Abstract

Abstract

Tissue fillers injections remain to be one of the most commonly performed cosmetic procedures. The aim of this meta-analysis was to systematize and present available data on the aesthetic outcomes and safety of treating the nasolabial fold area with tissue fillers. We conducted a systematic review of randomized clinical trials that report outcomes concerning treatment of nasolabial fold area with tissue fillers. We searched the MEDLINE/PubMed, ScienceDirect, EMBASE, BIOSIS, SciELO, Scopus, Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials, CNKI and Web of Science databases. Primary outcomes included aesthetic improvement measured using the Wrinkle Severity Rating Scale score and Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale. Secondary outcomes were incidence rates of complications occurring after the procedure. At baseline, the pooled mean WSRS score was 3.23 (95% CI: 3.20–3.26). One month after the procedure, the pooled WSRS score had reached 1.79 (95% CI: 1.74–1.83). After six months it was 2.02 (95% CI: 1.99–2.05) and after 12 months it was 2.46 (95% CI: 2.4–2.52). One month after the procedure, the pooled GAIS score had reached 2.21 (95% CI: 2.14–2.28). After six months, it was 2.32 (95% CI: 2.26–2.37), and after 12 months, it was 1.27 (95% CI: 1.12–1.42). Overall, the pooled incidence of all complications was 0.58 (95% CI: 0.46–0.7). Most common included lumpiness (43%), tenderness (41%), swelling (34%) and bruising (29%). Tissue fillers used for nasolabial fold area treatment allow achieving a satisfying and sustainable improvement. Most common complications include tenderness, lumpiness, swelling, and bruising.

Level of Evidence II

"This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors www.springer.com/00266."

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00266-021-02439-5.

Keywords: Tissue fillers, Dermal fillers, Hyaluronic acid, Nasolabial fold, Meta-analysis

Introduction

During aging, the skin undergoes significant changes, collagen becomes fragmented, and its amount decreases; this hinders the interaction between extracellular matrix and fibroblasts, which leads to further deterioration [1]. Various factors can substantially accelerate this process, including ultraviolet exposure leading to rhytids, lentigines, telangiectasias, mottled pigmentation, coarse texture, laxity, and loss of translucency [2]. There are multiple strategies available to prevent and treat premature aging: cosmetological care, topical agents, invasive procedures (i.e., peelings, wrinkle correction, laser rejuvenation), and systemic agents (antioxidants and hormone replacement therapy) [3]. However, the use of tissue fillers remains one of the most performed non-surgical aesthetic procedures in the world [4]. Tissue fillers are currently being used for facial areas (e.g., folds, lip augmentation, depressed scars, enhancement of facial contours), as well as non-facial areas (neck, décolleté, hands) [5]. Most popular tissue fillers include hyaluronic acid (HA), calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHA), collagen-based products (porcine, bovine, and human-derived), and poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) [6]. Selecting the appropriate filler is crucial in achieving satisfactory, predictable, and sustainable results [7].

The nasolabial fold begins at the junction of the ala nasi, the cheek, and the upper lip and extends in either a straight, convex, or concave shape and ends below and lateral to the corner of the mouth. Its correction was reported to be difficult to achieve by a surgical procedure [8]. Currently, nasolabial fold area wrinkles are most commonly treated with tissue fillers.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is currently a gold-standard approach in making decisions concerning the care of individual patients, also in plastic surgery [9]. Despite the importance of EBM, it is only now being introduced into aesthetic medicine [10]. Therefore, it seems timely to conduct a systematic review with meta-analyses to further evaluate available tissue fillers. This will allow us to determine the appropriate treatment for the nasolabial fold area for each patient in the future and assess its safety.

The aim of this systematic review with meta-analysis was to systematize and present available data on the aesthetic outcomes of treating the nasolabial fold area with tissue fillers and compare the effectiveness and safety of various types of tissue fillers.

Methods

In accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki of 2013, the research was registered at PROSPERO. The assigned unique identifying number was “CRD42020219008”. Ethical approval and patient consent were not required for a systematic review using meta-analysis.

Search Strategy

This study was compliant with the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplement 1) [11]. Our strategy aimed to find relevant randomized clinical trials investigating the treatment of nasolabial fold area with tissue fillers. A wide search using the MEDLINE/PubMed, ScienceDirect, EMBASE, BIOSIS, SciELO, Scopus, Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials, CNKI, and Web of Science databases was performed until March 3, 2019. The PubMed search strategy is presented in Supplement 2. We did not include any date or language filters. The following terms were combined using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” and used to conduct a search: “hyaluronic acid”, “dermal filler”, “Hydroxyapatites”, “CaHA”, “Radiesse”, “Polymethyl Methacrylate”, “Injectable filler”, “injectables”, “Polyalkylimide”, “Poly-L-lactic”, “facial”, “nasolabial”, “cosmetic*”, “naso-labial” and “marionette”. We also performed an extensive reference search in the acquired articles for any additional relevant publications.

Eligibility Assessment

Three independent reviewers performed an eligibility assessment for the relevant full-text articles that were found during the search process. At least two authors assessed each article. We included only prospective randomized clinical trials, reporting data on the treatment of the nasolabial area, which included the Wrinkle Severity Rating Scale (WSRS) score or Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) or complications occurring after the procedure. We excluded studies without a precise description of used dermal filler (for instance, type of the hyaluronic acid used), studies reporting aesthetic improvement results in accordance with other scales than WSRS or GAIS, conference papers, reviews, video articles, case reports, and other studies without relevant data. In case of a lack of agreement between reviewers, a consensus was reached by the whole review team.

Extraction Strategy

The members of the review team extracted data. Articles in a language other than English were translated into English before the data were extracted. When an assessment of WSRS, GAIS, or complications was conducted by patients and a Medical Doctor/Investigator, results derived from a Medical Doctor/Investigator were considered in the presented meta-analysis. If the assessment of WSRS, GAIS, or complications was conducted by a blinded or a not-blinded investigator, the results from a blinded investigator were included in the meta-analysis.

Outcomes of Interest

The following data were extracted from these studies: publication year, study design (double-blinded/single-blinded/non-blinded/single-center/multi-center), location (country), follow-up in months, race, sex (% of women), mean/median age, sample (n), filler type, filler concentration, the amount of filler being injected, location of injection, needle, eventual touch-up injections, the method of injection, GAIS score, WSRS score, overall complications incidence rate and specific complications incidence rate [redness, bruising, swelling, pruritus, skin induration, skin discoloration, pain, nodulus, hematoma, infection, vascular adverse events (AE), migration, numbness and lumpiness]. We have extracted all complications reported in each study. However, if a specific complication was reported in more than one study, a meta-analysis was conducted.

Quality Assessment

The Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB) was used to assess the quality of RCTs included in this meta-analysis. There are seven main domains included in the Cochrane RoB tool: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reports, and other bias. Each domain in each study can be assessed as “high risk of bias”, “low risk of bias”, or “unclear”. Depending on the risk of bias assessment for specific domains overall, each study’s risk of bias was classified as low if all criteria were met (i.e., low risk of bias for each domain) or one criterion was unclear. Alternatively, studies were classified as high risk of bias if one criterion was not met (i.e., high risk of bias for one domain) or two or more criteria were unclear. The risk of bias assessment across studies is presented in Supplementary Material 3.

Statistical Analysis

Calculations were conducted using MetaXL analysis version 2.0 EpiGear Pty Ltd (Wilston, Queensland, Australia) for the multi-categorical pooled prevalence of different types of complications. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.0 by Biostat (Englewood, NJ) was used to analyze the morphometric data. The statistical analysis was based on a random-effects model. In case of lacking standard errors or standard deviations of means, they were estimated using a predictive method proposed by Ma et al. [12].

For heterogeneity assessment, the I^2 statistics were used, and the results were interpreted as follows: 0–40%, “might not be important”; 30–60%, “could indicate moderate heterogeneity”; 50–90%, “may indicate substantial heterogeneity”; and 75–100% “could represent considerable heterogeneity” [13].

The comparison of confidence intervals for any two pooled means indicated differences between the subgroups, and if they overlapped, the difference was considered statistically insignificant.

Results

Acquiring the Studies

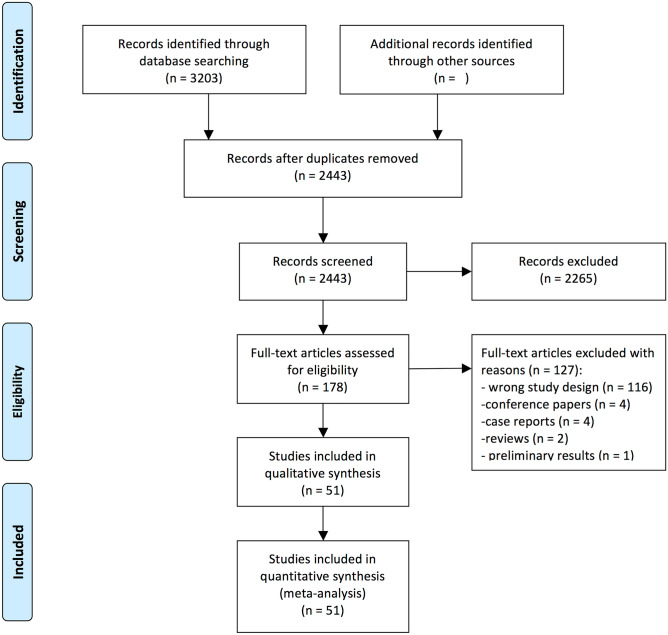

Our search strategy resulted in finding 3203 records. Reference screening of those studies did not yield additional articles that met eligibility criteria. After an eligibility assessment, 51 studies were subjected to extraction and quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis). Fig. 1 presents PRISMA Flow-chart outlining the study inclusion process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart outlining the study inclusion process

Characteristics of the Included Studies

A total of 4097 patients were included in this meta-analysis. Included studies were published between 2004 and 2019 [14–64]. They were conducted in Canada (two studies, 252 participants), China (four studies, 304 participants), France (two studies, 162 participants), Germany (seven studies, 342 participants), Italy (two studies, 139 participants), Norway (one study, 68 participants), South Korea (13 studies, 749 participants), Spain (one study, 60 participants), Sweden (two studies, 110 participants), Switzerland (one study, 126 participants), the UK (two studies, 80 participants), the United Arab Emirates (one study, 40 participants), and the USA (17 studies, 1945 participants). Overall, 35 studies including 3388 patients were conducted in multiple centers, and 16 single-center studies including 709 patients. WSRS scores were reported by 19 studies, including 1155 patients; GAIS scores were reported by 11 studies including 686 patients; and 39 studies including 3281 patients, reported data on complications. All characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. The quality of the analyzed studies, according to the Cochrane RoB tool, is low.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Publication year | Study design | Location | Multicenter versus single center | Follow-up length | Age* | No patients | Filler | Presented outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn | 2012 | Double blind | South Korea | multicenter | 14 weeks | 46.68 | 40 | Mesoglow/IAL System | WSRS/GAIS/Complications |

| Baumann | 2018 | Evaluator blind | USA | multicenter | 48 weeks | 53.7 | 162 | Restylane Defyne/Juvederm Ultra Plus | Complications |

| Beer | 2007 | Evaluator blind | USA | single center | 6 months | 53±12 | 15 | HA/hylan B plus | WSRS/GAIS |

| Brandt | 2010 | Double blind | USA | multicenter | 2 weeks | 53.4±8 | 60 | Perlane—LGP/Perlane –L—LGP with 0.3% lidocaine hydrochloride | Complications |

| Buntrock | 2013 | Double blind | Germany | single center | 48 weeks | 52±5.6 | 20 | CPMHA/biphasic HA filler (NASHA) | WSRS |

| Carruthers | 2005 | Double blind | Canada | multicenter | 12 months | 51,9 (34–83) | 150 | Restylane Perlane/Hylaform | Complications |

| Choi | 2015 | Double blind | South Korea | multicenter | 24 weeks | 52.48 ± 8.23 | 66 | PP-501-A-Lidocaine/Restylane Lidocaine | WSRS/GAIS/Complications |

| Dover | 2009 | Double blind | USA | multicenter | 24 weeks | 54.05 | 283 | NASHA | Complications |

| Fagien | 2018 | Evaluator blind | USA | multicenter | 48 weeks | 53.9±8.22 | 170 | Juvederm Ultra/Restylane Refyne with lidocaine 3% | Complications |

| Fino | 2019 | Double blind | Italy | single center | 6 months | 50.4±8.3 | 65 | Ial System Duo/Belotero Basic/Balance | Complications |

| Galadari | 2015 | Double blind | United Arab Emirates | single center | 12 months | 46 | 40 | polycaprolactone (PCL)/NASHA | WSRS |

| Gold | 2018 | Double blind | USA | multicenter | 24 weeks | 55.4±10.1 | 163 | Revanesse Versa/Restylane | Complications |

| Grimes | 2009 | Double blind | USA | multicenter | 25 weeks | 50 (32–75) | 53 | Juvederm Ultra, Juvederm Ultra Plus, Juvederm 30, Hylaform, Hylaform Plus, Captique | Complications |

| Heden | 2010 | Double blind | Sweden | multicenter | 12 months | 54 | 42 | NASHA | Complications |

| Hong | 2018 | Patient/evaluator-blinded | South Korea | single center | 48 weeks | 48.3±7.36 | 91 | DHF-001, Restylane SubQ | WSRS/ |

| Hu | 2017 | Evaluator blind | China | single center | 12 months | (30–65) | 57 | HA (Nature, Beijing Aimeike Bio-tech Co.), autologous fat injection | WSRS/GAIS/Complications |

| Hyun | 2014 | Evaluator blind | South Korea | multicenter | 24 weeks | 51.9±6.9 | 58 | Restylane, Aesthefill | WSRS/Complications |

| Joo | 2016 | Double blind | South Korea | multicenter | 24 weeks | 47.62±7.64 | 60 | Neuramis, Perlane-L | WSRS/GAIS |

| Kim | 2016 | Evaluator blind | South Korea | multicenter | 24 months | 49.6±11.8 | 13 | HA-G-monophasic, HA-P-biphasic | GAIS/Complications |

| Lee | 2014 | Double blind | South Korea | multicenter | 12 months | 42.2 | 57 | Terafill, Koken | WSRS/GAIS |

| Levy | 2009 | Single blind | Switzerland | multicenter | 53 | 126 | Juvederm Ultra 3, Restylane Perlane | Complications | |

| Lindqvist | 2005 | Single blind | Sweden/Norway | multicenter | 12 months | 49.4 | 68 | Perlane, Zyplast | Complications |

| Lupo | 2007 | Double blind | USA | multicenter | 24 weeks | 49 | 87 | Juvederm Ultra +, Zyplast | WSRS |

| Marmur | 2010 | Single blind | USA | single center | 1 month | 50 | CaHA+lidocaine, CaHA | Complications | |

| Moers-Carpi | 2007 | Evaluator blind | Germany/Spain | multicenter | 12 months | 50.5 (34–67) | 60 | CaHA, NASHA | Complications |

| Monheit | 2018 | Double blind | USA | multicenter | 6 months | 54 (33–83) | 123 | VYC-17.5L (HA+lidocaine) | Complications |

| Monheit | 2010 | Patient/evaluator-blinded | USA | multicenter | 36 weeks | 52.7±9.3 | 140 | DGE, NASHA | Complications |

| Monheit | 2010 | Single blind | USA | single center | 2 weeks | 45 (29–68) | 45 | Prevelle SILK, Captique | Complications |

| Moon | 2014 | Evaluator blind | South Korea | multicenter | 6 months | 47.2 (21–66) | 57 | Porcine collagen, Bovine collagen | WSRS/Complications |

| Narins | 2007 | Evaluator blind | USA | multicenter | 6 months | 56 | 149 | Dermicol-P35, NASHA | Complications |

| Narins | 2010 | Evaluator blind | USA | multicenter | 24 weeks | 52.4 (25.7–75.7) | 118 | CPMHA. bovine collagen | GAIS |

| Nast | 2011 | Double blind | Germany | single center | 4 weeks | 54.8±8.8 | 60 | HA-biphasic, HA-monophasic | WSRS |

| Onesti | 2009 | Double blind | Italy | single center | 6 months | 50.2 | 74 | Captique, Puragen | Complications |

| Pak | 2015 | Double blind | South Korea | multicenter | 6 months | 69 | Neuraminis, Restylane | WSRS/Complications | |

| Park | 2011 | Evaluator blind | South Korea | single center | 4 months | 48.4±5 | 12 | Teosyal, HA (Titan) + Infrared | WSRS/GAIS/Complications |

| Park | 2015 | Double blind | South Korea | multicenter | 6 months | 45.76±7.77 | 98 | PP-501-B, Restylane Perlane PER | WSRS/GAIS/Complications |

| Prager | 2010 | Patient/evaluator-blinded | Germany | single center | 1 month | 45.8 | 20 | Belotero, Restylane | Complications |

| Prager | 2012 | Patient/evaluator-blinded | Germany | single center | 12 months | 45.8 | 20 | Belotero, Restylane | Complications |

| Rhee | 2014 | Evaluator blind | South Korea | multicenter | 6 months | 68 | Elravie, Restylane | WSRS | |

| Rzany | 2011 | Evaluator blind | France/Germany | multicenter | 6 months | 50.6±10.1 | 81 | Emervel Classic, Restylane | Complications |

| Rzany | 2017 | Patient/evaluator-blinded | France/Germany | multicenter | 18 months | 50.8 | 81 | Emervel Classic, Restylane | Complications |

| Schachter | 2016 | Double blind | Canada | multicenter | 1 month | 48.84±9.43 | 102 | CaHA (Radiesse) + lidocaine, CaHA (Radiesse) | Complications |

| Sharma | 2011 | No blinding | UK | single center | 9 months | 17 | Juvederm Ultra 3, Uma Jeunesse | Complications | |

| Sharma | 2018 | Single blind | UK | single center | 9 months | 40.5±11.02 | 73 | Uma Jeunesse Classic, Uma Jeunesse Ultra | Complications |

| Smith | 2007 | Evaluator blind | USA | multicenter | 6 months | 54.7 | 117 | CaHA (Radiesse), human-based collagen (Cosmoplast) | Complications |

| Suh | 2017 | Double blind | South Korea | multicenter | 24 weeks | 46.02±7.21 | 60 | Dermalax implant plus, Restylane Sub-Q | Complications |

| Taylor | 2010 | Patient/evaluator-blinded | USA | multicenter | 24 weeks | 150 | Restylane, Perlane | WSRS/GAIS | |

| Weiss | 2010 | Double blind | USA | multicenter | 2 weeks | 52.1±6.6 | 60 | Restylane + lidocaine, Restylane | Complications |

| Wu | 2016 | Double blind | China | multicenter | 15 months | 44.7 (24–61) | 88 | Restylane, BioHyalux | Complications |

| Wu | 2016 | Double blind | China | multicenter | 6 months | 39 (26–58) | 109 | Restylane, Juvederm Ultra | Complications |

| Zhou | 2016 | Double blind | China | single center | 24 weeks | 47.85 | 50 | Matrifill, Restylane | WSRS |

* Age expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with range or exclusively as mean

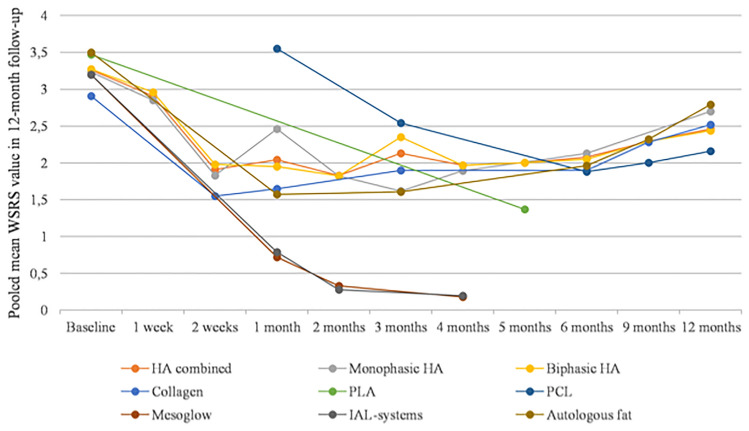

Improvement of the Nasolabial Fold Area—A Meta-Analysis of Reported WSRS Scores

At baseline, the pooled mean WSRS score was 3.23 (95% CI: 3.20–3.26). After the first week since the injection, it was 2.91 (95% CI: 2.82–2.99). At half-month since the initial procedure, the pooled mean WSRS score had dropped to 1.78 (95% CI: 1.72–1.85). One month after the procedure, the pooled WSRS score had reached 1.79 (95% CI: 1.74–1.83). After 2 months, it was 1.64 (95% CI: 1.6–1.68). At 3-, 4-, and 5-month follow-ups, the reported pooled mean WSRS scores were 2.03 (95% CI: 1.97–2.1), 1.68 (1.65–1.72), and 1.59 (95% CI: 1.42–1.76), respectively. A meta-analysis of longer-term follow-up outcomes revealed pooled mean WSRS scores of 2.02 (95% CI: 1.99–2.05), 2.25 (95% CI: 2.18–2.31), and 2.46 (95% CI: 2.4–2.52) for examinations after 6, 9, and 12 months from the filler injection. Pooled mean WSRS scores for specific groups of tissue fillers are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Pooled mean WSRS in 12-month follow-up (pooled means are given as mean with 95% confidence intervals)

| Overall | HA combined | Monophasic HA | Biphasic HA | Collagen | PLA | PCL | Mesoglow | IAL-systems | Autologous fat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3.23 [3.20–3.26] | 3.26 [3.21–3.3] | 3.23 [3.16–3.30] | 3.27 [3.22–3.32] | 2.91 [2.84–2.99] | 3.47 [3.28–3.66] | 3.2 [3.07–3.33] | 3.2 [3.07–3.33] | 3.5 [3.31–3.69] | |

| I2 | 93% | 95% | 94% | 95% | 0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| No of studies | 15 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1st week | 2.91 [2.82–2.99] | 2.91 [2.82–2.99] | 2.85 [2.73–2.98] | 2.96 [2.84–3.08] | ||||||

| I2 | 99% | 99% | 100% | 100% | ||||||

| No of studies | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 weeks | 1.78 [1.72–1.85] | 1.91 [1.83–2] | 1.83 [1.7–1.95] | 1.98 [1.87–2.09] | 1.55 [1.43–1.66] | |||||

| I2 | 89% | 88% | 94% | 76% | NA | |||||

| No of studies | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 month | 1.79 [1.74–1.83] | 2.04 [1.98–2.1] | 2.46 [2.31–2.6] | 1.95 [1.88–2.02] | 1.65 [1.52–1.77] | 3.55 [3.4–3.71] | 0.72 [0.6–0.85] | 0.79 [0.66–0.92] | 1.57 [1.39–1.76] | |

| I2 | 99% | 98% | 0% | 98% | NA | NA | 90% | 74% | NA | |

| No of studies | 7 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 months | 1.64 [1.6–1.68] | 1.83 [1.79–1.87] | 1.82 [1.77–1.87] | 1.82 [1.77–1.87] | 0.33 [0.18–0.48] | 0.28 [0.12–0.44] | ||||

| I2 | 98% | 88% | 91% | 84% | NA | NA | ||||

| No of studies | 8 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 months | 2.03 [1.97–2.1] | 2.13 [2.03–2.22] | 1.62 [1.45–1.79] | 2.35 [2.24–2.46] | 1.9 [1.79–2] | 2.54 [2.33–2.75] | 1.61 [1.4–1.82] | |||

| I2 | 93% | 96% | NA | 93% | 0% | NA | NA | |||

| No of studies | 6 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 months | 1.68 [1.65–1.72] | 1.97 [1.93–2.01] | 1.89 [1.83–1.95] | 1.97 [1.93–2.02] | 0.18 [0.06–0.3] | 0.2 [0.06–0.34] | ||||

| I2 | 99% | 95% | 90% | 96% | NA | NA | ||||

| No of studies | 9 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 months | 1.59 [1.42–1.76] | 2 [1.72–2.28] | 2 [1.72–2.28] | 1.37 [1.16–1.58] | ||||||

| I2 | 92% | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| No of studies | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months | 2.02 [1.99–2.05] | 2.08 [2.04–2.11] | 2.13 [2.08–2.19] | 2.05 [2.01–2.09] | 1.9 [1.83–1.98] | 1.88 [1.68–2.08] | 1.96 [1.67–2.25] | |||

| I2 | 94% | 0% | 94% | 94% | 97% | NA | NA | |||

| No of studies | 15 | 12 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 9 months | 2.25 [2.18–2.31] | 2.29 [2.2–2.38] | 2.29 [2.2–2.38] | 2.28 [2.16–2.39] | 2 [1.83–2.17] | 2.32 [1.95–2.69] | ||||

| I2 | 40% | 0% | 0% | 0% | NA | NA | ||||

| No of studies | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 12 months | 2.46 [2.4–2.52] | 2.46 [2.38–2.54] | 2.7 [2.43–2.97] | 2.44 [2.36–2.52] | 2.52 [2.4–2.63] | 2.16 [1.96–2.36] | 2.79 [2.48–3.1] | |||

| I2 | 84% | 88% | NA | 90% | 0% | NA | NA | |||

| No of studies | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

NA—not applicable

Fig. 2.

Pooled mean WSRS scores in 12-month follow-up

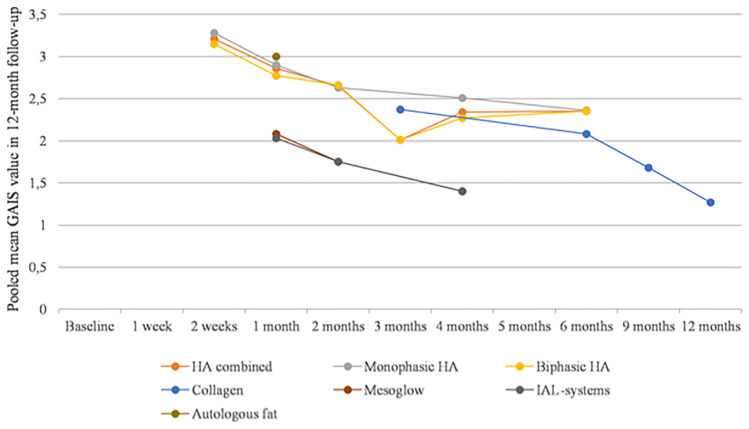

Improvement of the Nasolabial Fold Area: A Meta-Analysis of Reported GAIS Scores

During follow-up examination after a half-month period since the procedure pooled mean GAIS score was 3.21 (95% CI: 3.11–3.32). After the 1 month since the injection, it was 2.21 (95% CI: 2.14–2.28). Two months after the procedure, the pooled mean GAIS score had reached 2.47 (95% CI: 2.43–2.52). At 3, 4, and 5 months since the treatment, the pooled mean GAIS scores were 2.32 (95% CI: 2.21–2.44), 2.24 (95% CI: 2.2–2.29), and 2.78 (95% CI: 2.6–2.96), respectively. At the 6-, 9- and 12-month time points, the pooled mean GAIS scores were 2.32 (95% CI: 2.26–2.37), 1.68 (95% CI: 1.52–1.83), and 1.27 (95% CI: 1.12–1.42), respectively. Pooled mean GAIS scores for specific groups of tissue fillers are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 3.

Table 3.

Pooled mean GAIS scores in 12-month follow-up (pooled means are given as mean with 95% confidence intervals)

| Overall | HA combined | Monophasic HA | Biphasic HA | Collagen | Mesoglow | IAL-systems | Autologous fat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 3.21 [3.11–3.32] | 3.21 [3.11–3.32] | 3.28 [3.13–3.43] | 3.15 [3.01–3.3] | ||||

| I2 | 71% | 71% | 74% | 76% | ||||

| No of studies | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 month | 2.21 [2.14–2.28] | 2.86 [2.55–3.17] | 2.9 [2.53–3.28] | 2.77 [2.21–3.34] | 2.08 [1.97–2.19] | 2.03 [1.93–2.14] | 3 [2.8–3.2] | |

| I2 | 94% | 0% | 0% | NA | 88% | 86% | NA | |

| No of studies | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 months | 2.47 [2.43–2.52] | 2.65 [2.58–2.71] | 2.63 [2.51–2.74] | 2.66 [2.58–2.74] | 1.75 [1.6–1.9] | 1.75 [1.61–1.89] | ||

| I2 | 97% | 74% | 0% | 87% | NA | NA | ||

| No of studies | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 months | 2.32 [2.21–2.44] | 2.01 [1.68–2.33] | 2.01 [1.68–2.33] | 2.37 [2.25–2.5] | ||||

| I2 | 90% | 96% | 96% | 0% | ||||

| No of studies | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 months | 2.24 [2.2–2.29] | 2.34 [2.28–2.4] | 2.51 [2.39–2.63] | 2.27 [2.2–2.35] | 1.4 [1.23–1.57] | 1.4 [1.25–1.56] | ||

| I2 | 98% | 98% | 50% | 98% | NA | NA | ||

| No of studies | 6 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 months | 2.78 [2.6–2.96] | |||||||

| I2 | NA | |||||||

| No of studies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months | 2.32 [2.26–2.37] | 2.35 [2.29–2.42] | 2.36 [2.22–2.5] | 2.35 [2.28–2.43] | 2.08 [1.93–2.24] | |||

| I2 | 93% | 95% | NA | 96% | 0% | |||

| No of studies | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 months | 1.68 [1.52–1.83] | 1.68 [1.52–1.83] | ||||||

| I2 | 0% | 0% | ||||||

| No of studies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 months | 1.27 [1.12–1.42] | 1.27 [1.12–1.42] | ||||||

| I2 | 0% | 0% | ||||||

| No of studies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NA—not applicable

Fig. 3.

Pooled mean GAIS scores in 12-month follow-up

Complications After Treatment of the Nasolabial Fold Area

Overall, the pooled incidence of all complications was 0.58 (95% CI: 0.46–0.7). Among studies reporting the overall complications rate, it was 0.59 (95% CI: 0.46–0.72) for all HA fillers, 0.59 (95% CI: 0.36–0.8) for monophasic HA fillers, 0.6 (95% CI: 0.43–0.76) for biphasic HA fillers, 0.4 (95% CI: 0.12–0.7) for all Collagen fillers, 0.82 (95% CI: 0.69–0.93) for Mesoglow, and 0.88 (95% CI: 0.72–0.99) for IAL-systems. Pooled incidences of specific complications (i.e., redness, bruising, swelling, pruritus, skin induration, tenderness, skin discoloration, pain, nodulus, hematoma, infection, vascular adverse events, migration, numbness, and lumpiness) are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Pooled prevalence of complications given as a proportion of patients in which the complication occurred with 95% confidence interval

| Overall | HA combined | Monophasic HA | Biphasic HA | Collagen | PLA | PCL | Mesoglow | IAL-systems | Autologous fat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All complications | 0.58 [0.46–0.7] | 0.59 [0.46–0.72] | 0.59 [0.36–0.8] | 0.6 [0.43–0.76] | 0.4 [0.12–0.7] | 0.82 [0.69–0.93] | 0.88 [0.72–0.99] | |||

| I2 | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% | 94% | NA | 77% | |||

| No of studies | 19 | 17 | 11 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Redness | 0.26 [0.19–0.33] | 0.23 [0.16–0.3] | 0.26 [0.14–0.39] | 0.2 [0.13–0.29] | 0.25 [0.02–0.53] | 0.5 [0.34–0.66] | 0.43 [0.27–0.58] | 0.29 [0.13–0.47] | ||

| I2 | 97% | 96% | 97% | 96% | 97% | NA | NA | NA | ||

| No of studies | 28 | 22 | 13 | 19 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bruising | 0.29 [0.23–0.35] | 0.28 [0.22–0.36] | 0.29 [0.19–0.4] | 0.28 [0.19–0.38] | 0.16 [0–0.80] | 0.18 [0.07–0.31] | 0.27 [0.18–0.36] | 0.33 [0.16–0.51] | ||

| I2 | 95% | 95% | 93% | 95% | 99% | NA | 0% | NA | ||

| No of studies | 22 | 14 | 11 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Swelling | 0.34 [0.26–0.44] | 0.32 [0.23–0.42] | 0.41 [0.25–0.57] | 0.27 [0.16–0.39] | 0.14 [0–0.38] | 0.67 [0.52–0.81] | 0.65 [0.49–0.79] | 0.4 [0.22–0.58] | ||

| I2 | 98% | 98% | 97% | 98% | 97% | NA | NA | NA | ||

| No of studies | 28 | 22 | 12 | 19 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pruritus | 0.17 [0.11–0.22] | 0.17 [0.11–0.24] | 0.22 [0.13–0.32] | 0.13 [0.06–0.22] | 0.07 [0–0.2] | 0.43 [0.27–0.58] | 0.35 [0.21–0.51] | |||

| I2 | 96% | 96% | 94% | 97% | 92% | NA | NA | |||

| No of studies | 22 | 18 | 11 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Skin induration | 0.11 [0.02–0.27] | 0.14 [0–0.37] | 0.27 [0–0.84] | 0.06 [0–0.17] | 0.07 [0.02–0.15] | |||||

| I2 | 97% | 98% | 98% | 93% | 78% | |||||

| No of studies | 7 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tenderness | 0.41 [0.21–0.63] | 0.39 [0.17–0.64] | 0.66 [0.23–1] | 0.32 [0.1–0.57] | 0.55 [0.39–0.7] | 0.53 [0.37–0.68] | x [x] | |||

| I2 | 98% | 99% | 98% | 98% | NA | NA | x% | |||

| No of studies | 7 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | x |

| Skin discoloration | 0.07 [0.03–0.11] | 0.08 [0.03–0.13] | 0.14 [0.06–0.24] | 0.02 [0–0.05] | 0.01 [0–0.04] | 0.05 [0–0.15] | ||||

| I2 | 92% | 93% | 93% | 80% | 0% | NA | ||||

| No of studies | 12 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain | 0.28 [0.2–0.38] | 0.31 [0.2–0.41] | 0.4 [0.23–0.58] | 0.23 [0.12–0.36] | 0.07 [0–0.19] | 0.57 [0.42–0.73] | 0.75 [0.27–1] | 0.19 [0.06–0.35] | ||

| I2 | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% | 89% | NA | 95% | NA | ||

| No of studies | 27 | 21 | 13 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Nodulus | 0.05 [0.01–0.1] | 0.06 [0.01–0.15] | 0.24 [0.0–0.63] | 0.02 [0.01–0.03] | 0.02 [0.01–0.05] | 0.05 [0–0.15] | 0.11 [0.02–0.25] | |||

| I2 | 96% | 97% | 99% | 35% | 0% | NA | NA | |||

| No of studies | 15 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hematoma | 0.09 [0–0.23] | 0.14 [0–0.23] | 0.14 [0–0.39] | 0.14 [0–0.52] | 0.01 [0–0.02] | |||||

| I2 | 97% | 96% | 95% | 97% | NA | |||||

| No of studies | 6 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 0.01 [0–0.03] | 0.03 [0–0.10] | 0.09 [0.01–0.19] | 0.01 [0–0.02] | ||||||

| I2 | 48% | 1% | 0% | NA | ||||||

| No of studies | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular adverse events | 0.01 [0–0.02] | 0.01 [0–0.02] | 0.01 [0.0–0.02] | 0.01 [0–0.03] | ||||||

| I2 | 0% | 0% | NA | 0% | ||||||

| No of studies | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Migration | 0.08 [0.01–0.17] | 0.08 [0.01–0.17] | ||||||||

| I2 | 69% | 69% | ||||||||

| No of studies | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Numbness | 0.13 [0.01–0.35] | 0.13 [0.01–0.35] | ||||||||

| I2 | 92% | 92% | ||||||||

| No of studies | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lumpiness | 0.43 [0.13–0.76] | 0.43 [0.13–0.76] | 0.34 [0.04–0.72] | 0.82 [0.74–0.89] | ||||||

| I2 | 97% | 97% | 97% | NA | ||||||

| No of studies | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NA—not applicable

Injection Technique

Data concerning the injection techniques among included studies are presented in Supplement 4, including injected volume, HA concentration, depth of injection, needle, eventual touch-up injections and the method of injection.

Discussion

The presented study is one of the first attempts to conduct a comprehensive summary of available randomized clinical trials on tissue fillers, including HA, as well as other fillers, such as collagen, PLA, PCL, Mesoglow, IAL-system, and autologous fat. The focus was on the nasolabial fold, as it is one of the most common locations for tissue fillers injections [65]. Moreover, injecting soft tissue fillers remained one of the most commonly performed cosmetic minimally invasive procedures [66]. Therefore, the relevancy of this meta-analysis cannot be overstated. The search strategy also included marionette folds; however, we did not find available studies to meet our search criteria.

Our results include outcomes on aesthetic improvement measured using WSRS and GAIS scales, as well as a summary of complications following filler injections into the nasolabial fold area. WSRS and GAIS scales were chosen by authors based on the frequent inclusion of them in randomized clinical trials and straightforward interpretation of the results.

We believe that our study is the most comprehensive and current analysis of randomized clinical trials on dermal fillers, conducted according to the EBM principles. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such comprehensive study to gather and summarize the details of injection techniques and maneuvers used in the nasolabial area.

Although the dermal fillers injections are generally considered safe, some adverse events can occur. Clinicians should have comprehensive knowledge of the possible adverse reactions and be experienced in performing injections with correct technique. Due to the high diversity of available products, the injection techniques may vary. Despite that, the Global Aesthetics Consensus Group attempted to list general principles to minimize the risk of complications [67]. For example, the authors stressed that HA can be administered safely through both needle and cannula; however, it is recommended to use cannulas in the areas susceptible to vascular complications. Care should be taken to aspirate before injection to minimize the risk of intravascular injection. The decision on selection of the appropriate depth of injection should depend on the type of filler and instructions given by manufacturer. In general, HA gels should be injected intradermally or subdermally. It is important not to inject too superficially to avoid the formation of lumps [68]. However, in case of less reticulated gels and/or gels with lower concentrations of HA more superficial injections may be favorable [69]. In the vast majority of included studies clinicians used linear threading or multiple punctures technique and injected HA in the mid- to deep-dermis layer with 27- and 30-gauge needles, what seems to agree with the principles mentioned above.

Among studies included in presented meta-analysis injection volume was in general below 2 ml per nasolabial fold. Most commonly concentration of the HA oscillated around 20 mg/ml. In case of injection technique, in studies included, it was performed most commonly using 27G or 30G needle in the mid-dermal region using methods described as linear threading, single puncture, retrograde injection, etc. Unfortunately, definitions of injection methods are imprecise, often mean the same or differ despite the description used. The statistical analysis of aesthetic outcomes or complications based on injection methods described without a prior precise classification seems to be impossible.

According to the meta-analysis of reported WSRS scores, patients receive immediate significant improvement for any type of filler, which is observable already during the first follow-up appointment. This positive outcome was the most observable for HA, collagen, PLA, PCL, and autologous fat implantation. Improvement in the WSRS score reached its peak approximately 3–5 months after the procedure and then gradually subsided.

According to the results of the GAIS scores meta-analysis, patients also receive a significant improvement after administering HA, collagen, PLA, and autologous fat implantation. Pooled GAIS scores were highest during the first follow-up examination and then progressively decreased.

A previous meta-analysis by Huang et al. concerning safety and efficacy of HA for nasolabial folds reported improvement in the WSRS score at the 6-month follow-up of 1.21 [70]. Our results report a difference of 1.15 between baseline and 6-month follow-up for all HA fillers, which is comparable. The small difference might result from the fact that Huang et al. also included non-randomized studies, which might have heightened the results in their review. A meta-analysis by Wang et al. of randomized clinical trials investigating the treatment of nasolabial folds using HA with lidocaine reported HA with lidocaine is more effective, when dealing with pain after the injection. There was no difference in product effectiveness and safety [71]. We have decided not to analyze the role of lidocaine in our meta-analysis. However, we believe that its impact on aesthetic outcomes and overall safeness is minor, which is confirmed by the study mentioned above.

Overall, the pooled incidence of complications was 58%. The highest reported total complications rates were for Mesoglow (82%) and IAL-system (88%). However, it is important to notice that outcomes of treatment with Mesoglow and IAL-system were reported by very few studies. Analysis of incidence among specific complications revealed that most common are mild, transient, and reversible. They include lumpiness (43%), tenderness (41%), swelling (34%), bruising (29%), pain (28%), and redness (26%). More severe complications that could potentially lead to irreversible damage occur very sporadically. The pooled incidence of infections was 1%, and the pooled incidence of vascular adverse events was also 1%. These results are mostly consistent with previously published research. Abduljabbar et al. reported that injection-related side effects are the most common and usually transient, whereas vascular occlusion is the most severe complication, which is associated with hyaluronic acid filler injection [72]. A meta-analysis by Huang et al. presented incidence rates of specific complications after HA treatment for nasolabial folds, which were comparable to reported in this study: for example, redness (28.7%), swelling (37.3%), bruising (24.7%), and pruritus (11.5%) [70]. Meta-analysis concerning vascular events occurring after facial filler injections by Sito et al. reported that vascular adverse events causing injury to ophthalmic and retinal arteries could result in irreversible damage [73]. To avoid these complications, physicians administering facial tissue fillers injections should have appropriate training and extensive knowledge of facial anatomy with a particular focus, but not limited to vascular anatomy. As Dr. Foad Nahai mentioned in his letter, many patients believe that fillers are 100% safe and tend to overlook potential dangers [74]. There are multiple reports describing cases of vascular occlusion after injecting tissue filler in the nasolabial fold-area [75–77]. The risk seems to be higher in patients with history of cosmetic rhinoplasty [78]. Unfortunately, vascular adverse events associated with potential skin necrosis can occur even, if patients are treated by experienced practitioners. Usually vascular occlusion presents with pain and ischemic pallor but often the symptoms may be atypical [79]. According to Lee et al., Doppler ultrasound could be useful for the prevention of vascular complications during filler injections into nasolabial folds [80]. Introducing immediate treatment in this cases is crucial. Most commonly resolution of symptoms is achieved by administering hyaluronidase [81, 82]. In reality, we do not have successful treatments for complications resulting from vascular occlusion with tissue fillers not treated instantaneously, which can cause blindness, skin necrosis, or stroke.

This systematic review with meta-analysis is associated with several limitations. There is a high level of heterogeneity among the included studies, which certainly limits the precision and generalizability of the results. Studies were conducted in multiple countries, and the methodology used differed substantially. We decided to include as much data as possible to create as many comprehensive reports as possible. Also, we included studies using only the two most common aesthetic improvement scales (WSRS and GAIS). Studies using other scoring systems were excluded, which is a potential source of selection bias. We were also unable to assess the injection method and volume or concentration of the filler used, due to the lack of appropriate information in many available studies. The physician/surgeon’s technical proficiency performing the procedures could also have a great impact on the outcomes of the treatment [83]. Additionally, it is important to consider that several fillers (PLA, PCL, Mesoglow, IAL-systems, and Autologous fat) were underrepresented in published studies. Therefore, results concerning these treatments might be less precise.

Researchers investigating this subject in the future should consider conducting studies using aesthetic improvement measurement methods that are validated and widely used. It is also important to introduce definitions of complications and their classification that would be easy to adhere to and be informative when describing outcomes. In certain available studies, over-correction, under-correction, and lack of satisfaction were classified as complications. In our opinion, the definition of complications in aesthetic medicine procedures should be constructed similarly to those used for surgical research. For instance, complications should be defined as an adverse event that occurred within 6 months from the procedure and is not directly associated with the operative technique. This meta-analysis highlights the need for conducting randomized clinical trials for tissue fillers other than HA, which are under-represented in high EBM level studies.

In conclusion, tissue fillers used for nasolabial fold area treatment allow achieving a sustainable (up to 1 year) and satisfying improvement. They are unfortunately associated with complications, most common being tenderness, lumpiness, swelling, and bruising. Most mentioned complications seem to be relatively mild and subside in time.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Human and animal participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tomasz Stefura, Email: tomasz.stefura@gmail.com.

Artur Kacprzyk, Email: artur.kacprzyk@gmail.com.

Jakub Droś, Email: jakub.dros@gmail.com.

Marta Krzysztofik, Email: md.krzysztofik@gmail.com.

Oksana Skomarovska, Email: skomarovska.o@gmail.com.

Marta Fijałkowska, Email: fijalkowska.m@wp.pl.

Mateusz Koziej, Email: mateusz.koziej@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Shin J-W, Kwon S-H, Choi J-Y, et al. Molecular mechanisms of dermal aging and antiaging approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 doi: 10.3390/ijms20092126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han A, Chien AL, Kang S. Photoaging. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganceviciene R, Liakou AI, Theodoridis A, et al. Skin anti-aging strategies. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012;4:308–319. doi: 10.4161/derm.22804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arsiwala SZ. Current trends in facial rejuvenation with fillers. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:125–126. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.167261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vedamurthy M, Vedamurthy A. Dermal fillers: tips to achieve successful outcomes. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2008;1:64–67. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.44161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayan SH, Bassichis BA. Facial dermal fillers: selection of appropriate products and techniques. Aesthetic Surg J. 2008;28:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee W, Hwang S-G, Oh W, et al. Practical guidelines for hyaluronic acid soft-tissue filler use in facial rejuvenation. Dermatologic Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatologic Surg. 2020;46:41–49. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pogrel MA, Shariati S, Schmidt B, et al. The surgical anatomy of the nasolabial fold. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:410–415. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson JA, Schmitz D, Chung KC. How to practice evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:286–294. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181dc54ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Small K, Brandon E, Spinelli HM. Evidence-based medicine in aesthetic medicine and surgery: Reality or fantasy? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:1151–1155. doi: 10.1007/s00266-014-0378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma J, Liu W, Hunter A, Zhang W. Performing meta-analysis with incomplete statistical information in clinical trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn JY, Lee SH, Park KY, et al. Clinical comparison of two hyaluronic acid-derived fillers in the treatment of nasolabial folds: Mesoglow ® and IAL System ®. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumann L, Weiss RA, Grekin S, et al. Comparison of hyaluronic acid gel With (HARDL) and without lidocaine (HAJUP) in the treatment of moderate-to-severe nasolabial folds: a randomized, evaluator-blinded study. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:833–840. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galadari H, van Abel D, Al Nuami K, et al. A randomized, prospective, blinded, split-face, single-center study comparing polycaprolactone to hyaluronic acid for treatment of nasolabial folds. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:27–32. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold MH, Baumann LS, Clark CP, Schlessinger J. A multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, split-face study of the safety and efficacy of a novel hyaluronic acid gel for the correction of nasolabial folds. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:66–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimes PE, Thomas JA, Murphy DK. Safety and effectiveness of hyaluronic acid fillers in skin of color. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedén P, Fagrell D, Jernbeck J, et al. Injection of stabilized hyaluronic acid-based gel of non-animal origin for the correction of nasolabial folds: comparison with and without lidocaine. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:775–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01544.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong JY, Choi EJ, Choi SY, et al. Randomized, patient/evaluator-blinded, intraindividual comparison study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a novel hyaluronic acid dermal filler in the treatment of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:542–548. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu X, Xue Z, Qi H, Chen B. Comparative study of autologous fat vs hyaluronic acid in correction of the nasolabial folds. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:e1–e8. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyun MY, Lee Y, No YA, et al. Efficacy and safety of injection with poly-L-lactic acid compared with hyaluronic acid for correction of nasolabial fold: a randomized, evaluator-blinded, comparative study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:129–135. doi: 10.1111/ced.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joo HJ, Kang H. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lidocaine-containing monophasic hyaluronic acid filler for nasolabial folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:799–808. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000479965.14775.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim BW, Moon IJ, Yun WJ, et al. A randomized, evaluator-blinded, split-face comparison study of the efficacy and safety of a novel mannitol containing monophasic hyaluronic acid dermal filler for the treatment of moderate to severe nasolabial folds. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:297–303. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Choi YS, Kim SM, et al. Efficacy and safety of porcine collagen filler for nasolabial fold correction in Asians: a prospective multicenter, 12 months follow-up study. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:S217–S221. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.S3.S217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beer K. A randomized, evaluator-blinded comparison of efficacy of hyaluronic acid gel and avian-sourced hylan B plus gel for correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatologic Surg. 2007;33:928–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy PM, De Boulle K, Raspaldo H. A split-face comparison of a new hyaluronic acid facial filler containing pre-incorporated lidocaine versus a standard hyaluronic acid facial filler in the treatment of naso-labial folds. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11:169–173. doi: 10.1080/14764170902833142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindqvist C, Tveten S, Bondevik BE, Fagrell D. A randomized, evaluator-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Perlane versus Zyplast in the correction of nasolabial folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:282–289. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000146704.02347.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lupo MP, Smith SR, Thomas JA, et al. Effectiveness of Juvéderm Ultra Plus dermal filler in the treatment of severe nasolabial folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:289–297. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000294968.76862.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marmur E, Green L, Busso M. Controlled, randomized study of pain levels in subjects treated with calcium hydroxylapatite premixed with lidocaine for correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moers-Carpi MM, Tufet JO. Calcium hydroxylapatite versus nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid for the correction of nasolabial folds: a 12-month, multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled, split-face trial. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monheit G, Beer K, Hardas B, et al. Safety and effectiveness of the hyaluronic acid dermal filler VYC-17.5L for nasolabial folds: results of a randomized. Controlled Study Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:670–678. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monheit GD, Baumann LS, Gold MH, et al. Novel hyaluronic acid dermal filler: dermal gel extra physical properties and clinical outcomes. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1833–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monheit GD, Campbell RM, Neugent H, et al. Reduced pain with use of proprietary hyaluronic acid with lidocaine for correction of nasolabial folds: a patient-blinded, prospective, randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:94–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moon S-H, Lee Y-J, Rhie J-W, et al. Comparative study of the effectiveness and safety of porcine and bovine atelocollagen in Asian nasolabial fold correction. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2015;49:147–152. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2014.964725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narins RS, Brandt FS, Lorenc ZP, et al. A randomized, multicenter study of the safety and efficacy of dermicol-P35 and non-animal-stabilized hyaluronic acid gel for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatologic Surg. 2007;33:S213–S221. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandt F, Bank D, Cross SL, Weiss R. A lidocaine-containing formulation of large-gel particle hyaluronic acid alleviates pain. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1876–1885. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narins RS, Coleman W, Donofrio L, et al. Nonanimal sourced hyaluronic acid-based dermal filler using a cohesive polydensified matrix technology is superior to bovine collagen in the correction of moderate to severe nasolabial folds: results from a 6-month, randomized, blinded, controlled, multic. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:730–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01553.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nast A, Reytan N, Hartmann V, et al. Efficacy and durability of two hyaluronic acid-based fillers in the correction of nasolabial folds: Results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind, actively controlled clinical pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:768–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onesti M, Toscani M, Curinga G, et al. Assessment of a new hyaluronic acid filler. double-blind, randomized, comparative study between puragen and captique in the treatment of nasolabial folds. Vivo (Brooklyn) 2009;23:479–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pak C, Park J, Hong J, et al. A phase III, randomized, multi-center, double-masked, matched-pairs, active-controlled trial to compare the efficacy and safety between neuramis deep and restylane in the correction of nasolabial folds. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:721–728. doi: 10.5999/aps.2015.42.6.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park KY, Park MK, Li K, et al. Combined treatment with a nonablative infrared device and hyaluronic acid filler does not have enhanced efficacy in treating nasolabial fold wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1770–1775. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park KY, Ko EJ, Kim BJ, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of PP-501-B in correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:113–120. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prager W, Steinkraus V. A prospective, rater-blind, randomized comparison of the effectiveness and tolerability of Belotero® Basic versus Restylane® for correction of nasolabial folds. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:748–752. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prager W, Wissmueller E, Havermann I, et al. A prospective, split-face, randomized, comparative study of safety and 12-month longevity of three formulations of hyaluronic acid dermal filler for treatment of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1143–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhee DY, Won CH, Chang SE, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new monophasic hyaluronic acid filler in the correction of nasolabial folds: a randomized, evaluator-blinded, split-face study. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25:448–452. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.814756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rzany B, Bayerl C, Bodokh I, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new hyaluronic acid dermal filler in the treatment of moderate nasolabial folds: 6-Month interim results of a randomized, evaluator-blinded, intra-individual comparison study. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2011;13:107–112. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2011.571699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buntrock H, Reuther T, Prager W, Kerscher M. Efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction of a monophasic cohesive polydensified matrix versus a biphasic nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid filler after single injection in nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1097–1105. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rzany B, Bayerl C, Bodokh I, et al. An 18-month follow-up, randomized comparison of effectiveness and safety of two hyaluronic acid fillers for treatment of moderate nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:58–65. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schachter D, Bertucci V, Solish N. Calcium hydroxylapatite with integral lidocaine provides improved pain control for the correction of nasolabial folds. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1005–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma P, Sharma S. Comparative study of a new dermal filler Uma Jeunesse®and Juvéderm®. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:118–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma PP, Sharma DK, Carr A. Comparative study of UMA Jeunesse Classic®and UMA Jeunesse Ultra®. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:1111–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith S, Busso M, McClaren M, Bass LS. A randomized, bilateral, prospective comparison of calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres versus human-based collagen for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:S112–S121. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suh JH, Oh CT, Im SI, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a new monophasic hyaluronic acid filler with lidocaine 0.3% in the correction of nasolabial fold. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:327–332. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor SC, Burgess CM, Callender VD. Efficacy of variable-particle hyaluronic acid dermal fillers in patients with skin of color: a randomized, evaluator-blinded comparative trial. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:741–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiss R, Bank D, Brandt F. Randomized, double-blind, split-face study of small-gel-particle hyaluronic acid with and without lidocaine during correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:750–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Y, Sun N, Xu Y, et al. Clinical comparison between two hyaluronic acid-derived fillers in the treatment of nasolabial folds in Chinese subjects: biohyalux versus restylane. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:145–151. doi: 10.1007/s00403-016-1630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu Y, Xu J, Jia Y, Murphy DK. Safety and effectiveness of hyaluronic acid injectable gel in correcting moderate nasolabial folds in Chinese subjects. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carruthers A, Carey W, De Lorenzi C, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of the efficacy of two hyaluronic acid derivatives, restylane perlane and hylaform, in the treatment of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1591–1598. doi: 10.2310/6350.2005.31246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou S-B, Xie Y, Chiang C-A, et al. A randomized clinical trial of comparing monophasic monodensified and biphasic nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid dermal fillers in treatment of asian nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1061–1068. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi WJ, Han SW, Kim JE, et al. The efficacy and safety of lidocaine-containing hyaluronic acid dermal filler for treatment of nasolabial folds: a multicenter, randomized clinical study. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39:953–962. doi: 10.1007/s00266-015-0571-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dover JS, Rubin MG, Bhatia AC. Review of the efficacy, durability, and safety data of two nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid fillers from a prospective, randomized, comparative, multicenter study. Dermatologic Surg. 2009;35:322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fagien S, Monheit G, Jones D, et al. Hyaluronic acid gel with (HARRL) and without lidocaine (HAJU) for the treatment of moderate-to-severe nasolabial folds: a randomized, evaluator-blinded, phase III study. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:549–556. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fino P, Toscani M, Grippaudo FR, et al. Randomized double-blind controlled study on the safety and efficacy of a novel injectable cross-linked hyaluronic gel for the correction of moderate-to-severe nasolabial wrinkles. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matthews-Brzozowska T, Swatowska A, Tuczyńska M. Nasolabial folds modelling—Sliterature review. J Face Aesthet. 2019;2:46–54. doi: 10.20883/jofa.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2018/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2018.pdf

- 67.Signorini M, Liew S, Sundaram H, et al. Global aesthetics consensus: avoidance and management of complications from hyaluronic acid fillers-evidence- and opinion-based review and consensus recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:961e–971e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peng J-H, Peng PH-L. HA filler injection and skin quality-literature minireview and injection techniques. Indian J Plast Surg Off Publ Assoc Plast Surg India. 2020;53:198–206. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Micheels P, Sarazin D, Besse S, et al. A blanching technique for intradermal injection of the hyaluronic acid Belotero. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:59S–68S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829a02fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang X, Liang Y, Li Q. Safety and efficacy of hyaluronic acid for the correction of nasolabial folds: a meta-analysis. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:592–599. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang C, Luan S, Panayi AC, et al. Effectiveness and safety of hyaluronic acid gel with lidocaine for the treatment of nasolabial folds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:1104–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abduljabbar MH, Basendwh MA. Complications of hyaluronic acid fillers and their managements. J Dermatol Dermato Surg. 2016;20:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jdds.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sito G, Manzoni V, Sommariva R. Vascular complications after facial filler injection: a literature review and meta-analysis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:E65–E72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nahai F. The last word on fillers. Aesthetic Surg J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/asj/sjaa255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McGuire LK, Hale EK, Godwin LS. Post-filler vascular occlusion: a cautionary tale and emphasis for early intervention. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1181–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim J-L, Shin JY, Roh S-G, Lee N-H. Demarcative necrosis along previous laceration line after filler injection. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:e481–e482. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rauso R, Sesenna E, Fragola R, et al. Skin necrosis and vision loss or impairment after facial filler injection. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31:2289–2293. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robati RM, Moeineddin F, Almasi-Nasrabadi M. The risk of skin necrosis following hyaluronic acid filler injection in patients with a history of cosmetic rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Surg J. 2018;38:883–888. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjy005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goodman GJ, Roberts S, Callan P. Experience and management of intravascular injection with facial fillers: results of a multinational survey of experienced injectors. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2016;40:549–555. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0658-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee W, Kim J-S, Moon H-J, Yang E-J. A safe doppler ultrasound-guided method for nasolabial fold correction with hyaluronic acid filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/asj/sjaa153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chauhan A, Singh S. Management of delayed skin necrosis following hyaluronic acid filler injection using pulsed hyaluronidase. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2019;12:183–186. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_129_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sun Z-S, Zhu G-Z, Wang H-B, et al. Clinical outcomes of impending nasal skin necrosis related to nose and nasolabial fold augmentation with hyaluronic acid fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:e434–e441. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rubin MG. Treatment of nasolabial folds with fillers. Aesthetic Surg J. 2004;24:489–493. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.