Abstract

Feces and serum specimens were collected from three farms in Michigan on which ∼50-lb (8- to 9-week-old) pigs experienced diarrhea just after placement into all-in-all-out finishing barns. The clinical signs (profuse watery diarrhea lasting about 2 weeks and no vomiting) were similar on all farms, and the morbidity rate was high (ranging from 60 to 80%) but without mortality. Eleven diarrheic fecal samples from the farms were tested for group A and C rotaviruses by immune electron microscopy (IEM) and various assays. IEM indicated that the fecal samples reacted only with antiserum against group C rotaviruses, and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis indicated that the samples had characteristic genomic electropherotypes for group C rotavirus. Group C rotavirus was detected by cell culture immunofluorescence (CCIF) tests in nine fecal samples, but no group A rotavirus was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or CCIF. By reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, all 11 fecal samples were positive for group C rotaviruses, with only 2 samples positive for group A rotaviruses. However, a second amplification of RT-PCR products using nested primers detected group A rotaviruses in all samples. Analysis of nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the RT-PCR product (partial-length VP7) of the group C rotavirus showed 87.2 to 91% nucleotide identity and 92.6 to 95.9% amino acid identity among two strong samples from the different farms and the Cowden strain of porcine group C rotavirus. All nine convalescent-phase serum samples tested had neutralizing antibodies to the Cowden strain, and the majority of them had neutralizing antibody against group A rotaviruses (OSU or/and Gottfried strains) by fluorescent focus neutralization tests. Although group C rotaviruses have been reported as a cause of sporadic diarrhea in suckling or weanling pigs, to our knowledge, this is the first report of epidemic diarrhea outbreaks associated with group C rotavirus in older pigs.

Rotaviruses are associated with diarrhea in young animals and humans and are distributed worldwide (6, 12, 19, 22). As members of the family Reoviridae, rotaviruses possess a double capsid layer of concentric icosahedral shells surrounding a genome containing 11 segments of double-stranded (ds) RNA. Rotaviruses are divided into seven serogroups (A through G) on the basis of their distinct antigenicity and dsRNA electropherotypes (2, 19, 22).

Although rotavirus serogroups A, B, C, and E have been reported in swine, only group A rotaviruses are well characterized (8, 19, 22, 24). Group A rotaviruses usually infect nursing and weanling pigs at 1 to 6 weeks of age (7, 8, 24).

Group C rotaviruses were first detected in swine in 1980 (21) and were subsequently identified in humans, ferrets, and cattle (2, 3, 13, 24, 27, 29). Previous studies indicated that group C rotavirus infections are widespread in swine and humans in some parts of the world (1, 2, 4, 10, 15–19, 22, 25), and most adult swine have been found to have antibodies against group C rotaviruses in limited surveys (2, 19, 22, 26). Although group C rotaviruses have been reported as a cause of sporadic diarrhea in nursing or recently weaned pigs (17, 19, 21, 22), to our knowledge, there have been no reports of epidemic diarrhea cases in older pigs. Also, during the last decade, human group C rotaviruses have been associated with several outbreaks of acute diarrhea among adults in Asia, the United States, and Europe (4, 10, 15, 16, 18, 31), suggesting that group C rotaviruses may be emerging enteric pathogens in older humans and animals. In the present study, three farms had diarrhea outbreaks in ∼50-lb feeder pigs when pigs were placed into all-in-all-out finishing barns. We detected and characterized group C rotaviruses from these diarrhea outbreaks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Background of the diarrhea outbreaks.

Three farms (designated I, II, and III) (1,250 to 2,000 multiplier or commercial herds) with a common genetic source had ∼50-lb (8- to 9-week-old) pigs that experienced diarrhea after placement into the all-in-all-out finishing barns (for which management practice allows emptying and cleaning of the building between batches). The two multiplier herds received breeding stock directly from a common nucleus herd and the one commercial herd received its breeding stock from one of the multipliers. Outbreaks of diarrhea occurred on farm I shortly after establishment. Outbreaks also occurred on farms II and III among newly placed pigs originating from farm I. The common clinical signs included profuse and watery diarrhea without vomiting, lasting about 2 weeks. Throughout the outbreaks, pigs grew at a normal rate. On farm I, two of the pigs were necropsied, but no significant lesions were found by histopathological or gross examination. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis of the feces for transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) virus was negative. On farm II, the clinical signs were similar to those on farm I, but the prevalence and severity of diarrhea were lower. Two pigs were necropsied, and their serum tested negative for TGE antibodies. Clinical signs persisted for about 4 to 5 months before disappearing. On farm III, the clinical signs were initially similar to those on farms I and II and gradually decreased in severity and prevalence.

Rotaviruses.

The reference group A rotaviruses were the porcine OSU (P9[P7]G5) and Gottfried (P2B[P6]G4) strains, both propagated in MA104 cells with pancreatin as described previously (23). The reference group C rotaviruses included the porcine Cowden strain propagated in MA104 cells with trypsin as described previously (29). Sequences of HF porcine (accession no. U31748) and Shintoku bovine (accession no. U31750) group C rotaviruses from GenBank were used for comparative genetic analysis.

Samples.

Eleven fecal samples (eight samples, including the 97D strain, from farms I and II and three samples, including the 266 strain, from farm III) were collected from ∼50-lb pigs with diarrhea in all-in-all-out finishing barns. When they were collected, the morbidity rate of Farm III pigs was 100% and that of pigs from the other two farms (I and II) was lower. Negative normal fecal samples (n = 3) from gnotobiotic pigs were also tested as controls for RT-PCR, cell culture immunofluorescence (CCIF) assays, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). Nine convalescent-phase serum samples were collected from farm III 3 months after the diarrhea outbreaks. Acute-phase serum samples were not available.

Virus detection. (i) Immune electron microscopy (IEM).

Twenty-percent virus suspensions were prepared from feces, centrifuged (450 × g for 10 min), and incubated overnight at 4°C with diluted gnotobiotic pig hyperimmune antiserum against group A and group C porcine rotaviruses. After ultracentrifugation (75,000 × g for 1 h), 1 drop of the mixture was negatively stained with an equal volume of 3% potassium phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.0), placed on carbon-coated grids, and examined for virus-antibody aggregates by using an electron microscope as described previously (20).

(ii) Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) of dsRNA.

Viral dsRNA was extracted from fecal samples by previously described procedures (9). Briefly, rotaviruses in feces were clarified by centrifugation (430 × g for 20 min), and sodium dodecyl sulfate and sodium acetate were added to the clarified virus suspensions to concentrations of 1.0%. The virus suspensions were deproteinized with phenol-chloroform, and rotavirus dsRNA was precipitated with ethanol at −20°C for 2 h. The precipitated dsRNA was suspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated sterile water and resolved in 12% polyacrylamide gels by the discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli as described previously (14). The gel was visualized by silver staining (9).

(iii) RT-PCR assay.

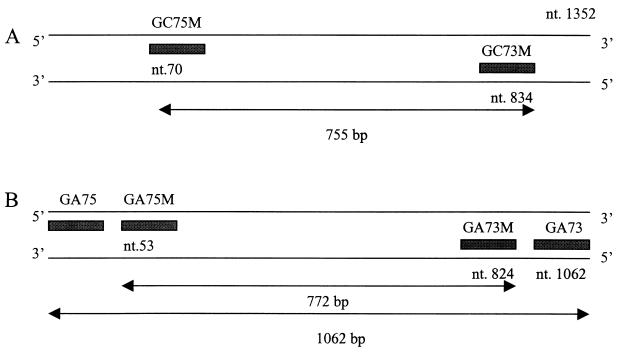

Viral dsRNA was extracted as described above and purified with an RNaid kit (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.), and RT-PCR were performed at 42°C for 90 min for amplification of the first strand of DNA, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 48°C for 1.5 min, and 72°C for 2 min and a final incubation at 72°C for 7 min as described previously (5). Samples were maintained at 4°C until they were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gels. The primer pairs were full-length VP7 genes for group A rotavirus (sense, 5′-GGCCGGATTTAAAAGCGACAATTT-3′; antisense, 5′-AATGCCTGTGAATCGTCCCA-3′) and partial-length (bp 70 to 854) VP7 genes for group C rotavirus (sense, 5′-ACTGTTTGCGTAATTCTCTGC-3′; antisense, 5′-GATATTCTGATAAGTGCCGTG-3′) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Primers for the detection of rotaviruses. (A) Primers for the VP7 gene of group C rotavirus. GC75M and GC73M were the primers for RT-PCR producing 755-bp products. (B) Primers for the VP7 gene of group A rotavirus. GA75 and GA73 were the primers for RT-PCR producing 1,062-bp products; GA75M and GA73M were the nested primers for PCR producing 722-bp products.

(iv) Second-round PCR assay.

The RT-PCR products were diluted with distilled water (1:100), and a second amplification was performed with nested primers (Fig. 1B) (sense, 5′-TAGGTATTGAATATACCACAA-3′; antisense, 5′-GCTACGTTCTCCCTTGGTCCTAA-3′) for 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 52°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final incubation at 72°C for 7 min.

(v) CCIF tests for the detection for group A and C rotavirus antigens.

Confluent monolayers of MA104 cells in 96-well microplates were infected with the fecal samples diluted with minimal essential medium (MEM) (0.2 ml per well) as described previously (26). After incubation at 37°C for 20 h, the infected cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and fixed with 80% acetone. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated gnotobiotic pig hyperimmune antiserum against group A or C porcine rotavirus was added to the fixed cells for 30 min at 37°C. Glycerin mounting medium was added to the wells, and the wells were viewed with an inverted fluorescence microscope. Fluorescence-stained cells were counted, and results were expressed as mean numbers of fluorescence-stained cells per well or fluorescent-focus-forming units (FFU) per milliliter.

Antibody detection by FFN testing.

The neutralizing activity of the serum samples against the Cowden porcine group C rotavirus and OSU and Gottfried porcine group A rotaviruses was determined by a fluorescent focus neutralization (FFN) test as described previously (11). Briefly, the serum samples were serially diluted with MEM from 1:50 to 1:12,500, mixed with viruses containing 104 FFU/ml, and reacted at 37°C for 1 h. The mixtures (100 μl) were inoculated onto monolayers of MA104 cells grown in 96-well plates. After adsorption at 37°C for 1 h, the mixtures were discarded, 200 μl (per well) of MEM containing 0.01% pancreatin was added to the cells, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 20 h. The medium was discarded, and the cells were fixed with acetone and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-OSU and anti-Cowden rotavirus serum. Neutralizing antibody titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that resulted in a 90% or greater more reduction in numbers of FFU. Titers of less than 50 (lowest dilution tested) were considered negative.

Sequencing of the VP7 gene of field group C rotaviruses.

The RT-PCR products (bp 53 to 824) of two fecal samples from different farms were sequenced and analyzed. Amplified cDNA products were treated with shrimp phosphate kinase and exonuclease I at 35°C for 15 min, followed by incubation at 70°C for 15 min. The treated PCR products were sequenced using the Sequenase PCR product sequencing kit (Amersham Life Science). Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence analyses were performed with the DNASTAR program (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.).

RESULTS

Identification of rotaviruses in fecal samples.

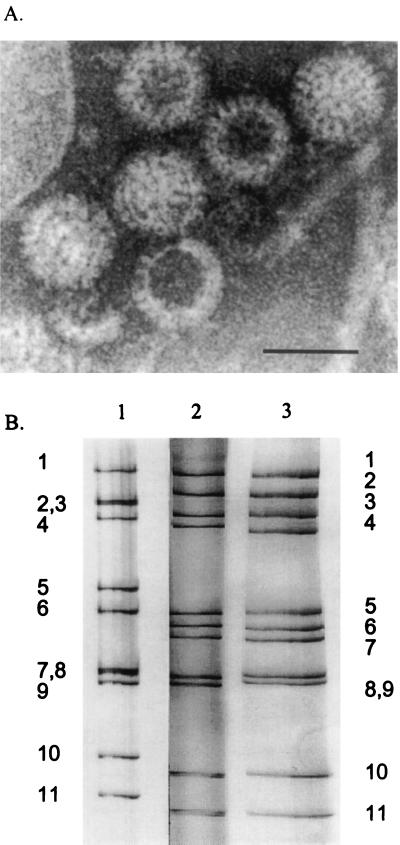

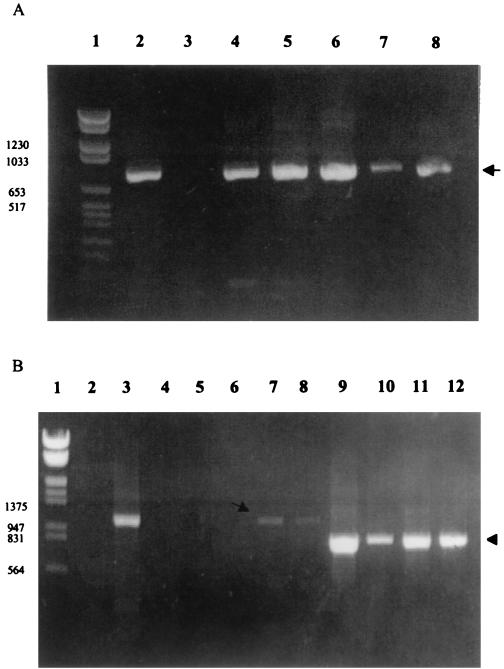

When IEM was conducted with the fecal samples, no samples reacted with antiserum against porcine group A rotavirus, whereas all but two samples (B and I; Table 1) reacted with antiserum against porcine group C rotavirus (Table 1; Fig. 2A). No other viruses were detected in the fecal samples by electron microscopy. The genome profile as determined by PAGE of the two positive fecal samples (C and E) showed 4-3-2-2 dsRNA migration patterns, characteristic of group C rotaviruses (Table 1; Fig. 2B, lane 3). All fecal samples were further screened for group A and C rotaviruses by ELISA and CCIF (Table 1). By group A-specific ELISA and CCIF tests, all the samples were negative, and all but two samples were positive for group C rotavirus by CCIF (Table 1). By RT-PCR using partial-length VP7 group C rotavirus primers, all 11 samples were positive (Table 1; Fig. 1A) and yielded fragments of 755 bp (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 to 8). Only two samples were positive by RT-PCR using the full-length VP7 gene group A rotavirus primers (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 and 8). However, by reamplification of the RT-PCR products (Fig. 1), all the samples were positive for group A (Fig. 3B, lanes 10 to 12). Negative control fecal samples (n = 3) from gnotobiotic pigs did not show any positive reactions by ELISA, CCIF, RT-PCR, and second-round PCR assays.

TABLE 1.

Summary of results of diagnostic tests for the detection of group A and C rotaviruses from the swine field fecal samples

| Field samplea | Results of testing byb:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEM

|

CCIF

|

ELISA

|

PAGE | RT-PCR

|

||||

| Group C | Group A | Group C | Group A | Group A | Group C | Group A | ||

| A | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − (+) |

| B | − | − | − | − | − | nt | + | − (+) |

| C | + | − | + | − | − | Group C | + | − (+) |

| D | + | − | + | − | − | Group C | + | + |

| E | + | − | + | − | − | nt | + | − (+) |

| F | + | − | + | − | − | nt | + | − (+) |

| G | + | − | + | − | − | nt | + | − (+) |

| H | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − (+) |

| I | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| J | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − (+) |

Samples A through H were from farms I and II; samples I and J were from farm III.

− (+), positive only by second-round PCR; nt, not enough sample to test.

FIG. 2.

(A) Immune electron micrograph of group C rotaviruses from a fecal sample collected from farm I or II and aggregated with antiserum to Cowden porcine group C rotavirus (stained with 3% potassium phosphotungstic acid [pH 7.0]). (B) dsRNA electropherotypes of the reference and field rotavirus samples. Lanes: 1, reference group A OSU rotavirus; 2, reference group C Cowden rotavirus; 3, field rotavirus sample (sample C) showing a typical group C rotavirus migration profile (4-3-2-2).

FIG. 3.

(A) The RT-PCR products of reference and field samples detected by using primers specific for the partial VP7 gene of group C rotavirus. Lanes: 1, molecular weight markers; 2, Cowden group C rotavirus; 3, OSU group A rotavirus; 4 to 8, field fecal samples. The arrow indicates the 755-bp product specific for group C rotavirus. (B) RT-PCR and second-round PCR for reference and field samples using primers specific for the VP7 gene of group A rotavirus. Lanes: 1, molecular weight markers; 2, Cowden group C rotavirus; 3, OSU group A rotavirus; 4 to 8, RT-PCR products of field samples. The arrow indicates the 1,062-bp products (lanes 7 and 8) specific for group A rotavirus. Lanes 9 to 12, diluted DNA (1:100) from lanes 3 and lanes 4 to 6 was used for second-round PCR. Lane 9, OSU group A rotavirus; lanes 10 to 12, second-round PCR products of lanes 4 to 6. The arrowhead indicates the 772-bp product. Samples were analyzed using 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Detection of antibodies to group A and C rotaviruses in the serum samples.

Nine convalescent-phase serum samples were tested for neutralizing antibodies to group A and C rotaviruses by the FFN test. All the samples had antibodies to the Cowden group C rotavirus, and 75% (7 of 9) and 22% (2 of 9) of the samples had antibodies to the OSU and Gottfried group A rotaviruses, respectively. The antibody titers to Cowden group C rotavirus were higher (2- to ∼50-fold) than those to OSU (titer, 500 to 2,500) and Gottfried (titer, 100 to 500) group A rotaviruses.

Analysis of the VP7 genes of group C rotaviruses from the field fecal samples.

The partial-length VP7 genes (70 to 834 bp) of two group C rotavirus-positive field samples (D and K) from two different farms (farm I or II and farm III) were analyzed further by sequencing of the RT-PCR products. The samples showed 88.4 to 91.3% nucleotide identity and 93.3 to 93.8% deduced amino acid identity to one another and to the Cowden strain, and 69 to 73% nucleotide identity and 64 to 72% deduced amino acid identity to the porcine group C HF strain and the bovine group C Shintoku strain (Table 2). The GenBank accession numbers of partial-length VP7 genes of 266 and 97D strains were AF093143 and AF093144, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Identity among VP7a genes of field group C rotaviruses from two farms and reference porcine and bovine group C rotaviruses

| Rotavirus or sample | Identity (%)b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample D | Sample K | Cowden | HF | Shintoku | |

| Sample D | 87.2 | 91.0 | 68.8 | 70.0 | |

| Sample K | 92.6 | 90.5 | 71.3 | 70.3 | |

| Cowden | 95.9 | 94.0 | 75 | 76 | |

| HF | 69.0 | 71.9 | 69.9 | 74 | |

| Shintoku | 72.4 | 74.3 | 74.3 | 72.9 | |

Base pairs 70 to 834 of the VP7 genes were sequenced and compared.

DISCUSSION

Based on limited serological surveys, we know that group C rotaviruses are widespread in pigs (2, 19, 22, 26, 28), suggesting that these infections may be endemic, like group A rotaviruses. In a limited survey of U.S. swine herds, Terrett et al. (26) reported that about half of the 3- to 6-week-old pigs tested had group C antibodies and that all adult swine tested were positive for group C antibodies. Interestingly, several recent outbreaks of acute diarrhea associated with group C rotaviruses in adults and children have been observed in Asia (15, 31) and Europe (4, 16), with sporadic cases reported in the United States (10). These observations suggest that group C rotaviruses may also be a cause of diarrhea in older children and adults, and an emerging enteric pathogen for both humans and swine of various ages.

Morin et al. (17) reported an epidemic of group C rotavirus among neonatal pigs at 24 to 48 h after birth in Quebec swine herds, inducing profuse diarrhea and mortality rates of 5 to 10%. In the present study of diarrhea outbreaks on three farms, diarrhea started just after pigs were placed into the all-in-all-out finishing barns, and the morbidity was very high on all three farms (60 to 80%) with no mortality. Group C rotaviruses were detected by IEM in the fecal samples, and their electropherotypes showed 4-3-2-2 dsRNA profiles characteristic of group C rotaviruses by PAGE (2, 19, 22). All the samples contained group C rotaviruses. Small amounts of group A rotaviruses were detected by RT-PCR and second-round PCR and were undetectable by IEM, ELISA, CCIF, and PAGE. Because second-round PCR is an extremely sensitive test, using nested primers, pigs may have been subclinically infected by group A rotaviruses existing on the farms and may have shed extremely small amounts of group A rotaviruses into the feces that were undetectable by other diagnostic assays. Although the role of group A rotaviruses in this diarrhea outbreak is unclear and needs further investigation, it is possible that group A rotaviruses in these outbreaks might have predisposed pigs to group C rotavirus infections by damaging the gut epithelium or aiding in the proliferation and fecal shedding of group C rotaviruses, as suggested in a study of mixed group A and C rotavirus infections in calves (5a). Also, the loss of maternal antibodies to group C rotaviruses may make these older pigs susceptible to group C rotavirus epidemics. All convalescent-phase serum samples from the diarrhea outbreaks tested were group C rotavirus positive, and the majority of them were found by the FFN test to have group A rotavirus antibodies.

For group C rotaviruses, there are at least three G serotypes (porcine Cowden and HF strains and bovine Shintoku strain) based on the VP7 protein, which induces neutralizing antibodies (30). The nucleotide identity and deduced amino acid identity of the VP7 gene between the Cowden and HF porcine and the Shintoku bovine strains ranged from 74 to 75% and 70 to 74%, respectively. The nucleotide identity and deduced amino acid sequence identity of the VP7 genes of group C rotavirus in samples from two different farms were 90 to 91% and 94% with the Cowden strain and only 69 to 73% and 64 to 72% with the HF and Shintoku strains, respectively, indicating that the VP7 genes of group C rotaviruses from these outbreaks were more similar to that of the Cowden strain. Interestingly, these two group C rotaviruses had 88.4% nucleotide identity and 93.3% deduced amino acid identity with each other, indicating that although the group C rotaviruses from these two farms differed, both were similar to the Cowden strain.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of epidemic diarrhea outbreaks associated with group C rotavirus in older pigs. Previous studies have focused on group A rotaviruses, and routine diagnostic methods have been targeted at group A rotaviruses. However, reports of diarrhea outbreaks caused by non-group A rotaviruses are increasing, creating a need to develop and apply sensitive methods to diagnose non-group A rotaviruses in diarrhea outbreaks, such as those reported here.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Salaries and research support were provided by state and federal funds appropriated to the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University. This study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01AI33561).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bohl E H, Saif L J, Theil K W, Agnes A G, Cross R F. Porcine pararotavirus: detection, differentiation from rotavirus, and pathogenesis in gnotobiotic pigs. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:312–319. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.2.312-319.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridger J C. Non-group A rotaviruses. In: Kapikian A Z, editor. Viral infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1994. pp. 369–407. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridger J C, Pedley S, McCrae M A. Group C rotaviruses in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:760–763. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.4.760-763.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caul E O, Ashley C R, Darville J M, Bridger J C. Group C rotavirus associated with fatal enteritis in a family outbreak. J Med Virol. 1990;30:201–205. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890300311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang K-O, Parwani A V, Saif L J. The characterization of VP7 (G type) and VP4 (P type) genes of bovine group A rotaviruses from field samples using RT-PCR and RFLP analysis. Arch Virol. 1996;141:1727–1739. doi: 10.1007/BF01718295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Chang, K.-O., and L. J. Saif. Personal communication.

- 6.Estes M K, Cohen J. Rotavirus gene structure and function. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:410–440. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.410-449.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald G R, Barker T, Welter M W, Welter C J. Diarrhea in young pigs: comparing the incidence of the five most common infectious agents. Vet Med. 1988;83:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu Z F, Hampson D J. Group A rotavirus excretion patterns in naturally infected pigs. Res Vet Sci. 1987;43:297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herring A J, Inglis N F, Ojeh C K, Snodgrass D R, Menzies J D. Rapid diagnosis of rotavirus infection by direct detection of viral nucleic acid in silver-stained polyacrylamide gel. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:473–477. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.3.473-477.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang B M, Dennehy P H, Spangenberger S, Gentsch J R, Glass R I. First detection of Group C rotavirus in fecal specimens of children with diarrhea in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:45–50. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang S Y, Saif L J, Miller K L. Reactivity of VP4-specific monoclonal antibodies to a serotype 4 porcine rotavirus with distinct serotypes of human (symptomatic and asymptomatic) and animal rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2744–2750. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2744-2750.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M. Rotaviruses. In: Field B M, Knipe D M, editors. Virology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 1353–1404. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuzuya M, Fujii R, Hamano M, Yamada M, Shinozaki K, Sasagawa A, Hasegawa S, Kawamoto H, Matsumoto K, Kawamoto A, Itagaki A, Funatsumaru S, Urasawa S. Survey of human group C rotaviruses in Japan during the winter of 1992 to 1993. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:6–10. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.6-10.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto K, Hatano M, Kobayashi K, Hasegawa A, Yamazaki S, Nakata S, Kimura Y. An outbreak of gastroenteritis associated with acute rotaviral infection in schoolchildren. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:611–615. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maunula L, Svensson L, Bonsdorff C-H V. A family outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by group C rotavirus. Arch Virol. 1992;124:269–278. doi: 10.1007/BF01309808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morin M, Magar R, Robinson Y. Porcine group C rotavirus as a cause of neonatal diarrhea in a Quebec swine herd. Can J Vet Res. 1990;54:385–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penaranda M E, Cubitt W D, Sinarachatanant P, Taylor D N, Likanonsakul S, Saif L J, Glass R I. Group C rotavirus infections in patients with diarrhea in Thailand, Nepal, and England. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:392–397. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saif L J. Non-group A rotaviruses. In: Saif L J, Theil K W, editors. Viral diarrhea of man and animals. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saif L J, Bohl E H, Kohler E M, Hughes J H. Immune electron microscopy of transmissible gastroenteritis virus and rotavirus (reovirus-like agent) of swine. Am J Vet Res. 1977;38:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saif L J, Bohl E H, Theil K W, Cross R F, House J A. Rotavirus-like, calicivirus-like, and 23-nm virus-like particles associated with diarrhea in young pigs. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;12:105–111. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.1.105-111.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saif L J, Jiang B. Nongroup A rotaviruses of humans and animals. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;185:330–371. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78256-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saif L J, Rosen B I, Kang S Y, Miller K L. Cell culture propagation of rotaviruses. J Tissue Culture Methods. 1988;11:147–156. doi: 10.1007/BF01404267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saif L J, Rosen B I, Parwani A V. Animal rotaviruses. In: Kapikian A Z, editor. Viral infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1994. pp. 279–367. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigolo De San Juan C, Bellinzoni R C, Mattion N, Torre J L, Scodeller E A. Incidence of group A and atypical rotaviruses in Brazilian pig herds, Res. Vet Sci. 1986;41:270–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terrett L A, Saif L J, Theil K W, Kohler E M. Physicochemical characterization of porcine pararotavirus and detection of virus and viral antibodies using cell culture immunofluorescence. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:268–272. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.2.268-272.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres-Median A. Isolation of an atypical rotavirus causing diarrhea in neonatal ferrets. Lab Anim Sci. 1987;37:167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsunemitsu H, Jiang B, Saif L J. Detection of group C rotavirus antigens and antibodies in animals and humans by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2129–2134. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2129-2134.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsunemitsu H, Saif L J, Jiang B, Shimizu M, Hiro M, Yamaguchi H, Ishiyama T, Hirai T. Isolation, characterization, and serial propagation of a bovine group C rotavirus in a monkey kidney cell line (MA1014) J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2609–2613. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2609-2613.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsunemitsu H, Jiang B, Yamashita Y, Oseto M, Ushijima H, Saif L J. Evidence of serologic diversity within group C rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3009–3012. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.3009-3012.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushijima H, Honma H, Kuhoyama A, Shinozaki T, Fujita Y, Kobayashi M, Ohseto K, Korikawa S, Kitamura T. Detection of group C rotaviruses in Tokyo. J Med Virol. 1989;27:299–303. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890270408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]