Abstract

Depression amongst physicians can lead to poor individual and institutional outcomes. This study examined the prevalence and factors associated with depression and suicidal ideation amongst doctors in Hong Kong. Doctors who graduated from medical school at the University of Hong Kong between 1995 and 2014 were invited to participate in a survey measuring depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm, lifestyle behaviours, career satisfaction and socio-demographic characteristics. Data collection occurred between January and April 2016. The prevalence of screened-positive depression was 16.0% and 15.3% of respondents reported having suicidal ideation. Amongst those with positive depression screening scores, less than half reported having a diagnosed mood disorder. Sleeping fewer hours was associated with higher depression scores (P < 0.001) and an increased odds of meeting the cut-off for depression (P < 0.001). Factors associated with suicidal ideation included being unmarried (P = 0.012) and sleeping fewer hours (P = 0.022). Hong Kong doctors appear to have high rates of undiagnosed depression, and high levels of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideations. There is a need for greater awareness of the morbidity due to depression and to promote better mental health help-seeking among physicians. Barriers to mental health help-seeking need to be addressed and appropriate resources allocated to reduce suffering.

Subject terms: Health occupations, Risk factors, Health care, Health policy

Introduction

Depression is a common mental disorder. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) ranked it as the single largest contributor to global disability1. Studies have shown that people with depression are twice as likely to die prematurely due to any cause2 and have an increased risk for suicide3. WHO estimated the global prevalence of depression between 2.6 and 5.9% in 20154. In the workforce, depressed workers are at higher risks of absenteeism, performance deficits and unemployment5,6.

A systematic review of 46 physician population studies found that doctors experience higher rates of depression and suicide than the general population7. A meta-analysis of 54 studies estimated the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms amongst resident physicians to be 28.8%8, much higher than the WHO global estimate. Like other people with depression, depression in physicians can have a huge impact on their well-being and work performance. Depression has been associated with increased medical errors, decreased ability to handle work-related stress, increased absenteeism, discontinuation of medical training, disruption in personal lives, suicide, and poor quality of life7,9. A systematic review of resident physicians found that poor physical health, an unhappy childhood, and stress at work were related to depression. However, factors such as work hours, sleep deprivation, gender, social supports and marital status were not consistent with some studies indicating relationships and others not7. Studies have found that specialty choice may affect the risk of depression10 and there are strong associations between depression and alcoholism11,12, smoking13,14, and profession dissatisfaction15.

Studies suggest that Chinese physicians have higher rates of depression than the general population. The general population prevalence of depressive symptoms in China has been estimated to range from 31 to 47%16, whereas the prevalence in physicians is reported to range between 28.13 and 65.3%14,17,18. A study of 2641 physicians in China found that poor self-reported physical health, lengthy working hours, frequent night shifts and lack of regular physical exercise were related to more anxiety and depressive symptoms17. In Hong Kong (HK) the population prevalence for depression has been reported to range from 1.5 to 10.7%19,20. Although there have been studies examining burnout21,22 and stress23 in HK doctors, estimates for depression in HK doctors has only been studied among first-year interns where 35.8% of respondents demonstrated abnormal levels of depression as measured by the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale23.

Thoughts of suicide or harming oneself can occur when a person has depression and may be related to more severe forms of depression24. In a 2019 meta-analysis of 25 studies, the standardized mortality rate for suicides among physicians was calculated to be 1.44 (95% CI 1.1.6–1.72, I2 = 93.9%) with an overall prevalence of 1.0% for suicide attempts and 17% for suicidal ideation25. In 2012, a study of HK physicians reported that of the 226 physicians sampled, none had attempted suicide but 4.9% reported having suicidal ideations21, which is higher than the prevalence of 3.5% as observed in a general HK population study20. In China, an analysis of 18 physicians who committed suicide from 2004 to 2017 found that work stress and patient-doctor disputes were the most common reasons doctors committed suicide26.

Health and psychosocial factors have been shown to be related to retirement intentions of physicians27 and to date, these issues have not been explored in existing HK physician manpower surveys28.

With a skilled and healthy workforce being the foundation of a robust health care system, local data on the mental health of doctors would provide insight into a poorly investigated area that has implications on both patient care and physician well-being.

Aims

The aims of this study were to examine the epidemiology of depression and suicidal ideation among HK doctors.

Specific objectives

To examine the prevalence of depression and suicidal ideations, and to assess depressive symptom severity among doctors in HK.

To explore the factors associated with depression and suicidal ideation.

Hypotheses

The prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation in HK doctors will be higher than that in the general HK population and comparable to that of doctors overseas.

Depression and suicidal ideation will be related to such factors as age, gender, work setting, lifestyle behaviours and job satisfaction.

Methods

Medical school graduates from the University of Hong Kong between 1995 and 2014 who had a valid email or mailing address (N = 1607) were invited to participate in this cross-sectional study. Data collection occurred between January 29, 2016 to April 15, 2016. Subjects with valid email addressed were contacted by email to complete an online survey in English via SoGo Survey which also tracked the responses electronically. Three reminder emails were sent 14 days apart following the initial invitation. To increase sample size, paper questionnaires were subsequently mailed to graduates with available mailing addresses. Respondents were offered a coffee coupon as an incentive. The survey was voluntary, and response to the survey was taken as implied consent. The institutional review board allowed implied consent as the risk of harm from the survey study was minimal, the population was deemed not vulnerable, and the data collection was fully de-identified and anonymous. Collecting signatures for consent could increase a perceived risk for subject identification and deter potential respondents from completing the survey.

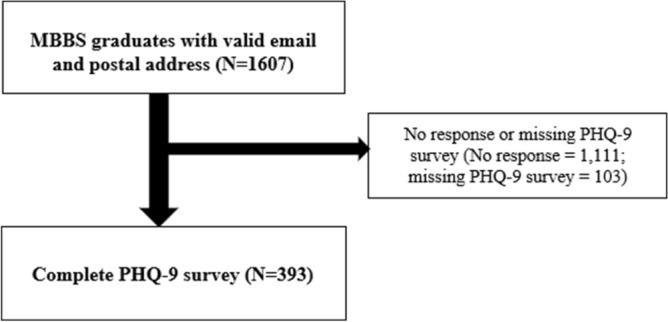

In total, 393 (384 by online and 112 by paper survey) respondents completed the PHQ-9 and other instruments shown below. The subject recruitment flow chart is shown in Fig. 1. Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/ Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (UW 15-405) approved the study and waived the need for signed informed consent. All research procedures were performed in accordance to the relevant regulations.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the sampling and response rates. MBBS, Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Study instruments

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to calculate the prevalence of depression and suicide intentions. The instrument consists of nine items based on the DSM-V definition for depression. Examples of the items are “having little interest or pleasure in doing things”, “feeling tired or having little energy” and “feeling down depressed and hopeless”. Each item is scored from zero (not at all) to three (nearly every day) with a minimum scores of zero (no depression) to 27 (severe depression)29. In this study, a PHQ > 9 was used as the cut-off indicating the presence of depression. Using a cut-off score of > 9, the PHQ-9 has a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 92% for the diagnosis of depression in HK30. PHQ-9 is a reliable and validated survey for depression and has a Cronbach of 0.8931. The presence of suicidal ideation was assessed using the final item of the PHQ-9, “in the past 2 weeks, how often have you been thinking that you would be better off dead or that you want to hurt yourself in some way?” Any positive response indicated the presence of suicidal ideation. A study comparing the endorsement of this single question to endorsement of suicidality in a structured clinical interview found the PHQ-9 suicide item had a specificity of 84% and sensitivity of 69% for identifying suicidality32.

The alcohol use disorders identification test version C (AUDIT-C) is a screening instrument using three questions to assess drinking behaviour including the frequency of drinking alcohol, the frequency of drinking more than 5 alcoholic units in one occasion, and the average number of alcoholic units consumed on typical day they drink33. In accordance to the HK guidelines, scores > 3 indicate a positive screen for at-risk drinking34. The scores in this survey were derived from the original questionnaire and adapted to the scoring system of AUDIT-C. Cronbach for AUDIT-C was previously reported in a range of 0.80–0.9135,36.

Items on job satisfaction and lifestyle behaviours were modified from existing doctor questionnaires37 and population health surveys from HK20. The original survey also included items on burnout and these findings have been published separately22.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle behaviour and career satisfaction of the respondents. Prevalence of depression was calculated by determining the proportion of respondents with PHQ-9 scores > 9. Those who reported several days, more than half the days and nearly every day were included for estimation of the prevalence of suicidal ideation and self-harm for the last question of the PHQ-9. Univariate linear regression was used to evaluate the effect of socio-demographic factors, lifestyle behaviours and career satisfaction on PHQ-9 total scores, PHQ-9 > 9, and PHQ-suicide. If the factors were significantly associated with the outcomes, these factors were considered in the multivariable linear regression models using a forward stepwise selection. Residual normality assumption was examined using Q./Q-plot. Multicollinearity was evaluated using a variance inflation factor. The variance inflation factor showed 1.23, which was below 10, indicating no multicollinearity between the potential factors.

Complete case analysis, using subjects without any missing data only, was conducted as a sensitivity analysis. Missing data for subjects’ characteristics were handled by multiple imputation using the chained equation method. Each missing value was imputed five times based on all characteristics of the participants including age, gender, marital status, having children, current specialty, setting of practice, satisfaction with present job position, satisfaction with being a medical doctor, average sleep per night, hours of work per week, regular exercise, at-risk drinker, current smoker, and PHQ-9 score. Five imputed datasets were generated, and the results were pooled according to the Rubin’s rule38.

All significance tests were two tailed and findings with P-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Version 15.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Socio-demographics, lifestyle behaviours and professional satisfaction characteristics

A total of 393 subjects were included for analysis. Data completion rates were over 95.7% for all items aside from drinking habits (89.8%) (see Supplementary Table 1). Missing data in marital status, satisfaction with present job position, average sleep per night, hours of work per week, at-risk drinker were imputed using multiple imputation. Subject characteristics including socio-demographics, lifestyle behaviours and professional satisfaction are shown in Table 1. Mean age of the respondents was 32.8 (SD = 5.4) years and 45% were female. Most respondents indicated they were satisfied with their current job position (78.6%) and with their career choice as a doctor (93.9%), 6.4% reported a previous mood disorder diagnosis, 75.8% performed regular exercise, and 25.8% were classified as at-risk drinkers. Only 2 participants identified as being a current smoker.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on sociodemographic, professional satisfaction and health status.

| Doctors (N = 393) | Doctors (N = 393) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | Professional satisfaction | ||

| Age | 32.8 ± 5.4 | Satisfied with present job position | 309 (78.6%) |

| Gender (female) | 177 (45.0%) | Satisfied with being a medical doctor | 369 (93.9%) |

| Marital status | Health status | ||

| Single, separated and divorced | 206 (52.3%) | Hours of work per week | 55.1 ± 15.3 |

| Married | 187 (47.7%) | Average sleep per night | 6.7 ± 1.0 |

| Having children | 135 (34.4%) | Regular exercise | 298 (75.8%) |

| Current specialty | At-risk drinker | 101 (25.8%) | |

| Anaesthesiology/emergency medicine/intensive care | 47 (12.0%) | Current smoker | 2 (0.5%) |

| Clinical oncology/dermatology and venerology/internal medicine | 73 (18.6%) | PHQ-9 > 9 | 63 (16.0%) |

| Pathology/radiology | 36 (9.2%) | PHQ-9 Suicide | 60 (15.3%) |

| Family medicine/general practice/community medicine | 72 (18.3%) | PHQ-9 Total Score | 5.3 ± 5.7 |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 26 (6.6%) | ||

| Orthopaedic surgery/otorhinolaryngology/surgery/ophthalmology | 84 (21.4%) | ||

| Paediatrics | 27 (6.9%) | ||

| Psychiatry | 28 (7.1%) | ||

| Setting of practice | |||

| Public | 332 (84.5%) | ||

| Private | 61 (15.5%) | ||

| Primary care | 67 (17.0%) |

Current smoker (Current smoker vs non-smoker/ex-smoker).

At-risk drinkers were defined if the doctors had 3 or more in AUDIT-C score.

Private Practice (Private Solo/ Private Hospital/Non-government organisation).

Public Practice (University/Government/Hospital Authority/Not applicable).

Regular exercise (5 or more days per week for at least 10 min per day / Any vigorous and moderate physical activities)

All data are represented in mean ± SD or total (%), as appropriate.

Prevalence of depression and suicidal and self-harm ideations

The prevalence of depression (PHQ-9 > 9) in the overall sample was 16.0% (males 15.8% and females 16.4%). The prevalence of suicide ideations and self-harm thoughts over the past 2 weeks was 15.3%.

Severity of depressive symptoms

The mean PHQ-9 score was 5.26 (SD = 5.65). 58.78% (n = 231) had PHQ-9 scores of 0–4 (minimal depressive symptoms), 25.19% (n = 99) had scores of 5–9 (mild depressive symptoms), 7.12% (n = 28) had scores of 10–14 (moderately depressive symptoms), 6.11% (n = 24) had scores of 15–19 (moderately severe depressive symptoms) and 2.8% (n = 11) had scores 20–27 (severe depressive symptoms).

Factors associated with depression, suicidal and self-harm ideations

Tables 2, 3, 4 and Fig. 2 shows the results of the regression analyses identifying the factors associated with PHQ-9 total scores, PHQ-9 > 9 and PHQ-9 suicide and self-harm risk using univariate then forward stepwise selection to identify significant associations. Only sleeping fewer hours per night (Coeff = − 1.441, 95% CI − 2.012 to − 0.870) was associated with higher PHQ-9 scores (Table 2). Using a PHQ-9 cut-off > 9 as a positive screen for depression, only average hours of sleep had a significant odds ratio (OR = 0.499, 95% CI 0.363–0.688) indicating that sleeping 1 h less was associated with a 50% increased odds of having depression (Table 3). PHQ-9 scores and risk of screening positive for depression were not significantly associated with any socio-demographic factors, professional satisfaction, and other lifestyle behaviours such as hours of work, smoking status, regular exercise, and at-risk drinking. Being married reduced the odds of having suicidal ideations and self-harm thoughts by 52.5% (OR = 0.475, 95% CI 0.266–0.849, P = 0.012) and sleeping 1 h less increased that odd by 31% (OR = 0.694, 0.509–0.948, P = 0.022) (Table 4). Apart from marital status and hours of sleep, no other socio-demographic factors, professional satisfaction or other lifestyle behaviours were significantly associated with suicidal ideations and self-harm thoughts. A sensitivity analysis using the complete case analysis demonstrated similar results compared to the main analysis (Supplementary Tables 2–4).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic, professional satisfaction and lifestyle behaviour associated with PHQ-9 total score by regression analysis.

| Factor† | PHQ-9 score (N = 393) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Forward stepwise selection | |||||

| Coeff | 95% CI | P-value | Coeff | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||

| Age | − 0.071 | (− 0.176, 0.033) | 0.181 | |||

| Female (vs male) | 0.685 | (− 0.442, 1.812) | 0.233 | |||

| Married (vs single, separated and divorced) | − 1.129* | (− 2.249, − 0.009) | 0.048* | NA | ||

| Having children (vs no children) | − 0.952 | (− 2.131, 0.227) | 0.113 | |||

| Private setting of your practice (vs public) | − 1.048 | (− 2.595, 0.500) | 0.184 | |||

| Current specialty | ||||||

| Anaesthesiology/emergency medicine/intensive care | 1.891 | (− 0.201, 3.984) | 0.076 | |||

| Clinical oncology/dermatology and venerology/internal medicine | 0.746 | (− 1.108, 2.599) | 0.429 | NA | ||

| Pathology/radiology | − 0.028 | (− 2.306, 2.250) | 0.981 | |||

| Family medicine/general practice/community medicine | Reference group | |||||

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 1.214 | (− 1.339, 3.767) | 0.351 | |||

| Orthopaedic surgery/otorhinolaryngology/surgery/ophthalmology | 0.706 | (− 1.086, 2.498) | 0.439 | |||

| Paediatrics | 1.296 | (− 1.222, 3.814) | 0.312 | |||

| Psychiatry | 0.337 | (− 2.148, 2.823) | 0.790 | |||

| Professional satisfaction | ||||||

| Satisfied your present job position (vs not satisfied) | − 0.424 | (− 1.793, 0.946) | 0.543 | |||

| Satisfied with being a medical doctor (vs not satisfied) | − 0.875 | (− 3.219, 1.469) | 0.464 | NA | ||

| Lifestyle behaviours | ||||||

| Average sleep per night | − 1.441* | (− 2.012, − 0.870) | < 0.001* | − 1.441* | (− 2.012, − 0.870) | < 0.001* |

| Hours of work per week | 0.048* | (0.011, 0.085) | 0.010* | |||

| Current smoker (vs non-smoker/ex-smoker) | 5.767 | (− 2.106, 13.640) | 0.151 | |||

| Regular exercise (vs no regular exercise) | − 1.612* | (− 2.914, -0.310) | 0.015* | NA | ||

| At-risk drinker | 0.727 | (− 0.646, 2.101) | 0.297 | |||

CI = Confidence Interval; Coeff = Coefficient; NA = Not Applicable.

Current Smoker (Current smoker vs Non-smoker/ex-smoker).

Regular exercise (5 or more days per week for at least 10 min per day / Any vigorous and moderate physical activities).

Private Practice (Private Solo/ Private Hospital/Non-government organisation).

Public Practice (University/Government/Hospital Authority/Not applicable).

At-risk drinkers were defined if the doctors had 3 or more in AUDIT-C score.

* Significant with p-value < 0.05.

† Variable in brackets is the reference category for independent variables.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic, professional satisfaction and lifestyle behaviour associated with PHQ-9 > 9 by regression analysis.

| Factor† | PHQ-9 > 9 (N = 393) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Forward stepwise selection | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||

| Age | 0.961 | (0.912, 1.012) | 0.133 | |||

| Female (vs male) | 1.049 | (0.611, 1.801) | 0.863 | |||

| Married (vs single, separated and divorced) | 0.503* | (0.289, 0.874) | 0.015* | NA | ||

| Having children (vs no children) | 0.664 | (0.364, 1.210) | 0.181 | |||

| Private setting of your practice (vs public) | 0.325* | (0.113, 0.930) | 0.036* | |||

| Current specialty | ||||||

| Anaesthesiology/emergency medicine/intensive care | 2.743* | (1.024, 7.344) | 0.045* | |||

| Clinical oncology/dermatology and venerology/internal medicine | 1.419 | (0.535, 3.764) | 0.482 | NA | ||

| Pathology/radiology | 1.600 | (0.510, 5.022) | 0.421 | |||

| Family medicine/general practice/ community medicine | Reference group | |||||

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 1.455 | (0.399, 5.307) | 0.570 | |||

| Orthopaedic surgery/otorhinolaryngology/surgery/ophthalmology | 1.205 | (0.457, 3.182) | 0.706 | |||

| Paediatrics | 2.800 | (0.903, 8.684) | 0.075 | |||

| Psychiatry | 1.333 | (0.368, 4.837) | 0.662 | |||

| Professional satisfaction | ||||||

| Satisfied your present job position (vs not satisfied) | 0.942 | (0.492, 1.805) | 0.858 | |||

| Satisfied with being a medical doctor (Vs not satisfied) | 0.952 | (0.314, 2.885) | 0.930 | NA | ||

| Lifestyle behaviours | ||||||

| Average sleep per night | 0.499* | (0.363, 0.688) | < 0.001* | 0.499* | (0.363, 0.688) | < 0.001* |

| Hours of work per week | 1.018* | (1.000, 1.036) | 0.044* | |||

| Current Smoker (vs non-smoker/ex-smoker) | 5.306 | (0.328, 85.969) | 0.240 | |||

| Regular exercise (vs no regular exercise) | 0.632 | (0.351, 1.140) | 0.128 | NA | ||

| At-risk drinker | 1.503 | (0.779, 2.902) | 0.222 | |||

CI = Confidence Interval; OR = Odds Ratio; NA = Not Applicable.

Current Smoker (Current smoker vs Non-smoker/ex-smoker).

Regular exercise (5 or more days per week for at least 10 min per day / Any vigorous and moderate physical activities).

Private Practice (Private Solo/ Private Hospital/Non-government organisation).

Public Practice (University/Government/Hospital Authority/Not applicable).

At-risk drinkers were defined if the doctors had 3 or more in AUDIT-C score.

* Significant with p-value < 0.05.

† Variable in brackets is the reference category for independent variables.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic, professional satisfaction and lifestyle behaviour associated with PHQ-9 suicide score by regression analysis.

| Factor† | PHQ-9 suicide (N = 393) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Forward stepwise selection | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||

| Age | 0.967 | (0.918, 1.020) | 0.218 | |||

| Female (vs male) | 0.922 | (0.529, 1.604) | 0.773 | NA | ||

| Married (vs single, separated and divorced) | 0.433* | (0.244, 0.768) | 0.004* | 0.475* | (0.266, 0.849) | 0.012* |

| Having children (vs no children) | 0.533 | (0.282, 1.010) | 0.054 | NA | ||

| Private setting of your practice (vs Public) | 0.562 | (0.230, 1.370) | 0.205 | |||

| Current specialty | ||||||

| Anaesthesiology/emergency medicine/intensive care | 2.139 | (0.810, 5.651) | 0.125 | |||

| Clinical oncology/dermatology and venerology/internal medicine | 1.242 | (0.481, 3.205) | 0.654 | NA | ||

| Pathology/radiology | 0.636 | (0.161, 2.511) | 0.519 | |||

| Family medicine/general practice/community medicine | Reference group | |||||

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 1.667 | (0.502, 5.531) | 0.404 | |||

| Orthopaedic surgery/otorhinolaryngology/surgery/ophthalmology | 1.400 | (0.567, 3.457) | 0.466 | |||

| Paediatrics | 1.217 | (0.342, 4.339) | 0.762 | |||

| Psychiatry | 0.840 | (0.210, 3.360) | 0.805 | |||

| Professional satisfaction | ||||||

| Satisfied your present job position (vs not satisfied) | 0.784 | (0.413, 1.489) | 0.457 | |||

| Satisfied with being a medical doctor (vs not satisfied) | 0.666 | (0.239, 1.857) | 0.437 | NA | ||

| Lifestyle behaviours | ||||||

| Average sleep per night | 0.659* | (0.486, 0.894) | 0.007* | 0.694* | (0.509, 0.948) | 0.022* |

| Hours of work per week | 1.011 | (0.994, 1.029) | 0.210 | |||

| Current smoker (vs non-smoker/ex-smoker) | 5.627 | (0.347, 91.214) | 0.224 | |||

| Regular exercise (vs no regular exercise) | 1.328 | (0.673, 2.620) | 0.413 | NA | ||

| At-risk drinker | 1.238 | (0.659, 2.327) | 0.507 | |||

CI = Confidence Interval; OR = Odds Ratio; NA = Not Applicable.

Current Smoker (Current smoker vs Non-smoker/ex-smoker).

Regular exercise (5 or more days per week for at least 10 min per day/Any vigorous and moderate physical activities).

Private Practice (Private Solo/ Private Hospital/Non-government organisation).

Public Practice (University/Government/Hospital Authority/Not applicable).

At-risk drinkers were defined if the doctors had 3 or more in AUDIT-C score.

* Significant with P-value < 0.05.

† Variable in brackets is the reference category for independent variables.

Figure 2.

Sociodemographic, professional satisfaction and lifestyle behaviours associated with PHQ-9 score by regression with forward stepwise selection. PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, CI = Confidence Interval; Coeff = Coefficient; OR = Odds Ratio, * Significant with p-value < 0.05.

Discussion

This study found that a significant proportion of HK physicians are depressed (16%) and have thoughts of suicide or self-harm (15.3%). These rates appear to be lower than global estimates for physician depression and suicide ideation8,18,25,39, but higher than in the HK general population19,20. This is consistent with research that shows that physicians are at a higher risk for depression and suicide7. Our initial hypothesis that the prevalence of HK physician would be higher than that of the primary care population of 10.7%19, appears to be correct; however, the prevalence of suicidal ideations in this physician sample were much higher than the HK population estimate of 3.5%20. Our findings were also higher than those by Siu et al. which found 4.9% of HK doctors had suicidal ideations21. This could be a result of the wording of the PHQ-9 suicidality item as the question assesses both self-harm and suicidal ideation together which may result in more positive responses as suicidal ideation and self-harm are not differentiated. However, a systematic review of 61 studies revealed that globally, 17% of physicians have suicidal ideations, which is just slightly higher than our study findings25. Moreover, the severity of depression in our sample showed that a majority of those who screened positive for depression had either mild and moderate depression, and there was a small subset (2.8%) that had severe depression consistent with previous depressive study of HK interns23. Such high screening levels for potential suicidality and depressive symptoms in HK physicians warrants further exploration.

Association of lifestyle behaviours with depression and suicidal ideation

In this study population, the only factor significantly associated with higher depression symptom scores and odds of being screened positive for depression was sleeping less hours per night. The relationship between sleep deprivation and depression in physicians has been studied extensively but the evidence on the cause and effect is conflicting and confusing. One possible mechanism for sleep deprivation leading to depressive disorders is explained by a model that describes that fatigue can lead to depression40 and there is evidence to suggest that sleep deprivation leads to fatigue41. Another mechanism described is that poor sleep impairs emotional regulation, such that people are unable to monitor and evaluate emotions and to adjust to the situation, and this has been shown to lead to depression42. However, conflicting evidence exists. Sleep deficit is often a symptom of depression which may imply depression is the cause rather than the effect of sleep deficits; and depression and sleep deficits share similar risk factors and biological factors7,43–45.

This study also showed that having less sleep increased the odds of suicidal ideations and self-harm behaviour such that sleeping 1 h less increased the odds of suicidal thoughts by 31%. Sleep deficits is a recognized risk factor for suicidal ideations, but this could be confounded by co-existing depression which is seen as a risk factor and symptom for suicidal thoughts46,47. In addition, research supports that sleep loss may lead to impulsivity, thus raising unplanned suicidal behaviour46. Others have tried to explain the relationship between sleep and suicidal ideation at a biological level, with serotonin levels appearing to play a role in both constructs48. Moreover, the average sleep physicians had per night in this study was 6.7 h, which is in the lower end of the average hours of sleep that adults need (6–9 h)49. This may indicate a subset of physicians who are not getting adequate sleep. Sleep deprivation in physicians is related to poor outcomes including increased fatigue and medical errors50,51, and worryingly sleep deprived doctors are unable to recognize self-fatigue50. The relationship between sleep, suicide, depression and how each can independently affect patient care means that getting adequate sleep in physicians is important to address50.

At-risk drinking, smoking, exercise, and work hours were not associated with depression and suicide in this study. Literature reports alcoholism is strongly associated with suicide and depression, which is inconsistent with the results of this study11,12. This is possibly because the survey items in the present study were not able to differentiate “at-risk” drinkers to those who may meet the definition for alcohol dependence or problem drinkers. The latter are more likely to use alcohol as a coping mechanism of depression or drink excess alcohol causing significant interference with the daily life to cause depression12. Likewise, there is evidence that non-smokers have less depressive symptoms17, but this was not seen in this study likely because there were only 2 (out of 393) respondents who identified being a current smoker and thus making it difficult to conclude any relationship. Our study also showed most doctors performed some regular exercise. Exercise has been seen as a protective factor against depression and suicide risks17,52,53, but this was not seen in the present study. This could be because different studies use different criteria to quantify exercise and thereby exerting different effects. Interestingly, it has been shown that exercise as an intervention can lead to fewer depressive symptoms and better sleep patterns, which can thereby reduce suicide risk53.

The evidence on the relationship between work hours and depression remains divided. Whilst longer work hours has been associated with depression in physicians in some studies17,54, this current and other studies have not supported this relationship7,44. Our study did not find that longer work hours were associated with greater suicide ideation as in other studies55,56. Work hours is only one part of the work demands for physicians whereas other studies have also examined working on shifts, evening calls, dealing with patients, relatives and colleagues, and making mistakes as potential factors which may augment the understanding of the effect of work demands on depression17,22,57. Furthermore, research suggest that suicidal thoughts may be less likely due to work demands and more likely due to personal and family problems, which we will discuss in the next section58.

Sociodemographic factors associations with depression and suicidal ideations

Of the sociodemographic factors, only marriage was found to be a protective factor in this study against suicide ideations and self-harm. Research has shown that marriage is protective for depression: Both men and women have less distress and depression when married19 and being single is a well-documented risk factor for suicide, especially in women59–61. Marriage often reflects an effective family support system, which can have protective effects against self-harm behaviours and depression58,60. However, the results of this study are confusing with marriage only being associated with suicidal ideations and self-harm but not with depression. Results from other studies do not support the relationship between marriage and depression18,44 suggesting that marital status alone may not be enough to explain the relationship and perhaps other factors such as marital satisfaction, marital problems or family satisfaction may play a role62,63. In the Chinese culture, positive family relationships are considered an important factor for mental well-being. Family harmony is a measure of how well the family functions together including how well they accommodate each other and have successful daily interactions63. Research has shown that for families in HK who reported low family harmony had stronger associations for depressive symptoms63. Future research may want to explore how family harmony plays a role in physician depression and suicide ideations and self-harm behaviours.

Age was not found to be significantly associated with depression or suicidality in this study. This is consistent with a systematic review of 46 studies which found that age is not associated with depression7. Some studies suggest that older age increases suicide risk which may be related to a loss of connection with colleagues following retirement leading to increased distress64,65. However, our sample did not include older physicians and the lack of significance could have been because of the relatively narrow age range of our sample, who were all within 20 years of graduation.

There is a large body of evidence indicating women are at greater risk for depression both globally and in HK19,66. Studies have also shown that female physicians are at greater risk for depression and suicide25,54. In our sample, gender was not a significant factor, similar to observations in other physician studies7,44. In HK, higher-income families and in particular in families where the wife has a high-income job, hiring a live-in domestic helper to assist to what traditional Chinese people see as “women’s tasks” is common67. These at-home responsibilities are often perceived as a possible reason for increased risk of depression and suicide in women physician25. With easier accessibility and affordability of full-time domestic help in HK, many of the ‘at-home’ responsibilities that are typically are borne by women are reduced and may potentially reduce the risk of depression and suicide in female physicians. Conversely, there may be other factors causing the relatively higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation in men, and the reasons for their elevated risks need further investigation.

Choice of specialty was not a significant factor associated with depression and suicidality in our sample. Whilst some studies have found that specialty may have an effect, the evidence remains inconclusive that any one particular specialty may be associated with a greater risk of depression and suicide intention10,25,44. In our study, sample sizes were not large enough to perform subgroup analyses by individual specialties.

Professional satisfaction association with depression and suicidal ideations

Our study did not reveal any significant associations between job satisfaction and depression, despite 485 studies in a meta-analysis indicating that there is a strong relationship between low job satisfaction, burnout, and increased risk of depression15. The respondents in this study expressed high levels of job satisfaction as measured by these two items: “how satisfied are you with your current job position (78.6% satisfied or very satisfied) and “how satisfied are you with being a medical doctor” (93.9% satisfied or very satisfied). Our previous study examining burnout within the same cohort also did not observe any association between career satisfaction and burnout; although an earlier HK physician study did21,22. In that earlier study, only 51.4% expressed satisfaction with their job, which may reflect a difference in our sample cohort as only public sector doctors were included in their sample and this current study included doctors working in both private and public sector settings.

Help-seeking behaviour

Less than half of those who screened positive for depression reported having a diagnosis of a mood disorder indicating a large proportion of HK doctors with depression may be unaware of their mental health problem or are not seeking appropriate care from a mental health professional despite recognizing their mental illness. This is consistent with a previous HK study showing that doctors tend to treat themselves rather than seek help68. According to research, physicians face psychological barriers to seeking care for their mental health issues, including feelings of shame and embarrassments, the notion that doctors should appear healthy, and the belief that mental illness is a weakness69. Studies also have suggested that it is hard for doctors to adopt the “role reversal” and become a patient69. This problem is not unique to HK, and it is a global issue that needs to be addressed70,71.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, with a response rate of just 24.5%, the findings may be susceptible to response bias: physicians who are more depressed may either be more likely to respond because the topic is relevant or less likely to respond because they are more indifferent. Second, despite having two medical schools and foreign-trained doctors in HK, this study only sampled graduates from one medical school and therefore the findings might not be generalizable to the entire HK doctor population. We studied from a single medical school because pragmatically, we had the contact information of these graduates, which accounted for roughly half of all local graduates72. Third, not all age groups were represented in this study as the sample were all within 20 years of graduation, and the age of the participants ranged only between 24 and 45 years old. However, because sampling was adequate from the range of ages across the study sample, it still allowed for relevant relationships to be made. Moreover, in HK, doctors in the private sector comprise of about 48.9% of all doctors, but we only sampled 15.5% of private doctors73. This can be explained by the likelihood that more recent graduates are undergoing training which is carried out in the public sector in HK. Lastly, we are unable to establish whether the associations are causally associated because the survey was cross-sectional.

Conclusion

Doctors in HK are at relatively high risk of having depression and suicidal thoughts; however, many doctors do not seek mental health care or get diagnosed. With such high levels of mental morbidity, better systems are needed to support doctors to better self-care and reduce barriers to seeking help. From our findings, encouraging better self-care in particular better sleep and exercise may be helpful for HK doctors. Lack of sleep can impact patient care directly and indirectly through its effect on increased risk of depression and suicidal risk. Healthcare institutions could enable better physician self-care by optimizing work schedules and promoting wellness education. Implementing well-being curricula into medical school to encourage students develop better self-awareness and self-care might help enhance resilience or reduce the stigma of mental health help-seeking later in their careers.

Strategies to reduce the barriers to accessing mental health care could be trialed such as introducing peer support or counselling schemes and encouraging all physicians to have their own family doctor. Some countries have addressed barriers to help-seeking by introducing doctor-specific health initiatives with staff and resources dedicated to identifying and helping doctors with health problems. Doctors could be screened for depression throughout their career to identify those who may require mental health support. Physician organizations could do more to educate physicians who care for other doctors about maintaining the right balance between respecting their patient's position as a medical professional and listening to their views about their treatment plan, while also standing firm on what is best for the patient’s health.

Fortunately, despite high mental morbidity, work satisfaction levels remain relatively high amongst HK doctors and could potentially act as a protective factor preventing doctors from leaving the profession or opting for early retirement.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants the Bau Institute of Medical and Health Sciences Education, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of HK and the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine for their support in this study. We would also like to thank Karina Chan who helped with the project management and data collection.

Abbreviations

- AUDIT – C

Alcohol use disorders identification test version C

- HK

Hong Kong

- PHQ-9

Patient health questionnaire-9

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

C.S.L., J.C., and W.Y.C. conceptualised and designed the study. W.Y.C., J.C., and C.S.L. acquired the data. E.Y.F.W., A.P.P.N., and W.Y.C. analysed and interpreted the data. A.P.P.N. performed the literature review and A.P.P.N., E.Y.F.W. and W.Y.C. drafted the manuscript. E.Y.F.W. prepared all the figures and tables. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Funding

This work was financially supported by The University of Hong Kong’s Small Project Fund Grant Number 104003643.058678.22500.301.01. It was also supported by the Bau Institute of Medical and Health Sciences Education, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong who provided research assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-98668-4.

References

- 1.Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet388(10053), 1545–1602 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Ösby U, et al. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):844–850. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bostwick JM, Pankratz VS. Affective disorders and suicide risk: A reexamination. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):1925–1932. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization, W.H., Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. 2015.

- 5.Broadhead WE, et al. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2524–2528. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450190056028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lerner D, Henke RM. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008;50(4):401–410. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31816bae50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joules, N., Williams, D.M., & Thompson, A.W. Depression in resident physicians: A systematic review.Open J. Depress.2014 (2014).

- 8.Mata DA, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2015;314(22):2373–2383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenes GA. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in primary care patients. Primary Care Compan. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;9(6):437–443. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v09n0606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu K, Marshall V. Prevalence of depression and distress in a large sample of. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(12):1561–1566. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.12.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: An empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:S11–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR. The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000;20(2):173–189. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fluharty M, et al. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017;19(1):3–13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu C, et al. Social support and depressive symptoms among physicians in tertiary hospitals in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03219-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: A meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005;62(2):105. doi: 10.1136/oem.2002.006734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin X, Wang S, Hsieh C-R. The prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among adults in China: Estimation based on a National Household Survey. China Econ. Rev. 2018;51:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong Y, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and related risk factors among physicians in China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e103242–e103242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J-N, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among Chinese doctors: A cross-sectional survey. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 2010;83(8):905–911. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin WY, et al. Detection and management of depression in adult primary care patients in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional survey conducted by a primary care practice-based research network. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014;15(1):30–30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health, H.a.D.o.C.M., HKU : Report on Population Health Survey 2003/2004.

- 21.Siu CF, Yuen S, Cheung A. Burnout among public doctors in Hong Kong: Cross-sectional survey. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012;18(3):186–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng APP, et al. Prevalence and severity of burnout in Hong Kong doctors up to 20 years post-graduation: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e040178. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam TP, et al. Psychological well-being of interns in Hong Kong: What causes them stress and what helps them. MED TEACH. 2010;32(3):e120–e126. doi: 10.3109/01421590903449894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keilp JG, et al. Suicidal ideation and the subjective aspects of depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;140(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dutheil F, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, Y., Liu, L., & Xu, H., Alarm bells ring: Suicide among Chinese physicians: A STROBE compliant study.Medicine, 96(32) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Heponiemi T, et al. Health, psychosocial factors and retirement intentions among Finnish physicians. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 2008;58(6):406–412. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqn064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health, H. 2018 Health Manpower Survey on Doctors. 2018 [cited 2021 August 8 2021]; https://www.dh.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_hms/keyfinding_dr18.html.

- 29.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002;32(9):509–515. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng CM, Cheng M. To validate the Chinese version of the 2Q and PHQ-9 questionnaires in Hong Kong Chinese patients. Hong Kong Pract. 2007;29(10):381–390. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uebelacker, L.A., et al., Patient health questionnaire depression scale as a suicide screening instrument in depressed primary care patients: A cross-sectional study.Prim. Care Comp. CNS Disord.13(1), . PCC.10m01027 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Bush K, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health, C.f.H.P.a.D.o. Alcohol and Health Questionnaire (AUDIT). 2017 2017 [cited 2019; https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_audit_2017_audit_questionnaire_en.pdf.

- 35.Osaki Y, et al. Reliability and validity of the alcohol use disorders identification test—Consumption in screening for adults with alcohol use disorders and risky drinking in Japan. Asian Pac. J. Cancer. 2014;15(16):6571–6574. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.16.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rumpf H-J, et al. Screening questionnaires for problem drinking in adolescents: Performance of AUDIT, AUDIT-C, CRAFFT and POSIT. Eur. Addict. Res. 2013;19(3):121–127. doi: 10.1159/000342331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor K, Lambert T, Goldacre M. Future career plans of a cohort of senior doctors working in the National Health Service. J. R. Soc. Med. 2008;101(4):182–190. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2007.070276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin, D.B., Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Vol. 81. Wiley (2004).

- 39.Firth-Cozens J. Individual and organizational predictors of depression in general practitioners. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1998;48(435):1647–1651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker G. Classifying depression: should paradigms lost be regained? Am. J. Psychiat. 2000;157(8):1195–1203. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavidor M, Weller A, Babkoff H. How sleep is related to fatigue. Br. J. Health. Psychol. 2003;8(1):95–105. doi: 10.1348/135910703762879237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Leary K, Bylsma LM, Rottenberg J. Why might poor sleep quality lead to depression? A role for emotion regulation. Cogn. Emot. 2017;31(8):1698–1706. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1247035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen IM, et al. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad. Med. 2006;81(1):82–85. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200601000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fahrenkopf AM, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):488–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sokratous S, et al. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of depressive symptoms among Cypriot university students: A cross-sectional descriptive co-relational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):235–235. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0235-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Porras-Segovia A, et al. Contribution of sleep deprivation to suicidal behaviour: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019;44:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernert RA, et al. Sleep disturbances as an evidence-based suicide risk factor. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernert RA, Joiner TE. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: A review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2007;3(6):735–743. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hor H, Tafti M. How much sleep do we need? Science. 2009;325(5942):825–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1178713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Howard, S.K. Sleep Deprivation and Physician Performance: Why Should I Care? In Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. Taylor & Francis (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Kalmbach, D.A., et al., Sleep Disturbance and Short Sleep as Risk Factors for Depression and Perceived Medical Errors in First-Year Residents.Sleep. 40(3) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Cooney G, Dwan K, Mead G. Exercise for depression. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2014;311(23):2432–2433. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson CL, et al. The impact of exercise on suicide risk: Examining pathways through depression, PTSD, and sleep in an inpatient sample of veterans. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2013;43(3):279–289. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sen S, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):557–565. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoon J-H, et al. Relationship between long working hours and suicidal thoughts: Nationwide data from the 4th and 5th Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129142–e0129142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park S, et al. The negative impact of long working hours on mental health in young Korean workers. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0236931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Firth-Cozens J. Emotional distress in junior house officers. Br. Med. J. 1987;295:533–536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6597.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Downey GB, McDonald J, Downey RG. Welfare of Anaesthesia trainees survey. Anaesth. Intensive Care. 2017;45(1):73–78. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1704500111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Høyer G, Lund E. Suicide among women related to number of children in marriage. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):134–137. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140060006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hem E, et al. The prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among Norwegian physicians. Results from a cross-sectional survey of a nationwide sample. Eur. Psychiatry. 2000;15(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tyssen R, et al. Suicidal ideation among medical students and young physicians: A nationwide and prospective study of prevalence and predictors. J. Affect. Disord. 2001;64(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fincham FD, et al. Marital satisfaction and depression: Different causal relationships for men and women? Psychol. Sci. 1997;8(5):351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00424.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kavikondala S, et al. Structure and validity of family harmony scale: An Instrument for Measuring Harmony. Psychol. Assess. 2016;28(3):307–318. doi: 10.1037/pas0000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ji YD, et al. Assessment of risk factors for suicide among US health care professionals. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):713–721. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Danhauer SC, Files K, Freischlag JA. Physician suicide—Reflections on relevance and resilience. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):721–722. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Albert PR. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. JPN. 2015;40(4):219–221. doi: 10.1503/jpn.150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheung AK-L, Lui L. Hiring domestic help in Hong Kong: The role of gender attitude and Wives’ income. J. Fam. Issues. 2017;38(1):73–99. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14565700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen JY, et al. Doctors' personal health care choices: A cross-sectional survey in a mixed public/private setting. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brooks SK, Gerada C, Chalder T. Review of literature on the mental health of doctors: Are specialist services needed? J. Ment. Health. 2011;20(2):146–156. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2010.541300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swapnil S, Mehta BA, Matthew L, Edwards MD. Suffering in Silence: Mental Health Stigma and Physicians' Licensing Fears. Am. J. Psychiatry Resident. J. 2018;13(11):2–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2018.131101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muhamad Ramzi, N.S.A. et al. Help-seeking for depression among Australian doctors.Intern. Med. J. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Food and Health Bureau, T.G.o.H.K.S.A.R. Report of the Strategic Review on Healthcare Manpower Planning and Professional Development; Chapter 1 - Hong Kong Healthcare System and Healthcare Professionals. https://www.fhb.gov.hk/download/press_and_publications/otherinfo/180500_sr/e_ch1.pdf.

- 73.Health, D.o., 2015 Health Manpower Survey on Doctors. 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.