Abstract

Background

Caregivers experiencing depression or caring for people experiencing depression are at risk of high burden. This systematic review examined the effect of non-pharmacological interventions for caregivers that (a) target improving caregivers’ depressive symptoms, (b) help caregivers manage the depressive symptoms of the person for whom they provide care, or (c) both (a) and (b).

Methods

Eligible trials published between January 1, 1985, and May 30, 2019 were retrieved from five electronic databases. The studies’ methodological quality was assessed against 15 criteria. Pooled effect sizes (ESs) were calculated, and heterogeneity assessed using the Higgin’s I2 statistic. Meta-regressions were also conducted to identify significant moderators (participant sub-group analyses) and mediators (identify how the interventions worked).

Results

Sixteen studies evaluating 18 interventions were included for review. These studies included a total of 2178 participants (mean = 94, SD = 129.18, range 25–518). The most common condition (n = 10/16) of the care recipient was dementia. The average methodological score was in the moderate range (8.76/15). Interventions had a moderate effect on caregivers’ depression in the short term (ES = − 0.62, 95% CI − 0.81, − 0.44), but the effect dissipated over time (ES = − 0.19; 95% CI − 0.29, − 0.09). A similar pattern was noted for anxiety. The moderator analysis was not significant, and of the mediators examined, significant ones were self-management skills of taking action, problem solving, and decision-making.

Discussion

Non-pharmacological interventions are associated with improvement of depression and anxiety in caregivers, particularly in the short term. The main recommendation for future interventions is to include the self-management skills taking action, problem-solving, and decision-making. Enhancing the effect of these interventions will need to be the focus of future studies, particularly examining the impact of booster sessions. More research is needed on non-dementia caregiving and dyadic approaches.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-06891-6.

KEY WORDS: caregivers, anxiety, depression, chronic disease, patient-centered care, self-management

BACKGROUND

Approximately 50 million caregivers in North America provide care to a family member or friend for issues related to chronic illness, disability, or aging.1, 2 The annual economic value of caregivers’ unpaid care (on average 10–30 h per week3–5) is estimated to be $450 billion in the USA and at least $26 billion in Canada.6, 7 With the confluence of increasing life expectancy, an aging population, and increasing prevalence of chronic illness, the need for caregivers continues to grow4 and supporting caregivers in maintaining their critical roles is imperative.

Although caregivers may feel rewarded by the experience,3, 7 they nonetheless develop psychological or mental health symptoms from the challenges and additional roles imposed on them.4, 8, 9 It is estimated that between 30 and 70% of caregivers experience clinically significant symptoms of depression and approximately 10–25% meet the diagnostic criteria of major depression.4, 8–10 The impact of depression is significant and is associated with reduced physical health, psychiatric morbidity, and reduced quality of life, which may all lead to lower quality of caregiving.11, 12

Caregivers caring for someone experiencing depressive symptoms are a particularly vulnerable sub-group, reporting increased time spent caregiving, increased caregiver burden, and worse caregiver mental health symptoms (potentially persisting for years) as compared to those caring for someone who is not depressed.13–17 This is in line with studies demonstrating a bidirectional relationship between care recipients’ and caregivers’ depression; those caring for someone who is depressed are more likely to be depressed themselves, and vice versa.18, 19 Therefore, interventions are not only needed to help caregivers manage their own depression, but also to support them in managing the care recipient’s depressive symptoms. The aim of this systematic review was to examine the effect of non-pharmacological interventions for caregivers that (a) target improving caregivers’ depressive symptoms, (b) help caregivers manage the depressive symptoms of the person for whom they provide care, or (c) both (a) and (b).

METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) was followed,20 and the review was prospectively registered (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42018100397).

Criteria for Considering Studies

Types of Studies

Eligible studies were published (or in-press) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental trials published between January 1, 1985, and May 30, 2019, where a group of adult caregivers received an intervention designed to help them manage their own depressive symptoms and/or the depressive symptoms of the adult for whom they provide care. Eligible studies had to report comparative data to evaluate the difference(s) between the control and intervention groups; however, all types of control groups were eligible, including usual care.

Types of Participants

Caregivers were defined as a family member, spouse, adult child, friend, or any other significant person involved in providing unpaid assistance to an individual requiring care. Care recipients were anyone needing assistance from a caregiver due to aging or a chronic, physical condition or neurocognitive disorder and reporting co-morbid mild depressive symptoms. Care recipients with a mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) or advanced or palliative disease were excluded as the needs of these groups differ and in the case of advanced disease grief and bereavement play a role.21–23

To be included, the caregiver and/or the care recipient had to report at least mild depressive symptoms at baseline according to the following instruments (sample mean rounded to the nearest integer):

Beck Depression Inventory (scores ≥ 10)24

Beck Depression Inventory-II (scores ≥ 13)25

Centre for Epidemiological Studies – Depression 20 items (scores ≥ 16)26, 27

Centre for Epidemiological Studies – Depression 10 items (scores ≥ 10)28

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale – Depression subscale (scores ≥ 8)29

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Depression (scores ≥ 8)30

Patient Health Questionnaire (scores ≥ 5)31

Geriatric Depression Scale (scores ≥ 11)32

If an instrument measuring a similar concept, such as burden or distress, was used for screening potential participants, the study was included if the sample mean baseline depressive symptoms was reported and met the threshold for mild depressive symptomatology.

Types of Interventions

Non-pharmacological interventions that employed cognitive, physical, emotional, and/or social strategies to reduce depressive symptoms were eligible. The intervention could be administered to the caregiver alone or to the care recipient-caregiver dyad, as long as the focus remained on the caregiver. Interventions including a pharmacological component were excluded; however, if the participants received medication as part of usual care (either intervention or control group), the study was not excluded.

Types of Outcomes

The primary outcome was caregivers’ depressive symptoms. Secondary outcomes were not determined a priori and all outcomes reported in at least three studies at one time point were considered.

Search Methods

The development of the search strategies was in consultation with an academic librarian. Eligible studies were first identified through a comprehensive electronic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the Cochrane Library. French or English studies published since 1985 were selected. The search strategy used a combination of keywords and medical subject heading terms targeting the following: (a) caregiver (e.g., caregiver(s), carer, caretaker(s), friend(s)); (b) depression (e.g., depression, depressive disorder); (c) interventions (e.g., exercise, self-help, counseling, psychological); and (d) study design (e.g., control groups, experimental design). The complete search for one database is included in Appendix A. Retrieved studies were downloaded to EndNote and screened using Rayyan, a mobile web application. Secondary search strategies included: (a) verifying the reference lists of relevant reviews and manuscripts retrieved; (b) contacting researchers who conduct work in this area; (c) using the “find similar” function in PubMed; and (d) manually searching relevant journals.

Data Collection

Selection of Studies

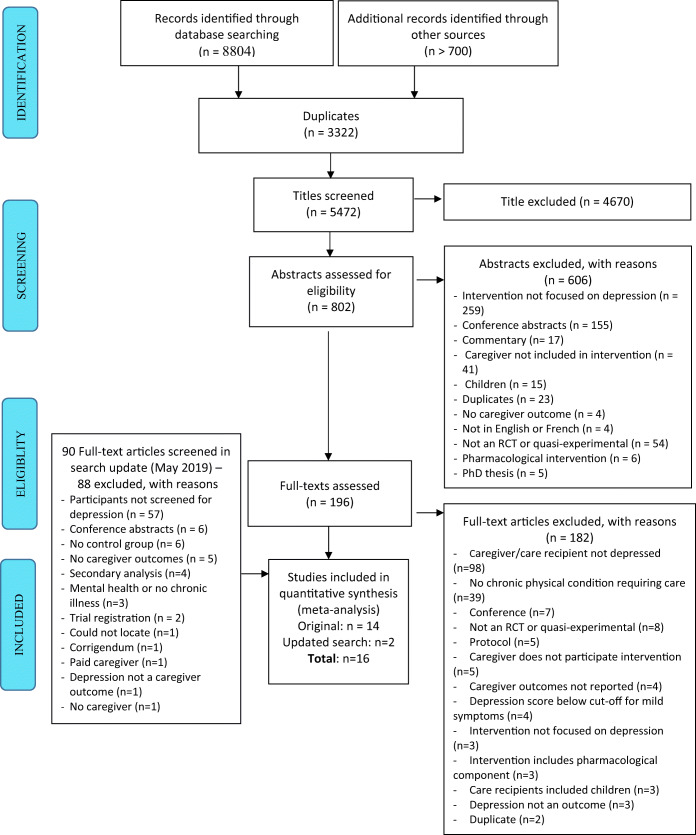

The original search was run in February 2017, and two trained research assistants (RAs) assessed the eligibility of retrieved titles and abstracts. Full texts of eligible citations were then obtained, and their reference lists were examined to identify additional studies. The inclusion/exclusion of full texts was confirmed by two authors, and discrepancies were discussed at regular team meetings to reach consensus. The search was updated in May 2019 (see Fig. 1), where one RA screened titles and abstracts and an additional RA confirmed the eligibility of the full texts identified.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a standardized Excel form based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,33 previously used by the team,34–36 and piloted on the first three studies. For the remaining studies, data were extracted by a trained RA and verified by at least one RA or other author. If some of the data were unclear, the authors of the original studies were contacted. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved at team meetings.

Data Items and Coding

The data extraction form documented the following: (a) reviewers’ names; (b) authors and year; (c) country; (d) study design; (e) type of control group; (f) aim(s); (g) theoretical framework; (h) population (age, sex, depression level, relationship, sample size); (i) confirmation of eligibility; (j) unit of allocation (caregiver versus care recipient-caregiver dyad); (k) setting, (l) sample size; (m) summary of the intervention and control groups; (n) intervention content; (o) delivery format (e.g., face-to-face, self-directed); (p) mode of delivery (e.g., face-to-face, self-directed); (q) provider; (r) intensity of the intervention37; (s) fidelity; (t) uptake rate; (u) primary and secondary outcomes; (v) timing of measurement; and (w) effect. If authors used more than one instrument to measure the same outcome, extracted data reported the instrument most often used across studies. If studies had more than one experimental arm, only those arms that met the inclusion criteria were included. The outcome data were categorized into three timeframes: T1, baseline to ≤ 3 months post-baseline; T2, > 3 post-baseline to < 12 months; and T3, ≥ 12 months post-baseline. If two data outcome points within the same timeframe were reported, the data closest to the mid-point of the timeframe was used.

In addition, 13 depression self-management skills were extracted from the included interventions: (a) decision-making, (b) problem-solving, (c) resource utilization, (d) partnership with healthcare professional, (e) taking action, (f) behavioral activation, (g) cognitive restructuring, (h) self-monitoring, (i) health habits, (j) communicating about depression, (k) social support, (l) relaxation activity, and (m) self-tailoring (see supplementary materials Appendix B)38–44 Interventions are often not labeled as self-management but included many of the key self-management skills shown to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms. Self-management is a recommended treatment for adults with mild to moderate depressive symptoms and as an adjunct to more intensive treatments for adults experiencing severe depressive symptoms.45

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by two trained RAs using a combination of criteria from the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool33 and CONSORT statement,46 and included (a) trial design, (b) inclusion criteria specified, (c) pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes, (d) psychometric properties of instruments provided, (e) power calculation explicit, (f) target sample size reached, (g) randomization method specified and truly random, (h) randomization allocation concealed, (i) outcome assessors blind to treatment allocation, (j) participants blind to treatment allocation, (k) interventionists blind to treatment allocation, (l) participant flow described, (m) intention-to-treat analysis used, (n) > 80% of sample in final analysis, and (o) reasons for withdrawal and/or attrition stated. Each item was scored as either positive (1) or negative (0). A total out of 15 was calculated for each study. Studies were considered to be of high methodological quality if at least 12 of the criteria were met, moderate quality if 7–11 of the criteria were met, and low if less than 7 criteria were met.47 If information was not reported or was ambiguous, attempts were made to contact the authors for clarification.

Data Analysis

A meta-analysis was performed by calculating a pooled Cohen’s d as well as a Cohen’s d for the outcomes at each time point. Cohen’s d is defined as the mean difference between the intervention and the control group divided by the pooled standard deviation.48 If a study utilized both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, the data from the per-protocol analysis was included in the meta-analysis. If a manuscript did not include all the data needed for the meta-analysis, attempts were made to contact the authors.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Higgin’s I2 statistic, a measure of inconsistency that describes the percentage of variation between studies above that expected by chance alone.49 An I2 of 0% reflects that all variability is consistent with sampling error rather than being due to true differences between studies. I2 values of 25% are categorized as low, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high heterogeneity.49 Fixed-effect models were conducted for I2 values lower than 25%, and random-effect models were conducted for I2 values higher than 25%.33

The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p < 0.05 and all tests were two-sided. STATA (version 15.1) was used to perform the analyses. Effect sizes (ESs) for the outcomes are reported in forest plots for each time point (T1–T3). If insufficient data were reported for inclusion in the meta-analysis, the manuscript was considered for descriptive review only. Egger’s test and funnel plots were computed for the primary outcome based on the first (T1) and second (T2) time point to examine potential publication bias.

The extent to which the pooled ESs for the primary outcome varied according to the following participant (moderators) and intervention (mediators) characteristics (mediators) was examined using meta-regression50: condition for which the care recipient required support, caregiver or dyad participated in the intervention, mode of delivery, intervention provider, individual or group intervention, total duration of the intervention, whether the intervention was tailored, and type and number of self-management skills included. To be included in the meta-regressions, characteristics needed to be included in at least 4 studies for each level of the variable.51 A p value < 0.05 was established to identify significant mediators.

RESULTS

Study Selection

See Figure 1 for details of the search strategy and reasons for exclusion. A total of 16 full texts were included in this review, 15 had sufficient data to be included in the meta-analysis, and the remaining one is reported descriptively only.52

Description of Studies

The 16 studies are described in Table 1. Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 9) with remaining studies from Europe (n = 4), and East Asia (n = 3). Most (n = 14) studies were two-group RCTs.

Table 1.

Descriptive Summary of Included Studies (N = 16)

| Author, year, country, QSA (/15) | Aim(s) | Caregiver demographics | Care recipient demographics | Intervention conditions and assessments | Outcome(s) [primary (p), secondary (s), unspecified (O)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver depressed | |||||

|

Belle et al., 2006 USA RCT (2 groups) QSA: 11 |

To evaluate the effect of a multicomponent intervention for caregivers to reduce depression and increase quality of life |

Info provided separated by race or ethnicity Hispanic or Latino (n = 168) Treatment group (n = 82) Mean age: 59.7 (SD = 14.3) % women: 80.5 % spouse: 43.9 Depression (CESD-10): 10.9 (SD = 7.2) Control group (n = 86) Mean age: 59 (SD = 13.6) % women: 83.7 % spouse: 39.5 Mean baseline depression score (CESD-10): 10.4 (SD = 7.3) White or Caucasian (n = 182) Treatment group (n = 96) Mean age: 63.5 (SD = 11.7) % women: 80.2 % spouse: 59.4 Depression (CESD-10): 9.5 (SD = 5.5) Control group (n = 86) Mean age: 63.2 (SD = 12.8) % women: 81.4 % spouse: 54.7 Mean baseline depression score (CESD-10): 10.6 (SD = 6.6) Black or African American (n = 168) Treatment group (n = 83) Mean age: 60.9 (SD = 12.9) % women: 84.3 % spouse: 31.3 Mean baseline depression score (CESD-10): 9.3 (SD = 6.2) Control group (n = 85) Mean age: 57.1 (SD = 12.8) % women: 88.2 % spouse: 28.2 Mean baseline depression score (CESD-10): 8.9 (SD = 6.0) |

Alzheimer’s or related disorder Hispanic or Latino (n = 168) Treatment group (n = 82) Mean age: 77.9 (SD = 9.3) % women: 65.9 Control group (n = 86) Mean age: 77.6 (SD = 9.9) % women: 64 White or Caucasian (n = 182) Treatment group (n = 96) Mean age: 77.5 (SD = 8.8) % women: 45.8 Control group (n = 86) Mean age: 78.6 (SD = 9.3) % women: 54.7 Black or African American (n = 168) Treatment group (n = 83) Mean age: 80.8 (SD = 8.6) % women: 68.7 Control group (n = 85) Mean age: 80 (SD = 8.5) % women: 61.2 |

T: intervention tailored to caregiver risk profiles. 12 individual sessions [9 in home (1.5 h each) + 3 phone sessions (30 min each)] + 5 group telephone support sessions (median 3.3 h each). Strategies included providing info, didactic instruction, role playing, problem-solving, skills training, and stress management C: caregivers mailed education materials + two < 15-min phone calls at 3 and 5 months Format: individual and group, face-to-face and telephone contact Provider: certified interventionists with at least a bachelor’s degree Total length of intervention: 858 min* Intervention duration: 6 months Timing of measures: 6 months post-baseline |

P: T2 = C for depression |

|

Blom et al., 2015 The Netherlands RCT (2 groups) QSA: 12 |

To evaluate the effect of an Internet self-help course “Mastery over Dementia” (MoD) designed to reduce caregiver depression and anxiety |

N = 251 (T = 151, C = 100) Mean age: T = 61.54 (SD = 11.93), C = 60.77 (SD = 13.07) % women: T = 69.8, C = 68.8 % spouse: T = 59.7, C = 56.3 Mean baseline depression score (CES-D 20 item): T = 17.89 (SD = 9.14), C = 16.61 (SD = 9.68) |

Dementia N = 245 (T = 149, C = 96) Mean age: T = 76.36 (SD = 9.45), C = 75.2 (SD = 9.32) % women: T = 61.1, C = 59.4 |

T: Internet course with 8 lessons, 1 booster session, and coach guidance and monitoring. Covered coping with behavioral problems, relaxation, arranging help, cognitive restructuring, and assertiveness training C: E-bulletins with practical information for dementia caregivers Format: individual Provider: guidance from coach (psychologist with training in CBT and experience in field of dementia) through electronic feedback Total length of intervention: n/a Intervention duration: 5 to 6 months Timing of measures: brief assessment after the 4th MoD lesson or E-bulletin (data not available) and 5–6 months post-baseline |

P: T2 = C for depression S: T2 = C for anxiety |

|

Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2015 USA RCT (2 groups) QSA: 7 |

To evaluate the effect of a Fotonovela which illustrates strategies to cope with stress and caregiving |

N = 110 (T = 55, C = 55) Mean age: T = 53.6 (SD = 10.76), C = 56.18 (SD = 11.18) % women: T = 85.5, C = 78.2 % spouse: T = 10.9, C = 10.9 Mean baseline depression scores (CES-D 20-item): T = 19.66 (SD = 11.85), C = 16.81 (SD = 13.74) |

Dementia or serious memory problems N = 110 (T = 55, C = 55) Mean age: T = 80.93 (SD = 9.16), C = 82.91 (SD = 8.15) |

T: 16-page Fotonovela picture book illustrating ways to cope with difficult behavior, manage stress, and ask for help from family members, access to one group meeting in which caregiver problems were discussed and information provided (offered to T and C group participants) C: usual information. Participants provided publicly available pamphlets about managing CG stress called: “Take Care of Yourself: 10 Ways To Be a Healthier Caregiver.” Optional group meeting (same as T group) Format: individual and self-directed (with one optional group meeting) Provider: primarily self-directed with optional group meeting lead by research assistants Total length of intervention: n/a Intervention duration: n/a Timing of measures: 4 and 6 months post-baseline |

O: T2 = C for depression |

|

Hou et al., 2014 Hong Kong RCT (2 groups) QSA: 12 |

To evaluate the feasibility and effect of a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program to improve mental health among caregivers |

N = 141 (T = 70, C = 71) Mean age: T = 57.9 (SD = 8.49), C = 57.08 (SD = 9.21) % women: T = 86.7, C = 80.6 % spouse: T = 37.1, C = 43.7 Mean baseline depression scores (Chinese Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-CES-D 20-item): T = 16.91 (SD = 8.97), C = 17.55 (SD = 8.92) |

Chronic illness or chronic condition |

T: 8 weekly 2-h sessions led by instructors and CD-guided daily home practice (instructed to do 30–45 min/day); covered body scan, meditation, yoga, and mindfulness C: self-help book with supportive information and health education Format: group class and individual home practice Provider: instructors had completed professional training in MBSR and had 3 years teaching experience in MBSR. Total length of intervention: 3060 min Intervention duration: 2 months Timing of measures: 2 and 5 months post-baseline |

P: T1 > C for depression (d = − 0.41) T2 > C for depression (d = − 0.36) S: T1 > C for anxiety (d = − 0.36) T2 = C for anxiety |

|

King et al., 2007 USA Single group with historically matched control group QSA: 5 |

To examine the effect and durability of a caregiver problem-solving intervention on caregiver and stroke survivor outcomes |

N = (completers) = 30 (T = 15, historically matched control = 15) Mean age: T = 62.3 (SD = 9.9), C = 62.7 (SD = 12.2) % women: T = 66.7, C = 60.0 % spouse: T = 93.3, C = 93.3 Mean baseline depression scores (CES-D 20-item): T = 19.3 (SD = 8.2), C = 19.6 (SD = 7.3) |

Stroke N = 30 (T = 15, C = 15) Mean age: T = 66.2 (SD = 10.8), C = 64.3 (SD = 10.1) % women: T = 42.6, C = 38.7 |

T = 10 guided sessions with manual (45–60 min each); covered problem-solving skills, CBT-based strategies (e.g., relaxation and reframing negative thoughts), stress management, self-care, and behavior management C: 15 matched controls who participated in a descriptive study of stroke CGs and survivors. Matched on CES-D scores, gender, age, race, and caregiving relationship; received usual care Format: individual; introduction and first 2–3 sessions conducted face-to-face; remaining 7–8 sessions conducted by telephone Provider: nurses Total length of intervention: 525 min Intervention duration: 2 to 2.5 months Timing of measures: 2 to 2.5 months and 4 to 4.5 months post-baseline; data for control group only available for 2 to 3 months post-baseline |

O: T1 > C for depression (d = − 0.80) |

|

King et al., 2012 USA RCT (2 groups) QSA: 8 |

To evaluate a caregiver problem- solving intervention designed to reduce and prevent negative outcomes during the first caregiving year |

N = 255 (T = 136, C = 119) Mean age: T = 54.5 (SD = 15.1), C = 54.6 (SD = 13.3) % women: T = 76.5, C = 80.7 % spouse: T = 61.8, C = 63.9 Mean baseline depression scores (CES-D 20-item): T = 23.4 (SD = 9.43), C = 22.64 (SD = 9.68) |

Stroke N = 248 (T = 136, C = 112) Mean age: T = 61.2 (SD = 14.6), C = 61.5 (SD = 14.7) % women: T = 42.6, C = 38.7 |

T: manual with 10 guided sessions (mean session duration 37 min); covered stress management, problem-solving skills, and coping with emotional responses; participants identified caregiving problems and developed problem-solving strategies C: waitlist control with 2 well-being check-ins (2nd and 5th month). After 6 months, option to have five 30-min telephone sessions with supportive listening with no problem solving or information giving Format: Individual; when possible, first two session done face-to-face, others via telephone Provider: nurse practitioner or advanced clinical psychology doctoral student Total length of intervention: 370 min Intervention duration: 3 to 4 months Timing of measures: 3 to 4 months, 6 months, and 12 months post-baseline |

O: T2 = C for depression and anxiety T3 = C for depression and anxiety |

|

Lavretsky et al., 2012 USA Pilot RCT (2 groups) QSA: 11 |

To evaluate the effect of Kundalini yoga and Kirtan Kriya meditation compared to passive relaxation with instrumental music to improve mental health and depression scores |

N = 39 (T = 23, C = 16) Mean age: T = 60.5 (SD = 28.2), C = 60.6 (SD = 12.5) % women: T = 100, C = 87 Mean baseline depression scores (HAM-D): T = 11.4 (SD = 4.0), C = 11.9 (SD = 4.1) |

Dementia |

T: daily yogic practice with ancient chanting meditation (Kirtan Kriya) for 8 weeks (12 min/day). Both T and C groups received psychoeducation about dementia and caregiver health. C: daily relaxation with instrumental music for 8 weeks (12 min/day); psychoeducation (see above) Format: individual; one face-to-face baseline visit; intervention self-directed Provider: self-directed Total length of intervention: n/a Intervention duration: 2 months Timing of measures: 2 months post-baseline or at early termination |

P: T1 = C |

|

López et al., 2007 Spain RCT (3 groups) QSA: 9 |

To compare the effect of two interventions [traditional weekly sessions (TT) and minimal therapist contact sessions (MTC)] to a waitlist control group in improving the emotional well-being of family caregivers |

Note: demographic data only presented for full sample N = 91 (T-MTC = 28, T-TT = 24, C = 39) Mean age: 53.9 (SD = 11.6) % women: 86.8 % spouse: 33.0 Mean baseline depression scores (BDI): T-MTC = 12.68 (SD = 7.31), T-TT = 17.29 (SD = 8.19), C = 14.23 (SD = 8.76) |

Physically disabled older adults Mean age: 77.3 (SD = 8.4) % dementia: 80.2 % women: 69.2 |

T-TT: eight 60-min weekly counseling sessions focused on learning cognitive-behavioral skills, diaphragmatic breathing, increasing pleasant activities, cognitive restructuring, problem-solving, and improving self-esteem; included written material and homework T-MTC: three 90-min sessions; between sessions, reading materials provided and three phone contacts; same CBT skills and similar schedule as the TT with less therapist contact C: waitlist control; no information or therapist contact provided Format: individual face-to-face and reading materials Provider: therapist Total length of intervention: 480 min (TT), 300 min (MCT) Intervention duration: 2 months Timing of measures: 2 months post-baseline |

O: TT-T1 > C for depression (d = − 1.13) and anxiety (d = − 1.21) MTC-T1 = C for depression‡ MTC-T1 > C for anxiety‡ |

|

Losada et al., 2012 Spain RCT (3 group) QSA: 10 |

To evaluate Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to improve symptoms of depression and anxiety in dementia caregivers |

N = 135 (T-CBT = 42, T-ACT = 45, C = 48)Mean age: T-CBT = 61.48 (SD = 12.4), T-ACT = 61.69 (15.31), C = 62.28 (SD = 12.92) % women: T-CBT = 90.5, T-ACT = 82.2, C = 81.02 % spouse: T-CBT = 31, T-ACT = 48.9, C = 41.7 Mean baseline depression scores (CES-D 20-item): T- CBT = 27.88 (SD = 1.49), T- ACT = 28.18 (SD = 1.44) C = 28.10 (SD = 1.39) |

Dementia |

T-CBT: 8 weekly sessions (about 90 min each); cognitive restructuring, assertive skills/asking for help, relaxation, and increasing pleasant activities T-ACT: 8 weekly sessions (about 90 min each); acceptance of aversive events and their causes, selecting courses of action consistent with personal values, and acting upon those decisions C: minimal support 2-h workshop with booklet and education about dementia Format: individual face-to-face Provider: clinical psychologists with master’s or doctoral preparation also trained in CBT and ACT principles and techniques Total length of intervention: 720 min (CBT), 720 min (ACT) Intervention duration: 2 months Timing of measures: 2 and 8 months post-baseline |

P: CBT T1 > C for depression (d = − 0.96) CBT T1 = C for anxiety CBT T2 > C for depression (d = − 0.77) CBT T2 = C for anxiety ACT T1 > C for depression and anxiety‡ ACT T2 = C for depression and anxiety‡ |

|

Nunez-Naveira et al., 2016 Denmark, Poland, and Spain Pilot RCT (2 groups) QSA: 6 |

To evaluate the impact of the understAID intervention on the psychological well-being of caregivers, to assess caregiver satisfaction with the intervention, and to test the technical and pedagogical specifications of the intervention |

N = 77 (T = 41, C = 36) Mean age: not specified % women: T = 58.1, C = 70 % spouse: not specified Mean baseline depression scores (CES-D 20-item): T = 19.4, SD = 9.03, C = (21.42, SD = 8.64) |

Dementia |

T: Internet application with 5 modules covering information about cognitive declines, daily tasks, behavioral changes, social activities, and coping with stress; daily task section to create a calendar schedule and a social network section allowing caregivers to interact with each other C: usual care; no access to the Internet application Format: individual; online Provider: self-directed; social network section of intervention moderated by researchers Total length of intervention: n/a Intervention duration: 3 months of self-directed use; frequency and duration of use not specified Timing of measures: 3 months post-baseline |

O: T1 = C for depression |

|

Pan & Chen, 2019 China RCT (2 groups) QSA: 11 |

To explore the effect of a cognitive-behavioral intervention on the depressive symptoms and coping strategies of family caregivers of people with dementia |

N = 112 (T = 56, C = 56) Mean age: T = 63.3 (SD = 11.2), C = 62.1 (SD = 10.6) % women: T = 55.4, C = 69.6 % spouse: T = 50.0, C = 46.4 Mean baseline depression scores (CES-D 10-item): T = 13.9 (SD = 3.5), C = 13.2 (SD = 3.1) |

Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or MMSE < 17) N = 112 (T = 56, C = 56) Mean age: T = 79.0 (SD = 9.4), C = 80.0 (9.8) % women: T = 71.4, C = 55.4 |

T: five-month (60-min) in-home cognitive-behavioral sessions and telephone consultations (20 to 30 min) aimed at receiving participant feedback and reinforcing content after each session; intervention included five modules all based on CBT principles C: five monthly (5- to 10-min) casual conversations about daily life and health with nurses at home, in hospital, or by telephone Format: individual, face-to-face, telephone Provider: nurses Total length of intervention: 425 min Intervention duration: 5 months Timing of measures: 5 and 7 months post-baseline |

O: T2 > C for depression (d = − 0.48) |

|

Steffen et al., 2016 USA RCT (2 groups) QSA: 8 |

To evaluate a telehealth intervention for emotionally distressed women caregivers of people with progressive neurocognitive disorders |

N = 74 (T = 33, C = 41) Mean age: all = 60.3 (SD = 10.8) % women: all = 100 % spouses: 52.2 Mean baseline depressive symptoms (BDI-II): T = 13.1 (SD = 8.0), C = 17.0 (SD = 8.8) |

Dementia or neurocognitive disorder N = 74 Mean age: All = 77.4 (SD = 9.4) |

T: behavioral coaching with workbook with strategies to manage care recipients’ behaviors, relaxation, self-efficacy, and behavioral activation; included 10 videos (30 min each), 10 weekly phone calls (30–50 min each), and 2 maintenance calls from a coach C: received a basic care guide on dementia and care challenges; caregivers received 7 bi-weekly phone calls (20 min each) to check on safety, provided suggestions based on guide, and answer questions Format: individual; video, booklet, telephone Provider: doctoral-level clinical psychologist and trained master’s-level clinicians Intervention duration: 3.5 months (14 weeks) Timing of measures: 3.5 months (14 weeks) and 9.5 months post-baseline |

P: T2 = C for depression and anxiety |

|

Tremont et al., 2015 USA RCT (2 groups) QSA: 13 |

To evaluate the effect of a telephone intervention to reduce depression, and burden in dementia caregivers |

N = 250 (T = 133, C = 117) Mean age: T = 63.32 (SD = 12.3), C = 62.03 (SD = 13.75) % women: T = 80, C = 76 % spouse: T = 51, C = 51 Mean baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D 20-item): T = 17.04 (SD = 11.7), C = 17.7 (SD = 11.7) |

Dementia N = 250 (T = 133, C = 117) Mean age: T = 79.22 (SD = 9.11), C = 76.74 (SD = 10.93) % women: T = 55, C = 57 |

T: 16 telephone calls (initial phone call ~ 60 min and follow-up calls 15 to 30 min) that covered dementia education, emotional support, coping strategies, health habits, psychoeducation to assist with problem solving; termination letter and package of education materials provided C: 16 telephone support calls with non-directive support (mean duration 30.1 min); package of educational materials provided Format: individual; initial screening face-to-face; primarily via telephone with some written materials Provider: master’s-level therapists with experience working with people with dementia and/or caregivers Total length of intervention: 397.5 min Intervention duration: 6 months Timing of measures: 6 months post-baseline |

P: T2 = C for depression |

|

Yoo et al., 2019 South Korea RCT (2 groups) QSA: 8 |

To evaluate the effect of a multicomponent therapeutic intervention program (I-CARE) on reducing burden in caregivers of people with dementia |

N = 38 (T = 19, C = 19) Mean age: T = 65.9 (SD = 13.4), C = 63.3 (SD = 13.3) % women: T = 73.7, C = 84.2 % spouse: T = 78.9, C = 57.9 Mean baseline depressive symptoms (GDS): T = 13.8 (SD = 6.0), C = 13.4 (SD = 8.7) |

Dementia |

T: four sessions (~ 60 min each); one group session on dementia education; three individual sessions of individual counseling focused on CBT, stress, and coping; one session on daily activities C: waitlist control Format: group and individual face-to-face sessions Provider: physician and psychologist Total length of intervention: 240 min Intervention duration: 8 to 10 weeks (2 to 2.5 months) Timing of measures: 2 to 2.5 months post-baseline |

P: T1 = C for depression |

| Care recipient depressed | |||||

|

Horton-Deutsch et al., 2002 USA Pilot quasi-experimental (2 groups non-randomized) QSA: 5 |

To evaluate the feasibility of implementing a multicomponent intervention to support family caregivers of elderly persons with depression |

N = 25 (T = 12, C = 13) Mean age: T = 67.6 (SD = 9.28), C = 67.1 (SD = 14) % women: T = 83.3, C = 61.5 % spouse: T = 58, C = 62 Mean baseline depression scores (CES-D 20-item): not specified |

Older adults with depression N = 25 (T = 12, C = 13) Mean age: T = 80.9 (SD = 7.79), C = 76.9 (SD = 6.5) % women: T = 33.3, C = 53.8 Mean baseline depression scores (GDS): not specified |

T: expanded home care services; average of 9 home visits (1 h 15 on average); in addition to standard home care, clinical profile and initial assessment, stressors, and resources of the family were identified, and the Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression framework was used to work through problems; caregiver and care recipient participate in the intervention C: individual standard home care (hours not specified) Format: face-to-face Provider: nurse Total length of intervention: 675 min Intervention duration: 2 months Timing of measures: 2-month baseline |

O: T1 = C for depression† |

| Caregiver or care recipient depressed | |||||

|

Smith et al., 2012 USA RCT (2 groups) QSA: 10 |

To evaluate the effect of a web-based psychoeducational intervention to support caregivers of stroke survivors with depression or reduce caregivers’ depression |

N = 32 (T = 15, C = 17) Mean age: T = 55.3 (SD = 6.9), C = 54.9 (SD = 12.9) % women: T = 100, C = 100 % spouse: T = 100, C = 100 Mean baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D 20-item): T = 21.7 (SD = 13.2), C = 17.7 (SD = 11.7) |

Stroke N = 32 (T = 15, C = 17) Mean age: T = 59.9 (SD = 8.2), C = 59.1 (SD = 13.6) All male spouses Mean baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D 20-item): T = 21.3 (SD = 12.9), C = 19.3 (SD = 13.4) |

T: Internet course that covered topics regarding feelings, understanding what it is like to be a care recipient, listening, coping with stress, non-verbal behavior; care recipient involved in some homework assignments C: access to resource room only and weekly caregiver tip; no guide beyond initial explanation of resource room; both T and C groups provided toll-free phone number in case technological problems were encountered or for medical emergency; halfway through both conditions, received a call from an RA to see if they had technical difficulties Format: online with emails and chat messages from professional coach; primarily individual with access to message boards and online chat Provider: PhD student in nursing Total length of intervention: n/a Intervention duration: 2.75 months (11 weeks) Timing of measures: 2.75 and 3.75 months post-baseline (11 and 15 weeks respectively) |

P: T1 > C for depression (d = − 0.82) T2 = C for depression |

Notes: Only depression and anxiety reported. T1, baseline to ≤ 3 months post-baseline; T2, > 3 post-baseline to < 12 months; and T3, ≥ 12 months post-baseline. T > C = treatment statistically significantly superior to control; T < C = control statistically significantly superior to treatment; T = C = no statistically significant differences between treatment and control. Effect size was calculated as the mean difference of the two study groups divided by the pooled standard deviation of the difference (Cohen, 1988)

CES-D Centre for Epidemiological Studies depression, GDS Geriatric Depression Scale, HAM-D Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, BDI-II Beck Depression Inventory-II, MMSE Mini Mental Status Examination, QSA quality score appraisal (scores out of 15)

*Length of the intervention was based on the mean or median number of minutes reported by authors. If only mean or median duration of individual sessions was reported, this was multiplied by the number of intervention sessions. If the range of individual sessions was provided (e.g., 15 to 30 min per session), the midpoint (e.g., 22.5) was multiplied by the number of sessions

†Data not available for meta-analysis. Results as reported by authors

‡In studies with 3 groups (2 treatment and 1 control), only one treatment group was included in the meta-analysis to ensure the independence of the control data (i.e., both treatment data are compared with the same control data). The outcome data from the intervention arm that most resembled the other included interventions was included in the meta-analysis. Findings from the second intervention arm are included as reported by the authors

Participants

Overall, the studies included a total of 2178 participants (mean = 94, SD = 129.18, range = 25–518); this included 2123 caregivers (51–66) and 57 care recipients.52, 66 Fourteen studies solely targeted the caregivers53–66 and two studies targeted the care recipient-caregiver dyad.52, 67 Samples often contained more women than men. The mean reported age of caregivers ranged from 54 to 68 years, and that for the care recipients from 60 to 83 years. The most common condition (n = 10/16; see Table 1) of the care recipient was dementia.

Type of Interventions

A total of 18 interventions were included (two studies evaluated more than one intervention).60, 61 Interventions are summarized in Table 1. Most interventions (n = 16) were delivered solely to the caregiver to help them manage their own depression.53–66 One intervention was delivered to the care recipient-caregiver dyad and aimed to support the caregivers in caring for older adults with depression.52 The remaining intervention was also delivered to the dyad and was the only one with the dual focus on assisting caregivers manage their own depression as well as supporting them in managing the care recipients’ depression.67

Interventions lasted between 2 and 6 months (n = 15, mean = 3.02 months).52–54, 56–67 The total number of minutes of the interventions range from 240 to 2170 (n = 13, mean = 717.04 min),52, 53, 56–61, 63–67 and the number of sessions ranged from 1 to 56 (n = 15, mean = 13.26 sessions).52–66

In terms of delivery format, 14 interventions used an individual format.52, 54, 57–65, 67 The remaining four interventions combined individual and group formats.53, 55, 56, 66 For the mode of delivery, three interventions were purely self-directed.55, 59, 62 The remaining 15 interventions were provider led and most commonly by a nurse52, 57, 58, 63 or psychologists.54, 61, 66 Of these 15 interventions, two were web-based,54, 67 five were delivered face-to-face,52, 56, 59, 61, 66 two were via telephone,64, 65 and four used combined face-to-face and telephone contacts.53, 57, 58, 63 Two were face-to-face and gave caregivers complementary written materials.65, 68

Most interventions52–55, 57, 58, 60, 62–67 focused on a combination of (a) stress management, (b) disease or symptom management, (c) management of behaviors of care recipients with neurological or cognitive disorders, and/or (d) emotional and affective management. Two interventions delivered conventional cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT),61, 66 and one intervention acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).61 Two interventions focused solely on the use of relaxation techniques (e.g., yoga, mindfulness).56, 59

Self-management skills were retrieved from 17 interventions (one did not have enough information62), with a mean of 4.29 self-management skills per intervention (SD = 4.18, range = 1–13). A summary of the self-management skills coded for each intervention is provided in Appendix B. The most frequently reported skills were relaxation,53, 54, 56–61, 63, 64, 67 cognitive restructuring,53–55, 57, 58, 60, 61, 63–66 behavioral activation,53, 57, 58, 60, 61, 63–67 developing social support,52–55, 57, 58, 60, 63, 65, 67 and resource utilization.52, 53, 55, 57, 58, 60, 64–67

Quality Assessment

The quality assessment summary score is included in Table 1 and detailed in Appendix C. The average quality assessment score was in the moderate range 8.76/15 (SD = 2.59, range = 5–13). Three studies54, 56, 65 were of high methodological quality.

Outcomes: Descriptive and Meta-analysis

Primary Outcome: Caregivers’ depression

An Egger’s test and funnel plots were computed and did not reveal publication bias at T1 (p = 0.323) or T2 (p = 0.116) (Appendix D). At T1, eight studies were included in the meta-analysis (see Fig. 2) and the pooled ES of − 0.62 (95% CI − 0.81, − 0.44) was statistically significant. There was no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.337). The largest ES at T1 was for a CBT intervention with minimal therapist contact60 at − 1.13 (95% CI − 1.67, − 0.58). At T2, the pooled ES for the 10 studies in the meta-analysis (see Fig. 2) was also statistically significant (− 0.19, 95% CI − 0.29, − 0.09) with no heterogeneity (p = 0.513). The largest ES at T2 was for a conventional CBT intervention.61 At T3, there was only one study58 and the ES was not significant = 0.13 (95% CI − 0.20, 0.45).

Figure 2.

Primary outcome: depression.

The only study not included in the meta-analysis52 was a pilot reporting no significant overall differences between the intervention and control groups.

Secondary Outcome

Over 30 secondary outcomes were extracted; however, based on our a priori criteria outlined in the methods, the only secondary outcome that qualified was anxiety. At T1, a significant pooled ES of − 0.65 (95% CI − 1.14, − 0.15) favoring the interventions was obtained (see Fig. 3). However, there was significant heterogeneity (I2 = 71.3%; p = 0.031). At T2, the pooled ES was also statistically significant (− 0.17, 95% CI − 0.32, − 0.01) with no heterogeneity (p = 0.458) (see Fig. 3). At T3, there was only the study58 and the ES was not significant at − 0.023 (95% CI − 0.348, 0.303).

Figure 3.

Secondary outcome: anxiety.

Moderator and Mediator Analyses for Intervention Characteristics

A summary of the moderator and mediator analyses is presented in Table 2. At T1, there were enough data to analyze two mediators (control group and mode of delivery); neither was significant. At T2, there were enough data to conduct a meta-regression on 17 mediators (see Table 2), and results were significant for three self-management skills: (a) taking action (yes/no) (p = 0.038); (b) problem-solving (yes/no) (p = 0.022); and (c) decision-making (yes/no) (p = 0.035).

Table 2.

Results by Mediator for Primary Outcome of Depression

| Mediator variables |

T1: post-intervention to ≤ 3 months (N = 8, unless not enough data for analysis) |

T2: >3 months to < 12 months (N = 10, unless not enough data for analysis) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of studies | Pooled ES | P value [95% CI] | I2 | # of studies | Pooled ES | P value [95% CI] | I2 | |

| Control group | ||||||||

| Active/therapeutic elements | 4 | − 0.57 | < 0.001 [− 0.82; − 0.33] | 15% | 5 | − 0.32 | 0.003 [− 0.52; − 0.11] | 0% |

| Non-active/therapeutic | 4 | − 0.70 | < 0.001 [− 1.00; − 0.41] | 24% | 5 | − 0.16 | 0.007 [− 0.27; − 0.04] | 0% |

| Disease type | ||||||||

| Dementia | 5 | − 0.62 | < 0.001 [− 0.88; − 0.35] | 0% | 8 | − 0.17 | 0.001 [− 0.28; − 0.07] | 0% |

| Other | 3 | − 0.74 | 0.002 [− 1.21; − 0.26] | 60% | 2 | − 0.37 | 0.018 [− 0.67; − 0.06] | 0% |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||||

| Included face-to-face contact | 4 | − 0.66 | < 0.001 [− 1.02; − 0.30] | 44% | 4 | − 0.19 | 0.004 [− 0.33; − 0.06] | 18% |

| Other (e.g., telephone, online) | 4 | − 0.66 | < 0.001 [− 0.95; − 0.36] | 0% | 6 | − 0.20 | 0.012 [− 0.35; − 0.04] | 0% |

| Provider | ||||||||

| Professional | 6 | − 0.72 | < 0.001 [− 0.98; − 0.45] | 27% | 8 | − 0.21 | 0.001 [− 0.34; − 0.08] | 11% |

| Self-directed | 2 | − 0.44 | 0.031 [− 0.84; − 0.04] | 0% | ||||

| Length of intervention (min)* | ||||||||

| 240–525 | 3 | − 0.81 | < 0.001 [− 1.24; − 0.39] | 25% | 3 | − 0.17 | 0.075 [− 0.35; 0.02] | 20% |

| 720–3060 | 3 | − 0.66 | 0.001 [− 1.03; − 0.28] | 39% | 4 | − 0.25 | 0.039 [− 0.49; − 0.01] | 41% |

| Number of sessions | ||||||||

| < 10 | 4 | − 0.71 | < 0.001 [− 1.08; − 0.34] | 55% | 4 | − 0.29 | 0.003 [− 0.47; − 0.10] | 17% |

| ≥ 10 | 3 | − 0.65 | < 0.001 [− 1.06; − 0.23] | 0% | 5 | − 0.15 | 0.020 [− 0.27; − 0.02] | 0% |

| Tailored intervention | ||||||||

| No | 3 | − 0.47 | 0.001 [− 0.74; − 0.19] | 0% | 4 | − 0.21 | 0.018 [− 0.38; − 0.04] | 0% |

| Yes | 5 | − 0.76 | < 0.001 [− 1.02; − 0.51] | 14% | 6 | − 0.19 | 0.003 [− 0.31; − 0.06] | 21% |

| Depression self-management skills | ||||||||

| Decision-making | ||||||||

| No | 5 | − 0.55 | < 0.001 [− 0.78, − 0.32] | 0% | 6 | − 0.30 | < 0.001 [− 0.46; − 0.15] | 0% |

| Yes | 2 | − 1.01 | < 0.001 [− 1.45; − 0.57] | 0% | 4 | − 0.12 | 0.070 [− 0.25; 0.01] | 0% |

| Problem-solving | ||||||||

| No | 5 | − 0.55 | < 0.001 [− 0.78; − 0.32] | 0% | 4 | − 0.37 | 0.001 [− 0.6; − 0.15] | 0% |

| Yes | 2 | − 1.01 | < 0.001 [− 1.45; − 0.57] | 0% | 6 | − 0.15 | 0.010 [− 0.26; − 0.04] | 0% |

| Resource utilization | ||||||||

| No | 3 | − 0.57 | 0.001 [− 0.92; − 0.23] | 36% | 4 | − 0.34 | 0.003 [− 0.56; − 0.12] | 28% |

| Yes | 4 | − 0.82 | < 0.001 [− 1.15; − 0.50] | 0% | 6 | − 0.14 | 0.023 [− 0.26; − 0.02] | 0% |

| Forming partnerships with HCPs | ||||||||

| No | 6 | − 0.67 | < 0.001 [− 0.94; − 0.40] | 32% | 7 | − 0.24 | < 0.001 [− 0.37; − 0.11] | 5% |

| Yes | 1 | 3 | − 0.14 | 0.077 [− 0.29; 0.02] | 0% | |||

| Taking action | ||||||||

| No | 5 | − 0.55 | < 0.001 [− 0.78; − 0.32] | 0% | 6 | − 0.30 | < 0.001 [− 0.46; − 0.15] | 0% |

| Yes | 2 | − 1.01 | < 0.001 [− 1.45; − 0.57] | 0% | 4 | − 0.12 | 0.070 [− 0.25; 0.01] | 0% |

| Behavioral activation | ||||||||

| No | 2 | − 0.41 | 0.006 [− 0.71; − 0.12] | 0% | 3 | − 0.23 | 0.011 [− 0.41; − 0.05] | 0% |

| Yes | 5 | − 0.86 | < 0.001 [− 1.14; − 0.58] | 0% | 7 | − 0.18 | 0.004 [− 0.30; − 0.06] | 14% |

| Cognitive restructuring | ||||||||

| No | 3 | − 0.47 | 0.001 [− 0.74; − 0.19] | 0% | 2 | − 0.37 | 0.018 [− 0.67; − 0.06] | 0% |

| Yes | 4 | − 0.87 | < 0.001 [− 1.17; − 0.57] | 0% | 8 | − 0.17 | 0.001 [− 0.28; − 0.07] | 0% |

| Self-monitoring | ||||||||

| No | 4 | − 0.59 | 0.001 [− 0.93; − 0.24] | 43% | 4 | − 0.27 | 0.002 [− 0.43; − 0.10] | 0% |

| Yes | 3 | − 0.88 | < 0.001 [− 1.26; − 0.51] | 0% | 6 | − 0.15 | 0.017 [− 0.29; − 0.04] | 1% |

| Health habits | ||||||||

| No | 6 | − 0.67 | < 0.001 [− 0.94; − 0.4] | 32% | 5 | − 0.24 | 0.004 [− 0.41; − 0.08] | 15% |

| Yes | 1 | 5 | − 0.17 | 0.010 [− 0.29; − 0.04] | 0% | |||

| Communicating about depression | ||||||||

| No | 5 | − 0.67 | < 0.001 [− 0.97; − 0.35] | 44% | 7 | − 0.24 | < 0.001 [− 0.37; − 0.11] | 5% |

| Yes | 2 | − 0.81 | 0.003 [− 1.34; − 0.27] | 0% | 3 | − 0.14 | 0.077 [− 0.29; 0.02] | 0% |

| Social support | ||||||||

| No | 4 | − 0.53 | < 0.001 [− 0.77; − 0.29] | 7% | 3 | − 0.34 | 0.085 [− 0.73; 0.05] | 46% |

| Yes | 3 | − 0.96 | < 0.001 [− 1.35; − 0.58] | 0% | 7 | − 0.17 | 0.002 [− 0.28; − 0.06] | 0% |

| Relaxation activities | ||||||||

| No | 2 | − 0.42 | 0.006 [− 0.75; − 0.08] | 0% | 2 | − 0.18 | 0.105 [− 0.40; 0.04] | 0% |

| Yes | 5 | − 0.86 | < 0.001 [− 1.14; − 0.58] | 0% | 8 | − 0.21 | 0.001[− 0.33; − 0.08] | 13% |

| Self-tailoring | ||||||||

| No | 2 | − 0.41 | 0.006 [− 0.17; − 0.12] | 0% | 5 | − 0.24 | 0.003 [− 0.40; − 0.08] | 0% |

| Yes | 5 | − 0.86 | < 0.001 [− 1.14; − 0.58] | 0% | 5 | − 0.16 | 0.012 [− 0.29; − 0.04] | 11% |

| Number of skills | ||||||||

| 1–3 | 2 | − 0.41 | 0.006 [− 0.71; − 0.12] | 0% | 2 | − 0.31 | 0.015 [− 0.56; − 0.06] | 0% |

| 4–6 | 2 | − 0.73 | 0.006 [− 1.25; − 0.21] | 37% | 3 | − 0.38 | 0.032 [− 0.73; − 0.03] | 50% |

| 7–13 | 3 | − 0.96 | < 0.001 [− 1.35; − 0.58] | 0% | 5 | − 0.13 | 0.049 [− 0.26; 0.00] | 0% |

Notes: Data in italics indicate significant results at p < 0.05. If I2 > 25%, then the random-effect model is used to compute the pooled effect size. I2 values of 25% are categorized as low, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high heterogeneity

ES effect size (Cohens’ d), I2 Higgin’s statistic measure of heterogeneity

*Length of the intervention was based on the mean or median number of minutes reported by authors. If only the mean or median duration of individual sessions is reported, this was multiplied by the number of intervention sessions. If the range of individual sessions was provided (e.g., 15 to 30 min per session), the midpoint (e.g., 22.5) was multiplied by the number of sessions

DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review to critically appraise the effect of interventions either aimed at reducing caregivers’ depression or helping the caregiver manage the care recipient’s depression. Sixteen studies were reviewed. Meta-analyses techniques were conducted for the primary outcome (depression) and a secondary outcome (anxiety). An examination of a moderator and several mediators on the effects of non-pharmacological interventions was also conducted. The key findings are as follows: (a) interventions were successful in reducing caregivers’ depression and anxiety, (b) but the effect reduced over time, and (c) the significant mediators were the self-management skills taking action, problem-solving, and decision-making.

The non-pharmacological interventions reviewed were successful in reducing caregivers’ depression. This is consistent with previous meta-analyses on the effects of “generic” caregiver interventions in lowering depression and anxiety (as the main psychological symptoms among caregivers).37, 69 However, the ESs for both depression and anxiety in the present meta-analysis were in the small to moderate range in comparison to mostly small ESs in previous meta-analyses.37, 69 Typically, generic caregiver interventions provide a range of information and coping skills training to help caregivers feel better equipped to manage the challenges of their role, which in turn might result in lowering depression and anxiety.37, 69 Generic interventions are often offered regardless of caregivers’ baseline emotional well-being. However, the present meta-analysis suggests that targeted caregiver interventions might be more efficacious than generic ones. This conclusion is further supported by Sheard and Maguire70 reporting ESs of 0.85 and 0.94 for anxiety and depression, respectively, when interventions included patients who screened positive for these symptoms, which is in comparison to ESs of 0.33 for anxiety and 0.16 for depression among non-screened patients.

Although in the present meta-analysis ESs were significant post-intervention, the longer-term effects were less pronounced. Thus, to increase the durability of intervention effects, booster or maintenance sessions might be needed. Intervention boosters are typically contacts that are beyond the main intervention, are shorter in duration than the initial intervention, and are designed to reinforce key content from the initial intervention.71 Only one RCT in the present meta-analysis included a booster session54; however, the final outcome measurement was performed prior to the booster, precluding any conclusions about its impact. Tolan et al.72 found that families who received a booster intervention following a family-focused prevention program reported sustained benefits. Evidence in the physical activity literature also supports the use of boosters to achieve sustained behavior outcomes.71

In terms of active components of the interventions, three self-management skills (taking action, problem-solving, and decision-making) were identified as significant mediators for the primary outcome of depression. These findings align with previous studies40 emphasizing that learning self-management skills enhances self-efficacy, ultimately resulting in changes in health behaviors and health status. However, there is increasing evidence that not all self-management skills are equally efficacious. For instance, a systematic review by Schaffler et al.73 suggested that self-management interventions were more efficacious when these included problem-solving, taking action, and resource utilization. Our analyses further provide support for including problem-solving and taking action in future interventions.

Unfortunately, the sample size was too small to examine a number of mediators and much remains unknown about the optimal components of this kind of intervention. Many studies included caregivers of care recipients with dementia, and future studies need to examine the impact of these interventions among other caregiver sub-groups. Most interventions were delivered to the caregiver alone, and it is not known whether there is an advantage to including the care recipient-caregiver as a dyad. A previous systematic review74 by our team showed that dyadic caregiver interventions are more efficacious than caregiver-only intervention. Also, none of the studies reviewed included physical activity, despite the extensive literature on the efficacy of physical activity for depression75 and one review finding that physical activity interventions can significantly decrease caregivers’s distress and increase their well-being, quality of life, and sleep quality.76

Limitations of this review include missing details on the study design. We often did not receive responses from authors asking for more information. For all studies, no in-depth information was provided on medication type (e.g., anti-depressor, anxiolytic, etc.) and dosage for intervention and control groups. Also, this review focused on interventions that included a component relevant to mood/depression and it is recognized that interventions focused on broader issues of caregiver well-being (e.g., burden, communications skills) were most likely excluded from this review. Also, there was significant heterogeneity for the pooled ES of anxiety post-intervention, and no further investigation of the specific source was conducted due to the small number of studies. However, all studies were associated with a significant improvement of anxiety baseline post-intervention and were based on similar interventions. As 10/16 studies were focused on caregivers of patients with dementia, the generalizability of the findings might be limited to this caregiver sub-group.

CONCLUSION

Non-pharmacological interventions are associated with improvement of depression and anxiety in caregivers, particularly in the short term. The main recommendation for future interventions is to include the three key self-management skills of problem-solving, taking action, and decision-making. Extending the effects of these interventions will need to be the focus of future studies, particularly examining the impact of booster sessions. Other aspects of these interventions still need evidence, including whether a dyadic focus has advantages. Also, examining the effect of these interventions among caregivers other than those with dementia should be the focus of future studies.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 58 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fonds de la recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQ-S), Réseau de recherche en interventions en sciences infirmières du Québec (RRISIQ), and a CIHR Canada Research Chair.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sibalija J, Savundranayagam MY, Orange JB, Kloseck M. Social support, social participation, & depression among caregivers and non-caregivers in Canada: a population health perspective. Aging & Mental Health. 2020;24(5):765–73. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1544223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollica MA, Smith AW, Kent EE. Caregiving tasks and unmet supportive care needs of family caregivers: A U.S. population-based study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2020;103(3):626–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP. Caregiving in the U.S. Bethesda, MD; 2015.

- 4.Turcotte M. Family caregiving: What are the consequences? 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Family Caregiver Alliance 2016;Pages. Accessed at National Centre on Caregiver at https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver-statistics-demographics on September 24th 2019.

- 6.Feinberg L, Reinhard S, Houser A, Choula R. Valuing the Invaluable: 2011 Update The Growing Contributions and Costs of Family Caregiving. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2011:1-28.

- 7.Sinha M. Portrait of caregivers, 2012. In: Canada S, ed; 2013.

- 8.Family Caregiver Alliance 2018;Pages. Accessed at National Centre on Caregiving at https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver-depression-silent-health-crisis on December 14 2018.

- 9.Loh AZ, Tan JS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms Among Caregivers of Stroke Survivors. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2017;18(2):111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert SD, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C, Stacey F. Walking a mile in their shoes: anxiety and depression among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors at 6 and 12 months post-diagnosis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21(1):75–85. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller LS, Lewis MS, Williamson GM, Lance CE, Dooley WK, Schulz R, et al. Caregiver cognitive status and potentially harmful caregiver behavior. Aging and Mental Health. 2006;10(2):125–33. doi: 10.1080/13607860500310500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert S, Girgis A, Descallar J, Levesque JV, Jones B. Trajectories of mental and physical functioning among spouse caregivers of cancer survivors over the first five years following the diagnosis. Patient Education and Counseling. 2017;100(6):1213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(2):250–67. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langa KM, Valenstein MA, Fendrick AM, Kabeto MU, Vijan S. Extent and cost of informal caregiving for older Americans with symptoms of depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(5):857–63. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCusker J, Latimer E, Cole M, Ciampi A, Sewitch M. Major depression among medically ill elders contributes to sustained poor mental health in their informal caregivers. Age Ageing. 2007;36(4):400–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah AJ, Wadoo O, Latoo J. Psychological Distress in Carers of People with Mental Disorders. British Journal of Medical Practitioners. 2010;3(3):a327. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert SD, Jones BL, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Distressed Partners and Caregivers Do Not Recover Easily: Adjustment Trajectories Among Partners and Caregivers of Cancer Survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;44(2):225–35. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in Couples Coping With Cancer: A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review of Role and Gender Effects. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(1):1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Seminars in oncology nursing. 2012;28(4):236–45. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Group. TP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan J-Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliative Care. 2018;17(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moghaddam N, Coxon H, Nabarro S, Hardy B, Cox K. Unmet care needs in people living with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016;24(8):3609–22. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waller A, Girgis A, Johnson C, Lecathelinais C, Sibbritt D, Forstner D, et al. Improving outcomes for people with progressive cancer: interrupted time series trial of a needs assessment intervention. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2012;43(3):569–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8(1):77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, Alonso J. Screening for Depression in the General Population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 1983;67(6):361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins J, Green S. Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1. 0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011; [cited 2020 September 15]. 5:252-8. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current

- 34.Beatty L, Lambert S. A systematic review of internet-based self-help therapeutic interventions to improve distress and disease-control among adults with chronic health conditions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(4):609–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert SD, Harrison JD, Smith E, Bonevski B, Carey M, Lawsin C, et al. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: A systematic review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2012;2(3):224–30. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambert SD, Beatty L, Levesque JV, McElduff P, Turner J, Jacobsen J, et al. Evaluations of written self-directed psychosocial interventions to improve psychosocial and physical outcomes among adults with chronic health conditions: A meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(Suppl. 2):73. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodaty H, Green A, Koschera A. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(5):657–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Grieken RA, Kirkenier ACE, Koeter MWJ, Schene AH. Helpful self-management strategies to cope with enduring depression from the patients' point of view: a concept map study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:331. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0331-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Grieken RA, Kirkenier AC, Koeter MW, Nabitz UW, Schene AH. Patients' perspective on self-management in the recovery from depression. Health Expectations. 2015;18(5):1339–48. doi: 10.1111/hex.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bilsker D, Goldner EM, Anderson E. Supported self-management: a simple, effective way to improve depression care. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;57(4):203–9. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bilsker D, Paterson R. Antidepressant skills workbook. Vancouver, BC: Simon Fraser University; 2005.

- 43.Houle J, Gascon-Depatie M, Bélanger-Dumontier G, Cardinal C. Depression self-management support: a systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;91(3):271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From Theory to Intervention: Mapping Theoretically Derived Behavioural Determinants to Behaviour Change Techniques. Applied Psychology. 2008;57(4):660–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patten SB, Kennedy SH, Lam RW, O'Donovan C, Filteau MJ, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. I. Classification, burden and principles of management. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. International Journal of Surgery. 2012;10(1):28–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lambert S, Duncan LR, Kapellas S, Bruson A-M, Myrand M, Santa Mina D, et al. A Descriptive Systematic Review of Physical Activity Interventions for Caregivers: Effects on Caregivers’ and Care Recipients’ Psychosocial Outcomes, Physical Activity Levels, and Physical Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;50(6):907-19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

- 49.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring Inconsistency In Meta-Analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context. 2nd edn ed. London: BMJ Publishing; 2001.

- 51.Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, Shamliyan T, Sedrakyan A, Wilt TJ, et al. Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(11):1187–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horton-Deutsch SL, Farran CJ, Choi EE, Fogg L. The PLUS Intervention: a pilot test with caregivers of depressed older adults. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2002;16(2):61–71. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2002.32108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Life of Dementia Caregivers from Different Ethnic or Racial Groups. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(10):727–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blom MM, Zarit SH, Groot Zwaaftink RB, Cuijpers P, Pot AM. Effectiveness of an Internet intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: results of a randomized controlled trial. PloS One. 2015;10(2):e0116622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gallagher-Thompson D, Tzuang M, Hinton L, Alvarez P, Rengifo J, Valverde I, et al. Effectiveness of a Fotonovela for Reducing Depression and Stress in Latino Dementia Family Caregivers. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2015:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Hou RJ, Wong SY, Yip BH, Hung AT, Lo HH, Chan PH, et al. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the mental health of family caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2014;83(1):45–53. doi: 10.1159/000353278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.King R, Hartke R, Denby F. Problem-Solving Early Intervention: A Pilot Study of Stroke Caregivers. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2007;32(2):68–76. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.King R, Hartke R, Houle T, Lee J, Herring G, Alexander-Peterson B, et al. A problem-solving early intervention for stroke caregivers: one year follow-up. Rehabilitation nursing : the official journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses. 2012;37(5):231–43. doi: 10.1002/rnj.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lavretsky H, Epel ES, Siddarth P, Nazarian N, Cyr NS, Khalsa DS, et al. A pilot study of yogic meditation for family dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms: effects on mental health, cognition, and telomerase activity. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):57–65. doi: 10.1002/gps.3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.López J, Crespo M, Zarit SH. Assessment of the efficacy of a stress management program for informal caregivers of dependent older adults. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(2):205–14. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Losada A, Márquez-González M, Romero-Moreno R, Mausbach BT, López J, Fernández-Fernández V, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for dementia family caregivers with significant depressive symptoms: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(4):760–72. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Núñez-Naveira L, Alonso-Búa B, C. L, Gregersen R, Maibom K, Mojs E, et al. UnderstAID, an ICT Platform to Help Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. BioMed Research International; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Pan Y, Chen R, Yang D. The Role of Mutuality and Coping in a Nurse-Led Cognitive Behavioral Intervention on Depressive Symptoms Among Dementia Caregivers. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2019;12(1):44–55. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20181212-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steffen AM, Gant JR. A telehealth behavioral coaching intervention for neurocognitive disorder family carers Telehealth behavioral coaching for carers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;31(2):195–203. doi: 10.1002/gps.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tremont G, Davis JD, Papandonatos GD, Ott BR, Fortinsky RH, Gozalo P, et al. Psychosocial telephone intervention for dementia caregivers: A randomized, controlled trial. Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2015;11(5):541–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoo R, Yeom J, Kim GH, Park HK, Jeong JH, Kang Y, et al. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of a therapeutic intervention program for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of Clinical Neurology (Korea). 2020;15(2):235–42. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith G, Egbert N, Dellman-Jenkins M, Nanna K, Palmieri PA. Reducing depression in stroke survivors and their informal caregivers: a randomized clinical trial of a Web-based intervention. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2012;57(3):196–206. doi: 10.1037/a0029587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lopez J, Crespo M, Zarit SH. Assessment of the efficacy of a stress management program for informal caregivers of dependent older adults. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(2):205–14. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2010;60(5):317–39. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheard T, Maguire P. The effect of psychological interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: results of two meta-analyses. British Journal of Cancer. 1999;80(11):1770–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fjeldsoe B, Neuhaus M, Winkler E, Eakin E. Systematic Review of Maintenance of Behavior Change Following Physical Activity and Dietary Interventions. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2011;30:99–109. doi: 10.1037/a0021974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry D, Schoeny M. The Benefits of Booster Interventions: Evidence from a Family-Focused Prevention Program. Prevention Science. 2009;10(4):287–97. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schaffler J, Leung K, Tremblay S, Merdsoy L, Belzile E, Lambrou A, et al. The Effectiveness of self-management interventions for individuals with low health literacy and/or low income: A descriptive systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2018;33(4):510–23. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4265-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Regan T, Lambert SD, Girgis A, Kelly B, Turner J, Kayser K. Do couple-based interventions make a difference for couples affected by cancer? A systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:279. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bridle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, Atherton NM, Lamb SE. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;201(3):180–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]