Abstract

Background

Discussing life expectancy helps inform decisions related to preventive medication, screening, and personal care planning. Our aim was to systematically review the literature on patient preferences for discussing life expectancy and to identify predictors for these preferences.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and gray literature from inception until 17 February 2021. Two authors screened titles/abstracts and full texts, and extracted data and one author assessed quality. The outcome of interest was the proportion of patients willing to discuss life expectancy. We reported descriptive statistics, performed a narrative synthesis, and explored sub-groups of patients according to patient characteristics.

Results

A total of 41 studies with an accumulated population of 27,570 participants were included, comprising quantitative survey/questionnaire studies (n=27) and qualitative interview studies (n=14). Willingness to discuss life expectancy ranged from 19 to 100% (median 61%, interquartile range (IQR) 50–73) across studies, with the majority (77%) reporting more than half of subjects willing to discuss. There was considerable heterogeneity in willingness to discuss life expectancy, even between studies from patients with similar ages, diseases, and cultural profiles. The highest variability in willingness to discuss was found among patients with cancer (range 19–100%, median 61%, IQR 51–81) and patients aged 50–64 years (range 19–97%, median 61%, IQR 45–87). This made it impossible to determine predictors for willingness to discuss life expectancy.

Discussion

Most patients are willing to discuss life expectancy; however, a substantial proportion is not. Heterogeneity and variability in preferences make it challenging to identify clear predictors of willingness to discuss. Variability in preferences may to some extent be influenced by age, disease, and cultural differences. These findings highlight the individual and complex nature in which patients approach this topic and stress the importance of clinicians considering eliciting patient’s individual preferences when initiating discussions about life expectancy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-06973-5.

KEY WORDS: life expectancy, patient preferences, communication

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between a patient’s life expectancy and future treatment, screening, and diagnostic decisions is an important consideration during individual care planning. Estimating the potential remaining years of life is particularly relevant for those with a limited estimated life expectancy, such as older people with frailty.1–4 Many screening and treatment guidelines differ, based on life expectancy.5,6 For example, less intensive diabetic treatment targets are recommended for people with a life expectancy of <10 years.5 Discussing life expectancy allows patients to make informed choices about their care.

Despite this, healthcare professionals may be reluctant to initiate discussions about life expectancy, as they may fear patient reactions to the topic, feel they are taking away hope, or want to respect cultural values of individual patients.7–9 Several studies have explored patient preferences for discussing life expectancy with widely varying results. For example, two studies among patients with cancer reported a willingness to discuss life expectancy of 19%10 and 81%,11 respectively. Previously published systematic reviews have primarily focused on patients with cancer.12–14

The aim of our systematic review was to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on patient preferences for discussing life expectancy and to identify predictors for willingness to discuss life expectancy.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.15 Our population of interest was individuals aged ≥18 years. We included studies regardless of patient group. We were interested in studies which reported on patient preferences, views, and attitudes toward discussing life expectancy. Our outcome of interest was the proportion of patients willing to discuss life expectancy with a healthcare provider. Studies were included regardless of their aim; that is, they only had to report a proportion of patients being willing to discuss life expectancy. Further, all study designs (that is, quantitative and qualitative) were included. Studies that solely considered the perspective of those other than patients, for example relatives and family, were excluded.

Search Strategy

We searched the databases PubMed, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycInfo from inception to February 17, 2021. We combined keywords for the following concepts: (1) “discussion, communication, decision making”; (2) “life expectancy”; and (3) “preferences, opinion, view, perspective, attitude, belief.” Non-English studies were translated and assessed for eligibility.16 The full search strategies are outlined in Appendix 1. Reference lists of eligible studies were also manually searched while a gray literature search was preformed using Google Scholar and the Turning Research Into Practice database.

Screening

Titles and abstracts were first screened independently by two authors (E. B. and W. T./C. L.). Full texts of relevant studies from the first step were then screened by two authors (E. B. and W. T./C. L.). Any disagreements were resolved via group discussion among these three authors.

Critical Appraisal

Two tools were used for critical appraisal of eligible studies. Quantitative survey/questionnaire studies were assessed using the checklist for Critical Appraisal of a Survey by Center for Evidence-Based Management.17 Interview studies with a qualitative study design were assessed using the Qualitative Checklist by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP).18 The full appraisals are reported in Appendix 2. Critical appraisal was performed by one author (E. B.). Uncertainties were resolved via group discussion with two other authors (W. T., C. L.).

Data Extraction

Two authors (E. B. and C. L.) extracted data on study characteristics and the outcome of interest from the eligible studies. For this review, every positive degree of willingness to discuss life expectancy was included. For example, if the question was “If you had advanced chronic illness, would you like to be informed about whether it is likely that you may not live more than a few months?”, responses such as “Yes, but only when I ask” and “Yes, it is the doctors duty to tell me even if I don’t ask” were both extracted as positive degrees of willingness to discuss.

Data Analysis

We attempted to conduct meta-analyses for all studies and pre-specified subgroups (in order to evaluate predictors of willingness to discuss life expectancy), planning to report pooled proportions through RStudios.19 We were interested in the following sub-groups: patient type, geographical location, age profile, and study design. We encountered high heterogeneity for analyses of both the overall group of studies and sub-groups (I2>90%); we therefore instead reported descriptive statistics only and conducted a narrative synthesis of the results. Studies were synthesized by comparing and interpreting extracted data to group similar studies together based on the sub-groups identified above.

RESULTS

Our search returned a total of 6,762 titles and abstracts, leaving 4,312 studies eligible for screening after removal of duplicates. We screened 224 full-text studies. A total of 41 studies (n=27,570 study participants) met the eligibility criteria. The PRISMA flowchart is presented in Figure 1. Three pairs of included studies20–25 reported on the same study data but only one dataset from each was included in the analyses. Characteristics of all included studies are presented in Table 1; however, a subset of studies20,23,25–34 were not included in calculating the range of proportions, median, or interquartile range (IQR) due to either not reporting a numeric proportion,26,27,31,32 being conducted among members of the public with no specific diagnosis,28,29,33 or reporting on a dataset already included.20,23,25 Two studies were excluded from the age analysis due to reporting age as an interval and not as mean/median age.30,34 One study was excluded from the sub-analysis of advanced cancer/non-advanced cancer35 (see details in Appendix 3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of review process.15

Table 1.

Descriptive Table Outlining Study Characteristics and Proportion Willing to Discuss Life Expectancy

| Author, country, year | Disease type | Mean/median age | Sample size | Proportion wanting to discuss life expectancy | Specific question about life expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with cancer | |||||

| Arbabi et al, Iran, 201443 | Mixed types of cancer | 43 years | 200 | 61% [agree] | Patients’ life expectancy should be discussed |

| Butow et al, Australia, 199645 | Breast and melanoma cancer | 48 yearsa | 144 | 57% [indicated wanting to discuss] | Patient preferences for discussing life expectancy |

| Clayton et al, Australia, 200526 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | 68 years | 19 | Most [most said it was every important to be informed that their illness would limit their lifespan but not all wanted to be told detailed information about their life expectancy] | Should palliative care doctors offer to discuss prognosis with you at certain times? |

| Deschepper et al, Belgium, 200831 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | N/R | 17 | Minority [a minority of the interviewed patients wanted all the information available about their medical situation and prognosis] |

Patient preferences regarding when and how they wanted to be informed. |

| Fujimori et al, Japan, 200744 | Mixed types of cancer | 62 years | 529 |

15% [strongly prefer] 36% [prefer] |

Telling about your life expectancy |

| Hagerty et al, Australia, 200411 | Advanced metastatic cancer | 63 years | 126b | 81%b [yes] | Patients indication on their preferences for prognostic information about the average length of time they would be likely to live |

| Hoesseini et al, The Netherlands, 202055 | Head and neck cancer | 65 years | 21 |

62% [very important] 38% [somewhat important] |

To what extent do you think it is important to receive information about your life expectancy? |

| Oskay-Özcelik et al, Germany , 201835 | Ovarian cancer | 58 years | 1830 |

65% [wished for as precise as possible] 22% [wished for an approximate estimation] |

Patient information needs concerning life expectancy |

| Mackenzie et al, Japan, 201849 | Mixed types of cancer | 64 years | 146c | 58%c [wanted to discuss life expectancy] | Patient preference for discussing life expectancy with radiation oncologist |

| Pardon et al, Belgium, 200920 and Pardon et al, Belgium 201121d | Advanced lung cancer | 64 years | 128d |

65%d [totally agree] 15%d [agree] 9%d [rather agree] |

I want to be informed about my life expectancy with the disease |

| Saracino et al, United States of America, 202152 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | 59 years | 206 |

43% [extremely] 29% [very] 13% [somewhat important] 9% [a little important] |

Participants stated importance to know about their cancer prognosis |

| Schofield et al, Australia, 200139 | Melanoma cancer | 58 years | 131 | 61% [yes] | Would you want information about how cancer would affect life expectancy? |

| Shen et al, United States of America, 201840 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | 56 years | 221 | 21% [yes] | If the doctor knew, would you want to know how long you have left to live? |

| Sherman et al, United States of America, 201832 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | 64 years | 13 | Varied [Patients varied widely in their perceptions. Some expressed a clear interest in detailed prognostic information. Others were more ambivalent] | Patients were asked about their preferences on information during prognosis |

| Tang et al, Taiwan, 200454 | Mixed types of cancer | 51 years | 364 | 30% [yes] | Would you want information about expected length of survival? |

| Uchida et al, Japan, 201938 | Mixed types of cancer | 63 years | 259e | 45%e [yes] | Would you like information from your doctor about your life expectancy? |

| Vehling et al, Germany, 201548 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | 67 years | 55 | 52% [indicating preference to discuss] | Patient preferences for discussing expected survival with a physician |

| Walczak et al, Australia, 201510 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | 63 years | 31 | 19% [clear interest] | Patient preferences indicating whether or not they wished to discuss life expectancy during consultations |

| Waller et al, Australia, 201924f | Mixed types of cancer | 65 years | 185f,g | 66%f,g [yes] | Would you want to discuss life expectancy with your doctor? |

| Waller et al, Australia, 202125f | Mixed types of cancer | 65 years | 302f | 59%f [preferred their doctor tell them their life expectancy as soon as they had the information] | Patients were asked about their preferred initiation source |

| Wright et al, United states of America, 201034 | Advanced mixed types of cancer | N/R | 301 | 73% [yes] | If your physician knew how long you had left to live, would you want him or her to tell you? |

| Zafar et al, Pakistan, 201650 | Mixed types of cancer | 49 years | 520h | 60%h [agreed] | I want my physician/nurse or another healthcare provider to discuss with me in detail how long people who have a disease like mine can expect to live. I want to know the average, the best case scenario, and the worst case scenario |

| Urological and surgical outpatients | |||||

| Clarke et al, United Kingdom, 200837 | Urological and surgical outpatients | 69 years | 120 | 58% [yes] | Would you want to know your predicted life expectancy if it were available in clinical practice? |

| Patients with heart disease | |||||

| Deng et al, United States of America, 201736 | Adult congenital heart disease | 33 years | 152 | 61% [yes] | Want information about life expectancy |

| O’Donnell et al, United States of America, 201851 | Advanced heart failure | 72 years | 50 | 66% [indicated wish to be informed] | Patient preference for being informed of a physician-anticipated life expectancy less than 1 year |

| Narayan et al, United States of America, 201758 | Heart failure | 57 years | 24 | 71% [acceptors] | Patient preferences for receiving survival estimates |

| Tobler et al, Switzerland, 201241 | Adult congenital heart disease | 35 years | 200 | 35% [endorsed wanting to know] | Patients endorsed wanting to know when they would die if someone could tell them that |

| First time nephrology outpatients | |||||

| Fine et al, Canada, 200542 | Nephrology outpatients | 64 years | 100 |

51% [absolute need to know] 46% [would like to know] |

Patient preferences for information on actual life expectancy on dialysis |

| Older patients | |||||

| Ahalt et al, United States of America, 201256 | Older adults with late-life disability receiving at home care | 78 years | 60 |

65%i [wanted information if their doctor believed they may have less than 5 years to live] 75%i [wanted information if their doctor believed they may have less than 1 year to live] |

Would participants want information when given a hypothetical scenario in which their doctor believed they may have less than 5 years/1 year to live? |

| Kistler et al, United States of America, 200622j | 70+ years adults living in continuing care retirement communities | 82 yearsk | 116j |

14%j [strongly agree] 52%j [agree] |

“I want my main doctor to talk to me about how long I might live” |

| Lewis et al, United States of America, 200623j | 70+ years adults living in continuing care retirement communities | 82 years | 116j | 52%j [agree] | “To help make cancer screening decisions, I want my doctor to talk with me about how long he/she thinks I might live” |

| Mathie et al, United Kingdom, 201227 | Care home residents | 88 years | 121 | Minority [majority of residents said they did not want to, even though some of the care homes were using care home-specific palliative care support tools, including advance care plans] | Residents were asked if they would like to talk to the staff about end-of-life |

| Schoenborn et al, United States of America, 201757 | Community-dwelling older adults | 76 years | 40 |

35% [wanted to discuss life expectancy if it were longer than 1 year] 33% [wanted to discuss life expectancy only toward the end of life] |

Older adults were asked whether they want to discuss life expectancy in the range of years with their primary care clinicians |

| Schoenborn et al, United States of America, 201846 | Older adults | 73 years | 878 | 41% [wanted to discuss] | Patients were asked if they were the hypothetical patient, whether they would like to discuss how long they may live with the doctor |

| Patients with Parkinson’s disease | |||||

| Tuck et al, United States of America, 201530 | Parkinson’s disease | N/R | 267 |

24% [at the time of the diagnosis] 14% [during the next few visits] 25% [only when the disease worsens] 24% [wait until I ask] |

When should your doctor discuss life expectancy? |

| Inpatients with mixed advanced disease | |||||

| Kai et al, Japan, 199347 | Mixed terminal disease | 68 years | 201 |

45% [candid information desired at all events] 5% [candid information desired if disease is curable] |

Patients’ preferences about candid information about diagnosis and prognosis |

| Waller et al, Australia, 202053 | Mixed advanced disease | 81 years | 186 | 23%l [no, but I would like to] | Has anyone talked to you about your life expectancy? |

| Members of the public with no specific diagnosis | |||||

| Cardona et al, Australia, 201929 | Members of the public | N/R | 497 |

24% [yes, but only when I ask] 68% [yes, it is the doctors duty to tell me even if I don’t ask] |

If you had advanced chronic illness, would you like to be informed about whether it is likely that you may not live more than a few months? |

| De Vleminck et al, Belgium, 201428 | Members of the public | N/R | n=9,651m |

77%m [yes, in principle always] 14%m [yes, only if I ask] |

Information preference of the studied population if they are faced with a life-limiting illness to know their life expectancy with the disease |

| Harding et al, United Kingdom, 201333 | Members of the public | 51 years | 9344 |

74% [always] 14% [if I ask] |

Patient preferences for wanting to know information on time left |

aButow 1996 reported the mean age at the time of diagnosis and not at time of enrolment in the study

bHagerty 2004 had varying proportions of patients answering the survey; 95% answered the life expectancy questioncMackenzie 2018 reported the proportion of patients that had not previously discussed life expectancy. This proportion is therefor based on the 127 patients that had not previously discussed life expectancy. A total of 17% had previously had the discussion

dPardon 2009 and Pardon 2011 are based on the same study and reported the same outcome and is therefore only represented once in the table

eUchida 2019 only had 226 patients (87.3%) completing the life expectancy section of the survey

fWaller 2019 and Waller 2021 are based on the same study population but reported different outcomes and is therefore presented twice in the table

gWaller 2019 reported the portion of patients that had not previously participated in discussion of life expectancy. This proportion is therefore based on the 130 patients that in total had not previously discussed life expectancy. Total of 29.7% had previously discussed their life expectancyh

iAhalt 2012 reported two different outcomes regarding preference for discussing life expectancy. Both are presented in the table, but only the 5 years willingness is part of the data analysis jKistler 2006 and Lewis 2006 are based on the same study, but reported different outcome, and is therefore presented twice in the table

kKistler 2006 reported age intervals instead of a mean/median age. The mean/median age from Lewis 2006 was copied since both studies reported on the same study populationlWaller 2020 reported the portion of patients that had not previously discussed life expectancy. This proportion is therefore based on the 154 patients that in total had not previously discussed life expectancy. A total of 9% had previously discussed their life expectancy

mDe Vleminck 2014 had 2,372 patients (24.6%) not answering the life expectancy section

N/R not reported

Characteristics of Included Studies

Two different study types were included: quantitative survey/questionnaire studies (n=27),11,22–25,28–30,33,35–52 including one baseline survey from a prospective randomized clinical trial,51 and qualitative interview studies (n=14),10,20,21,26,27,31,32,34,53–58 including one baseline interview from a prospective cohort study.34 Studies were predominantly from North America,22,23,30,32,34,36,40,42,46,51,52,56–58 Australia,10,11,24–26,29,39,45,53 and Western Europe,20,21,27,28,31,33,35,37,41,48,55 while five studies were from East Asia38,44,47,49,54 and two studies were from West Asia.43,50 A total of eight participant groups were represented: patients with cancer,10,11,20,21,24–26,31,32,34,35,38–40,43–45,48–50,52,54,55 surgical outpatients,37 patients with congenital heart disease,36,41,51,58 nephrology outpatients,42 older adults,22,23,27,46,56,57 patients with Parkinson’s disease,30 inpatients with mixed advanced diseases,47,53 and members of the public with no specific diagnosis.28,29,33 The age profile was predominantly older patients, while five studies reported on a study population with a mean/median age below 50 years.36,41,43,45,50 A table detailing characteristics of the included studies can be found in Appendix 4.

Willingness to Discuss Life Expectancy

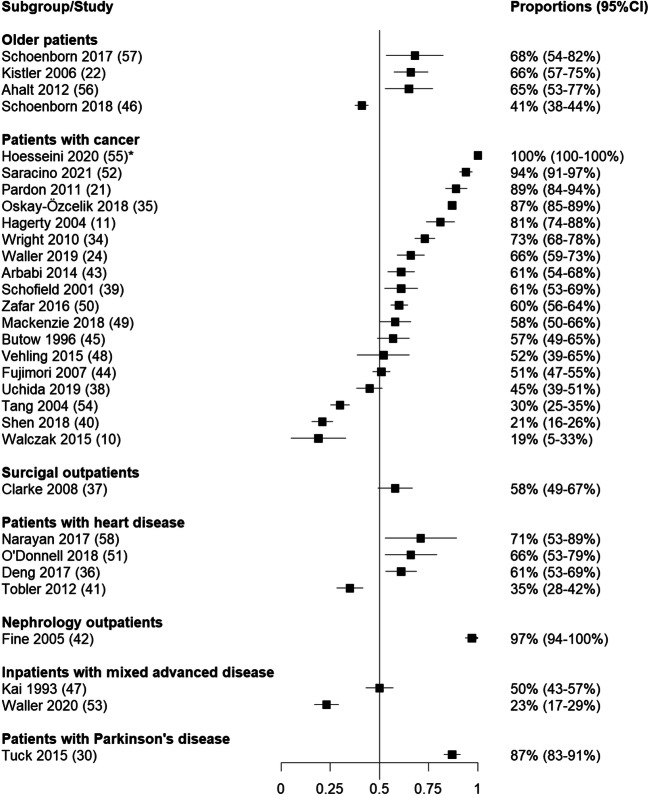

The proportions of patients willing to discuss life expectancy in each study are presented in Table 1 and Figure 2. Four studies reported a non-numeric proportion of participants willing to discuss life expectancy: Mathie et al. (2012)27 and Deschepper et al. (2008)31 reported the proportion willing to discuss life expectancy as “minority”, Sherman et al. (2018)32 reported the proportion as “varied” and Clayton et al. (2005)26 reported it as “most”. The remaining studies reported numeric proportions, which varied from 19 to 100% with a median of 61% (IQR 50–73). In total, 77% of numeric studies (n=24) reported a proportion willing to discuss life expectancy above 50%.

Figure 2.

Forest plot with all studies eligible for analyses in RStudios,19 depicting the overall heterogeneous distribution. The forest plot has a range from 0 to 1, correlating to proportions of willingness to discuss life expectancy between 0 and 100%. Studies to the left of the 0.5 axis (n=7) reported a willingness to discuss life expectancy below 50%, while studies to the right of the 0.5 axis (n=2) reported a willingness to discuss life expectancy 50% or above. *Hoesseini 2020 reported the proportion 100%, which equals a standard error of 0. To graphicly represent the study in this forest plot a simulated standard error of 1.0E-8 has been plotted.

Patient Type

Patients with cancer were the most frequently studied group (n=23). Among patients with cancer, the proportion willing to discuss life expectancy ranged from 19 to 100% (median 61%, IQR 51–81)10,11,21,24,26,31,32,34,35,38–40,43–45,48–50,52,54,55 including three non-numeric studies: “minority”,31 “varied”,32 and “most”26 (Fig. 3). Around one-fifth (22%) of the studies reported a proportion below 50%. In studies among patients with non-advanced cancer (n=10),24,38,39,43–45,49,50,54,55 20% of studies (n=2) reported a willingness below 50%, while in studies among patients with advanced cancer (n=10)10,11,21,26,31,32,34,40,48,52 two studies (20%) similarly reported a willingness below 50% (Appendix 5, eFigure 1). However, the advanced cancer group had a wider range (19–94%, median 73%, IQR 37–85), including the three non-numeric studies,26,31,32 compared to the non-advanced cancer group (30–100%, median 59%, IQR 51–61).

Figure 3.

Forest plots over sub-analysis based on patient type in RStudios.19 The forest plot has a range from 0 to 1, correlating to proportions of willingness to discuss life expectancy between 0 and 100%. Studies among patients with cancer (n=17) has four studies on the left of the 0.5 axis, meaning the willingness to discuss was below 50%. Studies among patients with heart disease (n=4) and older patients (n=4) each had one study to the left of the axis. Among studies with inpatients with mixed advanced disease (n=2), all studies were to the left or on the 0.5 axis. Studies conducted among surgical outpatients (n=1), patients with Parkinson’s disease (n=1), and nephrology outpatients (n=1) reported all studies to the right of the 0.5 axis. *Hoesseini 2020 reported the proportion 100%, which equals a standard error of 0. To graphicly represent the study in this forest plot a simulated standard error of 1.0E-8 has been plotted.

Other studied groups included patients with heart disease (n=4), older patients (n=5), surgical outpatients (n=1), Parkinson’s disease patients (n=1), nephrology clinic outpatients (n=1), and inpatients with mixed diseases (n=2). The proportion willing to discuss life expectancy among patients with heart disease (n=4) ranged from 35 to 71% (median 64%, IQR 48–69).41,36,51,58 Among older patients (n=5), the range was 41–68% (median 66%, IQR 53–67)46,22,27,56,57 including one non-numeric study where a “minority” was willing to discuss.27 Among surgical outpatients (n=1), the proportion was reported as 58%.37 The study conducted among patients with Parkinson’s disease (n=1) reported 87%30 of patients were willing to discuss life expectancy. Among first time outpatients at a nephrology clinic (n=1), a similar high proportion was reported: 97%.42 Among inpatients with mixed diseases (n=2), all studies reported a willingness to discuss at 50% or below: ranging from 23 to 50%.47,53

Geographical Location

The proportion willing to discuss life expectancy ranged from 21 to 97% (median 67%, IQR 63–80, Appendix 5, eFigure 2) 40,46,32,36,56,22,51,57,58,52,34,30,42 in North America (n=13) including one non-numeric proportion where the willingness “varied”;32 from 19 to 81% (median 59%, IQR 23–66)10,53,45,39,24,11,26 in Australia (n=8) including one non-numeric proportion where “most” were willing to discuss;26 from 35 to 100% (median 73%, IQR 52–89)21,27,31,35,37,41,48,55 in Western Europe (n=7) including two non-numeric proportions where a “minority” were willing to discuss;27,31 from 30 to 58% (median 50%, IQR 45–51)54,44,38,47,49 in East Asia (n=5); and 60 to 61% in West Asia (n=2).43,50 All locations had predominantly positive preferences for discussing life expectancy except East Asia, where almost half (40%) of the studies reported a proportion lower than 50%.

Age Profile

Among studies with a mean/median age of <50 years (n=5), the proportion of patients willing to discuss life expectancy ranged from 35 to 61% (median 60%, IQR 57–61, Appendix 5, eFigure 3).41,43,45,36,50 For studies with a mean/median age of 50–64 years (n=14), the proportion ranged from 19 to 97% (median 61%, IQR 45–87),10,40,54,38,32,44,49,39,58,52,11,21,42,35 including one non-numeric proportion where the willingness to discuss “varied”.32 For studies with an age profile of ≥65 years (n=13), the proportion willing to discuss life expectancy ranged from 23 to 100% (median 65%, IQR 51–66),22,24,26,27,37,46–48,51,53,55–57 including two non-numeric studies: in one study “most” were willing to discuss life expectancy 26 and in another a “minority” were.27 All age subgroups had similar trends, with one third or less of studies reporting a proportion below 50%. The studies in the lowest age subgroup (<50 years) and highest age subgroup (≥65 years), reported a proportion willing to discuss below 50% in around one-fifth (20%,17%) of the studies.41,46,53 One-third of the studies in the middle age group (50–64 years) reported a proportion below 50%.10,38,40,54

Study Design

Lastly, we analyzed studies based on study design (Appendix 5, eFigure 4). Studies with a quantitative study design (n=22), including one baseline survey from a prospective randomized clinical trail,51 reported the proportion of willingness to discuss life expectancy ranging from 21 to 97% (median 61%, IQR 51–66).11,22,24,30,35–52 The majority of the quantitative studies reported a proportion willing to discuss life expectancy above 50%. Among the qualitative studies (n=13), including one baseline interview from a prospective cohort study34 and four non-numeric studies (reporting different degrees of willingness to discuss: “minority”,27,31 ”varied”,32 and “most”26), the proportion willing to discuss life expectancy ranged from 19 to 100% (median 68%, IQR 30–73),10,21,26,27,31,32,34,53–58 with two-thirds reporting a proportion above 50% willingness to discuss life expectancy.

DISCUSSION

Willingness to discuss life expectancy varied widely. Most patients preferred to discuss life expectancy, with 77% of studies reporting the majority would be willing to discuss life expectancy. The variability in willingness to discuss life expectancy across studies highlights the complex interplay of the many factors (age group, patient type, geographical location, disease stage) that shape patient attitudes on this topic. Unfortunately, for providers, this complexity and variability, even among relatively homogenous patient populations, make it challenging to definitively identify predictors and patterns.

There may be several reasons why there was wide variability. Asian countries reported less willingness to discuss life expectancy among participants, with almost half (40%) studies reporting a willingness lower than 50%. Previous systematic reviews on preferences of East Asian patients with cancer found a similar outcome, with 30% willingness to discuss life expectancy.12,14 Being unaware of death is considered an important aspect of a good death, which could possibly explain this cultural trend.59,60 Participants from studies conducted in North America, Australia, West Asia, and Western Europe were generally positive toward discussing life expectancy, with most studies reporting proportions above 50%. There was no clear pattern with respect to age or patient type, despite wide variability. Another challenge in comparing proportions across studies is that the question and response options differed between studies (Appendix 6).

Previous reviews focused on advanced cancer and severe illness reported that patients generally tend to be less willing to discuss life expectancy as their disease progresses.14,61 In our review, however, we did not identify a clear pattern in the advanced cancer group, but we did find that all studies conducted among inpatients with mixed advanced diseases found that ≤50% of patients were willing to discuss their life expectancy. Like advanced cancer patients, we found large variability in studies of patients with non-advanced cancer. The large variability found in the two cancer groups is possibly due to patients with cancer being the most studied patient group. The general perception that a cancer diagnosis is a life-limiting diagnosis, no matter the disease progression,62,63 might explain the similar findings in these two groups.

Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included in this review. Previous literature has shown that the quality of data on life expectancy is influenced by the study method,64 with the willingness to disclose sensitive information possibly being lower when data is collected during face-to-face interviews and higher when using self-administrated surveys. This might result in an underestimation of otherwise positive attitudes to discussing life expectancy in qualitative studies. We found a slightly lower median willingness to discuss among qualitative studies (67%) than among quantitative studies (81%). It is also possible that physician type, physician characteristics, or the clinical setting may influence patient attitudes toward discussing life expectancy. We did not extract data on differences in attitudes related to who the patient would be having a discussion with. It may be that patients would feel more comfortable communicating about life expectancy with their general practitioner with whom they have a long-lasting and trusting relationship.65,66

Limitations

This review is limited by several factors. First, in the eligible studies, willingness to discuss life expectancy was explored under the conditions of a research study. Thus, the attitudes expressed may not reflect how patients would feel about discussing life expectancy in the context of actual clinical care (e.g., if the consideration was processed over time and considered with a trusted healthcare professional). Further, factors such as physician characteristics and the setting, which we did not capture, may affect how patients feel about these discussions. Second, while we report individual answer categories, we chose to combine every positive degree of willingness to discuss life expectancy to create one proportion, for example preferences such as “Yes, in principle always” and “Yes, only if I ask.” This may have led to an overestimation of the proportion in studies with multiple positive response options (n=13). Third, we included studies regardless of sample size, possibly introducing greater variance within the proportions. However, as we also calculated ranges excluding studies with less than 100 patients and found no significant changes, we kept all studies in the analyses (Appendix 7). Fourth, including qualitative studies likely introduced bias, because qualitative study samples are usually purposefully selected.67 Finally, included studies were very diverse in terms of framing of the question, study methods, and disease types, which resulted in high heterogeneity and made it difficult to compare results across studies. Specifically, the question about discussing life expectancy was framed in very different ways: some studies asked directly, other studies set up a hypothetical patient scenario, while studies also included different response options from one another. This made comparison between studies difficult (Appendix 6).

Clinical Implications

We could not identify any clear trends or predictors for patient preferences. As such, our findings stress the importance of considering every patient individually in terms of initiating discussions about life expectancy. While life expectancy is important to discuss for screening and treatment decisions in those with limited life expectancy, achieving a shared understanding around what and how much patients would like to know and discuss appears to be a good starting point during consultations that may deal with life expectancy. Despite its importance, it appears that clinicians cannot assume a willingness to discuss life expectancy based on specific characteristics, as people may have vastly different preferences regardless of similar, age, disease status, and culture. Preferences may change with age as health status changes and/or diseases progress. Therefore, clinicians should consider re-evaluating preferences around discussing life expectancy periodically and consider bringing it up when there may be a relevant reason to discuss it (e.g., at nursing home admission). Such discussions should incorporate the entire patient context (culture, health status, care preferences).

Implications for Future Research and Clinical Practice

This review highlights that preferences for discussing life expectancy cannot be easily summarized or generalized into precise guidance for clinical practice. Since the preferences for discussing life expectancy were generally positive but with large variations, future studies should explore mechanisms for determining patient preferences around how, if, and when to discuss life expectancy. Furthermore, research is needed with a focus on evaluating better integration of discussions into routine clinical practice, perhaps tools for electronic records that prompt discussion around preferences for discussing life expectancy or prompt re-evaluation of previous discussions in the transition of patients through health statuses. Similarly, more research is needed among patient types other than patients with cancer. Discussing life expectancy is important among all patients with limited life expectancy, despite the literature mainly focusing on patients with cancer.

CONCLUSION

The heterogeneity documented in this review underscores the highly individual and complex nature in which patients deal with life expectancy and thus the need to consider each patient individually. While most patients are positive toward discussing their life expectancy, there was variability across studies. Reasons for the wide variability may to some extent be due to geographical location, age, patient type, framing of the discussion, or even physician relationship. Variability and heterogeneity make it challenging to identify clear predictors of willingness to discuss life expectancy. Despite including all patient types, more than half of all studies were conducted among patients with cancer, highlighting the need for more studies examining life expectancy preferences among other patient groups. Future research should explore mechanisms for practically determining patient preferences for how, if, and when to discuss life expectancy, to be incorporated into existing guidelines, and ultimately into routine clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 842 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Anton Pottegård, University of Southern Denmark and Odense University Hospital, for helping with the conceptualization of the study and preparation of the manuscript. Further, we would like to acknowledge Lucas Morin, Clinical Investigation Unit, University Hospital of Besançon and High-Dimensional Biostatistics for Drug Safety and Genomics, Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Paris, for critical comments on the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bibbins-Domingo K. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Colorectal Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):836–845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho H, Klabunde CN, Yabroff KR, et al. Comorbidity-Adjusted Life Expectancy: A New Tool to Inform Recommendations for Optimal Screening Strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):667–676. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ouellet GM, Ouellet JA, Tinetti ME. Principle of rational prescribing and deprescribing in older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9(11):639–652. doi: 10.1177/2042098618791371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetes CCHFGSP. in IC for E with. Guidelines for Improving the Care of the Older Person with Diabetes Mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5s):265–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.51.5s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH, et al. Safety and Benefit of Discontinuing Statin Therapy in the Setting of Advanced. Life-Limiting Illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):691–700. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL, Cayea D, Pollack CE, Feeser S, Boyd C. Primary Care Practitioners’ Views on Incorporating Long-term Prognosis in the Care of Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):671–678. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack JW, Smith TJ. Reasons Why Physicians Do Not Have Discussions About Poor Prognosis, Why It Matters, and What Can Be Improved. J Clin Oncol. Published online September 22, 2016. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4564 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Thai JN, Walter LC, Eng C, Smith AK. “Every Patient is an Individual”: Clinicians Balance Individual Factors When Discussing Prognosis with Diverse Frail Elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):264–269. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walczak A, Henselmans I, Tattersall MHN, et al. A qualitative analysis of responses to a question prompt list and prognosis and end-of-life care discussion prompts delivered in a communication support program: Response to end-of-life QPL and discussion prompts. Psychooncology. 2015;24(3):287–293. doi: 10.1002/pon.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PA, et al. Cancer Patient Preferences for Communication of Prognosis in the Metastatic Setting. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1721–1730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimori M, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of Cancer Patients Regarding Communication of Bad News: A Systematic Literature Review. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39(4):201–216. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winner M, Wilson A, Ronnekleiv-Kelly S, Smith TJ, Pawlik TM. A Singular Hope: How the Discussion Around Cancer Surgery Sometimes Fails. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(1):31–37. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5564-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, Dimitry S, Tattersall MHN. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(7):1005–1053. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. The BMJ. 2009;339. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, et al. The Accuracy of Google Translate for Abstracting Data From Non-English-Language Trials for Systematic Reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(9):677–679. doi: 10.7326/M19-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Center for Evidence-Based Management. Critical Appraisal of a Survey. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Critical-Appraisal-Questions-for-a-Survey.pdf. Accessed 16 Jun 2020

- 18.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020

- 19.RStudio Team . RStudio: Integrated Development for R. PBC, Boston, MA: RStudio; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardon K, Deschepper R, Stichele RV, Bernheim J, Mortier F, Deliens L. Preferences of advanced lung cancer patients for patient-centred information and decision-making: A prospective multicentre study in 13 hospitals in Belgium. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(3):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pardon K, Deschepper R, Vander Stichele R, et al. Are patients’ preferences for information and participation in medical decision-making being met? Interview study with lung cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2011;25(1):62–70. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kistler CE, Lewis CL, Amick HR, Bynum DL, Walter LC, Watson LC. Older adults’ beliefs about physician-estimated life expectancy: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis CL, Kistler CE, Amick HR, et al. Older adults’ attitudes about continuing cancer screening later in life: a pilot study interviewing residents of two continuing care communities. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waller A, Turon H, Bryant J, Zucca A, Evans T-J, Sanson-Fisher R. Medical oncology outpatients’ preferences and experiences with advanced care planning: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waller A, Wall L, Mackenzie L, Brown SD, Tattersall MHN, Sanson-Fisher R. Preferences for life expectancy discussions following diagnosis with a life-threatening illness: a discrete choice experiment. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(1):417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, Tattersall MHN. Discussing life expectancy with terminally ill cancer patients and their carers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(9):733–742. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathie E, Goodman C, Crang C, et al. An uncertain future: The unchanging views of care home residents about living and dying. Palliat Med. 2012;26(5):734–743. doi: 10.1177/0269216311412233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Roelands M, et al. Information preferences of the general population when faced with life-limiting illness. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(3):532–538. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardona M, Lewis E, Shanmugam S, et al. Dissonance on perceptions of end-of-life needs between health-care providers and members of the public: Quantitative cross-sectional surveys. Australas J Ageing. 2019;38(3):e75–e84. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuck KK, Brod L, Nutt J, Fromme EK. Preferences of Patients With Parkinson’s Disease for Communication About Advanced Care Planning. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2015;32(1):68–77. doi: 10.1177/1049909113504241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deschepper R, Bernheim JL, Stichele RV, et al. Truth-telling at the end of life: A pilot study on the perspective of patients and professional caregivers. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(1):52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherman AC, Simonton-Atchley S, Mikeal CW, et al. Cancer patient perspectives regarding preparedness for end-of-life care: A qualitative study. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2018;36(4):454–469. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2018.1466845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harding R, Simms V, Calanzani N, et al. If you had less than a year to live, would you want to know? A seven-country European population survey of public preferences for disclosure of poor prognosis. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2298–2305. doi: 10.1002/pon.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright AA, Mack JW, Kritek PA, et al. Influence of Patients’ Preferences and Treatment Site on Cancer Patients’ End-of-Life Care. Cancer. 2010;116(19):4656–4663. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oskay-Özcelik G, Alavi S, Richter R, et al. Expression III: patients’ expectations and preferences regarding physician-patient relationship and clinical management-results of the international NOGGO/ENGOT-ov4-GCIG study in 1830 ovarian cancer patients from European countries. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2018;29(4):910–916. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng LX, Gleason LP, Khan AM, et al. Advance Care Planning in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: A Patient Priority. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.12.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clarke MG, Kennedy KP, MacDonagh RP. Discussing life expectancy with surgical patients: Do patients want to know and how should this information be delivered? BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida M, Sugie C, Yoshimura M, et al. Factors associated with a preference for disclosure of life expectancy information from physicians: a cross-sectional survey of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(12):4487–4495. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04716-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schofield PE, Beeney LJ, Thompson JF, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, Dunn SM. Hearing the bad news of a cancer diagnosis: The Australian melanoma patient’s perspective. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(3):365–371. doi: 10.1023/A:1011100524076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen MJ, Prigerson HG, Ratshikana-Moloko M, et al. Illness Understanding and End-of-Life Care Communication and Preferences for Patients With Advanced Cancer in South Africa. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–9. doi: 10.1200/JGO.17.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobler D, Greutmann M, Colman JM, Greutmann-Yantiri M, Librach SL, Kovacs AH. Knowledge of and Preference for Advance Care Planning by Adults With Congenital Heart Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(12):1797–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fine A, Fontaine B, Kraushar MM, Rich BR. Nephrologists Should Voluntarily Divulge Survival Data to Potential Dialysis Patients: A Questionnaire Study. Perit Dial Int J Int Soc Perit Dial. 2005;25(3):269–273. doi: 10.1177/089686080502500310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arbabi M, Rozdar A, Taher M, et al. Patients’ Preference to Hear Cancer Diagnosis. Iran J Psychiatry. 2014;9(1):8–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujimori M, Akechi T, Morita T, et al. Preferences of cancer patients regarding the disclosure of bad news. Psychooncology. 2007;16(6):573–581. doi: 10.1002/pon.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butow PN. When the diagnosis is cancer: Patient communication experiences and preferences. Published online 1996:8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Schoenborn NL, Janssen EM, Boyd C, et al. Older Adults’ Preferences for Discussing Long-Term Life Expectancy: Results From a National Survey. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):530–537. doi: 10.1370/afm.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kai I, Ohi G, Yano E, et al. Communication between patients and physicians about terminal care: a survey in Japan. Soc Sci Med. 1982;36(9):1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90235-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vehling S, Kamphausen A, Oechsle K, Hroch S, Bokemeyer C, Mehnert A. The Preference to Discuss Expected Survival Is Associated with Loss of Meaning and Purpose in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(11):970–976. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mackenzie LJ, Carey ML, Suzuki E, et al. Agreement between patients’ and radiation oncologists’ cancer diagnosis and prognosis perceptions: A cross sectional study in Japan. PloS One. 2018;13(6):e0198437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zafar W, Hafeez H, Jamshed A, Shah MA, Quader A, Yusuf MA. Preferences regarding disclosure of prognosis and end-of-life care: A survey of cancer patients with advanced disease in a lower-middle-income country. Palliat Med. 2016;30(7):661–673. doi: 10.1177/0269216315625810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Donnell AE, Schaefer KG, Stevenson LW, et al. Social Worker–Aided Palliative Care Intervention in High-risk Patients With Heart Failure (SWAP-HF): A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(6):516. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saracino RM, Polacek LC, Applebaum AJ, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Breitbart W. Health Information Preferences and Curability Beliefs Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waller A, Sanson-Fisher R, Nair BR, Evans T. Preferences for End-of-Life Care and Decision Making Among Older and Seriously Ill Inpatients: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(2):187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang ST, Lee S-YC. Cancer diagnosis and prognosis in Taiwan: Patient preferences versus experiences. Psychooncology. 2004;13(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/pon.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoesseini A, Dronkers EAC, Sewnaik A, Hardillo JAU, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Offerman MPJ. Head and neck cancer patients’ preferences for individualized prognostic information: a focus group study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):399. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6554-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahalt C, Walter LC, Yourman L, Eng C, Pérez-Stable EJ, Smith AK. “Knowing is better”: preferences of diverse older adults for discussing prognosis. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):568–575. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1933-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et al. Older Adults’ Preferences for When and How to Discuss Life Expectancy in Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(6):813–815. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.06.170067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Narayan M, Jones J, Portalupi LB, McIlvennan CK, Matlock DD, Allen LA. Patient Perspectives on Communication of Individualized Survival Estimates in Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2017;23(4):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Morita T, Hirai K, Uchitomi Y. Good death in cancer care: a nationwide quantitative study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(6):1090–1097. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chindaprasirt J, Wongtirawit N, Limpawattana P, et al. Perception of a “good death” in Thai patients with cancer and their relatives. Heliyon. 2019;5(7). doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A Systematic Review of Prognostic/End-of-Life Communication with Adults in the Advanced Stages of a Life-Limiting Illness: Patient/Caregiver Preferences for the Content, Style, and Timing of Information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robb KA, Simon AE, Miles A, Wardle J. Public perceptions of cancer: a qualitative study of the balance of positive and negative beliefs. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Jȩdrzejewski M, Thallinger C, Mrozik M, Kornek G, Zielinski C, Jassem J. Public Perception of Cancer Care in Poland and Austria. The Oncologist. 2015;20(1):28–36. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health. 2005;27(3):281–291. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Damarell RA, Morgan DD, Tieman JJ. General practitioner strategies for managing patients with multimorbidity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tarrant C, Stokes T, Baker R. Factors associated with patients’ trust in their general practitioner: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(495):798–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;24(1):9–18. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 842 kb)