Abstract

Resveratrol (RSV) and metformin (MET) play a role in the treatment of diabetes; however, the mechanisms through which they mediate insulin resistance by regulating long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) remain unknown. The present study was conducted to determine whether RSV and MET can improve insulin resistance in the livers of high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice by regulating lncRNAs. C57BL/6J mice were fed a HFD for 8 weeks to establish a model of insulin resistance. The mice were subsequently treated with RSV or MET for 8 weeks and liver tissue samples were then collected. High-throughput sequencing was utilized to analyze mouse liver tissue samples to obtain differential lncRNA expression profiles. RSV or MET both reduced the blood glucose levels, the insulin index and the area under the curve in HFD-fed mice. Treatment also improved liver structure and decreased lipid deposition in liver tissues, as shown by H&E and Oil Red O staining. Compared with the MET group, there were 55 lncRNAs and 19 mRNAs with a differential expression. In total, eight lncRNAs were randomly selected and evaluated by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The results of seven lncRNAs corresponded to those of the sequencing analysis. Pathway analysis revealed that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway had the highest enrichment score. In addition, the results of western blot analysis and RT-qPCR revealed that the expression levels of forkhead box O1, glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1 and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 in the RSV and MET groups were significantly decreased compared with those in the HFD group. NONMMUT034936.2 and G6PC target genes exhibited similar expression patterns, indicating that RSV and MET may affect the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through NONMMUT034936.2 to attenuate insulin resistance. On the whole, the present study provides novel biomarkers or contemporary perspectives for the use of RSV and MET in the treatment of insulin resistance and diabetes.

Keywords: resveratrol, metformin, long non-coding RNA, high-throughput sequencing, insulin resistance

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a multifactorial disease, and its prevalence has been increasing yearly over the past century. The pathogenesis of this disease is considered to be very complex. One of the main factors of this pathogenesis is the blockade of the insulin signaling pathway, leading to insulin resistance (1), which is mainly manifested by the insensitivity of the target organ of insulin to insulin signals.

Resveratrol (RSV) is a polyphenolic compound found in a variety of plants. It is a natural phytoalexin that exists mainly in the trans structure. It has been detected in >70 plants, including eucalyptus and banyan, and dietary sources mainly include red grapes, mulberries and red wine, with the highest content found in the Chinese traditional medicine, Polydatin (2,3). Metformin (MET) is a first-line anti-diabetic drug that is widely used in the treatment of T2DM. It mainly reduces blood glucose levels by inhibiting the secretion of liver glucose and increasing the sensitivity to insulin (4). A previous study demonstrated that RSV plays a beneficial role in improving insulin resistance and treating T2DM and related complications through a variety of biological effects, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, cardiovascular and neuroprotective effects (5). MET exerts similar effects to RSV, and its beneficial effects on human health have been demonstrated to be even more prominent than those of RSV (6).

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have a length of ~200 nucleotides. lncRNAs were originally considered to be 'noise' in genome transcription without a biological function. However, recent studies have indicated that lncRNAs are involved in a number of important regulatory processes, such as genomic imprinting and chromatin modification (7), and play a role in the treatment of T2DM (8). In spite of this information, the functional mechanisms of the majority of lncRNAs remain unclear. The authors have previously studied lncRNA expression profiling following treatment with RSV to improve insulin resistance (9). To the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have reported an analysis of lncRNA expression profiles resulting from RSV and MET treatment for high-fat diet (HFD)-induced liver insulin resistance in mice. The present study thus aimed to explore the potential role of RSV and MET in improving liver insulin resistance through lncRNAs and to provide novel concepts and targets for the treatment of T2DM.

Materials and methods

Animals

The animal experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the People's Hospital of Hebei Province and complied with international regulations for the management of experimental animals. A total of 40 male C57BL/6J mice (6 weeks old, weighing 21.0-23.0 g) were purchased from Beijing Weitong Lihua Experimental Animal Center [license no. SCXK (Beijing) 2016-0006] and maintained at the Animal Laboratory of the Clinical Research Center of Hebei General Hospital under a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water.

Animal food

Animal food was purchased from Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. [ordinary feed D12450J (calorie composition: 20% protein, 70% carbohydrate and 10% fat; 3.85 kcal/g) and high-fat feed D12492 (calorie composition: 20% protein, carbohydrates 20 and 60% fat; 5.24 kcal/g)].

Establishment of animal models

The C57BL/6J mice were randomly divided into the control (CON, n=10) and HFD (n=30) groups. The CON group was provided with ordinary feed, and the HFD group was provided with the high-fat feed. After 8 weeks, an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed. According to the weight of the mice, 2 g/kg glucose in saline were injected intraperitoneally, and the blood glucose concentration was measured by blood sampling from the tail vein using a blood glucose meter (Johnson & Johnson) at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min, as previously described (10,11). The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to confirm a glucose metabolic disorder and to determine whether the insulin resistance model was successfully established.

RSV and MET treatments

The mice in the HFD group were randomly divided into three groups as follows: 10 mice in the HFD control group, 10 mice in the HFD + RSV group, and 10 mice in the HFD + MET group. RSV (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at a concentration of 100 mg/kg/day and MET (Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.) at a concentration of 250 mg/kg/day were administered to the mice. The CON and HFD groups were administered a 0.9% sodium solution containing 0.1% DMSO daily. The sodium solution was administered to the stomach, and the IPGTT was performed after 8 weeks. The doses of RSV and MET were similar to those used in previous studies using rodents (12,13). RSV was used at 100 mg/kg/day and MET at 250 mg/kg/day in preliminary experiments to attenuate insulin resistance. A previous study proved that RSV (100 mg/kg/day) used in mice did not cause damage to liver function (14). In addition, in a previous study, the authors demonstrated that 100 mg/kg/day RSV did not damage liver function (15). Animal and food weights were recorded weekly throughout the experiment.

Tissue collection

Following 8 weeks of RSV and MET treatments, and 72 h after the final IPGTT, 3 mice from each group were randomly selected and injected intraperitoneally with insulin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 1.5 IU/40 g at 20 min prior to anesthesia (mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 2% pentobarbital sodium at 45 mg/kg). All mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and blood was then collected by cardiac puncture. The liver was rapidly excised and weighed; a small section was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and the remaining tissues were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then transferred to a −80°C freezer for storage.

Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI)

According to the fasting blood glucose and insulin concentration, a QUICKI was obtained (16). QUICKI value=1/(lgI0 + lgG0), where I0 is fasting insulin and G0 is fasting blood glucose.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

The liver tissue samples fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were dehydrated with gradient alcohol solutions (100, 95, 80 and 75%), embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned serially at a thickness of 5 µm. The sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin for 5 min at 25°C (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). The sections were then differentiated with 70% ethanol for 10 sec, followed by washing with distilled water. Finally, the sections were stained with eosin for 5 min at 25°C (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), dehydrated and sealed with resin. The morphological characteristics of the liver sections were observed under a light microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Oil Red O staining

The collected tissues were frozen and sectioned at a thickness of 5-10 nm. The sections were placed in an Oil Red O solution for 5-15 min at 25°C (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) while being protected from light and then differentiated with 75% alcohol, followed by washing with distilled water. After staining the nuclei with hematoxylin for 2 min at 25°C), the sections were washed with distilled water until the nuclei became blue for 5-10 min and then sealed glycerin-gelatin. The morphological characteristics of the sections were observed under an optical microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from the liver tissues using RIPA buffer (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and the protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). SDS-PAGE separation gels (8, 10 and 12%) were prepared at various concentrations according to the molecular weight of the target protein. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane that was blocked with 5% dry skim milk for 3 h at 25°C. Primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution were as follows: β-actin (mouse antibody, 1:1,000; cat. no. 3700S); t-PI3K (rabbit antibody, 1:2,000; cat. no. 4249S); p-PI3K (Tyr 458; rabbit antibody, 1:1,000; cat. no. 17366S); t-Akt rabbit antibody, 1:2,000; cat. no. 4691S); p-Akt (Ser 473) rabbit antibody, 1:1,000 cat. no. 4060S) (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.); forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) (rabbit antibody, 1:1,000; cat. no. 18592-1-AP); glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1 (G6PC) (rabbit antibody, 1:2,000 cat. no. 22169-1-AP) (all from ProteinTech Group, Inc.); phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (PCK1; PEPCK) (rabbit antibody, 1:1,000 cat. no. 702748; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.); HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody and goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:8,000; cat. no. L3012-2; and 1:3,000, cat. no. L3032-2 respectively; both from Signalway Antibody LLC). The primary antibodies were incubated with the membrane at 4°C overnight, followed by washing three times (10 min each time) with TBST (20% Tween), followed by incubation with the secondary antibodies at room temperature for 50 min, and washing three times (10 min each time) with TBST (20% Tween). A gel imaging instrument was used to capture specific protein bands. ImageJ software 1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health) was used to measure the densitometric values of the protein bands. Normalization was performed by incubating the same membrane with an antibody against β-actin for 2 h at 25°C).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the mouse liver tissues using TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA (RR047A) using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit with a gDNA Eraser kit and amplified using a SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (RR820A; Takara Bio, Inc.). PCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7300 apparatus (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles for 15 sec at 95°C, 15 sec at 95°C and 15 sec at 60°C. The 2−ΔΔCq method (17) was used to normalize the gene expression levels to β-actin. The primer sequences are listed in Table I. Primers for the lncRNAs were designed by Shanghai Simomics based on lncRNA sequences from the NONCODE database (http://www.noncode.org/).

Table I.

Sequences of primers used for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR used in the present study.

| Gene | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Actin | GGCGCTTTTGACTCAGGATT | GGGATGTTTGCTCCAACCAA |

| NONMMUT022720.2 | CTCACCTCCATTTCCTTCCATAT | AGACCTCACCTGATCTCCACCC |

| NONMMUT020098.2 | TTATGTAGTGCCTTCCATTGTCC | CTCTTCCATAGCCAGAACTGCA |

| NONMMUT051900.2 | GTGGCTGGACAGTTCCTACCTT | ATAACTCGCCCACCGCACT |

| NONMMUT051843.2 | AGGCTAAGAGCAGCAGCAAGT | AAGCACCAACTGCATACTCCC |

| NONMMUT042412.2 | CTGACCGACTGGCAAGTGAATA | TGTGCGGACATAGATGCTGAA |

| NONMMUT006741.2 | TCAGTTAAGCAGCACAATGGC | AGTATTCTTACCCACTGAGCCATC |

| NONMMUT148967.1 | CTCCAACCCACCAACAGCATA | AAACAACGGTGGCATGGAATA |

| NONMMUT034936.2 | CCAGCCACTCTGCACTTTGTT | AGTCCTATCTGTCCACCCTCCG |

| PI3K | ACTTTGTGACCTTCGGCTT | TCCTGTACTTCTGGATCTTTAA |

| Akt | AAGGAGGTCATCGTCGCCAA | ACAGCCCGAAGTCCGTTATC |

| FOXO1 | AAGGCCATCGAGAGCTCAGC | GATTTTCCGCTCTTGCCTCC |

| G6PC | TTGCATTCCTGTATGGTAGTGG | TAGGCTGAGGAGGAGAAAACTG |

| PEPCK | GTGCTGGAGTGGATGTTCGG | CTGGCTGATTCTCTGTTTCAGG |

FOXO1, forkhead box O1; G6PC, glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1.

High-throughput sequencing

A total of four liver samples each were selected from the CON, HFD, HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups, and total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen GmbH) and TruSeq™ RNA sample preparation reagents (Illumina, Inc.). A cassette (Illumina, Inc.) was used to construct a sequencing library. The purified library was verified using the Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for the insert size and calculated molarity. Finally, sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, Inc.). The library was constructed and sequenced by Shanghai Simomics. The high-throughput sequencing results were uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession no. GSE137840).

Identification and expression analyses of lncRNAs and mRNAs

Fragments were counted within each gene segment to calculate the fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) value for each gene (18). The differential expression of genes between groups was then analyzed. After calculating the P-value, multiple hypothesis test correction was performed by controlling the false discovery rate (FDR). The corrected P-value is termed the Q-value. Fold changes in differential expression were calculated based on the FPKM value, and the log2 (fold change) was then calculated to subsequently screen differentially expressed genes, as previously described (19). Both lncRNAs and mRNAs were obtained from databases [lncRNAs: RefSeq (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/), Ensembl (https://asia.ensembl.org/index.html) and GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/); mRNAs: NONCODE (http://www.noncode.org/) and Ensembl].

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis

To investigate the main biological functions and pathways related to the differentially expressed genes, each gene was annotated based on the GO and KEGG databases. Fisher's exact test or Chi-squared test were used to calculate the number of differentially expressed genes, and the hypergeometric test was then used for statistical analysis to select the GO and KEGG entries that were significantly enriched for the differentially expressed genes. After the calculated P-value was corrected by multiple hypothesis testing, a Q-value ≤0.05 was used as the threshold. Meeting this condition was defined as the GO and KEGG results that were significantly enriched for differentially expressed genes.

lncRNA target gene prediction

The mRNA that interacts with lncRNA is termed the target gene of lncRNA. cis target gene prediction involved the identification of mRNAs in the 10 kb range of lncRNA upstream and downstream on the genome as the target gene of the lncRNA. The prediction of trans target genes was based on the principle of sequence complementary pairing, using blast alignment to obtain mRNA complementary to lncRNA. RNAplex 0.2 software (University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany) was used to calculate the thermodynamic parameter values of lncRNAs and mRNAs following complementary pairing. The result above the software threshold ranges was selected as the target gene of the lncRNA.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS, Inc.). The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. An independent samples t-test (Student's t-test) was used for two-sample comparisons with data demonstrating a normal distribution. Multiple groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's or Tamhane's test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant differences. For lncRNA and mRNA expression, significant level changes were expressed as a Q-value <0.05, and the absolute value of fold change was greater than or equal to twice the change.

Results

Establishment of the mouse model of HFD-induced insulin resistance

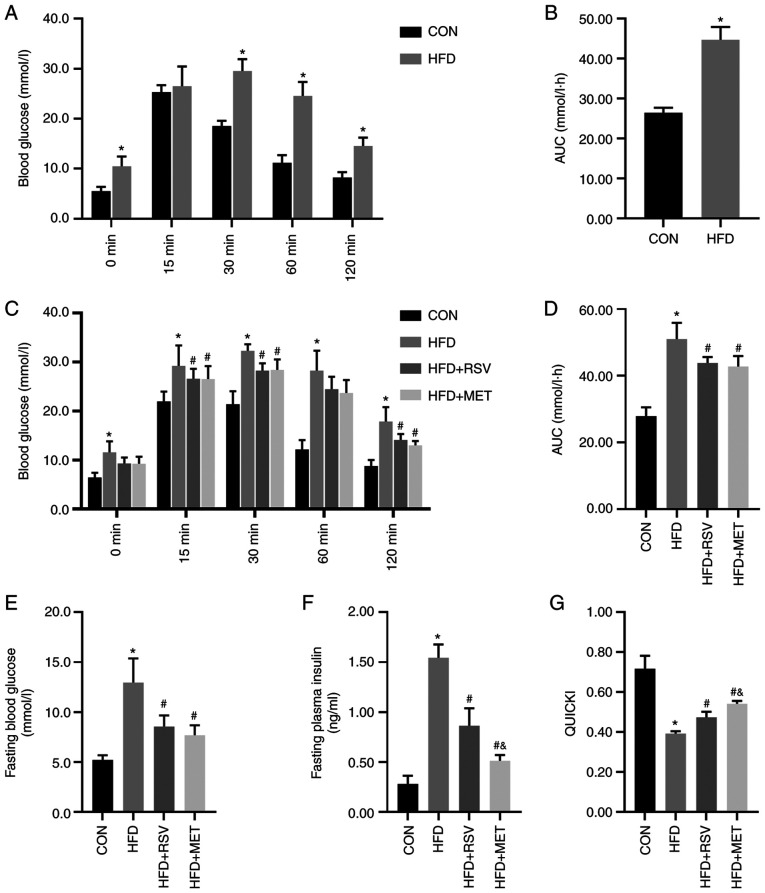

At the end of week 8, IPGTTs were performed on the two groups of mice. The mice in the HFD group had significantly higher blood glucose levels than those in the CON group at 0, 30, 60 and 120 min (Fig. 1A). Compared with the CON group, the AUC in the HFD group was significantly increased (Fig. 1B), indicating that the model of insulin resistance was successfully established.

Figure 1.

RSV and MET intervention and the IPGTT results before and after 8 weeks of being fed the HFD, and insulin sensitivity after RSV and MET treatment. After 8 weeks of high-fat diet. (A) Blood glucose levels at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after the IPGTT. (B) AUC of glucose. (C) Blood glucose levels at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after the IPGTT, (D) AUC of glucose, (E) fasting blood glucose levels, (F) fasting blood insulin levels, and (G) QUICKI after 8 weeks of treatment. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=10). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis followed by Tukey's or Tamhane's multiple comparison tests. *P<0.05 vs. CON; #P<0.05 vs. HFD; and &P<0.05 vs. HFD + RSV. RSV, resveratrol; MET, metformin; HFD, high-fat diet; IPGTT, intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test; AUC, area under the curve; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index.

Changes in general indices of mice in each group following treatment with RSV and MET for 8 weeks

As shown by the results of the IPGTT, compared with the CON group, the HFD group had significantly higher blood glucose levels at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min (Fig. 1C). Compared with the HFD group, the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups had significantly decreased blood glucose levels at 30, 60 and 120 min. No statistically significant difference in glucose levels was observed between the HFD + MET and HFD + RSV groups (Fig. 1C). Compared with the CON group, the AUC in the HFD group was significantly increased. Compared with the HFD group, the AUC in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups was significantly decreased. Similarly, compared with the HFD + RSV group, the AUC in the HFD + MET group did not differ significantly (Fig. 1D).

Blood glucose, insulin and QUICKI

Compared with the CON group, the fasting blood glucose and insulin levels in the HFD group were significantly increased and the QUICKI value was significantly decreased. Compared with the HFD group, the fasting blood glucose and insulin levels in HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups were significantly decreased, and the QUICKI value was significantly increased. Compared with the HFD + RSV group, significant differences were observed in fasting blood glucose levels in the HFD + MET group, the insulin level was significantly decreased and the QUICKI value was significantly increased (Fig. 1E-G).

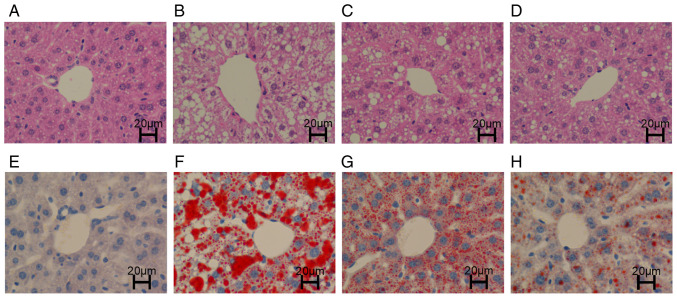

H&E staining

The liver structure of the mice in the CON group was clear and intact, the cytoplasm was uniformly stained red, and essentially, no lipid droplets were vacuolated (Fig. 2A). However, the structure in the HFD group was disordered and fuzzy, and a large number of large lipid droplet vacuoles were observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B). The liver structures in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups were clear, and the cytoplasm was stained red. A small number of smaller lipid droplet vacuoles were observed in the cytoplasm. Compared with the HFD + RSV group, the number of lipid droplet vacuoles was markedly decreased in the HFD + MET group (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Hepatic lipid deposition following treatment with RSV and MET. (A-D) H&E staining of liver tissue. (E-H) Oil Red O staining of liver tissue. (A and E) The CON group exhibited a normal liver morphology. (B and F) The HFD group exhibited a large number of lipid droplet vacuoles. (C and G) The HFD + RSV group had less vacuoles compared with the HFD group. (D and H) Compared with the HFD + RSV group, the HFD + MET group did not exhibit vacuoles. RSV, resveratrol; MET, metformin; HFD, high-fat diet; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. Scale bar (H) 20 µm.

Oil Red O staining

The liver structure in the CON group was clear with blue nuclei (Fig. 2E). In the HFD group, a large number of orange-red lipid droplets were deposited, and a large number of lipid droplet vacuoles were observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2F). Compared with the HFD group, the orange-red lipid droplet deposition and lipid droplet vacuoles were markedly decreased in the HFD + RSV group. Compared with the HFD + RSV group, the orange-red lipid droplet deposition and lipid droplet vacuoles were markedly decreased in the HFD + MET group. Orange-red lipid droplets were less evident, and intracellular cytoplasmic lipid droplet vacuoles were essentially absent (Fig. 2G and H).

Expression profiles of lncRNAs and mRNAs

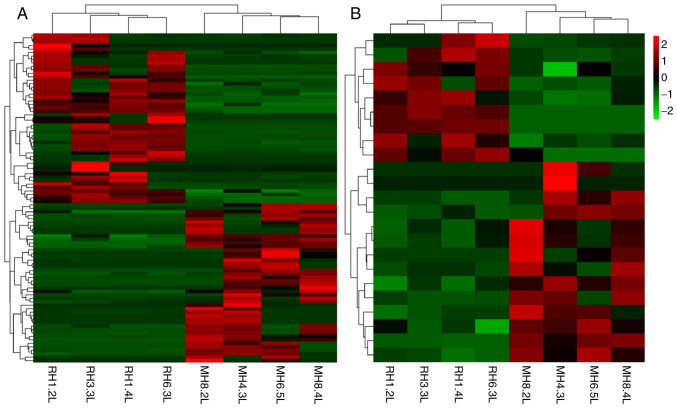

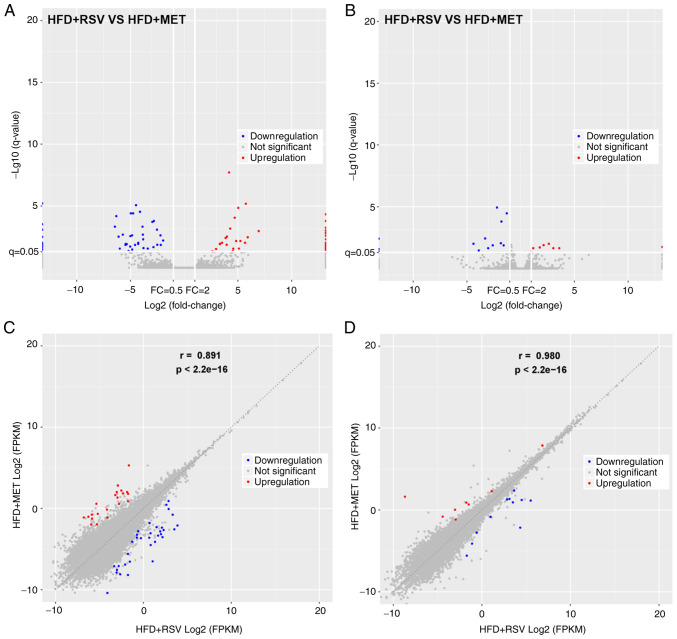

The expression of lncRNAs and mRNAs in the livers of mice in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups was determined using high-throughput sequencing and comparisons were made between the groups. A total of 55 differentially expressed lncRNAs (21 upregulated and 34 downregulated) (Table II) and 19 mRNAs with a differential expression (8 upregulated and 11 downregulated) (Table III) were detected. A heatmap (Fig. 3A and B), volcano plot (Fig. 4A and B) and scatter plot (Fig. 4C and D) were used to reveal the trend distribution and approximate numbers of lncRNAs and mRNAs with a differential expression.

Table II.

Expression patterns of lncRNAs in mice fed a high-fat diet and treated with resveratrol (HFD + RSV), or a high-fat diet and treated with metformin (HFD + MET).

| Sequence name | Log2 (fold change) | Q-value | Regulation (HFD + RSV vs. HFD + MET) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NONMMUT005824.2 | 6.945314896 | 0.001103259 | Up |

| NONMMUT115986.1 | 5.919352903 | 0.003509737 | Up |

| NONMMUT006741.2 | 5.740878779 | 6.66935E-06 | Up |

| NONMMUT057779.2 | 5.667763678 | 0.009685873 | Up |

| NONMMUT142367.1 | 5.237843416 | 0.006999248 | Up |

| NONMMUT029743.2 | 5.101371421 | 0.028598401 | Up |

| NONMMUT042412.2 | 5.046285872 | 1.44559E-05 | Up |

| NONMMUT063026.2 | 4.847521228 | 0.006999248 | Up |

| NONMMUT054509.2 | 4.713077677 | 9.15681E-05 | Up |

| NONMMUT141988.1 | 4.577511628 | 0.029246228 | Up |

| NONMMUT072307.2 | 4.527671546 | 0.04528547 | Up |

| NONMMUT148967.1 | 4.292139587 | 0.000683204 | Up |

| NONMMUT059852.2 | 4.183739876 | 1.96211E-08 | Up |

| NONMMUT025403.2 | 3.987442869 | 0.003079426 | Up |

| NONMMUT060871.2 | 3.958045958 | 0.014100955 | Up |

| NONMMUT049810.2 | 3.863840709 | 0.00397755 | Up |

| NONMMUT019208.2 | 3.533115587 | 0.009730051 | Up |

| NONMMUT114839.1 | 3.337496324 | 0.012511971 | Up |

| NONMMUT034936.2 | 3.333006304 | 0.011416228 | UP |

| NONMMUT018410.2 | 2.975401761 | 0.030868204 | Up |

| ENSMUST00000168978 | 2.631296088 | 0.047219725 | Up |

| ENSMUST00000206358 | −7.561291886 | 1.21828E-26 | Down |

| NONMMUT001350.2 | −6.43793958 | 0.000481319 | Down |

| NONMMUT139135.1 | −6.306143865 | 6.77556E-05 | Down |

| NONMMUT051900.2 | −6.09393297 | 0.003117525 | Down |

| NONMMUT023599.2 | −5.982081496 | 0.028601178 | Down |

| NONMMUT012522.2 | −5.701207169 | 0.002142543 | Down |

| NONMMUT153354.1 | −5.453670717 | 0.014465309 | Down |

| NONMMUT036927.2 | −5.428733989 | 0.012009699 | Down |

| NONMMUT041613.2 | −5.334514214 | 0.012511971 | Down |

| NONMMUT012373.2 | −5.164885661 | 0.045254749 | Down |

| NONMMUT060208.2 | −5.008870996 | 0.019601564 | Down |

| ENSMUST00000181220 | −4.99779716 | 0.002812713 | Down |

| NONMMUT020098.2 | −4.951796068 | 4.02751E-05 | Down |

| NONMMUT146959.1 | −4.834859279 | 0.002445414 | Down |

| NONMMUT144581.1 | −4.826441656 | 0.034149857 | Down |

| NONMMUT051843.2 | −4.741021643 | 4.02751E-05 | Down |

| NONMMUT152719.1 | −4.561542794 | 0.014465309 | Down |

| NONMMUT017165.2 | −4.468435793 | 8.73827E-06 | Down |

| NONMMUT144108.1 | −4.273674469 | 0.012078574 | Down |

| NONMMUT002990.2 | −4.266195398 | 0.009730051 | Down |

| NONMMUT068763.2 | −4.10312612 | 3.01531E-05 | Down |

| NONMMUT004068.2 | −3.866535764 | 0.000481319 | Down |

| NONMMUT153572.1 | −3.834650085 | 0.002142543 | Down |

| NONMMUT012873.2 | −3.807527476 | 0.005135465 | Down |

| ENSMUST00000210097 | −3.77697909 | 0.02615524 | Down |

| NONMMUT003373.2 | −3.374798374 | 0.028601178 | Down |

| NONMMUT008156.2 | −2.945595627 | 0.000198272 | Down |

| NONMMUT016564.2 | −2.848305902 | 0.021844713 | Down |

| NONMMUT087168.1 | −2.809338304 | 0.000167272 | Down |

| NONMMUT078378.1 | −2.520230112 | 0.000848005 | Down |

| NONMMUT022720.2 | −2.494349474 | 0.014100955 | Down |

| ENSMUST00000194058 | −2.195755365 | 0.002445414 | Down |

| MSTRG.5260.1 | −2.16480654 | 0.014465309 | Down |

| NONMMUT145427.1 | −1.950332233 | 0.006382243 | Down |

Table III.

Expression patterns of mRNAs in mice fed a high-fat diet and treated with resveratrol (HFD + RSV), or a high-fat diet and treated with metformin (HFD + MET).

| Gene name | Log2 (fold change) | Q-value | Regulation (HFD + RSV vs. HFD + MET) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usp50 | 10.30770702 | 2.7191E-101 | Up |

| Capn11 | 3.604562962 | 0.022920926 | Up |

| Gm45301 | 3.05478554 | 0.022920926 | Up |

| Gm20427 | 2.635920148 | 0.010059961 | Up |

| Gm15622 | 2.14891265 | 0.012986671 | Up |

| Zfp872 | 1.789734813 | 0.019946447 | Up |

| Wdr81 | 1.184060009 | 0.022920926 | Up |

| G6pc | 1.003683239 | 0.037709999 | Up |

| Gm10774 | −6.495776415 | 7.6787E-21 | Down |

| Mt2 | −4.377392087 | 0.010059961 | Down |

| Epo | −3.8837058 | 0.034838444 | Down |

| Mt1 | −3.289829351 | 0.003737438 | Down |

| 9330175E14Rik | −3.009727309 | 0.022920926 | Down |

| Gm20634 | −2.583854697 | 0.013400526 | Down |

| Gm38253 | −2.191694611 | 1.16607E-05 | Down |

| Gm8242 | −1.830508486 | 0.009095243 | Down |

| Pcsk9 | −1.774792296 | 0.000159695 | Down |

| Tff3 | −1.570997721 | 0.013618716 | Down |

| Tspan4 | −1.278414166 | 3.46456E-05 | Down |

Figure 3.

Clustering heatmap of lncRNAs and mRNAs between the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET group. (A) lncRNAs; (B) mRNAs. Red area represents lncRNAs (or mRNAs) with P<0.05 and fold change ≥2; green area represents lncRNAs (or mRNAs) with P<0.05 and fold change ≤2. RSV, resveratrol; MET, metformin; HFD, high-fat diet; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

Figure 4.

(A and B) Volcano and (C and D) scatter plots of the variations in lncRNAs and mRNAs between the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups. (A and C) lncRNAs; (B and D) mRNAs. Red dots represent lncRNAs (or mRNAs) with P<0.05 and fold change ≥2; blue dots represent lncRNAs (or mRNAs) with P<0.05 and fold change ≤2. RSV, resveratrol; MET, metformin; HFD, high-fat diet; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

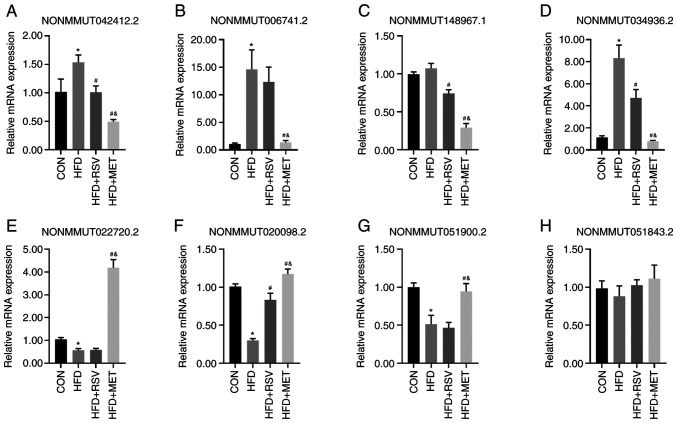

Validation of lncRNA expression using RT-qPCR

From the 55 lncRNAs with a differential expression in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups, four randomly selected lncRNAs upregulated in the HFD + RSV group (NONMMUT042412.2, NON MMU T0 06741.2, NON MMU T148967.1 and NONMMUT034936.2) (Fig. 5A-D) and four lncRNAs downregulated in the HFD + RSV group (NONMMUT022720.2, NONMMUT020098.2, NONMMUT051900.2 and NONMMUT051843.2) (Fig. 5E-H) were used to verify the sequencing results using RT-qPCR. Apart from NONMMUT051843.2, the expression levels of the other seven lncRNAs were consistent with the sequencing results in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups. Compared with the CON group, apart from the expression levels of NONMMUT148967.1 and NONMMUT051843.2 in the HFD group, those of the other lncRNAs differed significantly. Compared with the HFD group, apart from the expression levels of NONMMUT006741.2, NONMMUT022720.2, NONMMUT051900.2 and NONMMUT051843.2, those of the other lncRNAs in the HFD + RSV group differed significantly.

Figure 5.

Validation of four upregulated and four downregulated lncRNAs using RT-qPCR in the HFD + RSV group compared with the HFD + MET group. (A-D) Four upregulated lncRNAs; (A) NONMMUT042412.2; (B) NONMMUT006741.2; (C) NONMMUT148967.1; and (D) NONMMUT034936.2. Four downregulated lncRNAs; (E) NONMMUT022720.2; (F) NONMMUT020098.2; (G) NONMMUT051900.2.; and (H) NONMMUT051843.2. All results were obtained from three independent experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=4). One-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis followed by Tukey's or Tamhane's multiple comparison tests. *P<0.05 vs. CON; #P<0.05 vs. HFD; &P<0.05 vs. HFD + RSV. RSV, resveratrol; MET, metformin; HFD, high-fat diet; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

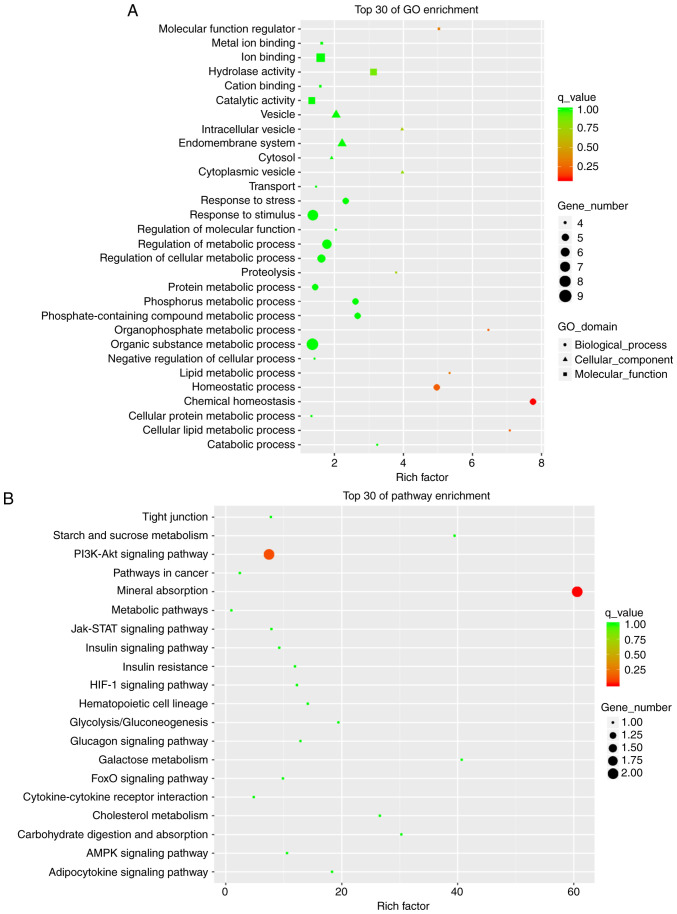

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

GO analysis includes 'Biological Process (BP)', 'Molecular Function (MF)' and 'Cellular Component (CC)'. The meaningful BPs in the top 30 mRNA enrichments of the GO analysis mainly included 'chemical homeostasis', 'homeostatic process' and 'cellular lipid metabolic process'. CC mainly included 'cytoplasmic vesicle' and 'intracellular vesicle'. MF included 'molecular function regulator' and 'hydrolase activity' (Fig. 6A). KEGG pathway analysis revealed the signaling pathways in which mRNAs with major differences were involved. The top 30 pathway enrichments included 'mineral absorption' and the 'PI3K-Akt signaling pathway'. Among these, the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is related to the liver insulin resistance model of the HFD-fed mice (Fig. 6B). This pathway We selected and the closely related target gene predicted was G6PC through pathway analysis. Among the eight verified lncRNAs, NONMMUT034936.2 exhibited a similar trend in expression as this target gene, as discussed below.

Figure 6.

Top 30 of terms GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs. (A) GO analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs; (B) KEGG pathway analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

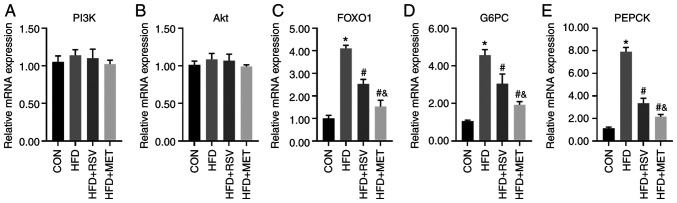

Comparison of the mRNA levels of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-related genes

The mRNA levels of several key molecules in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, namely PI3K, Akt, FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK, were compared in the livers of mice in the CON, HFD, HFD + RSV, and HFD + MET groups using RT-qPCR. No significant differences in the mRNA expression levels of PI3K and Akt were observed among these four groups (Fig. 7A and B). Compared with the CON group, the mRNA levels of FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK were significantly increased in the HFD group, and those in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups were significantly decreased compared with those in the HFD group. Compared with the HFD + RSV group, the mRNA levels of FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK in the HFD + MET group were significantly decreased (Fig. 7C-E).

Figure 7.

Relative mRNA expression of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-related indicators in mouse liver. (A) PI3K; (B) Akt; (C) FOXO1; (D) G6PC; (E) PEPCK. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=4). One-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis followed by Tukey's or Tamhane's multiple comparison tests. *P<0.05 vs. CON; #P<0.05 vs. HFD; &P<0.05 vs. HFD + RSV. RSV, resveratrol; MET, metformin; HFD, high-fat diet; FOXO1, forkhead box O1; G6PC, glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1.

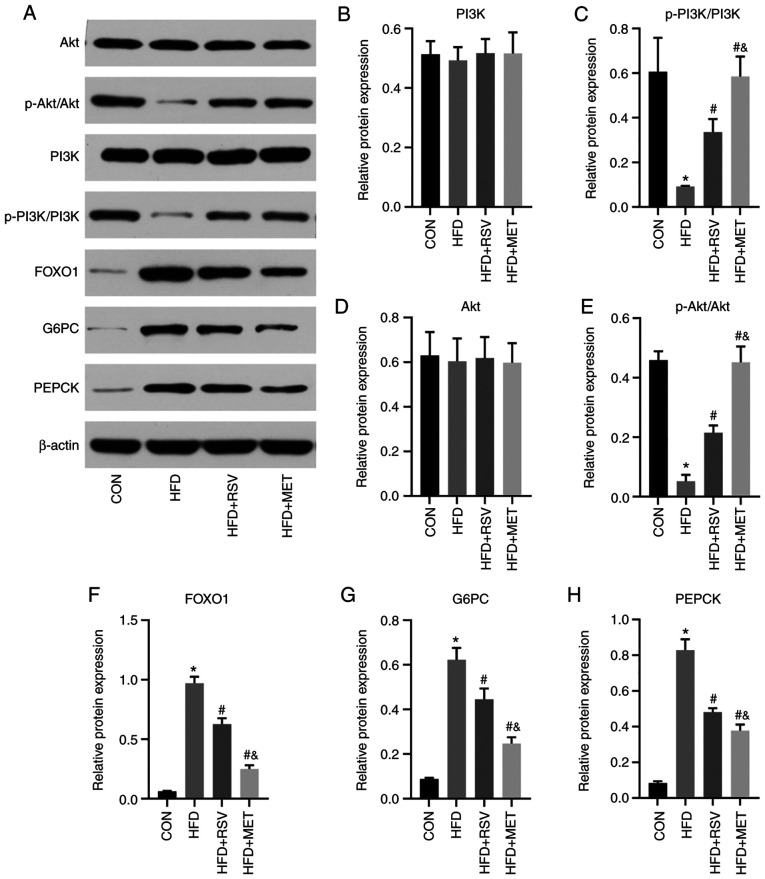

Comparison of protein levels of PI3K/Akt signaling pathwayrelated genes

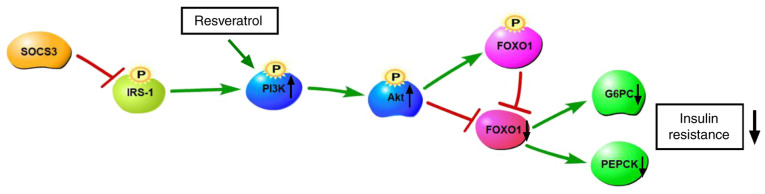

The same key molecules were selected to verify and compare their protein levels using western blot analyhsis in the four groups of mouse liver tissues (Fig. 8A). Compared with the CON group, the levels of p-PI3K and p-Akt in the HFD group were significantly decreased (Fig. 8C and E), while those of FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK were significantly increased (Fig. 8F-H). Compared with the HFD group, the levels of p-PI3K and p-Akt in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups were significantly increased (Fig. 8C and E), while those of FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK were significantly decreased (Fig. 8F-H). Compared with the HFD + RSV group, the HFD + MET group exhibited significantly increased expression levels of p-PI3K and p-Akt (Fig. 8C and E), and significantly decreased expression levels of FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK (Fig. 8F and H). No significant differences were observed in the total PI3K and Akt expression levels among the four groups (Fig. 8B and D). The aforementioned results indicate that RSV may attenuate insulin resistance via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Fig. 9).

Figure 8.

Relative protein expression of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-related indicators in mouse liver. (A) Protein bands of PI3K-Akt signal pathway molecules; (B) PI3K; (C) p-PI3K/PI3k; (D) Akt; (E) p -Akt/Akt; (F) FOXO1; (G) G6PC; (H) PEPCK. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). One-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis followed by Tukey's or Tamhane's multiple comparison tests. *P<0.05 vs. CON; #P<0.05 vs. HFD; &P<0.05 vs. HFD + RSV. RSV, resveratrol; MET, metformin; HFD, high-fat diet; FOXO1, forkhead box O1; G6PC, glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1.

Figure 9.

Resveratrol attenuates insulin resistance via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate 1; FOXO1, forkhead box O1; G6PC, glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1.

Discussion

The liver is the main organ for glucose metabolism (20,21). The abnormal activity of gluconeogenesis can lead to an increased endogenous glucose production, a major pathophysiological factor that causes T2DM and insulin resistance (22). The gluconeogenesis pathway mainly depends on two rate-limiting enzymes, G6PC and PEPCK (23). A variety of hormones and signaling pathways affect gluconeogenesis by influencing the transcription and expression of these enzymes. PI3K/Akt is the main signal transduction pathway for insulin to exert physiological effects in the liver. FOXO1 is a downstream molecule of PI3K/Akt signaling and an essential molecule in the liver to regulate blood insulin levels. It mainly promotes gluconeogenesis in the fasting liver by regulating the expression of G6PC and PEPCK (24). The overexpression of FOXO1 upregulates G6PC and PEPCK expression, which promotes increased liver gluconeogenesis, impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance when fasting, and inhibits liver gluconeogenesis when FOXO1 expression is lost, at which time glucose utilization is enhanced and insulin sensitivity increases (25).

RSV is a natural polyphenolic plant toxin that has received widespread attention in recent decades for the treatment of metabolic diseases, such as T2DM, particularly to improve insulin resistance (26). Studies have demonstrated that RSV increases glucose uptake through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the absence of insulin (Fig. 9). The mechanisms through which RSV improves insulin resistance involve a significant increase in Akt phosphorylation levels (27). MET is a representative T2DM drug. Its main target organ is the liver. MET effectively reduces blood glucose levels by down regulating G6PC and PEPCK to inhibit liver glucose secretion (28).

In the present study, both RSV and MET reduced blood glucose levels, the insulin index and the AUC in HFD-fed mice, and increased the QUICKI. In terms of the area AUC curve and QUICKI, MET exerted more prominent effects than RSV, and there was no significant differences in the other indicators. The results of H&E and Oil Red O staining of the liver tissues revealed that the morphological structure of the liver cells following treatment with RSV and MET was clearer and more complete than in the HFD group, the numbers of lipid droplets and vacuoles were decreased, and the volume became smaller. These results indicated that both RSV and MET attenuated insulin resistance and lipid deposition in the livers of HFD-fed mice.

A recent study demonstrated that lncRNAs play an important role in the development of T2DM. In such patients, a variety of lncRNAs are associated with insulin resistance in peripheral blood (29). Among these, the expression of lncRNA H19 has been shown to be significantly decreased in the skeletal muscle of patients with T2DM and in insulin-resistant animals (30); H19 was the first lncRNA reported to be related to gestational diabetes and inhibit insulin secretion (31). Another study demonstrated that the downregulation of lncRNA MALAT1 improved glucose metabolism disorders in rats with T2DM, and MALAT1 may be a potential serum marker for gestational diabetes (32). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports available to date on insulin-resistant, HFD-fed animal models treated with RSV and MET comparing the changes in lncRNA expression.

In the present study, using high-throughput sequencing, 55 lncRNAs and 19 mRNAs with a differential expression were found in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups. A total of eight lncRNAs were selected for verification using RT-qPCR. Apart from NONMMUT051843.2, the expression levels of the other seven lncRNAs were consistent with the sequencing results in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups, indicating that the sequencing results were reliable. By performing GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of these 19 differentially expressed mRNAs, it was found that the numbers of research areas and signaling pathways that were enriched were very small, and only the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway was related to the insulin resistance in the present study. The functional difference between RSV and MET was not evident. Pathway analysis was used to predict the target gene in G6PC, which is closely related to this pathway. The expression of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-related molecules was measured using RT-qPCR. The expression levels of FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK were compared between the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups. Compared with the HFD group, the levels of FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK were significantly decreased. The levels in the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups were significantly decreased. It is noteworthy that the NONMMUT034936.2 and G6PC target genes exhibited similar expression patterns, indicating that RSV and MET may affect the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through NONMMUT034936.2 to increase insulin sensitivity. Similarly, the present study verified PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-related molecules of PI3K, Akt, FOXO1, G6PC and PEPCK using western blot analysis and similar results were obtained as those from RT-qPCR. These results demonstrated that, although there were differences in the levels of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-related molecules between the HFD + RSV and HFD + MET groups, the trend in these differences was that the mice fed the HFD exhibited decreased levels of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-related molecules, and MET treatment eased insulin resistance. Therefore, this difference indicated that MET may be more effective than RSV in attenuating insulin resistance. This may be linked to the animal model, drug dose, timing of the treatments, and differences in the selected tissue.

Through high-throughput sequencing, the present study found 55 lncRNAs with a differential expression in the HFD + RSV group compared with the HFD + MET group. Verification analysis revealed that the lncRNAs may be involved in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. RSV or MET may improve liver insulin resistance by regulating lncRNAs, and the effect of MET is more prominent. In addition, there is insufficient research on combination therapy with MET and RSV. Thus, the addition of a MET and RSV combined treatment group may be a valuable research direction to observe the effects of combined treatment. This may provide new insight for further research. The present study provides new concepts and treatment targets for RSV and MET intervention of T2DM. However, the present study only used animal models. The molecular biological functions and regulatory mechanisms of lncRNAs that improve insulin resistance still need to be studied further and verified in cell models.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that both RSV and MET attenuate liver insulin resistance by regulating lncRNAs, and MET exerts a more prominent effect. The RSV- and MET-regulated lncRNAs may prove to be potential therapeutic targets for T2DM.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The present study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (grant no. H2018307071).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

LS performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. XH performed the experiments and prepared the figures. CW established the mouse model. GS and HM designed the study and edited drafts of the manuscript. LS and XH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors contributed to data analysis, and the drafting or revising of the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was supervised and approved by the Ethics Committee of the People's Hospital of Hebei Province (no. 201920) and performed in accordance with the Regulations on the Administration of Laboratory Animals.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kim J, Bilder D, Neufeld TP. Mechanical stress regulates insulin sensitivity through integrin-dependent control of insulin receptor localization. Genes Dev. 2018;32:156–164. doi: 10.1101/gad.305870.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biasutto L, Mattarei A, Azzolini M, La Spina M, Sassi N, Romio M, Paradisi C, Zoratti M. Resveratrol derivatives as a pharmacological tool. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1403:27–37. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiskirchen S, Weiskirchen R. Resveratrol: How much wine do you have to drink to stay healthy? Adv Nutr. 2016;7:706–718. doi: 10.3945/an.115.011627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kai Y, Kawano Y, Yamamoto H, Narahara H. A possible role for AMP-activated protein kinase activated by metformin and AICAR in human granulosa cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:27. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0023-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbasi Oshaghi E, Goodarzi MT, Higgins V, Adeli K. Role of resveratrol in the management of insulin resistance and related conditions: Mechanism of action. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017;54:267–293. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2017.1343274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao W, Li A, Feng X, Hou T, Liu K, Liu B, Zhang N. Metformin and resveratrol ameliorate muscle insulin resistance through preventing lipolysis and inflammation in hypoxic adipose tissue. Cell Signal. 2016;28:1401–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu XF, Hao JL, Xie T, Pant OP, Lu CB, Lu CW, Zhou DD. The BRAF activated non-coding RNA: A pivotal long non-coding RNA in human malignancies. Cell Prolif. 2018;51:e12449. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Chang X, Zhang P, Fan L, Zhou T, Sun K. Aberrant expression of long non-coding RNAs in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes indicates potential roles in chronic inflammation and insulin resistance. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:2367–2378. doi: 10.1159/000484388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shu L, Hou G, Zhao H, Huang W, Song G, Ma H. Long non-coding RNA expression profiling following treatment with resveratrol to improve insulin resistance. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22:1303–1316. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao H, Zhang Y, Shu L, Song G, Ma H. Resveratrol reduces liver endoplasmic reticulum stress and improves insulin sensitivity in vivo and in vitro. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:1473–1485. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S203833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang YJ, Zhao H, Dong L, Zhen YF, Xing HY, Ma HJ, Song GY. Resveratrol ameliorates high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and fatty acid oxidation via ATM-AMPK axis in skeletal muscle. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:9117–9125. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201910_19315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaudoin MS, Snook LA, Arkell AM, Simpson JA, Holloway GP, Wright DC. Resveratrol supplementation improves white adipose tissue function in a depot-specific manner in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R542–R551. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00200.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristensen JM, Larsen S, Helge JW, Dela F, Wojtaszewski JF. Two weeks of metformin treatment enhances mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle of AMPK kinase dead but not wild type mice. PLoS One. 2013;13:e53533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng K, Song Z, Zhang H, Li S, Wang C, Zhang L, Wang T. The therapeutic effects of resveratrol on hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-induced obese mice by improving oxidative stress, inflammation and lipid-related gene transcriptional expression. Med Mol Morphol. 2019;52:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s00795-019-00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen K, Zhao H, Shu L, Xing H, Wang C, Lu C, Song G. Effect of resveratrol on intestinal tight junction proteins and the gut microbiome in high-fat diet-fed insulin resistant mice. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2020;71:965–978. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2020.1754351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hrebícek J, Janout V, Malincíková J, Horáková D, Cízek L. Detection of insulin resistance by simple quantitative insulin sensitivity check index QUICKI for epidemiological assessment and prevention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:144–147. doi: 10.1210/jc.87.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou Q, Mao Y, Hu L, Wu Y, Ji Z. miRClassify: An advanced web server for miRNA family classification and annotation. Comput Biol Med. 2014;45:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staehr P, Hother-Nielsen O, Beck-Nielsen H. The role of the liver in type 2 diabetes. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2004;5:105–110. doi: 10.1023/B:REMD.0000021431.90494.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen MC, Vatner DF, Shulman GI. Regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:572–587. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klover PJ, Mooney RA. Hepatocytes: Critical for glucose homeostasis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatting M, Tavares CDJ, Sharabi K, Rines AK, Puigserver P. Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2018;1411:21–35. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCurdy CE, Schenk S, Holliday MJ, Philp A, Houck JA, Patsouris D, MacLean PS, Majka SM, Klemm DJ, Friedman JE. Attenuated Pik3r1 expression prevents insulin resistance and adipose tissue macrophage accumulation in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes. 2012;61:2495–2505. doi: 10.2337/db11-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langlet F, Haeusler RA, Lindén D, Ericson E, Norris T, Johansson A, Cook JR, Aizawa K, Wang L, Buettner C, Accili D. Selective inhibition of FOXO1 activator/repressor balance modulates hepatic glucose handling. Cell. 2017;171:824–835.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiel G, Rössler OG. Resveratrol regulates gene transcription via activation of stimulus-responsive transcription factors. Pharmacol Res. 2017;117:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li JY, Huang WQ, Tu RH, Zhong GQ, Luo BB, He Y. Resveratrol rescues hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction via activation of Akt. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:182–191. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sathishkumar C, Prabu P, Mohan V, Balasubramanyam M. Linking a role of lncRNAs (long non-coding RNAs) with insulin resistance, accelerated senescence, and inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Hum Genomics. 2018;12:41. doi: 10.1186/s40246-018-0173-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y, Wu F, Zhou J, Yan L, Jurczak MJ, Lee HY, Yang L, Mueller M, Zhou XB, Dandolo L, et al. The H19/let-7 double-negative feedback loop contributes to glucose metabolism in muscle cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:13799–13811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding GL, Wang FF, Shu J, Tian S, Jiang Y, Zhang D, Wang N, Luo Q, Zhang Y, Jin F, et al. Transgenerational glucose intolerance with Igf2/H19 epigenetic alterations in mouse islet induced by intrauterine hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2012;61:1133–1142. doi: 10.2337/db11-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Wu H, Wang F, Ye M, Zhu H, Bu S. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 expression in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:164–169. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.