INTRODUCTION

Metformin is the consensus first-line medication for type 2 diabetes mellitus.1 However, metformin was until recently contraindicated in patients with even modestly elevated serum creatinine (corresponding roughly to an estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) due to concerns that metformin may increase the risk of lactic acidosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD).2 On April 8, 2016, in response to two citizen petitions summarizing evidence that metformin is safe in mild-to-moderate CKD, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revised the label to permit providers to initiate metformin at eGFR levels of ≥ 45 and continue metformin as long as eGFR remains above 30 mL/min/1.73 m 2. We sought to assess whether metformin utilization in patients with CKD increased after the FDA label change.

METHODS

We used four consecutive National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) datasets, from 2011 through 2018, to assess trends in metformin use in patients with reduced eGFR.3 The primary analysis included patients with self-reported diabetes, glycosylated hemoglobin ≥ 6.5%, or both. Secondary analyses limited the cohort to patients taking non-insulin diabetes drugs in order to exclude patients with type 1 diabetes, for whom metformin is not indicated. eGFR was calculated using the CKDEpi formula, and the population was divided into four eGFR strata: ≥ 60, 45–59, 30–44, and < 30 mL/min/1.73 m[[2 4. Demographics, major comorbidities, and the proportion of patients taking metformin in each eGFR group were calculated using R 4.0.0 statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), including use of the “survey” package to account for NHANES weighted data.5

RESULTS

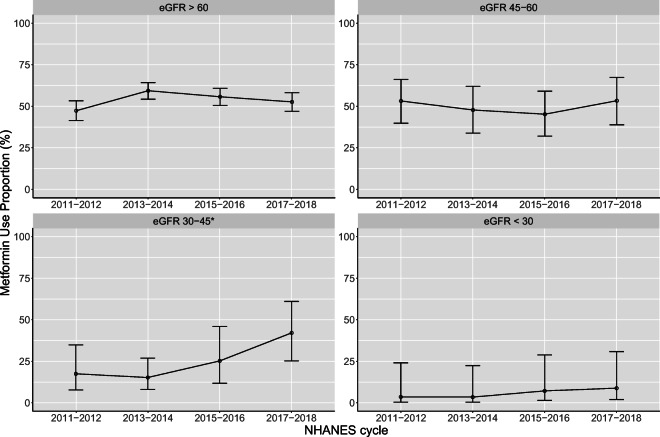

The eligible population in NHANES in each 2-year cycle ranged from 779 to 984 individuals (representing between 23.6 and 32.3 million people after weighting). Weighted population characteristics were similar across the study periods, although the number of individuals meeting inclusion criteria increased over time (Table 1). Lower eGFR was associated with less metformin use (P < 0.001; Fig. 1). No time trends in metformin use were noted except in the eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 group, in whom metformin use increased over time (P = 0.02) from 18% (95% CI, 7.7 to 35%) to 42% (95% CI, 25 to 61%). A numerical but not statistically significant increase in rates of metformin use was seen in the eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73-m2 group, from 3.6% (95% CI, 0 to 24%) to 8.8% (95% CI, 2.1 to 31%). Secondary analysis, restricted to patients taking non-insulin diabetes drugs, also showed a significant upward trend only in the eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73-m2 group, from 34% (95% CI, 15 to 61%) to 62% (95% CI, 38 to 81%) (P = 0.04).

Table 1.

Population Characteristics. First Row Presents Unweighted Sample Size; Second and Subsequent Rows Report Weighted Population Counts in 100,000s

| 2011–2012 | 2013–2014 | 2015–2016 | 2017–2018 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants (unweighted) | 779 | 823 | 927 | 984 | |

| N (weighted, in 100,000 s) | 236 | 269 | 294 | 323 | |

| Male sex | 121 (51) | 136 (51) | 161 (55) | 169 (52) | 0.66 |

| Age | 0.21 | ||||

| < 30 | 7 (3) | 5 (2) | 12 (4) | 11 (3) | |

| 30–49 | 57 (24) | 64 (24) | 64 (22) | 64 (20) | |

| 50–64 | 100 (42) | 108 (40) | 117 (40) | 122 (38) | |

| 65–74 | 41 (17) | 57 (21) | 65 (22) | 72 (22) | |

| > 74 | 31 (13) | 36 (13) | 36 (12) | 54 (17) | |

| Race | 0.08 | ||||

| Hispanic | 39 (17) | 41 (15) | 57 (19) | 48 (15) | |

| White | 132 (56) | 167 (62) | 164 (56) | 194 (60) | |

| Black | 41 (17) | 38 (14) | 43 (15) | 41 (13) | |

| Asian | 13 (6) | 17 (6) | 18 (6) | 21 (7) | |

| Other | 11 (5) | 7 (3) | 11 (4) | 18 (5) | |

| eGFR | 0.14 | ||||

| < 30 | 8 (3) | 9 (3) | 5 (2) | 7 (2) | |

| 30–44 | 12 (5) | 19 (7) | 13 (4) | 13 (4) | |

| 45–59 | 29 (12) | 27 (10) | 33 (11) | 34 (11) | |

| > 59 | 188 (79) | 214 (79) | 243 (83) | 269 (83) | |

| HbA1c | 0.28 | ||||

| < 6.5 | 82 (35) | 88 (33) | 102 (35) | 106 (33) | |

| 6.5–7.4 | 65 (28) | 85 (32) | 97 (33) | 119 (37) | |

| 7.5–8.9 | 49 (21) | 57 (21) | 56 (19) | 57 (18) | |

| > 8.9 | 39 (17) | 39 (15) | 39 (13) | 40 (12) | |

| Diabetes diagnosis | 191 (81) | 225 (84) | 249 (85) | 269 (83) | 0.52 |

| Heart failure | 23 (10) | 23 (8) | 21 (7) | 28 (9) | 0.56 |

| Liver disease | 18 (8) | 19 (7) | 30 (10) | 24 (7) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes drugs | |||||

| Metformin | 106 (45) | 143 (53) | 154 (52) | 166 (51) | 0.12 |

| Sulfonylurea | 68 (29) | 58 (22) | 59 (20) | 69 (21) | 0.02 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 16 (7) | 9 (3) | 9 (3) | 9 (3) | 0.02 |

| DPP4 inhibitor | 22 (9) | 22 (8) | 25 (8) | 31 (10) | 0.84 |

| GLP1 RA | 3 (1) | 11 (4) | 13 (4) | 5 (2) | 0.02 |

| SGLT2 I | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 7 (2) | 15 (5) | < 0.001 |

| Insulin | 57 (24) | 62 (23) | 67 (23) | 71 (22) | 0.87 |

DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; SGLT2, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2

Fig. 1.

Percentage of participants with diabetes mellitus or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% taking metformin by NHANES cycle and eGFR study group. *Statistically significant test for trend, P = 0.02. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2); HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

CONCLUSION

These data show an increase in metformin use in patients with eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 after the FDA label change. A suggestive finding of increased metformin use in the eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73-m2 group, although not statistically significant, raises safety concerns that deserve investigation.

NHANES data are aggregated into 2-year cycles and thus unable to show whether the beginning of the trend in the eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 group closely correlated with the FDA label change in April 2016. However, the timing of increased metformin use is consistent with the timing of the label change. The expected impact from the FDA label change for eGFR levels at 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 was not observed. Metformin use in this group was already close to the utilization seen at eGFR levels ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, which may explain the lack of change.

It is important to note that while NHANES data are weighted to represent the whole US population, the actual sample is small, especially in the lowest eGFR group. Further research is needed using larger datasets with more detailed temporal information and the ability to distinguish new from prevalent metformin use, a particularly relevant distinction as FDA guidelines differ for initiation versus continuation of metformin.

Nonetheless, these findings are relevant to diabetes care. Metformin use at lower eGFR levels appears to be rising, particularly at eGFR levels 30–44 and possibly at eGFR levels < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. It has been important to disseminate the knowledge that metformin is safe in relatively mild CKD, and the observed increase in metformin use at eGFR 30–44 likely represents improved care, aligned with FDA recommendations. But providers should be aware that metformin remains contraindicated at eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Alvin Mushlin, SciM, MD, for the helpful comments on the manuscript. Editorial support in the preparation of the manuscript was provided by Crystal Tran, BS, on behalf of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Editorial Service.

Funding

This study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (CER-2017C3-9230). This study was also supported in part by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) awarded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748).

Data Availability

Dataset is available from Dr. James Flory (e-mail: floryj@mskcc.org) through written agreement with the authors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclaimer

The funding sources had no involvement in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the decision to approve publication of the completed manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S90–S102. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipska KJ, Flory JH, Hennessy S, Inzucchi SE. Citizen Petition to the US Food and Drug Administration to Change Prescribing Guidelines: The Metformin Experience. Circulation. 2016;134(18):1405–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Continuous NHANES. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Accessed at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/ on 15 May 2020.

- 4.Matsushita K, Selvin E, Bash LD, Astor BC, Coresh J. Risk implications of the new CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation compared with the MDRD Study equation for estimated GFR: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(4):648–59. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Analytics Guidelines, 2011-2014 and 2015-2016. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. Accessed at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/analyticguidelines/11-16-analytic-guidelines.pdf on 1 June 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available from Dr. James Flory (e-mail: floryj@mskcc.org) through written agreement with the authors.