Abstract

This article explores recent HIV prevention campaigns for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), focusing on how they integrate pleasure and desire in their calls for self-discipline through a continual use of pharmaceuticals. This emerging type of health promotion, here represented by ads promoting the preventive use of pharmaceuticals, no longer simply approaches target groups with demands to abstain from harmful substances or practices and thus control risks, but also includes messages that recognize individuals’ habits, values, and their desires for pleasure. Drawing on Foucault’s work concerning discipline and security, we suggest that a novel, permissive discipline is emerging in contemporary HIV prevention. Further guided by Barthes’s theory of images, we analyse posters used in prevention campaigns, scrutinizing their culture-specific imagery and linguistic messages, i.e. how the words and images interact. We conclude that these campaigns introduce a new temporality of prevention, one centred on pleasure through the pre-emption and planning that PrEP enables.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Security, PrEP, Foucault, Discipline, Pleasure, Sex

Long been the subject of scholarly interest as well as of public debate (Green and Witte 2006; Noar et al. 2009), HIV prevention campaigns have an intricate history that has varied greatly depending on their geographical and historical contexts. Accordingly, such campaigns have employed a wide array of preventive messages, with many promoting a focus on the ‘ABC of HIV’ (abstinence, be faithful, condoms) (Dworkin and Ehrhardt 2007), although some also explicitly articulate desire and sex as prevention keystones (Crimp 1987, 1988, 2004). With the rollout of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), however, campaigns are shifting their focus from condom usage to the use of pharmaceuticals (CDC 2020). The FDA approved Truvada, manufactured by Gilead Sciences, Inc., for prophylactic use against HIV in 2012 (Gilead 2020), and generic PrEP options have since lowered the costs of such programmes. Although PrEP campaigns recognize motivations like pleasure-seeking, such promotion remains an evolving yet under-theorized research domain (Mabire et al. 2019). This article therefore focuses on health campaigns that endeavour to reduce risk by invoking pleasure and desire.

Inspired by Race (2016, 2017), we want to focus on how PrEP emerges as a paradoxical object, what he calls “an enigmatic object: the paradox of the planned slipup” (Race 2016, p. 23). More specifically, Race states that “as a proposition, PrEP asks HIV-negative men not only to acknowledge but also take systematic, prescribed, coordinated, and involved action against a risk that one may not be inclined to acknowledge so readily” (Race 2016, p. 23). As an HIV-preventive technology, PrEP enables HIV-negative men to either identify or disavow themselves as subjects of risk by being in a mode of pre-calculation and intentionality (Race 2016, p. 24) when they seek to prevent HIV by adhering to a drug-based regime. Using Race’s insights as a springboard, we carefully consider how PrEP is promoted in health campaigns aimed at raising awareness of PrEP as an HIV-prevention option. While our analysis follows established theoretical conjectures made by Kane Race, da Silva-Brandao and Ianni, our theoretical perspective on visual advertisements for PrEP usage provides an original contribution to the field. Investigating how PrEP is represented in the visual imagery of health ads, this article focuses on how pleasure, sex, and desire are balanced with messages about planning, calculation, and pre-emption. New qualitative scholarship has documented how PrEP use amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) balances sexual desire and pleasure with planning, discipline, and pre-emption (da Silva-Brandao and Ianni 2020; Grant and Koester 2016; Race 2016). However, less has been said about how PrEP health campaigns balance pre-emption and spontaneous sex, planning and pleasure. In this article, we use the term health promotion to discuss visual advertisements representing PrEP use, thus targeting an interesting blind spot in existing research: since the US launch of PrEP in 2012, several national and regional PrEP campaigns aimed at raising PrEP awareness have also been launched in England, Australia, France, and Canada, among others. Because public health campaigns play an “important role in social governance because they promote and organize knowledge, norms and social practises, they serve as the basis for the development of an expert discourse and they penetrate the individual’s habits of everyday life” (Gagnon et al. 2010, p. 251). As such, the ways in which health campaigns’ visual imagery represents PrEP give scholars an important entry point for pinpointing how risk, desire, and HIV prevention balance pleasure and discipline.

Supplementing Race and inspired by Foucault, we suggest that the discipline at play in recent HIV campaigns is more ‘permissive’ and operates with norms more flexibly than Foucault’s (1977) famous study of discipline in prisons, barracks, and factories anticipated. When Foucault (1990) spoke of discipline in relation to sexuality, he described neither a simple capture of the sexual subject, nor a suppression of sex under a ‘Victorian’ morality. Rather, the 20th-century advent of our modern sexuality discourse spurred endless medical, juridical, and psychological deliberations on sex, as well as the invention of numerous distinctions between sexual normality and abnormalities. Meanwhile, the modern welfare state intensified its concerns for the health and vitality of the population as a totality. A key problem became how to align health objectives at the population level (e.g., epidemic prevention) with the behaviours of groups, families, and individuals. Health campaigns like those examined here ostensibly serve to align a population’s protection with the self-conduct of the individual body. Foucault argued that ‘sexuality’ had become the register through which statistical public health concerns would intersect with the minuscule health guidance given to families and individuals. Importantly, the modern discourse on sexuality has prompted calls for sex liberation, the dissolution of gender binaries, and the promise that self-liberation and self-fulfilment arise from freeing one’s sexuality. Contemporary health promotion has begun accommodating such calls for more tolerant and permissive attitudes to sexuality and sexual conduct. Indeed, the PrEP campaigns we examine can hardly be termed ‘disciplinary’ if the term denotes a univocal constraint or repression of individuals’ sexuality. These campaigns seek not to judge human behaviour against pre-established, rigid norms, but to encourage the target group to take up preventive practices that align with their own aspirations and desires.

Discipline, security, and a new permissiveness

We base our study on the premise that contemporary HIV prevention aims to produce subjects who minimize risks by practising a form of disciplinary, yet pleasure-seeking self-conduct. As such, we contribute to the broader “history of the different modes by which, in our culture, human beings are made subjects” (Foucault 2000, p. 5). Early in his lecture series Security, Territory, Population (2007a, pp. 5–24), Foucault elucidated the contradictory ideals pervading contemporary health promotion by analysing three essential modes of modern governance: law, discipline, and security. Schematically, Foucault said that “sovereignty is exercised within the borders of a territory, discipline is exercised on the bodies of individuals, and security is exercised over a whole population” (2007a, p. 11).

This is the context in which we focus on discipline and security, their being of most immediate relevance to contemporary health promotion. According to Foucault, discipline aspires to prevent unwanted actions from happening by correcting and moulding the body toward a state of perfection (2007a, p. 21). The means of discipline include “a series of adjacent, detective, medical, and psychological techniques … which fall within the domain of surveillance, diagnosis, and the possible transformation of individuals” (Foucault 2007a, p. 5). The disciplinary techniques of examination, comparison, surveillance, and corrective sanctions all mould individuals in accordance with norms. Foucault emphasized how the disciplining of bodies depended on the control of time—its minute division at the workplace, the asylum, schools, and barracks. Thus, continuous training and the differentiation of time into intervals with designated tasks characterize the ‘temporality’ of discipline. This continuity of discipline was intended to prevent the discontinuity of spontaneous, irregular, and inutile actions (2015, pp. 70–72). Recent preventive health campaigns, we suggest, echo this disciplining of the body through a careful preventive regimentation of individuals’ time.

Security breaks with discipline insofar as it is not concerned with correcting the body but rather centres on facilitating those inherent processes of human life—the circulation of men and things—uncontainable within disciplinary institutions. Security diverges from the disciplinary aspiration for perfection, instead taking reality as given and considering how to manage processes that operate in this reality. Rather than seeking to eliminate abnormal behaviour, security concerns levels of acceptability in regard to crimes or diseases, “while knowing that they will never be completely suppressed” (2007a, p. 19). Security calculations insert crime, grain production, or the spread of disease into a series of events so that one can predict probabilities and estimate potential risks. Hence, security “establishes an average considered as optimal on the one hand, and, on the other, a bandwidth of the acceptable that must not be exceeded” (Foucault 2007a, p. 6). Offering an inherently predictive worldview to governmental practices, the securitization of epidemics entails estimating the rate of infection while weighing the costs of intervening against the consequences of letting the disease circulate. The temporality of security seeks to anticipate and plan for future events, with reality being a series of events occurring within predictable intervals.

In health prevention, a disciplinary strategy would seek to eradicate an infectious disease by employing techniques like curfew, quarantine, and isolation, while security calculations would seek to determine how to maintain acceptable infection levels. Indeed, Lakoff (2015) suggests that Foucault’s notion of security is useful for analysing devices intended to mitigate unprecedented, infectious diseases that cannot be controlled but only anticipated and prepared for. Lakoff contrasts discipline with the securitization of epidemics: “If disciplinary mechanisms seek to restrict the circulation of disease, isolating the sick from the healthy—as in quarantine—security mechanisms allow disease to circulate but minimize its damage through collective interventions such as mass vaccination” (2015, p. 42). To securitize epidemics, one must have statistical knowledge of infection disease patterns to prepare for them, slow their spread, and minimize their damages.

In Foucault’s own analysis, he describes how answers to thorny governmental problems depend greatly on whether discipline or security is the framework. A brief look at recent governmental responses to the COVID-19 pandemic can serve to illustrate the competing solutions these two rationalities offer. One set of official pandemic responses can be termed disciplinary. These might include physical distancing campaigns, quarantine restrictions, or, the closure of educational institutions. Another set resonates more strongly with the rationality of security. These could include calculations regarding acceptable levels of incidence, death rates, and public-health-sector expenses.

Analytically, one must keep three points in mind when drawing upon Foucault’s concepts. First, the use of concepts like discipline and security is not intended to predetermine the field of possible empirical observations, but, as Foucault expresses (2007b, p. 60), only provides “an analytical grid”. For this reason an analysis must examine the specific historical context, often by developing and embedding the concept in the specific material under scrutiny. Second, one should refrain from thinking of discipline or security as something stable with permanently fixed contours, but rather see it as evolving over time in a dynamic interplay. This is why Foucault emphasized the mutual interplay of governmental modalities, which causes transformations in “the system of correlation between juridical-legal mechanisms, disciplinary mechanisms, and mechanisms of security” (2007a, p. 22). One should thus be prepared for discipline to transform over time and in its interplay with other governance modes, rather than strive to identify phenomena corresponding to Foucault’s original descriptions. Indeed, Foucault’s concepts “require a careful disinterring”; that is, they must be disembedded from their context in order to become operative in others (Koopman and Matza 2013, p. 825).

Initially, we note that the PrEP campaigns studied display a novel, more permissive discipline that eschews the classical notion of normalization. This discipline is prepared to discover, recognize, and operate on a multiplicity of life forms, including those considered as abnormal and thus as posing a risk or behaving ‘irrationally’ from a health perspective. This inclusiveness resonates with recent shifts in health promotion towards integrating the target groups’ values, habits, and desires, as noted by Karlsen and Villadsen (2016). Rather than prohibiting unhealthy and pleasure-seeking practices, these campaigns strive to align the subjects’ desires for pleasure with a rational, medically informed precaution, thus seeking, for example, not to condemn illegal drug use but to limits its occurrence and thus the damages. While Foucault’s concepts of discipline and security guide the below analysis, we also ‘disenter’ and re-embed them in our context. We further take Karlsen and Villadsen’s suggestion that contemporary health campaigns need to arbitrate the longstanding tension between asceticism and hedonism.

Health campaigns and HIV prevention: a brief review?

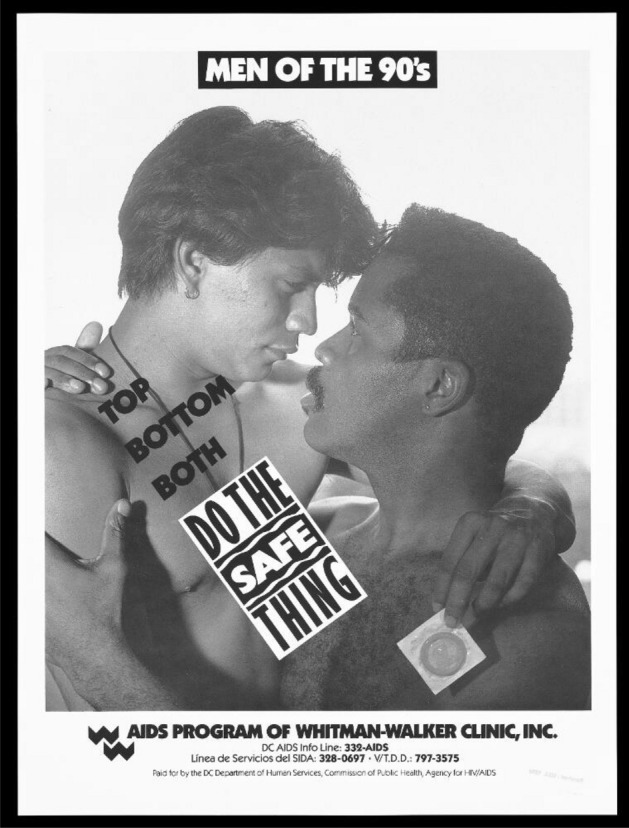

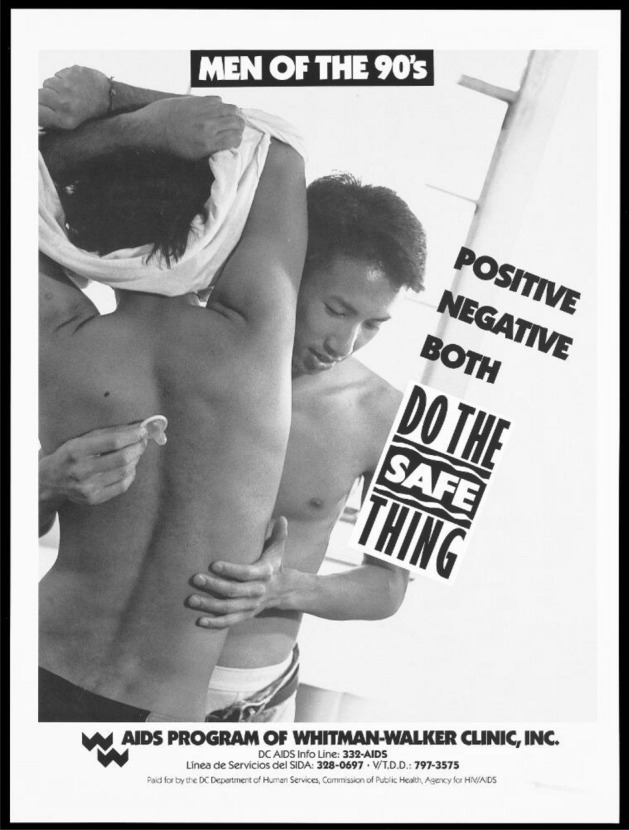

So far, governmentality-inspired health studies have tended to focus on “the direction of human conduct” in terms of responsibility and rational risk management (Rangel and Adam 2014; Joyce 2001; Petersen 1997). Because health promotion is typically identified with prohibitive morality and responsibilization, scholars tend to overlook recent health campaigns that embrace rather than suppress the drivers of pleasure and sexual identity. In the case of HIV prevention, health campaigns have been especially interesting because they can raise awareness of safe sex practices, HIV testing, and access to HIV treatment. Previous research on condom promotion is especially useful in this connection, as PrEP and condom usage, along with antiretroviral treatment, now co-exist in the HIV-prevention ecology. Research on condom promotion, particularly in visual health campaigns, has found that condom usage in an HIV context has been promoted through visual rhetoric playing on humour, fear, and, more rarely, sex (Jo-Yun and Rodriguez 2015). Studying “the condom in the age of AIDS”, Deborah Lupton mapped how Australian news media used rhetoric promoting condoms as “lifesavers”, “weapons against AIDS”, “reliable”, and “provid[ing] a responsible, and mature way to have sex” (Lupton 1994, p. 314), but also as something that “promote[s] promiscuity”, “spoils spontaneity, is a passion killer”, and “encourages homosexuality” (Lupton 1994, p. 314). Back in 1994, long before PrEP, Lupton concluded her study by saying that unless associated with pleasure and lust, condoms would never surmount the traditional negativity surrounding them and so their constant use would never be accepted (Lupton 1994, p. 317). This call from Lupton evinces the divided discourse on safe sex and HIV prevention: some discourses have been sex-negative as well as highly disciplinary and moralizing, while others have promoted sex-positive messages. Not invented to prevent HIV, the condom was, however, converted as a prevention tool once the epidemic took shape. As such, although behavioural changes and condom use for protection were in focus be PrEP, juxtaposing the condom and PrEP as preventive technologies is ill-advised. This is because condoms were converted for HIV prevention, but also because condom campaigns unfolded in a different landscape; mass publics were the audience through the mass-media channels of the 1980s and 1990s. PrEP, however, has entailed a targeted marketing campaign that also spans the internet and digital cultures like dating apps and online news forums. Still, this is not to say that pleasure, affect, and sex have been omitted from condom campaigns in the age of HIV, as the following posters from two different HIV health campaigns illustrate.

A Latino man embraces an African-American man holding a condom in an advertisement for safe sex and the AIDS Program by the Whitman-Walker Clinic, Inc. Lithograph. Wellcome Collection. Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

A Latino man holding a condom embraces another removing his T-shirt in an advertisement for safe sex and the AIDS Program by the Whitman-Walker Clinic, Inc. Lithograph. Wellcome Collection. Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

As the above images attest to, intimacy, sexuality, and pleasure were part of HIV-preventive campaigns well before PrEP. In a scoping article from 2006, Philpott et al. produced a project called “The Global Mapping of Pleasure”, mapping projects and organizations worldwide that “put pleasure first in HIV prevention and sexual health promotion, and sexually provocative media that include safer sex” (Philpott et al. 2006, p. 23).

However, early social marketing efforts often made fear-based appeals (DeJong 2001), including sex-negative and prescriptive language such as “know your status” and “get tested” (Keene et al. 2020). Health campaigns and HIV prevention also deployed such shock tactics as the threat of death, suffering, and social exclusion (Albarracín et al. 2005; Fairchild et al. 2018; Philpott et al. 2006). Notably, Keene et al. argue,

“as biomedical innovations in HIV prevention have been optimized and marketed, the nature of prevention messaging informing awareness campaigns has shifted” (2020, p. 2). Another shift in HIV prevention is that sex-negative approaches have apparently become less persuasive than sex-affirming strategies (Fairchild et al. 2015; Wansink and Pope 2015). Finally, input from affected communities and stakeholders has increasingly led to HIV prevention campaigns that acknowledge and encourage healthy aspects of sex, such as pleasure, love, and intimacy (Keene et al. 2020, p. 3).

These shifts are important, but we would further like to tease out how PrEP also inserts a new temporal dimension. As stated, our cues come from Race’s work on the “planned slipup” as well as emerging theoretical and empirical scholarship focused on these precise tensions between pleasure and pre-emption, discipline and desire, sex and calculation. Nevertheless, how these tensions are represented in visual PrEP posters promoting PrEP use has received little attention. In this context, we hope our analysis will offer a timely intervention in the governmentality studies of healthcare generally and in HIV prevention research specifically.

Materials and methods

Theoretically and methodologically, our study follows the work of Roland Barthes in his Image, Music, Text (Barthes 1977). Focusing on the rather trivial fact that these images appear to the viewer as health promotion, we followed Barthes’s first step, which was to “decode the image”, that is, to contextualize the images as belonging to a health promotion discourse. However, following Barthes, we then analysed the images according to a tri-part typology: a linguistic message and two types of iconic messages.

The linguistic message might be captions, headlines, and any other textual bits meant to guide the viewer of an image or, in this case, a poster. As Barthes states, the linguistic message is intended to guide the viewer, helping to anchor the meaning of the image insofar as it propels the viewer towards some meanings while avoiding others (Barthes 1977, p. 156). The linguistic message, as such, serves to denote, that is, to help describe, the scene being portrayed. However, the linguistic message also aids in settling the connotations of the image, which brings us to the two iconic messages that Barthes invokes as a premise for analysing images.

Images in this optic contain two iconic messages—one coded, the other non-coded (Barthes 1977, p. 154). For our purposes it suffices to highlight the following aspects of the iconic messages embedded in any visual imagery. First, no image is free of connotations and therefore cannot be purely denotative or representative. This is particularly true of advertising imagery and, in our case, health campaigns. Indeed, Barthes states that “in advertising the signification of the image is undoubtedly intentional; the signifieds of the advertising message are formed a priori by certain attributes of the product and these signifieds have to be transmitted as clearly as possible” (Barthes 1977, p. 151). This mechanism of connotation is pertinent when one analyses health campaigns such as the PrEP posters analysed here. Such posters offer a set of meanings open to interpretation, but their strong cultural coding means that the bandwidth of interpretation is highly controlled. Certain contextual structures, including metaphors, visual allegories, and metonyms, limit the set of meanings images express to their viewers. “The image, in its connotation, is thus constituted by an architecture of signs drawn from a variable depth of lexicons” (Barthes 1977, p. 160). In the following, we want to highlight how the images we have analysed incorporate symbols and imagery connoting freedom, intimacy, and spontaneity while also emphasizing control, planning, anticipation, and pre-emption.

In seeking to follow up Race’s work on the temporal dimensions of and tensions between pleasure and planning, we found ourselves particularly drawn to images that played on concepts like planning, control, play, spontaneity, and sex.

We used the Building Healthy Online Communities’ (BHOC) database to search for posters that fit our iconographic criteria. The BHOC, as its webpage states, “is a consortium of public health leaders and gay dating website and app owners who are working together to support HIV and STI prevention online”.1 In many ways, the BHOC functions as a clearinghouse for HIV and STI prevention ads, a place that online dating app companies can contact and collaborate with in addition to public health authorities. Partners on the public health side include “San Francisco AIDS Foundation, National Coalition of STD Directors, NASTAD, AIDS United, and Project Inform. They continue to take active roles in informing and implementing BHOC efforts”.2 Moreover, we found that apps and online dating sites such as Adam4Adam, BarebackRT, and SCRUFF have all collaborated with BHOC.3 The BHOC clearinghouse contains a search option for finding material in its databases. For our search, we entered the simple keyword “PrEP”. This yielded a total of 10 PrEP campaigns. Searching through these campaigns, we found two with materials matching our search for images playing on temporality, desires, pleasure, and sex. One was the Get Liberated, Getting to Zero, Silicon Valley Santa Clara County PrEP campaign, and the other was the #PrEP4Love, organized by the AIDS Foundation in Chicago. We then conducted a less systematic Google image search for PrEP posters. Using an explorative and pragmatic strategy, we searched for specific terms to select posters matching our search criteria.

We used the following key terms “HIV PrEP + control”, “HIV PrEP + play”, “HIV PrEP + pleasure” and “HIV PrEP + desire”. Although not systematic, the search yielded material that matched our criteria. Two health campaigns in particular stood out: the New York City-based Play Sure campaign and the Australian ACON Ending AIDS campaign, in particular its PrEP promotion. An initial analysis of each campaign left us with the ACON campaign, which contained images that directly used imagery playing on nakedness, sexuality, and temporality. The Play Sure campaign utilized humour and intimacy, albeit with people dressed, and, as the name indicates, highlighted “playing” as a form of framing HIV PrEP use. As such, this search strategy narrowed our selection to three campaigns: the Get Liberated, #PrEP4Love and ACON’s Ending AIDS PrEP campaign.

We should note that of the 10 campaigns identified, only three fit our criteria. Although unproblematic in itself, this outcome may say something about our arguments in this article. Our findings suggest that while PrEP campaigning recognizes pleasure in certain instances, the question remains as to under what conditions this pleasure can and may occur and to what effects. What does the fact that only about a third of the campaigns were promoted and supported by platforms that circulate and support sexually explicit content say about health promotion and pleasure? While these questions are beyond the scope of this article, future research could benefit from including a focus on what drives the inclusion of pleasure in health campaigns.

We would like to note that such a search has several analytical limitations. First, we recognize that a strong bias towards the USA exists, as the BHOC is based there and its clearinghouse content consists of American campaigns. Second, the study relies heavily on health campaigns in English. Data from PrEP Watch shows that in Q2 of 2020, there were 203,837 PrEP initiations in the USA and 26,520 in Australia, numbers that can justify an emphasis on English. However, such an emphasis not only leads to an analysis concentrated on PrEP campaigns in English but also forecloses an analysis of PrEP in countries such as South Africa, Kenya, France, and Brazil, all countries that, according to data from PrEP Watch, have relatively large numbers of PrEP initiations when compared to the total number of PrEP initiations globally.

Being in the moment and getting liberated: PrEP, pleasure, and iconology

The subjects in these campaigns have the salient feature of being targets of what Karlsen and Villadsen (2016) call “non-authoritarian health promotion”, which incorporates the irrational and the pleasurable in health campaigns. Instead of repressing subjects’ unhealthy desires and pleasure-seeking habits, this form of promotion communicates by playing on pleasure and desire, a strategy we analyse below.

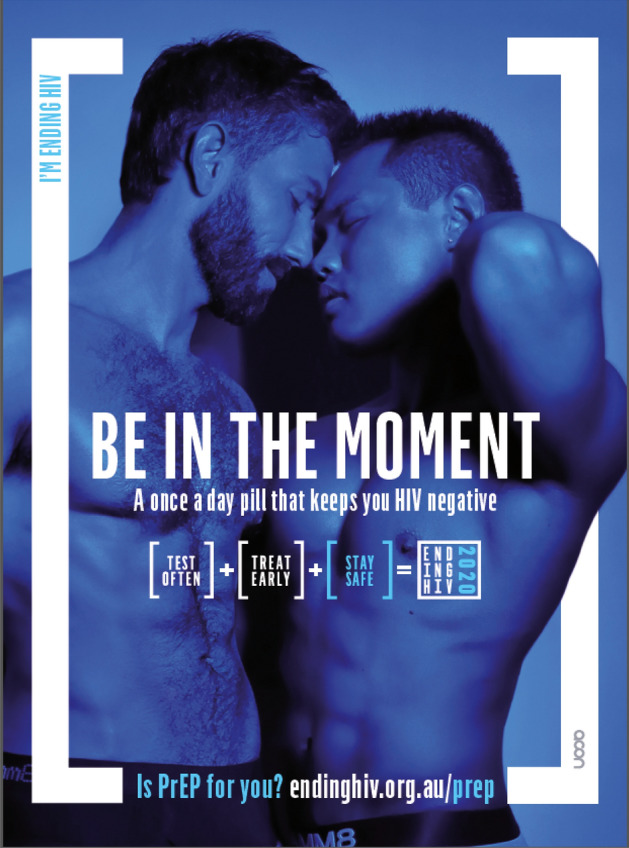

Used with permission of ACON, copyright holder

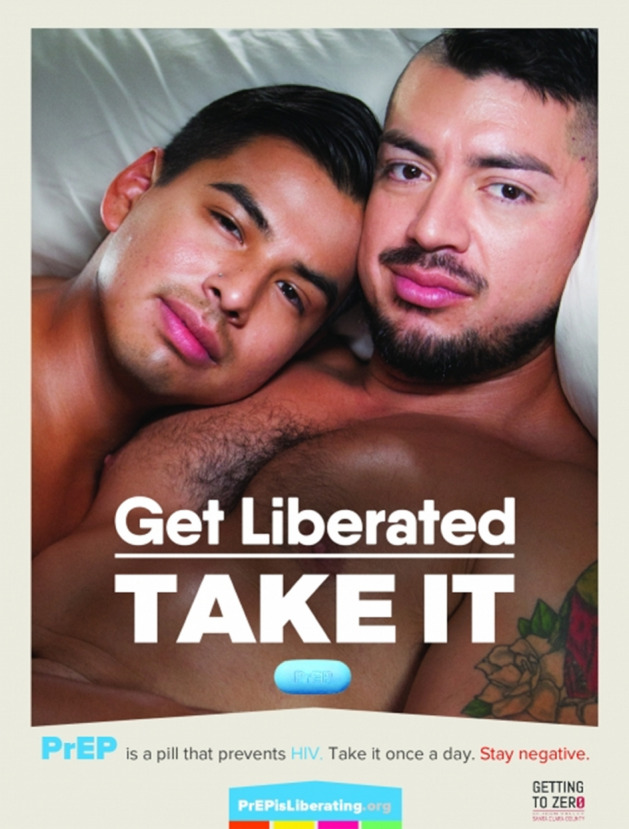

Used with permission of County of Santa Clara Public Health Department, Getting to Zero campaign.

Used with permission of ACON, copyright holder

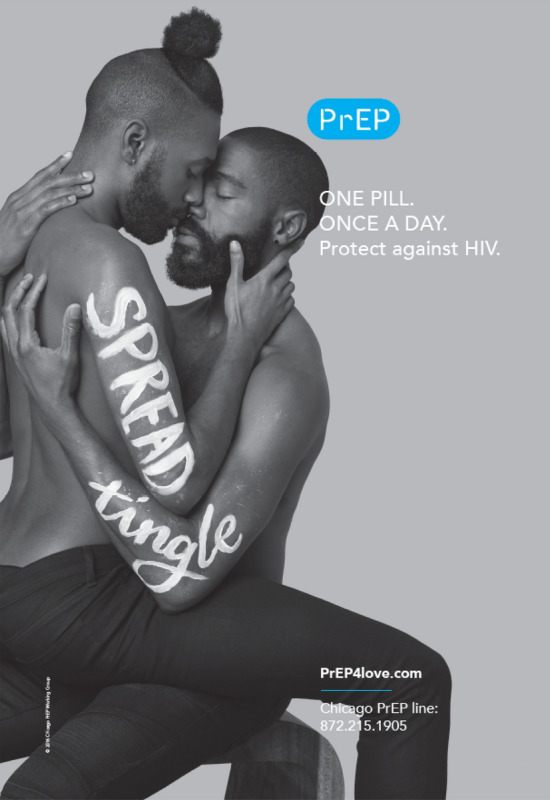

Used with permission of the AIDS Foundation Chicago, copyright Chicago PrEP Working Group

The above images contain a mix of medical ‘take-home messages’ meant to ensure that people stay HIV negative. While playing on pleasure and the freedom to enjoy sex essentially whenever the moment arises, the ads remain within the test and treatment paradigms, as evidenced in the ads’ linguistic equation of “test often”, “treat early”, and “stay safe” that will “end HIV in 2020”. As such, by emphasizing contagion, testing, and treatment, the imagery and written messages in these ads still display the disciplinary logic of risk minimization. However, contrary to campaigns highlighting only risk and contagion, these campaigns also speak to such tropes as pleasure and sex. The slogan “be in the moment” signals an almost unlimited access to pleasure and sex if only one commits to PrEP. On the other hand, the recourse to “be in control” not only alludes to sexual autonomy but also to the disciplinary aspects of having to adhere to a daily PrEP regime.

Conversely, the implicit corollary can be that HIV risk is everywhere. If PrEP offers constant protection as long as one adheres to the pill regime, then—tacitly at least—HIV risk looms ever large. Barry Adam points out that “one of the basic tenets of HIV prevention has been to warn everyone to act as if everyone else is HIV positive. It is a message that implicitly hails an HIV negative audience to practise self-protection” (Adam et al. 2005, p. 341). In the above ads, pleasure is spotlighted, yet the call to get PrEP and unfailingly take it implicitly keeps risk forever near the surface.

Inspired by Barthes, we cannot fail to note that all the above images display men in postures of intimacy. However, the connotations formed through the mixture of linguistic messages and cultural codes embedded in the images themselves present the viewer with images that connote pleasure, control, freedom, and continued health. The juxtaposition of bare-chested men in highly intimate positions with the linguistic messages creates a set of visual connotations that couples pleasure and planning, intimacy and biomedical prophylaxis. In this connection, perhaps we can wager a more daring reading of Barthes, one that draws on his distinction between the studium and the punctum (Barthes 1981). The studium characterizes how the viewer engages in the “figures, the faces, the gestures, the settings, the actions” of the photograph by way of a “classical body of information” that sets familiar cultural codes in motion (Barthes 1981, p. 26). The punctum, on the other hand, can be read as that which interrupts and opens up dominant cultural readings of a photograph to various interpretations and affects (Karlsen et al. 2018). In the above, the studium of the posters could be those well-known cultural codes for intimacy and sexuality embodied in the close proximity of naked male bodies. These in turn connote gay male sexuality, desire, and pleasure. The punctum constitutes, we suggest, the mixture between pleasure and planning, and between intimacy and biomedicine. No longer connoting risk and pleasure, the above posters open up for a coupling between pleasure and safe sex, and between being in the moment and in control.

Robert Grant and Kimberley Koester make a relevant observation regarding how the implementation of PrEP needs to transcend a purely biomedical approach to HIV prevention focused solely on risks:

PrEP programmes that focus on the strictly biological aspects, for example, medical appointments and adherence, rather than on how PrEP may align with people’s sexual and social goals could become tacitly or overtly coercive. (Grant and Koester 2016, p. 7).

This quote points to the importance of bridging the biomedical and the social in HIV preventive research and discourse. It supports what Susan Kippax has called “going beyond the distinction” between social and biomedical research in HIV (Kippax 2012; Kippax and Stephenson 2012, 2016). Rather than being framed only through the biomedical concepts of risk, adherence, and continual engagement with doctors, in the above imagery PrEP transcends an orthodox understanding of what biomedical HIV prevention can be.

As Kippax notes, almost every mode of HIV transmission is inherently social (Kippax 2011, 2012), and to a certain degree all modes of prevention are both social in nature and reliant on human behaviour (2012). As cases in point, HIV transmission depends on human interaction and intimacy, which in turn are mediated by socio-cultural scripts and, increasingly, techno-cultural networks, as several authors have highlighted. In contrast, HIV prevention is also mediated by social interactions such as peer-based interventions and health care systems; condom negotiations and safe-sex practices are often hashed out in intimate and social settings; and, finally, adherence to ARVs or PrEP might require social support and human interaction, just as adherence to pharmaceutical regimens/treatments are also mediated through human networks of support.

In Kippax’s view, however, this leads to a paradox in HIV knowledge production: the HIV field, she argues, is primarily dominated by biomedical frames of understanding and ‘knowing’ HIV, which in turn often dictates the direction of HIV research. Yet, as Kippax notes, this is clearly at odds with the inherently social nature of HIV transmission and prevention. PrEP stands at the intersection between the biomedical and the social, thus hinting at the notion of going beyond the choice of pleasure or prevention and instead integrating the two.

Anticipation, pre-emption, planning, and pleasure

Grant and Koester note that a key reason why some behavioural interventions have failed to check the HIV epidemic is that in so-called hot moments of decisions making, some ignore their knowledge regarding preventive measures (2016, p. 4). For example, a person may assess risk differently if personal preferences make condom usage impossible, if a needed condom is unavailable, or if a sense of safety or the influence of drugs is a factor (Grant and Koester 2016, p. 4). Barry Adam has noted how in the context of condomless sex between MSM, diverse rationalities come into play, including individualism, personal responsibility, consent, and contractual interactions (2005, p. 339). On this account, rationalities underpinned by neoliberal doctrines of rational choice, personal responsibility, and individualism co-exist with other orientations such as trust, romance, and proximity. PrEP campaigns have accommodated these ‘irrational’ orientations by emphasizing pleasure through responsibility.

PrEP taken in so-called cold moments of risk evaluation (Grant and Koester 2016, p. 5) allows one to experience unmitigated pleasure and have safe sex without forethought. The above poster’s reference to “being in the moment” could translate as the freedom from having to calculate risks in the heat of such a moment, as Grant and Koester note. Indeed, PrEP allows one to anticipate the risk of potential ‘hot moments’, whereas condom usage must be negotiated on the spot. As Race states, “PrEP asks HIV-negative men not only to acknowledge but also take systematic, prescribed, coordinated and involved action against a risk that one may not be inclined to acknowledge so readily” (2018, p. 106). The entanglement between the calculative and pre-emptive ‘cold moments’ of PrEP and the ‘hot moments’ of sexual pleasure might not only open up for a new temporality of pleasure/prevention, but also inform a reading of pleasure as an aspect of harm reduction, as Race has argued (Race 2008). Drawing on Foucault’s work concerning the distinction between ars erotica and scientia sexualis (Foucault 1990, 2012), Race notes that “pleasure is an event that draws on certain pedagogical practices and technical arrangements, in which what is learnt is not only how to identify and experience certain effects, but also frames for appreciating and moderating these effects: how to conduct the practice to achieve certain desirable states” (Race 2008, p. 420). Race is important here because he also points to the broader issue of harm reduction strategies and their use as public health interventions. His work on pleasure as harm reduction, particularly as it relates to illicit drug use but also to PrEP, ostensibly result from an engagement with the struggle to include such harm reduction approaches in public health and in health campaigns. Although not the specific subject of this analysis, such a perspective resonates with our own take on the role of pleasure in PrEP campaigns.

Earlier HIV promotions that utilized prescriptive language such as “Know your status!” or “Get tested!” stand in contrast to the imagery of the above posters, which might be read as producing a pedagogy of learning to PrEP for pleasure. In such a reading, pleasure and planning become part of the event of pleasurable sex rather than a tool of biopolitics. Through these images, the viewer “learn[s] to identify certain effects as enjoyable, but also to interpret and prevent other effects” (Race 2008, p. 421). In the above images, these effects might be intimacy, sex without a condom, sexual pleasure, or love. Conversely, other prevented effects include the risk of HIV infection and the mental anguish of fearing one. As such—and this is a key point in our article, its being tied to our focus on temporality— “pleasure is not the antithesis of self-regulation and safety, but the medium through which certain shared protocols of safety take shape” (Race 2008, p. 421). PrEP campaigns can be said to be part of such protocols; that is, they are included in a discourse of consumer-directed commercials as well as entangled with what Tankut Atuk has called “pathopolitics” (Atuk 2020). However, the above PrEP imagery does not project pleasure as an obstacle to self-regulation and safety, but rather sets up PrEP as a protocol, so to speak, which defers self-regulation to the previously addressed ‘cold moments’ of calculation. However, rather than claiming that pleasure itself (as an affective state or an event) is the medium, we postulate that PrEP is the medium that mediates, that is, lies between, planning and pleasure, between the coordinated moment of consuming PrEP and the moment of pleasurable sex, thus calling forth a shared protocol for safe sex and thus also pleasure.

The above imagery “contests moralizing strategies of control by devising measures for safety grounded in existing embodied practices … Today, many of the best educational strategies work by contextualizing prevention techniques in terms of the situations within which people elaborate techniques of pleasure” (Race 2008, p. 421). While these posters clearly belong to a visual culture highly influenced by market capitalism and ‘direct-to-consumer’ commercials, the BHOC has involved various stakeholders, ranging from app owners and public health officials to representatives from NGOs and queer communities, as a way of including perspectives on sex and pleasure for use in different PrEP campaigns. This inclusion ensures at least some measure of grounding in gay men’s everyday sexual practices and those practices’ entanglement with PrEP.

We would now like to return to our focus on the temporal dimension of the notions Race has also alluded to: anticipation, calculation, and pre-emption, which in the above-mentioned campaigns closely interconnect with the spontaneous, the pleasurable, and the playful. Adam has noted that “HIV prevention messages implicitly exhort people to act safely now in order to preserve themselves for the future. To be effective, then, the prevention message calls on an autobiographical narrative that life is worth living, and that something done now makes sense because the future will be a desirable place in which to arrive” (Adam 2006, p. 172, our italics). Adam spotlights how gay men’s experience of trauma spurs a caring attitude towards their health, but insofar as they need to feel that life is worth living to take up condom usage, his study reflects the temporal logic in HIV-prevention practices.

Taking PrEP induces the individual to pre-emptively anticipate pleasure in the future and thus adopt the premise that efforts to prevent HIV risk now will engender a future that is literally a ‘desirable place’. These observations on PrEP practices challenge more explicit, critical views that gay men’s engagement with biomedical treatment and prevention technologies advances the culture of neoliberal consumerism. Indeed, as Kane Race and Martin Holt emphasize, the often-creative co-production of biomedical technologies and GBM communities is also entangled with drugs, HIV preventive technologies, and pleasure (Holt 2014, 2015; Race 2015a, 2017). Similarly, da Silva-Brandao and Ianni note that “while on PrEP, individuals find new possibilities of managing their sexual practices and ways to transform their experience of pleasure and desire during sexual practices … PrEP can facilitate the fulfilment of sexual fantasies such as condomless sex, relieving fears of its users” (da Silva-Brandao and Ianni 2020, p. 1401). In this regard biomedical technologies such as PrEP play an important role in an assemblage of technologies that enable (and foreclose) new ways of experiencing and engaging with sexual practices (Preciado 2013; Race 2009, 2015a, b, 2016).

Using the notion of the well-balanced subject, we direct attention to how PrEP allows the subject to defer any risk calculations until the moments before, or outside of, the sexual encounter itself. This deferral does not relieve the subject of having to calculate risk or meet disciplinary demands; after all, adhering to PrEP is disciplinary in an almost literal sense, as the individual must stick to a regime of taking a measured daily dose of PrEP. However, the well-balanced subject in our analysis relegates their risk calculations to times and places other than those dictated by, say, condom usage. Risk calculation becomes a pre-emptive strategy that allows the PrEP user to be not only in the moment but also in control, as the posters so vividly proclaim.

These observations resonate with users’ declared motivations for taking PrEP. Grant and Koester note that PrEP users report that their decision to submit to medication is based not only on safety concerns but also on the heightened pleasure they could experience (Grant and Koester 2016, pp. 5–7). Other factors include adaptability, a sense of empowerment, reduced psychological stress and anxiety, and the bonds fostered through love and care (Grant and Koester 2016, pp. 5–7). However, this optimistic framing of PrEP becomes complicated in view of its also having been linked to ‘promiscuity’ and regarded as a ‘fun’ pill for reckless people. Notably, Pawson and Grov’s study on attitudes to PrEP amongst MSM in New York shows how PrEP becomes both a contentious issue and a basis for distinguishing the ‘deserving’ PrEP users from the ‘undeserving’ (Pawson and Grov 2018, p. 1396).

From a security rationality perspective, which regards diseases and epidemics as ever-present, PrEP manifests a preventive strategy that seeks to minimize the impact of HIV while recognizing that, because pleasure is a fundamental behavioural driver, some risk of infection will always exist. Furthermore, PrEP does not constitute a conventional treatment regimen involving disciplinary controls like monogamy or abstinence, as such a regimen demands a—metaphorical—sexual quarantine that hinders pleasure and viremia from circulating. On the contrary, PrEP accepts desire and intimacies, while also enabling a person to minimize their risk of infection by consuming biopharma. In this context, discipline and security are not fundamentally at odds, but rather reinforce each other. Accordingly, the ‘well-balanced subject’ can be understood as the synthesis that occurs when a disciplinary logic becomes intertwined with securitization. The imagery of the campaign ads plays on intimacy, the biomedical use of pharmaceuticals, and the idea of liberation, which seems to take three forms: a temporal liberation from the endless imperative to evaluate risk in every sexual encounter, a liberation from the fear of HIV infection, and, finally, the liberty to be intimate without anxiety. Once again, Grant and Koester highlight how emerging ethnographic research and surveys show that people choose PrEP for reasons other than simply ensuring they can practise riskier sex with more partners (2016, p. 6). Even people with a limited number of partners report that they principally take PrEP for the comfort of knowing they are ‘safe’ and protected, a factor that points to psychological aspects of PrEP extending beyond unmediated pleasure and sex (Grant and Koester 2016, p. 6). Although not conveying that anything goes, the message in these PrEP ads reconstitutes discipline in a new temporal logic of pre-emption, planning, and subsequent pleasure. PrEP introduces a new temporal axis within HIV prevention, an axis that we analysed through the lenses of discipline and security. The disciplinary axis resides in each individual’s obligation to take PrEP before and after sexual encounters. In turn, the security axis constitutes the temporality that individuals open up by adhering to PrEP and that thus enables them to put desire and pleasure first, while risks temporarily recede.

Risk and responsibility

While the above campaigns do not explicitly articulate the conventional theme of responsibility, we will briefly link our analysis of temporality, pleasure, discipline, and risk to this theme. Risk and responsibility have been conceived as interrelated concepts that support each other, in particular within HIV prevention. The “calculating, rational, and self-interested subject”, writes Adam (2003), has often been linked to the paradigmatic subject of contemporary neoliberalism (Adam 2006, p. 169). This subject takes responsibility for their health and mitigates risk through “rational actor theory” and prudent calculation in “the marketplace of life”. Adam notes that notions of responsibility for HIV prevention have historically tended to fall more heavily on the shoulders of people living with HIV than on those who are HIV negative (Adam et al. 2005, p. 337). In addition, notes Adam, the responsibilization of safe sex practices has increasingly been rearticulated as individuals’ fundamental obligation to maintain their own health and protect themselves from external perils (Adam et al. 2005, p. 337). In the above images, responsibility lies in the subject’s taking PrEP in cold moments in order to “be in the moment” in a future where sex is projected to occur. This new constellation of anticipation, risk, and pleasure serves to relocate responsibility temporally in regard to condom usage or other safer sex practices.

While condom usage and other safer sex practices always occur within the temporal moment of pleasure and sex, PrEP routines take place outside of these moments.. Responsibility for safer sex practices is thus exercised in the same temporal frame as the sex itself. Conversely, the responsibility for safe sex, as mediated through PrEP, is settled outside of these temporal frames, thus linking anticipation to responsibility and trust. The present discourse “no longer revolves around irresponsible outlaws that must be disciplined by medical knowledge, but disciplined patients who request for themselves a disciplined status on behalf of freedom. The individual disintegrates perceived biopower framings into liberating forms of sexualities despite being highly disciplined” (da Silva-Brandao and Ianni 2020, p. 1409). We agree with da Silva-Brandao and Ianni here, but also point out that any notion of a linear historical transition from discipline to pleasure in public health campaigns during the HIV era is misleading. Indeed, such campaigns have existed and vied for attention since the HIV epidemic began. For example, in 1983 the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York pioneered a pamphlet called “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic” (Berkowitz et al. 1983), which in many ways promoted liberating forms of sexualities based on clearly disciplinary harm reduction strategies that allowed one to not only avoid HIV infection but also have sex during an epidemic.

Returning to the issue of PrEP, we note that this touches on a question beyond the tension between pleasure and pre-emption: if PrEP offers new ways of experiencing pleasure while still being highly contingent on discipline, can pleasure stand fully outside the domain of biopower? Although Foucault stated that bodies and pleasure are the only sites wherein resistance to biopower is possible (Foucault et al. 2003), we might highlight a point raised by Tankut Atuk. Atuk states that if biopower appears to overdetermine pleasure, it is because “I do not believe that pleasure stands outside the realm of biopower: that is, pleasure can resist biopower precisely because it operates within not outside” (Atuk 2020, p. 8). However, Atuk also raises the important potential of PrEP to provide radical queer alternatives to normative sexual practices when it is not purely framed as a biomedical HIV-preventive tool to be consumed in the name of public and individual health (Atuk 2020, p. 8). The transgressive potential of PrEP to reconfigure sexual practices, Atuk suggests, lies in its usage outside the domain of health rather than within the domain of pleasure. PrEP differs from a conventional disciplinary regime precisely because one takes PrEP in cold moments of introspection (Grant and Koester 2016) and thus pre-emptively anticipates risky sex. Accordingly, the campaign’s premise could be condensed into this dual doctrine: without risk management, no pleasure—and without pleasure, no effective risk management.

This tolerant and inclusive approach to norms can be related to Foucault’s notion of biopower, as rendered by Jeffrey Nealon:

Although such highly politicized disciplinary identities are of course consistently defined by their distance from the ‘norm’, such normative discourse doesn’t function to exclude persons, topics or acts; rather norms do their work precisely by trying to include – which is to say, examine, test, and classify – as much data as possible. (2009: 50)

In this reading, HIV prevention is not ultimately about harnessing individuals and correcting them to match norms predefined by expertise, but rather about accommodating the dynamics and (perhaps unexpected) potentials inherent in their lives and lifestyles. Nealon writes: “At the end of the Foucauldian day, the danger and productivity of norms lies not in their proclivity to exclude people or practices, but rather in their intense and insatiable desire to include, to account for, virtually everything” (2009, p. 50). Inspired by Foucault’s play on the French words gouverner and conduire in The Subject and Power (Foucault 1982), we situate the PrEP campaigns within the broader problematic of “the conduct of conduct”. Fundamentally, these campaigns strive to direct the subject towards a specific self-conduct.

In this light, one could argue that PrEP campaigns with sexually explicit images or language would not surprise Foucault.

Conclusion: no discipline without pleasure

This article has explored the ongoing transformation in the governmentality of health promotion that seeks to integrate pleasure with rational appeals to minimize risk. Promoting pleasure in HIV prevention is not entirely novel (Mabire et al. 2019, p. 11), but, as this article has demonstrated, and as Mabire et al. (2019, p. 11) observe, studies on PrEP promotion must take into account new modalities of health campaigning focused on balancing pleasure and discipline. Inspired by Foucault, we suggest that the contemporary preventive regime should be viewed as a transformation at the intersection of discipline and security. Consequently, the subject begins to appear in a dual fashion: on the one hand, as an element in an exposed population whose risks and infection patterns are registered and sought minimized, and, on the other, as a specific individual whose habits, values, and pleasure must be recognized. A dual subjectivation can hence be identified within PrEP, one that plays on ‘irrational’ pleasure and another that stresses ‘rational’ risk management.

While our main argument pivots on issues other than access to PrEP, we acknowledge that our ‘well-balanced subject’ is envisaged as someone that can access PrEP. Since PrEP access varies both globally and regionally, our analytical points should be further developed from this perspective. To be sure, one’s ability to be in the moment and to balance pre-emption and pleasure inevitably hinges on socio-economic factors as well as on structural issues, such as how healthcare systems in different national and regional contexts fund and promote PrEP. Health ads like those examined here are therefore in danger of targeting only subjects with the means to access PrEP, thus perpetuating existing inequalities within HIV prevention. Thus, the well-balanced subject that emerges from our material should not be understood as a generalizable or hegemonic figure, but more as an emerging theme in contemporary health prevention.

In our case, security depended on discipline—a condition that PrEP satisfied by encouraging pleasure and desire if, and only if, people at risk discipline themselves by taking PrEP. When transferred onto large population groups, security requires individuals to discipline themselves, but since scale is important here, securitization strategies can tolerate some slip-ups at the individual level as long as enough people undertake self-disciplining normalization. The securitization of HIV prevention through PrEP covered here hinges on disciplinary pre-emption and planning, but also allows for pleasure and desire. However, this integration only works as long as a sufficiently high segment of the exposed population adheres to PrEP regimes.

Our Foucauldian approach distinguishes itself from the health prevention literature and from critical sociology of health more broadly, as it emphasizes historical continuities as well as discontinuities with, for instance, condom campaigns. Moreover, we have tried to show that pleasure is not the antithesis of self-control and safety, as it is not portrayed as such in our material. Gagnon, Jacob, and Holmes have argued that public health campaigns often deploy fear-based rhetoric: “as a bio-political technology, fear is productive if each individual consumes fear and is consumed by it; thus, the overall population must be possessed by the impending disaster and its potential consequence on the self. Fear is, therefore, a bio-political technology that creates a state of permanent (in)security and manipulates individuals who buy into this mode of control” (Gagnon et al. 2010, p. 252).

While we agree that risk and fear still constitute significant preventive strategies, we suggest that the emergence of pleasure in HIV prevention calls for a more nuanced view of fear and risk as the only predominant rationalities. We wish to ask whether profit has co-opted pleasure through PrEP, and whether such pleasure targets the body not in the name of health but in the name of ‘the patient-as-consumer’. In other words, has PrEP through pleasure ‘reterritorialized’ the body as a site of consumption and thus surplus profit? Preciado advances this conclusion: “it is not power infiltrating [the body] from the outside, it is the body desiring power, seeking to swallow it, eat it, administer it, wolf it down, more, always more, through every hole, by every possible route of application” (Preciado 2013, p. 208).

Like critical sociology of health scholars, we operated on the general premise that risk must be studied as socially constructed, but we narrowed our analytical framework by applying specific Foucauldian concepts. Hence, our study showed that PrEP reconstructed risk when it was articulated there where the rationality of discipline and of security intersected. Our analysis was less about confirming that these rationalities can be identified in the campaigns and more about using them as guiding lenses while also emphasizing the interplay and tensions between disciplinary and permissive messages in their own right. Eschewing the assumption that discipline and security designate two distinct objects of analysis, we have sought to provide a conceptual vocabulary suited for studying novel, more permissive forms of health campaigning emerging in the HIV domain and beyond.

Recent PrEP campaigns exhibit both continuity and discontinuity with conventional strategies for creating a healthy body through discipline. The formation of a well-balanced subject in relation to PrEP usage requires subjects that discipline themselves differently, that is, use other means at other times in other spaces than the subject targeted in conventional campaigns for condom usage. PrEP subjects do not ultimately escape disciplinary health regimes, as they are impelled to strictly adhere to daily pill regimes. However, they are also encouraged to be in the moment and enjoy the related pleasures of intimacy and gratification. In this novel take on health promotion, discipline is not only imposed externally but rather fully embodied and taken up in sexual subjectivity.

Throughout our analysis, we have dialogued with recent HIV scholarship within the broader sociology of HIV/AIDS. Much of this literature resonates with our observations insofar as our campaigns for a well-balanced subject hinge on a similar integration of the apparently distinct domains of the biomedical and the social. However, our contribution identifies a new temporality that has emerged in recent PrEP campaigns, one where the disciplining of subjectivities integrates the target groups’ desire for pleasure and the thrills of sexual spontaneity. As regards previous subjectivation strategies in health prevention, the key difference this well-balance subject manifests is the constant adjustment that PrEP demands: pre-emption and planning at cold moments in anticipation of future moments where the subject can act freely and spontaneously enjoy the experience.

Biographies

Tony Sandset

is Research Fellow at Center for Sustainable Healthcare Education at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo. His current research focuses on knowledge translation within the field of HIV care and prevention. Specifically, his focus is on how medical knowledge from randomized controlled trials is mediated, how evidence is generated in HIV prevention and how new medical technologies informs subjectivities, desire, and sexuality. Another of his research areas pertains to the intersection between race, gender, class and HIV care and prevention. He is the author of the book Color that Matter: A Comparative Approach to Mixed Race Identity and Nordic Exceptionalism, 1st Edition (Routledge) and the book, Ending AIDS in the Age of Biopharmaceuticals (Routledge).

Kaspar Villadsen

is Professor at the Department of Management, Politics and Philosophy, Copenhagen Business School. He is the author of the books Power and Welfare: Citizens’ Encounters with State Welfare (coauthored with Nanna Mik-Meyer, Routledge, 2013) and Statephobia and Civil Society: The Political Legacy of Michel Foucault (co-authored with Mitchell Dean, Stanford University Press, forthcoming). He has published on Foucault, organizations, biopolitics and welfare policy in Economy and Society, Theory, Culture & Society, Organization, Constellations, Social Theory and Health and more. His current research is on governmental technologies, health promotion, and the problem of state and civil society.

Kristin Heggen

is the Dean of Education at the Faculty of Medicine, at the University of Oslo and Professor of Health Sciences. She also heads the Faculty’s Health Sciences Education Center (HUS) where research, education and dissemination of sustainability goals is one of the focus areas. In her extensive academic career, she has had a special interest in knowledge, knowledge policy and power related to welfare professions and policies. She is currently in the University of Oslo’s Rector’s Group for a planned commitment to sustainability goals. The following two publications are of significant relevance for the book project:

Eivind Engebretsen

is a professor of medical science theory, the Research Director at the Faculty of Medicine and head of the research group for knowledge transfer and knowledge translation in the health service (KNOWIT). He has marked himself internationally through research on issues in implementation processes and knowledge-based practice. He has contributed to the renewal of medical humanities (in collaboration with philosopher Julia Kristeva) and has focused on dilemmas in the implementation of sustainability goals in the health field (e.g. through 3 Lancet publications). He has also written and edited several books.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

See the BHOC webpage for more: https://www.bhocpartners.org/about-bhoc/#toggle-id-1.

See the BHOC webpage for more: https://www.bhocpartners.org/about-bhoc/#toggle-id-1.

See the BHOC webpage for more: https://www.bhocpartners.org/about-bhoc/#toggle-id-1.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adam BD. Infectious behaviour: Imputing subjectivity to HIV transmission. Social Theory & Health. 2006;4(2):168–179. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adam BD, Husbands W, Murray J, Maxwell J. AIDS optimism, condom fatigue, or self-esteem? Explaining unsafe sex among gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(3):238–248. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albarracín D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho M-H. A test of major assumptions about behavior change: A comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(6):856. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atuk T. Pathopolitics: Pathologies and biopolitics of PrEP. Frontiers in Sociology. 2020;5:53. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthes R. Image-music-text. London: Macmillan; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes R. Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. London: Macmillan; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Crimp D. How to have promiscuity in an epidemic. AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism. 1987;43:237–271. [Google Scholar]

- Crimp, D. 1988. AIDS: Cultural analysis, cultural activism. Cambridge: MIT.

- Crimp D. Melancholia and moralism: Essays on AIDS and queer politics. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva-Brandao RR, Ianni AMZ. Sexual desire and pleasure in the context of the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) Sexualities. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1363460720939047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Wolf RC, Austin SB. US federally funded television public service announcements (PSAs) to prevent HIV/AIDS: A content analysis. Journal of Health Communication. 2001;6(3):249–263. doi: 10.1080/108107301752384433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: Critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):13–18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AL, Bayer R, Colgrove J. Risky business: New York City’s experience with fear-based public health campaigns. Health Affairs. 2015;34(5):844–851. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AL, Bayer R, Green SH, Colgrove J, Kilgore E, Sweeney M, Varma JK. The two faces of fear: A history of hard-hitting public health campaigns against tobacco and AIDS. American Journal of Public Health. 2018;108(9):1180–1186. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. The subject and power. Critical Inquiry. 1982;8(4):777–795. doi: 10.1086/448181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. 1990. The history of sexuality: An introduction, vol. I. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage.

- Foucault, M. 2000. Ethics: Subjectivity and truth: The essential works of Michael Foucault, 1954–1984, vol. 1. London: Penguin.

- Foucault M. Security, territory, population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–78. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. What is critique? In: Foucault Michel., editor. The politics of truth. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e); 2007. pp. 23–83. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. 2012. The history of sexuality, vol. 2: The use of pleasure. New York: Vintage.

- Foucault M. The Punitive Society. Lectures at the Collège de France 1972–1973. Houndmills: Palgrave; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M., M. Bertani, A. Fontana, F. Ewald, and D. Macey. 2003. “Society Must be defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976, vol. 1. London: Macmillan.

- Gagnon M, Jacob JD, Holmes D. Governing through (in) security: A critical analysis of a fear-based public health campaign. Critical Public Health. 2010;20(2):245–256. doi: 10.1080/09581590903314092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Koester KA. What people want from sex and preexposure prophylaxis. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2016;11(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/coh.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EC, Witte K. Can fear arousal in public health campaigns contribute to the decline of HIV prevalence? Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(3):245–259. doi: 10.1080/10810730600613807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt M. Gay men's HIV risk reduction practices: The influence of epistemic communities in HIV social and behavioral research. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2014;26(3):214–223. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt M. Configuring the users of new HIV-prevention technologies: The case of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(4):428–439. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.960003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce P. Governmentality and risk: Setting priorities in the new NHS. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2001;23(5):594–614. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.00267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jo-Yun L, Rodriguez L. Appeals, sexual images, visual metaphors and themes: Differences in condom print ads across four continents. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies. 2015;5(3):37. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen, M.P., B.M. Sørensen, and K. Villadsen. 2018. The boy on the beach: The photographic event that contested the violence of European governmentality. In Borderland religion: Ambiguous practices of difference, hope, and beyond, 136–159. London: Routledge.

- Karlsen MP, Villadsen K. Health promotion, governmentality and the challenges of theorizing pleasure and desire. Body & Society. 2016;22(3):3–30. doi: 10.1177/1357034X15616465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keene LC, Dehlin JM, Pickett J, Berringer KR, Little I, Tsang A, et al. # PrEP4Love: success and stigma following release of the first sex-positive PrEP public health campaign. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2020;23(3):397–413. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1715482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S. Effective HIV prevention: The indispensable role of social science. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2012;15(2):17357. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S, Stephenson N. Beyond the distinction between biomedical and social dimensions of HIV prevention through the lens of a social public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(5):789–799. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax, S., and N. Stephenson. 2016. Socialising the biomedical turn in HIV prevention. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1351650.

- Koopman C, Matza T. Putting Foucault to work: Analytic and concept in Foucaultian inquiry. Critical Inquiry. 2013;39(4):817–840. doi: 10.1086/671357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff A. Real-time biopolitics: The actuary and the sentinel in global public health. Economy and Society. 2015;44(1):40–59. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2014.983833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton D. The condom in the age of AIDS: Newly respectable or still a dirty word? A discourse analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 1994;4(3):304–320. doi: 10.1177/104973239400400304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mabire X, Puppo C, Morel S, Mora M, Rojas Castro D, Chas J, et al. Pleasure and PrEP: Pleasure-seeking plays a role in prevention choices and could lead to PrEP initiation. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2019;13(1):1557988319827396. doi: 10.1177/1557988319827396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell WT. Iconology: Image, text, ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Palmgreen P, Chabot M, Dobransky N, Zimmerman RS. A 10-year systematic review of HIV/AIDS mass communication campaigns: Have we made progress? Journal of Health Communication. 2009;14(1):15–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730802592239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson M, Grov C. ‘It's just an excuse to slut around’: Gay and bisexual mens’ constructions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (Pr EP) as a social problem. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2018;40(8):1391–1403. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A. Risk, governance and the new public health. In: Petersen A, Bunton R, editors. Foucault: Health and medicine. London: Routledge; 1997. pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott A, Knerr W, Boydell V. Pleasure and prevention: When good sex is safer sex. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14(28):23–31. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preciado PB. Testo junkie: Sex, drugs, and biopolitics in the pharmacopornographic era. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Race K. The use of pleasure in harm reduction: Perspectives from the history of sexuality. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008;19(5):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race K. Pleasure consuming medicine: The queer politics of drugs. Durham: Duke University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Race K. Reluctant objects: sexual pleasure as a problem for HIV biomedical prevention. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 2016;22(1):1–31. doi: 10.1215/10642684-3315217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Race K. The gay science: Intimate experiments with the problem of HIV. London: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Race K. ‘Party and play’: Online hook-up devices and the emergence of PNP practices among gay men. Sexualities. 2015;18(3):253–275. doi: 10.1177/1363460714550913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Race K. Speculative pragmatism and intimate arrangements: Online hook-up devices in gay life. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(4):496–511. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.930181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel Cristian J, Adam BD. Everyday moral reasoning in the governmentality of HIV risk. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2014;36(1):60–74. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Pope L. When do gain-framed health messages work better than fear appeals? Nutrition Reviews. 2015;73(1):4–11. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuu010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]