Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

We sought to characterize the timing of administration of prehospital Tranexamic Acid (TXA) and associated outcome benefits.

BACKGROUND:

TXA has been shown to be safe in the prehospital setting post-injury.

METHODS:

We performed a secondary analysis of a recent prehospital randomized TXA clinical trial in injured patients. Those who received prehospital TXA within 1hr (EARLY) from time of injury were compared to those who received prehospital TXA beyond 1hr (DELAYED). We included patients with a shock index of > 0.9. Primary outcome was 30-day mortality. Kaplan-Meier and Cox Hazard regression were utilized to characterize mortality relationships.

RESULTS:

EARLY and DELAYED patients had similar demographics, injury characteristics and shock severity but DELAYED patients had greater prehospital resuscitation requirements and longer prehospital times. Stratified Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated significant separation for EARLY patients (N =238, log-rank chi-square test, 4.99; P = .03) with no separation for DELAYED patients (N=238, log-rank chi-square test, 0.04; P = .83). Stratified Cox Hazard regression verified, after controlling for confounders, that EARLY TXA was associated with a 65% lower independent hazard for 30-day mortality (HR 0.35, 95%CI 0.19–0.65, P = .001) with no independent survival benefit found in DELAYED patients (HR 1.00, 95%CI 0.63–1.59, P = .999). EARLY TXA patients had lower incidence of multiple organ failure and 6-hour and 24-hour transfusion requirements compared to placebo.

CONCLUSIONS:

Administration of prehospital TXA within 1 hour from injury in patients at risk of hemorrhage is associated with 30-day survival benefit, lower incidence of multiple organ failure, and lower transfusion requirements.

MINI-ABSTRACT:

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial showed that early (within 1hr of injury) prehospital tranexamic acid (TXA) is associated with a 30-day survival benefit. Early prehospital TXA was also associated with reduced multiple organ failure and transfusion requirements.

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhage remains a leading cause of preventable death in both civilian and military injured patients.1–6 A recent call for zero preventable deaths by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine focuses on strategies to mitigate the physiologic consequences of hemorrhagic shock.7 In addition to early balanced transfusion of blood components or whole blood transfusion, resuscitative adjuncts including Tranexamic Acid (TXA) improve survival after a patient has arrived at definitive care.8–13 The timing of TXA administration during the in-hospital phase of care is important and associated with differential efficacy and safety outcomes.8, 14 More recent clinical trials following traumatic injury verified the importance of the timing of intervention and the significance of the prehospital environment to maximize benefit for the injured patient at risk of hemorrhage.15–17

Recent randomized clinical trials demonstrate the safety of prehospital TXA across a spectrum of injury types and severity.18, 19 These types of prehospital clinical trials following injury commonly require broad, pragmatic inclusion criteria with limited exclusion criteria due to the complexity of environment where enrollment occurs. Due to these factors, the most appropriate injured patient population and the timing of prehospital TXA administration to maximize outcome benefits remain poorly characterized.

Our objective is to characterize the timing of prehospital TXA administration relative to the time of injury and associations with differential outcome benefits. We hypothesized that early prehospital TXA administration is associated with efficacy and safety benefits as compared to delayed prehospital TXA administration.

METHODS

We performed a post hoc secondary analysis of the STAAMP prehospital clinical trial. The STAAMP trial was a pragmatic, phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial that examined outcomes in injured patients at risk for hemorrhage who received prehospital TXA during air medical or ground transport. The study included injured patients at risk for hemorrhage transported from the scene or transferred from an outside emergency department to a participating trauma center within 2 hours of injury. Patients were primarily randomized to receive TXA (1g bolus over 10 minutes en route to hospital) vs. placebo in the prehospital phase. Those in the treatment arm were subsequently randomized to 1 of 3 in-hospital phase TXA dosing regimens (no additional TXA, 1g of TXA infused over 8 hours, or bolus of 1g TXA followed by 1g TXA infusion over 8 hours). The study was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (Investigational New Drug 121102), the Human Research Protection Offices of the US Department of Defense, and institutional review boards of all participating sites as previously described.18 This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.20

Study Population

Eligibility criteria for the current secondary analysis mirrored that of the STAAMP trial18 and included those patients with hypotension (systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg) and/or tachycardia (heart rate ≥ 110 per minute) during the prehospital phase of care prior to trauma center arrival. Additional exclusion criteria for the current analysis included those patients with a qualifying vital sign shock index (heart rate/systolic blood pressure) ≤ 0.9 to minimize inclusion of those patients with negligible risk of hemorrhage. This was to focus the analysis on those patients with a greater risk of hemorrhage and shock where TXA may have a beneficial effect.

For the purposes of this secondary analysis, patients from the primary STAAMP trial were stratified into TXA (all 3 in-hospital dosing regimens) vs. placebo and comparisons were limited to prehospital randomization arms.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this secondary analysis was 30-day mortality. Secondary outcomes included 24-hour mortality, multiple organ failure (MOF) as defined by the Denver Multiple Organ Dysfunction scoring system,21 nosocomial infection, acute lung injury, and 6 and 24-hour in-hospital blood component transfusion. We also analyzed presenting measures of coagulation (international normalized ratio [INR] and thromboelastography [TEG]), and measures of safety including pulmonary embolism (PE), deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and seizures. All analyses were performed using intention-to-treat randomized assignment.

Time of injury in the primary STAAMP trial was estimated using data from the corresponding Emergency Communications Center and Emergency Medical Service. Timing of prehospital TXA administration for the current secondary analysis was defined as EARLY (within 1 hour from estimated time of injury during the prehospital phase of care) and DELAYED (greater than 1 hour from estimated time of injury during the prehospital phase of care).

Statistical Analysis

We first examined whether the treatment effect of prehospital TXA versus placebo on 30-day mortality varied across EARLY and DELAYED subgroups. The interaction between prehospital TXA treatment and timing of administration was assessed for statistical significance, accounting for clustering by study site. We then evaluated 30-day mortality across treatment arms in both EARLY and DELAYED subgroups using Chi-square test.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis on 24-hour and 30-day mortality was performed to compare TXA treatment versus placebo patients across EARLY and DELAYED subgroups using log-rank testing. A multivariate regression analysis of survival using Cox proportional-hazard modeling clustered on study site with adjustment for confounders was performed to verify these unadjusted findings. The model was built on the primary outcome of 30-day mortality for EARLY patients. We selected covariates based on biological plausibility and strong univariate associations for the model. To prevent overfitting, we only included covariates with a p-value < 0.1 and confounding covariates that changed the hazard ratio of TXA treatment by >10% in the final model.22 All covariates included in the final model passed linearity assumption and proportional-hazards assumption based on Schoenfeld residuals and Grambsch and Therneau’s method.23, 24 The final model had adequate goodness-of-fit based on Gronnesby and Borgan test.25

Secondary outcomes were tested using Chi-square test for binary variables and non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Patient demographics, injuries and outcomes of interest were represented using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies (%) and were compared using Chi-square or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were compared using t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Statistical significance was defined at a two-sided p-value < 0.05. Stata SE 15.1 (College Station, TX) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

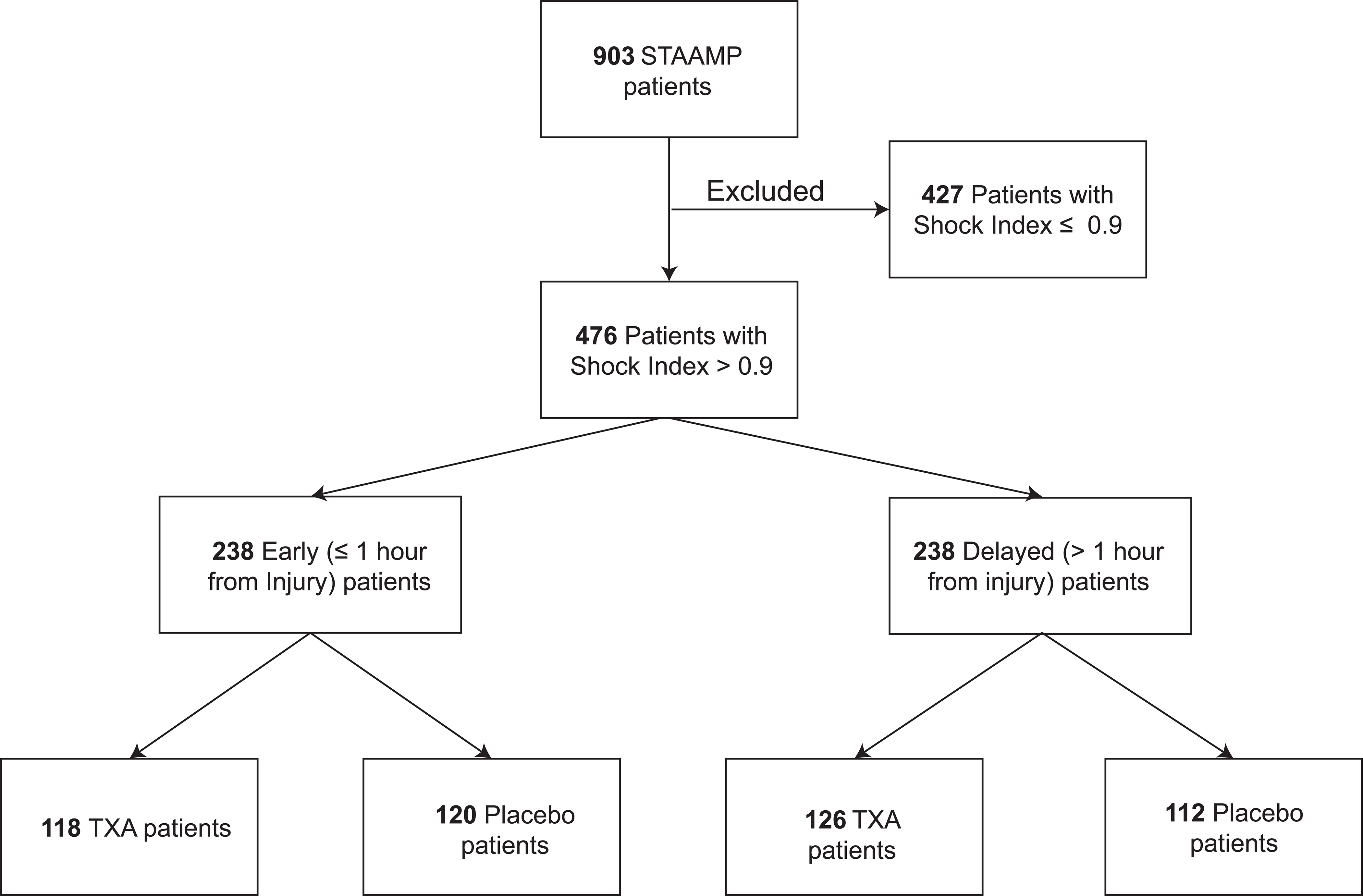

For the current secondary analysis, 476 patients met all inclusion and no exclusion criteria (EARLY N=273, DELAYED N=273). (Figure 1). Overall, patients were moderately injured with median Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 14 (IQR, 6–37), and overall mortality of 11.5%. The majority of injuries were blunt (83.6%) and were most commonly due to motor vehicle collision (57.9%). Penetrating mechanism comprised 16.4% of injuries and were largely due to firearms (47.4%) or stabbings (42.3%). Randomization of the primary STAAMP trial was excellent, with no significant differences in baseline patient characteristics between treatment arms.18

Figure 1.

Patient Selection Flowchart

Overall, EARLY and DELAYED patients had similar demographics, injury characteristics, and shock severity. DELAYED patients had greater resuscitation requirements including higher prehospital crystalloid volume and more frequent prehospital packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusion. Additionally, DELAYED patients were more likely to be transferred from a referral hospital and were more frequently intubated prior to arrival to a participating trauma center (Table 1). Compliance with prehospital TXA dosing was high with 95.8% of EARLY prehospital TXA and 97.6% of DELAYED prehospital TXA patients receiving the full prehospital dose.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by EARLY and DELAYED Subgroups

| Characteristic | Early (≤1 hr) TXA (N=238) | Delayed (>1 hr) TXA (N=238) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 38.0 (26.0–55.0) | 39.0 (26.0–57.0) | 0.52 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 167 (70.2) | 165 (70) | 0.84 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.80 | ||

| White | 188 (79.0) | 194 (81.5) | |

| African American | 26 (10.9) | 18 (7.6) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Other | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Unknown | 21 (8.8) | 23 (9.7) | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, n (%) | 16 (6.7) | 17 (7.1) | 0.78 |

| Injury Mechanism, n (%) | 0.84 | ||

| Blunt | 199 (83.6) | 199 (83.6) | |

| Penetrating | 39 (16.4) | 39 (16.4) | |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 53 (22.2) | 71 (29.8) | 0.06 |

| Transported from referral hospital, n (%) | 13 (5.4) | 51 (21.4) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital crystalloid volume, median (IQR), mL | 500.0 (125.0–1000.0) | 800.0 (250.0–1500.0) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital peripheral red blood cell transfusion, n (%) | 28 (11.7) | 45 (18.9) | 0.03 |

| Initial Glasgow Coma Scale score, median (IQR) | 14 (12–15) | 14 (8–15) | 0.23 |

| Initial Glasgow Coma Scale score <8, n (%) | 48 (20.2) | 64 (26.9) | 0.08 |

| Prehospital systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mmHg | 93 (80–122) | 100 (80–123) | 0.51 |

| Prehospital heart rate, median (IQR), min | 120 (109–130) | 120 (110–130) | 0.56 |

| Prehospital shock index, median (IQR) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 (1.0–1.4) | 0.50 |

| Prehospital intubation, n (%) | 49 (20.6) | 77 (32.4) | 0.004 |

| Prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation, n (%) | 4 (1.7) | 9 (3.8) | 0.16 |

| Prehospital transport time, median (IQR), min | 33.0 (27.0–41.0) | 44.5 (35.0–56.0) | <0.001 |

| Injury Severity Score, median (IQR) | 14 (6–26) | 17 (8–27) | 0.26 |

| Abdomen AIS score, median (IQR) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.39 |

| Chest AIS score, median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 0.10 |

| Extremity AIS score, median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–2) | 0.14 |

| Face AIS score, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.96 |

| Head AIS score, median (IQR) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–3) | 0.17 |

| Preinjury vitamin K antagonist, n (%) | 5 (2.1) | 5 (2.1) | 0.99 |

| Preinjury antiplatelet medication, n (%) | 22 (9.2) | 25 (10.5) | 0.66 |

| Received TXA randomized treatment, n (%) | 118 (50.0) | 126 (52.9) | 0.46 |

| Time to TXA treatment, median (IQR), min | 47.0 (40.0–54.0) | 78.5 (68.0–100.0) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale; TXA, tranexamic acid.

Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

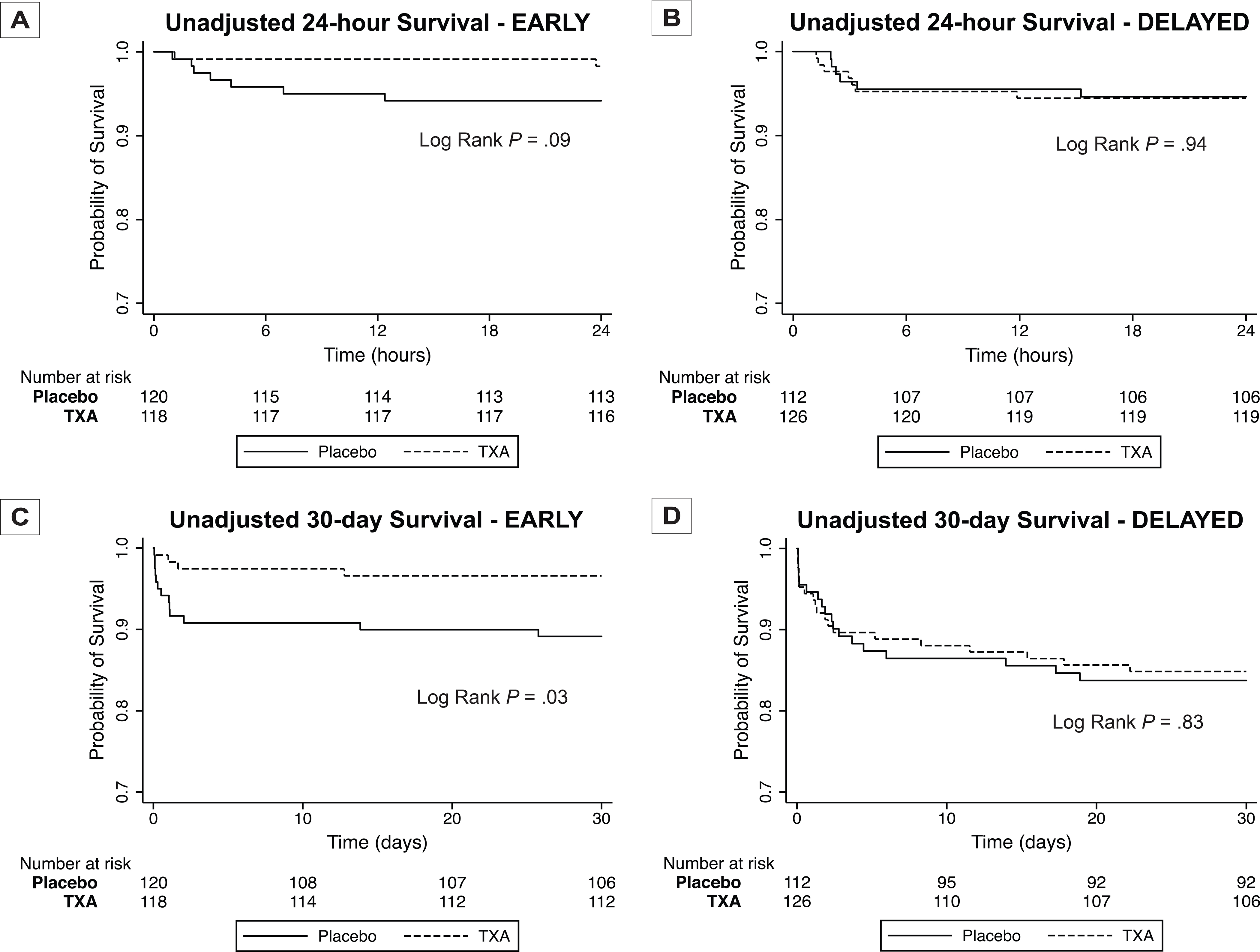

We first evaluated the association of prehospital TXA treatment and timing of administration on 30-day mortality. The prehospital TXA and time of administration interaction was assessed utilizing cox regression clustered by trial site which was statistically significant (P = .03). EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with significantly reduced 30-day mortality compared to placebo (3.5% vs. 10.9%; difference −7.5; 95% CI, −14.0% to −0.9%; P = .03) with no significant difference in the DELAYED group (15.2% vs. 16.4%; difference −1.2; 95%CI −10.5% to 8.5%; P = .81). Next, we performed 24-hour and 30-day Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing prehospital TXA vs placebo across EARLY and DELAYED subgroups (Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference in 24-hour mortality across treatment arms in both EARLY (log-rank chi-square test, 2.8; P = .09) and DELAYED groups (log-rank chi-square test, 0.01; P = .94). However, patients that received EARLY prehospital TXA demonstrated significant separation in 30-day mortality (log-rank chi-square test, 4.99; P = .03) with no significant separation found for DELAYED patients (log-rank chi-square test, 0.04; P = .83).

Figure 2.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis for 24-hour and 30-day Survival Comparing Prehospital TXA and Placebo Patients for EARLY (A, C) and DELAYED (B, D) Subgroups

P values were calculated using log-rank testing.

Multivariate analysis of 30-day survival using a Cox proportional-hazard model to adjust for clinically relevant and significant covariates verified that EARLY prehospital TXA was independently associated with a survival benefit (HR 0.35, 95%CI 0.19–0.65, P = .001) when compared to placebo, representing a 65% lower hazard for 30-day mortality (Table 2). No independent survival benefit was found in DELAYED prehospital TXA patients (HR 1.00, 95%CI 0.63–1.59, P = .99).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox-Hazard Regression Model for 30-day Mortality in EARLY and DELAYED Patients

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| EARLY | |||

|

| |||

| TXA (reference: placebo) | 0.35 | 0.19–0.65 | 0.001 |

| Pre-hospital blood transfusion | 1.65 | 1.14–2.37 | 0.01 |

| Pre-hospital crystalloid > 600 mL | 1.92 | 0.55–6.69 | 0.31 |

| Initial GCS<8 | 8.25 | 3.63–18.72 | <0.001 |

| ISS > 14 | 1.82 | 1.02–3.25 | 0.04 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.70 |

|

| |||

| DELAYED | |||

|

| |||

| TXA (reference: placebo) | 1.00 | 0.63–1.60 | 0.99 |

| Pre-hospital blood transfusion | 1.16 | 1.10–1.22 | <0.001 |

| Pre-hospital crystalloid > 600 mL | 1.56 | 1.29–1.89 | <0.001 |

| Initial GCS<8 | 5.53 | 1.9–16.00 | 0.002 |

| ISS > 14 | 3.39 | 1.66–6.93 | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.02–1.05 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: TXA, tranexamic acid; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ISS, Injury Severity Score.

We then compared incidence of MOF, nosocomial infection and acute lung injury across treatment arms in both EARLY and DELAYED groups. EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with decreased incidence of MOF compared to placebo (P = .02) (Table 3). No significant difference in MOF incidence was observed between treatment arms in the DELAYED group (P = .51). Incidence of nosocomial infection and acute lung injury were not significantly different across randomization groups in either EARLY or DELAYED subgroups.

Table 3.

Comparison of Multiple Organ Failure (MOF), Nosocomial Infection (NI), Acute Lung Injury (ALI) Across Prehospital TXA and Placebo Patients Stratified by EARLY and DELAYED Groups

| EARLY | DELAYED | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Placebo (N=120) | TXA (N=118) | P a | Placebo (N=112) | TXA (N=126) | P a | |

|

| ||||||

| MOF, n (%) | 15 (12.5) | 5 (4.2) | 0.02 | 12 (10.7) | 17 (13.5) | 0.51 |

| NI, n (%) | 18 (15.0) | 20 (17.0) | 0.68 | 21 (18.8) | 29 (23.0) | 0.43 |

| ALI, n (%) | 11 (9.2) | 9 (7.6) | 0.67 | 15 (13.4) | 15 (11.9) | 0.73 |

Abbreviations: MOF, multiple organ failure; NI, nosocomial infection; ALI, acute lung injury.

P values were calculated using the Pearson χ2 test.

We also assessed 6-hour and 24-hour blood and blood component transfusion requirements across treatment arms in EARLY and DELAYED subgroups. EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with a lower incidence of requiring any blood transfusion in the first 6 hours (31.4% vs. 46.7%, P = .02) and decreased volume of 6-hour PRBC, platelet and plasma transfusion when compared to placebo (Table 4). EARLY prehospital TXA was also associated with a decreased 24-hour volume of PRBC, platelet and plasma transfusion. Importantly, EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with reduced incidence of the need for massive transfusion (≥ 10 units PRBC in first 24-hours; 2.5% vs. 9.2%, P = .03) without significant difference between treatment arms in the DELAYED group (7.9% TXA vs. 10.7% placebo, P = .46). No significant differences were observed between DELAYED prehospital TXA and placebo for 6 and 24-hour transfusion.

Table 4.

Comparison of 6-hour and 24-hour Blood and Blood Component Transfusion and Measures of Coagulopathy Across Prehospital TXA and Placebo Patients Stratified by EARLY and DELAYED Groups

| EARLY | DELAYED | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Median (IQR) | Placebo | TXA | P a | Placebo | TXA | P a |

|

| ||||||

| 6-hour Transfusions | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| PRBC | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–1) | 0.003 | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.92 |

| Plasma | 0 (0–0.5) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.32 |

| Platelets | 0 (0, 4) | 0 (0–1) | 0.003 | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.92 |

|

| ||||||

| 24-hour Transfusions | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| PRBC | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–2) | 0.01 | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 0.71 |

| Plasma | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0.002 | 0 (0–0.5) | 0 (0–0) | 0.28 |

| Platelets | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.04 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.48 |

|

| ||||||

| Measures of Coagulopathy | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| INRb | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.57 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.70 |

| ACT, secc | 113 (105–121) | 113 (105–121) | 0.46 | 113 (105–128) | 113 (105–121) | 0.21 |

| α-Angled | 73.9 (69.0–76.6) | 71.1 (67.0–75.6) | 0.04 | 71.1 (65.4–75.7) | 71.9 (66.2–74.8) | 0.82 |

| K-time, mine | 1.4 (1.1–2.0) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) | 0.41 | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) | 0.92 |

| MAf | 62.2 (56.3–67.5) | 61.9 (57.8–67.3) | 0.90 | 62.2 (56.8–67.1) | 59.3 (55.2–64.9) | 0.09 |

| LY30, %g | 2.6 (1.5–40.0) | 10 (2.2–50.0) | 0.08 | 20 (2.6–60) | 2.8 (1.2–30.0) | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: PRBC, packed red blood cells; INR, international normalized ratio; ACT, activated clotting time; MA, maximum amplitude; LY30, Lysis at 30 minutes; ACT, activated clotting time.

P values were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Unavailable in 47 in the EARLY group and 49 in the DELAYED group (n = 226; n = 224).

Unavailable in 70 in the EARLY group and 76 in the DELAYED group (n = 203; n = 197).

Unavailable in 51 in the EARLY group and 57 in the DELAYED group (n = 222; n = 216).

Unavailable in 57 in the EARLY group and 59 in the DELAYED group (n = 216; n = 214).

Unavailable in 52 in the EARLY group and 58 in the DELAYED group (n = 221; n =215).

Unavailable in 122 in the EARLY group and 123 in the DELAYED group (n = 151; n = 150).

We then examined measures of coagulopathy including presenting INR and TEG parameters on arrival to the definitive trauma center across treatment arms in EARLY and DELAYED subgroups. There was no significant difference in INR between prehospital TXA and placebo in either EARLY or DELAYED subgroups. TEG comparison demonstrated that EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with a decreased α angle compared to placebo (P = .04) (Table 4). In the DELAYED subgroup, prehospital TXA was associated with a significantly decreased LY30 compared to placebo (P < .01).

Lastly, we evaluated measures of safety for EARLY and DELAYED prehospital TXA by comparing rates of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and seizures across treatment arms. There were no significant differences in DVT, PE, overall VTE or seizures between prehospital TXA and placebo across both EARLY and DELAYED subgroups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of Measures of Safety including DVT, PE, Overall VTE and Seizure Across Prehospital TXA and Placebo Patients Stratified by EARLY and DELAYED Groups

| EARLY | DELAYED | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Placebo (N=120) | TXA (N=118) | P a | Placebo (N=112) | TXA (N=126) | P a | |

|

| ||||||

| Measures of Safety | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| DVT, n (%) | 5 (4.2) | 3 (2.5) | 0.49 | 1 (0.9) | 6 (4.8) | 0.08 |

| PE, n (%) | 3 (2.5) | 4 (3.4) | 0.68 | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.4) | 0.75 |

| VTE, n (%) | 8 (6.7) | 7 (5.9) | 0.82 | 2 (1.8) | 8 (6.3) | 0.08 |

| Seizure, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.32 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.6) | 0.63 |

Abbreviations: DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

P values were calculated using the Pearson χ2 test.

DISCUSSION

Hemorrhage and acute traumatic coagulopathy are leading causes of death following traumatic injury.1–6 How one is resuscitated and the adjuncts utilized in addition to blood and blood component is important. Previous studies demonstrate that early use of TXA in injured patients at risk for bleeding improves survival.8, 10, 14 A recent randomized clinical trial showed that prehospital TXA administration is safe, but did not result in statistically significant survival benefit between treatment arms.18 The results of the current secondary analysis demonstrate a significant survival benefit in patients with at least mild to moderate shock who received prehospital TXA within 1 hour from injury. This survival benefit remained robust after multivariate adjustment, with a 65% lower hazard for 30-day mortality in patients that received EARLY prehospital TXA when compared to placebo.

Prior investigations demonstrate that injured patients with shock index > 0.9 have higher mortality rates and risk for critical bleeding.26, 27 Additionally, a prospective cohort study evaluating the differential effect of TXA in patients with and without shock showed that TXA reduced mortality and MOF only in patients with shock.28 Because patients enrolled in the primary STAAMP trial demonstrated a broad spectrum of injury and shock severity, only patients with initial prehospital shock index > 0.9 were included for this secondary analysis in order to capture those at highest risk for hemorrhage and mortality. After exclusion of patients without evidence of shock, EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with not only a 30-day survival benefit, but also reduced incidence of MOF and lower 6-hour and 24-hour transfusion volumes. Shock index can be easily calculated and used as a stratification tool in the prehospital setting to identify patients that may benefit from prehospital TXA following injury. These findings can help guide appropriate patient selection and timing of prehospital TXA administration after injury.

While the majority of studies examining the effect of TXA in injured patients are limited to the in-hospital setting, the importance of timing in TXA administration is a common theme.8, 11, 14, 17, 29 The CRASH-2 trial is the largest randomized control trial evaluating the effect of in-hospital TXA within 8 hours of injury on mortality. This study showed significant reduction in overall mortality in those randomized to TXA.8 Importantly, a post-hoc exploratory analysis showed that those receiving TXA within 1 hour of injury had the greatest reduction in mortality due to bleeding.14 Further analysis confirmed that the time-dependent effect of TXA was not explained by differences in mechanism of injury, GSC or blood pressure.29 Extrapolating from the knowledge that early TXA administration improves survival and that the majority of deaths from traumatic hemorrhage occur within the first hours following injury, characterizing appropriate protocols and patient selection for prehospital TXA administration is paramount.

The time-dependent effect of TXA on survival may be explained by the timing of biological response following injury. Acute traumatic coagulopathy (ATC) involves a cascade of events following tissue trauma and hypoperfusion resulting in the activation of anticoagulant and fibrinolytic pathways.30–32 ATC has been identified as a distinct entity present at the time of injury and is associated with poor outcomes.30, 32, 33 TXA occupies binding sites on tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) activated plasminogen, preventing the conversion to plasmin and blocking the interaction with fibrin. tPA reaches peak concentration approximately 30 min following injury with subsequent peak levels of plasminogen at 1 hour.29, 34 Administration of TXA prior to peak plasminogen concentration, ameliorating the downstream fibrinolytic and inflammatory effects of plasmin, may explain the observed benefits when TXA is given early. The EARLY subgroup in this analysis had a median time to treatment of 47 minutes with improved clinical outcomes, solidifying that early administration of TXA confers maximum benefit.

The magnitude of shock and a dysfunctional inflammatory response following traumatic injury have also been implicated in the development of postinjury MOF.35, 36 By reducing the activation of plasmin and preventing downstream plasmin-mediated proinflammatory cytokine release, TXA has been postulated to have an anti-inflammatory effect.37 The current results demonstrate that EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with significantly decreased incidence of MOF (4.2% vs. 12.5%, P = .02).

TXA following injury has been shown to have varying effect on transfusion requirements.8, 9, 38, 39 In this analysis, we observed decreased volume of 6-hour and 24-hour blood and blood component transfusion in patients receiving EARLY prehospital TXA, with no significant observed differences in transfusion requirements in the DELAYED group. Further, EARLY prehospital TXA was associated with reduced massive packed red blood cell transfusion (2.5% vs. 9.2%, P = .03), which was not observed in the DELAYED group. Timely administration of TXA in the prehospital phase is associated with a reduced risk of blood product transfusion after injury.

Evidence surrounding measures of coagulopathy after TXA administration in traumatic injury is limited.9, 19, 40 There were no differences across randomization arms in the primary STAAAMP trial and no differences found in INR in the current secondary analysis. TEG measurements occurred in-hospital after either EARLY or DELAYED prehospital TXA was administered. The current subgroup results of decreased α angle (EARLY TXA vs. placebo) and LY30 in (DELAYED TXA vs. placebo) do not provide a underlying mechanism for the outcomes demonstrated. Additionally, the observed differences in alpha angle may not be clinically significant. It may be that in-hospital thromboelastography may be unable to appropriately characterized differences in LY30 following a prehospital TXA intervention. Further prospective analysis comparing measures of coagulopathy and fibrinolysis following prehospital TXA treatment are needed to provide clarity.

While we were not able to comment on changes in coagulation parameters due to study design, prior investigations have suggested improved measures of coagulopathy after TXA administration. In particular, Kunze-Szikszay et al.40 assessed the effects of prehospital TXA on rotational thrombelastometry and showed no significant changes in parameters following TXA treatment. This was in contrast to a study by Theusinger et al.41 which compared coagulation status in trauma patients at the scene and on arrival to the emergency department and showed dramatic deterioration in measures of coagulation between the two time points.

Most importantly, we report no significant increase in adverse effects, including VTE and seizure, across treatment arms in both EARLY and DELAYED groups. This corresponds to the primary trials results18 and demonstrates the safety of prehospital TXA as has been documented in other recent prehospital clinical trials focused on traumatic brain injury.19

While this secondary analysis has robust findings, there are several limitations. This was a post-hoc secondary analysis that was not prespecified in the primary STAAMP trial protocol. The study was not randomized across EARLY and DELAYED patients, and there were significant differences between the two subgroups. While we adjusted for these differences and confounding variables across the groups using a multivariate Cox proportional model, potential for residual confounding exists. Additionally, the primary STAAMP trial included patients from multiple trauma centers, which could affect conclusions based on differences across participating sites. However, analyses from both the primary STAAMP trial and the current secondary analysis were adjusted for enrollement site, and results are independent of major differences across participating centers. In order to capture those at risk for hemorrhage, we excluded patients with a shock index of ≤ 0.9, which limits the external validity of our results. Thromboelastography measurements were unable to be obtained in all patients and the comparison results are associated with missingness which limits the ability to draw appropriate conclusions. Lastly, this study was not powered to definitively conclude what was demonstrated for DELAYED group patients.

The results of this analysis adds to mounting evidence that minimizing the time between injury and TXA administration is critical for maximal outcome benefits.5, 15, 19 Capitalizing on the prehospital phase of care allows for the delivery of this life-saving treatment as close to the time of injury as possible.42 These findings underscore the multifactorial therapeutic action TXA confers in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhage. The combination of anti-fibrinolytic and anti-inflammatory effects of TXA serve as a powerful tool to combat the cascade of events triggered by endothelial damage and resulting inflammation following injury. Additionally, the findings from this study offer guidance for appropriate patient selection for prehospital TXA, with pronounced benefit in those who receive TXA within 1 hour of injury with evidence of shock.

In conclusion, we characterized a subgroup of patients that have significant benefit from prehospital TXA. Patients with shock index > 0.9 who received prehospital TXA within 1 hour of injury had lower 30-day mortality, incidence of MOF, and lower 6-hour and 24-hour blood product transfusion requirements without an increased risk of adverse effects. These current results suggest Tranexamic Acid is safe in the prehospital setting and should be administered as close to the time of injury as possible for maximal outcome benefits.

DISCUSSANT

Dr. Martin A. Schreiber

The authors have performed a secondary analysis of the STAAMP Trial. They have shown that early pre-hospital TXA (defined as within 1 hour of injury) is associated with decreased 30 day mortality, decreased incidence of MOF and decreased blood transfusion requirement while late pre-hospital TXA is not. The beneficial effects of early TXA shown here are consistent with other TXA trials. I have the following questions for the authors:

The authors have essentially combined 3 dosing groups of TXA into 1 group for this comparison with the differences being in in-hospital dosing. Is there any signal of a dosing benefit between these groups? Does in-hospital TXA appear to give any additional benefit over pre-hospital TXA? How did the authors control for different dosing regimens in their statistical analysis?

All prior studies have shown that time to dosing of TXA in trauma is critical for improving outcomes. Why did the authors choose to vary the in-hospital dosing regimen as opposed to the pre-hospital dosing regimen in light of this fact?

Despite only including patients with shock index > 0.9, Injury severity and mortality rate are low for this type of study. Do the authors believe they have adequately tested the efficacy of TXA in the high-risk hemorrhagic shock population?

The authors attest the benefits of early TXA to its anti-fibrinolytic effects, however they saw no difference in LY30 between those who received early TXA vs early placebo. How do they explain this? Should alternative mechanisms of benefit be considered?

The fact that some systems could deliver TXA earlier after an injury may be a sign that these systems provide better care overall. These systems may provide better hemorrhage control, more efficient transport and other improvements in care. The differences in outcome may not be related to TXA at all. Please comment.

I would like to congratulate the authors on another excellent study and for their leadership role in conducting critical prehospital research overall. I’d like to thank the American Surgical for the honor of discussing this paper.

Response from Dr. Shimena Li

We agree that the primary trial had 3 different dosing regimens, where the differences occurred after arrival to the trauma center. The primary comparisons in the STAAMP trial focused on the prehospital dose which was 1 gram TXA versus placebo. In the current secondary analysis we looked at the different in-hospital dosing regimens and all 3 regimens had reduced hazard for 30-day mortality in our model. As identified in preliminary subgroup analysis in the primary STAAMP trial, repeat bolus dosing (1gram in hospital bolus + 1gram infusion in addition to 1gram prehospital) was significantly associated with reduced hazard for 30-day mortality. For the purposes of this secondary analysis, we limited the comparison to prehospital dosing.

This is a great question regarding the design of the primary STAAMP trial. At the time of design, 1 gram was the only treatment dose where data existed from in-hospital treatment studies. Because of this, when the STAAMP trial was planned, the principal investigators elected to keep the prehospital dose consistent with existing literature. We are aware that a study that Dr. Schreiber was involved with used different prehospital dosing regimens.

We believe that the primary study and these secondary analysis results demonstrate that patients in shock, and significant risk of hemorrhage may benefit the most from early prehospital TXA regarding mortality. In the primary STAAMP trial less injured patients were also enrolled, and the overall STAAMP study cohort, we believe, represents the best injured cohort to verify safety and efficacy.

We agree that there were no differences found in the LY30 across the EARLY groups where the mortality benefit is demonstrated. This is likely either due to TXA working via alternative mechanisms including possibly mitigating inflammation and or endothelial injury, which could be responsible for the lower organ dysfunction seen. Importantly, there were patients who were unable to undergo TEG sampling, mostly due to severity of injury and the complex time period of the trauma bay and operating room. This missingness may limit the ability to draw definitive conclusions from the data. Alternatively, the TEG measurements occurred in the in-hospital phase of care. This may be the wrong time to characterize LY30 in a prehospital interventional study.

We agree that there may be differences across sites. TXA or placebo was available and with the prehospital providers during all flights or ground transport. We believe that the timing of intervention was most likely associated with the time it took for the patient to be under the care of the prehospital providers carrying the randomized intervention. This varied by injury mechanisms and environmental conditions. Importantly, the analyses of the primary STAAMP trial and the current secondary analysis were adjusted for site of enrollment. The current results are independent of any major differences across enrollment site.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

The primary STAAMP trial was funded by grant W81XWH 13-2-0080 from the US Army Medical Research and Material Command, Fort Detrick, Maryland. This research was supported in part by the grant 5T32HL0098036 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Li). These funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data. The preparation, review, approval and submission of the manuscript was not related to these funding sources.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grant W81XWH 13-2-0080 from the US Army Medical Research and Material Command, Fort Detrick, Maryland and grant 5T32HL0098036 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma 2006; 60(6 Suppl):S3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacLeod JB, Lynn M, McKenney MG, et al. Early coagulopathy predicts mortality in trauma. J Trauma 2003; 55(1):39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JB, Cohen MJ, Minei JP, et al. Characterization of acute coagulopathy and sexual dimorphism after injury: females and coagulopathy just do not mix. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73(6):1395–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niles SE, McLaughlin DF, Perkins JG, et al. Increased mortality associated with the early coagulopathy of trauma in combat casualties. J Trauma 2008; 64(6):1459–1463; discussion 1463–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, et al. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 313(5):471–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tisherman SA, Schmicker RH, Brasel KJ, et al. Detailed Description of All Deaths in Both the Shock and Traumatic Brain Injury Hypertonic Saline Trials of the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium. Annals of surgery 2015; 261(3):586–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health S, Its Translation to the Civilian S, Board on Health Sciences P, et al. In: Berwick D, Downey A, Cornett E, eds. A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2016 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet (British edition) 2010; 376(9734):23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison JJ, Dubose JJ, Rasmussen TE, et al. Military Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation (MATTERs) Study. Arch Surg 2012; 147(2):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neeki MM, Dong F, Toy J, et al. Tranexamic Acid in Civilian Trauma Care in the California Prehospital Antifibrinolytic Therapy Study. West J Emerg Med 2018; 19(6):977–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet (British edition) 2019; 394(10210):1713–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rappold JF, Pusateri AE. Tranexamic acid in remote damage control resuscitation. Transfusion 2013; 53 Suppl 1:96S–99S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holcomb JB, del Junco DJ, Fox EE, et al. The prospective, observational, multicenter, major trauma transfusion (PROMMTT) study: comparative effectiveness of a time-varying treatment with competing risks. JAMA Surg 2013; 148(2):127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts I, Shakur H, Afolabi A, et al. The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet (British edition) 2011; 377(9771):1096–1101.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sperry JL, Guyette FX, Brown JB, et al. Prehospital Plasma during Air Medical Transport in Trauma Patients at Risk for Hemorrhagic Shock. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(4):315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruen DS, Guyette FX, Brown JB, et al. Association of Prehospital Plasma With Survival in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Secondary Analysis of the PAMPer Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3(10):e2016869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson TN, Hinson HE, Dewey EN, et al. Early Tranexamic Acid Administration After Traumatic Brain Injury Is Associated With Reduced Syndecan-1 and Angiopoietin-2 in Patients With Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2020; 35(5):317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyette FX, Brown JB, Zenati MS, et al. Tranexamic Acid During Prehospital Transport in Patients at Risk for Hemorrhage After Injury: A Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowell SE, Meier EN, McKnight B, et al. Effect of Out-of-Hospital Tranexamic Acid vs Placebo on 6-Month Functional Neurologic Outcomes in Patients With Moderate or Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA 2020; 324(10):961–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152(11):726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauaia A, Moore EE, Johnson JL, et al. Validation of postinjury multiple organ failure scores. Shock 2009; 31(5):438–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reitz KM, Moore HB, Guyette FX, et al. Prehospital plasma in injured patients is associated with survival principally in blunt injury: Results from two randomized prehospital plasma trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020; 88(1):33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional Hazards Tests and Diagnostics Based on Weighted Residuals. Biometrika 1994; 81(3):515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Reinikainen J, Adeleke KA, et al. Time-varying covariates and coefficients in Cox regression models. Ann Transl Med 2018; 6(7):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gronnesby JK, Borgan O. A method for checking regression models in survival analysis based on the risk score. Lifetime Data Anal 1996; 2(4):315–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cannon CM, Braxton CC, Kling-Smith M, et al. Utility of the shock index in predicting mortality in traumatically injured patients. J Trauma 2009; 67(6):1426–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olaussen A, Blackburn T, Mitra B, et al. Review article: shock index for prediction of critical bleeding post-trauma: a systematic review. Emerg Med Australas 2014; 26(3):223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole E, Davenport R, Willett K, et al. Tranexamic acid use in severely injured civilian patients and the effects on outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg 2015; 261(2):390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts I, Edwards P, Prieto D, et al. Tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploration of benefits and harms. Trials 2017; 18(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brohi K, Singh J, Heron M, et al. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma 2003; 54(6):1127–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Davenport RA. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: mechanism, identification and effect. Curr Opin Crit Care 2007; 13(6):680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, et al. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg 2007; 245(5):812–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Floccard B, Rugeri L, Faure A, et al. Early coagulopathy in trauma patients: an on-scene and hospital admission study. Injury 2012; 43(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stansfield R, Morris D, Jesulola E. The Use of Tranexamic Acid (TXA) for the Management of Hemorrhage in Trauma Patients in the Prehospital Environment: Literature Review and Descriptive Analysis of Principal Themes. Shock 2020; 53(3):277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore FA, Sauaia A, Moore EE, et al. Postinjury multiple organ failure: a bimodal phenomenon. J Trauma 1996; 40(4):501–510; discussion 510–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durham RM, Moran JJ, Mazuski JE, et al. Multiple organ failure in trauma patients. J Trauma 2003; 55(4):608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu X, Benov A, Darlington DN, et al. Effect of tranexamic acid administration on acute traumatic coagulopathy in rats with polytrauma and hemorrhage. PLoS One 2019; 14(10):e0223406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wafaisade A, Lefering R, Bouillon B, et al. Prehospital administration of tranexamic acid in trauma patients. Crit Care 2016; 20(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiraishi A, Kushimoto S, Otomo Y, et al. Effectiveness of early administration of tranexamic acid in patients with severe trauma. Br J Surg 2017; 104(6):710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunze-Szikszay N, Krack LA, Wildenauer P, et al. The pre-hospital administration of tranexamic acid to patients with multiple injuries and its effects on rotational thrombelastometry: a prospective observational study in pre-hospital emergency medicine. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2016; 24(1):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theusinger OM, Baulig W, Seifert B, et al. Changes in coagulation in standard laboratory tests and ROTEM in trauma patients between on-scene and arrival in the emergency department. Anesth Analg 2015; 120(3):627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ausset S, Glassberg E, Nadler R, et al. Tranexamic acid as part of remote damage-control resuscitation in the prehospital setting: A critical appraisal of the medical literature and available alternatives. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015; 78(6 Suppl 1):S70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]