Abstract

Background:

Prostate cancer (PC) is one of the most abundant cancers among men, and In Iran, has been responsible for 6% of all deaths from cancer in men. NUF2 and GMNN genes are considered as loci of susceptibility to tumorigenesis in humans. Alterations in expression of these genes have been reported in various malignancies. The aim of our study was to test whether different NUF2 and GMNN expression levels are associated with PC incidence and hence, might be considered as new molecular tools for PC screening.

Methods:

Biopsy samples from 40 PC patients and 41 healthy Iranian men were used to determine the relative gene expression. After RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis, samples were analyzed using TaqMan Quantitative Real time PCR. Patients’ background information, included smoking habits and family histories of PC, were recorded. Stages and grades of their PC were classified by the TNM tumor, node, metastasis (TMN) staging system based on standard guidelines.

Results:

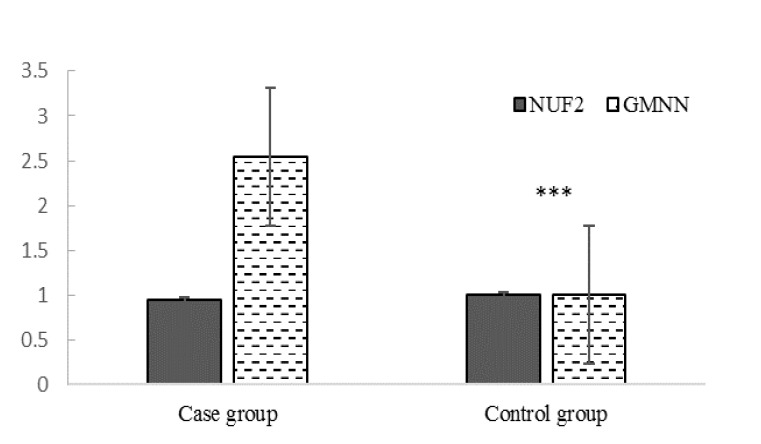

NUF2 expression did not significantly differ between the groups, while GMNN expression was significantly greater in the PC specimens than in the controls.

Conclusion:

Regarding the significant role of GMNN in various tumor phenotypes, and its importance in PC progression, the alteration in GMNN expression in PC samples vs. controls indicate that the genetic profiling of this cancer might be considered to personalize therapy for each patient in the future.

Key Words: Family history, Geminin (GMNN), Tumor staging, NUF2, Prostate cancer

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, and expected to increase rapidly as populations grow (1, 2). In 2018, there were an estimated 18.1 million new cancer cases (17.0 million except for nonmelanoma skin cancer) and 9.6 million cancer deaths (9.5 million except for nonmelanoma skin cancer). Prostate cancer(PC) is the second most frequent malignancy after lung cancer in men worldwide, accounting for 1,276,106 new cases and 358,989 deaths (3.8% of all deaths caused by cancer in men) (3). The PC incidence rate varies greatly in different parts of the world; the highest rate was observed in North America, and the lowest in South Asia. The incident rate correlates strongly with increasing age, with the average age at the time of diagnosis being 66 years (4). The PC incidence was less in Iran than in the other parts of the world, with an age-standardized rate (ASR) of 9.11/100,000 (5).

The key factor to reduce the PC mortality rate is early detection and improvement in therapeutic strategies. In many cases the late stages of the cancer are resistant to routine treatments (6); therefore, early detection, and more importantly prediction, are of great interest. Prostate cancer is highly correlated with various risk factors including age, family history, environmental exposures (7), and genetic and epigenetic alterations (8). Despite efforts to develop multiple risk measurement systems for diagnosis at the earliest cancer stages, all failed in PC prediction (9). Long-term survival is high in localized PC; however, metastatic PC remains largely incurable even after intensive multimodal therapy. The lethality of advanced disease is mostly driven by the lack of therapeutic regimens for generating durable responses because of the extreme level of tumor heterogeneity on the genetic and cell biological aspects (10).

NUF2 encodes the NUF2 protein, a kinetochore protein that forms a stable complex with HEC1, SPC24, and SPC25, named the NDC80 complex. In mitosis, NUF2, as well as other components of the NDC80 complex, mainly contribute to kinetochore-microtubule attachment (11). Current evidence has shown that human NUF2 potentially interacts with centromere-associated protein E and is essential for stable spindle kinetochore-microtubule attachment (12, 13). Evidence showed that down regulation of NUF2 blocked kinetochore-microtubule attachment and induced mitotic cell death in HeLa cells (11), and the NUF2 CH domain plays a key role in NUF2-mediated kinetochore-microtubule attachment (14). NUF2 was first identified as an overexpressed protein in various lung cancer histological types through genome-wide expression analysis and named as cell division cycle associated 1 (CDCA1) (15). The activated form of NUF2 is involved in carcinogenesis and corresponds with patients’ prognoses. NUF2 was reported as a novel cancer-testis antigen that was overexpressed in multiple human cancers including lung, cholangiocellular, renal cell, and urinary bladder cancers. It was considered as a perfect tumor-associated antigen for both cancer diagnosis and immunotherapy (16). Furthermore, recent findings revealed that knockdown of NUF2 through siRNA resulted in cell proliferation inhibition and apoptosis induction in different cancer types including colorectal and gastric cancers and osteosarcoma Saos-2 cells (17-19). These reports demonstrate the possible role of NUF2 in human cancer development.

GMNN, located on chromosome 6, encodes the geminin protein (GMNN) (molecular weight, 23565 Da), which is critical for origin licensing. GMNN was first identified as a general inhibitor of DNA replication in Xenopus laevis egg extracts with no further knowledge of its function in humans (16). Later, GMNN was reported as an inhibitor of Cdc10-dependent transcript (Cdt1) (20). A conformational change between GMNN-Cdt1 heterotrimer and heterohexamer complex is responsible for licensing or inhibition of DNA replication. GMNN inhibits Cdt1-mediated minichromosome maintenance helicases (MCM) loading onto the chromatin-bound origin recognition complex (ORC), which results in the inhibition of pre-replication complex assembly. GMNN regulates DNA replication by binding directly to Cdt, affecting its stability and activity, and is involved in different developmental stages through interaction with various proteins (21). Furthermore, GMNN expression is highly associated with cancer pathophysiology and development (22).

According to the roles of NUF2 and GMNN in cancer development the goal of this study was to compare the expression levels of these genes in specimens obtained from PC patients at various stages with those from healthy controls to determine whether these genes can be applied as factors to stage PC.

Materials and Methods

Case selection and tissue sampling

Forty PC patients admitted to Shahid Akbar Abadi Hospital (Tehran, Iran) were selected randomly from February to December 2018. The biopsy test results verified the cancer type; no age limitation was applied during cases selection. Smoking habits and familial history of PC were documented and the PC severity for each patient was measured using the tumor, node, and metastasis (TMN) staging system. The control group consisted of 41 healthy volunteers with no history of malignant or any urological disease.

Sample preparation and RNA extraction

Prostate tissue samples were stored and maintained in liquid nitrogen until RNA extraction. A Super RNA Extraction Kit for Tissue & Culture Cells (Favorgen Biotech Corp, Taiwan) was used to extract the total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The optical density (OD) of each sample at was measured at 260 and 280 nm (Ultrospec 2100 (Biochrom, USA)) and used as criteria to determine the amount of RNA in each sample. RNA was reverse transcribed in 20 µl reaction mixtures containing: first strand buffer, 200 units of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, 20 units of RNasin, 10 mM DTT, 4.75 µM random hexamers, and 500 µM deoxynucleotides (all from Promega, Madison, WI) at 37 °C for 1 hr. Finally, the resultant mixture was heated at 95 °C for 5 min before storage at -20 °C.

Primers and probes design

The TaqMan primers and probes for the SEC14L1, TCEB1 and FAM72b genes were designed with the help of Primer Express software (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). To reduce the DNA contamination, primers were designed to span at least one intron of the respective genomic sequence. To label the TaqMan probes, the dye FAM and the quencher dye TAMRA, with emission wavelengths of 518 and 582 nm, were used at the 5' and 3' ends, respectively. The 3' end of the probe was phosphorylated to prevent extension during PCR. These sequences were checked for their specificity via the Check-Probe function of the Ribosomal Database Project software package and the BLAST database search program. Gene-specific primers were used according to the following sequences: human GMNN, forward primer: 5′-CGGGCGAGCGGAGTTAGCAG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-TGGCTGCAGCACCTCGCAAA-3′; and human NUF2, forward primer: 5′-TACCATTCAGCAATTTAGTTACT-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-TAGAATATCAGCAGTCTCAAAG-3′.

TaqMan real-time PCR

Real-time TaqMan qPCR amplification was performed using a Rotor-Gene 6000 real-time PCR cycler (Qiagen Corbett, Hilden, Germany) with the following method: one step at 95 °C for 5 min, and 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 sec, and 60 °C for 30 sec. For each step, 20 ml of the reaction mixture was used containing: 0.4 ml of forward primer, 0.4 ml of reverse primer, 0.4 ml of TaqMan probe, 12 ml of Probe 2x Taq (Probe qPCR) Master Mix (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), 1 ml of template cDNA, and 5.8 ml of sterilized ultra-pure water. Negative controls included all components of the reaction mixture except for the template cDNA. The negative controls had no detected amplified DNA products and were used during the analysis. The real-time PCRs were performed in triplicate and the data are presented as the mean values of the analysis.

Statistical analysis

In this study subjects’ data were obtained though questionnaires and entered into SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago) for analysis. The data are presented as means±SDs. Demographic results were collected from both groups and interpreted according to frequency. Subjects were divided into four age groups as follows: 1) age ≤45, 2) 45 <age ≤54, 3) 54< age ≤63, and 4) age >63. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the normal distribution of all data and the Mann-Whitney test was used to evaluate oncogene differences between groups. The chi-square test (X2) was used to determine whether age, smoking, or family history affected PC risk. Eventually, the eta (η) correlation ratio was performed to examine the relationship between the different oncogenes and the stage of PC. The level of statistical significance was set at p≤ 0.05.

Results

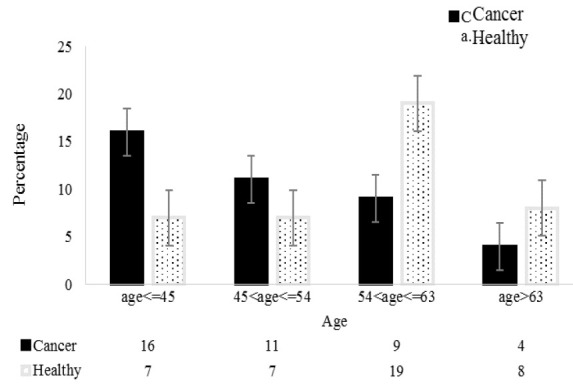

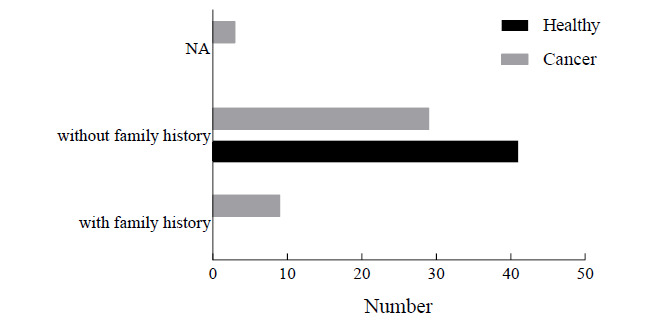

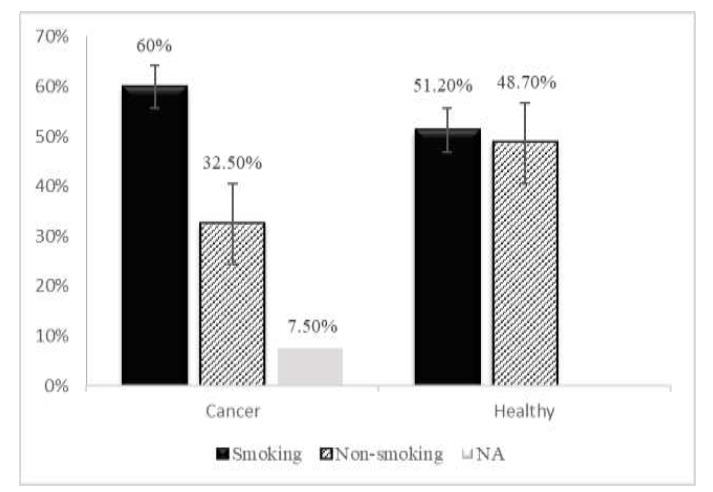

Statistics revealed no significant differences in the ages of patients and healthy controls, which ranged from 25 to 88 (48.70±15.32) and 23 to 89 (53.63±13.35) years, respectively. As indicated by the X2 test, the incidence of PC differed significantly between age groups (X2= 9.30; p= 0.026). The greatest PC prevalence was in patients≤ 45 years (16/23) and the least in patients 54<age≤63 years (9/28) (Fig. 1). In the control group, no family history of PC was recorded, while among PC patients, 9/37 (24.3%) had family histories of PC (Fig. 2). Regarding smoking, 60 and 51.2% of PC patients and healthy controls smoked, respectively (Fig. 3). Analysis of data by the X2 test showed that family history of PC significantly affected PC prevalence (X2= 14.43; p= 0.001), while smoking had no significant effect on PC prevalence (X2= 4.67; p= 0.097).

Fig. 1.

The number of PC patients and healthy controls in the four age groups.

Fig. 2.

The numbers of controls and PC patients without and with family histories of PC; NA: not applicable.

Fig. 3.

Percentages of prostate cancer patients and healthy controls who smoked; NA: not applicable.

The patients’ PC stages are presented in Table 1. The T2N1M0 stage was the most frequent (47.5 %) among the patients, whereas T1N0M0, T1N1M1, and T4N1M1 were the least frequent (2.5%). No significant correlation was observed between the PC stage and either smoking habits or family history of PC.

Table 1.

The frequency of different TNM staging system of prostate cancer and the corresponding relationship with family history and smoking.

| TNM staging system (n= 40) | Frequency (%) | Smoking habit | Family history | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | NA (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | NA (%) | ||

| T1N0M0 | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | - | - | - | 1 (2.5) | - |

| T1N1M1 | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | - | - | 1 (2.5) | - | - |

| T2N1M0 | 19 (47.5) | 11 (27.5) | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (7.5) | 15 (37.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| T2N1M1 | 4 (10) | - | 4 (10) | - | - | 4 (10) | - |

| T2N2M1 | 7 (17.5) | 4 (10) | 3 (7.5) | - | 2 (5) | 4 (10) | 1 (2.5) |

| T3N1M1 | 2 (5) | - | 2 (5) | - | 2 (5) | - | - |

| T4N1M1 | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | - | - | - | 1 (2.5) | - |

| NA | 5 (12.5) | 2 (5) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (2.5) |

T0: In this case, no tumor was found in the prostate tissue

Regarding the importance of NUF2 and GMNN role in malignancies, the mRNA level of these genes from 40 PC patients and 41 healthy controls were measured using qRT-PCR. NUF2 expression was nearly identical in the two groups; however, GMNN expression was significantly greater in PC tissue samples than in those from the healthy group (2.54±0.290 vs. 1.211±0.117, p< 0.0005) (Fig. 4). Finally, data analysis by eta (η) revealed that the association between the PC stage and NUF2 and GMNN expression was medium and weak, respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Relative expression of NUF2 and GMNN in biopsies from cancerous and healthy prostates.

Table 2.

Association of NUF2 and GMNN expression level with the stage of PC.

| Variable | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Stage Dependence | 0.883 | Medium association between the variables |

| NUF2 Dependence | 0.453 | |

| Stage Dependence | 1.000 | Weak association between the variables |

| GMNN Dependence | 0.356 |

Discussion

The current clinical tools for PC progress evaluation, including the pathologic grade and serum prostate-specific (PSA) levels, provide a significant level of discrimination in the identification of those at the highest and lower risk of more aggressive disease (23). For many, this information does not provide a solid picture to determine the most appropriate clinical course (24). Investigating genetic alterations is a new approach to find new targets for tumor therapies, yet few oncogenes have been discovered in prostate carcinogenesis (25, 26). The current study aimed to study two candidate genes suggested to be involved in cancer progression. NUF2 is reported to stabilize microtubule attachment as part of a linker between the kinetochore and tubulin subunits of the spindle, and depletion of NUF2 could induce defective kinetochore attachment and spindle checkpoint activation leading to mitotic cells death (27). NUF2 is a member of cancer/testis (CT) proteins, a group of proteins normally restricted in adult testes of adults but aberrantly expressed in several types of cancers (28). These antigens are highly immunogenic in cancer patients with an extremely tissue-restricted expression. Prostate cancer is considered a moderate CT gene expressor, with 6/20 (30%) CT transcripts having expression frequencies> 20% (29). In our study, NUF2 expression was not significantly different between PC patients and controls, in contrast with results of Shiraishi et al., who reported an increase in NUF2 expression in PC patients following radical prostatectomy (29). Moreover, NUF2 expression is reported to be altered in a stage-specific manner in prostate carcinogenesis, making it an excellent candidate for cancer staging evaluation (30).

Chromosomal DNA duplication is an essential process for all organisms and needs to be tightly regulated to preserve genomic integrity. GMNN is an origin licensing protein with a dual role in the regulation of DNA replication: first, it inhibits replication factor CDT1 activity during the G2 phase of the cell cycle, and second, it promotes its own accumulation at the G2/M transition. Thereby, GMNN prevents DNA re-replication during G2 and ensures that DNA replication is efficiently executed in the next S phase (31). In 2002, GMNN was suggested as a marker for cell proliferation in normal tissues and malignancies (32). Furthermore, its ablation resulted in re-replication and DNA damage and enhanced tumorigenesis through increasing genomic instability (33). GMNN overexpression was reported in various cancer tissues including PC (34-36). Differential GMNN expression is associated with various cancer types, and its expression correlate significantly with nuclear grade and poor prognosis in breast cancer patients (34). Alterations in GMNN expression were reported in various cancer tissues (34-36) and findings showed that its overexpression correlated with recruitment and crosstalk with mesenchymal stem cells resulted in enhanced aggressiveness in breast cancer (37), however, Bánfi et al (40) found no significant difference in GMNN expression in samples from androgen-sensitive vs androgen-refractory PC samples. In our study, GMNN expression was significantly greater in PC patients than in controls. It has been proposed that GMNN could be a valuable marker for estimation of tumor aggressiveness and clinical outcome in cancer patients (20, 38, 39). Further studies are required to evaluate GMNN as a PC prediction marker and/or therapy target.

Our results revealed that NUF2 expression was not significantly different, while GMNN expression was significantly greater, in PC tissues, which was associated with progression and metastasis in PC patients, than in controls. GMNN might be a good candidate for consideration in future studies to find prognostic markers in selection of tumor therapy or the population at risk for cancer progression.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Islamic Azad University for general support. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends—an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):16, 27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosseini M-S, Hosseini F, Ahmadi A, Mozafari M, Amjadi I. Antiproliferative Activity of Hypericum perforatum, Achillea millefolium, and Aloe vera in Interaction with the Prostatic Activity of CD82. Rep Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;8(3):260, 268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394, 424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly SP, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Cook MB. Past, current, and future incidence rates and burden of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4(1):121, 127. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassanipour S, Fathalipour M, Salehiniya H. The incidence of prostate cancer in Iran:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Int. 2018;6(2):41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pagliuca M, Buonerba C, Fizazi K, Di Lorenzo G. The Evolving Systemic Treatment Landscape for Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer. Drugs. 2019;79(4):381–400. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-1060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha Chung B, Horie S, Chiong E. The incidence, mortality, and risk factors of prostate cancer in Asian men. Prostate Int. 2019;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vieira-Silva TS, Monteiro-Reis S, Barros-Silva D, Ramalho-Carvalho J, Graça I, Carneiro I, et al. Histone variant MacroH2A1 is downregulated in prostate cancer and influences malignant cell phenotype. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:112. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0835-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell. 2015;163(4):1011–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang G, Zhao D, Spring DJ, DePinho RA. Genetics and biology of prostate cancer. Dev. 2018;32(17-18):1105–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.315739.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLuca JG, Moree B, Hickey JM, Kilmartin JV, Salmon E. hNuf2 inhibition blocks stable kinetochore–microtubule attachment and induces mitotic cell death in HeLa cells. Cell Biology. 2002;159(4):549–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu D, Ding X, Du J, Cai X, Huang Y, Ward T, et al. Human NUF2 interacts with centromere-associated protein E and is essential for a stable spindle microtubule-kinetochore attachment. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(29):21415–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brusini L, D'archivio S, McDonald J, Wickstead B. Ndc80/ Nuf2-like protein KKIP1 connects a stable kinetoplastid outer kinetochore complex to the inner kinetochore and responds to metaphase tension. BioRxiv. 2019:764829. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundin LJ, Guimaraes GJ, DeLuca JG. The NDC80 complex proteins Nuf2 and Hec1 make distinct contributions to kinetochore–microtubule attachment in mitosis. Molecular Biology of The Cell. 2011;22(6):759–68. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayama S, Daigo Y, Kato T, Ishikawa N, Yamabuki T, Miyamoto M, et al. Activation of CDCA1-KNTC2, members of centromere protein complex, involved in pulmonary carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 2006;66(21):10339–48. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harao M, Hirata S, Irie A, Senju S, Nakatsura T, Komori H, et al. HLA-A2-restricted CTL epitopes of a novel lung cancer-associated cancer testis antigen, cell division cycle associated 1, can induce tumor-reactive CTL. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;123(11):2616–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko N, Miura K, Gu Z, Karasawa H, Ohnuma S, Sasaki H, et al. siRNA-mediated knockdown against CDCA1 and KNTC2, both frequently overexpressed in colorectal and gastric cancers, suppresses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. . 2009;390(4):1235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu H, Shao L. Silencing of NUF2 inhibits proliferation of human osteosarcoma Saos-2 cells. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2016;20(6):1071–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu P, Shangguan J, Zhang L, editors. Downregulation of NUF2 inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis by regulating lncRNA AF339813. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 2015;8(3):2638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haruki T, Shomori K, Hamamoto Y, Taniguchi Y, Nakamura H, Ito H. Geminin expression in small lung adenocarcinomas: implication of prognostic significance. Lung Cancer. 2011;71(3):356–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fame RM, Lehtinen MK. Sister, Sister: Ependymal Cells and Adult Neural Stem Cells Are Separated at Birth by Geminin Family Members. Neuron. 2019;102(2):278–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Cai M, Gong Z, Zhang B, Li Y, Guan L, et al. Geminin facilitates FoxO3 deacetylation to promote breast cancer cell metastasis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2017;127(6):2159–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI90077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter HB. Differentiation of lethal and non lethal prostate cancer: PSA and PSA isoforms and kinetics. Asian Journal of Andrology. 2012;14(3):355. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen CT, Kattan MW. Formalized prediction of clinically significant prostate cancer: is it possible? Asian Journal of Andrology. 2012;14(3):349. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24(18):1967–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.1965810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong JT. Prevalent mutations in prostate cancer. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2006;97(3):433–47. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Q, Dai S-J, Li H, Dong L, Peng Y-P. Silencing of NUF2 inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(20):8623–9. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.20.8623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scanlan MJ, Simpson A, Old LJ. The cancer/testis genes: review, standardization, and commentary. Cancer Immune. 2004;4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiraishi T, Terada N, Zeng Y, Suyama T, Luo J, Trock B, et al. Cancer/Testis antigens as potential predictors of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy. J Transl Med. 2011;9:153. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi S, Shiraishi T, Miles N, Trock BJ, Kulkarni P, Getzenberg RH. Nanowire analysis of cancer-testis antigens as biomarkers of aggressive prostate cancer. Urology. 2015;85(3):704.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballabeni A, Zamponi R, Moore JK, Helin K, Kirschner MW. Geminin deploys multiple mechanisms to regulate Cdt1 before cell division thus ensuring the proper execution of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(10):E2848–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310677110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wohlschlegel JA, Kutok JL, Weng AP, Dutta A. Expression of geminin as a marker of cell proliferation in normal tissues and malignancies. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(1):267–73. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Champeris Tsaniras S, Villiou M, Giannou AD, Nikou S, Petropoulos M, Pateras IS, et al. Geminin ablation in vivo enhances tumorigenesis through increased genomic instability. J Pathol. 2018;246(2):134–140. doi: 10.1002/path.5128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yagi T, Inoue N, Yanai A, Murase K, Imamura M, Miyagawa Y, et al. Prognostic significance of geminin expression levels in Ki67-high subset of estrogen receptor-positive and HER2-negative breast cancers. Breast Cancer. 2016;23(2):224–30. doi: 10.1007/s12282-014-0556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing Y, Wang C, Wu J. Expression of geminin, p16, and Ki67 in cervical intraepithelial neoplasm and normal tissues. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(26):e7302. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vargas PA, Cheng Y, Barrett AW, Craig GT, Speight PM. Expression of Mcm-2, Ki-67 and geminin in benign and malignant salivary gland tumours. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37(5):309–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ananthula S, Sinha A, El Gassim M, Batth S, Marshall Jr GD, Gardner LH, et al. Geminin overexpression-dependent recruitment and crosstalk with mesenchymal stem cells enhance aggressiveness in triple negative breast cancers. Oncotarget. 2016;7(15):20869–89. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shomori K, Nishihara K, Tamura T, Tatebe S, Horie Y, Nosaka K, et al. Geminin, Ki67, and minichromosome maintenance 2 in gastric hyperplastic polyps, adenomas, and intestinal-type carcinomas: pathobiological significance. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13(3):177–85. doi: 10.1007/s10120-010-0558-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Bonito M, Cantile M, Collina F, Scognamiglio G, Cerrone M, La Mantia E, et al. Overexpression of cell cycle progression inhibitor geminin is associated with tumor stem-like phenotype of triple-negative breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(2):162–71. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bánfi G, Teleki I, Nyirády P, Keszthelyi A, Romics I, Fintha A, et al. Changes of protein expression in prostate cancer having lost its androgen sensitivity. International Urology and Nephrology. 2015;47(7):1149–54. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-0985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]