Abstract

Cats were experimentally infected with a Florida isolate of Haemobartonella felis in order to collect organisms and evaluate the immune response to H. felis. Cryopreserved organisms were thawed and injected intravenously into nonsplenectomized and splenectomized cats. Splenectomized animals were given 10 mg of methylprednisolone per ml at the time of inoculation. Blood films were evaluated daily for 1 week prior to infection and for up to 60 days postinfection (p.i.). Blood for H. felis purification was repeatedly collected from splenectomized animals at periods of peak parasitemias. Organisms were purified from infected blood by differential centrifugation, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblot analysis. Serum was collected from nonsplenectomized animals prior to and for up to 60 days p.i. and was used on immunoblots to identify antigens. The combination of splenectomy and corticosteroid treatment resulted in marked, cyclic parasitemias without concurrent severe anemia, providing an opportunity to harvest organisms in a manner that was not lethal to the animals. Several antigens (150, 52, 47, 45, and 14 kDa) were identified. An antigen with a molecular mass of approximately 14 kDa appeared to be one of the most immunodominant and was consistently recognized by immune sera collected at various times during the course of infection. These data suggest that one or more of these antigens might be useful for the serologic diagnosis of H. felis infections in cats.

Haemobartonella felis is an epicellular, hemoparasite of domestic cats that causes a clinical disease known as feline infectious anemia or hemobartonellosis. Haemobartonella spp. are currently classified in the family Anaplasmataceae, order Rickettsiales. However, Haemobartonella spp., including H. felis, have recently been shown by 16S rRNA gene sequencing to be more closely related to Mycoplasma spp. (23). H. felis has a worldwide distribution and is believed to be one of the most common causes of hemolytic anemia in domestic cats (8, 10). Even so, many questions regarding the transmission, prevalence, and clinical impact of this organism on the domestic feline population remain unanswered, largely because a reliable and readily accessible means of diagnosis is not available.

H. felis may produce clinical disease alone or concomitantly with other agents such as feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) (6, 8, 22). The lack of a reliable means of diagnosis of H. felis infection makes accurate assessment of concurrent infections difficult. However, in one survey, as many as 35% of H. felis-infected cats were FeLV positive, with even higher percentages of positivity seen among cats presenting with severe clinical disease (8).

Uncomplicated infection with H. felis occurs in four phases: the (i) preparasitic, (ii) acute, (iii) recovery, and (iv) carrier phases (10). The prepatent period for experimentally infected cats is 2 to 3 weeks. Clinical signs may develop shortly after this time, but this is quite variable; some experimentally infected animals did not develop clinical signs until 4 to 6 weeks postinfection (p.i.). Common clinical abnormalities include anemia, depression, weight loss, icterus, pyrexia (in about 50% of infected cats), and splenomegaly. Clinical disease is most often associated with the acute phase, but organisms can be identified only periodically during this time and rarely, if at all, in chronically infected carriers (10, 11). Reported mortality rates indicate about 33% of the infected animals die, mostly during the acute phase (6, 10, 20). With appropriate antibiotic therapy most animals survive uncomplicated H. felis infection, but many remain subclinical carriers, probably for life (3, 4, 10, 11). However, because a reliable means of diagnosis is not readily available, infection with H. felis often remains undetected and many animals go untreated.

Presently, the clinical diagnosis of H. felis infection relies on the positive identification of organisms in peripheral blood smears with Romanowsky-type or acridine orange stains (5). Even in acute stages of the disease, however, a definitive identification of H. felis infection is difficult because of rapidly fluctuating parasite numbers and a lack of a consistent correlation between parasitemia and clinical signs (10).

Recently, a species-specific PCR assay based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence of H. felis was developed (19). This assay may provide workers with a valuable tool with which they can answer many questions regarding the transmission and prevalence of the disease. Reports indicate that the assay detects acutely ill and relapsing animals but does not consistently detect asymptomatic carrier cats (3, 4). However, PCR-based assays are labor-intensive, requiring specialized equipment and highly trained personnel. In addition, these assays are limited to research and reference laboratories. A sensitive and specific serological assay based on one or more H. felis antigens would provide a more accessible means of diagnosis for clinicians presented with cats with suspected hemobartonellosis in which organisms are not identified in the peripheral blood.

Currently, the Haemobartonella spp. are not amenable to in vitro cultivation. Therefore, in this study, we used differential centrifugation to purify a Florida (FL) isolate of H. felis from the peripheral blood of experimentally infected cats. Purified organisms were then used with immune sera from experimentally infected animals in Western immunoblot assays to identify the immunodominant antigens of H. felis and to characterize the humoral responses of cats to H. felis infection. This was done to determine the feasibility of a serology-based assay for the diagnosis of H. felis infection and to identify H. felis antigens which might be targeted for future production as recombinant test antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

A total of six female, domestic short-haired cats bred for research were purchased from a licensed dealer. These cats were certified to be free of FeLV and FIV infection by testing for these viruses prior to and 45 days following inoculation with H. felis-infected blood. At preinfection, negative control serum was collected from each cat. Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood films were examined daily for 7 days prior to inoculation with H. felis to ensure that no hemoparasites were present. Two of the four animals to be infected were splenectomized 21 days prior to inoculation. The splenectomized cats were each given 10 mg of a single intramuscular injection of methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrol; The Upjohn Company, Kalamazoo, Mich.) per kg of body weight at the time of inoculation. Two of the four animals to be infected were not splenectomized. The splenectomized animals were used primarily for the harvesting of organisms and nonsplenectomized cats were used primarily for the production of immune sera. Two uninfected cats were used as blood donors for the infected animals.

Organisms and immune sera.

An FL isolate of H. felis (10) which had been cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen was intravenously inoculated into two splenectomized cats and two nonsplenectomized cats. All cats were examined daily, and peripheral blood was drawn each morning for the monitoring of the packed cell volume (PCV), total protein, icterus index, and parasite numbers. Infectivity was quantified with Wright-Giemsa-stained blood films and was recorded as a percent parasitemia. Infected blood was collected from splenectomized cats during peak parasitemias (when 80 to 90% of the erythrocytes were infected) in amounts that did not result in mortality (usually 40 ml). An equal volume of uninfected blood from a donor cat was transfused back to the infected animal. Immune serum was collected from all infected animals at intervals of 15, 30, 45, and 60 days p.i.

Antigen preparation.

H. felis-infected whole blood was collected in heparin and centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The plasma and buffy coat were removed, and packed cells were washed and centrifuged three times in an equal volume of 0.15 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2). The wash solution and any remaining buffy coat cells were removed after each centrifugation. Wright-Giemsa-stained blood films of washed erythrocytes were examined for the presence of parasites. The pelleted erythrocytes were then placed in an equal volume of 0.15 M PBS (pH 7.2)–0.15% (vol/vol) polyoxyethylene-sorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20)–1.5% (wt/vol) disodium EDTA and were incubated on a rocker at room temperature for 2 h to dislodge the H. felis organisms from the erythrocytic membranes. The preparation was centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was removed. Wright-Giemsa-stained blood films were examined to ensure that the parasites were dislodged. The supernatant containing H. felis organisms was centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the pelleted organisms were resuspended in 5.0 ml of 0.15 M PBS (pH 7.2). The preparation was further purified from any host cell components by differential centrifugation through 20% diatrozoate meglumine and diatrozoate sodium (RenoCal-76; Bracco Diagnostics Inc., Princeton, N.J.) at 22,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of 0.15 M PBS (pH 7.2) and stored at −20°C. Most H. felis preparations resulted in 0.5 ml of antigen at a concentration of approximately 1.0 to 2.0 mg/ml, as determined by the Coomassie blue G dye-binding assay (21). Erythrocytic antigens, prepared from experimental animals prior to infection with H. felis, were used as a negative control. Briefly, 1 ml of uninfected whole blood was washed and centrifuged three times in an equal volume of 0.15 M PBS (pH 7.2), with the wash solution and any remaining buffy coat removed after each centrifugation. The washed erythrocyte pellet was suspended in 5 ml of 0.15 M PBS (pH 7.2), freeze-thawed five times in liquid nitrogen, and used as an uninfected erythrocytic antigen preparation.

Electron microscopy.

A portion of the purified H. felis preparation was prepared in McDowell and Trumps fixative for transmission electron microscopy. The sample was washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide, washed several times with distilled water, and dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and then in 100% acetone. The sample was polymerized in 100% EMbed 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, Pa.) and then trimmed and ultrasectioned on a Leica Ultracut R ultramicrotome (Leica Microscopy and Scientific Instruments, Deerfield, Ill.). The sections were stained in 2% uranyl acetate and then Reynold’s lead citrate.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

The protein concentrations of the microorganism and noninfected erythrocyte preparations were determined by the Coomassie blue G dye-binding assay as described previously (21). The proteins were dissolved in one-half their volume of a 3× sample buffer containing 0.1 M Tris (pH 6.8), 5% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 50% glycerol, 7.5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.00125% bromophenol blue and were heat denatured at 100°C for 3 min. Solubilized microorganisms or noninfected erythrocytes were applied onto 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide-SDS gels at 20 μg per lane and the gels were electrophoresed. The gels were fixed in 25 mM Tris–191.8 mM glycine–20% methanol and were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; Amersham International plc, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England).

Immunoblots with antisera.

Nitrocellulose membranes containing transferred proteins were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) milk in PBS with 0.25% Tween 20 and washed with 1% (wt/vol) milk in PBS with 0.25% Tween 20 as described previously (1). The membranes were probed with antisera collected from infected animals at 14, 21, 30, 45, and 60 days p.i. Serum dilutions of 1/300 or greater were used. As a negative control, preinfection serum was used with erythrocytic and H. felis antigens at concentrations equal to or greater than that used for infected sera. In addition, immune serum was used with erythrocytic antigens to confirm that the antigens identified in the H. felis preparations were not of erythrocyte origin. The membranes were washed as described previously (1) and were probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-cat immunoglobulin G (whole molecule; ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Biochemical Division, Aurora, Ohio) at a dilution of 1/20,000. The membranes were processed for enhanced chemiluminescence with detection reagents containing luminol (SuperSignal Substrate; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) as a substrate and were exposed to X-ray film (Hyperfilm-MP; Amersham International plc) to visualize the bound antibody.

RESULTS

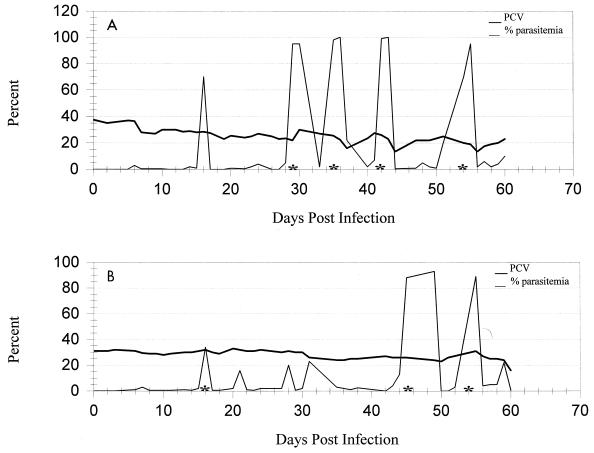

Splenectomy and the administration of methylprednisolone facilitated the development of recurrent episodes of marked parasitemias. Parasitemias approaching 100% were seen in both splenectomized cats, usually without a significant drop in PCV (Fig. 1). This allowed repeated harvesting of large numbers of organisms without the development of severe clinical disease. Replacement of harvested, infected blood by transfusions with uninfected whole blood maintained a relatively stable PCV. High parasitemias sometimes persisted for 2 or more days in splenectomized animals; however, in some instances the number of infected erythrocytes went from 90 to <1% within a 3-h period. Indirect Coombs’ tests for antierythrocytic antibodies were negative for both cats.

FIG. 1.

PCV and percent parasitemia for each of two splenectomized cats (A and B) from 0 to 60 days postinoculation with an FL isolate of H. felis. Asterisks indicate periods when the organisms were harvested from the peripheral blood.

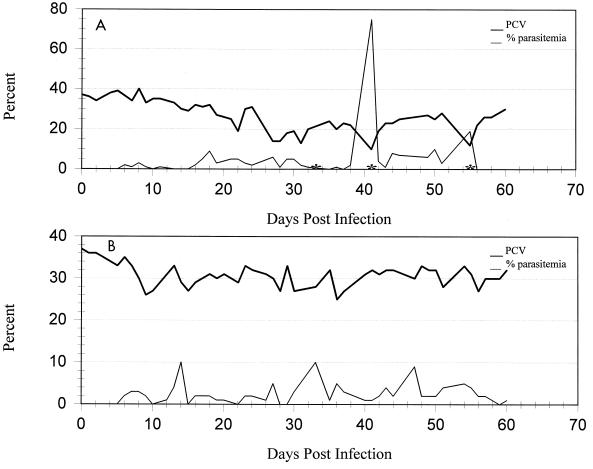

Neither nonsplenectomized cat developed recurrent, high-level parasitemias suitable for the harvesting of organisms. One animal became clinically ill by day 18 p.i., when parasite numbers reached 9% parasitemia. The PCV decreased from 32 to 19% by day 22 p.i. (Fig. 2A). The cat was Coombs’ test positive when the test was performed at 37°C with a 1:4 dilution. The severity of the disease necessitated a whole-blood transfusion and the administration (2 days) of doxycycline (orally at 10 mg/kg twice daily). The animal’s condition was stable for approximately 2 weeks, but parasite numbers then increased dramatically and the PCV decreased precipitously to 10%. The severity of the disease necessitated a second transfusion and eventual prolonged treatment with doxycycline at the same dosage for 21 days. The other nonsplenectomized cat developed an infectivity which peaked at a 10% parasitemia (Fig. 2B). Clinical signs were minimal, consisting of a mild anemia that persisted following the appearance of parasites in the peripheral blood at day 14 p.i. This cat did not become Coombs’ test positive.

FIG. 2.

PCV and percent parasitemia for each of two spleen-intact cats (A and B) from 0 to 60 days postinoculation with an FL isolate of H. felis. Asterisks indicate periods when doxycycline administration was necessary to prevent mortality.

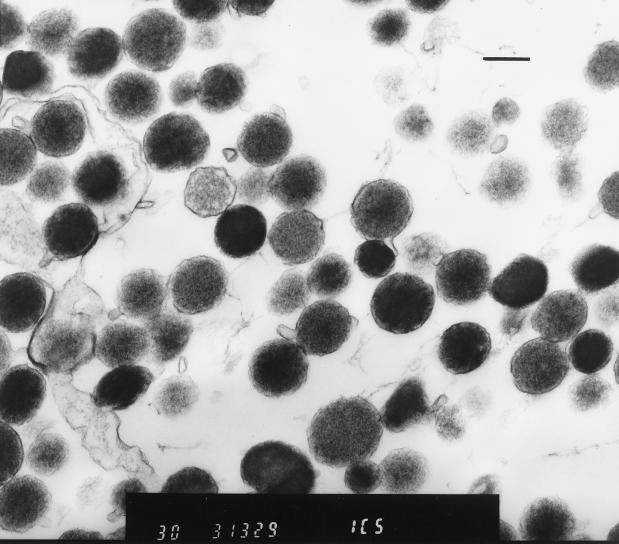

Collection of infected erythrocytes in tubes containing heparin as an anticoagulant prevented dislodging of the parasites from the erythrocyte membranes, which may occur when EDTA is used as an anticoagulant (10). Pelleted erythrocytes maintained original levels of parasitemia after gentle washes in PBS. This was evaluated with Wright-Giemsa-stained smears prepared from erythrocytes following each wash in PBS (data not shown). However, blood films prepared after incubation of infected erythrocytes in 1.5% EDTA for 2 h at room temperature revealed that the vast majority of the organisms were dislodged from the cell membranes. Slow-speed centrifugation allowed easy separation of uninfected erythrocytes (pellet) from H. felis organisms (supernatant). A solution of 1.5% EDTA resulted in mild to moderate hemolysis of erythrocytes; however, lower concentrations (1.0% EDTA for 2 h) left significant numbers of organisms remaining on the erythrocyte membranes (data not shown). Host cell membranes remaining in the H. felis-rich supernatant after slow-speed centrifugation were subsequently removed by differential centrifugation with 20% diatrozoate meglumine and diatrozoate sodium. This resulted in an H. felis preparation suitable for evaluation for antigen. The purity of the preparation was evaluated by electron microscopy (Fig. 3), revealing minimal host cell membrane contamination.

FIG. 3.

Electron micrograph of H. felis bodies purified from infected whole blood by differential centrifugation. Bar, 1 μm.

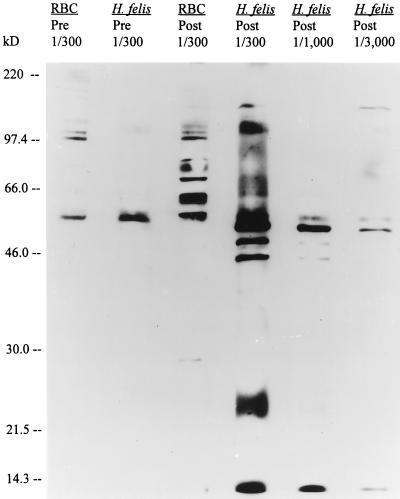

Western immunoblot analysis of purified H. felis organisms was done to detect individual antigens. Uninfected erythrocytic preparations were used as negative controls to ensure that the identified antigens were of parasite origin. Serial dilutions of immune sera collected at 21 days p.i. identified five major antigens with molecular masses of 14, 45, 47, 52 and 150 kDa (Fig. 4). Three of these (14, 52, and 150 kDa) appeared to be the most immunodominant antigens. We have designated them major antigen 1 (MA1) (14 kDa), major antigen 2 (MA2) (52 kDa), and major antigen 3 (MA3) (150 kDa). A 56-kDa antigen was also recognized by immune sera at various dilutions. An antigen of similar size, however, was identified in uninfected erythrocyte preparations and when H. felis preparations were used with preinfection sera (Fig. 4). This antigen was assumed to be of erythrocytic origin.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot of an FL isolate of H. felis and noninfected, feline erythrocytes (RBC) with preinfection serum (Pre) or immune serum (Post) collected from an experimentally infected animal 21 days postinoculation. The fractions (1/300 to 1/3,000) indicate the dilutions of serum used. Molecular size standards (in kilodaltons) are given on the left.

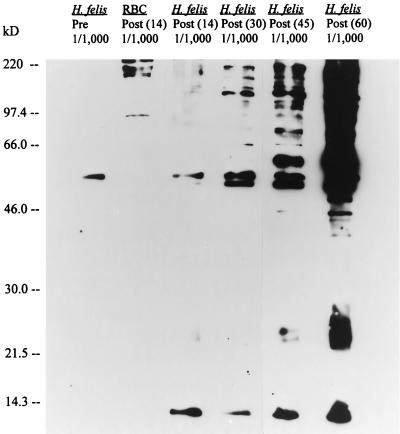

In order to evaluate the temporal immune response of infected cats to H. felis, purified organisms or uninfected erythrocytes were used with either preinfection sera or sera collected at 14, 30, 45, or 60 days p.i. Antibodies to some H. felis antigens were detected with immune sera collected as early as 14 days p.i. (Fig. 5). Bands of 14-kDa and possibly 52-kDa antigens were recognized by immune sera at dilutions of 1/1,000. Several antigens were recognized by sera collected at 30, 45, and 60 days p.i., and the antibody response to H. felis antigens intensified during the course of the infection (Fig. 5). These data suggest the 14-kDa antigen of H. felis is not only one of the most immunodominant antigens but is also consistently recognized by immune sera at various times during the course of infection.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot of an FL isolate of H. felis and noninfected, feline erythrocytes (RBC) with preinfection serum (Pre) or immune serum collected from an experimentally infected animal at 14 days (Post 14), 21 days (Post 30), 45 days (Post 45), and 60 days (Post 60) postinoculation. The fraction (1/1,000) indicates the dilution of serum used. Molecular size standards (in kilodaltons) are given on the left.

DISCUSSION

Parasite numbers have been known to fluctuate rapidly in the peripheral blood of cats infected with H. felis, resulting in a poor correlation between the clinical signs and parasite numbers in the peripheral blood (10). There is substantial evidence implicating the spleen as the major organ involved in the removal of the organisms from infected erythrocytes (17, 18). H. felis organisms were removed less readily in splenectomized cats, resulting in parasitemias that lasted approximately twice as long as those in nonsplenectomized cats (16). Splenectomy performed on recovered, carrier cats resulted in the transient reappearance of parasites, in most cases without the development of clinically significant anemia (11). The administration of methylprednisolone has also been shown to increase circulating parasite numbers in chronically infected carriers (11). For these reasons, animals used for propagation of organisms were splenectomized and administered methylprednisolone prior to inoculation. This resulted in consistently high parasitemias without the concurrent development of severe anemia. PCVs remained stable in infected animals when collected blood was replaced with an equal volume of uninfected blood from donor cats. Parasitemias of 80% or more sometimes persisted for up to 3 days, allowing ample time for collection. However, as reported previously (10), parasite numbers often declined rapidly from >90 to <1% in 3 h or less, even though the animals were splenectomized. Thus, parasite numbers need to be monitored closely to determine the optimal time for harvesting. The mechanism of parasite removal in splenectomized animals is speculative, but macrophages in the lung, liver, and bone marrow are thought to play a significant role (12).

A 1.5% (wt/vol) concentration of disodium EDTA in PBS was effective in releasing the majority of the parasites from infected erythrocytes. This concentration of EDTA has been previously shown to cause the release of a closely related hemoparasite, Eperythrozoon suis, from infected swine erythrocytes (9). However, the infectivity of the purified E. suis organisms was markedly reduced when the organisms were inoculated into susceptible pigs. The investigators concluded that this method of dislodging E. suis from infected erythrocytes produced a nonviable preparation but that the technique was suitable for the preparation of antigens for use in immunological assays. Although we did not attempt infectivity trials with purified H. felis organisms, on the basis of the reported findings with E. suis, we suspect that the viabilities of the purified organisms would be reduced.

Incubation of H. felis-infected erythrocytes for 2 h in a solution containing 1.0% EDTA resulted in significant numbers of organisms remaining attached to erythrocytes. A previous study (9) found that lower concentrations of EDTA (0.75%) were not as effective in releasing E. suis organisms from infected erythrocytes. However, unlike E. suis-infected erythrocytes, a 1.5% concentration of EDTA resulted in a mild to moderate lysis of H. felis-infected erythrocytes. Although it is possible that feline erythrocytes are inherently more sensitive than swine erythrocytes to the effects of EDTA, we speculate that attachment of H. felis to the erythrocytic membranes results in increased erythrocyte fragility, more so than with the attachment of E. suis organisms. Previous studies have demonstrated the production of erosions and pockmarks on erythrocyte membranes in areas where H. felis organisms were attached (13, 24). These lesions were considered to be important in the development of the hemolytic anemia associated with H. felis infection (13).

A method of differential centrifugation with 20% diatrozoate meglumine and diatrozoate sodium was necessary to further separate organisms from the erythrocytic membranes lysed during incubation in EDTA. This method has been shown to be effective in separating rickettsia from host cells in cell culture preparations (7). The concentrations of diatrozoate meglumine and diatrozoate sodium were reduced to enhance recovery of the mycoplasma-like H. felis organisms. The resulting preparation was shown by electron microscopy to contain large numbers of H. felis bodies with minimal erythrocytic membrane contamination.

H. felis antigens of various molecular sizes ranging from 150 to 14 kDa were identified in Western blots. The immune response to some antigens was recognized as early as 14 days p.i. and persisted throughout the course of this study (60 days p.i.). Cats infected with H. felis and mice infected with Haemobartonella muris have been shown by indirect fluorescent-antibody testing to mount an immune response to surface antigens on the organism (10, 23). However, the onset, duration, and specific targets of the immune response have not been previously identified. The detection of H. felis antibodies from 14 to 60 days p.i. indicates that it is possible to diagnose natural infections both during the acute phase of the disease (when clinical hemobartonellosis is most often seen) and during the recovery and carrier phases.

We identified antigens of 150, 52, 47, 45, and 14 kDa in an FL strain of H. felis. One of these antigens, the 14-kDa antigen (MA1), appears to be one of the more immunodominant antigens and is consistently recognized by immune sera during all phases of infection. Previous analysis of antigens of H. muris found antigens of 118, 65, 53, 45, and 40 kDa (23). That study, which used 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, found H. muris to be most closely related to the FL strain of H. felis (89% sequence similarity) (23). The 52- and 45-kDa antigens of H. felis are similar in size to the 53- and 45-kDa antigens of H. muris; however, the antigenic relationships are unknown. Given the close phylogenetic and sequence similarities in the 16S rRNA gene, antigenic cross-reactivity between these two species would seem likely.

There are obvious antigenic differences between these two species, and one of the most immunodominant H. felis antigens (the 14-kDa antigen) was not recognized in H. muris preparations (23). In fact, on the basis of the findings of Rikihisa et al. (23), differences between isolates of H. felis are likely. When the rRNA gene sequences of three strains of H. felis were compared, it was found that an Ohio isolate of H. felis shared an identical gene sequence with an FL isolate; however, a California isolate of H. felis shared <85% sequence similarity (23). Less sequence similarity was identified between these two strains of H. felis than was identified between the FL strain of H. felis and H. muris (23). On the basis of these findings, the investigators concluded that more than one species of Haemobartonella may infect cats. It is possible, therefore, that the five antigens identified in the FL isolate of H. felis may not be conserved in other strains of H. felis.

Although speculative, there is some concern that antigenic variation may play a role in the development of the cyclic parasitemias identified in our experimentally infected animals and those reported previously (10). Antigenic variation has been a proposed mechanism for the development of cyclic parasitemias with other hemoparasites such as Anaplasma marginale (2, 14). This would have a significant impact on the selection of a diagnostic antigen since the use of a conserved antigen would be more beneficial in a serologic test.

We have successfully developed methods for propagation, harvesting, and purification of H. felis organisms from experimentally infected cats. In addition, we have identified five major antigens from an FL isolate of H. felis. We have also shown that the immune response to experimental H. felis infection begins as early as 14 days p.i. and continues throughout the course of the infection. This suggests that it is possible to develop a serologic assay based on one or more of these antigens for the detection of H. felis-infected cats. However, the sensitivity and specificity of particular antigens in detecting infected animals remain unknown. Further work must be done to determine which antigens are conserved and recognized by cats experimentally infected with H. felis isolates from different geographic areas and which antigens are recognized by immune serum from animals infected with closely related organisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Heather Sorenson for technical support in performing Western immunoblot experiments and Karen Vaughn and the Electron Microscopy Core, ICBR, University of Florida, for electron microscopic technical support.

This work was supported by the Division of Sponsored Research grant 2805773-12 from the University of Florida.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alleman A R, Barbet A F. Evaluation of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 3 (MSP3) as a diagnostic test antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:270–276. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.270-276.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alleman A R, Palmer G H, McGuire T C, McElwain T F, Perryman L E, Barbet A F. Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 3 is encoded by a polymorphic, multigene family. Infect Immun. 1997;65:156–163. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.156-163.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berent L M, Messick J B, Cooper S K. Use of a PCR test to detect a fragment of the 16S rRNA of Haemobartonella felis in the blood of acutely parasitemic, asymptomatic, and steroid-challenged carrier cats. Vet Pathol. 1997;34:515. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berent L M, Messick J B, Cooper S K. Detection of Haemobartonella felis in cats with experimentally induced acute and chronic infections, using a polymerase chain reaction assay. Am J Vet Res. 1998;59:1215–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobade P A, Nash A S. A comparative study of the efficiency of acridine orange and some Romanowsky staining procedures in the demonstration of Haemobartonella felis in feline blood. Vet Parasitol. 1987;26:169–172. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(87)90087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobade P A, Nash A S, Rogerson P. Feline haemobartonellosis: clinical, haematological and pathological studies in natural infections and the relationship to infection with feline leukaemia virus. Vet Rec. 1988;122:32–36. doi: 10.1136/vr.122.2.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S M, Popov V L, Feng H M, Walker D H. Analysis of ultrastructural localization of Ehrlichia chaffeensis proteins with monoclonal antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:405–412. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grindem C B, Corbett W T, Tomkins M T. Risk factors of Haemobartonella felis infection in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;196:96–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall S M, Cipriano J A, Schoneweis D A, Smith J E, Fenwick B W. Isolation of infective and non-infective Eperythrozoon suis bodies from the whole blood of infected swine. Vet Rec. 1988;123:651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey J W, Gaskin J M. Experimental feline haemobartonellosis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1977;13:28–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey J W, Gaskin J M. Feline haemobartonellosis: attempts to induce relapses of clinical disease in chronically infected cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1978;14:453–456. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey J W. Haemobartonellosis. In: Greene C E, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1990. pp. 434–442. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain N C, Keeton K S. Scanning electron microscopic features of Haemobartonella felis. Am J Vet Res. 1973;34:697–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieser S T, Eriks I S, Palmer G H. Cyclic rickettsemia during persistent Anaplasma marginale infection of cattle. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1117–1119. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1117-1119.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maede Y, Hata R. Studies on feline haemobartonellosis. II. The mechanism of anemia produced by infection with Haemobartonella felis. Jpn J Vet Sci. 1978;37:49–54. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.37.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maede Y. Studies on feline haemobartonellosis. V. Role of the spleen in cats infected with Haemobartonella felis. Jpn J Vet Sci. 1978;40:141–146. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.40.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maede Y, Murata H. Ultrastructural observation on the removal of Haemobartonella felis from erythrocytes in the spleen of a cat. Jpn J Vet Sci. 1978;40:203–205. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.40.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maede Y. Sequestration and phagocytosis of Haemobartonella felis in the spleen. Am J Vet Res. 1979;40:691–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messick J B, Berent L M, Cooper S K. Development of a PCR-based assay for the detection of Haemobartonella felis in cats and differentiation of H. felis from related bacteria by restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:462–466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.462-466.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nash A S, Bobade P A. Haemobartonellosis. In: Wolderhiwet Z, Ristic M, editors. Rickettsial and chlamydial diseases of domestic animals. Tarrytown, N.Y: Pergamon Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Read S M, Northcote D H. Minimization of variation in the response to different proteins of the Coomassie blue G dye-binding assay for protein. Anal Biochem. 1981;116:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reubel G H, Dean G A, George J W, Barlough J E, Pederson N C. Effects of incidental infections and immune activation on disease progression in experimentally feline immunodeficiency virus-infected cats. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1003–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikihisa Y, Kawahare M, Wen B, Kociba G, Fuerst P, Kawamori F, Suto C, Shibata S, Futohashi M. Western immunoblot analysis of Haemobartonella muris and comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequences of H. muris, H. felis, and Eperythrozoon suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:823–829. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.823-829.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson C F, Gaskin J M, Harvey J W. Ultrastructure of erythrocytes parasitized by Haemobartonella felis. J Parasitol. 1978;64:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]