Abstract

Background: Suicidality is common in major depressive disorder (MDD), but there has been no systematic review published about all aspects of suicidality. This meta-analysis and systematic review compared the prevalence of the whole range of suicidality comprising suicidal ideation (SI), suicide plan (SP), suicide attempt (SA), and completed suicide (CS), between patients with MDD and non-MDD controls.

Methods: Major international (PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, EMBASE) and Chinese (Chinese Nation Knowledge Infrastructure and WANFANG) databases were systematically and independently searched from their inception until January 12, 2021.

Results: Fifteen studies covering 85,768 patients (12,668 in the MDD group and 73,100 in the non-MDD group) were included in the analyses. Compared to non-MDD controls, the odds ratios (ORs) for lifetime, past month, past year, and 2-week prevalence of SI in MDD were 2.88 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.30–27.22, p = 0.36], 49.88 (95% CI = 2–8.63, p < 0.001), 13.97 (95% CI = 12.67–15.41, p < 0.001), and 24.81 (95% CI = 15.70–39.22, p < 0.001), respectively. Compared to non-MDD controls, the OR for lifetime SP in MDD was 9.51 (95% CI = 7.62–11.88, p < 0.001). Compared to non-MDD controls, the ORs of lifetime and past-year prevalence of SA were 3.45 (95% CI = 1.58–7.52, p = 0.002), and 7.34 (95% CI = 2.14–25.16, p = 0.002), respectively, in MDD patients. No difference in the prevalence of CS between MDD and controls was found (OR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.23–2.02, p = 0.50).

Conclusions: MDD patients are at a higher risk of suicidality, compared to non-MDD controls. Routine screening for a range of suicidality should be included in the management of MDD, followed by timely treatment for suicidal patients.

Systematic Review Registration: Identifier [INPLASY202120078].

Keywords: major depressive disorder, meta-analysis, suicide attempt, comparative study, suicidality

Introduction

Suicidality is a major global health problem. It is estimated that there are approximately 800,000 people per year who die by suicide, and every 40 seconds, one person completes suicide; in addition, suicide confers huge personal and familial suffering and further compounds healthcare burden (1). For instance, suicide and related problems accounted for 1.4% of the global burden of diseases in 2020 (1).

Suicidality comprises suicidal ideation (SI), suicide plan (SP), suicide attempt (SA), and completed suicide (CS). SI refers to thoughts or wishes about ending one's life, SP refers to making plans for suicide, and SA refers to acts to end one's life (2). Persons with SI, SP, and SA are more likely to have future suicide than those without (3). Therefore, to reduce the risk of future suicide, it is important to understand the patterns of SI, SP, and SA.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common psychiatric disorder, which accounts for up to 87% of CSs (4). Apart from CS, other aspects of suicidality are also common in MDD. For instance, in a recent meta-analysis, the prevalence rates of SI and SA in MDD were 53.1 and 31%, respectively (5, 6).

Studies that compared suicidality between MDD and non-MDD controls yielded conflicting findings. The National Comorbidity Survey in the United States found that the risk of SA in MDD was five-fold higher than in the general population (7). Patients with a major depressive episode have increasing risk of CS after SA (8). A meta-analysis of 20 studies concluded that patients with psychotic depression had a two-fold higher risk of SA compared to their non-psychotic counterparts (9). A thorough search of the literature could not find any meta-analysis comparing the comprehensive range of suicidality (i.e., SI, SP, SA, and CS) between MDD and non-MDD groups. The aim of this meta-analysis was to compare the risk of the whole range of suicidality between those with and without MDD.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

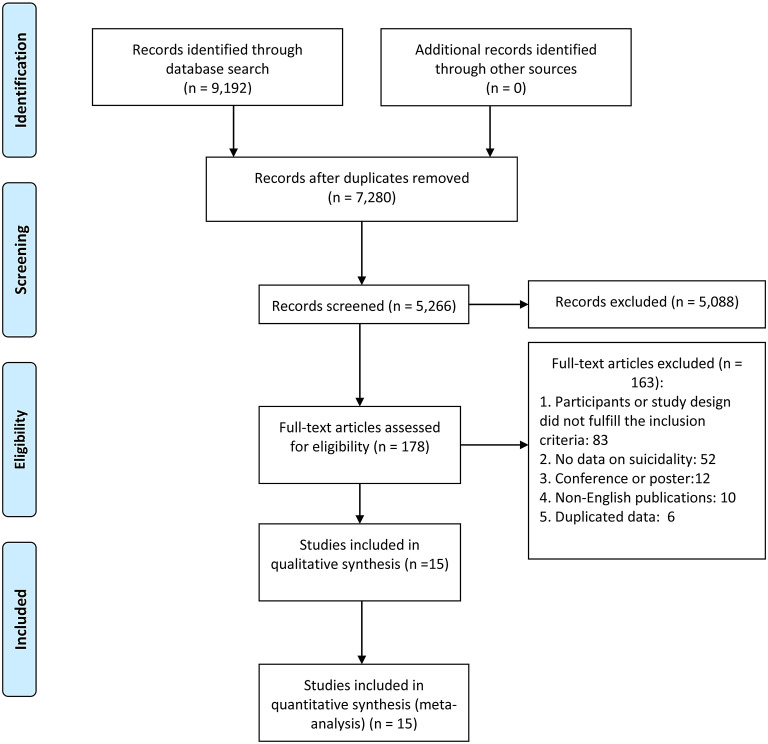

This meta-analysis was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses) (10). The protocol was registered with INPLASY (International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols) (registration number: INPLASY202120078). Two investigators (H.C. and X.M.X.) independently searched the literature in PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, EMBASE, Chinese Nation knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and WANFANG databases from their commencement dates until January 12, 2021, using the following search terms: [(suicid* ideation) OR (suicid* idea) OR (suicide thought) OR (suicide plan) OR (self-injurious behavior) OR (self-harm) OR (self-injury) OR (suicid*) OR (self-mutilation) OR (self-immolation) OR (self-inflicted) OR (self-slaughter) OR (self-destruction)] AND [(major depress*) OR (unipolar depress*) OR (Depressive Disorder, Major)] AND [(epidemiology) OR (prevalence) OR (rate)]. The same two investigators independently screened the titles and abstracts and then read the full texts of potentially relevant papers for eligibility. The reference lists of relevant review papers were checked manually to identify missing studies. Uncertainty in the literature search was resolved by a discussion with a senior investigator (X.Y.T.). The process of the literature search is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria according to the PICOS acronym were as follows: participants (P): patients with MDD diagnosed according to international or local diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (11) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (12); intervention (I): not applicable; comparison (C): persons without MDD or other major psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; outcomes (O): the prevalence of a range of suicidality or data that could generate prevalence of suicidality; and study design (S): case–control or cohort studies (only the baseline data of cohort studies were extracted). Studies involving MDD patients combined with other disorders or other special populations (e.g., children or adolescents, pregnant women, soldiers) were also excluded. If more than one paper was published based on the same dataset, only the one with the largest sample size was included in the analyses.

Data Extraction and Study Quality Assessment

The same two investigators independently conducted the data extraction by using a standard form. Study and patient characteristics, such as the first author, year of publication, survey time, study location and design, source of patients (e.g., inpatients, outpatients, community, or mixed), total sample size, diagnostic criteria of MDD and MDD sample size, non-MDD group diagnoses and sample size, proportion of males, type of suicidality, mean age, and timeframe of suicidality, were extracted. Study quality was assessed using a standardized instrument for epidemiological studies (13, 14) with the following eight items: (1) target population was defined clearly; (2) probability sampling or entire population surveyed; (3) response rate was ≥80%; (4) non-responders were clearly described; (5) sample was representative of the target population; (6) data collection methods were standardized; (7) validated criteria were used to diagnose MDD; and (8) prevalence estimates were given with confidence intervals (CIs) and detailed by subgroups (if applicable). The total score ranges from 0 to 8. Studies with a total score of “7–8” were considered as “high quality,” “4–6” as “moderate quality,” and “0–3” as “low quality” (15).

Statistical Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 2.0 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). The random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled prevalence of suicidality and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) due to the different sampling methods and patients' demographic characteristics between studies. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed with the I2 statistic; I2 > 50% indicated high heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed to identify outlying studies by excluding studies one by one. Publication bias was estimated with funnel plots and the Egger test. A p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant (two-tailed).

Results

Characteristics of the Included Studies

One hundred seventy-eight full-text articles of the 9,192 studies initially identified in the literature search were assessed for eligibility. Fifteen studies fulfilled the entry criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1). Twelve studies assessed SA, five studies assessed SI, one study assessed SP, one study assessed unspecified suicidality (i.e., the subtype of suicidality was not specified), and two studies targeted only CS. The sample size ranged from 47 to 42,551; the mean ages ranged from 30.8 to 44.5 years (Table 1). Twelve studies were cross-sectional. Study quality assessment scores ranged from 3 to 7; 1 study was of low, 13 studies were of moderate, and 2 studies were of high quality (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| MDD group | Control group | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | First author | Reference | Publication year | Study location | Survey time | Mean age (years) | Total (n) | Diagnose | MDD (n) | Diagnose | Control (n) | Study design | Men (%) | Source of patients | Type of suicidality | Timeframe of suicidality | Quality assessment |

| 1 | Li | (17) | 1996 | China | 1988–1994 | 35.2 | 52 | CCMD-2 | 30 | Neurosis | 22 | Case–Control | 44.2 | Inpatients | SA | NA | 4 |

| 2 | Li | (20) | 2006 | China | NA | 49.93 | 5,802 | DSM-IV | 198 | Non-MDD | 5,584 | Cross-Sectional | 48.3 | Mixed | SA | Lifetime, last time | 6 |

| 3 | Soderholm | (21) | 2020 | Finland | NA | 30.8 | 81 | DSM-IV | 50 | BPD | 31 | Cohort | 35.8 | Outpatient | SA, SI, SB | Lifetime, recent | 6 |

| 4 | Salloum | (19) | 1995 | USA | NA | NA | 3,175 | DSM-III | 2,421 | AUD | 754 | Cross-Sectional | 40.1 | Mixed | SA | NA | 4 |

| 5 | Choi | (22) | 2019 | Korea | 2006−2007 | 44.5 | 12,324 | DSM-IV | 753 | Non-MDD | 11,571 | Cross-Sectional | 39.2 | Mixed | SA, SP, SI | Lifetime | 7 |

| 6 | Moffitt | (18) | 2007 | New Zealand | NA | NA | 425 | DSM-IV | 212 | Non-MDD | 213 | Retro- spective |

48.7 | Community | SA | NA | 6 |

| 7 | Holmstrand | (23) | 2008 | Sweden | NA | 43.4 | 116 | DSM-III | 81 | Dysthymia | 35 | Cross-Sectional | 36.2 | Mixed | SA, CS | Lifetime | 4 |

| 8 | Chen | (24) | 1996 | USA | NA | NA | 6,498 | DSM-III | 801 | Non-MDD | 5,697 | Cross-Sectional | 43.5 | NA | SA | Lifetime | 4 |

| 9 | Li | (25) | 2017 | China | 2016.3–2016.6 | 38.1 | 5,189 | DSM-IV | 190 | Non-MDD | 4,999 | Cross-Sectional | 33.8 | Outpatient | SI | Past month | 6 |

| 10 | Goldney | (26) | 2002 | Australia | NA | NA | 3,010 | DSM-IV | 205 | Non-MDD | 2,805 | Cross-Sectional | NA | Mixed | SI | Last 2 weeks | 4 |

| 11 | Sagud | (27) | 2020 | Croatia | NA | NA | 371 | DSM-IV | 178 | Non- psychiatric |

193 | Cross-Sectional | 32.9 | NA | SA | Lifetime | 4 |

| 12 | Ma | (28) | 2009 | China | 2003.4 | NA | 4,767 | CIDI | 153 | Non-MDD | 4,614 | Cross-Sectional | 45.9 | NA | SA | Lifetime | 6 |

| 13 | Bronisch | (16) | 1994 | Germany | 1974–1982 | NA | 360 | DSM-III | 54 | Non-MDD | 316 | Cohort | NA | Inpatients | SA | NA | 5 |

| 14 | Areen | (29) | 2021 | USA | 2018 | NA | 42,551 | DSM-5 | 6,999 | Non-MDD | 35,552 | Cross-Sectional | NA | Community | SA, SI | Past 1 year | 7 |

| 15 | Axelsson | (30) | 1992 | Sweden | NA | NA | 47 | DSM-III | 33 | Paranoid disorder | 14 | Cross-Sectional | 1 | Mixed | CS | Lifetime | 3 |

MDD, major depressive disorder; BPD, borderline personality disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; CIDI, Composite Interview Diagnostic Instrument; AUD, alcohol use disorder; NA, not available; CCMD-2, Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders.

Suicidal Ideation

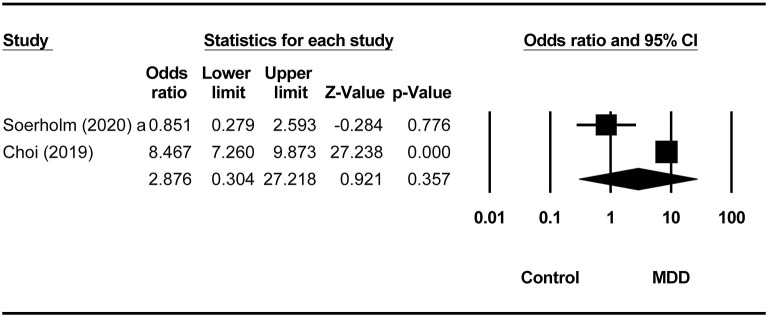

Compared to non-MDD controls, the odds ratios (ORs) for lifetime, past month, past year, and 2-week prevalence of SI in MDD were 2.88 (95% CI = 0.30–27.22, p = 0.36, I2 = 93.77%), 49.88 (95% CI = 2–8.63, p < 0.001, I2 = 0), 13.97 (95% CI = 12.67–15.41, p < 0.001, I2 = 0), and 24.81 (95% CI = 15.70–39.22, p < 0.001, I2 = 0), respectively (Figure 2). Compared to borderline personality disorder, no significant increase of SI was found in the MDD group (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 0.60–3.63, p = 0.40, I2 = 0) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation between the MDD group and non-MDD groups.

Table 2.

Summary of overall prevalence of suicide behaviors between the MDD group and non-MDD groups.

| MDD group | Non-MDD group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories (no. of studies) | Events | Total | Events | Total | OR | 95% CI (%) | p value | I 2 | |

| Suicide attempts | |||||||||

| Lifetime | 7 | 379 | 2,214 | 666 | 27,725 | 3.45 | (1.58–7.52) | 0.002 | 94.81 |

| Past year | 2 | 207 | 7,197 | 265 | 41,552 | 7.34 | (2.14–25.16) | 0.002 | 88.64 |

| Recent | 1 | 3 | 50 | 5 | 31 | 0.33 | (0.07–1.50) | 0.15 | 0 |

| Suicide ideation | |||||||||

| Lifetime | 2 | 451 | 803 | 1,470 | 11,602 | 2.88 | (0.30–27.22) | 0.36 | 93.77 |

| Recent | 1 | 29 | 50 | 15 | 31 | 1.47 | (0.60–3.63) | 0.40 | 0 |

| Past month | 1 | 67 | 190 | 54 | 4,999 | 49.88 | (33.42–74.46) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Past year | 1 | 1,409 | 6,999 | 630 | 35,552 | 13.97 | (12.67–15.41) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Past 2 weeks | 1 | 50 | 205 | 36 | 2,805 | 24.81 | (15.70–39.22) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Suicide plan | |||||||||

| Lifetime | 1 | 136 | 753 | 262 | 11,571 | 9.51 | (7.62–11.88) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Suicide behavior | |||||||||

| Lifetime | 1 | 12 | 50 | 20 | 31 | 0.17 | (0.06–0.46) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Recent | 1 | 8 | 50 | 8 | 31 | 0.55 | (0.18–1.65) | 0.29 | 0 |

| Completed suicide | |||||||||

| Lifetime | 2 | 10 | 114 | 6 | 49 | 0.69 | (0.23–2.02) | 0.50 | 0 |

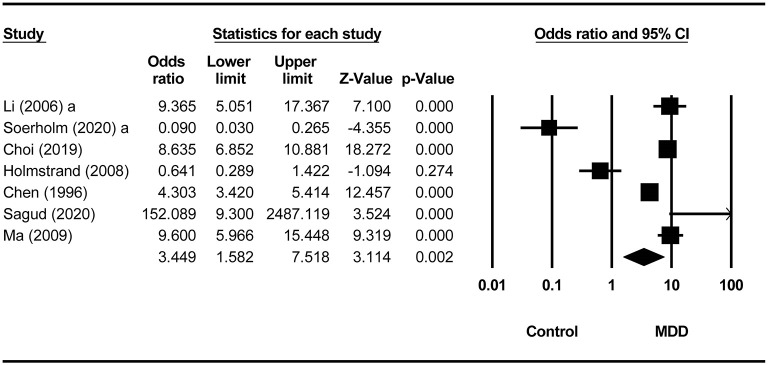

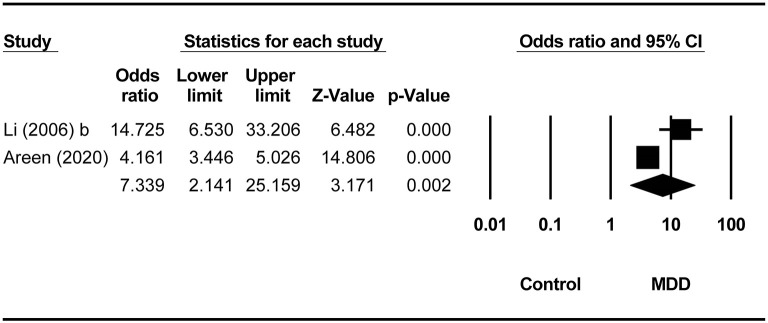

Suicide Attempt

Compared to non-MDD controls, the pooled ORs for lifetime and past-year SA in the MDD group were 3.45 (95% CI = 1.58–7.52, p = 0.002, I2 = 94.81%; Figure 3) and 7.34 (95% CI = 2.14–25.16, p = 0.002, I2 = 88.64%), respectively (Figure 4). There was no difference in the prevalence of recent SA between MDD and borderline personality disorder (OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.07–1.50, p = 0.15, I2 = 0). Four studies (16–19) did not report the timeframe of SA (Table 1). In the study by Salloum et al. (19), the prevalence of SA was 29.7% (719/2,421) in MDD, whereas the corresponding figure was 21.8% (164/754) in alcohol use disorder (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.25–1.85, p < 0.001). In the study by Li and Wang (17), the prevalence of SA was 33.3 % (10/30) in MDD, and it was 0 (0/20) in neurotic disorders (OR = 23.05, 95% CI = 1.27–418.67, p = 0.034). In the study by Moffitt et al. (18), the prevalence of SA was 3.7% (8/212) in MDD, whereas the corresponding figure was 0 (0/213) in the general population (OR = 17.75, 95% CI = 1.02–309.48, p = 0.049). Bronisch and Wittchen (16) found the prevalence of SA was 14.8% (8/54) in MDD and 1.9% (6/316) in the general population (OR = 8.99, 95% CI = 2.98–27.07, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Comparison of lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts between MDD and non-MDD groups.

Figure 4.

Comparison of 1-year prevalence of suicide attempts between the MDD and non-MDD groups.

SP and CS

Compared to non-MDD controls, the OR for lifetime SP in MDD was 9.51 (95% CI = 7.62–11.88, p < 0.001, I2 = 0). No difference in the prevalence of CS between MDD and controls was found (OR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.23–2.02, p = 0.50, I2 = 0). Two studies reported the lifetime CS (Table 1). Holmstrand et al. (23) reported the prevalence of CS was 9.9% (8/81) in MDD, and 14.3% in dysthymia (OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.20–2.17, p = 0.49). Axelsson and Lagerkvist-Briggs (30) found the prevalence of CS was 6.1 (2/33) in MDD and 7.1% (1/14) in delusional disorder (OR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.07–10.08, p = 0.89). Because of the small number of included studies, subgroup analysis and metaregression analyses could not be performed (Table 2).

Unspecified Suicidality

Compared to borderline personality disorder, MDD had a lower risk of lifetime suicidality (OR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.06–0.46, p < 0.001, I2 = 0), whereas no difference in the prevalence of recent suicidality between borderline personality disorder and MDD groups was found (OR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.18–1.65, p = 0.29, I2 = 0) (Table 2).

Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

The funnel plot of lifetime prevalence of SA did not show publication bias (Egger test: t = −2.37, p = 0.47; Supplementary Figure 1). After removing each study from studies reporting lifetime SA, no outlying study that could have significantly changed the primary results was found.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first meta-analysis and systematic review that compared the comprehensive range of suicidality between MDD and other psychiatric disorders and a healthy control group. Compared to non-MDD controls, MDD patients had a significantly higher risk of lifetime and past-year SA than non-MDD controls, which is consistent with previous findings that focused on psychotic MDD (9, 31). Non-MDD controls in this meta-analysis belonged to diverse diagnostic groups including borderline personality disorder, dysthymia, delusional disorder, and healthy persons.

The increased suicidality in MDD could be due to several reasons. Symptoms in MDD, such as feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness, delusionally depressive thoughts, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, directly and indirectly increase the risk of SA (32, 33). In addition, psychosocial factors associated with MDD, such as disruption of marital and family connections, could also increase the risk of suicidality (29, 33).

Suicidality lies on a continuum ranging from SI, SP, SA, to CS (34). Apart from sociocultural factors, the increased risk of suicidality in MDD could be associated with biological factors, such as the uncoupled N-acetylaspartate–glutamatergic metabolism in the anterior cingulate cortex (35) and the impaired executive functions and impulsivity control caused by decreased structural connectivity in the frontosubcortical circuit (36). Because of the limited number of studies on CS in MDD, the prevalence estimates of CS were not synthesized in this meta-analysis. Major risk factors for suicidality, particularly future CS in MDD, included severe depressive and psychotic symptoms (37, 38) and treatment resistance (39). The roles of these factors, however, were not explored in this meta-analysis owing to insufficient data in the included studies.

In this meta-analysis, the lifetime prevalence of SA was higher in borderline personality disorder than in MDD, which could be explained by the heightened sensitivity to abandonment, feelings of emptiness, and outbursts of anger, which are features of borderline personality disorder (40). Dysthymia also raises the frequency of suicidality (38, 41). In this systematic review, no significant differences in the prevalence of SA and CS between dysthymia and MDD were found, which is similar to previous findings (38, 41). Alcohol use disorder also has increased risk of suicidality (42). In this meta-analysis, the prevalence of SA in MDD was significantly higher than in alcohol use disorder.

Mental health professionals should integrate suicide prevention measures into clinical practice and devise effective communication channels designed to prevent suicide by changing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of MDD patients (33, 43–45). It is imperative to identify risk factors of suicidality in MDD, especially those that could accelerate the transition from SI and SP, to SA and to CS. It is also important to conduct regular screening targeting suicidality and risk factors in MDD (45).

Several limitations of the study should be noted. First, similar to many meta-analyses of comparative studies (9, 46, 47), a relatively high level of heterogeneity was encountered. Heterogeneity could be partly due to various types of controls, patient demographic characteristics, sampling methods, and measures on suicidality. Second, because of the small number of studies with each type of controls, subgroup analyses could not be performed to examine their moderating effect on the results. For the same reason, subgroup and metaregression analyses for each type of suicidality could not be performed. Third, most included studies had a case–control design; therefore, the possibility of recall bias about suicidality could not be excluded. Fourth, several moderators relevant to the prevalence of suicidality in MDD, such as age, gender, general health status, and social circumstances, could not be examined because of insufficient data.

In conclusion, MDD patients are at a higher risk of suicidality compared to diagnostically heterogeneous non-MDD controls. Considering the enormous suffering for patients and their relatives related to suicidality, as well as the negative impact of suicidality on health outcomes, regular screening for the whole range of suicidality should be included in clinical evaluation and management of MDD, and timely treatment should be provided for suicidal patients.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

Y-TX and LZ: study design. HC, X-MX, QZ, XC, and J-XL: collection, analyses, and interpretation of dat. HC, GU, and Y-TX: drafting of the manuscript. KS: critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approval of the final version for publication.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for investigational new drugs (2018ZX09201-014), the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Grant No. Z181100001518005), and the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.690130/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Mental Health-Suicide. WHO (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/health~topics/suicide#tab=tab_1 (accessed March 30, 2021).

- 2.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia classification algorithm of suicide assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA's pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. (2007) 164:1035–43. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke TA, Jacobucci R, Ammerman BA, Piccirillo M, McCloskey MS, Heimberg RG, et al. Identifying the relative importance of non-suicidal self-injury features in classifying suicidal ideation, plans, and behavior using exploratory data mining. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 262:175–83. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2011) 68:1058–64. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong M, Wang SB, Li Y, Xu DD, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of suicidal behaviors in patients with major depressive disorder in China: a comprehensive meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2018) 225:32–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong M, Zeng LN, Lu L, Li XH, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of suicide attempt in individuals with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of observational surveys. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:1691–704. 10.1017/S0033291718002301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Mol Psychiatry. (2010) 15:868–76. 10.1038/mp.2009.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suominen K, Haukka J, Valtonen HM, Lönnqvist J. Outcome of patients with major depressive disorder after serious suicide attempt. J Clin Psychiatry. (2009) 70:1372–8. 10.4088/JCP.09m05110blu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gournellis R, Tournikioti K, Touloumi G, Thomadakis C, Michalopoulou PG, Christodoulou C, et al. Psychotic (delusional) depression and suicidal attempts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2018) 137:18–29. 10.1111/acps.12826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA, (2000) 283, 2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association . DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: APA; (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines: World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle M. Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies. Evid Based Ment Health. (1998) 1, 37–39. 10.1136/ebmh.1.2.37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, Roberts JG, Stratford PW. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. (1998) 19:170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang C, Zhang L, Zhu P, Zhu C, Guo Q. The prevalence of tic disorders for children in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. (2016) 95:e4354. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bronisch T, Wittchen HU. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: comorbidity with depression, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (1994) 244:93–8. 10.1007/BF02193525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li HG, Wang Y. A clinical controlled study of depressive neurosis and depression. Sichuan Ment Health. (1996) 9, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Caspi A, Kim-Cohen J, Goldberg D, Gregory AM, et al. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: cumulative and sequential comorbidity in a birth cohort followed prospectively to age 32 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2007) 64:651–60. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salloum IM, Mezzich JE, Cornelius J, Day NL, Daley D, Kirisci L. Clinical profile of comorbid major depression and alcohol use disorders in an initial psychiatric evaluation. Compr Psychiatry. (1995) 36:260–6. 10.1016/S0010-440X(95)90070-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xianyun L, Wang Z, Wang S, Fei L. The characteristics of patients with major depression in non-psychological departments in general hospitals. China Mental Health. (2006) 20:4 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soderholm JJ, Socada JL, Rosenstrom T, Ekelund J, Isometsa ET. Borderline personality disorder with depression confers significant risk of suicidal behavior in mood disorder patients-a comparative study. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:290. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi KW, Na EJ, Hong JP, Cho MJ, Fava M, Mischoulon D, et al. Comparison of suicide attempts in individuals with major depressive disorder with and without history of subthreshold hypomania: a nationwide community sample of Korean adults()(,)(). J Affect Disord. (2019) 248:18–25. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmstrand C, Engstrom G, Traskman-Bendz L. Disentangling dysthymia from major depressive disorder in suicide attempters' suicidality, comorbidity and symptomatology. Nord J Psychiatry. (2008) 62:25–31. 10.1080/08039480801960164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry. (1996) 39:896–9. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00295-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Luo X, Ke X, Dai Q, Zheng W, Zhang C, et al. Major depressive disorder and suicide risk among adult outpatients at several general hospitals in a Chinese Han population. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0186143. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldney RD, Fisher LJ, Wilson DH, Cheok F. Mental health literacy of those with major depression and suicidal ideation: an impediment to help seeking. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2002) 32:394–403. 10.1521/suli.32.4.394.22343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sagud M, Tudor L, Simunic L, Jezernik D, Madzarac Z, Jaksic N, et al. Physical and social anhedonia are associated with suicidality in major depression, but not in schizophrenia. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2020) 51:403–15. 10.1111/sltb.12724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma X, Xiang YT, Cai ZJ, Li SR, Xiang YQ, Guo HL, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of major depressive episode in rural and urban areas of Beijing, China. J Affect Disord. (2009) 115:323–30. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omary A. Predictors and confounders of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adults with and without depression. Psychiatr Q. (2020) 92:331–45. 10.1007/s11126-020-09800-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Axelsson R, Lagerkvist-Briggs M. Factors predicting suicide in psychotic patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (1992) 241:259–66. 10.1007/BF02195974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zalpuri I, Rothschild AJ. Does psychosis increase the risk of suicide in patients with major depression? A systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2016) 198:23–31. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Quinn S, Parker G, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Brodaty H, et al. Predictors of suicide in major depressive disorder: a follow-up of patients seen at a specialist mood disorders unit. Acta Neuropsychiatr. (2006) 18:290. 10.1017/S.0924270800031276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamura K, Ikeshita K, Kimoto S, Makinodan M, Kishimoto T. Suicide prevention in Japan: Government and community measures, high-risk interventions. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. (2021) e12471. 10.1111/appy.12471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park EH, Hong N, Jon DI, Hong HJ, Jung MH. Past suicidal ideation as an independent risk factor for suicide behaviours in patients with depression. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. (2017) 21:24–8. 10.1080/13651501.2016.1249489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis CP, Port JD, Blacker CJ, Sonmez AI, Seewoo BJ, Leffler JM, et al. Altered anterior cingulate glutamatergic metabolism in depressed adolescents with current suicidal ideation. Transl Psychiatry. (2020) 10:119. 10.1038/s41398-020-0792-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myung W, Han CE, Fava M, Mischoulon D, Papakostas GI, Heo JY, et al. Reduced frontal-subcortical white matter connectivity in association with suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. (2016) 6:e835. 10.1038/tp.2016.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holma KM, Melartin TK, Haukka J, Holma IA, Sokero TP, Isometsä ET. Incidence and predictors of suicide attempts in DSM–IV major depressive disorder: a five-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. (2010) 167:801–8. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witte TK, Timmons KA, Fink E, Smith AR, Joiner TE. Do major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder confer differential risk for suicide? J Affect Disord. (2009) 115:69–78. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I, Bailer U, Bollen J, Demyttenaere K, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a European multicenter study. J. Clin. Psychiatry. (2007) 68:1062–70. 10.4088/JCP.v68n0713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levy KN. The implications of attachment theory and research for understanding borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol. (2005) 17:959–86. 10.1017/S0954579405050455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L. Suicidal risks in 12 DSM-5 psychiatric disorders. J Affect Disord. (2020) 271:66–73. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darvishi N, Farhadi M, Haghtalab T, Poorolajal J. Alcohol-related risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0126870. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service . National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Michigan: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vijayakumar L, Ray S, Fernandes TN, Pathare S. A descriptive mapping review of suicide in vulnerable populations in low and middle countries. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. (2021) 13:e12472. 10.1111/appy.12472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization . Public Health Action for the Prevention of Suicide: A Framework. WHO: (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purtle J, Nelson KL, Yang Y, Langellier B, Stankov I, Diez Roux AV. Urban-Rural differences in older adult depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 56:603–13. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solmi M, Zaninotto L, Toffanin T, Veronese N, Lin K, Stubbs B, et al. A comparative meta-analysis of TEMPS scores across mood disorder patients, their first-degree relatives, healthy controls, and other psychiatric disorders. J Affect Disord. (2016) 196:32–46. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.