Abstract

Evidence is sparse when it comes to the longitudinal impact of educational interventions on empathy among clinicians. Additionally, most available research on empathy is on medical trainee cohorts. We set out to study the impact of empathy and communication training on practicing clinicians’ self-reported empathy and whether it can be sustained over six months. An immersive curriculum was designed to teach empathy and communication skills, which entailed experiential learning with simulated encounters and didactics on the foundational elements of communication. Self-reported Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) was scored before and at two points (1–4 weeks and 6 months) after the training. Overall, clinicians’ mean self-empathy scores increased following the workshop and were sustained at six months. Specifically, the perspective taking domain of the empathy scale, which relates to cognitive empathy, showed the most responsiveness to educational interventions. Our analysis shows that a structured and immersive training curriculum centered on building communication and empathy skills has the potential to positively impact clinician empathy and sustain self-reported empathy scores among practicing clinicians.

Keywords: empathy, communication, patient/relationship-centered skills, relationships in healthcare, connections

Introduction

Background

Cultivating connection with patients is foundational to a therapeutic relationship and patient-centered care. Empathy, “the act of correctly acknowledging the emotional state of another without experiencing that state oneself”1 is an essential element that fuels connection and fosters a relationship. In times of acute or serious illness, empathetic communication becomes even more crucial.2–4 This paper describes a novel communication and empathy workshop and evaluates its ability to enhance clinician empathy.

Building skills in empathetic communication among clinicians has many advantages for patients as well as for clinicians. Empathetic communication has been shown to correlate with greater diagnostic accuracy.5 An empathetic clinician is able to more readily elicit pertinent information and relevant psychosocial concerns from patients.6,7 Additionally, empathy enables a clinician to relate with patients and better understand their needs.8 Tailored communication that meets patients’ where they are at, empowers them to participate in decision-making.9,10 These positive effects of clinical empathy translate into improvements in patient satisfaction, patient empowerment, and adherence with proposed treatment plans.11,12

Evidence suggests that having empathy is a positive predictor of clinical competence in medical trainees.13,14 Empathy in clinicians is also perceived as a mark of competence by their patients.15 Not surprisingly, empathy is considered to be a major element of professionalism in medicine16 and an important attribute of the humanistic physician.17

In addition to the myriad of direct patient benefits that clinician empathy provides, the ability to form meaningful connections, being attuned to a patient’s emotions, and empathize with them are some of the core elements that contribute to professional satisfaction as well. A growing body of the literature supports the idea that empathetic clinicians experience fewer burnout symptoms.18 Recent studies suggest that over half of physicians in the United States show evidence of burnout,19 bringing it to a crisis level even prior to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, promoting and sustaining empathy among healthcare providers is more important than ever.

Proficiency in patient-centered care is considered a gold standard in medicine.20 Fostering clinical empathy in trainees is a goal of medical education and is endorsed by professional medical organizations. A 2001 expert consensus statement outlined a comprehensive set of essential communication elements for physicians.21 In this statement, “understanding patient perspective” was highlighted as an essential element. However, there is currently a gap in communication skills and empathy training for physicians22 with no clear consensus on how best to teach these skills within a curriculum.

Although it is commonly thought that the ability to relate empathetically to others is a trait or talent that some possess and others do not, studies show that empathy skills can be taught23 and significantly improved,24,25 particularly if taught through experiential learning.26,27 Significant and sustained improvements in empathy in nurses were demonstrated after a robust nine-week program comprised of self-directed study, regular meetings with a supervisor, a two-day workshop, and supervised clinical work.28 A systematic review by Baugh et al. that looked into the long-term effectiveness of empathic interventions in medical education found that empathy declined over time.29 There is a paucity of evidence in the medical literature to support the idea that clinical empathy can be improved and sustained following educational interventions. We created a communication and empathy curriculum for practicing clinicians and studied its impact on a sustained improvement in provider empathy.

Empathy Curriculum Development

The medical literature gives us multiple examples of behaviors that can be considered “empathetic”. However, from a curricular development standpoint, the real challenge lies in improving empathy and transforming clinicians’ mindsets. Empathy is a complex and multidimensional process which is commonly defined as a psychological process that encompasses three mechanisms: affective, cognitive, and behavioral.30 Irving and Dickson proposed treating empathy as an attitude.31 They theorized that the behavioral dimension of empathy can be cultivated as a “skill”. This skill reflects acknowledgement of the expressed emotions of another, cognitive appraisal and responding with empathy. This idea suggests that the inner capacity to empathize can be expressed as an observable behavioral skill.

Barrett-Lennard developed a multidimensional model of clinical empathy, referring it as an “empathy cycle,” consisting of three phases.32 Phase 1 is the inner process of empathetic listening with the intent to understand the emotional state of the other person. Phase 2 is a response to expressed emotion and to verbalize an empathetic understanding of their experience. Phase 3 is the reception or awareness of this response by that person. It is this three-phase model that was our organizing principle in designing our empathy curriculum, which we refer to as “CRAVE” (Communication, Resilience, Authenticity, Vulnerability, and Empathy).

Aim

The main objective of this study was to determine the impact of the CRAVE training on self-reported clinician empathy scores. Specifically, our research question was whether a structured communication and empathy workshop can increase the empathy of practicing clinicians, and whether any increase could be sustained over six months after the educational intervention.

Methods

CRAVE

The CRAVE course is a full-day communication and empathy training based on experiential learning. It includes a combination of simulated patient actor encounters based on the VitalTalkTM framework, as well as didactic lectures. VitalTalkTM is a nonprofit company which grew from NIH-funded research on the development of courses to improve communications skills among clinicians.33 The didactics in our workshop included short, interactive lectures on listening, delivering information, impact of verbal and nonverbal communication, neurobiology of emotion, and the concept of empathy as a learned skill. This curriculum was designed by two hospital medicine physicians in a large Midwestern healthcare system and offered to the system clinicians two to three times per year. Course availability was advertised via email and department meetings. Participation in the course was free of charge and voluntary; however, no protected time was offered for attendance. The interactive sessions were designed for a maximum of six participants with professional actors playing the role of patients or family members in one of four case scenarios. The actors embodied fully developed characters with an in-depth back story and strong emotions but were not given a script. These simulations created challenging and emotionally charged clinical situations that required the application of empathetic communication skills to navigate them. Every learner in the group participated in a faculty-moderated encounter with the patient or family member. Since these encounters required clinicians to “perform” in front of their peers, deliberate care was taken to create psychological safety, where participants could be vulnerable while navigating these challenging scenarios and trying out new skills. In each group of six, one engaged in the encounter, the other five observed, ensuring active engagement and learning for all. Each encounter included a debrief consisting of positive feedback from the peers as well as the participants’ self-reflection. A repeat attempt was offered after the debrief to practice and consolidate the skills. Each learner engaged in two scenarios during the two (morning and afternoon) sessions.

An example of a case scenario is detailed in Appendix 1.

Study Design

This longitudinal study examined the impact of the CRAVE curriculum on self-reported clinician empathy. Self-evaluation surveys were collected from the clinicians before, shortly after, and six months after the CRAVE workshop. Self-rated empathy was measured using the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSE). This scale is an operational self-reported measure of empathy, specifically applicable to medical care. Developed by Hojat et al.,34 it has been translated into 56 languages and used in more than 80 countries. It is considered to be a standard empathy scale in a medical context.35 The JSE is a 20-item instrument answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). Half of the items are positively worded and directly scored, and the other half are negatively worded and scored in reverse. Each question on the JSE gauges one of three domains: perspective taking, compassionate care, and standing/walking in the patient’s shoes. Three versions of the JSE are available; we used the version targeted to practicing health professionals.

Data Collection

Between October 2018 and November 2019, the CRAVE course was offered four times. We surveyed clinicians via self-evaluation 1–4 weeks prior to participation in the CRAVE course, 1–4 weeks after CRAVE, and 6 months after (± 3 weeks). Institutional review board approval was received prior to the study. Upon enrollment in the course, research staff screened the participants for inclusion/exclusion criteria. To be included, clinicians had to be an MD, NP, PA-C, MBBS, or DO; have scheduled rotation at the hospital where data collection was conducted; and consent to be in the study. A research intern contacted participants and collected the survey. Due to budget constraints, this intern was only able to contact clinicians at one of the hospitals in the health system. Participants received baseline surveys, including a demographic questionnaire and the initial JSE, 1–4 weeks prior to the CRAVE course. They repeated the JSE at 1–4 weeks and again 6 months after the course. All clinicians who met inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. Twenty clinicians who enrolled in the course consented to participate in the study, completed the preworkshop survey, and attended the course. Sixteen clinicians completed the presurveys and at least one postcourse survey (either 4 weeks or at 6 months). Fourteen providers completed all three, the pre- and postcourse survey plus an additional postcourse survey at 6 months. There was a six-month loss of follow up for two providers related to the pandemic.

Results

Of the course registrants who consented to our study, one was unable to attend the CRAVE course. Due to schedule changes, three did not do clinical rotations at the study hospital at 1–4 weeks after the course, and one was not on rotation in the 6-month data collection window. Two providers who completed the baseline surveys did not complete surveys at 1–4 weeks, but did complete them at six months. One opted not to complete the JSE at 6 months.

The baseline characteristics of study population (Table 1) showed a predominant representation of females (70%) compared to males (30%). The mix of clinicians was comprised of seventy percent (70%) MD/DO, ten percent (10%) NP, and twenty percent (20%) PA-C. Ninety percent of study participants were internists, all practicing in acute care settings. One of the participants (5%, N = 1) practiced Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and one (5%, N = 1) practiced palliative care.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants.

| N = 20 who attended the workshop and completed surveys for at least one time point | N = 14 who attended the workshop and completed surveys for all three time points | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Female | 14 | 70 | 10 | 71 |

| Male | 6 | 30 | 4 | 29 |

| MD/DO | 14 | 70 | 10 | 71 |

| NP | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| PA-C | 4 | 20 | 4 | 29 |

| Internal medicine | 18 | 90 | 13 | 93 |

| Palliative care | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Physical medicine and rehab | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| 21–30 years of age | 7 | 35 | 5 | 36 |

| 31–40 years of age | 8 | 40 | 5 | 36 |

| 41–50 years of age | 4 | 20 | 3 | 21 |

| 51–60 years of age | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

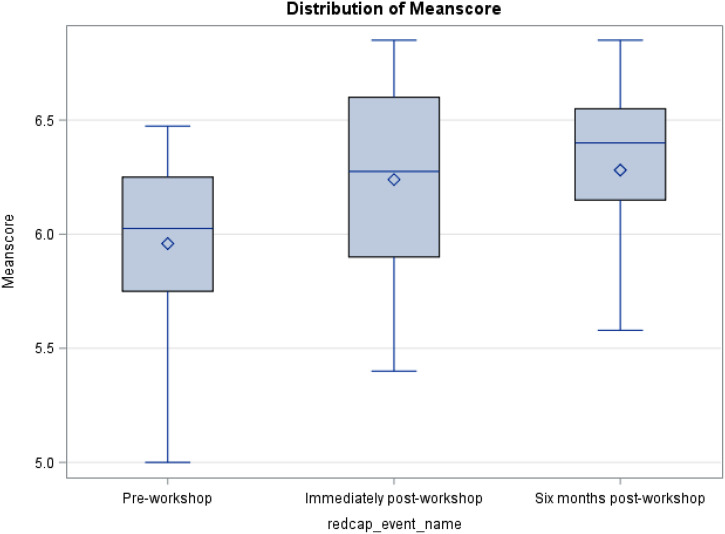

For the 14 providers who completed surveys at all three time points, a matched pairs ANOVA (analysis of variance) suggests mean empathy increased from pre- to postcourse and again at 6 months postcourse (p = 0.09). The mean empathy scores at all three time points is shown in Figure 1. When broken out, none of the three domains (compassion, perspective taking, and ability to walk in patients’ shoes), were significant for change over time (p = 0.13, 0.29, and 0.23, respectively). Table 2 shows the difference in mean empathy scores, overall and by domain, at three time points for N = 14 matched pairs.

Figure 1.

Mean empathy scores at all three time points (N = 14).

Table 2.

Difference in Mean Empathy Scores, Overall and by Domain, at Three Time Points for N = 14 Matched Pairs.

| T1 mean (SD) | T2 mean (SD) | T3 mean (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall empathy score | 5.96 (0.40) | 6.24 (0.45) | 6.28 (0.37) | 0.09 |

| Compassion score | 6.22 (0.49) | 6.47 (0.37) | 6.54 (0.41) | 0.13 |

| Perspective score | 5.97 (0.47) | 6.19 (0.57) | 6.27 (0.36) | 0.29 |

| Walking in shoes score | 5.14 (1.02) | 5.61 (0.89) | 5.60 (0.78) | 0.23 |

An ANOVA was run on all 52 data points (20 mean scores at baseline; 16 postcourse, and 16 at 6 months), without accounting for nonindependence of data points. That is, the mean empathy score of the 20 providers who completed the presurvey was compared with the mean empathy score of the 16 providers who completed the (1–4 week) postsurveys and the 16 providers who completed surveys at 6 months. In this analysis, overall empathy score was significant for change in mean over time (p = 0.02). When analyzed by domain, perspective score was significant (p = 0.02), but neither compassion nor walking in patients’ shoes reached significance. Table 3 shows the difference in mean empathy scores, overall and by domain, at three time points, for N = 52 independent data points.

Table 3.

Difference in Mean Empathy Scores, Overall and by Domain, at Three Time Points, for N = 52 Independent Data Points.

| T1 mean (SD) | T2 mean (SD) | T3 mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 20 | n = 16 | n = 16 | p-value | |

| Overall empathy score | 5.94 (0.39) | 6.21 (0.45) | 6.30 (0.35) | 0.02 |

| Compassion score | 6.24 (0.54) | 6.43 (0.47) | 6.57 (0.46) | 0.12 |

| Perspective score | 5.89 (0.43) | 6.16 (0.56) | 6.28 (0.33) | 0.02 |

| Walking in shoes score | 5.25 (0.97) | 5.67 (0.84) | 5.65 (0.75) | 0.27 |

Discussion

We set out to evaluate the impact of a communication and empathy workshop on improving clinician empathy and whether this course would lead to a durable change in self-assessed empathy at six months.

Our analysis showed that the clinicians’ mean self-empathy scores increased after the CRAVE course, and this increase was sustained over 6 months. The mean score showed an upward trend over time (5.96 vs. 6.24 vs. 6.28), and statistical significance was approached (p = 0.09).We believe this trend toward significance is promising, but not yet conclusive given the small sample size in this study. When broken out by domains of empathy (compassionate care, perspective taking, and the ability to walk in patients’ shoes), no individual domain reached significance; again, this could be related to small sample size and a more highly powered study may be needed to detect true differences.

We also performed an exploratory analysis using ANOVA at all data/time points, regardless of whether providers completed all three time points. This exploratory analysis was done not to draw conclusions but rather to generate hypotheses for statistically valid research in the future. This analysis shows an increase in mean empathy score over time (5.94 vs. 6.21 vs. 6.30; p = 0.02). When broken out by domain, mean perspective scores reached significance (5.89 vs. 6.16 vs. 6.28; p = 0.02).

Advances in neurosciences have refined our understanding of the concept of empathy. A clinician’s empathy within patient care context is predominantly cognitive rather than affective. Cognitive empathy involves understanding rather than feeling with patients (their suffering, pain or other emotions) and most importantly, combines it with the capacity to communicate this understanding with the intention to help.34,35 Our exploratory analysis showed that the perspective taking domain, i.e., cognitive empathy, arguably the most important for clinicians, is most susceptible to training and can be improved in clinicians. Research consistently supports the concept that individuals with a greater cognitive role-taking capacity or higher dispositional empathic concern can communicate better than those with lower capacity.36 There are few studies with focused curricula that have explored the perspective taking domain of clinician empathy.37,38 Emotion and cognition are integral to relational skills and making connections. While the components of empathy (affective, cognitive, and behavioral) are deemed independent, they are also deeply interwoven. Too much affective empathy (feeling others’ pain) can lead to compassion fatigue and burnout. It is often advised to regulate this component of empathy. Our curriculum, through experiential learning, showed promise to improve participants’ capacity of perspective taking and gain understanding of others subjective experiences.

This study also examined whether the impact of empathy training could be sustained over time. Evidence is sparse when it comes to the longitudinal impact of training on empathy. At present, only a few studies have explored the long-term impact of empathy training.39–41 A systematic review challenged the idea of sustained improvement in empathy of medical trainees by educational interventions.29 Our study showed that the overall mean empathy scores improved after the training and this trend was maintained at six months. Studies have shown that the participants with high initial empathy scores have the least longitudinal declines.42 Although not conclusively proven, the available evidence suggest that females have higher baseline scores, show greater susceptibility to increase in empathy from intervention and have slower/smaller decline in empathy over time as compared to male cohorts.29 In our study, 70% of the participants were females which may influence our findings.

Most available research studying the impact of empathy training comes from medical trainee cohorts, while there is a paucity of research studying the impact of empathy training on practicing clinicians.43 Creating a quality curriculum to enhance empathy that is also accessible to busy practicing clinicians is challenging. Practicing clinicians can become “set in their ways.” Once out of training, work stressors and time demands can further erode a sense of service, humility and lifelong learning. This can lead to clinician-patient relations becoming more transactional in nature, with less interpersonal connection that may increase burnout. These same time demands, whether personal or professional, can also make it difficult to create time space for learning. A single day training is more feasible and time-efficient than trainings which involve multiple day commitments and touch-points. A thoughtful, immersive and experiential training like ours, tailored to the clinical practice and delivered in a single day may enhance and sustain empathy over time. This study also supports the idea of continuous learning of empathy skills for clinicians throughout their careers. These trainings might act as empathy skill building “gyms”, often invigorating a sense of purpose and renewed sense of connection. These connections with patients are often a source of joy in our work lives.

Our analysis shows that educational interventions positively impact clinician empathy and that a structured and immersive training curriculum has the potential to increase and sustain self-reported empathy scores for clinicians. Further studies with a larger sample size are warranted to fully measure the impact of this work.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study was statistical power, which is largely due to a low number of providers who were able to attend the CRAVE training and complete surveys at all three time points. Our study was powered for N = 20; however, only 14 clinicians completed surveys at all three data points. Although our first analysis, which used 14 matched pairs, was statistically valid, our second analysis was not, as it did not account for nonindependence of data points and should not be used to make any conclusions. Data collection was limited to providers who practice at a single hospital within one care system, although providers from other sites within this care system did attend the training. We were forced to halt data collection in March 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which further winnowed the participants. Data was self-reported and does not take into account the patient’s perception of provider’s empathy and communication. The designed empathy curriculum, although based on widely available concepts of teaching empathy was specific and tailored, so it is possible generalizability may be limited. Lastly, this study was conducted at a single institution with a small sample size of volunteer clinicians which may add selection bias of clinicians who are especially receptive to such educational interventions.

Conclusion

The CRAVE training curriculum was designed to translate clinician’s inner capacity to empathize into actionable skills. Our analysis supports the effectiveness of this training on clinician self-perception of their empathy skills, thus making the case for integration of such training for practicing clinicians. Clinician mean self-empathy scores increased after the CRAVE training, and this increase was seen mostly in the perspective taking domain that relates to cognitive empathy. This increase in empathy score was sustained over 6 months; however, it did not reach statistical significance due to small sample size. These results are intended to inform the implementation and evaluation of empathy curricula for continuing medical education. Further research is needed on clinician empathy training interventions including their effects across domains and the endurance of their impact.

Acknowledgments

John Dressen, William Bekker, Alex Holsman, and Shauna Baer for supporting our empathy endeavors.

Appendix 1.

| Case Story | Session 1 | Learning Objectives | Session 2 | Learning Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78-year-old man with a history of dementia, COPD, chronic kidney disease, peripheral vascular and coronary artery disease with recurrent admissions due to COPD exacerbations and aspiration pneumonia was admitted to the hospital a week ago for sepsis due to pneumonia, initially requiring BIPAP support and complicated by acute kidney injury that resolved. He is now transitioned to nasal canula for oxygen support. Despite supportive cares, he remains intermittently arousable. Extensive workup has not revealed any specific cause of the altered mental status. A speech evaluation showed aspiration. He remains tube feed dependent. You are taking over the service today. The limiting factors for his discharge are ongoing artificial nutrition and general goals of care with his daughter with whom he lives. | Instructions to the Learner: Discuss goals of care with the daughter regarding artificial nutrition and the patient’s advanced dementia with this presumed new baseline. Challenges: Strong emotions of daughter remain a hurdle (Cynical, angry and indignant). | Address the emotions of the daughter before the conversation can progress. Emotional cues are potential empathetic opportunities. | Instructions to the Learner: Discuss prognosis and make recommendations regarding the plan of care. Challenges:1 Daughter remains resistant, feeling that she is “giving up” on her father. | Explore patient’s values (via healthcare proxy) before making any recommendations. Recognize the daughter’s emotions throughout the encounter and respond with empathy. |

It may improve readability if there is a break in line between "instructions to the learner" and "challenges" in session 1 and 2 subheadings

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to report this research was obtained from the HealthPartners Institute’s Institutional Review Board ID-A18-007

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the HealthPartners Institute’s Institutional Review Board ID-A18-007

Statement of Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ankit Mehta https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5012-6048

References

- 1.Markakis K, Frankel R, Beckman H, Suchman A: Teaching empathy: it can be done. Working paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, San Francisco, CA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nutting PA, Goodwin MA, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC. Continuity of primary care: to whom does it matter and when? Ann Fam Med. 2003;1:149-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hruby M, Pantilat SZ, Lo B. How do patients view the role of the primary care physician in inpatient care? Am J Med. 2001;111:21S-5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schers H, van de Ven C, van den Hoogen H, Grol R, van den Bosch W. Patients’ needs for contact with their GP at the time of hospital admission and other life events: a quantitative and qualitative exploration. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:462-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The effect of physician behaviour on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulehan JL, Platt FW, Egener B, Frankel R, Lin CT, Lown B, et al. “Let me see if I have this right…”: words that help build empathy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Squier RW. A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationships. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:325-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews DA, Suchman AL, Branch WT, Jr. Making “connexions”: enhancing the therapeutic potential of patient-clinician relationships. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118:973-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suchman AL, Roter D, Green M, Lipkin M, Jr. Physician satisfaction with primary care office visits. Collaborative study group of the American academy on physician and patient. Med Care 1993; 31: 1083-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercer SW. Reynolds WJ: empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(suppl):S9–S12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27:237-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertakis KD, Roter D, Putnam SM. The relationship of physician medical interview style to patient satisfaction. J Fam Pract. 1991;32:175-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Veloski JJ, Erdmann JB, et al. Empathy in medical students as related to academic performance, clinical competence and gender. Med Educ. 2002a;36:522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hojat M, Erdmann JB, Gonnella JS. Personality assessments and outcomes in medical education and the practice of medicine (AMEE Guide 79). Dundee: Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE); 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogle J, Bushnell JA, Caputi P. Empathy is related to clinical competence in medical care. Med Educ. 2013;47:824-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veloski J, Hojat M. Measuring specific elements of professionalism: empathy, teamwork, and lifelong learning. In: Stern DT. (ed) Measuring medical professionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006, pp.117-45. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linn LS, DiMatteo MR, Cope DW, Robbins A. Measuring physicians’ humanistic attitudes, values, and behaviors. Med Care. 1987;25:504-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuguero O, Forne C, Esquerda M, Pifarre J, Abadias MJ, Vinas J. Empathy and burnout of emergency professionals of a health region: a cross-sectional study. Medicine 2017;96(37):e8030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011-2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine. Health professions education: a bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76:390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tulsky JA. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiro H. What is empathy and can it be taught? Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(10):843–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winefield HR, Chur-Hanson A. Evaluating the outcome of communication skill teaching for entry-level medical students: does knowledge of empathy increase? Med Ed. 2000;34:90-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer D, Ber R, Morre M. Increasing empathy among medical students. Med Ed. 1989;23:168-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Branch WT, Jr, Kern D, Haidet P, Weissmann P, Gracey CF, Mitchell G, et al. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA 2001;286(9):1067-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds W. The measurement and development of empathy in nursing. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baugh RF, Hoogland MA, Baugh AD. The long-term effectiveness of empathic interventions in medical education: a systematic review. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020 Nov 20;11:879-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog Select Documents Psychol. 1980;10:85. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irving P, Dickson D. Empathy: towards a conceptual framework for health professionals. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2004;17:212-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barret-Lennard GT. The empathy cycle; refinement of a nuclear concept. J Counsel Psychol. 1981;28:91-100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.https://www.vitaltalk.org.

- 34.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Cohen MJM, Gonnella JS, Erdmann JB, et al. The jefferson scale of empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Measure. 2001;61:349-65. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hojat M. Empathy in health professions education and patient care. New York: Springer International; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson EB, Yao X.. et al. Clinical empathy as emotional labor in patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 2005;293(9):1100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim BT, Moriarty H, Huthwaite M. “Being-in-role”: a teaching innovation to enhance empathic communication skills in medical students. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):e663-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu J, Lee S, Kim M, Lim K, Chang K, Lee M. Relationships between perspective-taking, empathic concern, and self-rating of empathy as a physician Among medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(3):316-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meadows A, Higgs S, Burke SE, Dovidio JF, van Ryan M, Phelan SM. Social dominance orientation, dispositional empathy, and need for cognitive closure moderate the impact of empathy-skills training, but not patient contact, on medical students’ negative attitudes toward higher-weight patients. Front Psychol. 2017;8:504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kataoka H, Iwase T, Ogawa H, Mahmood S, Sato M, DeSantis J, et al. Can communication skills training improve empathy? A six-year longitudinal study of medical students in Japan. Med Teach. 2019;41(2):195-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca S, Nasca TJ, Gonnella JS, Magee M. Empathy scores in medical school and ratings of empathic behavior in residency training 3 years later. J Soc Psychol. 2005;145(6):663-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen DCR, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, Kirshenbaum E, Aseltine RH. Characterizing changes in student empathy through- out medical school. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):305-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misra-Hebert AD, Isaacson JH, Kohn M, Hull AL, Hojat M, Papp KK, et al. “Improving empathy of physicians through guided reflective writing” (2012). Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior Faculty Papers. Paper 51.