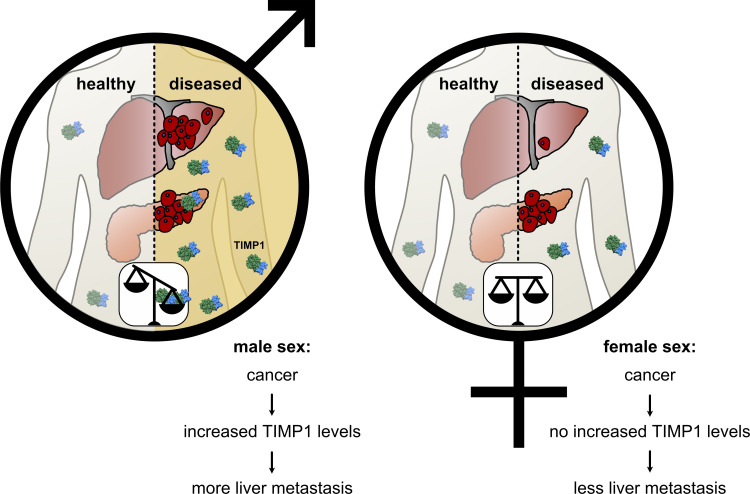

Hermann et al. reveal a lifestyle-independent sex disparity in liver metastasis and survival of pancreatic cancer caused by TIMP1. Increased TIMP1 expression in males predicts liver metastasis in various cancer entities. Such insight into the basis of sex differences substantiates the necessity of considering sex in cancer medicine.

Abstract

Sex disparity in cancer is so far inadequately considered, and components of its basis are rather unknown. We reveal that male versus female pancreatic cancer (PC) patients and mice show shortened survival, more frequent liver metastasis, and elevated hepatic metastasis-promoting gene expression. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP1) was the secreted factor with the strongest male-biased expression in patient-derived pancreatic tumors. Male-specific up-regulation of systemic TIMP1 was demonstrated in PC mouse models and patients. Using TIMP1-competent and TIMP1-deficient PC mouse models, we established a causal role of TIMP1 in determining shortened survival and increased liver metastasis in males. Observing TIMP1 expression as a risk parameter in males led to identification of a subpopulation exhibiting increased TIMP1 levels (T1HI males) in both primary tumors and blood. T1HI males showed increased risk for liver metastasis development not only in PC but also in colorectal cancer and melanoma. This study reveals a lifestyle-independent sex disparity in liver metastasis and may open new avenues toward precision medicine.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

For the majority of all cancer types, it has become increasingly evident that prognosis is remarkably worse for male than for female patients (Clocchiatti et al., 2016; Radkiewicz et al., 2017; Haupt et al., 2021). However, basic components of these sex disparities in cancer have remained poorly understood (Haupt et al., 2021). The notion resulting from large epidemiological studies (Micheli et al., 2009; Radkiewicz et al., 2017) that sex disparities in cancer survival are not only dependent on lifestyle-associated cancer risk factors (Clocchiatti et al., 2016) implies the regulation of distinct steps of cancer progression by sex-biased intrinsic factors (Haupt et al., 2021). Therefore, it is essential to identify intrinsic factors, which regulate sex-dependent cancer progression, and to translate this knowledge to use in the clinic (Wagner et al., 2019). In fact, more adequate consideration of a sex disparity in cancer medicine may open new opportunities in personalized medicine by optimizing diagnosis as well as targeted therapy and thereby substantially improving outcomes for cancer patients (Wagner et al., 2019; Haupt et al., 2021).

Metastasis formation represents the most fatal manifestation of cancer progression and accounts for the vast majority of cancer-associated deaths (Steeg, 2016). Across cancer types, the liver represents the most afflicted target organ of metastasis (Budczies et al., 2015). In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs), the highly lethal and by far the most common subtype of pancreatic cancer (PC; Quaresma et al., 2015; Bray et al., 2018), liver metastasis is exceptionally frequent (Ryan et al., 2014) and lethal (Oweira et al., 2017). An emerging concept explaining efficient liver metastasis is the formation of a metastasis-promoting niche (Peinado et al., 2017), where cancer-related (Seubert et al., 2015) or possibly even cancer-preceding inflammatory processes (Grünwald et al., 2016) condition the liver. On the molecular level, such metastasis-supporting preconditioning is initiated by tumor-derived secreted factors (TDSFs; Krüger, 2015; Peinado et al., 2017), which reach distant organs via the bloodstream, impair homeostasis in distant entities in an organ-specific manner, and thereby determine metastatic organotropism (Hoshino et al., 2015). Experimental overexpression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP1) was shown, for example, to induce metastasis formation preferably in the liver (Seubert et al., 2015). In fact, metastasis-promoting conditioning of the liver is characterized by up-regulation of fibrosis-related (Grünwald et al., 2016; Nielsen et al., 2016; Lenk et al., 2017), immune-related (Nielsen et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019), and lipid metabolism–related (Li et al., 2020) processes and was shown to enable efficient colonization even by nonmalignant tumor cells (Rhim et al., 2012; Seubert et al., 2015). Although these studies show important aspects contributing to the efficacy of liver metastasis, a sex dependency was totally neglected.

In fact, although there is growing evidence for sex disparity in cancer development and therapy (Haupt et al., 2021), data concerning sex-dependent metastasis formation are still missing. Given the clinical observations of sex disparity in cancer survival (Clocchiatti et al., 2016; Radkiewicz et al., 2017) and the fact that metastasis is a major determinant of cancer survival (Steeg, 2016), this study aimed to address sex differences in survival as well as the metastatic spread of one of the most lethal (Quaresma et al., 2015) and most efficiently metastasizing (Ryan et al., 2014) cancer entities, namely PC.

Results

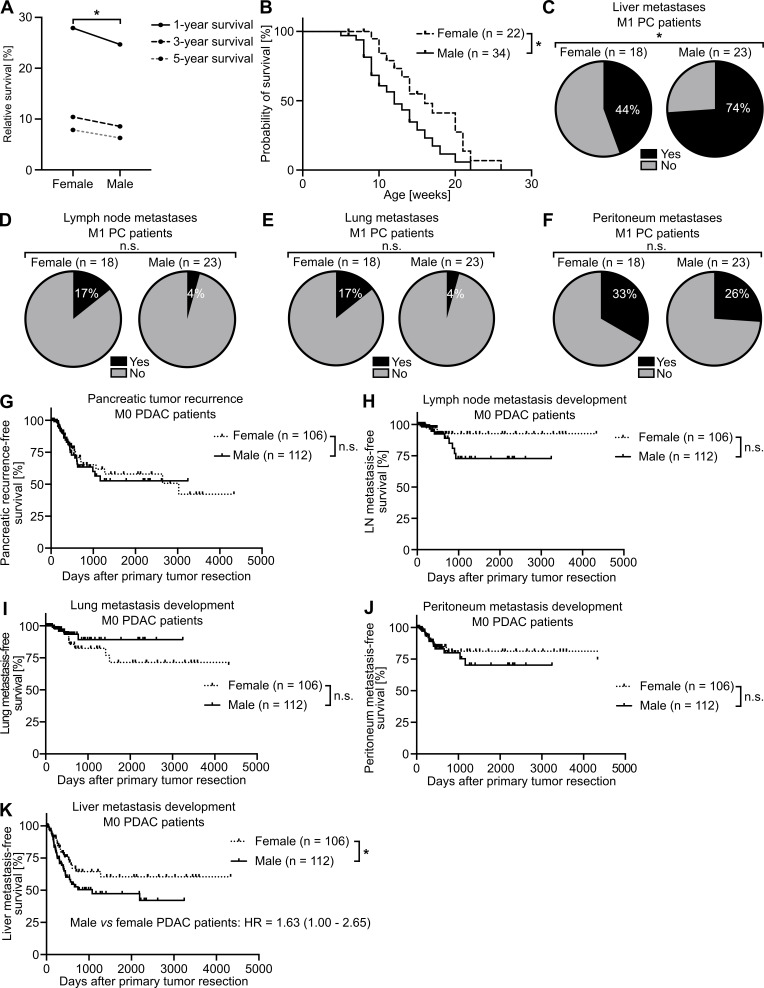

Male patients with PC show decreased survival and more prevalent liver metastasis

The existence of a sex disparity in PC survival became evident from analysis of data derived from the European Cancer Information System (ECIS) database with 101,357 female and 101,227 male PC patients, where relative (i.e., sex-, age-, and region-standardized) survival was shorter in male than in female patients (Fig. 1 A). To further exclude the lifestyle dependency of this finding, we turned to the well-established transgenic Pdx-1+/Cre;Kras+/LSL-G12D;Trp53+/LSL-R172H (KPC) mouse model for PDAC (Hingorani et al., 2005) and confirmed sex disparities in PDAC survival (Fig. 1 B). Because metastasis is the major determinant of survival in cancer (Steeg, 2016), we next analyzed whether PC patients show sex differences in metastasis formation. Evaluation of the metastatic organotropism of patients already diagnosed with metastatic PC (Fig. S1 A) indeed revealed that males showed an increased frequency of metastases specifically in the liver (Fig. 1 C), but not in the LNs (Fig. 1 D), lungs (Fig. 1 E), or peritoneum (Fig. 1 F), as compared with females. Also, in PDAC patients diagnosed without synchronous metastases (M0; Fig. S1 B) from three independent cohorts, where similar disease recurrence was observed between sexes (Fig. S1 C), female and male PDAC patients showed comparable local pancreatic recurrence (Fig. 1 G) as well as development of metastases in LNs (Fig. 1 H), lungs (Fig. 1 I), or peritoneum (Fig. 1 J), whereas we again observed sex differences with respect to metastasis development specifically in the liver (Fig. 1 K). Taken together, these data demonstrate the presence of sex disparities in PC, namely a male-biased shortening of survival associated with a liver-specific increase of metastases.

Figure 1.

PC-afflicted males show decreased survival and increased metastasis specifically in the liver. (A) Relative 1-, 3-, and 5-yr survival rates of female (n = 101,357) and male (n = 101,227) PC patients. Data were derived from the ECIS database. A paired samples t test was employed for statistics. (B) Survival of female (n = 22) and male (n = 34) PDAC-bearing KPC mice. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. (C–F) The proportion of female (n = 18) and male (n = 23) patients with metastatic PC (M1, UICC stage IV) with (yes) or without (no) metastases in the liver (C), LN (D), lung (E), or peritoneum (F). The χ2 test was employed for statistics. (G–K) Disease recurrence in the pancreas (G), LN (H), lung (I), peritoneum (J), or liver (K) of female (n = 106) or male (n = 112) PDAC patients diagnosed without synchronous metastases (M0) and treated with primary tumor resection. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. *, P ≤ 0.05 (A–K).

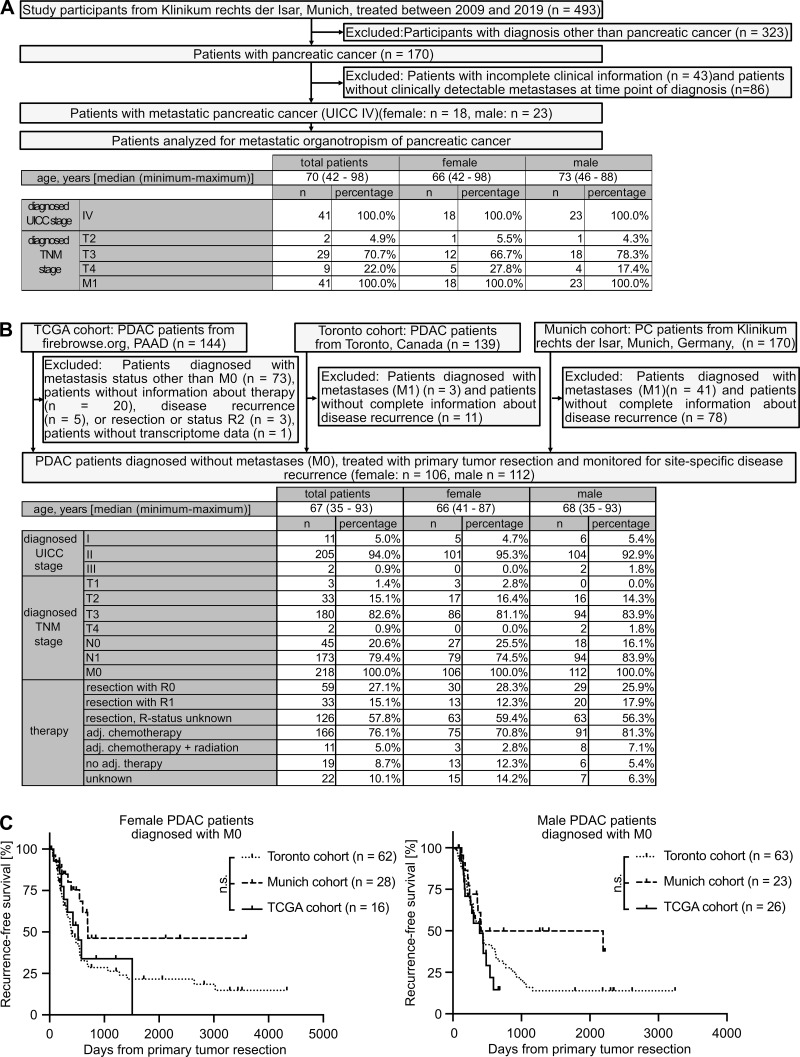

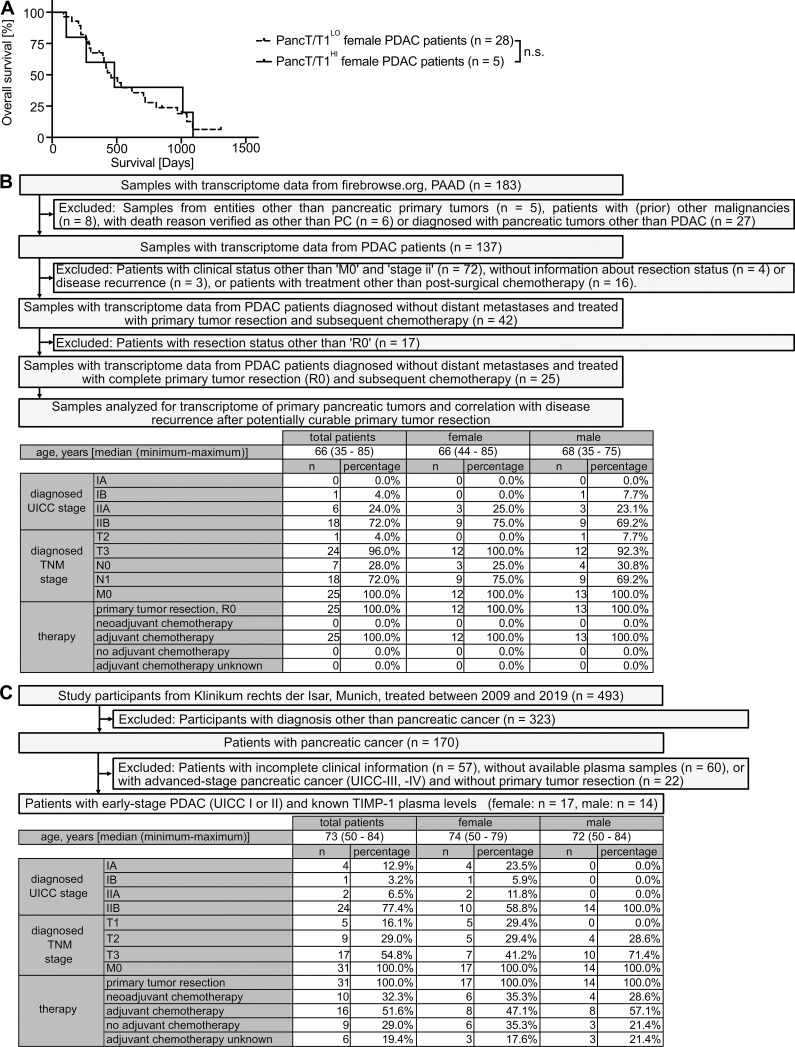

Figure S1.

Inclusion and exclusion of PC patients from different cohorts to analyze site-specific metastasis development. (A) Of 493 total participants, 41 patients with metastatic PC (M1) were included for analysis of the sex-dependent metastatic organotropism of PC. (B) Of 453 patients with PC, 218 patients with comparable disease stage and therapy were included for analysis of sex-dependent, site-specific disease recurrence after primary tumor resection. adj., adjuvant; TNM, tumor, node, metastasis. (C) Female (n = 106; left) and male (n = 112; right) PDAC patients from three independent cohorts (Toronto, Munich, and TCGA cohorts) show similar disease recurrence after primary tumor resection. Log-rank statistics were employed for statistics.

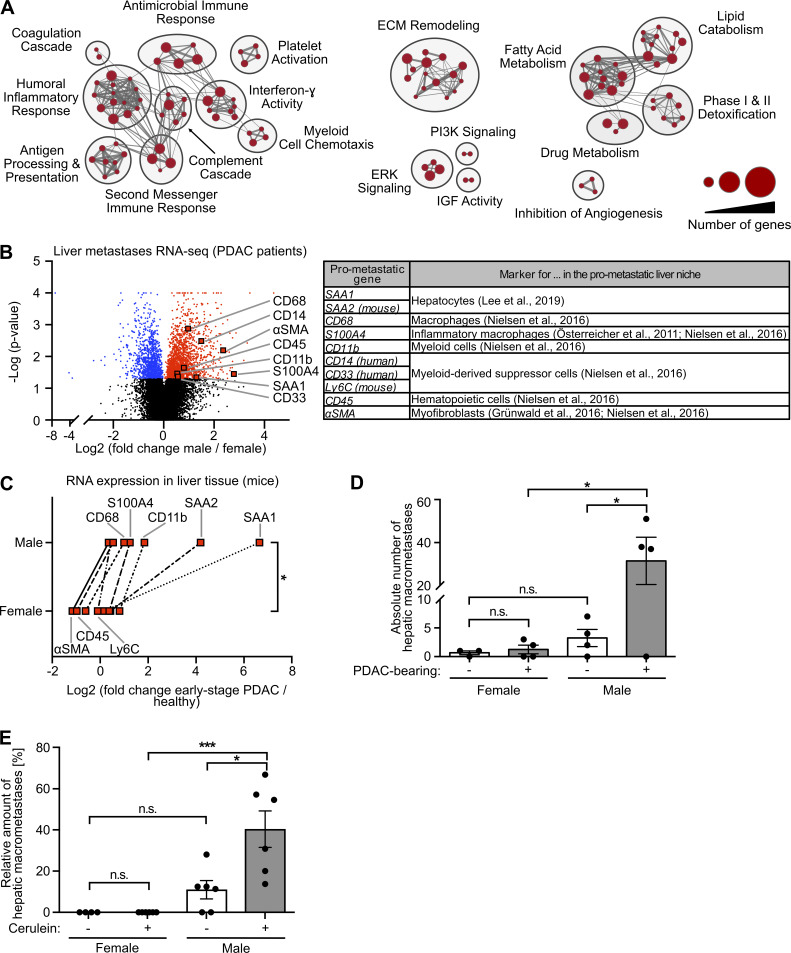

A metastasis-promoting gene expression signature in the liver occurs in a male-biased manner

Because the metastatic organotropism of cancer is driven by organ-specific metastasis-promoting niches (Hoshino et al., 2015), we next addressed whether male-biased liver metastasis was associated with sex-specific differences in the liver tissue of PDAC patients. Evaluation of previously published transcriptomic data (Moffitt et al., 2015; Fig. S2 A) revealed 2,836 genes with sex-dependent expression in PDAC patient–derived metastasis-bearing liver tissue (Table S1). Using these sex-dependently expressed genes in gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that fibrosis-related (e.g., remodeling of extracellular matrix), immune-related (e.g., inflammatory response, myeloid cell chemotaxis), and lipid metabolism–related processes (Fig. 2 A), all of which had been described as characteristics of a metastasis-supporting liver niche (Grünwald et al., 2016; Nielsen et al., 2016; Lenk et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019), were specifically up-regulated in male as compared with female liver tissue (Fig. 2 A). We furthermore identified a distinct mRNA signature up-regulated in the liver of male PDAC patients encoding for distinct metastasis-promoting genes (Fig. 2 B), including the hepatocyte-derived factor serum amyloid A (SAA; Lee et al., 2019) as well as markers for macrophages (Österreicher et al., 2011; Nielsen et al., 2016), myofibroblasts (Grünwald et al., 2016; Lenk et al., 2017), and hematopoietic cells (Nielsen et al., 2016; Fig. 2 B). mRNA expression analysis of liver tissue from PDAC-afflicted KPC mice indeed confirmed male-specific up-regulation of this pro-metastatic gene expression signature in PDAC (Fig. 2 C), whereas, except for CD68, these metastasis-promoting genes were not differentially expressed in liver tissue of healthy female versus male control mice (Fig. S2 B). In fact, increase of the susceptibility of pancreatic disease–primed livers to metastatic colonization was observed only in male and not in female mice, as demonstrated by using two different mouse models that remodel different stages of PC, namely PDAC-afflicted KPC mice (Fig. 2 D) and a mouse model with defined early inflammatory pancreatic lesions (Fig. 2 E). Together, these results demonstrate that increased liver metastasis in males with PDAC is associated with a male-biased metastasis-promoting conditioning of the liver in PDAC.

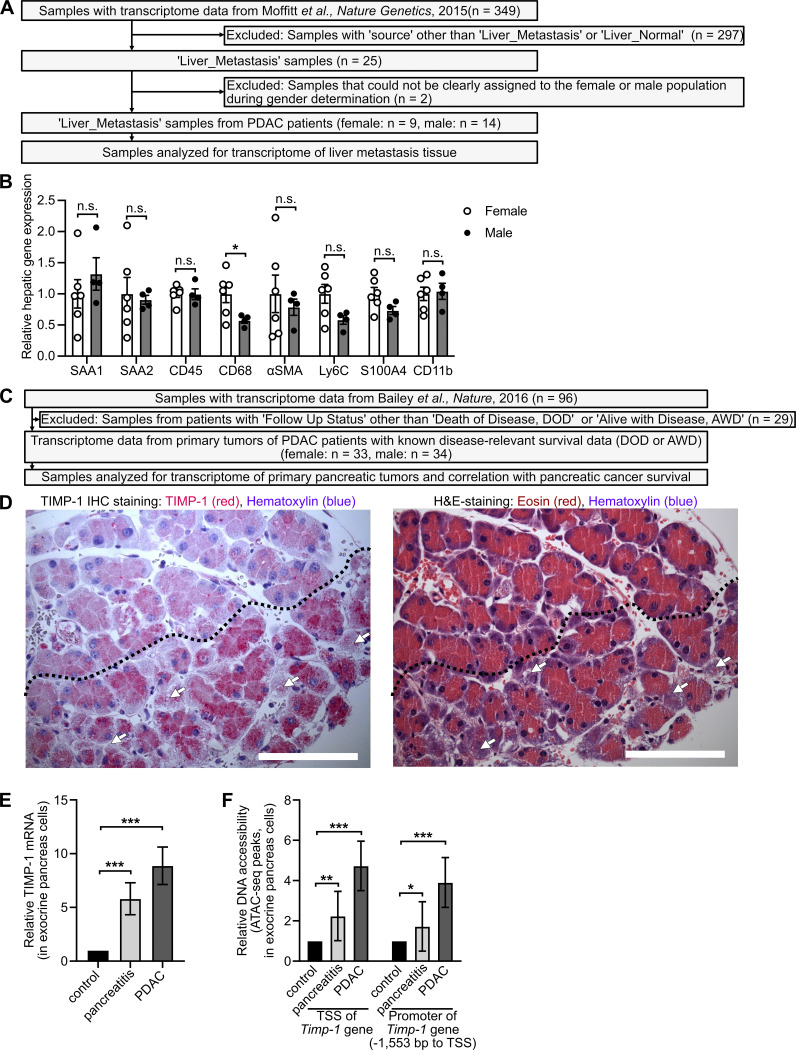

Figure S2.

Inclusion and exclusion of PDAC patients to analyze sex-dependent gene expression in liver and pancreas, sex-dependent metastasis-promoting gene expression in the liver of healthy control mice, and TIMP1 expression in exocrine pancreas cells localized adjacent to injured tissue areas. (A) Of 349 transcriptomic samples from previously published RNA-seq data (Moffitt et al., 2015), 23 samples from liver metastases of PDAC patients were included for analysis of sex-dependent gene expression in PC-primed livers. (B) Relative hepatic mRNA expression of metastasis-promoting genes in healthy female (n = 6) and male (n = 4) control mice. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Mean ± SEM. (C) Of 96 transcriptomic samples from Bailey et al. (2016), 67 samples with known survival data were included for analysis of sex-dependent mRNA expression in PancTs and its correlation with survival. (D) Representative pictures of immunohistochemical (IHC) TIMP1 (red) staining (left) and H&E staining (right) in serial pancreatic tissue sections of a male mouse killed 24 h after the first cerulein injection. TIMP1 expression in exocrine pancreatic cells localized adjacent to damaged cells (arrows) is increased in injured tissue (below dotted line) as compared with noninjured tissue (above dotted line). Scale bars, 100 µm. (E and F) Relative mRNA expression of TIMP1 (E) and relative DNA accessibility of the TSS as well as of a promoter region 1,553 bp upstream of the TSS of the Timp1 gene (F) in exocrine pancreatic cells isolated from control, cerulein-treated (pancreatitis), or PDAC-afflicted (KPflC) male mice. Mean fold change with SE of mRNA expression as well as DNA accessibility data, including statistical information (adjusted P values), were derived from a previously published RNA-seq and ATAC-seq dataset (Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2021), respectively. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (B, E, and F).

Figure 2.

Metastasis-promoting conditioning of PDAC-primed livers occurs in a male-biased manner. (A) GSEA revealed male-specific up-regulation of fibrosis-, immune-, and lipid metabolism–related processes in the liver of PDAC patients. Genes with significant differential expression in the liver tissue of female (n = 9) and male (n = 14) PDAC patients (see Table S1) were employed as a gene list, whereas male versus female fold change in gene expression was used as the gene rank in GSEA. Biological processes (“nodes”) were significantly up-regulated in male livers (NES ≥2.0, FDR q-value ≤0.01), whereas no biological process was detected as down-regulated in male livers (NES ≤2.0, FDR q-value ≤0.01). The size of connections (“edges”) correlates with overlapping genes between the respective nodes. ECM, extracellular matrix; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase. (B) Volcano plot of transcriptomic data showing sex-dependent expression of metastasis-promoting genes (right) in liver metastases of female (n = 9) versus male (n = 14) PDAC patients. Student’s t test was employed to calculate P values. Genes were considered to be significantly up-regulated (red) or down-regulated (blue) in males after Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment (see also Table S1). αSMA, α-smooth muscle actin. (C) The median fold change in hepatic mRNA expression of metastasis-promoting genes of KPC mice with early-stage PDAC (female: n = 3; male: n = 5) normalized to healthy control mice (female: n = 4; male: n = 4). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed for statistics. (D) Quantification of hepatic macrometastases after challenge of control (female: n = 3; male: n = 4) or KPC mice (female: n = 4; male: n = 4) by i.v. inoculation of tumor cells. Data were derived from two independent experiments. Student’s t test and the Mann-Whitney test for independent variables, respectively, were employed for statistics, depending on normal distribution. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (E) Quantification of the proportion of macrometastases in relation to total hepatic metastases (macro- plus micrometastases) after challenge of control (female: n = 5; male: n = 6) or cerulein-treated mice (female: n = 6; male: n = 6) by i.v. inoculation of tumor cells. Data were derived from three independent experiments. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (C–E).

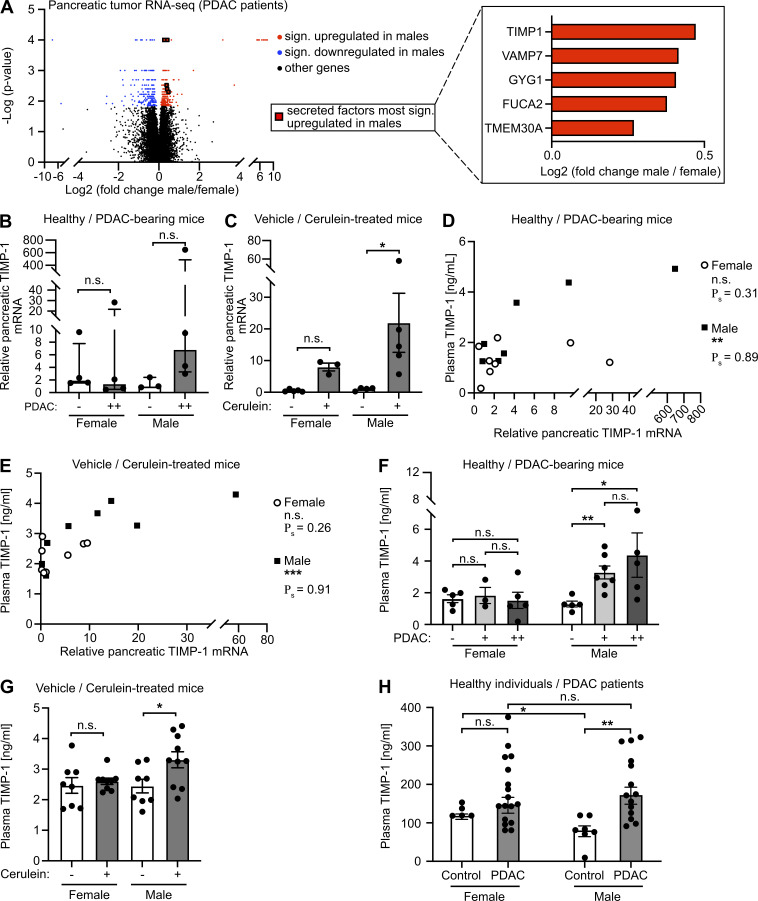

Male-biased pancreatic TIMP1 expression is associated with a male-specific increase of systemic TIMP1 levels in PDAC

Because metastasis-promoting niches in distant organs are induced by TDSFs (Peinado et al., 2017), we next analyzed mRNA expression data from pancreatic primary tumors of female and male PDAC patients (Bailey et al., 2016; Fig. S2 C). Expression of 470 genes in human pancreatic tumors (PancTs) significantly differed between both sexes (Table S2), whereas only a minority of these genes encoded for secreted factors up-regulated in males (Fig. 3 A). Among the most significantly differentially expressed secreted factors, TIMP1, an emerging liver metastasis–promoting factor (Seubert et al., 2015; Grünwald et al., 2016), turned out to be a TDSF with the strongest up-regulation in males versus females (Fig. 3 A, right). Using the spontaneous KPC mouse model for PDAC as well as the experimentally induced pancreatic disease model upon cerulein injection, we observed an up-regulation of pancreatic TIMP1 mRNA expression in diseased compared with healthy male mice (Fig. 3, B and C), whereas females showed no such changes (Fig. 3, B and C). Acinar cells of the exocrine pancreas localized in areas of tissue injury were the major source of disease-induced TIMP1 expression (Fig. S2 D). Evaluation of a published mRNA-sequencing (mRNA-seq) and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) dataset (Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2021) revealed that TIMP1 mRNA expression (Fig. S2 E) and transcriptional accessibility of the Timp1 gene (Fig. S2 F) in exocrine pancreatic cells of male mice were highly up-regulated during PDAC as well as cerulein-induced pancreatic injury.

Figure 3.

Male-biased pancreatic TIMP1 expression is associated with a male-specific increase of TIMP1 plasma levels in pancreatic disease. (A) Volcano plot (left) of transcriptomic data showing sex-dependent gene expression in PancT tissue of female (n = 33) and male (n = 34) PDAC patients. The Mann-Whitney test was employed to calculate P values. Genes were considered to be significantly (sign.) up-regulated (red) or down-regulated (blue) in males after Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment (see also Table S2). Median male versus female fold change expression of genes encoding for secreted factors most significantly up-regulated in males (right). (B and C) Relative pancreatic TIMP1 mRNA expression in healthy female (n = 4) or male (n = 3) mice as well as in PDAC-afflicted female (n = 4) and male (n = 4) KPC mice (−: control mice; ++: advanced PC; B) or in mice treated with (+, female: n = 3; male: n = 5) or without (−, female: n = 5; male: n = 4) cerulein (C), respectively. The Mann-Whitney test (B) and Student’s t test (C) were employed for statistics, respectively. Up-regulation of TIMP1 expression in male KPC mice was close to significant (P = 0.057). Median ± interquartile range (B and C). (D and E) Correlation of relative pancreatic TIMP1 mRNA expression with TIMP1 plasma levels in female (n = 8) or male (n = 7) KPC mice (D) or in female (n = 8) or male (n = 9) mice of the cerulein-based mouse model (E). Spearman’s correlation was employed for statistics. (F) Plasma TIMP1 levels of female (n = 5) and male (n = 5) healthy control or female (+: n = 3; ++: n = 5) and male (+: n = 7; ++: n = 5) KPC mice (−: control mice; +: early PancTs; ++: advanced PC). Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Mean ± SEM. (G) Plasma TIMP1 levels of female and male mice treated with (+, female: n = 9; male: n = 10) or without (−, female: n = 8; male: n = 8) cerulein. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Mean ± SEM. Data were derived from at least three independent cerulein-based mouse experiments (C, E, and G). (H) Plasma TIMP1 levels of female (n = 5) and male (n = 7) healthy control subjects or female (n = 17) and male (n = 14) patients with PDAC (UICC stages I and II). Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Median ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (B–H).

In both, KPC (Fig. 3 D) and cerulein-treated mice (Fig. 3 E), pancreatic TIMP1 mRNA expression positively correlated with plasma levels of TIMP1 in males but not in females (Fig. 3, D and E). Moreover, only male PDAC-afflicted mice showed an increase of plasma TIMP1 levels already at early stages of PDAC (Fig. 3 F) and upon cerulein-induced pancreatic disease (Fig. 3 G). Most important, only male PDAC patients showed a significant increase of TIMP1 in the circulation as compared with healthy control subjects (Fig. 3 H), whereas the baseline of TIMP1 plasma levels in healthy individuals was higher in women (Fig. 3 H), altogether indicating that TIMP1 blood levels should be evaluated separately in women and men.

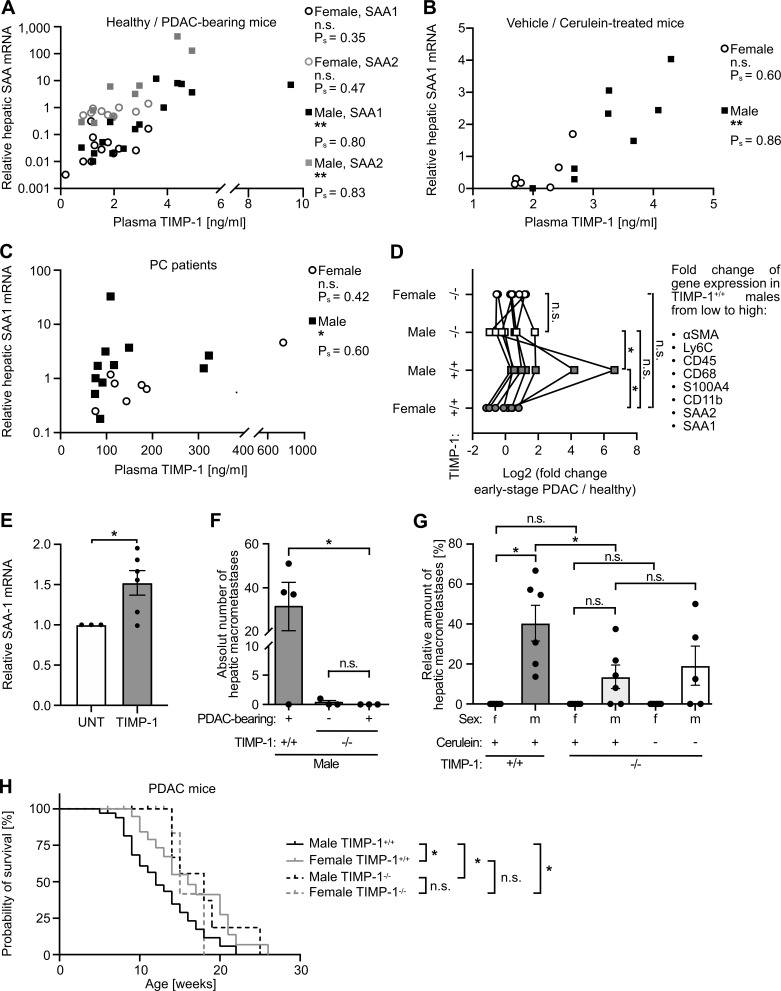

Sex disparity in PC liver metastasis as well as survival is dependent on increased TIMP1 expression in males

We next addressed whether changes of TIMP1 blood levels, as observed in PDAC-afflicted males, are directly associated with altered metastasis-promoting gene expression in the liver. In both the KPC mouse model (Fig. 4 A) and cerulein-treated mice (Fig. 4 B), we found a male-specific significant correlation between TIMP1 in blood plasma and hepatic expression of SAA, the pro-metastatic liver factor with the highest up-regulation in males (Fig. 2 C). Such male-specific correlation of TIMP1 plasma levels with hepatic SAA mRNA expression was furthermore found in PDAC patients (Fig. 4 C). We next tested the causal involvement of TIMP1 in determining sex disparities in PDAC. In fact, genetic ablation of TIMP1 in KPC mice resulted in a complete abrogation of the male-specific metastasis-promoting gene expression signature in the liver (Fig. 4 D). Of note, basal expression of the metastasis-promoting gene signature in the liver in female KPC mice was not affected by TIMP1 ablation (Fig. 4 D). Moreover, TIMP1 was able to directly trigger expression of SAA, a well-known pro-metastatic niche factor in the liver (Lee et al., 2019), in human hepatocytes (Fig. 4 E). This causality was further reiterated on the level of experimental liver metastasis. Challenge of male TIMP1-deficient KPC as well as cerulein-treated mice by i.v. inoculation of tumor cells revealed complete abrogation of increased liver metastasis in males (Fig. 4, F and G). Of note, sex differences in liver metastasis were strictly dependent on TIMP1 expression in PC-afflicted males, because TIMP1-deficient male mice did not differ from TIMP1-competent or TIMP1-deficient female mice with respect to liver metastases (Fig. 4 G). These results unveiled male-specific up-regulation of TIMP1 in PDAC as a driver of male-biased metastasis-promoting conditioning of the liver. In addition, ablation of TIMP1 expression significantly prolonged the survival of PDAC-bearing male mice and abolished the observed sex differences in PDAC survival (Fig. 4 H). Taken together, these findings demonstrate the decisive, causal role of the male-specific increase of TIMP1 for determination of sex disparity in liver metastasis as well as survival in PC.

Figure 4.

Increased liver metastasis and shortened survival of PDAC-afflicted males is TIMP1 dependent. (A and B) Correlation of plasma TIMP1 with hepatic SAA mRNA expression in female (SAA1: n = 12; SAA2: n = 9) and male (SAA1: n = 15; SAA2: n = 9) KPC mice (A) or in female (n = 6) or male (n = 8) mice of the cerulein-based mouse model (B). Data were derived from three independent experiments (B). Spearman’s correlation was employed for statistics. (C) Correlation of plasma TIMP1 with hepatic SAA mRNA expression in female (n = 7) and male (n = 11) PDAC patients. Spearman’s correlation was employed for statistics. (D) Median fold change in hepatic mRNA expression of pro-metastatic genes in TIMP1-competent (+/+) or TIMP1-deficient (−/−) female (+/+: n = 3; −/−: n = 4) and male (+/+: n = 5; −/−: n = 4) KPC mice with PDAC normalized to female (+/+: n = 4; −/−: n = 3) and male (+/+: n = 4; −/−: n = 3) control mice. For the attribution of the individual genes, see also Fig. 2 C. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed for statistics. (E) SAA1 mRNA expression of untreated (UNT; n = 3) or TIMP1-stimulated (n = 6) HepaRG cells. Data were derived from three independent experiments. A one-sample t test against reference value 1 was employed for statistics. Mean ± SEM. (F) Quantification of hepatic macrometastases (right) after challenge of TIMP1-deficient control mice (n = 3) or TIMP1-deficient (n = 3) or TIMP1-competent (n = 4) KPC mice by i.v. inoculation of tumor cells. Data were derived from two independent experiments. The Mann-Whitney test was employed for statistics. Mean ± SEM. (G) Quantification of the proportion of macrometastases in relation to total hepatic metastases (macro- plus micrometastases) after challenge of TIMP1-deficient female (n = 6) or male (n = 5) control mice or TIMP1-deficient (−/−) or TIMP1-competent (+/+) cerulein-treated female (−/− and +/+: n = 6) and male (−/− and +/+: n = 6) mice by i.v. inoculation of tumor cells. Data were derived from three independent experiments. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Mean ± SEM. (H) Overall survival of TIMP1-competent PDAC-bearing female (n = 22) and male (n = 34) mice and of TIMP1-deficient female (n = 11) and male (n = 11) PDAC-bearing mice. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. Ρs, Spearman’s correlation coefficient; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01 (A–H).

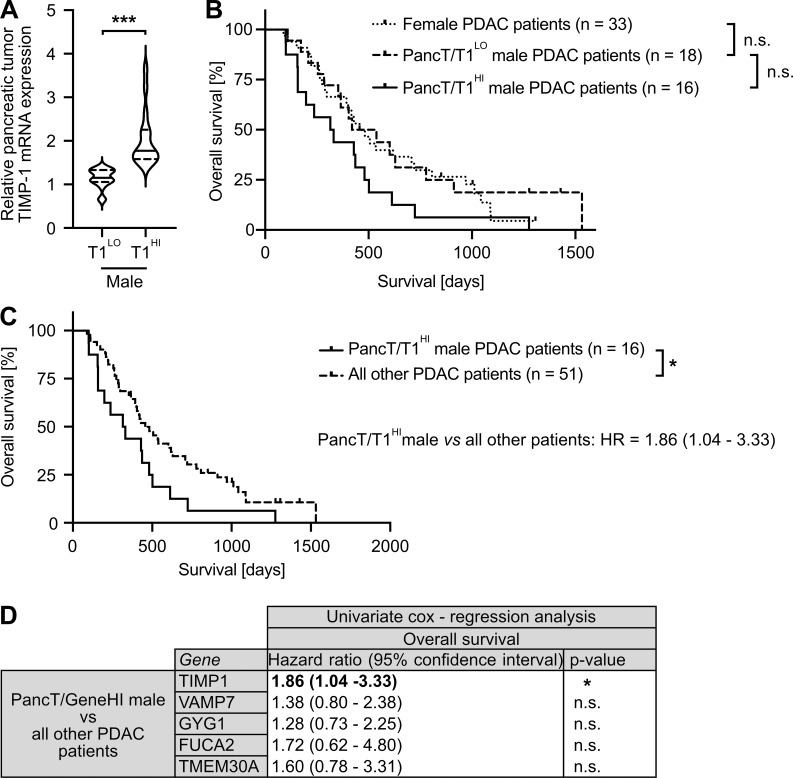

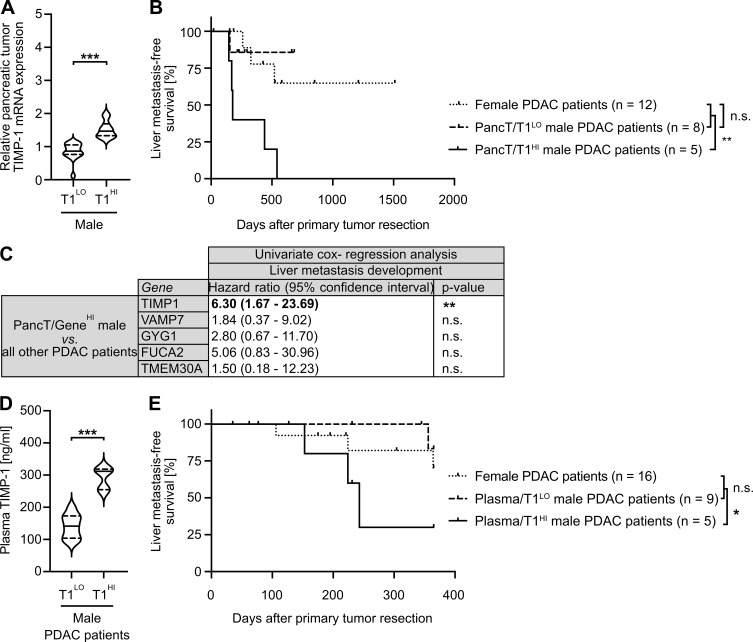

A subpopulation of male PDAC patients with increased TIMP1 expression (T1HI males) accounts for sex differences in PDAC survival

Based on our observation that increased TIMP1 expression was a risk parameter in PDAC-afflicted male mice, we next investigated a possible clinical value of TIMP1 in male PDAC patients. Two-step cluster analysis uncovered two separate groups within the male population (Fig. 5 A). One subgroup exhibited significantly increased TIMP1 mRNA expression in PancTs (PancT/T1HI) as compared with all other males (PancT/T1LO). Interestingly, the PancT/T1HI subgroup of males showed close to significant shorter overall survival than PancT/T1LO males (Fig. 5 B). Because overall survival of PancT/T1LO males and female PDAC patients did not differ (Fig. 5 B), these patients were grouped as one population for comparison of their survival with the group of PancT/T1HI males (Fig. 5 C). These findings indicate that sex differences in PDAC survival are caused by one particular male subpopulation exhibiting increased PancT TIMP1 expression (PancT/T1HI males). In fact, PancT/T1HI males exhibited a 1.86-fold increased risk of death as compared with all other PDAC patients (PancT/T1LO males and female; Fig. 5 C). Notably, clustering of male PDAC patients based on the other identified secreted factors with male-biased primary tumor expression (VAMP7, GYG1, FUCA2, TMEM30A) did not reveal differences in survival (Fig. 5 D). In accordance with the observation that TIMP1 did not affect survival in female PDAC-afflicted mice (Fig. 4 H), TIMP1 expression was not prognostic in female PDAC patients (Fig. S3 A). Taken together, these findings identify a high-risk male subpopulation in PDAC.

Figure 5.

Identification of a subpopulation of male PDAC patients with increased TIMP1 expression in PancTs accounting for sex differences in PDAC survival. (A) TIMP1 mRNA expression in the pancreatic primary tumors of male PDAC patients separated by two-step cluster analysis into males with low (T1LO; n = 18) or high (T1HI; n = 16) TIMP1 expression. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. (B) Probability of overall survival of female (n = 33) or male PDAC patients with low (PancT/T1LO; n = 18) or high (PancT/T1HI; n = 16) TIMP1 mRNA expression in pancreatic primary tumors. Log-rank statistics were employed for statistics. The difference in overall survival between PancT/T1LO and PancT/T1HI male PDAC patients was close to significant (P = 0.052). (C) Probability of overall survival of male PDAC patients with high TIMP1 mRNA expression in the pancreatic primary tumor (PancT/T1HI; n = 16) compared with all other patients (n = 51). Log-rank statistics were employed for statistics. HRs with 95% confidence intervals were determined by Cox regression analysis between PancT/T1HI males and all other PDAC patients. (D) HRs with 95% confidence intervals for overall survival between a subpopulation of male PDAC patients with increased expression of TIMP1, VAMP7, GYG1, FUCA1, or TMEM30A (determined by two-step cluster analysis) and all other PDAC patients, respectively. Cox regression analysis was employed for statistics. *, P ≤ 0.05; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (A–D).

Figure S3.

Liver metastasis development in female PDAC patients separated by TIMP1 as well as inclusion and exclusion of PDAC patients for analysis of liver metastasis development. (A) Probability of overall survival of female PDAC patients with low (PancT/T1LO; n = 28) or high (PancT/T1HI; n = 5) TIMP1 mRNA expression in the pancreatic primary tumor. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. (B) Of 183 samples from FireBrowse.org (PAAD), 25 samples from patients with early-stage nonmetastatic PC treated with margin-negative primary tumor resection and subsequent chemotherapy were included for analysis of liver metastasis development after primary tumor resection. TNM, tumor, node, metastasis. (C) Of 493 total participants, 31 patients diagnosed with early-stage nonmetastatic PDAC and known blood TIMP1 levels were analyzed for liver metastasis development after primary tumor resection.

T1HI male PDAC patients show earlier development of liver metastases after PancT resection

Based on our observation that increased TIMP1 expression determined increased liver metastasis in PDAC-afflicted male mice (Fig. 4, F and G), we next examined whether increased TIMP1 mRNA expression in PancTs could also be used to predict liver metastasis in male PDAC patients. For this purpose, we employed transcriptomic data with pertinent information about liver metastasis development (Fig. S3 B). To control for disease stage and treatment within the cohort of PDAC patients, we included potentially curable patients (Neoptolemos et al., 2018) without synchronous metastases (M0 status) who were treated with margin-negative primary tumor resection (R0 status) and subsequent chemotherapy (Fig. S3 B). Here (Fig. 6 A), two-step cluster analysis confirmed the existence of the male (PancT/T1HI) subgroup (Fig. 5 B). Importantly, although liver metastasis development in PancT/T1LO male patients was the same as in female PDAC patients (Fig. 6 B), PancT/T1HI male PDAC patients developed liver metastases significantly earlier after primary tumor resection than all other PDAC patients (Fig. 6 B). Of note, clustering of male PDAC patients based on the other previously identified secreted factors with male-biased primary tumor expression (VAMP7, GYG1, FUCA2, TMEM30A) did not reveal differences in liver metastasis development (Fig. 6 C). In light of our finding that pancreatic TIMP1 mRNA expression closely correlated with plasma TIMP1 levels in PDAC-afflicted males (Fig. 3, D and E), we next analyzed the predictive value of TIMP1 in the more easily accessible blood plasma. In stage-matched PDAC patients, who did not exhibit clinically detectable metastases at the time point of diagnosis (M0 status) and were therefore treated with potentially curable primary tumor resection (Fig. S3 C), two-step cluster analysis again revealed a subgroup of males with increased plasma TIMP1 levels (plasma/T1HI cutoff >200 ng/ml TIMP1) as compared with all other male PDAC patients (plasma/T1LO cutoff <200 ng/ml TIMP1; Fig. 6 D). In fact, plasma/T1HI male PDAC patients developed overt liver metastases significantly earlier than all other PDAC patients (plasma/T1LO males or females, who did not differ in liver metastasis development; Fig. 6 E).

Figure 6.

A subpopulation of male PDAC patients with increased TIMP1 levels show earlier development of metastases specifically in the liver. (A) TIMP1 mRNA expression in pancreatic primary tumors of male PDAC patients separated by two-step cluster analysis into males with low (T1LO; n = 16) or high (T1HI; n = 11) TIMP1 expression. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Medians (continuous lines) and interquartile ranges (dotted lines). (B) Probability of liver metastasis–free survival of male PDAC patients (M0, R0) with high TIMP1 mRNA expression in the pancreatic primary tumor (PancT/T1HI; n = 5) compared with all other patients (combined female and T1LO males; n = 20). The log-rank test was employed for statistics. (C) HRs including 95% confidence intervals for liver metastasis–free survival between a subpopulation of male PDAC patients with increased expression of TIMP1, VAMP7, GYG1, FUCA1, or TMEM30A (determined by two-step cluster analysis) and all other PDAC patients, respectively. Cox regression analysis was employed for statistics. (D) Plasma TIMP1 levels of male PDAC patients separated by two-step cluster analysis into males with low (Plasma/T1LO; n = 9) or high (Plasma/T1HI; n = 5) plasma TIMP1 levels, respectively. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Medians (continuous lines) and interquartile ranges (dotted lines). (E) Probability of liver metastasis–free survival of male PDAC patients with high TIMP1 plasma levels (Plasma/T1HI; n = 5) as compared with all other patients (combined female and Plasma/T1LO males; n = 25). The log-rank test was employed for statistics. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (A–E).

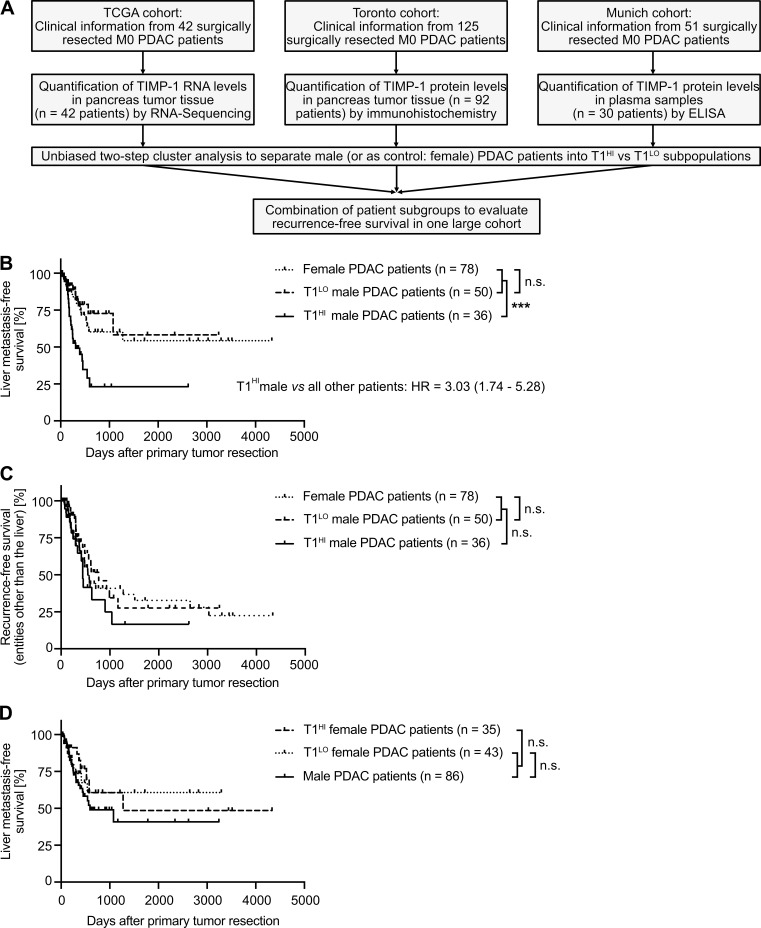

Validation of the male-specific clinical value of TIMP1 to predict liver metastasis in PDAC

Our analyses clearly demonstrated that in cohorts of stage-matched, treatment-matched, and resection status–matched PDAC patients, which enabled minimization of possible confounder effects, a subpopulation of males clustered by increased TIMP1 levels in both PancTs and blood plasma was at high risk for developing liver metastases after primary tumor resection. We validated this finding in clinical data encompassing resected PDAC patients from three independent cohorts (Fig. 7 A). Although T1LO male and female PDAC patients again showed comparable liver metastasis development (Fig. 7 B), T1HI males had a highly significantly and more than threefold increased risk of developing liver metastases after primary tumor resection (Fig. 7 B). Importantly, the predictive value of TIMP1 in primary tumor-resected male PDAC patients was specific for liver metastasis development, because T1HI males did not show differences in disease recurrence in entities other than the liver (i.e., pancreas, peritoneum, LN, or lung) as compared with all other PDAC patients (Fig. 7 C). Substantiating our initial findings that TIMP1 promotes liver metastasis formation in a male-specific manner (Fig. 4, D and G), TIMP1 expression had no predictive value in female PDAC patients (Fig. 7 D). As a proof of the concept that TIMP1 expression should be evaluated separately in women and men (Fig. 3 H), separation of PDAC patients only according to TIMP1 levels did not reveal significant differences in liver metastasis development (Fig. S4 A) as a result of grouping high-risk T1HI males with low-risk T1HI female patients as a mixed population (Fig. S4 B). Taken together, these data indicate that the subpopulation of male PDAC patients with increased TIMP1 expression and severely increased risk of developing liver metastases (T1HI males) accounts for the observed sex differences in liver metastasis formation of PDAC (Fig. 1 K).

Figure 7.

Validation of the male-specific clinical value of TIMP1 to predict metastasis development specifically in the liver of primary tumor-resected PDAC patients across multiple patient cohorts. (A) Combination of clinical data from primary tumor resected PDAC patients from three independent studies/cancer centers by (1) quantification of TIMP1 in pancreatic tumors on the level of mRNA (TCGA cohort) or protein (Toronto cohort) or in blood plasma (Munich cohort), (2) clustering of patients based on TIMP1 levels in each cohort via two-step cluster analysis, and (3) grouping of T1HI or T1LO patients from each cohort in one combined population. (B and C) Probability of recurrence-free survival in the liver (B) or in entities other than the liver (i.e., pancreas, LN, lung, peritoneum; C) of female (n = 78), T1LO (n = 50), or T1HI (n = 36) male PDAC patients. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. HRs with 95% confidence intervals were determined by Cox regression analysis between T1HI males and all other PDAC patients. (D) Probability of liver metastasis-free survival of male (n = 86), T1LO (n = 43), or T1HI (n = 35) female PDAC patients. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. ***, P ≤ 0.001 (A–D).

Figure S4.

Liver metastasis development in all PDAC patients separated by TIMP1, inclusion and exclusion of CRC and SKCM patients for analysis of liver metastasis development, histology of pancreatic lesions in the cerulein mouse model, and histology of micro- and macrometastases after experimental metastasis assays. (A and B) Probability of liver metastasis–free survival of all PDAC patients (males and females combined in A or subsequently subdivided by sex in B) separated by two-step cluster analysis according to high (female: n = 35; male: n = 33) or low (female: n = 43; male: n = 53) TIMP1 levels, respectively. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. HR with 95% confidence interval was determined by Cox regression analysis. (C and D) Inclusion and exclusion of stage-matched CRC (C) and SKCM (D) patients, respectively, for analysis of liver metastasis development. (E) Representative pictures of H&E staining of pancreatic tissue from cerulein-treated (pancreatitis) or vehicle-treated (control) mice killed 24 h after the first injection. Acinus cell injury is highlighted (arrows). Scale bars, 100 µm. (F) Representative pictures of an X-Gal–stained (blue) hepatic micrometastasis (upper panel) and macrometastasis (center panel), as well as a representative picture of H&E staining of a hepatic macrometastasis (lower panel), respectively. Scale bars, 250 µm (upper and center panels), 100 µm (lower panel). (G) List of genes with corresponding primer sequences and probes employed to perform real-time quantitative RT-PCR. (H) Sex determination of transcriptomic data from human liver metastases. Two-step cluster analysis of RNA-seq data from liver metastases (n = 25; Moffitt et al., 2015) based on relative DDX3Y (left) or XIST (center) expression resulted in the separation of two clusters with high (HI) or low (LO) expression, respectively. Combination of both two-cluster analyses revealed three populations (right). Population 1 (n = 14) had high expression of DDX3Y, a Y chromosome–encoded gene, and low expression of XIST, an X chromosome–encoded gene involved in X chromosome inactivation, which we identified as the male population. Population 2 (n = 9) had low expression of DDX3Y and high expression of XIST, which we identified as the female population. Population 3 (n = 2) had low expression of both genes, DDX3Y and XIST, and was excluded from further analyses because the sex of these two individuals could not be determined conclusively. ***, P ≤ 0.001 (A and B).

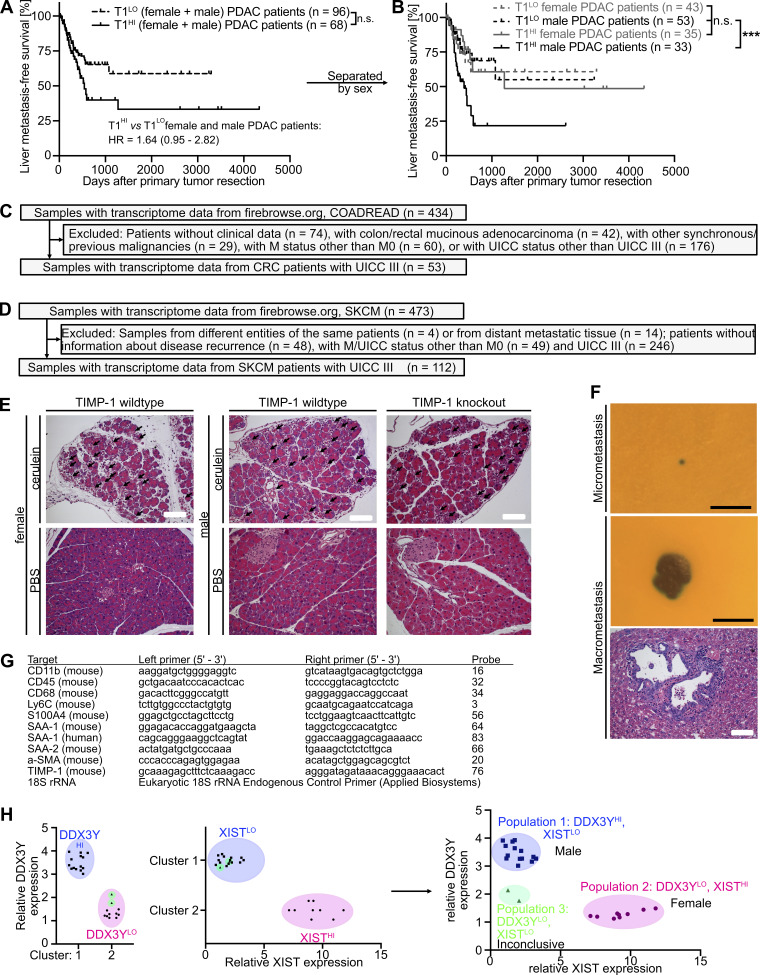

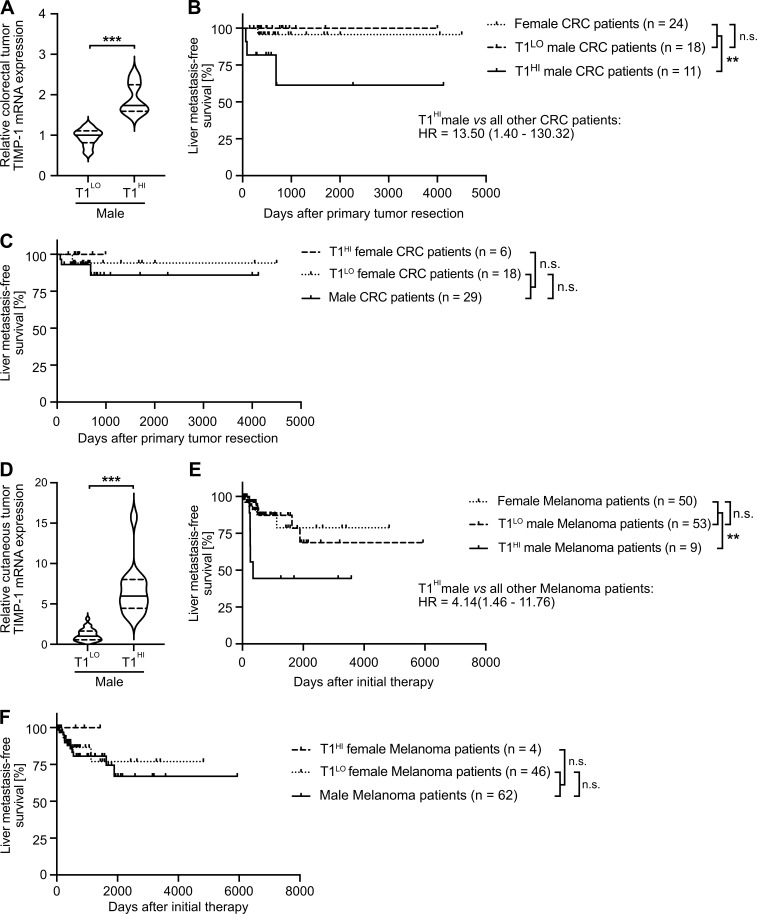

T1HI male patients show earlier liver metastasis development in colorectal cancer (CRC) and melanoma

Toward generalization, we analyzed liver metastasis development in patients diagnosed with CRC. To minimize possible confounder effects, we employed stage-matched CRC patients who were diagnosed without synchronous metastases and were treated with primary tumor resection (Fig. S4 C). Similar to our findings in the context of PDAC, two-step cluster analysis revealed a subgroup of male CRC patients with increased TIMP1 mRNA expression in colorectal tumors (T1HI) as compared with all other male patients (T1LO; Fig. 8 A). Although T1LO male and female CRC patients showed comparably low risk for liver metastasis development after primary tumor resection (Fig. 8 B), T1HI males exhibited an ∼13.5-fold increased risk of developing liver metastases as compared with all other CRC patients (Fig. 8 B). Notably, TIMP1 expression also had no predictive value in female CRC patients (Fig. 8 C). In another cancer type of distinctively different origin, namely skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM; Figs. 8 D and S4 D), T1LO male and female SKCM patients also did not differ in liver metastasis development (Fig. 8 E), whereas stage-matched T1HI males again developed liver metastases earlier than all other SKCM patients (Fig. 8 E). Notably, TIMP1 expression also did not have predictive value in female SKCM patients (Fig. 8 F), altogether confirming an association of TIMP1 with male-specific liver metastasis in PDAC, CRC, and SKCM.

Figure 8.

Increased TIMP1 expression in tumors of male CRC or SKCM patients predicts early development of liver metastases. (A and D) TIMP1 mRNA expression in primary tumors of male CRC (A) or SKCM (D) patients separated by two-step cluster analysis into males with low (CRC: T1LO, n = 18; SKCM: T1LO, n = 53) or high (CRC: T1HI, n = 11; SKCM: T1HI, n = 9) TIMP1 expression. Student’s t test was employed for statistics. Medians (continuous lines) and interquartile ranges (dotted lines). (B and E) Probability of liver metastasis–free survival of male CRC (B) or SKCM (E) patients with high TIMP1 expression (CRC: T1HI, n = 11; SKCM: T1HI, n = 9) compared with all other patients (CRC: n = 42; SKCM: n = 103), respectively. The log-rank test was employed for statistics. HRs with 95% confidence intervals were determined by Cox regression analysis between T1HI males and all other patients. (C and F) Probability of liver metastasis–free survival of female CRC (C) or SKCM (F) patients with high TIMP1 expression (CRC: T1HI, n = 6; SKCM: T1HI, n = 4) compared with all other patients (CRC: n = 47; SKCM: n = 108). The log-rank test was employed for statistics. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (A–F).

Discussion

This study identified TIMP1 as an intrinsic factor driving a sex disparity in liver metastasis as well as survival of PDAC. Previously, decreased survival of males in cancer was often trivialized as being a consequence of variation in lifestyle between females and males (Clocchiatti et al., 2016), because lifestyle-associated factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and unhealthy diet are generally more prevalent in the male population (Kelly et al., 2008; Rehm et al., 2009; GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators, 2017) and were shown to correlate with decreased survival in cancer (Park et al., 2006). In fact, by using genetically engineered mouse models, we here demonstrated the existence of lifestyle-independent sex differences in PDAC survival. Although it is not possible to strictly control for lifestyle in patient cohorts, housing of PDAC-afflicted mice was standardized, and exposure to extrinsic risk factors was absent. The consistent presence of a sex disparity in PDAC-afflicted patients and mice serves as proof of the concepts that sex-dependent intrinsic factors play a key role in determining poor cancer outcome (Clocchiatti et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2019) and that sex differences in cancer survival cannot be explained by lifestyle differences alone between females and males (Micheli et al., 2009).

In contrast to previous studies that pointed to sex disparity only with regard to survival (Micheli et al., 2009; Radkiewicz et al., 2017), our present study for the first time demonstrated specific sex differences in metastasis formation. Intriguingly, among the four most afflicted sites of distant PDAC metastasis (Budczies et al., 2015), male-specific increase of metastasis was a liver-specific effect. In contrast, no sex-related differences in PancT recurrence or distant metastasis development were observed in the lung, peritoneum, or LNs. Clearly, it is impossible to exclusively explain sex differences in survival by sex differences in liver metastasis, because the ultimate cause of death in cancer-afflicted individuals is often multifactorial (Ambrus et al., 1975). Still, the sex disparity in PDAC survival described here was strongly linked with liver-specific sex differences in metastasis, and the liver is by far the most frequently afflicted site of PDAC metastasis in patients (Oweira et al., 2017) and mice (Hingorani et al., 2005). In addition, hepatic metastases are presumed to account for the majority of PDAC deaths (Ryan et al., 2014) because they are associated with significantly shorter survival than PDAC metastases in other organs (Oweira et al., 2017). The clear association of TIMP1-determined sex disparity in both PDAC survival and liver metastasis hence strongly suggests a causal link between the two findings.

Sex differences in metastasis of one specific organ, namely the liver, pointed toward metastasis-promoting conditioning of the liver as a basis for these sex disparities, because the metastatic organotropism of cancer is driven by the formation of organ-specific metastasis-promoting niches (Hoshino et al., 2015). In our study, transcriptomic analysis of patient-derived liver tissue indeed indicated a male-biased metastasis-promoting reprogramming of this organ. Such reprogramming of the liver tissue was shown to be a key process enabling efficient liver metastasis in PDAC-afflicted mice (Grünwald et al., 2016; Nielsen et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019). Male-specific metastasis-promoting conditioning of the liver would be an explanation for the high proportion of male PDAC patients with overt liver metastases at the time point of diagnosis described here.

We here identified, in the clinical context, TIMP1 as a driver of male-biased liver metastasis in PDAC. So far, the metastasis-facilitating effect of TIMP1 was shown in mouse models only and relied on alteration of liver homeostasis by TIMP1 (Seubert et al., 2015; Grünwald et al., 2016). However, the clinical relevance, as well as a possible sex dependency of TIMP1-induced liver metastasis, was so far unknown. Here, we found that shortened survival of PDAC-afflicted males, male-biased liver metastasis, and pro-metastatic reprogramming of the liver in the presence of PDAC are dependent on male-specific up-regulation of TIMP1. In fact, an increase of circulating protein levels during cancer disease is a prerequisite for metastasis-supporting preconditioning of distant organs by TDSFs, because TDSFs can act on distant organs only via the bloodstream (Peinado et al., 2017). Therefore, the increase of TIMP1 plasma levels only in male, and not in female, PDAC-afflicted mice as well as patients is in agreement with the observed TIMP1-dependent sex disparity in liver metastasis. At first sight, the finding that TIMP1 was up-regulated in a male-specific manner was surprising, because TIMP1 is an X chromosome–encoded gene (Jackson et al., 2017). In fact, increased TIMP1 mRNA expression in acinar cells from male mice was associated with a better accessibility of the Timp1 gene promoter, indicating that epigenetic changes in acinar cells play a key role in up-regulation of TIMP1 expression during pancreatic diseases. A recent study indeed demonstrated that epigenetic changes in pancreatic epithelial cells occur very early during inflammatory conditions in the pancreas and that these changes play a key role in subsequent progression of benign lesions to invasive PDAC (Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2021). In fact, sex disparities in epigenetics are well known to account for sex differences in cancer disease (Credendino et al., 2020). Therefore, further detailed epigenetic studies will help to address the molecular basis of male-specifically increased pancreatic TIMP1 expression during PDAC. Altogether, we here identified TIMP1 as a sex chromosome–encoded factor regulating sex differences in cancer, a concept that was previously suggested (Clocchiatti et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2019).

Our observation of TIMP1 as one driver of increased liver metastasis in males led to identification of a clinical subgroup that accounted for the existence of sex disparities in PDAC. This subgroup within the male population exhibited increased TIMP1 levels in tumor or plasma and showed remarkably earlier liver metastasis as well as shorter survival than all other PDAC patients. The causal relationship between TIMP1 expression and male-biased metastasis was demonstrated by using genetically engineered mouse models where TIMP1 was ablated in PDAC-afflicted male mice. Such a determining impact of TIMP1 for sex disparity in liver metastasis also became evident in PDAC patients when we excluded a subgroup of male patients exhibiting high levels of TIMP1 resulting in an abrogation of sex disparity.

Regarding clinical applicability arising from our findings, TIMP1 may be a promising biomarker candidate in male PDAC patients. For example, in cases of PancT resection, one could suggest quantifying TIMP1 in order to identify potentially curable PDAC patients (Neoptolemos et al., 2018) with increased risk of developing liver metastases (T1HI males). Importantly, we were able to identify high-risk patients in three independent cohorts with primary tumor–resected PDAC patients. Male PDAC patients with increased TIMP1 levels had a markedly, approximately threefold increased risk of disease recurrence in the liver as compared with all other PDAC patients. A possible confounder effect due to disease stage or treatment is rather unlikely, because tumor, node, metastasis status, and Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) status as well as treatment regimen were comparable between male and female populations in the PDAC patient cohorts employed here. In fact, development of metastasis in the liver is the earliest and most frequent type of disease recurrence (Groot et al., 2018) as well as the major cause of death (Hishinuma et al., 2006) observed in PDAC patients after potentially curable primary tumor resection. Recent appeals have highlighted the clinical necessity to identify subgroups of PDAC patients with potentially curable disease stage and an increased risk for disease progression, because these high-risk groups may be monitored more precisely and treated as early as possible (Neoptolemos et al., 2018). So far known predictors of disease recurrence after primary tumor resection in PDAC patients were based on histological examination of tumor tissue specimens and rather unspecifically predicted disease recurrence in any entity (Groot et al., 2018). Here, we provide a promising candidate, namely TIMP1, that can easily be quantified either in resected primary tumor tissue or in minimally invasive blood samples and that may predict disease recurrence specifically in the liver of PDAC patients. Of note, we demonstrated that basal TIMP1 blood levels in healthy women were higher than in healthy men. Therefore, although TIMP1 plasma levels did not increase in female PDAC patients as compared with healthy females, increased plasma TIMP1 levels of male PDAC patients were in a range comparable to those in female individuals. Accordingly, we propose to, first, consider the sex of PDAC patients and separately compare female with male patients and, second, quantify TIMP1 in the plasma of male PDAC patients to assess whether they are at increased risk of developing liver metastases (T1HI males, >200 ng/ml plasma TIMP1) or not (T1LO males). If further studies substantiate the clinical usefulness of TIMP1 as a male-specific predictor of liver metastases in larger patient cohorts, the resulting clinical consequence would be that T1HI male PDAC patients may be treated earlier, and potentially even before clinical manifestation of liver metastases, with therapies specifically targeting metastatic PDAC disease in the liver (Neoptolemos et al., 2018; Petrowsky et al., 2020).

In addition to PDAC, the poor prognosis cluster of male patients with increased tumoral TIMP1 mRNA expression was also found in CRC and SKCM. Likewise in PDAC, these T1HI male patients exhibited a considerably higher risk for liver metastases than their stage-matched T1LO and/or female counterparts, suggesting that the predictive value of TIMP1 expression for the development of metastases in the liver of males extends from PDAC to other cancer entities. In fact, CRC is the cancer accounting for the most liver metastases across all cancer types (de Ridder et al., 2016). Therefore, a candidate biomarker, namely TIMP1, for predicting liver metastases in male CRC patients could prove exceptionally valuable.

The impact of sex on disease biology and treatment outcomes is well appreciated in other medical disciplines, such as cardiology, whereas its relevance in oncology was thus far underestimated in both the clinical care of cancer patients (Wagner et al., 2019) and preclinical cancer research (Haupt et al., 2021). The sex differences elucidated here in PDAC survival and liver metastasis caused by the sex-biased expression of an intrinsic factor address an urgent need for a better understanding of the basic components of sex disparities in cancer (Haupt et al., 2021).

Materials and methods

Patients and clinical samples

The Munich cohort

The Munich cohort was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Technical University Munich (1946/07, 409/16S, registered in the German Clinical Trials Register with identifier DRKS00017285). Written consent was obtained from all participants before surgery or before blood sampling, and all participants agreed to participate in this study. The analysis was conducted on a pseudonymized dataset. The study population comprised patients with PC who underwent oncological treatment (staging or resection) between 2009 and 2019 in the Department of Surgery, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University Munich (Fig. S1, A and B; and Fig. S3 C) as well as individuals without a current history of inflammatory or tumor disease (e.g., hernia) who were considered as healthy control subjects. Diagnosis of PC patients was verified by definitive histological examination of surgical specimens or retrieved biopsies or, in PC patients without surgery, by cytology or clinical/radiological information. We used the eighth edition of the UICC tumor, node, metastasis classification and staging system for PC (Brierley et al., 2016). Metastases in the liver, lung, peritoneum, or LNs were assessed by computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and/or surgical exploration. LN metastases were defined as node status N2 (i.e., the presence of metastases in four or more regional LNs). Of note, PC patients employed in all investigations were diagnosed with PDAC. Some metastasis-bearing PC patients (Fig. 1, C–F) were treated without surgery, and therefore lack of histology-based diagnosis of the primary tumor led to less–well-defined cohorts comprising patients with PDAC and possibly other types of PC. Blood was collected in a 2.7-ml EDTA-coated tube (S-Monovette; Sarstedt) and mixed immediately by gently inverting the tube after collection. Blood plasma was obtained within 30 min by centrifugation of whole blood for 15 min at 1,000 g. Plasma samples were immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

The Toronto cohort

The Toronto cohort included 125 individuals with a confirmed histological diagnosis of resectable PDAC (stage I/II, M0) recruited through the University Health Network Biospecimen Services Program (Fig. S1 B). All patients provided written informed consent allowing follow-up on their clinical information. Patient samples were accrued at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre at the University Health Network (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and reported in previous studies (Connor et al., 2019; Romero et al., 2020). All studies were approved by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (03-0049, 15-9596, 17-6106) and complied with all relevant ethical regulations.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data retrieval

The TCGA cohort consisted of 42 PDAC patients (Figs. 7 A and S3 B) from the TCGA data portal (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2017). The TCGA data (National Cancer Institute Genomic Data Commons Data Portal: https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov; project ID accession no. TCGA-PAAD) were accessed via the FireBrowse database (http://firebrowse.org; Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma PAAD cohort).

ECIS survival data

Survival data of PC patients were obtained from the ECIS database (https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu; accessed on January 29, 2020) by selections of “European average” population, “pancreas” as the cancer type, age “15+,” year range of 2000–2007, and indicator “Survival.” Relative 1-, 3-, and 5-yr survival rates of an age-standardized cohort was compared between female (n = 101,357) and male (n = 101,227) PC patients.

Animal models and experiments

Animal experiments were performed according to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines and in compliance with the Tierschutzgesetz des Freistaates Bayern and approved by the Regierung von Oberbayern. Mice of both sexes were employed in this study and were kept at the animal facility of Klinikum rechts der Isar (Munich, Germany) at room temperature (21°C) under specific pathogen–free conditions. All mice were maintained in filter-topped cages on autoclaved food and water.

The transgenic PDAC mouse model KPC (C57BL/6 background) used in this study was described in detail elsewhere (Hingorani et al., 2005). To study the role of TIMP1 in this mouse model, KPC mice were bred into TIMP1-deficient C57BL/6.129S4-TIMP1tm1Pds/J mice (TIMP1−/−; The Jackson Laboratory) to obtain KPC-TIMP1−/− mice (Grünwald et al., 2016). To enable and ensure the comparison of PancT-bearing mice with histologically identical disease progression stages in the KPC mouse model, classification and grading of murine PDAC lesions derived from KPC mice was performed according to the most recent consensus classification by experienced comparative pathologists (K. Steiger and N. Wirges) blinded to sample identity. KPC mice with PDAC grades G2 and/or G3 were classified as advanced-stage PDAC, whereas mice with pancreatic remodeling that did not exhibit invasive PDAC G2/G3 lesions but had only preinvasive lesions were classified as early PancTs. Mice resulting from breeding of the respective KPC strain, which did not carry Pdx-1+/Cre but had only Kras+/LSL-G12D and/or Trp53+/LSL-R172H-mutations or which did only carry Pdx-1+/Cre or no mutation at all, served as control animals.

As a second mouse model, the experimentally inducible and more controllable pancreatic disease model upon cerulein injection was employed. Cerulein-treated mice recapitulate inflammatory conditions in the pancreas, which can precede PC manifestation (Hruban et al., 2008; Kirkegård et al., 2018; Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2021). For this, 50 µg/kg body weight cerulein (C9026; Merck) dissolved in PBS (Merck) was repetitively injected i.p. for 8 h with 1 h between each injection into WT C57BL/6J mice (Charles River) or TIMP1−/− mice (in-house breeding, C57BL/6 background) aged between 6 and 9 wk. Vehicle-treated mice served as control animals. In TIMP1-competent female and male mice as well as in TIMP1-deficient male mice, the histological phenotype of pancreatic injury was comparable (Fig. S4 E).

For i.v. inoculation of tumor cells, mice were prewarmed under red light for 5 min to widen the vasculature. Hepatic susceptibility for PDAC cells was probed by i.v. (tail vein) inoculation of 106 syngeneic KPC-derived 9801 cells suspended in 100 µl PBS. Mice were sacrificed 14 d after tumor cell inoculation. All metastases with a diameter <50 µm were defined as micrometastases (Fig. S4 F, upper panel), whereas metastases with >50-µm diameter were defined as macrometastases (Fig. S4 F, center and lower panels). Quantification of micro- and macrometastases was performed in a blinded manner. Hepatic macrometastases were quantified either as total amounts (for KPC mice) or as the proportion of macrometastases in relation to total hepatic metastases (macro- plus micrometastases) in the more controllable setting of the cerulein-based mouse model. KPC mice were employed in experimental metastasis assays at the age of 10–11 wk, when they typically exhibit early PancTs. Tumor cell inoculation was performed 24 h after the first cerulein/vehicle injection for the cerulein-based mouse model. For visualization of liver metastases, the medial liver lobe was fixed for 1 h at 4°C in 2% neutral buffered formalin solution with 0.2% glutaraldehyde. After washing three times with PBS, the medial liver lobe was covered with ready-to-use X-Gal solution (40 mg/ml X-Gal Thermo Fisher Scientific) in dimethylformamide (Merck) diluted 1:40 in 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6 × 3 H2O, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% (wt/vol) sodium deoxycholate (AppliChem), 0.02% (vol/vol) NP-40 (Merck) in PBS at pH 7.1 and incubated for 2 h at 37°C, then overnight at 4°C. After washing twice with PBS, stained medial liver lobes were covered with 2% neutral buffered formalin solution and stored at 4°C until microscopic evaluation (Olympus SZX 12; Olympus).

Blood was taken from sacrificed mice with an EDTA-coated syringe and immediately centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min at 4°C. Plasma samples were immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. After blood collection, murine liver tissue for RNA expression analysis was taken and immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Mouse pancreatic tissues were fixed in 2% neutral buffered formalin solution for 48 h, dehydrated under standard conditions (Leica ASP300S), and embedded in paraffin. Serial 2-µm sections were prepared with a rotary microtome (HM355S; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed histologically by H&E staining and immunohistochemistry. H&E staining was performed on deparaffinized sections according to a standardized protocol by the Institute of Pathology, Technical University of Munich, Germany.

For Kaplan-Meier analysis, KPC mice were scored according to the animal ethics approval, and mice that reached tumor disease–related ethical stop criteria were euthanized. The age (in wk) of these mice was taken as the survival time, and these mice were classified as “event occurred” (i.e., dead). KPC mice that had to be euthanized due to nontumor disease-related ethical stop criteria (e.g., bleeding papilloma) were included in Kaplan-Meier analysis as “event not occurred” (i.e., alive) and therefore censored.

Cell lines

Murine 9801 pancreas carcinoma cells, which were derived from the liver metastasis of a KPC mouse, were obtained from Prof. Dr. Jens T. Siveke (West German Cancer Center, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany). 9801 cells were cultured in DMEM (PAN Biotech) containing 10% FBS (PAN Biotech) and nonessential amino acids (100× MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution, 1:100 diluted in media; GIBCO BRL/Thermo Fisher Scientific) and passaged regularly three times per week to maintain confluency below 70%. Human HepaRG cells (HPR101; RRID:CVCL_9720), obtained from Biopredic International and expanded as well as differentiated according to the provider’s instructions, were used as a model for hepatocytes. For TIMP1 treatment of HepaRG cells, differentiation media were removed and RPMI 1640 media (GIBCO BRL/Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 0.1% BSA (sterile filtered; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to differentiated HepaRG cells 24 h before stimulation. For stimulation, media were removed and RPMI 1640 media containing 0.1% BSA with or without 500 ng/ml recombinant human TIMP1 (recombinantly produced as described previously; Schoeps et al., 2021) were added and incubated for 3 h. Media were removed, cells were washed twice with cold PBS (4°C), and 500 µl TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to each well. Cells were lysed by scratching with a cell scraper (Techno Plastic Products), and lysates were transferred into a new vial for RNA isolation. Negative mycoplasma contamination status was routinely verified.

Quantification of TIMP1 in blood plasma

TIMP1 levels in human and murine blood plasma were determined using the human or mouse TIMP1 DuoSet ELISA kit (DY970, DY980; Bio-Techne), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of TIMP1 in human pancreatic tissues by immunohistochemical staining

Construction of a tissue microarray (TMA) from the Toronto cohort was described previously (Connor et al., 2019; Romero et al., 2020). Briefly, H&E sections from research paraffin blocks were reviewed by a pathologist for tumor morphology and content. An optimal area for TMA coring was marked for each block. Tissue cores (1.2 mm) were punched manually and transferred into TMA recipient paraffin blocks. Additional cores of benign pancreatic, renal, pulmonary, and hepatic tissues were included for control and TMA orientation reference purposes. For each case, multiple tumor cores were arrayed (two- to fourfold redundancy) from the paraffin blocks and spread over a total of 13 TMA slides. For TIMP1 staining, 4-µm TMA sections were cut on negatively charged standard slides, and the staining was performed as previously described (Grünwald et al., 2016) using homemade low-temperature citrate, pH 6.0, for antigen retrieval at a 1:350 antibody dilution at 4°C overnight. DAB+ (3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride) was used as a chromogen, which produces a dark brown precipitate readily detected by light microscopy. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides were then digitized for subsequent image analysis using a Leica Aperio AT2 under a 20× objective. TIMP1 staining was quantified using QuPath image analysis software (Bankhead et al., 2017). First, simple tissue detection, TMA disarraying, and superimposing of identifier maps were performed. Then, the analysis was limited to tumor and stroma regions; residual normal pancreatic tissue, blood vessels, islets, and any debris or areas with folding were manually excluded from the analyzed area. Simple cell detection and positive pixel count analysis were performed to yield the number of stained pixels per total pixels. For each slide, the 10 cores with the highest detected staining levels and the 10 cores with the lowest detected staining levels were visually checked to ensure that the staining quantification was accurate. The resultant TIMP1 immunoreactivity values were normalized as the percentage of positive pixels per total pixels (equivalent to area) and averaged across all available cores to obtain per-patient expression levels.

Immunohistochemical staining of TIMP1 in murine pancreatic tissues

Murine pancreatic tissue sections were prepared and stained as described elsewhere (Schoeps et al., 2021). Staining was performed with a primary antibody against murine TIMP1 (20 µg/ml, AF980-SP; R&D Systems), a secondary biotinylated rabbit anti-goat IgG (5570-0009; Sera Care), and phosphatase-labeled streptavidin (5550-0002; Sera Care). The KPL HistoMark RED phosphatase substrate kit (5510-0036; Sera Care) was used for detection following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Targeted RNA expression

For targeted RNA expression analysis, total RNA from cells or human or murine liver tissue using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was isolated as described previously (Grünwald et al., 2016). RT for subsequent analysis of mRNA expression levels was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences and the corresponding probes (Universal ProbeLibrary Set, human; Roche) are listed in Fig. S4 G. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed by using FastStart Universal Probe Master (Rox; Roche) in a StepOnePlus System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 18S ribosomal RNA (Eukaryotic 18S rRNA Endogenous Control Primer; Applied Biosystems) was used as a reference gene for normalization.

Analysis of transcriptomic data from human samples

For transcriptomic analysis of PancTs from human PDAC patients and correlation of TIMP1 mRNA expression in PancTs with overall PDAC patient survival, recently published RNA-seq data (Bailey et al., 2016) were downloaded from the cBioportal database (https://www.cbioportal.org; accession no. paad_qcmg_uq_2016). Median RNA-seq expression data were matched with clinical patient data (Fig. S2 C). Gene expression was compared between male and female patient-derived pancreatic primary tumors with the Mann-Whitney test to calculate P values. To control for multiple testing, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was applied (see Statistical power analyses). Male versus female fold change of gene expression was calculated by division of the medians of each population. For identification of male-specifically up-regulated TDSFs, the subcellular location of all factors that were up-regulated in pancreatic primary tumor tissue from male PDAC patients (Table S2) was examined by using the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org; RRID:SCR_002380). From its subcellular location section, we defined the factors listed as “secreted” or “secretory vesicle” as TDSFs (Fig. 2 A). Overall survival was analyzed between different PC patient subpopulations separated by sex and/or TIMP1 mRNA expression.

For correlation of TIMP1 mRNA expression in PancTs with development of liver metastases after primary tumor resection of PDAC patients, published RNA-seq data (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2017) were downloaded from the FireBrowse database (http://firebrowse.org; accession no. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma PAAD). mRNA-seq data from the Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma PAAD cohort were matched with clinical data (Figs. S1 B and S3 B). For correlation of TIMP1 mRNA expression in colorectal tumors with development of liver metastases after primary tumor resection of CRC patients, published RNA-seq data were downloaded from the FireBrowse database (http://firebrowse.org; accession no. Colorectal adenocarcinoma COADREAD). mRNA-seq data from the Colorectal adenocarcinoma (COADREAD) cohort were matched with clinical data (Fig. S4 C). For correlation of TIMP1 mRNA expression in melanoma tumors with development of liver metastases of SKCM patients, published RNA-seq data were downloaded from the FireBrowse database [http://firebrowse.org; accession no. Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (SKCM)]. mRNA-seq data from the SKCM cohort were matched with clinical data (Fig. S4 D).

Transcriptomic analysis of liver metastases from human PDAC patients was performed with recently published RNA-seq data (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; Gene Expression Omnibus accession no. GSE71729; Moffitt et al., 2015; Fig. S2 A). Because sex information of patient-derived RNA-seq data from liver metastases was missing, sex of each sample was determined by unbiased two-step cluster analysis (Fig. S4 H), based on the assumption that expression from sex chromosomes is not substantially altered in tumors. For this purpose, relative expression of the Y chromosome–encoded gene DDX3Y and relative expression of the X chromosome inactivation factor X inactive specific transcript (XIST) were employed. Two-step cluster analysis for each of the two genes revealed two clusters with high and low expression of DDX3Y or XIST, respectively (Fig. S4 H). Combination of both analyses revealed three homogeneous populations. Population 1 (n = 14) had high expression of DDX3Y and low expression of XIST, which we designated as the male population. Population 2 (n = 9) had low expression of DDX3Y and high expression of XIST, which we designated as female population. Because population 3 (n = 2) showed low expression of both genes, DDX3Y and XIST, we excluded this population from further analyses. Gene expression between the two homogeneous sex populations was compared by Student’s t test to calculate P values. To control for multiple testing, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was applied (see Statistical power analyses). Male versus female fold change of gene expression was calculated by division of the medians of each population. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; version 4.1) was performed as previously described (Reference Gene Set: Human_GOBP_AllPathways_no_GO_iea_August_01_2020_symbol.gmt downloaded from http://download.baderlab.org/EM_Genesets/; Reimand et al., 2019). In brief, genes with significant differential expression (Table S1) in liver tissue of female and male PDAC patients were employed as the gene list, whereas male versus female fold change in gene expression was used as the gene rank in GSEA. Cytoscape (version 3.8) was employed for visualization of GSEA results as an enrichment map (cutoff values: false discovery rate [FDR] q-value = 0.01; normalized enrichment score [NES] >2.0 or <−2.0; number of edges per cluster ≥2).

Analysis of transcriptomic and ATAC-seq data from mouse samples

RNA-seq as well as ATAC-seq data from pancreatic epithelial cells isolated from control, pancreatitis-afflicted (i.e., cerulein-treated), or PDAC-afflicted (i.e., KPflC; Ptf1a-cre;RIK;LSL-KrasG12D;p53fl/+) mice were obtained from a recent publication (Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2021; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; Gene Expression Omnibus accession no. GSE132330). Fold changes, SEs, and adjusted P values of TIMP1 mRNA expression and DNA accessibility of the transcriptional start site (TSS) as well as of a promoter region 1,553 bp upstream of the TSS of the Timp1 gene, respectively, were provided by these publicly available datasets (Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2021).

Statistical power analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in a two-tailed manner using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 software (RRID:SCR_002865; IBM Corp.). Normal distributions of groups were tested by Shapiro-Wilk tests. Correlations between quantitative variables were tested by Spearman correlations due to the absence of normal distribution. If not stated otherwise, two groups were compared using Student’s t test for independent samples in the case of normal distribution (executed by Excel for Mac software version 16.16.23) or a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test for independent variables in the absence of normal distribution. A paired sample t test was employed to compare 5-, 3-, and 1-yr survival rates between male and female populations within a PC patient cohort. Due to the absence of normal distribution, a nonparametric Wilcoxon test was employed to compare expression of a distinct set of pro-metastatic genes between male and female populations within a KPC mouse cohort. A one-sample t test was employed to test whether a normally distributed group of TIMP1-treated HepaRG cells showed SAA1 mRNA expression different from the reference value 1, which was equivalent to the group of untreated HepaRG cells. χ2 test was employed to test differences in the proportion of metastases in distinct tissues between the male and female populations of PC patients. To determine clusters within a given dataset, two-step cluster analysis was performed.

RNA-seq data were analyzed by applying Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) as described elsewhere (Prokopchuk et al., 2021) to control for multiple testing. In brief, genes were ranked based on P values (starting with the smallest) as well as the fold change of expression to subrank genes with the same P values. Benjamini-Hochberg critical values (BHCVs) were calculated for each gene as previously described (Prokopchuk et al., 2021) using an FDR of 0.5 to avoid excessive loss of information (McDonald, 2014). Genes were considered as significantly differentially expressed if the following two criteria were met: (1) P < 0.05 for the respective gene and (2) either P < BHCV for the respective gene or the P value of the respective gene was smaller than the P value of another gene showing P < BHCV (McDonald, 2014).

Time-dependent survival probabilities of KPC mice and PDAC patients as well as time-dependent probabilities of disease recurrence of PDAC patients were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test (Mantel-Cox test) was used to compare statistically significant differences between independent subgroups. Cox regression analysis was employed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) including the corresponding 95.0% confidence interval.

Clustering of PDAC patients based on TIMP1 levels was performed by two-step cluster analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 software (RRID:SCR_002865). For this purpose, TIMP1 levels (quantified as mRNA or protein in PancTs or as protein in blood plasma) were defined as the continuous variable, log likelihood was defined as the distance measured to determine similarity between clusters, and Schwarz’s Bayesian information criterion was employed as the cluster criterion. The number of clusters was defined as “determine automatically,” meaning that the two-step cluster procedure determined the best number of clusters in an unbiased manner. Importantly, clustering of patients by two-step cluster analysis exclusively relied on their respective TIMP1 levels and was totally independent of patient survival, which is in contrast to other cluster methods grouping populations based on an optimized cutoff value with respect to survival, such as maximally selected log-rank statistics (Hothorn and Zeileis, 2008).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow charts of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for PC patients from different cohorts in this study analyzed for sex-dependent metastatic organotropism (related to Fig. 1, C–K), as well as liver metastasis-free survival of female and male PDAC patients, respectively, from the Toronto, Munich, and TCGA cohorts (related to Fig. 1, G–K; and Fig. 7). Fig. S2 presents Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow charts of the inclusion and exclusion criteria of PC patients analyzed for gene expression in the liver (related to Fig. 2, A and B) or pancreas (related to Fig. 3 A), metastasis-promoting gene expression in the liver of healthy female and male mice (related to Fig. 2 C), TIMP1 staining in pancreatic tissue of a cerulein-treated male mouse (related to Fig. 3, C, E, and G), and TIMP1 mRNA expression and accessibility of the TIMP1 gene in exocrine pancreas cells isolated from control, cerulein-treated, or PDAC-afflicted male mice (related to Fig. 3, B–G). Fig. S3 presents the overall survival of female PDAC patients separated by TIMP1 levels (related to Fig. 5) as well as inclusion and exclusion of PDAC patients analyzed for liver metastasis–free survival (related to Fig. 6). Fig. S4 presents liver metastasis–free survival of PDAC patients (male and female combined or subsequently separated by sex) separated by TIMP1 levels (related to Fig. 7), inclusion and exclusion of CRC (related to Fig. 8, A–C) and SKCM (related to Fig. 8, D–F) patients analyzed for liver metastasis–free survival, representative microscopic pictures of pancreatic tissue injury upon cerulein treatment in mice differing in sex and TIMP1 genotype (related to Fig. 3, C, E, and G), representative pictures of hepatic micro- and macrometastases (related to Fig. 2, D–G), sequences of primers employed for targeted mRNA expression analysis (related to Fig. 2 C; Fig. 3, B–E; and Fig. 4, A–E), and the basis of sex determination of the liver transcriptome samples (related to Fig. 2, A and B). Table S1 and Table S2 present sex-dependent expression of genes in liver metastases (related to Fig. 2, A and B) or pancreatic primary tumors (related to Fig. 3 A) of PDAC patients, respectively.

Supplementary Material

presents sex-dependent expression of genes in liver metastases (related to Fig. 2, A and B) of PDAC patients.