Abstract

Objective

We assessed the prevalence of food insecurity (FI) and its associated factors in Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) early during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We performed secondary data analysis of a survey conducted by Facebook and the University of Maryland. We included adults surveyed from April to May 2020. FI was measured by concerns about having enough to eat during the following week. Sociodemographic, mental health, and COVID-19-related variables were collected. We performed generalized Poisson regressions models considering the complex sampling design. We estimated crude and adjusted prevalence ratios with their 95% confidence intervals.

Results

We included 1,324,272 adults; 50.5% were female, 42.9% were under 35 years old, 78.9% lived in a city, and 18.6% had COVID-19 symptoms. The prevalence of food insecurity in LAC was 75.7% (n = 1,016,841), with Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Haiti with 90.8%, 86.7%, and 85.5%, respectively, showing the highest prevalence. Gender, area of residence, presence of COVID-19 symptoms, and fear of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 were associated with a higher prevalence of food insecurity. In contrast, increasing age was associated with a lower prevalence.

Conclusion

The prevalence of food insecurity during the first stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in LAC was high and was associated with sociodemographic and COVID-19-related variables.

Keywords: Food insecurity, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Latin America

Food insecurity; COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Latin America

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread worldwide, causing a social, economic, and health impact [1]. To date, the pandemic has claimed more than 2 million lives worldwide. More than 500 thousand deaths have been reported in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), with Brazil, Mexico and Colombia having the highest number of deaths per day [2, 3]. Prior to the pandemic, these countries already faced challenges, such as low economic growth, informality, poverty, inequality, vulnerability to natural disasters and the effects of climate change, which were exacerbated by the pandemic and further limited their health response capacity [1].

While the full impact of COVID-19 on the global economy is still uncertain, the health crisis has led to an economic slowdown that may increase food insecurity (FI). FI is a complex and dynamic process, it could be defined as uncertain or limited access to enough nutritious food for an active and healthy life [4]. The pandemic generated concern about food availability, especially in vulnerable populations with fewer resources to face unemployment, rising prices, and the low availability of food [5, 6]. Previously, the FI situation in low- and middle-income countries was alarming, with an estimated average of 821 million people undernourished globally between 2016 and 2018 [5,6]. Since the beginning of the pandemic, control measures to limit the spread of the virus included movement restrictions at various international, regional and national levels, causing severe disruption in supply chains and exacerbating the impact of the crisis, and having an important effect on the provision of medical supplies and food [7]. This disruption affected the distribution, availability and access to food and generated an increase in prices and less access to healthy food and state food programs [8, 9].

LAC is the most unequal region in the world, and before the pandemic, it already faced low levels of economic growth and high levels of labour informality. In addition, a fall of 9.1% in the regional gross domestic product (GDP) was estimated in 2020 due to the effects of the pandemic [1]. FI is added to this problem since it is estimated that of the 2 billion people who suffer from FI in the world, 205 million are in LAC [10]. Although Africa concentrates the highest levels of FI worldwide, the increase in LAC has been faster: rising from 22.9% in 2014 to 31.7% in 2019, mainly due to the increase in FI in South America [11].

Identifying modifiable factors associated with FI can serve as a basis for designing strategies that mitigate the consequences of disruptions caused by health crises, such as the pandemic and the consequent FI, and that strengthen regional food systems, making them more sustainable and sustainable. Although several studies have evaluated FI during the pandemic, the majority correspond to high- or low-income countries with socioeconomic and cultural characteristics that do not allow comparisons with our continent [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. In LAC, studies in Brazil, Mexico, and Peru have been published [21, 22, 23]: however, these have been carried out in small samples and did not evaluate the influence of different sociodemographic factors. Therefore, the objective of this research was to know the prevalence and factors associated with FI in LAC countries during the early stage of quarantine due to COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and study area

We carried out a secondary data analysis of a database generated by Facebook (Facebook, Inc) and the University of Maryland. These institutions performed a survey which objective was to collect relevant information related to the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide. The survey was divided into the following modules: sociodemographic characteristics, mental health, COVID-19 symptoms and contact reporting, economic and FI. This survey has been applied since April 2020 and was translated and applied to the participants in the main language of each country [24]. The selection of the surveyed participants was random, within the sample frame of Facebook users according to geographic region and country (each participant included had a weight according to the region and country in which they answered the survey). Daily, a certain number of people (variable according to each day) were invited to answer the survey. In case people declined or skipped the invitation, Facebook invited someone else within the same geographic area and that has not responded to the survey within the last eight weeks. This survey has been used to develop previous studies [25], where more information on the methodology is described.

2.2. Population and area

The survey was applied to adults (aged 18 and over) who used the social network Facebook. LAC adults who responded to the survey were included and totalled 1,440,586 participants. Participants without data related to the variables of interest were excluded, and therefore, 1,324,272 adults from 20 LAC countries were analyzed. The responses to the survey between April 23 and May 23, 2020, were included.

2.3. Variables and procedures

2.3.1. Dependent variable: food insecurity

We evaluated FI using: "How worried are you about having enough to eat in the next week?" which is a question that allows four different answers: very worried, somewhat worried, not too worried, not worried at all. Later we dichotomized this variable as food security when the answer was “not worried at all”, while the other three were considered FI.

2.3.2. Independent variables

2.3.2.1. Sociodemographic variables

We evaluated the following variables: gender (categorized as male, female and non-binary), age (presented as 18 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, and 75 or more), area of residence (rural area, village, town, and city) and if the participant currently worked outside their home (no, yes).

2.3.2.2. Suspicious COVID-19 symptomatology and adherence to community mitigation strategies

We defined suspicious COVID-19 symptoms as the presence of more than two symptoms compatible with an acute condition of COVID-19 [26]. These included: fever, cough, muscle pain, loss of smell, shortness of breath, chest pain, sore throat, eye pain, coryza, tiredness, nausea and headache.

We evaluated adherence to the following community mitigation strategies: physical distancing, hands washing, and mask use. We considered adherence to physical distancing when participants denied any type of direct contact (such as shaking hands, touching, kissing, hugging) for a period longer than one minute in the last 24 h and maintained a distance greater than two meters from any person who does not live in the same household. Likewise, we considered handwashing compliance when participants reported at least one hand wash after leaving home in the last seven days. We defined mask compliance when a mask was used in public (at least at some point) during the last seven days.

2.3.2.3. Mental health

We evaluated depressive symptoms based on one adapted question from the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10): "In the past 7 days, about how often did you feel depressed?", with five categories (all of the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, none of the time) [27]. Then, we dichotomized the variable as absence of depressive symptoms when the answer was "none of the time" and presence of depressive symptoms as any of the four remaining options.

We evaluated anxiety symptoms using one adapted question from the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10): "During the last 7 days, how often did you feel so nervous that nothing could calm you down?" This question allowed five possible answers (all of the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, none of the time) [27]. Then, we dichotomized the variable as the absence of anxious symptoms if they answered, “none of the time” and the presence of anxious symptoms if they answered any of the other four options.

We assessed the fear of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 with the subsequent question: "How worried are you that you or someone in your immediate family might become seriously ill from coronavirus (COVID-19)?". This allowed four responses (very worried, somewhat worried, not too worried, not worried at all). Then, we considered “not worried at all” as the absence of fear of getting seriously ill or that any member of the participant's family will get ill with COVID-19, and the other three options defined the presence of this condition.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We imported our database into the statistical package STATA v14.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA) from a Microsoft Excel 2010 format. For the statistical analyses, we used the svy command to take in count the complex sampling employed by the survey.

Qualitative variables were described with absolute frequencies and proportions considering the survey complex sampling and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). For the bivariate analysis among the variables of interest and the FI, we used the Rao-Scott Chi-square test. The association between independent variables and FI was estimated using a generalized linear model from the Poisson family with a logarithmic link function. Then, we estimated crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) with their respective 95%CI. Using a statistical approach in the adjusted model, we included the variables with a p-value <0.05 in the crude model. Finally, we evaluated collinearity among the variables in the adjusted model conceptually and using the inflation factor of the variance.

2.5. Ethical aspects

All the participants provided informed consent to participate before the start of the survey. The survey and its privacy practices were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland. This institution allowed access through a database use agreement. No personal identifiers were taking into count during the download and analysis of the data.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study sample

We analyzed 1,324,272 LAC adults, of whom 50.5% (n = 723,545) were female, 42.9% (n = 722,070) were under 35 years of age, 78.9% (n = 1,041,369) lived in a city and 18.6% (n = 277,301) had symptoms of COVID-19. Fear of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 was reported by 92.3% (n = 1,238,859), while 46.6% (n = 670,861) had depressive symptoms and 28.6% (n = 379,214) reported working outside from home. FI was described by 75.7% (n = 1,016,841). The adults’ characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample (n = 1,324,272; N = 11,392,965).

| Characteristics | Total |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute frequency of participants surveyed |

Weighted proportion according to each category |

||

| n | % | 95%CI | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 586,275 | 48.1 | 47.7–48.5 |

| Female | 723,545 | 50.5 | 50.1–50.9 |

| Non-binary | 14,452 | 1.4 | 1.2–1.7 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-24 | 313,345 | 18.1 | 17.3–18.8 |

| 25-34 | 408,725 | 24.8 | 24.1–25.5 |

| 35-44 | 280,296 | 18.7 | 18.4–19.0 |

| 45-54 | 177,459 | 18.7 | 18.4–19.1 |

| 55-64 | 103,325 | 11.1 | 10.7–11.5 |

| 65-74 | 35,127 | 7.4 | 6.9–8.0 |

| 75 years or older | 5,995 | 1.2 | 1.1–1.3 |

| Living area | |||

| City | 1,041,369 | 78.9 | 75.8–81.8 |

| Town | 183,959 | 13.8 | 11.5–16.5 |

| Village or rural area | 98,944 | 7.3 | 6.6–8.0 |

| COVID-19 symptomatology | |||

| No | 1,046,971 | 81.4 | 80.5–82.3 |

| Yes | 277,301 | 18.6 | 17.7–19.5 |

| Compliance with the CMS | |||

| No | 736,781 | 54.8 | 53.7–55.9 |

| Yes | 587,491 | 45.2 | 44.1–46.3 |

| Fear of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 | |||

| No | 85,413 | 7.7 | 7.0–8.5 |

| Yes | 1,238,859 | 92.3 | 91.5–93.0 |

| Anxiety symptomatology | |||

| No | 691,608 | 55.3 | 54.7–55.9 |

| Yes | 632,664 | 44.7 | 44.1–45.3 |

| Depressive symptomatology | |||

| No | 653,411 | 53.4 | 52.6–54.1 |

| Yes | 670,861 | 46.6 | 45.9–47.4 |

| Currently works outside the house | |||

| No | 945,058 | 71.4 | 70.2–72.5 |

| Yes | 379,214 | 28.6 | 27.5–29.8 |

| Food insecurity | |||

| No | 307,431 | 24.3 | 23.1–25.4 |

| Yes | 1,016,841 | 75.7 | 74.6–76.9 |

CMS: Community mitigation strategies; CI: Confidence intervals.

3.2. Bivariate analysis according to food insecurity

We found statistically significant differences between FI and the covariates, except for the adherence to community mitigation strategies (p = 0.347). These results are described in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive and bivariate analysis of the study sample characteristics according to food insecurity (n = 1,324,272; N = 11,392,965).

| Characteristics | Food insecurity |

p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

||||||

| Absolute frequency of participants surveyed |

Weighted proportion according to each category |

Absolute frequency of participants surveyed |

Weighted proportion according to each category |

||||

| n | % | 95%CI | n | % | 95%CI | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 442,632 | 74.8 | 73.6–75.9 | 143,643 | 25.2 | 24.1–26.4 | |

| Female | 562,755 | 76.6 | 75.4–77.7 | 160,790 | 23.4 | 22.3–24.6 | |

| Non-binary | 11,454 | 77.1 | 74.0–80.0 | 2,998 | 22.9 | 20.0–26.0 | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 18-24 | 259,885 | 83.7 | 82.8–84.6 | 53,460 | 16.3 | 15.4–17.2 | |

| 25-34 | 329,009 | 82.5 | 81.6–83.3 | 79,716 | 17.5 | 16.7–18.4 | |

| 35-44 | 216,579 | 79.6 | 78.7–80.5 | 63,717 | 20.4 | 19.5–21.3 | |

| 45-54 | 127,797 | 74.3 | 73.4–75.3 | 49,662 | 25.7 | 24.7–26.6 | |

| 55-64 | 64,028 | 64.9 | 63.5–66.2 | 39,297 | 35.1 | 33.8–36.5 | |

| 65-74 | 17,082 | 49.6 | 47.9–51.3 | 18,045 | 50.4 | 48.7–52.1 | |

| 75 years or older | 2,461 | 40.5 | 37.7–43.4 | 3,534 | 59.5 | 56.6–62.3 | |

| Living area | <0.001 | ||||||

| City | 792,561 | 74.9 | 73.8–76.0 | 248,808 | 25.1 | 24.0–26.2 | |

| Town | 146,769 | 79.8 | 78.5–81.1 | 37,190 | 20.2 | 18.9–21.5 | |

| Village or rural area | 77,511 | 76.6 | 75.3–77.7 | 21,433 | 23.4 | 22.3–24.7 | |

| COVID-19 symptomatology | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 786,662 | 74 | 72.7–75.3 | 260,309 | 26 | 24.7–27.3 | |

| Yes | 230,179 | 83.1 | 82.4–83.9 | 47,122 | 16.9 | 16.1–17.6 | |

| Compliance with the three CMS | 0,347 | ||||||

| No | 567,400 | 75.8 | 74.7–76.9 | 169,381 | 24.2 | 23.1–25.3 | |

| Yes | 449,441 | 75.6 | 74.3–76.9 | 138,050 | 24.4 | 23.1–25.7 | |

| Fear of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 39,043 | 44.1 | 42.6–45.7 | 46,370 | 55.9 | 54.3–57.4 | |

| Yes | 977,798 | 78.4 | 77.0–79.7 | 261,061 | 21.6 | 20.3–23.0 | |

| Anxiety symptomatology | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 486,858 | 69.1 | 67.8–70.3 | 204,750 | 30.9 | 29.7–32.2 | |

| Yes | 529,983 | 84 | 82.8–85.1 | 102,681 | 16 | 14.9–17.2 | |

| Depressive symptomatology | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 454,855 | 68.4 | 67.2–69.6 | 198,556 | 31.6 | 30.4–32.8 | |

| Yes | 561,986 | 84.1 | 82.8–85.3 | 108,875 | 15.9 | 14.7–17.2 | |

| Currently works outside the house | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 722,343 | 74.9 | 73.6–76.2 | 222,715 | 25.1 | 23.8–26.4 | |

| Yes | 294,498 | 77.7 | 76.8–78.7 | 84,716 | 22.3 | 21.3–23.2 | |

CMS: Community mitigation strategies; CI: Confidence intervals.

3.3. Prevalence of food insecurity by country

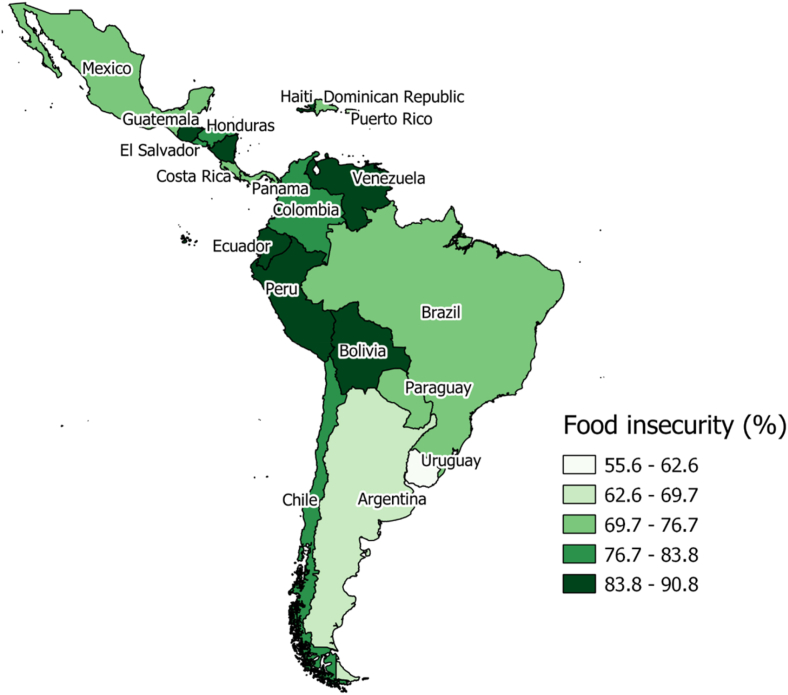

The highest prevalence of FI belonged to Venezuela (90.8%), Nicaragua (86.7%), Haiti (85.5%), Ecuador (85.1%), Bolivia (84.2%), and Peru (83.9%). On the other hand, those with a lower prevalence were Uruguay (55.6%), Puerto Rico (67.2%), and Argentina (68.6%) (Figure 1 and Table 3).

Figure 1.

Prevalence (%) of food insecurity in Latin American and the Caribbean.

Table 3.

Proportion of food insecurity according to countries included in the study sample.

| Countries | Food insecurity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No |

Yes |

|||

| % | 95%CI | % | 95%CI | |

| Argentina | 31.4 | 29.8–33.1 | 68.6 | 66.9–70.2 |

| Bolivia | 15.8 | 14.5–17.2 | 84.2 | 82.8–85.6 |

| Brazil | 27.5 | 26.7–28.6 | 72.5 | 71.4–73.4 |

| Chile | 23.0 | 22.2–23.7 | 77.0 | 76.3–77.8 |

| Colombia | 23.2 | 21.6–24.8 | 76.8 | 75.2–78.4 |

| Costa Rica | 29.6 | 26.6–32.9 | 70.4 | 67.1–73.4 |

| Dominican Republic | 24.9 | 23.0–26.9 | 75.1 | 73.1–77.0 |

| Ecuador | 14.9 | 13.9–16.0 | 85.1 | 84.0–86.1 |

| El Salvador | 16.7 | 15.8–17.7 | 83.3 | 82.3–84.2 |

| Guatemala | 16.2 | 15.4–17.2 | 83.8 | 82.8–84.6 |

| Haiti | 14.5 | 10.2–20.2 | 85.5 | 79.8–89.8 |

| Honduras | 18.4 | 17.3–19.4 | 81.6 | 80.6–82.7 |

| Mexico | 24.1 | 22.3–25.9 | 75.9 | 74.1–77.7 |

| Nicaragua | 13.3 | 12.0–14.8 | 86.7 | 85.2–88.0 |

| Panama | 26.7 | 23.7–30.0 | 73.3 | 70.0–76.3 |

| Paraguay | 26.8 | 25.6–28.1 | 73.2 | 71.9–74.4 |

| Peru | 16.1 | 14.5–17.9 | 83.9 | 82.1–85.5 |

| Puerto Rico, U.S. | 32.8 | 29.2–36.7 | 67.2 | 63.3–70.8 |

| Uruguay | 44.4 | 41.0–47.8 | 55.6 | 52.2–59.0 |

| Venezuela | 9.2 | 8.2–10.3 | 90.8 | 89.7–91.8 |

CI: Confidence intervals.

3.4. Factors associated with food insecurity

In the adjusted regression model, the genders with a higher prevalence of FI were female (aPR = 1.01; 95%CI: 1.01–1.02; p < 0.001) and non-binary (aPR = 1.05; 95%CI: 1.02–1.08; p = 0.006) compared with males. Participants who lived in a rural area or village (aPR = 1.03; 95%CI: 1.02–1.04; p < 0.001) or in a town (aPR = 1.06; 95%CI: 1.04–1.07; p < 0.001) compared to those who lived in a city presented a higher prevalence of FI. Likewise, having COVID-19 symptoms (aPR = 1.06; 95%CI: 1.05–1.07; p < 0.001) and being afraid of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 (aPR = 1.71; 95%CI: 1.67–1.75; p < 0.001) were associated with a greater prevalence of FI. Finally, age from 25 to 34 years old (aPR = 0.99; 95%CI: 0.98–0.99; p < 0.001), 35–44 (aPR = 0.96; 95%CI: 0.96–0.97; p < 0.001), 45–54 (aPR = 0.91; 95%CI: 0.90–0.91; p < 0.001), 55–64 (aPR = 0.80; 95%CI: 0.79–0.81; p < 0.001), 65–74 (aPR = 0.62; 95%CI: 0.60–0.64; p < 0.001) and 75 years and over (aPR = 0.51; 95%CI: 0.48–0.55; p < 0.001) were associated with a minor prevalence of FI in comparison to ages between 18-24 years old (Table 4).

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted generalized linear models of Poisson family with link log to evaluate the factors associated to food insecurity in the study sample.

| Variables | Crude |

Adjusted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cPR | 95%CI | p value | aPR | 95%CI | p value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Female | 1.02 | 1.02–1.03 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.001 |

| Non-binary | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 | 0.062 | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | 0.006 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18-24 | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| 25-34 | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | <0.001 |

| 35-44 | 0.95 | 0.95–0.96 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.96–0.97 | <0.001 |

| 45-54 | 0.89 | 0.88–0.90 | <0.001 | 0.91 | 0.90–0.91 | <0.001 |

| 55-64 | 0.78 | 0.76–0.79 | <0.001 | 0.80 | 0.79–0.81 | <0.001 |

| 65-74 | 0.59 | 0.58–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.62 | 0.60–0.64 | <0.001 |

| 75 years or older | 0.48 | 0.45–0.52 | <0.001 | 0.51 | 0.48–0.55 | <0.001 |

| Living area | ||||||

| City | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Town | 1.07 | 1.05–1.08 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.04–1.07 | <0.001 |

| Village or rural area | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 symptomatology | ||||||

| No | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 1.12 | 1.11–1.14 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.05–1.07 | <0.001 |

| Compliance with the three CMS | ||||||

| No | Reference | - | - | |||

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.353 | Not included | ||

| Fear of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 | ||||||

| No | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 1.78 | 1.73–1.82 | <0.001 | 1.71 | 1.67–1.75 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety symptomatology | ||||||

| No | Reference | - | - | |||

| Yes | 1.22 | 1.21–1.22 | <0.001 | Not included∗ | ||

| Depressive symptomatology | ||||||

| No | Reference | - | - | |||

| Yes | 1.23 | 1.22–1.24 | <0.001 | Not included∗ | ||

| Currently works outside the house | ||||||

| No | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 1.04 | 1.03–1.05 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.297 |

CMS: Community mitigation strategies; CI: Confidence intervals; cPR: Crude prevalence ratio; aPR: Adjusted prevalence ratio.

Not included due to collinearity with fear of becoming seriously ill or that a family member becomes seriously ill from COVID-19.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to identify the factors associated with FI in LAC. We found that the prevalence of FI during the first stage (April–May 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic in LAC was high. Factors such as gender, the area of residence, suspicious COVID-19 symptoms, and the fear of getting seriously ill or that a family member gets seriously ill from COVID-19 were associated with a higher probability of FI. On the contrary, an increase in age was associated with a lower prevalence.

Three out of four people in LAC suffered from FI during the first stage of the pandemic. A study carried out in the United States showed a 13% increase in FI during the first month after the onset of the pandemic, while in Italy, another study showed an increase of 16.2% six months after the beginning of the outbreak [15, 16]. Another study conducted in Australia found a prevalence of FI of 26% at the beginning of the pandemic, while a study in Iran showed a decrease in severe FI by three percentage points over a short period and was associated with purchasing and warehousing of food due to government policies of isolation and closure of some production plants [18]. Studies carried out in Bangladesh, Iran and Jordan showed results similar to those of our study [17, 19, 20]. At the LAC level, previous research corroborates our results, indicating that in the first stage of the pandemic, two favelas located in Brazil [21] and a sector of the population of Peru [23] had FI, while in Mexico [22], one study showed that FI was found at all socioeconomic levels. Our study, however, described a higher prevalence, which may be related to the measurement of FI at the beginning of quarantine in many LAC countries. The application of control measures as movement restrictions to limit the virus spread could have provoked severe disruption in food supply chains in a region with a high prevalence of FI before the pandemic [7]. Similarly, it may be related to aspects described in other countries during the pandemic, such as unemployment, business close, and income reduction in the population [28].

Female and non-binary genders were found to have higher FI compared to males. The 2020 Food Safety and Nutrition Report found a higher prevalence of FI in women than in men [11]. This difference was statistically significant globally in 2019, and especially in LAC, where the same difference was found for all the years of analysis and in which the gender gap in access to food also increased from 2018 to 2019 [1]. A study carried out in the United States agrees with our results, and the authors associate their results with certain traditional roles in which women make home purchases. Likewise, a decrease in income was associated with having suffered from FI before the pandemic [12]. This study also evaluated non-binary gender, showing no significant differences. Furthermore, a study conducted in Canada, found that mothers showed greater concern about limited financial resources due to job losses, reduced working hours and the overload of domestic work due to the closure of schools [29].

Our finding of a higher FI in rural areas may be related to the predominance of informal businesses and situations of extreme poverty in these areas, despite having easier access to self-produced food [23]. On the other hand, it has been reported that during the pandemic in Bangladesh, urban households had a higher prevalence of severe FI (42%) than rural households (15%). It was also noted that urban households were more likely to apply for financial mitigation techniques and access to food than their rural counterparts [19]. Other studies in this country showed that farmers in rural areas had serious difficulties in selling and transporting their products because of higher transport costs and a shortage of workers. Then, despite having higher food prices in the cities, the prices of the products in markets located in rural areas fell by 17%–70%, and farmers experienced large amounts of food waste, causing financial losses in the agricultural-based rural economy [30]. On the other hand, a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) on the impact of COVID-19 on food markets in Bangladesh pointed out that fresh food stores of fruits, fresh vegetables, and meat were closed in urban areas, and average food prices increased by up to 20% [31]. FI evaluates the quantity and quality of food, and then, it is related to food preservation. In this way, in rural areas, FI could be more affected due to the absence of refrigerators. A previous study in Bangladesh found that 41.2% of the population did not have a refrigerator, and this group had a higher probability of FI [28]. Likewise, in 2017, it was described that 49% of the Peruvian population had a refrigerator, but only 7.7% resided in rural areas [32].

`When FI becomes manifest after natural disasters, an association has also been found with the population of rural environments because this population has fewer economic resources and receives little government aid, as well as less possibility of accessing food banks or assistance programs [33, 34, 35]. Most LAC countries have a large workforce in agriculture and livestock, and these sectors have been directly affected by the pandemic [36]. In addition, agricultural workers depend on the sale of their production, and their income is reduced compared to those who work in an urban area since they can adapt to remote work [37].

A gradual decrease in the prevalence of FI was found in relation to increasing age, being lower in participants older than 75 years. A previous study in Australia in the early stage of the pandemic also found that increasing age decreased the probability of FI and that FI decreased by 16% with each decade of difference. The young population was described as being the most affected since they received less income due to the reduction of temporary or part-time jobs [18]. Other studies carried out in the United States, Belgium, Jordan, and Italy reported similar results [13, 15, 16, 20]. It should be noted that given that an older adult in LAC have less use of digital platforms due to fear of complexity or difficulty in using their functions [38, 39, 40], and 42.9% of the people analyzed were under 35 years of age, the findings reported here are not fully representative of people of legal age from LAC.

Having COVID-19 symptoms was another factor associated with FI. The confinement measures taken as a precaution to avoid the spread of the virus in case of having symptoms associated with COVID-19 could explain this finding, with the restrictions in mobility to search for food increasing FI. On the other hand, concern about a relative getting infected was also associated with a higher prevalence of FI. A study conducted in Peru found that respondents with family members suspected of COVID-19 had a higher prevalence of FI [23]. This might be explained in that it is likely that the family member who became ill made the household purchases or generated part of the family income, implying the need to seek new sources of income to cover health and food expenses, as well as the redistribution of household tasks. In the United States, research showed that lower food security decreased the likelihood of requesting vacation days if a family member fell ill with COVID-19 [14].

The countries in which a higher frequency of FI was found have lower per capita incomes. In 2019, the country with the lowest GDP per capita in LAC was Haiti, a nation in which undernourishment is present in 48.2% of the population and has remained constant for the last ten years [41]. Likewise, the political-economic crisis in Venezuela has led to hyperinflation, which began at the end of 2017, with a subsequent increase in FI and undernourishment, the latter having a prevalence of 31.4% [41, 42, 43]. On the contrary, FI is lower in countries such as Uruguay, probably due to their high per capita income, low levels of inequality, indigence, and unemployment [44]. Due to work informality, during quarantine, people are likely to experience greater concern about getting food and therefore greater FI. In Latin America, almost 50% of the people are informal workers, most of whom are located in Central America [45]. In the context of COVID-19, many companies closed, and their workers were laid off. Furthermore, informal workers were affected by the confinement measures, ceasing to receive regular income. However, countries such as Uruguay implemented public policies to reduce informal employment, and its social security reforms focused on income transfers to the most vulnerable sectors with flexible access to net benefits in health and security against unemployment [46].

Some measures that governments have implemented to reduce FI include unemployment benefits, eliminating measures that restrict trade in essential products such as food, emergency food assistance programs, and the massive dissemination of nutritious and healthy diet options and accessible food [47]. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the agricultural sector, and therefore, some public policies should be aimed at training farmers to use low-cost innovations for better production [48]. Other interventions are those based on social responsibility and solidarity of individuals or private companies. There are food banks in many countries. However, they often do not achieve the necessary impact because they are not driven by the government and lack regulations. The use of existing food assistance programs could be used as a platform to monitor FI [49]. These strategies should mainly be focused on the most vulnerable populations such as people living in extreme poverty, older adults, children, pregnant women, indigenous people, immigrants, people at high risk of contagion due to comorbidities, and families with numerous members that reside in rural areas.

Among the study's limitations, it should be pointed out the mode of FI measurement was based mainly on the concern for obtaining food, not evaluating aspects related to the quality of the food. The measurements used to evaluate depressive and anxious symptoms are part of the K10 scale. However, they have not been validated separately. Even so, they provide pertinent information for the study. Likewise, the cross-sectional design does not allow establishing causal relationships between the variables associated with FI. Another limitation is the use of a social network such as Facebook to carry out the survey, being that access to this service by population groups of extreme poverty would be limited. Thus, these groups are not represented in the results of this study. Nonetheless, the analysis of FI in LAC was carried out at the beginning of the pandemic in a large sample at the country level in a social network where four out of every five people in this region belong.

In conclusion, three out of four respondents in LAC reported FI at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences in the frequency of FI in the different countries are consistent with the level of poverty and work informality before the pandemic. We found sociodemographic and COVID-19 related factors associated with FI. Based on our findings, we can elaborate on some recommendations with public health implications. Governments should design policies to protect vulnerable populations such as rural areas habitants against FI, which may include employment programs, economic unemployment benefits, improvement in food distribution chains, and promoting state food programs and nutritional counselling.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Vicente A. Benites-Zapata, Diego Urrunaga-Pastor: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Mayra L. Solorzano-Vargas, Percy Herrera-Añazco, Angela Uyen-Cateriano, Guido Bendezu-Quispe, Carlos J. Toro-Huamanchumo, Adrian V. Hernandez: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University of Maryland for conducting the survey with which this work has been carried out.

References

- 1.United Nations . 2020. Policy Brief: the Impact of COVID-19 on Latin America and the Caribbean; p. 25.https://reliefweb.int/report/world/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-latin-america-and-caribbean-july-2020 (accessed March 14, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . 2021. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed March 14, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Global Tracker . 2021. Latin America and the Caribbean: the Latest Coronavirus Counts, Charts and Maps.https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/regions/latin-america-and-the-caribbean/ (accessed March 15, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman-Jensen A., Rabbitt M.P., Gregory C.A., Singh A. 2019. Household Food Security in the United States in 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations . 2020. Policy Brief: the Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition; p. 23.https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_food_security.pdf (accessed March 15, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández M.V., Osiac L.R., Weisstaub G. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on food security of children and adolescents. Revista Chilena de Pediatria. 2020;91:857–859. doi: 10.32641/rchped.vi91i6.3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury P., Kumar Paul S., Kaisar S., Abdul Moktadir Md. COVID-19 pandemic related supply chain studies: a systematic review. Transport. Res. Part E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2021;148:102271. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2021.102271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Action Against Hunger . 2020. COVID-19 Impact: the Seeds of a Future Hunger Pandemic? p. 28.https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/COVID-19-Field-Insights-Hunger-Pandemic.pdf (accessed March 14, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Social challenge in Times of COVID-1. Vol. 9. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osiac L.R., Rojas D.E., Espinoza P.G., Navarro-Rosenblatt D., Marcela Araya B., Carroza M.B., Cecilia Baginsky G. Let’s avoid food insecurity in covid-19 time in Chile. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2020;47:347–349. [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations . 2020. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niles M.T., Bertmann F., Belarmino E.H., Wentworth T., Biehl E., Neff R. The early food insecurity impacts of covid-19. Nutrients. 2020;12:1–23. doi: 10.3390/nu12072096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandevijvere S., De Ridder K., Drieskens S., Charafeddine R., Berete F., Demarest S. Food insecurity and its association with changes in nutritional habits among adults during the COVID-19 confinement measures in Belgium. Publ. Health Nutr. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020005005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfson J.A., Leung C.W. Food insecurity and COVID-19: disparities in early effects for us adults. Nutrients. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/nu12061648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morales D.X., Morales S.A., Beltran T.F. Racial/ethnic disparities in household food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative study. J. Rac. Ethn. Health Disp. 2020:1. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00892-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dondi A., Candela E., Morigi F., Lenzi J., Pierantoni L., Lanari M. Parents’ perception of food insecurity and of its effects on their children in Italy six months after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Nutrients. 2021;13:1–20. doi: 10.3390/nu13010121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pakravan-Charvadeh M.R., Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F., Gholamrezai S., Vatanparast H., Flora C., Nabavi-Pelesaraei A. The short-term effects of COVID-19 outbreak on dietary diversity and food security status of Iranian households (A case study in Tehran province) J. Clean. Prod. 2021;281 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kent K., Murray S., Penrose B., Auckland S., Visentin D., Godrich S., Lester E. Prevalence and socio-demographic predictors of food insecurity in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 2020;12:1–20. doi: 10.3390/nu12092682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das S., Rasul M.G., Hossain M.S., Khan A.R., Alam M.A., Ahmed T., Clemens J.D. Acute food insecurity and short-term coping strategies of urban and rural households of Bangladesh during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic of 2020: report of a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsahoryi N., Al-Sayyed H., Odeh M., McGrattan A., Hammad F. Effect of Covid-19 on food security: a cross-sectional survey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2020;40:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manfrinato C.V., Marino A., Condé V.F., Franco M.D.C.P., Stedefeldt E., Tomita L.Y. High prevalence of food insecurity, the adverse impact of COVID-19 in Brazilian favela. Publ. Health Nutr. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020005261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaitán-Rossi P., Vilar-Compte M., Teruel G., Pérez-Escamilla R. Food insecurity measurement and prevalence estimates during the COVID-19 pandemic in a repeated cross-sectional survey in Mexico. Publ. Health Nutr. 2021;24:412–421. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020004000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canari-Casano J., Elorreaga O., Cochachin-Henostroza O., Huaman-Gil S., Dolores-Maldonado G., Aquino-Ramirez A., Giribaldi-Sierralta J., Aparco J., Antiporta D., P. M . The Preprint Server for Health Sciences; 2021. Social Predictors of Food Insecurity during the Stay-At-home Order Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru. Results from a Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey, MedRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkay N., Cobb C., Eilat R., Galili T., Haimovich D., LaRocca S., Morris K., Sarig T. Partnership with Facebook. 2020. Weights and methodology brief for the COVID-19 symptom survey by university of Maryland and carnegie mellon university. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urrunaga-Pastor D., Bendezu-Quispe G., Herrera-Añazco P., Uyen-Cateriano A., Toro-Huamanchumo C.J., Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Hernandez A.V., Benites-Zapata V.A. Cross-sectional analysis of COVID-19 vaccine intention, perceptions and hesitancy across Latin America and the Caribbean. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021;41:102059. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO COVID-19 Case Definition. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Surveillance_Case_Definition-2020.2 (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews G., Slade T. Interpreting scores on the kessler psychological distress scale (K10), Australian and New Zealand. J. Publ. Health. 2001;25:494–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kundu S., Banna M.H.A., Sayeed A., Sultana M.S., Brazendale K., Harris J., Mandal M., Jahan I., Abid M.T., Khan M.S.I. Determinants of household food security and dietary diversity during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Publ. Health Nutr. 2021;24:1079–1087. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020005042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll N., Sadowski A., Laila A., Hruska V., Nixon M., Ma D.W.L., Haines J. The impact of covid-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income canadian families with young children. Nutrients. 2020;12:1–14. doi: 10.3390/nu12082352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Impact of Coronavirus on Livelihoods: Rural and Low-Income Population of Bangladesh Covid-19 Series. 2020. p. 33.https://www.lightcastlebd.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Impact-of-Coronavirus-on-Livelihoods-Rural-and-Low-Income-Population-of-Bangladesh.pdf (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 31.FAO Food Market and Food Price Assessment . 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on Dhaka’s Food Market and Food Price Report#6 | Food Security Cluster.https://fscluster.org/bangladesh/document/fao-food-market-and-food-price (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Encuesta Nacional de Hogares . 2017. Características del hogar.https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1539/cap06.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Food Emergencies . 2021. Food Security and Economic Progress in Developing Countries.http://www.fao.org/3/y5117e/y5117e05.htm (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrera-Fontana M.E., Chisaguano A.M., Villagomez V., Pozo L., Villar M., Castro N., Beltran P. Food insecurity and malnutrition in vulnerable households with children under 5 years on the Ecuadorian coast: a post-earthquake analysis. Rural Rem. Health. 2020;20:1–9. doi: 10.22605/RRH5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unidas N. 2020. Employment Situation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Work in Times of Pandemic: the Challenges of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kansiime M.K., Tambo J.A., Mugambi I., Bundi M., Kara A., Owuor C. COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: findings from a rapid assessment. World Dev. 2021;137:105199. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cardozo C., Martin A.E., Saldaño V. Older adults and social networks: analyzing experiences to improve interaction. Informes Científicos Técnicos - UNPA. 2017;9:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saldaño V., Martin A., Gaetan G. 2013. Evaluación del Uso de Redes Sociales en la Tercera Edad. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paterson J.P. Australian health care agreements 2003-2008: a new dawn? Med. J. Aust. 2002;177:313–315. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vásquez G., Urtecho-Osorto Ó.R., Agüero-Flores M., Díaz-Martínez M.J., Paguada R.M., Varela M.A., Landa-Blanco M., Echenique Y. Mental health, confinement, and coronavirus concerns: a qualitative study. Interam. J. Psychol. 2020;54:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regional Overview of Food Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean. FAO, PAHO, WFP and UNICEF; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doocy S., Ververs M.T., Spiegel P., Beyrer C. The food security and nutrition crisis in Venezuela. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;226:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutiérrez S A. The Venezuelan food system: recent trends and perspectives. Anales Venezolanos de Nutrición. 2014;27:153–166. [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Bank . 2019. Uruguay Overview.https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uruguay/overview (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 45.La mitad de los trabajadores de América Latina tienen un empleo informal. 2021. https://www.bancomundial.org/es/news/feature/2014/04/01/informalidad-laboral-america-latina (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 46.OTI . 2014. Reduction of Informal Employment in Uruguay: Policies and Outcomes.https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_245623.pdf (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubio M., Escaroz G., Aulicino C., Paredes F., Guinand M., Vera A., Pemintel D., Chopitea L., Varella S., Pacheco P., Cuevas C., Baracaldo P., Ávila B., Barrientos R., Severino G., Fachrani M., Harracksingh L., Escobar A., Vásquez J., Contreras A., Rivero R., Yarza M., Terán V., Gómez C., González A., Cortés A., Michaud E., Giannareas J., Osorio A., María A., Mez G., Calderón C., Fuletti D. 2021. Social protection Response to COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean.https://www.unicef.org/lac/media/19631/file/Technical_note_1_Social_protection_response_to_COVID-19_in_latin_America_and_the_Caribbean.pdf.pdf (accessed March 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2020. OECD; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribeiro-Silva R. de C., Pereira M., Campello T., Aragão É., Guimarães J.M. de M., Ferreira A.J.F., Barreto M.L., dos Santos S.M.C. Covid-19 pandemic implications for food and nutrition security in Brazil. Ciencia e Saude Coletiva. 2020;25:3421–3430. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232020259.22152020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.