8 [4.7–6.8] | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| QS cycles | RT modalities | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 (reference) | 2.3 [1.4–3.2] | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.56 [0.38–0.81] | Photon (reference) | 5.4 [4.0–6.8] | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.65 [0.44–0.96] |

| 3 or 4 | 6.5 [5.5–7.4] | Proton | 8.3 [5.3–11.3] | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Palliation achieved | Concurrent therapy systemic | ||||||||

| No (reference) | 2.8 [1.3–4.3] | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.41 [0.28–0.62] | No (reference) | 5.3 [3.8–6.9] | 0.033 | 0.136 | 0.74 [0.50–1.10] |

| Yes | 6.2 [5.4–6.9] | Yes | 7.6 [5.9–9.3] | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age | NS | QS cycles |

|||||||

| Gender | NS | 1 or 2 (reference) | 3.9 [3.1–4.6] | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.53 [0.35–0.79] | |||

| Histology | NS | 3 or 4 | 9.6 [6.2–13.1] | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Salvage before QS Surgery | NS | Palliation achieved | |||||||

| Organ dysfunction | NS | No (reference) | 4.3 [3.4–5.1] | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.50 [0.33–0.77] | |||

| Concurrent treatment systemic | NS | Yes | 8.3 [5.4–11.1] | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age | NS | ||||||||

| Gender | NS | ||||||||

| Salvage Surgery before | NS | ||||||||

| QS | |||||||||

| >2 years intervals | NS | ||||||||

Toxicity

In total, 130 (78%) patients had baseline Grade 1–2 toxicities before the start of QS, 39% of patients were feeding tube dependent. Most QS-related toxicities were limited to Grade 1–2, with the most common being dermatitis (61%) and xerostomia (46%). There were 16 Grade 3 acute toxicities (10%) and two Grade 3 late toxicities (2%) in the entire cohort. No Grade 4–5 toxicities were observed. (Table 5)

Table 5.

Toxicities

| Baseline Toxicity (n=166) | |

| No. (%) | |

| Patients with Grade 1–2 toxicity | 130 (78.3) |

| Feeding tube dependent | 64 (38.6) |

|

| |

| Acute Toxicity (n=166) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| No. (%) | |

| Patients with Grade 1–2 toxicity | 149 (89.8) |

| Dermatitis | 101 (60.8) |

| Mucositis | 58 (34.9) |

| Trismus | 71 (42.8) |

| Dysphagia | 56 (33.7) |

| Xerostomia | 77 (46.4) |

| Voice change | 35 (21.1) |

| Lymphedema | 60 (36.1) |

| Patients with Grade 3 toxicity | 16 (9.6) |

| Dysphagia | 11 (6.6) |

| Dermatitis | 3 (1.8) |

| Trismus | 5 (3.0) |

| Mucositis | 1 (1.1) |

| Patients with Grade 4–5 toxicity | 0 |

|

| |

| Late Toxicity (n=105) | |

|

| |

| No. (%) | |

| Patients with Grade 1–2 toxicity | 62 (59.0) |

| Fibrosis | 26 (24.8) |

| Lymphedema | 30 (28.6) |

| Trismus | 26 (15.7) |

| Dysphagia | 16 (15.2) |

| Xerostomia | 18 (17.1) |

| Osteo- or soft tissue necrosis | 11 (10.5) |

| Patients with Grade 3 toxicity | 2 (1.9) |

| Osteo- or soft tissue necrosis | 1 (0.9) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (0.9) |

| Patients with Grade 4–5 toxicity | 0 |

Specifically, of the 44 patients received QS as third course of radiation, there were five cases of Grade 3 acute toxicities (11%) and two cases of Grade 3 late toxicities (5%). In addition, of the 83 patients treated with concurrent systemic therapy, the rate of overall Grade 3 acute toxicity and Grade 3 late toxicity were 16% and 1%, respectively. Of the 83 patients receiving QS alone, Grade 3 acute toxicity was observed in 3 patients (4%), and the rate of overall Grade 3 late toxicity was 1%.

DISCUSSION

Re-irradiation of recurrent HN cancer is often impeded by concerns for toxicity and reservations about the likelihood of therapeutic effect in potentially radioresistant tumors. However, for patients with severely symptomatic local recurrences, there are often no viable surgical and limited palliative medical alternatives to re-RT. The efficacy of non-definitive re-RT has not been studied as comprehensively. We present the largest series of last-line local therapy with the QS regimen in patients with locoregional recurrence(s) and limited life expectancy. In this retrospective cohort of 166 consecutively treated patients at our institution, palliative intent re-RT with the QS regimen resulted in median survival of 6.3 months and 66% of patients achieved a palliative response. These outcomes achieve comparable survival outcomes as with palliative systemic therapy in similar treatment-refractory settings, but with three to four times the response rate. Further, the majority (76%) of patients in our study failed systemic therapy prior to QS and eighty (48%) patients failed multiple lines, indicating that palliative re-RT with QS regimen offered considerable additional months of survival even for patients failed systemic treatment.

Two prior smaller studies from our institution on QS in the recurrent or metastatic setting reported 65% palliative response and median OS of 5.67 months with photon QS (n=75) and 73% palliative response and median OS of 9 months with proton QS (n=26).22,23 Given the fact that all patients in our current study had at least one prior course of definitive HN RT (compared to 40% and 88% in the two aforementioned studies), our results are favorable considering worse anticipated prognosis than in our prior studies. Even in patients with previously irradiated HN cancers, palliative re-RT with the QS regimen can achieve palliation in the majority of patients and extends survival for a considerable number of months, all with a minimal toxicity cost. Furthermore, it should be noted that despite being a palliative treatment, there was a small cohort who benefitted rather drastically (26% were alive at 1 year, and 9% were alive at 2 years), illustrating that QS is a durable treatment for some.

Palliative re-RT with the QS regimen is an effective last-line local treatment option, but concerns for radiation-related toxicities may pose a challenge to its implementation. In our cohort, only 18 patients (10.8%) developed early or late Grade 3 toxicities and no Grade 4 or 5 toxicities were observed, which is comparable to the 13% grade 3 or 4 toxicity reports with immunotherapy.6,7 Historical studies report that re-RT with concomitant systemic treatment produces favorable clinical outcomes at the cost of over 30% of patients sustaining grade 3 or higher toxicities.2,26–28 In our study, only 13 patients (15.7%) receiving concurrent systemic therapy sustained Grade 3 acute toxicity, suggesting that systemic therapy may be safely administered during QS in appropriately selected patients. The minimal toxicity may be a consequence of the four-week recovery interval between QS cycles which allows time for normal tissue repair. Additionally, the break also allows for reassessment, identification of patients with good performance status who are responding, and permits the adaptation of target volumes to account for tumor shrinkage between cycles. The low late toxicity is likely due to the poor prognosis of these patients, with the vast majority succumbing to disease before late toxicity can ensue.

Patient selection for palliative re-RT with the QS regimen is undefined, but rather a default option for those with no other viable alternatives. Prior studies have identified factors such as age, histology, performance status, organ dysfunction, salvage surgery, time interval from previous RT, and dose of re-RT to help stratify patients for definitive re-RT.29,30 Many of these factors did not profoundly influence the success of QS re-RT in the palliative re-RT setting. Our current study emphasizes the importance of increasing number of QS cycles and performance status to outcomes. Of note, our data shows an unexpected favorable survival outcome for patients with more than one prior RT course. This may be related to the fact that the majority of these heavily treated patients had KPS ≥ 70 (89%), treated with proton RT (61%) and completed at least 3 cycles of QS (59%). Regardless, the finding indicates that multiple prior RT courses should not necessarily be a deterrent to consideration of QS RT, as it appears to be effective and minimally toxic.

Proton therapy is increasingly utilized for HNC treatment because of its physical properties and dosimetric advantages.31–35 Compared to photons, protons minimize the integral dose to normal tissues, which may especially benefit previously irradiated patients.36,37 Thus, reirradiation is one of the indications for which insurance companies approve proton beam therapy. Our study revealed that proton RT was one of the independent predictors of LPFS (HR 0.67, p=0.021) and OS (HR 0.65, p=0.031). Proton therapy may offer survival advantages in the setting of palliative reirradiation, but it should be explored prospectively given that imbalances between two modality groups are not easily controlled in our retrospective study.

Although this is the first and largest report of QS regimen for non-curative re-irradiation to date, limitations exist. The retrospective nature and consequent biases could potentially confound our findings. Toxicity and palliative response were determined by reviewing medical records, and required consensus between multiple reviewers to distinguish toxicity from prior RT versus new toxicity acquired during QS. A major consideration in the overall low toxicity rate is the fact that many patients did not live long enough to have late radiation toxicity assessments. However, in the acute setting, toxicity was minimal and further cycles of QS were not stopped due to toxicity but rather due to decline in performance status or disease progression.

In conclusion, our data revealed that there is a clear palliative benefit with QS for both modalities (photon and proton) even in patients with previously radiated HNC. Response rates are high and it well tolerated with low acute toxicity. Additionally, KPS>70, more QS cycles and proton therapy are associated with survival improvements.

Highlights:

QS is an effective palliative therapy in patients with previously irradiated HNC.

Administration of 3–4 QS cycles predicts palliative response and improved survival.

Proton therapy has potential survival benefits in the palliative re-RT setting.

Acknowledgment:

Dr. Fan’s research was partly supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC No. 201706370238).

Funding:

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and by the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spencer SA, Harris J, Wheeler RH, et al. : Final report of RTOG 9610, a multi-institutional trial of reirradiation and chemotherapy for unresectable recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 30:281–8, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer CJ, Harris J, Horwitz EM, et al. : Phase II study of low-dose paclitaxel and cisplatin in combination with split-course concomitant twice-daily reirradiation in recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 9911. J Clin Oncol 25:4800–5, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward MC, Riaz N, Caudell JJ, et al. : Refining Patient Selection for Reirradiation of Head and Neck Squamous Carcinoma in the IMRT Era: A Multi-institution Cohort Study by the MIRI Collaborative. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 100:586–594, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forastiere AA, Leong T, Rowinsky E, et al. : Phase III comparison of high-dose paclitaxel + cisplatin + granulocyte colony-stimulating factor versus low-dose paclitaxel + cisplatin in advanced head and neck cancer: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1393. J Clin Oncol 19:1088–95, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. : Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 359:1116–27, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr., Fayette J, et al. : Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N Engl J Med 375:1856–1867, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet 393:156–167, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. : Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet (London, England) 394:1915–1928, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laursen M, Specht L, Kristensen CA, et al. : An Extended Hypofractionated Palliative Radiotherapy Regimen for Head and Neck Carcinomas. Front Oncol 8:206, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kancherla KN, Oksuz DC, Prestwich RJ, et al. : The role of split-course hypofractionated palliative radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 23:141–8, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-mamgani A, Tans L, Van rooij PH, et al. : Hypofractionated radiotherapy denoted as the “Christie scheme”: an effective means of palliating patients with head and neck cancers not suitable for curative treatment. Acta Oncol 48:562–70, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal JP, Nemade B, Murthy V, et al. : Hypofractionated, palliative radiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol 89:51–6, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farina E, Capuccini J, Macchia G, et al. : Phase I-II Study of Short-course Accelerated Radiotherapy (SHARON) for Palliation in Head and Neck Cancer. Anticancer Res 38:2409–2414, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohanti BK, Umapathy H, Bahadur S, et al. : Short course palliative radiotherapy of 20 Gy in 5 fractions for advanced and incurable head and neck cancer: AIIMS study. Radiother Oncol 71:275–80, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens CM, Huang SH, Fung S, et al. : Retrospective study of palliative radiotherapy in newly diagnosed head and neck carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 81:958–63, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen NT, Doerwald-Munoz L, Zhang H, et al. : 0–7-21 hypofractionated palliative radiotherapy: an effective treatment for advanced head and neck cancers. Br J Radiol 88:20140646, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monnier L, Touboul E, Durdux C, et al. : Hypofractionated palliative radiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer: the IHF2SQ regimen. Head Neck 35:1683–8, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porceddu SV, Rosser B, Burmeister BH, et al. : Hypofractionated radiotherapy for the palliation of advanced head and neck cancer in patients unsuitable for curative treatment--”Hypo Trial”. Radiother Oncol 85:456–62, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen AM, Vaughan A, Narayan S, et al. : Palliative radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: toward an optimal fractionation scheme. Head Neck 30:1586–91, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soni A, Kaushal V, Verma M, et al. : Comparative Evaluation of Three Palliative Radiotherapy Schedules in Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. World J Oncol 8:7–14, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finnegan TS, Bhatt NH, Shaughnessy JN, et al. : Cyclical hypofractionated radiotherapy technique for palliative treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer: institutional experience and review of palliative regimens. J Community Support Oncol 14:29–36, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lok BH, Jiang G, Gutiontov S, et al. : Palliative head and neck radiotherapy with the RTOG 8502 regimen for incurable primary or metastatic cancers. Oral Oncol 51:957–62, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma J, Lok BH, Zong J, et al. : Proton Radiotherapy for Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Cancers with Palliative Quad Shot. Int J Part Ther 4:10–19, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, et al. : From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 50 Suppl 1:122S–50S, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. : New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 45:228–247, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salama JK, Vokes EE, Chmura SJ, et al. : Long-term outcome of concurrent chemotherapy and reirradiation for recurrent and second primary head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 64:382–91, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tortochaux J, Tao Y, Tournay E, et al. : Randomized phase III trial (GORTEC 98–03) comparing re-irradiation plus chemotherapy versus methotrexate in patients with recurrent or a second primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, treated with a palliative intent. Radiother Oncol 100:70–5, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Y, Faivre L, Laprie A, et al. : Randomized trial comparing two methods of re-irradiation after salvage surgery in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Once daily split-course radiotherapy with concomitant chemotherapy or twice daily radiotherapy with cetuximab. Radiother Oncol 128:467–471, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riaz N, Hong JC, Sherman EJ, et al. : A nomogram to predict loco-regional control after re-irradiation for head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol 111:382–7, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanvetyanon T, Padhya T, McCaffrey J, et al. : Prognostic factors for survival after salvage reirradiation of head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 27:1983–91, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno AC, Frank SJ, Garden AS, et al. : Intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT) – The future of IMRT for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncology 88:66–74, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JK, Leeman JE, Riaz N, et al. : Proton Therapy for Head and Neck Cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 19:28, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Han S, Zhu J, et al. : Proton versus photon radiation-induced cell death in head and neck cancer cells. Head Neck 41:46–55, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchard P, Garden AS, Gunn GB, et al. : Intensity-modulated proton beam therapy (IMPT) versus intensity-modulated photon therapy (IMRT) for patients with oropharynx cancer - A case matched analysis. Radiother Oncol 120:48–55, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brodin NP, Kabarriti R, Pankuch M, et al. : A Quantitative Clinical Decision-Support Strategy Identifying Which Patients With Oropharyngeal Head and Neck Cancer May Benefit the Most From Proton Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 104:540–552, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romesser PB, Cahlon O, Scher ED, et al. : Proton Beam Reirradiation for Recurrent Head and Neck Cancer: Multi-institutional Report on Feasibility and Early Outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 95:386–95, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phan J, Sio TT, Nguyen TP, et al. : Reirradiation of Head and Neck Cancers With Proton Therapy: Outcomes and Analyses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 96:30–41, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]