Abstract

Introduction

Increasing the diversity of the emergency medicine (EM) workforce is imperative, with more diverse teams showing improved patient care and increased innovation. Holistic review, adapted from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), focuses on screening applicants with a balanced method, valuing their experiences, attributes, and academic metrics equally. A core tenet to holistic review is that diversity is essential to excellence.

Objective

Implementation of holistic review into the residency application screening process is effective at improving exposure to underrepresented in medicine (URiM) applicants.

Methods

After adjustment of our residency application screening rubric, improving our balance across the experience, attributes, and metrics domains, we conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing the representation of URiM applicants invited to interview, interviewed, and ranked by composite score compared to our previous primarily metric‐based process.

Results

A total of 8,343 applicants were included in the study. Following implementation of holistic review, we saw an increase in the absolute percent of URiM applicants invited to interview (+11%, 95% confidence interview [CI] = 6.9% to 15.4%, p < 0.01), interviewed (+7.9%, 95% CI = 3.6% to 12.2%, p < 0.01), and represented in the top 75 through top 200 cutpoints based on composite score rank. The mean composite score for URiM applicants increased significantly compared to non‐URiM applicants (+9.7, 95% CI = 8.2 to 11.2, p < 0.01 vs. +4.7, 95% CI = 3.5 to 5.9, p < 0.01).

Conclusion

Holistic review can be used as a systematic and equitable tool to increase the exposure and recruitment of URiM applicants in EM training programs.

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), in their common program requirements, and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) have called for residencies across specialties to work in conjunction with their institutions to “engage in practices that focus on a mission driven, ongoing, systematic recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents.” The latest numbers from the AAMC show that White doctors make up 56% of the physician workforce and Asian physicians 17%, while only 6% and 5% of physicians are Hispanic and Black, respectively.1 It is projected that by 2042, minority populations in the United States will become the majority, further solidifying the importance of increasing the diversity of the physician workforce, perhaps in a no more important specialty than emergency medicine (EM). There are many reasons why a more diverse physician workforce is important. Physician teams that procure diversity within an institution provide multiple benefits including improved revenue and innovation,2 greater patient satisfaction,3 and better patient outcomes.2 Underrepresented physicians tend to serve patient populations that are congruent with their race/ethnicity at a 20% higher rate compared to non‐underrepresented physicians.4 Mounting evidence shows the importance of increasing racial congruence between physicians and patients in the reduction of health disparities.5 Additionally, diverse physicians are more likely to work in underserved communities,6 and the quality of education within programs is improved with increased diversity.7 Data from the AAMC show that there is a decline in racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine today,8 which weakens our programs, our hospitals, and our specialty.9

The AAMC recommends holistic review as a tool to help programs to systematically and equitably focus recruitment on diversity as well as mission alignment with institution‐specific goals. Holistic review as defined by the AAMC “refers to mission‐aligned admissions or selection processes that take into consideration applicants’ experiences, attributes, and academic metrics as well as the value an applicant would contribute to learning, practice, and teaching. Holistic review allows admissions committees to consider the ‘whole’ applicant, rather than disproportionately focusing on any one factor.”10Holistic review can be further clarified through its core principles, including:

Applicant selection criteria are broad, clearly linked to [program's] mission and goals, and promote numerous aspects of diversity as essential to excellence.

-

Selection criteria include experiences and attributes as well as academic performance. These criteria are:

Used to assess applicants in light of their unique backgrounds and with the intent of creating a richly diverse interview and selection pool and resident body.

Applied equitably across the entire candidate pool.

Modified to reflect the singular purpose of a specific institution and the unique mission that an institution may have.

Supported by student performance data that show that certain experiences or characteristics are linked to that individual's likelihood of success as a physician.

Schools consider each applicant's potential contribution to both the school and the field of medicine, allowing them the flexibility to weigh and balance the range of criteria needed in a class to achieve their institutional mission and goals.

Race and ethnicity may be considered as factors when making admission‐related decisions only when aligned with mission‐related educational interests and goals associated with student diversity, and when considered as a broader mix of factors, which may include personal attributes, experiential factors, demographics, or other considerations10

Holistic review that includes the experience, attributes, and metrics (EAM) model that the AAMC recommends is one tool to meet the goal of widening the lens in which applicants are reviewed. The result of this increased lens is that residency programs will be more likely to increase the diversity within their institution. Additionally, it is a mechanism that can be applied equitably to pursue applicants who align with the program's mission and values. One of the key factors of holistic review is the commitment that diversity is a driver of institutional excellence. If there is conflict on this core concept, programs will not be able to advance to improve diversity within their institution. As stated in the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine Graduate Medical Education Handbook for Holistic Review,11 “Valuing diversity should not be considered giving ‘special consideration’ to a person because they are from a certain group/identity. The diverse and individual perspective, experience, and language that the individual brings as part of their identity should be viewed as a ‘skill’ that is valuable and sought out in the division/department/program.” In this sense, diversity should be considered a skill in its own right.

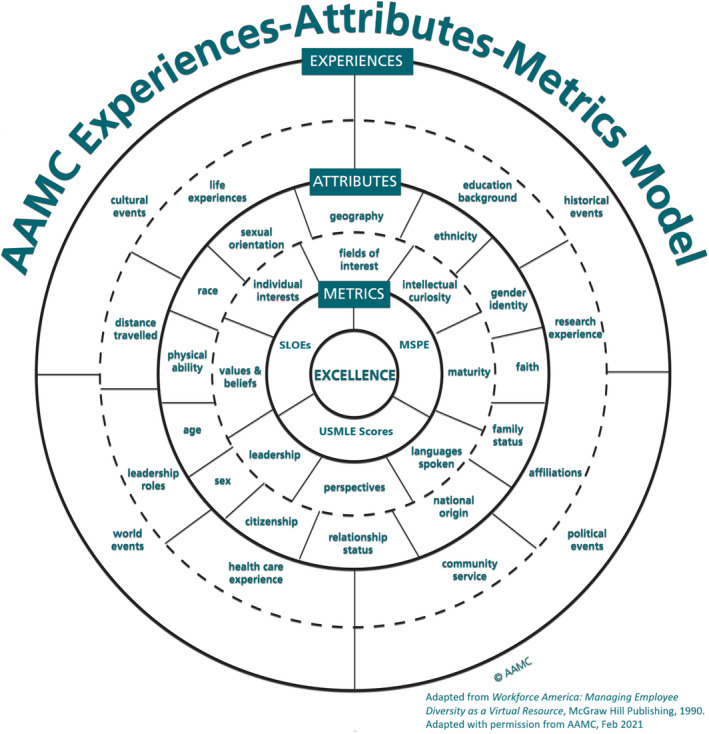

The EAM model seeks to implement the following core principles in the application review process: emphasize the importance of giving individualized consideration to every applicant; provide operational guidance for developing mission‐driven, diversity‐oriented processes; and encourage applying a balanced approach to assess the experiences, attributes, and academic metrics of each candidate.12 The EAM model can perhaps be most succinctly defined graphically (Figure 1), but each component can be further described as such:

Experiences are twofold, comprising both person‐level experiences such as volunteerism, work experience, leadership positions, in addition to population‐level experiences, which includes the societal context in which an applicant has experienced their life, ranging from historical racism to current events.

Attributes include applicants’ personal qualities, comprising not only demographic data including race, ethnicity, gender identity, and socioeconomic status but also personal characteristics including languages spoken, intellectual curiosity, resilience, etc.

Metrics include what are traditionally considered objective measures of academic performance, including medical school, class rank, Alpha Omega Alpha (AOA) membership, United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores, standardized letter of evaluations (SLOE), and clinical rotation grades.

FIGURE 1.

AAMC experience–attributes–metrics (EAM) model. AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; SLOEs, standardized letters of evaluation; USMLE, United States Medical Licensing Examination

By definition, holistic review seeks to provide an evenly balanced assessment of an applicant's experiences, attributes, and metrics, with no single component being disproportionately represented. Such a grading system with a defined scoring system may also help eliminate implicit bias compared to scores that rely more on reviewer gestalt, which have been shown to be affected by implicit bias.13

The residency recruitment process is composed of three main phases: screening, interviewing, and selection. In practice, screening is the process of reviewing applicants’ folders for consideration of an interview, interviewing offers more personal insight into applicants’ character and goals, and selection is the process by which applicants are prioritized for the rank match list. It is important to recognize that efforts to increase diversity must be employed at each step along this continuum. Failure to prioritize diversity at the screening phase cannot be corrected at the selection phase, because diverse applicants will not have had the opportunity to interview and progress through the recruitment process. This study describes the implementation of holistic review into the residency application screening process with the goal of providing a systematic and equitable way to increase the diversity of interviewed and ranked applicants within a single residency program.

METHODS

Implementation of holistic review

Holistic review is not a ready‐made process that can be quickly implemented into residency selection. Rather, it must be customized to each individual program. A central tenet of the AAMC’s Holistic Review Initiative is that it must be built around the mission of the institution or program for which it is being used to recruit.10 As such, the first step in implementing holistic review is not only to clearly define the goal of the recruitment process but also to explicitly state the mission of the training program and institution. This process helps in prioritizing criteria for application screening and ensures alignment between the recruiting process and the overall strategic goals of the institution. The one element of holistic review that should be universal across institutions is the idea that “diversity is essential to institutional excellence.” Diversity, however, should be viewed broadly, including racial and ethnic diversity without either minimizing its role or making it the sole focus of recruitment.

Once consensus is achieved, the next step is balancing the contributions of the screening rubric in accordance with the domains defined by the AAMC—experiences, attributes, and metrics (EAM). The EAM model can be confusing, with overlap of domains across traditional measures of medical student performance. For example, while the medical student performance evaluation is considered a metric, the “noteworthy characteristics” or elements of the narrative introduction may have information relevant to an applicant's experiences and attributes. While reviewers were instructed to cull information for completing the rubric from all parts of the application, for simplicity's sake, we classified each of the grading criteria on our rubric according to a single category of the EAM model.

After each grading element was classified, it was clear that similar to many institutions, our grading scheme was heavily weighted toward traditional metrics, accounting for 80% of our application screening score. To provide a better balance across the three domains of the EAM model, we adjusted weighting for certain scoring criteria, including eliminating the score contribution of USMLE scores. A historic USMLE cutoff was used to screen out applicants, but there was no score differentiation applied to applicants who fell above this cutoff. In addition, underrepresented in medicine (URiM) applicants that fell below the USMLE cutoff had a complete review of their application with the opportunity to be reactivated based on reviewer discretion.

Despite changing score weighting, we still found ourselves short of balance across the EAM domains, particularly in the area of attributes. To better account for applicants’ attributes, we created two new scores for our grading rubric, mission and perspective scores. Both are simple binary scores, and reviewers were instructed to consider the applicant's entire application to determine if a given applicant met the scoring criteria. The mission score assesses an applicant's alignment with our mission, particularly that their application demonstrates a “clear passion and track record of patient‐centered care and altruism, dedication to the underserved, and a commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion.” The perspective score allows an objective weight to be assigned to applicants who “will provide a unique perspective amongst our residency community based on background, including but not limited to: race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, first generation college graduate, underrepresented group in our program, low socioeconomic status, or disadvantaged background.” In addition, we divided scores for letters of recommendation, classifying SLOEs in the metric domain, but classifying other, often narrative, letters of recommendation in the attribute domain, beause these letters frequently speak more to the personal qualities and character of an individual applicant. Other characteristics that most program directors seek within their future residents, such as interpersonal and communication skills, integrity, professionalism, reliability, dependability, motivation, initiative, teamwork, and professionalism, were also added to attributes.14

Regarding experiences, we combined the experience (outside activities) and publication (research score) fields in Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) into one score that accounted for both significant experiences (leadership positions, advanced degrees, etc.) and experiences that demonstrate certain characteristics (resilience, innovation, team‐mindedness, etc.). Again, this is an area of our rubric where there is overlap between the AAMC experience and attributes domains, but these scores were ultimately classified under experiences. In completing the experience score, reviewers were instructed to keep a running count from a prespecified list of both significant experiences and important characteristics represented by experiences for a given applicant. The experience score was then calculated based on the total number of points tallied. This provided a more objective and defensible calculation of this score that traditionally has been very subjective within our own program.

Overall, while we made significant improvement in balancing our scoring rubric across the EAM model, we still fell short of perfect balance, with total weight for each domain of 22%, 36%, and 42% for experiences, attributes, and metrics, respectively. A comparison of the change in our screening rubric is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of grading rubric prior to and following implementation of holistic review

| % of application score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2020 | 2021 | Delta | |

| Experiences | 17.8% | 22.1% | 4.3% |

| Outside activity | 8.9% | 0.0% | –8.9% |

| Research | 8.9% | 0.0% | –8.9% |

| Experiences (including research) | — | 22.1% | 22.1% |

| Attributes | 2.2% | 36.0% | 33.8% |

| Personal statement | 2.2% | 2.9% | 0.7% |

| Non‐eSLOE letter(s) of recommendation | — | 11.0% | 11.0% |

| Mission | — | 11.0% | 11.0% |

| Perspective | — | 11.0% | 11.0% |

| Metrics | 80.0% | 41.9% | –38.1% |

| USMLE score(s) | 22.2% | 0.0% | –22.2% |

| Medical school | 2.2% | 2.2% | 0.0% |

| Medical student performance evaluation | 27.8% | 17.6% | –10.1% |

| Letter(s) of recommendation (including SLOEs) | 27.8% | 0.0% | –27.8% |

| eSLOE | — | 22.1% | 22.1% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

Abbreviations: eSLOE, electronic standardized letter of evaluation; SLOE, standardized letter of evaluation; USMLE, United States Medical Licensing Examination.

To standardize grading as best as possible, all application reviewers met as a group with residency leadership prior to the opening of the ERAS to be instructed on how to use the new grading rubric, discuss questions and clarifications, and compare grades across a group of three sample applications to gain consistency in scoring. This training was in addition to our annual request that reviewers complete several implicit association tests (IAT)15 and attend a virtual equity training program to try to better understand and mitigate their own biases in the screening process. Additionally, application reviewers were blinded to applicant pictures in ERAS, which have been shown to contribute to bias.16 Finally, we adjusted our interview questions to eliminate what had previously been an assessment of “fit” in exchange for evaluation of alignment with our mission.

Effect of holistic review on applicant screening

To assess the effect of implementation of holistic review on our residency application screening process, we performed a retrospective cohort study, evaluating data from the ERAS archives from 2016 to 2020, as well as application data for the current year, 2021, following completion of all interviews. All students who applied to our program across these 6 years were included in our data analysis. Data elements collected for each applicant included applicant gender, self‐identification (race/ethnicity), date of interview offer, interview score, and total composite score after interviews. URiM applicants were defined as any applicant with one or more of the following terms included in their self‐identification: Black or African American, Hispanic Latino or of Spanish Origin, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The numbers of URiM applicants who applied, were invited to interview, were interviewed, and fell within certain rank cutpoints based on overall composite score were identified for each year. It is important to note that the rank cutpoints are based on composite score rank only and do not necessarily reflect position on the rank list submitted to the National Residency Matching Program (NRMP). Averages were calculated for the 5 years preceding implementation of holistic review (2016–2020) and were compared to data from the 2021 match cycle in which holistic review was used for application screening.

All data were extracted from ERAS, imported to an online relational database (Airtable) for data processing and organization, and subsequently transferred into SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute) for analysis. Descriptive statistics for continuous data are reported as means and categorical data are reported as percentages. Bivariate statistical methods (e.g., Fisher's exact test and independent‐samples t‐tests) were performed to test for differences between the preintervention and postintervention groups. Estimates of percentage and mean change with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05 based on two‐tailed testing. This study was reviewed and approved under an education‐based blanket exemption through the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

A total of 8343 applicants were included in the study. In the preimplementation phase (2016–2020), an average of 1,347 total students applied per year, of whom 202 (15%) were URiM, 394 (29%) of the total applicant pool were invited to interview, and 287 (21%) interviewed. In the postimplementation of holistic review phase (2021), 1,608 total students applied, of whom 296 (18%) were URiM, 456 (28% of all applicants) were invited to interview, and 411 (26%) interviewed. The proportion of URiM applicants who applied to our program increased by 3.4% (95% CI = 1.3% to 5.5%, p < 0.01) comparing the preimplementation average to applications from the 2021 match cycle. Following implementation of holistic review, there was a significant absolute increase in URiM applicants invited to interview (+11%, 95% CI = 6.9% to 15.4%, p < 0.01), interviewed (+7.9%, 95% CI = 3.6% to 12.2%, p < 0.01), and represented in the top 75 through top 200 cutpoints based on composite score rank (Table 2). There was a trend toward increased URiM applicants in the top 25 and top 50 cutpoints as well, although it did not reach significance. The mean composite score for all applicants increased following implementation of holistic review (+5.5, 95% CI = 4.2 to 6.7, p < 0.01), but the increase was significantly larger for URiM applicants (+9.7, 95% CI = 8.2 to 11.2, p < 0.01) compared to non‐URiM applicants (+4.7, 95% CI = 3.5 to 5.9, p < 0.01).

TABLE 2.

Effect of holistic review on recruitment of URiM applicants pre/post

| Pre | Post | Comparison | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Average | SD | 2021 | Delta (95% CI) | p‐value | |

| Total applied | 1,297 | 1,362 | 1,356 | 1,290 | 1,430 | 1,347 | 50.88 | 1608 | — | — |

| URiM applied | 180 (13.9) | 196 (14.4) | 198 (14.6) | 200 (15.5) | 236 (16.5) | 202 (15.0) | 18.42 (0.9) | 296 (18.4) | +3.4% (1.3% to 5.5%) | <0.01 |

| Total interview invites | 431 | 409 | 400 | 359 | 371 | 394 | 26.02 | 456 (100.0) | — | — |

| URiM interview invites | 63 (14.6) | 48 (11.7) | 54 (13.5) | 61 (17.0) | 43 (11.6) | 53.8 (13.7) | 7.57 (2.0) | 113 (24.8) | +11.1% (6.9% to 15.4%) | <0.01 |

| Total interviewed | 317 | 297 | 295 | 257 | 270 | 287.2 | 21.23 | 411 | ||

| URiM interviewed | 55 (17.4) | 36 (12.1) | 36 (12.2) | 42 (16.3) | 25 (9.3) | 38.8 (13.5) | 9.79 (3.0) | 88 (21.4) | +7.9% (3.6% to 12.2%) | <0.01 |

| URiM Top 25 | 1 (4.0) | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (12.0) | 1 (4.0) | 2.0 (8.0) | 0.89 (3.6) | 5 (20.0) | +12.0% (–4.4% to 28.4%) | 0.07 |

| URiM Top 50 | 5 (10.0) | 6 (12.0) | 4 (8.0) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) | 4.4 (8.8) | 1.02 (2.0) | 6 (12.0) | +3.2% (–6.5% to 12.9%) | 0.48 |

| URiM Top 75 | 9 (12.0) | 11 (14.7) | 5 (6.7) | 7 (9.3) | 4 (5.3) | 7.2 (9.6) | 2.56 (3.4) | 16 (21.3) | +11.7% (1.9%–21.5%) | <0.01 |

| URiM Top 100 | 13 (13.0) | 14 (14.0) | 8 (8.0) | 13 (13.0) | 7 (7.0) | 11.0 (11.0) | 2.90 (2.9) | 25 (25.0) | +14.0% (5.0%–22.9%) | <0.01 |

| URiM Top 125 | 15 (12.0) | 15 (12.0) | 12 (9.6) | 15 (12.0) | 8 (6.4) | 13.0 (10.4) | 2.76 (2.2) | 30 (24.0) | +13.6% (5.7%–21.5%) | <0.01 |

| URiM Top 150 | 20 (13.3) | 18 (12.0) | 16 (10.7) | 19 (12.7) | 12 (8.0) | 17.0 (11.3) | 2.83 (1.9) | 34 (22.7) | +11.4% (4.3%–18.4%) | <0.01 |

| URiM Top 175 | 22 (12.6) | 18 (10.3) | 19 (10.9) | 25 (14.3) | 16 (9.1) | 20.0 (11.4) | 3.16 (1.8) | 39 (22.3) | +10.9% (4.3%–17.4%) | <0.01 |

| URiM Top 200 | 29 (14.5) | 21 (10.5) | 23 (11.5) | 34 (17.0) | 17 (8.5) | 24.8 (12.4) | 6.01 (3.0) | 49 (24.5) | +12.1% (5.8%–18.4%) | <0.01 |

| Interviewed composite score all | 67.6 | 69.4 | 69.7 | 73.5 | 74.3 | 70.7 (±11.7) | 76.2 (±10.1) | 5.5 (4.2–6.7) | <0.01 | |

| Non‐URiM interviewed composite score | 68.9 | 69.6 | 70.0 | 74.0 | 74.5 | 71.3 (±11.1) | 76.0 (±10.5) | 4.7 (3.5–5.9) | <0.01 | |

| URiM interviewed composite score | 61.6 | 68.2 | 67.8 | 70.9 | 72.2 | 67.4 (±14.5) | 77.1 (±8.6) | 9.7 (8.2–11.2) | <0.01 | |

Data are reported as n (%) or mean (±SD).

Abbreviation: URiM, underrepresented in medicine.

DISCUSSION

The call to increase the racial and ethnic diversity in EM is not a new one. In 2008, the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD) provided recommendations to EM programs to “broaden the selection criteria” and not just include traditional metrics, “but also meaningful intangibles such as leadership, community service, and other relevant life experiences.”17 In 2016, Boatright et al,18 found that fewer than half of the 72% of EM residency programs that responded to a survey had instituted at least two of the multiple recruitment recommendations outlined by the CORD committee in 2008. While we as a community of educators have been talking about increasing diversity for over a decade, it seems that ample opportunities still exist to make meaningful change in our recruitment efforts. To do this work, programs need both the motivation for change and a commitment to the benefits of a diverse workforce, but also the tools to prioritize diversity in a fair manner. We recommend holistic review as just this, an effective and equitable system to screen applicants with a goal of improving diversity.

And yet, being true to the foundations of holistic review as outlined by the AAMC is critical. Anecdotally, it seems that many programs purport the use of holistic review in their residency screening process, with national talks on holistic review occurring annually at EM academic meetings. In fact, prior to the redesign of our own screening process, we were confident that we were considering applicants holistically based on the fact that we reviewed and scored each component of an applicant's ERAS file and evaluated them overall, considering “the whole person.” Despite weighing each component of an individual's applications, our scoring rubric still heavily favored metrics, representing 80% of the total screening score.

Over reliance on metrics for residency screening disproportionately eliminates URiM applicants, where data shows that systemic bias undervalues URiM students in terms of USMLE scores, medical school rank, clinical grades, and AOA status.19, 20 Favoring these criteria only propagates these proven biases and pushes URiM applicants down or out of each stage of the recruitment process, but most notably the screening process. In addition to bias, metrics also have been shown to have poor correlation to success within residency. For example, the USMLE score, cited as an important factor to EM program directors in consideration of resident selection,21, 22 has shown poor correlation to success in residency.23, 24, 25 USMLE scores have, however, been shown to positively correlate to higher first‐pass success rate on the ABEM initial certifying examination (ICE). Regarding first‐pass success on the ICE, in 2017 Harmouche et al.26 demonstrated that the minimum USMLE score to predict 95% first‐pass success was 227. Based on these data, one could argue for a minimum USMLE score of around 227, with no additional weight assigned to higher USMLE scores given poor correlation to residency success and limited additional yield in terms of ICE first‐pass success. Despite movement of the USMLE Step 1 to pass/fail in 2022, we suspect that both the biases and the improper use of test scores as a screening tool will simply shift to the USMLE Step 2 scores.

While this study only reports the effect of our intervention on the representation of URiM applicants as defined by race and ethnicity, we believe that this intervention also increased the diversity of our applicants based on other factors including gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or other unique perspectives traditionally underrepresented in medicine. Given that ERAS only allows self‐identification by race and ethnicity, but not these other defining attributes, we are unable to prove any increase in diversity as it pertains to these other underrepresented populations.

In 2019, Garrick et al.27 showed success in increasing URiM applicants matched into an EM residency program with a multimodal approach. This group used a screening process that included a holistic component, but 75% of their screening score would still be classified as metric‐based according to the AAMC EAM model. However, this work underscores the critical action of including a commitment to recruiting a diverse workforce at every step of the recruitment continuum, including screening, interviewing, and selection. While prioritization of URiM applicants at rank is critical to success, failure to effectively screen URiM applicants with an equitable and systematic tool means that institutions fail to capitalize on the opportunity to even consider these applicants for selection. In discussing Garrick et al., it is critical to note that after their interventions, they showed a significant increase in the diversity of their residency classes, with no negative effect to academic performance as indicated by on‐time graduation, ABEM ICE and oral examination first‐pass success, and academic appointments following graduation.

A discussion of our process would not be complete without mentioning barriers to successfully implementing holistic review within our program. Systemic bias exists in every institution and reliance on traditional metrics‐based measures of success are deeply rooted within the culture of medicine. In our own experience, getting early buy‐in from departmental and institutional leaders; clearly and prospectively documenting our recruitment goals; providing explicit instruction, reference, and training for our application reviewers; and unapologetically challenging biases as they presented were critical actions to the success of our intervention. In addition, our recruitment committee completed bias training and multiple IAT, although additional data support public disclosure and discussion of these results may be more effective in addressing biases.28

LIMITATIONS

This study has a number of limitations. First, it is a single‐site study and therefore may be limited in generalizability. While application reviewers underwent bias training and education on how to utilize the new grading rubric, it is likely that reviewer biases still had some effect on individual applicant scores. However, there would be nothing to suggest that this bias would be any different from previous years.

While the AAMC’s EAM model is simple enough to comprehend, application of this model can get somewhat more muddled in terms of categorizing scores to one of the domains: experience, attributes, and metrics. This is particularly true with experience and attributes, where some overlap may occur. For example, an applicant's experience as a class president in their medical school should be valued as an experience but also speaks to attributes of leadership for that applicant. We attempted to assign our grading rubric to the EAM model as best as we could, but recognize that some overlap across domains exists.

One of the main outcomes of this study was the comparison of composite score rank of URiM applicants before and after implementation of holistic review. While the intervention described was only explicitly applied to application screening, the composite score includes the applicants’ interview score. We recognize that this may confound the conclusions about the effect of holistic review on the representation of URiM applicants at different composite rank cutpoints; however, the themes identified in implementing holistic review and viewing each applicant as a whole person likely bled into the interview process and may have affected interview scores, although this effect is not accounted for in this data. Additionally, the composite score rank is not the applicants rank position as submitted to the NRMP but shows where applicants fell by rank prior to discussions and prioritization of the NRMP rank list.

Finally, as mentioned in the discussion, not all applicants had the opportunity to clearly identify all of the experiences and attributes that we sought. This is largely due to the limitations of the ERAS application, not allowing applicants the opportunity to identify themselves in areas that programs may seek for holistic review such as gender identity, first‐generation medical school or college, sexual orientation, parental income level, rural‐raised, or medicine as a second career. With programs’ goals of increasing diversity across many of these demographics, future changes to the ERAS application may be necessary to offer equitable self‐identification of these important characteristics.

CONCLUSIONS

In an effort to increase the number of underrepresented physicians in emergency medicine, an all‐ encompassing, holistic view around the recruitment process must occur. Residency placement remains one barrier to the number of underrepresented in medicine emergency medicine physicians entering the workforce. Holistic review offers a systematic and equitable approach to screening residency applicants to increase the exposure and recruitment of diverse applicants in emergency medicine training programs. Increasing diversity in emergency medicine is not about fulfilling quotas, but building stronger, more effective, learning environments and health care teams.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

Sungar WG, Angerhofer C, McCormick T, et al. Implementation of holistic review into emergency medicine residency application screening to improve recruitment of underrepresented in medicine applicants. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(Suppl. 1):S10–S18. 10.1002/aet2.10662

Supervising editor: Teresa Y. Smith MD, MSEd

REFERENCES

- 1.Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges. c2021. Accessed February 26, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data‐reports/workforce/interactive‐data/figure‐18‐percentage‐all‐active‐physicians‐race/ethnicity‐2018

- 2.Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(4):383‐392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laveist TA, Nuru‐Jeter A. Is doctor‐patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296‐306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1305‐1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient‐physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997‐1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver KB Jr, Nadamuni MV, Ahn C, Nivet M, Cryer B, Okorodudu DO. Mentoring black men in medicine. Acad Med. 2020;95(12S):S77‐S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clayborne EP, Martin DR, Goett RR, Chandrasekaran EB, McGreevy J. Diversity pipelines: the rationale to recruit and support minority physicians. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(1):e12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landry AM, Stevens J, Kelly SP, Sanchez LD, Fisher J. Under‐represented minorities in emergency medicine. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(1):100‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holistic Review. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/services/member‐capacity‐building/holistic‐review

- 11.UCSF GME Handbook for Holistic Review and Best Practices for Enhancing Diversity in Residency and Fellowship Programs. University of California at San Francisco. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://bit.ly/3sH4hKF

- 12.Holistic Principles in Resident Selection: An Introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed February 26, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020‐08/aa‐member‐capacity‐building‐holistic‐review‐transcript‐activities‐GME‐081420.pdf

- 13.Kassam AF, Cortez AR, Winer LK, et al. Swipe right for surgical residency: exploring the unconscious bias in resident selection. Surgery. 2020;168(4):724‐729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Results of the 2016 Program Directors Survey. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2016. Accessed February 27, 2021. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/180/

- 15.Preliminary Information. Project Implicit. c2011. Accessed February 28, 2021. https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html

- 16.Corcimaru A, Morrell MC, Morrell DS. Do looks matter? The role of the Electronic Residency Application Service photograph in dermatology residency selection. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(4):13030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heron SL, Lovell EO, Wang E, Bowman SH. Promoting diversity in emergency medicine: summary recommendations from the 2008 Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD) academic assembly diversity workgroup. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(5):450‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boatright D, Tunson J, Caruso E, et al. The impact of the 2008 Council of Emergency Residency Directors (CORD) panel on emergency medicine resident diversity. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(5):576‐583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(5):487‐496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, Moore E, Nunez‐Smith M. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the alpha omega alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):659‐665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crane JT, Ferraro CM. Selection criteria for emergency medicine residency applicants. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):54‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Negaard M, Assimacopoulos E, Harland K, Van Heukelom J. Emergency medicine residency selection criteria: an update and comparison. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2(2):146‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Wayne DB. Are United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 1 and 2 scores valid measures for postgraduate medical residency selection decisions? Acad Med. 2011;86(1):48‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang A, Gilani C, Saadat S, Murphy L, Toohey S, Boysen‐Osborn M. Which applicant factors predict success in emergency medicine training programs? A scoping review. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(3):191‐201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner JG, Schneberk T, Zobrist M, et al. What predicts performance? A multicenter study examining the association between resident performance, rank list position, and United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 scores. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(3):332‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harmouche E, Goyal N, Pinawin A, Nagarwala J, Bhat R. USMLE scores predict success in abem initial certification: a multicenter study. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(3):544‐549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrick JF, Perez B, Anaebere TC, Craine P, Lyons C, Lee T. The diversity snowball effect: the quest to increase diversity in emergency medicine: a case study of Highland's emergency medicine residency program. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(6):639‐647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capers Q 4th, Clinchot D, McDougle L, Greenwald AG. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):365‐369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]