Abstract

This study investigated how touchpoints moderate the antecedents of customer satisfaction with service encounters by comparing online and in-store encounters. Construal level theory was used within the Touchpoint, Context, Qualities (TCQ) Framework (De Keyser et al., 2020) to integrate a comprehensive model of how touchpoints—websites or stores—influence the magnitude of customer responses to qualities of service encounters. A hierarchical linear model (HLM) was estimated using survey data describing the service encounters of 2.4 million customers with a global retailer. Online customers weighed cognitive and behavioral qualities more heavily than in-store customers, whereas they weighed emotional and sensorial qualities less heavily. Moreover, random effects in the HLM model indicated that each country and store would have unique clientele effects for specific qualities. Since each firm has limited resources, this research offers guidance on key qualities in designing satisfying service encounters for each touchpoint and how qualities should be standardized and customized in global omnichannel environments.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11747-021-00808-9.

Keywords: Service, Strategy, Encounters, Relationship, Retailing, Satisfaction, Experience, Touchpoints, Multichannel, Context

Customers often interact with firms using multiple touchpoints, thereby challenging firms to create integrated and favorable service encounters (SEs) for diverse customers across different touchpoints (Sousa & Voss, 2006). Researchers have built on Shostack’s (1985, p. 243) definition of a SE as “a period of time during which a consumer directly interacts with a service.” Today, SEs include diverse customer-firm interactions: actions, communications, and processes, including information-seeking and problem-solving. With the proliferation of technological options, marketers are interested in all interfaces and interactions between firms and their customers (De Keyser et al., 2020; Grewal et al., 2020b; Homburg et al., 2017). Consequently, firms seek to co-create value with customers at various touchpoints—stores, websites, and self-service kiosks—in order to yield satisfying SEs (Singh et al., 2017).

Managers design and manage SEs at each touchpoint (Bleier et al., 2019) to co-create value with customers in efficient and effective ways (e.g., Eroglu et al., 2001). Theoretical and empirical work suggests that customers respond differently to their experiences depending on whether they take place on a website or in a store (Burke, 2002; Noble et al., 2005; Verhoef et al., 2009). Thus, managers are challenged to ensure that all touchpoints are integrated, effective, and thematically consistent (Kuehnl et al., 2019). Today, marketers wrestle with the challenges of new technology, tools, and visual displays to effectively connect with customers (Grewal et al., 2017; Kahn, 2017). Firms need to account for contextual factors when designing SEs (Patrício et al., 2018), but they lack guidance on how qualities of SEs should be customized for touchpoints and markets.

The purpose of this study is to understand how touchpoints moderate the effects of the experiential qualities of SEs on customer satisfaction. First, we investigate how two touchpoints—website and store—influence how customers weigh experiential qualities (e.g., ease-of-use or attractiveness), in evaluating satisfaction with the service encounter. Contrasting the two touchpoints could yield important insights that would be difficult to grasp by studying one independently. Second, we examine the robustness and stability of customers’ responses to experiential qualities across touchpoints to assess how firms should customize their marketing programs and SEs for various markets. By focusing on touchpoints, we contribute to research on service design and customer experience (CX) management as a key source of competitive advantage (Homburg et al., 2017; Verhoef et al., 2009).

Our findings offer four major contributions regarding the design of SEs at different touchpoints. First, a CX perspective requires firms to attend closely to the contextual factors—individual, social, market, and environmental—that moderate the effectiveness of marketing decision variables at a given touchpoint (De Keyser et al., 2020). We study the touchpoint as a key moderator of the effects of experience qualities on customer satisfaction with the SE. This approach to CX management is consistent with differentiated marketing strategies for services (Bharadwaj et al., 1993). We found that customers weighed more heavily the sensory and emotional dimensions of CX during in-store SEs and cognitive and behavioral dimensions during online SEs. The magnitude of the fixed effects of different experience qualities can be very different. Moreover, our hierarchical linear model detected random effects at both the country and store levels, suggesting that the customization of SEs will be more complex because the qualities of SEs are not weighed equally at different touchpoints or in different markets. By identifying the moderating effects of the touchpoint, our paper provides guidance for blending the standardization and customization of SEs in global omnichannel environments.

Second, prior research has typically studied the qualities controlled by the firm, such as merchandise assortment, and their effects on customer satisfaction. In contrast, this study develops a theory-based model to describe how touchpoints moderate the effects of many experiential qualities in the formation of customer satisfaction. Following the Touchpoint, Context, Qualities (TCQ) framework introduced by De Keyser et al. (2020), we develop a comprehensive theory-based model of how customers respond to five dimensions of CX—cognitive, emotional, sensorial, behavioral, and social—across two major touchpoints: websites and stores. We provide an empirical assessment of how different TCQ combinations (focused on touchpoints) influence customer satisfaction with the SE. According to De Keyser et al. (2020), the existing research has ignored market and environmental factors. To answer this call, this study provides a strong test of the moderating role of touchpoints for five dimensions of CX while controlling for individual, social, market, and environmental factors.

Third, we introduce construal level theory (CLT; Fiedler, 2007; Trope & Liberman, 2010) as an integrative perspective on how customers evaluate their satisfaction with SEs at different touchpoints. It helps explain the moderating effects of websites versus stores on the five CX dimensions on customer satisfaction with SEs. CLT provides a foundation for predictions about how different experiential qualities of the SE are moderated by touchpoints in distinct ways. For example, website customers weigh more heavily cognitive discrepancies from the (first-established) store touchpoint because it is a concrete and proximal referent. It also explains why customers weigh sensorial qualities more heavily when they align with the central features of the (concrete) store touchpoint. Our research shows that CLT can provide an integrative mechanism to explain why there are differences in how consumers experience SEs at different touchpoints, thereby stimulating future research on CX.

Fourth, given the pervasiveness of the multichannel environment, Bitner and Wang (2014) called for studies of qualities of SEs across multiple touchpoints. The current study considers a common situation in which a firm first established stores as touchpoints—serving as the customer’s primary reference point—and subsequently added online channels. We focus on qualities of SEs that are of relevance to most touchpoints and firms and proceed to analyze an extremely rich database. Our study is the first of its kind as it does not look at variables and moderators in isolation; it analyzes the moderating effects of the touchpoint (website versus store) in the presence of all other contextual descriptors. This research design ensures that our insights about the customization of SEs at touchpoints are relevant to most touchpoints, firms, and regions; it also reveals variation in the importance of experience qualities across different markets. Based on these insights, we offer implications regarding omnichannel design and investments in specific touchpoint technologies that support SEs.

Next, the paper reviews the relevant literature and describes our integrative conceptual framework based on CLT (Trope & Liberman, 2010). We then develop hypotheses about the moderating effects of touchpoints (website and store) on CX qualities and their influence on satisfaction with the SE. We test the hypotheses with data from a well-known global retailer’s customer surveys about a recent SE through its website or store in 47 countries, which yielded 2.4 million observations. Since our model examined a single service firm operating in multiple markets with roughly identical offerings, we obtained robust findings on whether the effects of the qualities of SEs were larger or smaller, depending on the touchpoint, after controlling for contextual factors. We estimate a hierarchical linear model (HLM) that incorporated fixed and random effects and considered that customers are nested within websites or stores, which are themselves nested within countries. The model’s (fixed) interaction effects captured how touchpoints moderate the effects of CX qualities on satisfaction with SEs. Our findings provide theory- and results-based guidance on how to create satisfying SEs for websites and stores.

Service encounters across touchpoints

An early view of the SE focused on the dyadic interaction between a customer and a frontline employee at a service provider (Solomon et al., 1985). Today, the context in which SEs take place is often technology-enabled, with the SE unfolding both online and in the physical servicescape (Bolton et al., 2018; Grewal et al., 2020a; Ostrom et al., 2015). Recently, it was posited within the TCQ framework that there are three building blocks of CX in SEs (De Keyser et al., 2020). First, a SE takes place at a touchpoint or point of interaction between the customer and the brand/firm. Second, CX qualities (i.e., attributes) corresponding to the five CX dimensions reflect the nature of customer responses to SEs. Third, these experiences are influenced by the context, that is, situationally available resources at the touchpoint. According to De Keyser et al. (2020), linking qualities to evaluative judgements of the SE is a key issue in CX research that captures its multi-dimensional nature.

Omnichannel research and service touchpoint design

Neslin and Shankar’s (2009) review article identified five steps in multi-channel customer management: customer analysis, multi-channel strategy development, channel/touchpoint design, implementation, and evaluation. Marketers have typically focused on two steps: customer analysis, especially studying the research shopper (e.g., Verhoef et al., 2007), and multi-channel strategy development, such as showrooming and webrooming (e.g., Jing, 2018). Omni-channel strategies—which require touchpoint integration—are necessary for retailers to create seamless CXs (Kumar et al., 2019a, 2019b; Verhoef et al., 2015) and leverage channel synergies (Kumar et al., 2019a). However, few studies have investigated the design step, especially for SEs within omni-channel environments. Rather than studying specific qualities and service design, some studies have compared online and offline preferences (e.g., Hult et al., 2019). In a conceptual article about customer engagement, Kumar et al., (2019a, 2019b) argued that retailers should focus on moderators in order to ensure consistency and favorable SEs, thereby enhancing CX. Studies that focus on the design of SEs as part of touchpoint integration are scarce. Table 1 summarizes relevant studies of both websites and stores.

Table 1.

Studies comparing website and store service encounters

| Authors | Study Context | Sample | Theory | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burke (2002) | Online panel | n = 2,120 | None mentioned | Frequencies and percentages of behaviors and opinions |

| Shankar et al. (2003) | Two studies of the lodging industry | n1 = 144; n2 = 272 | Prospect theory | Dependent variable: loyalty. The relationship between satisfaction and loyalty was stronger for the website than the store. In particular, easy-to-obtain information had a stronger effect on satisfaction for the website than the store |

| Noble et al. (2005) | Survey data from a nationwide random sample of consumers | n = 754 | Rational choice theory under uncertainty, whereby customers maximize subjective expected value (perceived benefits and costs) during goal-directed activities (Tellis & Gaeth, 1990) |

Dependent variable: self-reported channel utilization Main effects: Utilitarian values of information attainment, price comparison, possession, and assortment-seeking influence self-reported channel utilization across brick-and-mortar, catalog, and online retail channels |

| Frambach et al. (2007) | Face-to-face interviews with potential home mortgage purchasers | n = 300 | Rational choice theory under uncertainty, whereby customers maximize subjective expected value (perceived benefits and costs) during goal-directed activities |

Dependent variable: intention to use a website versus representative Moderating effect of purchase stage: Customers in pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase stages weighed perceptions of channel (e.g., ease-of-use) differently when formulating their intentions to use the website versus service representative (mortgage advisor) to obtain a mortgage |

| Van Birgelen et al. (2006) | Survey data from a retail bank | n = 1,966 | Use the appraisal-emotional response-coping framework (Bagozzi, 1992) | Dependent variable: business-to-business purchase intentions. It identified how satisfaction with employees and the website influence the behavioral intentions of firms and estimated the model for routine and non-routine services |

| Hammerschmidt et al. (2016) | Survey of store and website shoppers of a grocery retailer | n = 731 | Structural alignment of attributes theory from the judgment and decision-making literature |

Dependent variable: satisfaction with the touchpoint: store and website Main effects: The study identified five facets that are consistent across touchpoints: choice, charge, convenience, confidence, and care |

| Hult et al. (2019) | Survey data from ACSI on retailing | n = 913 | Utility functions that account for acquisition utility and transaction utility |

Dependent variable: customer satisfaction with purchases Moderator effect of touchpoint: perceived quality and expectations had a larger effect on satisfaction with in-store purchases; value had a larger effect on satisfaction with website purchases |

| Present Study | Online survey of consumers | n = 2,400,000 | Touchpoint, context, qualities (TCQ) framework and construal level theory | The results showed that, in evaluating service encounters, customers who visited the organization’s website weighed the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of customer experience more heavily than customers who visited the store. In contrast, customers who visited the organization’s stores weighed the sensorial and social dimensions of customer experience more heavily |

Main effects of CX qualities on evaluations of SEs at different touchpoints

Field studies have shown that CX qualities (e.g., ease of transactions, quality assortment of merchandise, and atmosphere) directly influence customers’ preferences for utilizing stores, websites, or catalogs (Baker et al., 2002). Most of these studies have examined a single touchpoint, primarily stores (Baker et al., 2002; Verhoef et al., 2009) or websites (Bleier et al., 2019; Mathwick et al., 2002), with the exception of Burke’s (2002) web-based study of customer perceptions of website and in-store shopping, which explored what shoppers want in both online and in-store environments. Frambach et al. (2007) compared pre-purchase, purchase and post-purchase stages and found that customers weighed qualities differently when forming their intentions to use a website versus a traditional bank branch. Shankar et al. (2003) and Van Birgelen et al. (2006) showed that touchpoint satisfaction moderated the relationship between overall satisfaction and loyalty. Finally, Hult et al. (2019) compared website and store shoppers’ satisfaction with purchases across a range of service industries.

There is, however, limited evidence of moderator effects across websites and stores. What is usually researched is a single quality in a single market. For example, easy-to-obtain information has a larger effect on satisfaction delivered by a website versus a store (Shankar et al., 2003); perceived price fairness has a stronger effect for store shopping than website shopping (Hammerschmidt et al., 2016). There are no studies comparing customers’ satisfaction with website and store SEs that provide a theoretical rationale concerning why their effects differ, describe empirical regularities for multiple qualities for multiple CX dimensions across markets, and offer managerial implications. Importantly, both Verhoef et al. (2009) and De Keyser et al. (2020) proposed that contextual or situational variables are important moderators in the formation of customer assessments of their experiences, but they did not study them empirically. These knowledge gaps are surprising because CX researchers have argued that the magnitude of the effects of SE qualities depends on the customer’s context.

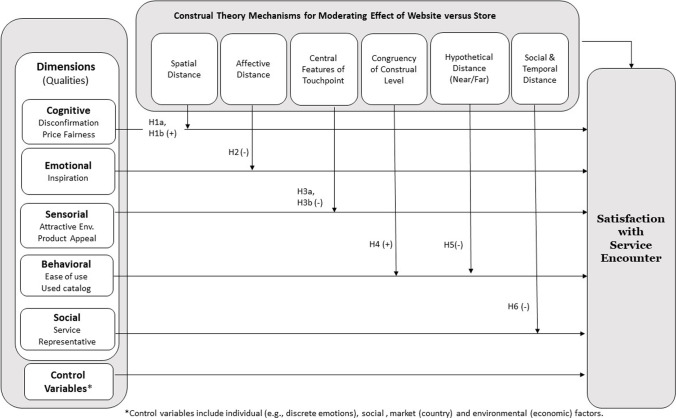

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

Drawing on CLT, we build on the TCQ framework (De Keyser et al., 2020) to develop and test a theory-based conceptual framework of how customer touchpoints (website or store) moderate the effects of qualities in forming customer satisfaction evaluations about SEs. In our conceptual framework in Fig. 1, the left side shows the main effects of experience qualities on customer satisfaction with a SE. Across the top, we distinguish underlying psychological distances drawn from CLT that create the moderating effects of touchpoints. The hypotheses concerning how the touchpoint moderates qualities are depicted by the arrows. While this framework incorporates the main effects of qualities on customer satisfaction, our paper focuses on the moderating effects of the touchpoint (website versus store). We control for the service brand and context, including individual, social, market, and environmental factors, as shown at the bottom of Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework

To enhance our study’s generalizability, we focus on the qualities of each CX dimension that are well established in prior research and relevant to SEs for many firms (Homburg, Jozic, and Kuehnl 2017). We study how the touchpoint moderates eight qualities corresponding to the five CX dimensions identified in the TCQ framework (De Keyser et al., 2020): cognitive (favorable disconfirmation, price fairness), emotional (inspiration), sensorial (attractive environment, product appeal), behavioral (ease-of-use and catalog use), and social (service representative). In prior research, the main effect of each quality has been widely acknowledged as a predictor of customer SE satisfaction in relation to both websites and stores (e.g., Shankar et al., 2003). For example, an attractive website or store influences customers’ touchpoint usage and satisfaction (Kaltcheva & Weitz, 2006). This section summarizes CLT and develops theory-based hypotheses about the moderating effects of touchpoints on the eight qualities of SEs. Since CLT is still under development, it integrates most (but not all) prior work concerning the judgment and decision-making underlying our hypotheses.

Construal level theory

We draw upon CLT to build an integrative model of customer satisfaction with the SE at a given touchpoint (Trope & Liberman, 2010; Trope et al., 2007). CLT posits that people perceive events that vary according to types of psychological distance from the self (here and now): spatial distance, affective distance, hypotheticality (i.e., the likelihood of an event occurring), social distance, and temporal distance. Psychological distance affects how concrete or abstract people’s thoughts are. When an event is psychologically distant (distal), people engage in high-level construal, which refers to abstract thought. When an event is psychologically close (proximal), people engage in low-level construal, which refers to concrete thoughts. For example, "warm" emotionally charged photos of an object are less psychologically distant than "cold" text descriptions of the same object (Fiedler, 2007). Also, a hypothetically near event is one that is highly probable, whereas a hypothetically distant event is one that is highly improbable (Liberman et al., 2007a, b). Highly likely events will be processed at low-level construals, and highly unlikely events will be processed at high-level construals. At high-level construals, people think about the gestalt and focus on central features, not details. At low-level construals, people think more concretely about secondary features and details. It is easier for customers to process mental representations that are congruent, that is, at the same construal level. The construal level influences people’s interpretation and evaluation of their experiences (see different CLT mechanisms across the top of Fig. 1). There are only a few applications of CLT to SEs or touchpoint design (e.g., Ding & Keh, 2017).

Fiedler (2007) observed that CLT provides an integrative framework for explaining a wide variety of judgment and decision-making phenomena across different domains, including preference reversals. Liberman et al., (2007a, b) speculated that psychological distance (especially spatial distance) may explain customers’ responses to Internet shopping experiences, an issue that we investigate in this paper. We consider how customers’ interpretation of website and store SEs are inference-based, potentially drawing on their prior knowledge and experience, which is psychologically distant from the particular SE and moderated by secondary features (Fiedler, 2007; Verhoef et al., 2009). Many SE qualities are associated with each CX dimension and they may have different construal levels. Below, we summarize prior research concerning the main effects of the qualities of the SE that correspond to each of the five CX dimensions. We then discuss the theoretical mechanisms for the moderating effect of the website or store on each quality that influences customer satisfaction with a SE.

Cognitive qualities and spatial distance

Service research has established that people do not necessarily respond to discrete elements of a SE but, rather, to their total configuration (Roschk and Hosseinour 2020). We believe that the first and well-established touchpoint is likely to serve as a primary (holistic) reference point for customers during a SE. For example, customers’ primary referent for Amazon is its website, whereas their primary referent for Walmart is its store—although both firms serve customers through both touchpoints. When a customer’s primary referent is the store and they visit the firm’s website, the SE takes place at a greater spatial distance than during the store visit (Fiedler, 2007; Liberman et al., 2007a, b). Spatial distance is also greater because websites serve customers in a large geographic region, whereas stores serve customers in a (smaller) trading area. Since the website (store) is spatially distant (proximal), customers will rely on an abstract (concrete) construal process (Darke et al., 2016). In this paper, we begin by discussing how the touchpoint moderates two holistic (abstract) qualities of the cognitive dimension of CX—favorable disconfirmation and price fairness—due to spatial distance.

Holistic favorable disconfirmation

An important cognitive ingredient of satisfaction is overall expectancy-disconfirmation: the customer’s comparison of their perceptions with expectations or prior beliefs about the service brand (Oliver, 1997). Our survey follows common practice and measures it at the holistic level rather than the attribute-specific level, labelling it favorable disconfirmation. The main effect of this construct has been well established from decades of customer satisfaction research; satisfaction is high when customers perceive that service is better than expected. Customers’ perceptions of SE qualities are influenced by their congruency with prior holistic beliefs, which serve as a reference point (Bosmans, 2006). The elicitation of holistic favorable disconfirmation regarding a website SE will evoke an abstract construal process that highlights overall discrepancy or fit (Kim & John, 2008). In contrast, a store SE leads to concrete mental construal arising from the customer’s knowledge and experience about the primary referent (Hamilton & Thompson, 2007). In this study, the primary referent for the cooperating firm is its store, so we believe that the effect of favorable disconfirmation on customer satisfaction with the SE will be larger when they visit the website than when they visit the store.

H1a

When the firm’s first established touchpoint is the store, customers who visit the website will weigh favorable disconfirmation more heavily than customers who visit the store (positive moderating effect).

Holistic perceptions of price fairness

There is a well-established main effect of price fairness on customer satisfaction; the customer’s perception of price fairness is an important cognitive ingredient of satisfaction (Oliver, 1997). With respect to moderating effects, pricing research has shown that the nature of the decision task influences the importance of price. For example, since price information produces precise and easy-to-compute comparisons, it is relatively less important in overall evaluations than comparison-based tasks (Nowlis & Simonson, 1997). A CLT explanation is that evaluations and preference formation weigh more heavily on (future) desirability, whereas choice tasks weigh more heavily on (current) feasibility (Liberman & Trope, 1998; Sagristano et al., 2002).

A customer’s holistic perception of price fairness will not be the same for SEs at two different touchpoints because he/she is exposed to different information displayed in different formats. From a CLT perspective, price fairness or judgments of equity (Oliver, 1997)—unlike perceptions of price information—entail abstract (high level) mental representations that do not require immediate self-identification (Fiedler, 2007). Since a website SE takes place at a greater psychological distance than a store SE (Darke et al., 2016), the (distal) website reinforces an abstract construal of price fairness in customers’ overall SE satisfaction. These observations suggest a moderating effect that reconciles conflicting empirical findings; namely, customers evaluating website SEs will weigh price fairness more heavily than those evaluating store SEs due to the more abstract mental representations and high construal level of the former.

H1b

Customers who visit the website will weigh price fairness more heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store (positive moderating effect).

Note that, if we studied a quality of the cognitive CX dimension that is construed at a low (concrete) level, we would expect a prediction in the opposite direction.

Emotional qualities and affective distance

The retailing literature has long recognized the main effects of consumers’ perceptions of utilitarian and emotional (i.e., hedonic) qualities on customer satisfaction with store and website SEs (e.g., Childers et al., 2001; Chitturi et al., 2008). This literature stream distinguishes between qualities that yield utilitarian versus emotional value, thereby satisfying different motives. Fiedler (2007) has argued that affective distance is related but conceptually distinct from other distance dimensions where “warm” events are more proximal. Following this view, we consider emotional qualities to decrease affective distance where affect includes valence (pleasant/unpleasant) and arousal. Septianto and Pratiwi (2016) have shown that consumers with low-level construal evaluated an ad with an emotional appeal more favorably than an ad with a utilitarian appeal. Their study supports the notion that emotional (utilitarian) qualities are concrete (abstract) and proximal (distal) and are associated with a small (large) affective distance, such that consumers process these mental representations with low-level construal.

Since the website is spatially distant relative to the store, customers’ mental representations will be evaluated at a high construal level. However, CLT argues that different facets of psychological distance (e.g., affective distance) can compensate for another facet (e.g., spatial distance). We believe that this notion is very likely to be true when customers evaluate their SEs both on websites and in stores. Emotional qualities will reduce the psychological distance between the customer and the touchpoint so that they weigh these emotional qualities with a low construal level. Customers will rely on abstract (high) level construal and, consequently, weigh (concrete) emotional qualities less heavily in forming satisfaction with SEs through websites versus stores. In this study, emotional quality is represented by an affective measure, inspiration, which has both favorable valence and a high arousal level (Böttger et al., 2017). In particular, the cooperating firm promises that its brand provides inspiration and offers novel solutions. Customers’ perceptions of this emotional message lead to the following hypothesis:

H2

Customers who visit the website will weigh the affective dimension (i.e., emotional qualities)—such as inspiration—less heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction than customers who visit the store (negative moderating effect).

We distinguish affective measures of emotional qualities from discrete emotions (Kranzbühler et al., 2020) because Liberman et al., (2007a, b) consider discrete emotions to be self-related CLT outcomes rather than a distance dimension. Thus, H2 focuses on affect (inspiration). However, we investigate the potential moderating effects of the website on discrete emotions in our empirical work without proposing a parallel hypothesis.

Sensorial qualities and central touchpoint features

According to CLT, an event is psychologically distant when it is not part of the customer’s direct experience (e.g., primarily intangible and lacking in sensorial qualities). The services literature has emphasized that the intangible nature of services (versus goods) directly influences customer SE satisfaction, in addition to the tangible qualities that engage all five senses. Since website SEs only engage sight and sound, sensory information is less available and reliable (Bosmans, 2006), thus creating informational distance (Ding & Keh, 2017; Fiedler, 2007). A website can offer pictorial or text descriptions of haptic information, such as the softness of a fabric, but it is psychologically distant and less reliable than directly touching the fabric in a store (Elder et al., 2017). E-commerce research has typically studied intangible SE qualities such as efficiency, fulfillment, system availability, and privacy (e.g., Parasuraman et al., 2005). In laboratory and field studies, customers have relied on intangible qualities in forming their service evaluations under an abstract (high) construal level and tangible, sensorial qualities under a (low) concrete construal level (Ding & Keh, 2017; Elder et al., 2017). Thus, intangible SE qualities evoke abstract construal, whereas sensory qualities are proximal and evoke concrete construal.

In considering a moderating effect of the touchpoint, people will use broader categories to classify objects for (distal) website SEs than (proximal) store SEs (Trope & Liberman, 2010). Prominent visual cues and location effects, which are central features, moderate customers’ preferences (Kahn, 2017; Liberman et al., 2007a, b; Trope & Liberman, 2010). A CLT perspective on structural alignment theory indicates that, when a SE takes place at a store rather than on a website, sensorial cues will be more salient and easier to process (Sun et al., 2019). Thus, we predict that customers will rely on abstract (high) level construal and weigh sensorial qualities less heavily in forming satisfaction with a website SE than customers evaluating a store SE. We study two well-established sensorial qualities that are common to websites and stores in order to test this hypothesis (Ganesh et al., 2010). First, website aesthetics are analogous to in-store atmospherics (Wang et al., 2011)—we call this sensorial quality attractive environment. Second, merchandise or product appeal influences retail preferences (Simonson, 1999). Both are part of the service brand promise made by the cooperating retailer.

H3

Customers who visit the website will weigh the sensorial dimension of CX—such as (a) attractive environment and (b) product appeal ─ less heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store (negative moderating effect).

Behavioral qualities

We consider two behavioral qualities: ease-of-use and use of the catalog. Different facets of CLT explain the moderating effects of the touchpoint for these two behavioral qualities. The moderating effect of the touchpoint on ease-of-use can be explained by the congruence of the touchpoint and the construal level (Zeithaml et al., 2002). In contrast, the moderating effect of the touchpoint on the customer’s use of a catalog influences psychological distance by reducing hypotheticality. We believe that these two distinct mechanisms explain why the direction of the moderating effects of the touchpoint differ for these two qualities.

Ease-of-use: Congruency

Ease-of-use in navigating a website or store is a quality associated with the behavioral dimension of CX that influences touchpoint usage and satisfaction (Montoya-Weiss et al., 2003; Noble et al., 2005). It is a high-level mental representation of an event (Trope & Liberman, 2010) that is especially relevant to SEs through websites and stores (Zeithaml et al., 2002). E-commerce research has shown that the task–technology fit is positively related to customers’ perceptions of websites as being easy to use (e.g., Klopping & McKinney, 2004), where ease-of-use influences overall evaluations of SEs (e.g., Goodhue & Thompson, 1995) and subsequent behavior (e.g., Fisher et al., 2019; Rose et al., 2012; Weijters et al., 2007). Ease-of-use is also relevant in store SEs (Shankar et al., 2003), where ease of navigation and interaction with the store environment—including store layout, information availability, atmospherics, and service convenience—create a satisfying SE (Berry et al., 2002).

CLT emphasizes that it is easier for customers to process mental representations that are congruent, that is, at the same construal level. Thus, the construal level is an important moderator of the antecedents of customer evaluations (Cho et al., 2013). Customers’ (distal) mental representations of website SEs will be at the same construal level as ease-of-use—a high (abstract) level—and, consequently, more relevant, salient, and easier to process in forming a satisfaction judgment. For this reason, we expect that customers engaged in evaluating website SEs will weigh ease-of-use more heavily than those evaluating store SEs.

H4

Customers who visit the website will weigh ease-of-use more heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store (positive moderating effect).

Catalog use: Hypotheticality

Customers can consult the retailer’s catalog before or during a SE at the store or on the website. Catalog use has a favorable main effect on customers’ subsequent purchase behavior in stores and on websites (e.g., Verhoef et al., 2007). This retailer’s catalog is extremely effective in co-creating value beyond its product presentations (similar to a Patagonia catalog). From a CLT perspective, a key feature of catalogs is their vividness—defined as that which is temporally proximal, physically proximal, or emotionally appealing. In retailing, vividness is often evaluated in terms of the quality of product presentations (Jiang & Benbasat, 2007). It enhances customer involvement, imagery, and elaboration (Nisbett & Ross, 1980) and increases the likelihood of message-based persuasion (Smith & Shaffer, 2000), leading to enhanced retail sales (Grewal et al., 2020b). Vivid catalogs can depict products in future consumption contexts, reducing their hypotheticality so they seem more likely to occur (e.g., a family relaxing on patio furniture). Stores use technology and displays to convey rich information about consumption opportunities (Grewal et al., 2020a, 2020b). Displaying a product in a dynamic (versus static) visual format enhances information vividness, which increases consumer preference (Roggeveen et al., 2015). Thus, catalog use should make the consumption opportunity hypothetically near such that it is construed at a low level (Liberman et al., 2007a, b).

Kim and John (2008, p. 118) argued that construal levels influence evaluations through a “preference for information, experiences or events that match the individual’s abstract or concrete mindset.” Hence, the moderating effect of a touchpoint on catalog use should be larger for the congruent touchpoint (i.e., with the same construal level). Both print catalogs and websites rely heavily on pictorial and verbal representations; therefore, there is congruency in the presentation medium and sensory information (Trope & Liberman, 2010, p. 457; Trope, Liberman et al., 2007a, b, p. 87). However, Griffith et al. (2001) have shown that customers’ perceptions of print catalogs can only compare favorably with low-fidelity website experiences. The vividness of product presentations in SEs through stores and catalogs ensures that these depictions are perceived as hypothetically near; as such, they will be processed at a low level construal. Thus, catalog and store SEs are more congruent than catalog and website SEs. Catalogs and stores present products in vivid ways that reduce hypotheticality and increase preference for the displayed products. Hence, we predict that catalog SEs will be weighed less heavily for customers visiting websites versus stores.

H5

Customers who visit the website will weigh catalog use less heavily in evaluating their current SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store (negative moderating effect).

Social qualities: Service representatives and social distance

In retailing studies, prior encounters with customer service representatives typically have a negative main effect on customer satisfaction (Bolton & Drew, 1991). The reason is that the customer often interacts with the representative to resolve a problem, which is an unfavorable event. For this retailer, customer service requests require a telephone interaction between a customer and an employee. This feature is distinctive because the retailer’s store and website place heavy emphasis on self-service. (Employees are most evident in the store at checkout.) Therefore, we consider a prior interaction with a customer service representative as reflective of a social CX dimension. CLT emphasizes that social distance is related to the influence of psychological distance on mental construal level and evaluations (Trope & Liberman, 2010).

Kuehnl et al. (2019) argue that retailers can design effective customer journeys by enhancing customers’ perceptions that touchpoints are thematically cohesive and consistent, in a context-sensitive way. In two empirical studies, the authors provide evidence that a thematically cohesive and consistent customer journey has a favorable effect on customer loyalty through brand attitude over and above the effects of brand experience. They posit that the procedural aspects of CX are more concretely construed whereas outcome aspects of CX are more abstractly construed. Their work points to the question of whether the concrete procedural aspects of the CX involving a service representative is consistent with a store SE, a website SE, or both. Store SEs are often social; customers interact with other customers as well as employees. For website SEs, customers sometimes interact with online service representatives or chatbots (i.e., automated social presence), but the CX for these SEs is spatially remote and partially automated. For this retailer, interactions with a customer service representative are more procedurally consistent with the store SE than with the website SE. As such, we predict that the effect of prior service representative interactions will be smaller for customers’ evaluations of website SEs versus store SEs.

H6

Customers who visit the website will weigh a prior interaction with a service representative less heavily in evaluating their current SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store (negative moderating effect).

As the above discussion indicates, CLT does not provide a clear-cut prediction regarding prior interaction with a customer service representative because multiple mechanisms may be at play. Interactions with a service representative in a telephone call center (often regarding a failure or problem) are highly distinctive in many ways and they take place in the past. Given spatial, social, and temporal distance, it is highly possible that a prior interaction with a service representative will have little effect on subsequent SEs at any touchpoint.

Model specification for satisfaction with service encounters

The preceding discussion developed predictions about how the touchpoint moderates eight qualities that influence customer satisfaction with a SE (see Fig. 1). These considerations yield the following general model for customer satisfaction with a SE, where Web is a dichotomous variable that indicates whether or not the SE occurred online. The interaction terms represent our hypotheses in the order introduced.

| 1 |

Our model will also incorporate covariates to control for contextual factors, which is explained in the next section. Thus, Eq. (1) includes vectors of individual customer descriptors, such as goals and loyalty program member; factors, such as country-specific random effects; factors, such as store clientele effects; and factors, such as housing.

Study context, data and methodology

To operationalize and estimate our model, we obtained survey data from a cooperating retailer that operates websites and stores in 47 countries across North America, Europe, and Asia. The retailer sells home décor, furnishings, accessories, and related services that bear its global brand name. It has an established position as a value store brand (i.e., good quality for low prices) in the global marketplace. The firm promises that visiting the store is an engaging experience for the whole family and includes, food, product design, and new ideas to bring home. By studying a single global retailer, we controlled for numerous marketing variables.

Survey data

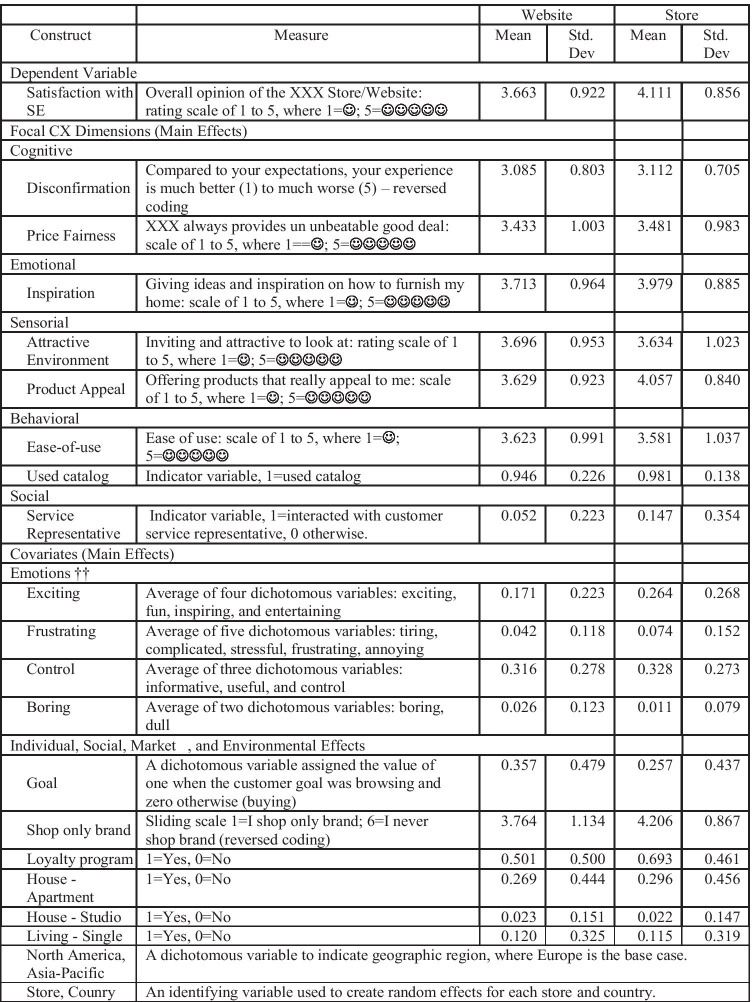

The retailer conducted an online survey of people who have experienced a SE in the past three months. It drew samples for each website and store in each country, using an identical methodology upon their visit to the website. The retailer provided quarterly survey data from the last quarter of 2010 through the spring of 2014. Each customer was included in the analysis once and randomly assigned to a touchpoint they visited in the last three months. From the 2.4 million responders, 2.2 million or 91% had no missing values for the variables of interest and were included in the analysis. The survey respondents were 79% female; 64% were between 25 and 50 years old; and 60% had enrolled in the company’s loyalty program (see descriptive statistics in Table 2). We compared the characteristics of this sample of customers with those of an independent sample of the retailer’s customers who were surveyed by telephone. The comparison showed no significant differences across samples for age, gender, income, and number of times the customer had visited the retailer’s store. Hence, the online method of data collection used in this study does not seem to have affected the representativeness of the sample.

Table 2.

Constructs, measures, and descriptive statistics†

†There is also a dichotomous variable representing the touchpoint, where Web = 1 for a website SE and 0 for a store SE. Interactions are not shown. ††The survey included an emotions inventory of 14 items used to develop the emotions indices. See Web Appendix

The retailer’s survey measured all eight qualities using identical questionnaire items for both touchpoints across all countries. For example, website and store aesthetics were measured through the same survey item, “inviting and attractive environment,” and ease of navigating the website or store was measured through the item “easy-to-use.” It also used the same pictorial response scale, smiley faces, in all countries, except that favorable disconfirmation was measured using the better/same/worse scale (typical in satisfaction research). Prior research has shown that adding smiley faces to scales in online satisfaction survey reduces the time respondents spend reading the question without changing the distribution of responses (Stange et al., 2018). The Web Appendix Part A shows the results of a separate online study. In it, Table W3 shows that these measures (with the exception of catalog and service representative, which we did not attempt to replicate) corresponded to the distinct and independent underlying factors identified through principal components analysis. The Web Appendix also provides additional information on methodological issues: (1) the robustness of smiley scales, (2) the dimensions of CX and associated measures, and (3) the replicability of key moderating effects and the magnitude of the effect sizes.

Model operationalization

The equations for SE satisfaction were comprehensive; they included predictor variables used in prior research on customer satisfaction in a retail setting (e.g., Baker et al., 1992; Oliver, 1997). The predictor variables included the eight qualities and 17 covariates when the interaction terms were included. We created a dichotomous variable, web, which took on the value of one for customers who visited the website and zero for customers who visited the store. We created interaction terms to test our hypotheses by multiplying each of the eight qualities by the web variable. Since we allowed for random effects for country and store for all experiential qualities, there were a total of 46 parameters. The following paragraphs briefly explain the theoretical rationale for the inclusion of the covariates, shown in the bottom half of Table 2.

Emotions

In addition to controlling for the main effects of emotions, we will investigate whether the website or store has a moderating effect on discrete emotions. The cooperating retailer’s survey captured 16 discrete emotions, with a dichotomous self-report measure indicating whether or not the emotion was present. A principal component analysis, as described in the Web Appendix Part B, showed that 14 of the emotion variables consistently loaded on four factors as follows:

Frustration included five items: complicated, stressful, frustrating, tiring, and annoying

Boredom included two items: boring and dull

Control included three items: informative, useful, and functional

Excitement included four items: exciting, fun, inspiring, and entertaining

We performed principal components analyses of emotions for different samples by country, touchpoint, and by pooling all the data. The factor loadings were consistent. Since there were no cross-national differences, this finding established measurement invariance for our emotions measures. Instead of using factor scores, we created an index for each of the four underlying emotions by averaging the relevant items. By using an average rather than a sum, each emotion could be measured on the same zero to one scale, which was easily interpretable.

Other covariates

We recall that the model controlled for contextual factors: individual customer descriptors, such as goals and loyalty program member; market factors, such as country-specific random effects; social factors, such as store clientele effects; and environmental factors, such as housing. With respect to individual descriptors, the respondents chose from a list of goals related to buying, browsing, or searching for information or services available. Although customers often make visits with multiple goals in mind, we chose to analyze data from customers who reported that their primary goal was to buy or browse. Below, we elaborate on how we captured country- and store-specific phenomena through fixed and random effects.

Summary

The full model can be written algebraically as follows:

| 2 |

where i represents customer level; j represents store level; k represents country level; β0j and β0k represent random intercepts at the store and country levels, respectively; μ1j and μ1k represent random coefficients at the same levels; Xijk is a vector of variables capturing the main effects of favorable disconfirmation, price fairness, inspiration, attractive, appeal, ease-of-use, catalog, and service representative qualities, consistent with the TCQ framework (De Keyser et al., 2020). W stands for web; Eikj represents the vector of emotions (frustrating, exciting, control, and boring); Rk represents the dummy variables for region (North America and Asia–Pacific); and Sijk represents individual and environmental characteristics such as goal, loyalty behavior, and housing situation (see Table 2). Logically, stores are considered nested within countries (capturing market and social effects), as described below.

Model estimation and results

All variables were mean-centered. The model was estimated using HLM, an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression–based analysis that can take into account that customers are nested within websites or stores, which are nested within countries. We used the Proc Mixed procedure in SAS. The HLM model includes fixed and random effects for the main effects of qualities as well as random intercepts for each level. The random effects capture variation across touchpoints and countries. Level one is at the country level, and it comprises customer characteristics, such as living conditions and loyalty program participation. Level two is the touchpoint, which is nested within the country level. Although the main effects of SE qualities have both fixed and random effects, the interactions with qualities are estimated as fixed effects only because there are insufficient degrees of freedom to treat them as random effects.

These random effects capture two types of variation. First, our survey measures were the same across countries, but customers in different countries could have responded to the scales in different ways. Thus, there was a need to create metric equivalence. Hulland et al. (2018) distinguished among three post-hoc approaches to creating metric equivalence: (1) explicit or implicit control of systematic error depending on whether the source of the bias can be identified and directly measured; (2) correction at the scale or individual item level; and (3) the specification of a single or multiple sources of systematic error with one or more method factors (see also Podsakoff et al., 2003; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff 2012). Hence, in our model, we followed the third approach and controlled for metric differences across country by specifying a country-level random effect. The country-level random effect captured multiple unobserved country-level differences, including cultural differences. Second, for each customer, we knew the store that they had visited, so we incorporated store-specific random effects to capture unique clientele effects.

Model Development and Assessment

We built the model progressively by testing the appropriateness of including a random intercept for the country and store, followed by the fixed and random effects for SE qualities and then the control variables. Last, we included the interactions and tested their significance. Table 3 shows a series of nested model tests. Log likelihood ratio tests established that the following effects were statistically significant at p < 0.05: random intercepts for the country and store levels only, 19 fixed effects at the country level, eight random effects at country and store levels, and eight interactions. The final estimated model is presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Comparisons of alternative HLM models†

| Model | AIC | -2 Log Likelihood | Chi-Square Value | df | Critical Chi-Square (p = 0.05) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No predictors, random intercepts for country and store level only | 6,155,857 | 6,155,849 | Base model; intercepts significant; random model appropriate at country level | |||

| Add 19 fixed effects at country level | 4,323,539 | 4,323,493 | -1,832,356 | 19 | 96,439.8 | Reject null of no fixed effects |

| Add 14 random effects at country and store levels | 4,283,309 | 4,283,239 | -40,254 | 14 | 2875.3 | Reject null of no random effects |

| Add 8 fixed (hypothesized) interaction effects | 4,281,425 | 4,281,331 | -1908 | 8 | 238.5 | Reject null of no hypothesized interaction effects |

| Add 6 fixed interaction effects for regions and discrete emotions | 4,279,246 | 4,279,136 | -2195 | 6 | 365.8 | Reject null of no interaction effects for regions and discrete emotions |

†Each model is compared to the model above it. The chi-square value is the difference between the -2 Log Likelihood values for the two models. The degrees of freedom are the difference in the number of parameters. The final model has 2,189,063 observations

Table 4.

HLM model results†

| Moderating Effects | Coefficient | SE | Hypotheses | |||

| Web × Disconfirm | 0.0291*** | 0.0135 | H1a H1b:( +) Website customers weigh (a) cognition (favorable disconfirmation, price fairness) more heavily | |||

| Web × Price Fairness | 0.0089** | 0.0028 | ||||

| Web × Inspiration | -0.0264*** | 0.0033 | H2:(-) Website customers weigh emotional qualities less heavily than in-store customers | |||

| Web × Attractive | -0.0468*** | 0.0044 | H3a H3b:(-) Website customers weigh sensorial qualities less heavily than in-store customers | |||

| Web × Prod. Appeal | -0.0844*** | 0.0034 | ||||

| Web × Ease-of-Use | 0.1497*** | 0.0039 | H4:( +) Website customers weigh behavioral qualities (ease-of-use) more heavily | |||

| Web × Catalog | -0.0496*** | 0.0072 | H5:(-) Website customers weigh prior service encounters with catalogs less heavily | |||

| Web × Cust. Service | -0.0003 ns | 0.0050 | H6:(-) Website customers weigh prior contacts with service representatives less heavily | |||

| Main Effects | Fixed | Country Random | Store Random | |||

| Coefficient | Standard Err | Coefficient | Standard Err | Coefficient | Standard Err | |

| Intercept | 3.7323*** | 0.0135 | 0.0055*** | 0.0013 | 0.0009*** | 0.0001 |

| Disconfirmation | 0.0594*** | 0.0035 | 0.0003** | 0.0001 | 0.0005*** | 0.0001 |

| Inspiration | 0.0861*** | 0.0034 | 0.0004** | 0.0001 | 0.0002*** | 0.0000 |

| Attractive Env | 0.1714*** | 0.0041 | 0.0005** | 0.0001 | 0.0005*** | 0.0001 |

| Product Appeal | 0.2165*** | 0.0035 | 0.0004** | 0.0001 | 0.0003*** | 0.0001 |

| Price Fairness | 0.0852*** | 0.0027 | 0.0002* | 0.0001 | 0.0002*** | 0.0000 |

| Ease-of-Use | 0.0829*** | 0.0032 | 0.0003** | 0.0001 | 0.0004*** | 0.0000 |

| Service Rep | -0.0529*** | 0.0054 | 0.0009*** | 0.0002 | 0.0003*** | 0.0001 |

| Catalog | 0.1063*** | 0.0086 | 0.0014*** | 0.0005 | 0.0003*** | 0.0001 |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Website | -0.2626*** | 0.0087 | Not Applicable†† | |||

| Browse | 0.0252*** | 0.0010 | ||||

| Discrete Emotions | Not Applicable†† | |||||

| Frustrating | -0.4501*** | 0.0045 | ||||

| Exciting | 0.1250*** | 0.0026 | ||||

| Control | 0.0337*** | 0.0024 | ||||

| Boring | -0.1858*** | 0.0083 | ||||

| Web × Frustrating | -0.2853*** | 0.0078 | ||||

| Web × Exciting | -0.0562*** | 0.0041 | ||||

| Web × Control | 0.0774*** | 0.0035 | ||||

| Web × Boring | 0.1249*** | 0.0100 | ||||

| Market and Demographic Variables | ||||||

| North America | 0.1124 | 0.0550 | Not Applicable†† | |||

| Web × North America | -0.1436*** | 0.0249 | ||||

| Asia Pacific | 0.1227 | 0.0706 | ||||

| Web × Asia Pacific | -0.1617** | 0.0558 | ||||

| Shop Only Brand | 0.0369*** | 0.0005 | ||||

| Loyalty club member | 0.0480*** | 0.0011 | ||||

| House—Studio | 0.0126*** | 0.0031 | ||||

| House—Apt | 0.0204*** | 0.0010 | ||||

| Living Single | -0.0028** | 0.0014 | ||||

| -2 Log Likelihood, AIC (BIC) | 4,279,136 4,279,246 (4,279,348) | |||||

| # of observations | 2,189,063 | |||||

†All predictor variables were mean-centered. †† Binary variables had no random effects ***p < .0001, ** p < .001, *p < 0.01

The model fit was good according to statistical criteria, such as the Akaike information criterion. The fixed main effects of all the predictor variables had the logical sign and were significant at least at p < 0.0001, with the exception of a covariate for living single (p < 0.05). In particular, all five dimensions of CX at the touchpoint—cognition, emotional, sensorial, behavioral, and social—influenced satisfaction with the SE. Also, random effects at the store level were always statistically significant at p < 0.0001, with the exception of catalog (p < 0.01), and random effects at the country level were significant at least at p < 0.01. These random effects indicate that there were small but statistically significant differences in the coefficients of qualities across the countries and stores. We discuss the implications of these effects later. Last, customers who were browsing were characterized by slightly higher levels of satisfaction (p < 0.0001).

Results

The fixed main effect of the website was negative (p < 0.0001), indicating that websites SEs were less satisfying than store SEs. The hypothesis tests of the moderating effects of the touchpoint (website versus store) were captured by fixed effects interaction terms shown at the top of Table 4. In addition to these tests, we replicated the key features of the model with a panel of consumers across firms using data collected by Qualtrics. We tested H1b, H3a and H4 in an online customer survey regarding multiple home goods retailers in one market: the United States. We found the same moderations but with larger effect sizes because the study was conducted for three brands in a single market rather than a single brand across several markets. These results are summarized in Table 5, with more detail in Web Appendix A. A key take-away from this second study is that, beyond replication, the magnitude of the effect sizes can be larger in other study contexts. It also shows that the moderating effects were not an artifact of the time period of the main study.

Table 5.

Summary of findings

| Proposition | Theoretical Mechanism | Findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

|

H1a: When the firm’s first established touchpoint is the store, customers who visit the website will weigh favorable disconfirmation more heavily than customers who visit the store H1b: Customers who visit the website will weigh price fairness more heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store (positive moderating effect) |

Spatial distance. The store, as the first established and proximal touchpoint, serves as the (primary) holistic referent. The website is spatially distant such that (holistic) cognitive dimensions (favorable disconfirmation, price fairness) are weighed more heavily for website SEs than store SEs | Positive moderator effect (p < .0001) | Supported |

| Positive moderator effect (p < .0001). Replicated in second study (p < .05) | Supported | ||

| H2: Customers who visit the website will weigh the affective dimension (i.e., emotional qualities)—such as inspiration—less heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction than customers who visit the store | Affective distance: The (distal) website evokes high-level construal, which offsets (proximal) concrete emotional qualities for website SEs versus store SEs | Negative moderator effect (p < .0001) | Supported |

| H3: Customers who visit the website will weigh the sensorial dimension of CX—such as (a) attractive environment and (b) product appeal ─ less heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store | Central features of touchpoint: Customers use broader categories for mental representations of (distal) websites versus stores, so they weigh (concrete) sensory qualities less heavily for website SEs versus store SEs | Negative moderator effect (p < .0001). Replicated in second study (p < .001) | Supported |

| Negative moderator effect (p < .0001) | Supported | ||

| H4: Customers who visit the website will weigh ease-of-use more heavily in evaluating their SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store | Congruency of construal level: Customers find it easier to process mental representations at the same construal level, and both website and ease-of-use are abstract mental representations | Positive moderator effect (p < .001). Replicated in second study (p < 0.05) | Supported |

| H5: Customers who visit the website will weigh catalog use less heavily in evaluating their current SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store | Hypothetical distance: Websites and catalogs are less congruent than catalogs and stores with respect to vividness, which reduces hypothetical distance | Negative moderator effect (p < .0001) | Supported |

| H6: Customers who visit the website will weigh a prior interaction with a service representative less heavily in evaluating their current SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visit the store | Social distance: The concrete procedural aspects of social experiences are not thematically consistent with website SEs, so they are weighed less heavily | Negative moderator effect (p > .01) | Not supported |

Cognitive qualities and spatial distance

Supporting H1a, customers who visited the website weighed favorable disconfirmation more heavily than those who visited the store (p < 0.0001). Supporting H1b, customers who visited the website weighed price fairness more heavily than those who visited the store (p < 0.001). Both findings are consistent with the CLT view that the distal website reinforces abstract construals of favorable disconfirmation and price fairness in customers’ overall SE satisfaction. The magnitude of these moderating effects are likely to depend on customers’ perceptions of similarity between the two touchpoints (Morales et al., 2005).

Emotional qualities and affective distance

Emotional qualities were represented by inspiration, which has both favorable valence and a high arousal level (Böttger et al., 2017). Supporting H2, customers weighed inspiration (p < 0.0001) less heavily for website SEs than store SEs. This finding is consistent with the CLT perspective that the (distal) website offsets the concrete construal of inspiration in customers’ overall SE satisfaction because emotional qualities are associated with smaller affective distance such that consumers process its mental representation with low-level construal.

It was also useful to examine the effects of discrete emotions—frustrating, exciting, control, and boring—to determine whether they were the same or different from our affective measure (inspiration). First, as expected, exciting and control had favorable direct effects, while frustrating and boring had unfavorable main effects (see Table 4.) Second, in terms of absolute magnitude, the main effects of emotions are large and customers weighed negative emotions (frustrating, boring) more heavily than positive emotions (exciting, control). Third, the (distal) website negatively moderated both high arousal emotions, frustrating and exciting. Thus, combining the main and interaction effects, the (net) absolute magnitude of frustrating is larger online and the (net) absolute magnitude of exciting is smaller online. Fourth, the website positively moderated both low arousal emotions, control and boring. Thus, combining the main and interaction effects, the (net) absolute magnitude of control is larger online and the (net) absolute magnitude of boredom is smaller online. These findings suggest that the moderating effects of touchpoints on discrete emotions may depend on factors beyond arousal and valence. For example, customers have more freedom to avoid negative emotions and seek positive emotions in the store than on the website. The interactions of touchpoints and discrete emotions warrant additional research.

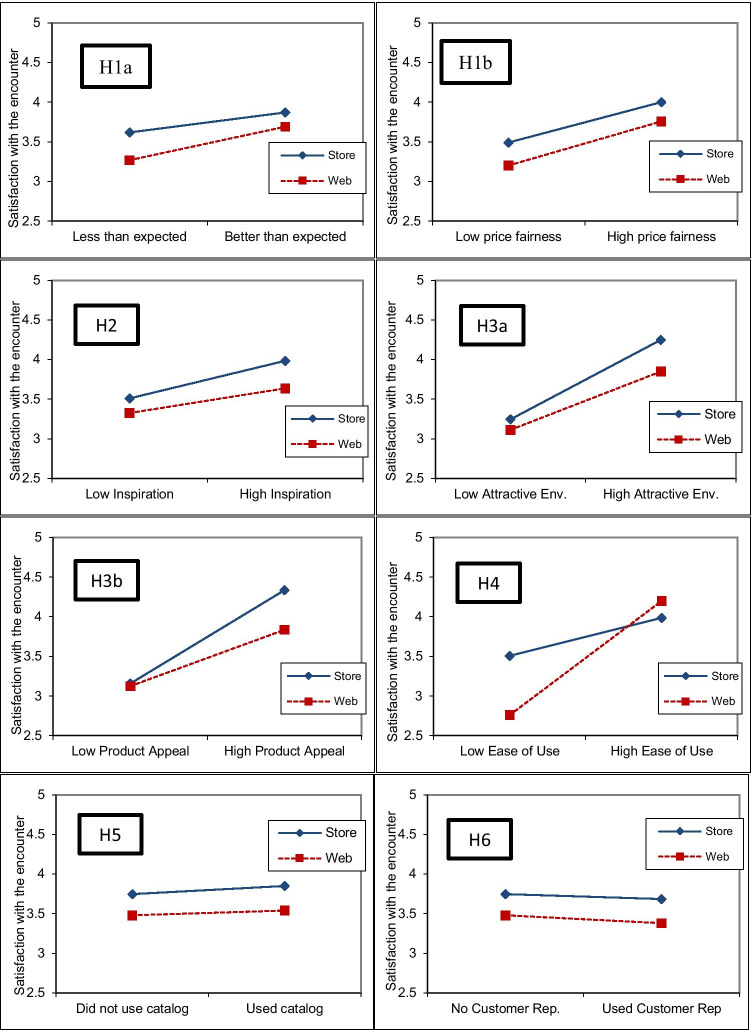

Sensorial qualities and central touchpoint features

As depicted in Fig. 2, the size of the moderating effect of the website on the sensorial (H3a, H3b) dimension of the SE was large. Supporting H3a and H3b, customers who visited the website weighed sensorial qualities—attractive environment and product appeal—less heavily as they evaluated their satisfaction than those who visited the store (p < 0.0001). This result is consistent with CLT, which predicts that (concrete) sensorial qualities, unlike intangibles, are more closely aligned with (proximal) store SEs than with (distal) website SEs. The difference was especially large when the sensorial attribute level was high, implying that there was little “satisfaction payoff” for this retailer from improving sensorial qualities on the website versus the store.

Fig. 2.

Interaction effects

Behavioral qualities

Ease-of-use: Congruency

Supporting H4, customers who visited the website weighed ease-of-use (p < 0.0001) more heavily than those who visited the store. This result is consistent with the CLT perspective that it is easier for customers to process mental representations that are at the same construal level, where both ease-of-use and website are at the same (abstract) construal level. It is also consistent with prior empirical work in which flow and ease-of-use were key drivers of customer satisfaction with online SEs (Weijters et al., 2007). As shown in Fig. 2, the moderating effect of the touchpoint created a crossover effect, whereby high ease-of-use was associated with much higher SE satisfaction for the website versus the store. For this retailer, there was little “satisfaction payoff” from improving ease-of-use for the store versus the website.

Catalog use: hypotheticality

The results support H5, which predicted that customers who visited the website would weigh prior interactions with the catalog less heavily in their evaluation of their SE satisfaction than customers who visited the store (p < 0.0001). This result is consistent with the CLT perspective regarding the congruency of the presentation medium; catalog use was especially powerful in the less rich website environment.

Social qualities: Service representatives and social distance

We did not find support for H6, which predicted that customers who visited the website would weigh prior interactions with service representatives less heavily as they evaluated their current SE satisfaction when compared with customers who visited the store. The coefficient of the interaction term had a negative sign, but it was not statistically significant. One explanation is that the two events were sufficiently different that the customer did not consider them as part of the same customer journey (Lasaleta & Redden, 2018).

Control variables: Individual and market characteristics

Although we did not propose hypotheses, there was a rich set of effects due to market and customer characteristics. Overall satisfaction levels were slightly higher in North America and Asia Pacific relative to Europe, but the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), as indicated by the main effects shown in Table 4. However, the interaction effects show that website satisfaction levels were significantly lower (p < 0.05) in North America and Asia Pacific relative to Europe. The size of the interaction effects more than offset the weak main effects of the regional dummies, which indicates that customers considered the retailer’s website performance to be worse than its overall performance. The retailer is headquartered in Europe, so these results suggest that it has been less successful at designing website SEs in overseas markets.

The model comprised 36 parameters capturing country- and store-specific random effects for our key predictors (favorable disconfirmation, inspiration, attractive, appeal, price fairness, ease-of-use, catalog use, and service representative). These parameters are shown in the columns on the right side of Table 4. They capture idiosyncratic country and store effects, which are different for each variable. For example, the random country effects for attractive environment and product appeal were twice as large as those for price fairness and ease-of-use. The likely reason is that high variability across countries in the random coefficients for attractive and appeal was due to country-specific differences in the customers’ preferences for sensorial attributes, whereas country-specific differences in preferences for cognitive or behavioral attributes were somewhat less differentiated.

The retailer competes in the home décor, furnishings, and related services category. Since its stores are located in urban areas worldwide, variation in customer satisfaction is primarily due to differences in urban living conditions captured by three variables: house studio, house apt, and living single. Satisfaction levels were higher when the customer lived in a studio or apartment with another individual—probably because space was an important consideration for home furnishings. After controlling for these differences, fixed effects of country descriptors such as the size and growth rate of the home furnishings category, disposable income, education, percentage of urban population, and Internet penetration were not statistically significant in our model.

Discussion

The current study contributes to the marketing, service, and retailing literature by describing how touchpoints shape customers’ perceptions and evaluations of their SEs. It extends and tests the TCQ framework (De Keyser et al., 2020) and provides CLT-based theoretically grounded knowledge about satisfaction formation for a SE at a touchpoint. It provides an integrated, in-depth description of how touchpoints moderate eight qualities that reflect the CX dimensions and provides initial evidence on how their importance varies across markets around the world. The findings further build a comprehensive model of how customers weigh experience qualities to evaluate satisfaction with the SE and how the satisfaction formation process differs across touchpoints. As summarized in Table 5, seven of our eight predictions were supported. We found moderating effects of the touchpoint (website versus store) for the following CX dimensions of the SE: cognitive (favorable disconfirmation, price fairness), emotional (inspiration), sensorial (attractive environment and product appeal), and behavioral (ease-of-use, catalog use) dimensions. We found no moderating effect for the social dimension (prior interactions with a service representative).

Standardization versus localization

This paper is based on 2.4 million customer experiences during SEs that occurred through websites and stores in 47 countries; it shows large and systematic differences across touchpoints. It demonstrates the robustness of the main and interaction effects of eight experience qualities for five CX dimensions across countries. In the HLM model, the effects of experience qualities were represented by fixed (stable) effects across countries and stores as well as random (unique) effects. Thus, there was sufficient stability across countries for the standardization of some experience qualities as well as sufficient variation to demonstrate a need for (some) localization or context adaptation. Prior work has detected touchpoint differences for a single experience quality (e.g., for a single website or store in one country). Our findings highlight the importance of customizing each service design quality at different levels (touchpoint, country, and store) to improve the satisfaction of the local clientele. Our study is unique because the HLM model detected fixed and random effects after controlling for individual, market, social, and environmental variables, as well as service brand.

Customers use one touchpoint as their referent

The cooperating retailer began as a traditional “bricks-and-mortar” brand that now has a global reach. It subsequently added websites in each country and (later) delivery services. Our study shows that the store’s holistic image is a powerful, concrete (proximal) referent for all customers. Although this global retailer is highly successful, there is a “dark side” to the strength of its store image as a primary referent. It supports customers’ in-store SEs, but when the SE takes place on the retailer’s (distal) website, the customer weighs cognitive discrepancies relative to prior beliefs based on the store referent (favorable disconfirmation). As shown in Fig. 2, panel 1, when the SE was worse than expected, satisfaction with the in-store SE was much higher than satisfaction with the website SE. These findings extend previous conceptual work on brand experience by showing that the retail brand strategy can shape customers’ responses to SEs (Verhoef et al., 2009). They provide empirical evidence consistent with conceptual work on service strategy (Bharadwaj et al., 1993) and service brand management (Berry, 2000).

Online customers focus on price and ease-of-use for different reasons

Customers who visited the website weighed price fairness more heavily than those who visited a store (see Fig. 2, panel 2). They construed price fairness at a high (abstract) level, which was reinforced by the greater spatial distance of the website versus the store. Firms seek to differentiate their offerings on the basis of branded services to make customers more willing to pay a higher price for their differentiated value proposition. For most firms, the large effects of price fairness for website SEs versus store SEs indicate the importance of creating a strong online value proposition. It can be difficult for firms to differentiate CX on the website such that customers will view price fairness favorably.

Due to touchpoint congruency, customers who visited the retailer’s websites paid more attention to ease-of-use than those who visited its stores. When perceived ease-of-use was low, the impact on satisfaction was much more negative on the website, and when it is high, satisfaction was higher on the website (See Fig. 2, panel 6). This result surprised us (despite theory) because the cooperating firm’s stores were extremely large (average of 300,000 square feet) and had grown consistently; they carried a wide assortment of 10,000 products. Customers found it challenging to navigate the store, find products and information, select items from storage areas, and then check out either using the self-checkout or a cashier. However, the results clearly showed that customers continued to weigh ease-of-use more heavily online.

Stores magnify and websites dampen emotional responses

We studied the emotional quality inspiration, which has a favorable valence and a high arousal level. Customers who visited the cooperating firm’s website weighed inspiration less heavily. This result is consistent with the CLT perspective that the (distal) website offsets customers’ concrete construal of inspiration in customers’ overall SE satisfaction. Interestingly, we found that the website had a mixture of moderating effects on discrete emotions. This finding suggests that it is difficult to create highly favorable and arousing emotional qualities online (versus stores). As technologies improve in terms of convenience and social presence (Grewal et al., 2017), firms will likely be able to reduce the affective distance inherent in website SEs through virtual technologies such that customers respond similarly to how they respond to store SEs. The cooperating retailer takes every opportunity to increase customers’ engagement with its emotional and sensorial qualities through advertising, videos, and catalogs. Our findings suggest that these efforts will more strongly enhance the store SE than website SE.

Sensorial qualities must align with central touchpoint features