Delirium occurs in up to 50% of all critically ill adults (1). This common ICU phenomenon is associated with a substantial burden to patients and families and has serious ICU and post-ICU sequelae (1). Mortality is an important concern among ICU survivors and their families (2). The relationship between ICU delirium and post-ICU mortality is unclear (3). Cohort studies evaluating the association between delirium and mortality over 1 to 12 months of follow up have discordant results (1, 3, 4). Among these studies, there is important variability in ICU patient populations, methods of delirium detection and evaluation (e.g. incidence vs. prevalence, duration, severity), and how potential confounding has been considered.

In this issue of the Journal, Fiest and colleagues (pp. 412–420) make an important contribution via their population-based study evaluating the association of ICU delirium and mortality over up to 2.5 years of follow up in 12,137 adults consecutively admitted >24 hours to any of the 14 medical-surgical ICUs in the province of Alberta, Canada (population: 4.4 million) (5). This study also explored the association between ICU delirium and subsequent hospital readmissions and emergency department visits, including mortality as a competing risk. Using five province-wide databases, the authors evaluated comprehensive data, including patient demographics, ICU clinical variables, mortality, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits. Using propensity scoring, the “ICU delirium” and “no ICU delirium” patient cohorts were matched on five baseline variables and four ICU variables. The statistical methods considered time dependence of the outcome measures with delirium, patient clustering within ICUs, and different methods of evaluating delirium (e.g., duration and severity).

Among the 5,936 propensity-matched critically ill adults who survived to hospital discharge, the incidence of delirium in the ICU was associated with greater mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–1.92) up to 30 days after hospital discharge (5). Beyond 90 days after hospital discharge, a significant association was not found (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91–1.16). During the 2.5-year study period, delirium occurrence was associated with an increased risk for emergency department visits, hospital readmissions, or death after the index hospitalization (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.07–1.17).

These results are an important building block in better understanding the long-term outcomes of ICU delirium and in reflecting on clinical care in the ICU (5). The survivorship experience is a critical concern for ICU patients and families (6). The incidence and duration of ICU delirium may be a potentially modifiable risk factor for post–intensive care syndrome (6). Notably, a longer duration of delirium in the ICU is independently associated with worse global cognition at the 3- and 12-month follow up (7). Although not evaluated in the paper by Fiest and colleagues (5), multicomponent ICU quality-improvement interventions (e.g., the ABCDEF bundle), supported by the Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep clinical practice guidelines (3), are associated with reductions in ICU delirium, hospital mortality, and ICU readmissions (8). However, the impact of such interventions on long-term mortality and patient outcomes requires more evaluation.

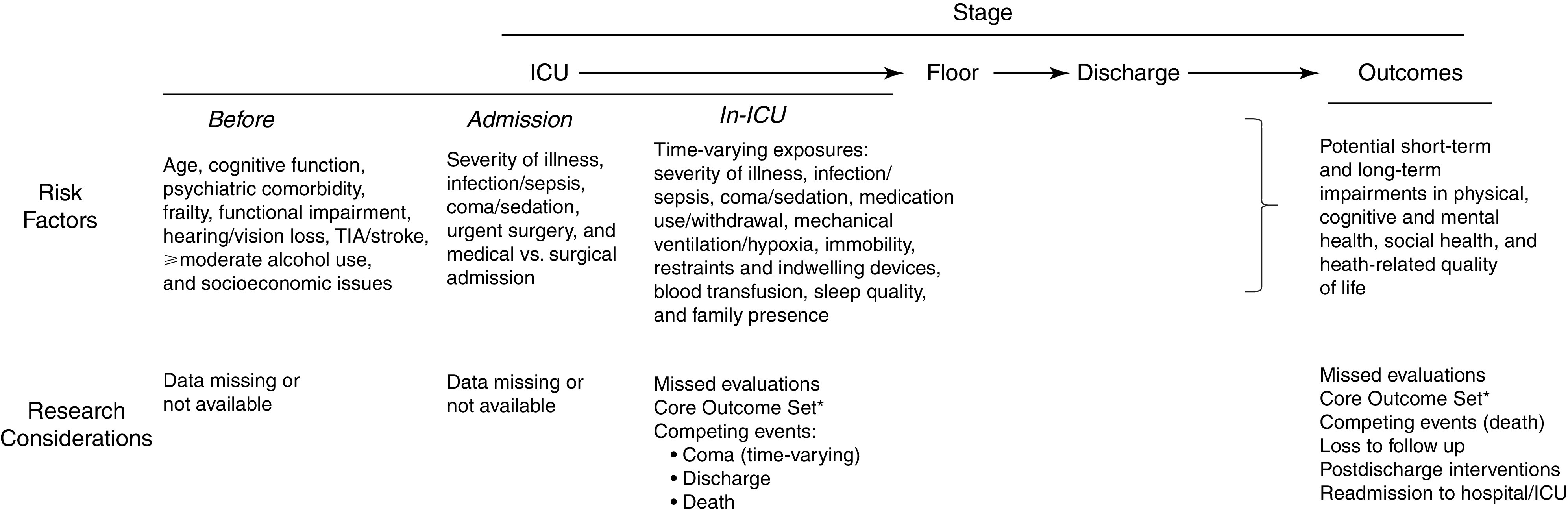

To further build on the analysis by Fiest and colleagues (5), future studies should evaluate interrelationships between ICU sedation status (including coma), sedative choice, and delirium occurrence and their effect on post-ICU mortality and patient outcomes. Herein, we provide some recommendations for future research in this area. First, explicit consideration of a sedative-induced coma is important given its association with mortality and given that coma is a competing risk in evaluating delirium in the ICU (3, 4, 9). Second, an evaluation of specific classes of medications in the ICU (e.g., benzodiazepines, propofol, dexmedetomidine, and opioids) is important to better understand associations of delirium with post-ICU mortality and patient outcomes (3, 10, 11). Third, given that critically ill adults are frequently discharged on psychoactive medications, further exploration of associations of post-ICU medications and patient mortality and outcomes is recommended (12). Fourth, given that preexisting frailty and cognitive function are important predictors of ICU delirium and associated with increased mortality and deleterious post-ICU patient outcomes (13, 14), these baseline variables are important to evaluate in future research. Finally, given that post-ICU exposures (e.g., rehabilitation services and hospital readmissions) and variability in patient recovery trajectories impact survivors’ post-ICU outcomes, their consideration is warranted. Figure 1 proposes key baseline, ICU, and post-ICU risk factors and research considerations for delirium and long-term outcome studies.

Figure 1.

Risk factors and research considerations for delirium and long-term outcomes studies. Various risk factors and research considerations may influence reported associations between in-hospital incidence, duration, and/or severity and postdischarge outcomes. Readmission to the ICU or hospital may further negatively impact delirium and long-term patient outcomes. *Two separate Core Outcome Sets exist for research on delirium in the ICU and on long-term outcomes after acute respiratory failure (15, 16). Please also see https://www.improvelto.com/. TIA = transient ischemic attack.

In conclusion, via this new population-based retrospective study (5), important progress has been made in better understanding the association of delirium with post-ICU mortality and healthcare resource use. To continue advancing the field, future prospective studies should embrace a recent Core Outcome Set for ICU delirium research that recommends inclusion of seven outcomes: delirium occurrence (prevalence or incidence), delirium severity, time to delirium resolution, health-related quality of life, emotional distress, cognition, and mortality (15). Future prospective studies also should consider addressing key knowledge gaps via evaluating established delirium risk factors, post-ICU mortality, and patient-important outcomes while taking into account the complexities of competing risks in assessing delirium and long-term outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Bhavna Seth, M.D., and Babar Khan, M.D., M.S., for their insights regarding the editorial and its accompanying figure.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institute on Aging R33HL23452 (J.W.D.) and R24AG054259 (D.M.N.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202104-0910ED on June 29, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB, Nagaraja N, Yenokyan G, Damluji A, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ . 2015;350:h2538. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Davis WE, Parker A, Friedman LA, Colantuoni E, et al. Perspectives of survivors, families and researchers on key outcomes for research in acute respiratory failure. Thorax . 2018;73:7–12. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med . 2018;46:e825–e873. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duprey MS, van den Boogaard M, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P, Briesacher BA, Saczynski JS, et al. Association between incident delirium and 28- and 90-day mortality in critically ill adults: a secondary analysis. Crit Care . 2020;24:161. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02879-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiest KM, Soo A, Hee Lee C, Niven DJ, Ely EW, Doig CJ, et al. Long-term outcomes in ICU patients with delirium: a population-based cohort study Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021204412–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dinglas VD, Faraone LN, Needham DM. Understanding patient-important outcomes after critical illness: a synthesis of recent qualitative, empirical, and consensus-related studies. Curr Opin Crit Care . 2018;24:401–409. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med . 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, et al. Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Crit Care Med . 2019;47:3–14. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colantuoni E, Dinglas VD, Ely EW, Hopkins RO, Needham DM. Statistical methods for evaluating delirium in the ICU. Lancet Respir Med . 2016;4:534–536. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hughes C, Mailloux P, Devlin JW, Swan JT, Sanders RD, Anzueto A, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs. propofol for sedation in mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis. New Engl J Med. 2021;384:1424–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duprey MS, Dijkstra-Kersten SMA, Zaal IJ, Briesacher BA, Saczynski JS, Griffith JL, et al. Opioid use increases the risk of delirium in critically ill adults independent of pain. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202010-3794OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown SM, Bose S, Banner-Goodspeed V, Beesley SJ, Dinglas VD, Hopkins RO, et al. Addressing Post Intensive Care Syndrome 01 (APICS-01) study team. Approaches to addressing post-intensive care syndrome among intensive care unit survivors. A narrative review. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2019;16:947–956. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-913FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanchez D, Brennan K, Al Sayfe M, Shunker SA, Bogdanowski T, Hedges S, et al. Frailty, delirium and hospital mortality of older adults admitted to intensive care: the Delirium (Deli) in ICU study. Crit Care. 2020;24:609. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03318-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrante LE, Murphy TE, Leo-Summers LS, Gahbauer EA, Pisani MA, Gill TM. The combined effects of frailty and cognitive impairment on post-ICU disability among older ICU survivors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;200:107–110. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1144LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rose L, Burry L, Agar M, Campbell NL, Clarke M, Lee J, et al. Del-COrS Group. A core outcome set for research evaluating interventions to prevent and/or treat delirium in critically ill adults: an international consensus study (Del-COrS) Crit Care Med . 2021 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Friedman LA, Bingham CO, III, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors: an international modified delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]