Abstract

Aims:

Total and free testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin may affect cardiovascular prognosis in women. The objective was to study the association between sex hormones and prognosis in women with dysglycemia and high cardiovascular risk.

Methods:

This epidemiological report included dysglycemic women from the Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention trial (n = 2848) with baseline total testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin. Free testosterone was calculated with the Vermeulen formula. Cox regression analyses adjusted for variables including age, previous diseases and pharmacological treatments were used to estimate the association between these levels and the composite cardiovascular outcome (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke) and all-cause mortality per one standard deviation.

Results:

Patients (73% post-menopausal) were followed for a median of 6.1 years during which 377 cardiovascular events and 389 deaths occurred. In Cox analyses, total and free testosterone were not associated with any outcomes, but sex hormone-binding globulin was related to all-cause mortality in age adjusted (HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.06–1.24; p < 0.01) and fully adjusted analyses (HR 1.14; 95% CI 1.05–1.24; p < 0.01).

Conclusions:

Increasing levels of baseline sex hormone-binding globulin were associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality in dysglycemic women at high cardiovascular risk.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov no. NCT00069784.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, diabetes, prognosis, sex hormone-binding globulin, testosterone, women

Introduction

The importance of sex hormones in the development of cardiovascular disease in women has been debated. Whereas the focus has traditionally been on estrogen,1 the importance of testosterone and its binding protein sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) has attracted recent attention.2 Testosterone acts both as an androgen and as a precursor of estradiol and exerts important physiological effects on well-being, sexual function, bone metabolism and cardiometabolic health.3 Studies in women of reproductive age and with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a condition typically characterized by hyperandrogenism (high testosterone levels) and hyperinsulinemia, have suggested an increased risk of developing cardiovascular risk factors however the effects on cardiovascular mortality is unclear.4,5 To what extent testosterone is related to prognosis in middle-aged and elderly women with dysglycemia remains to be clarified.

The level of free testosterone is in part regulated by SHBG. High levels of the latter can result in lower fractions of free testosterone. Whereas some observational studies have reported that cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality and diabetes are associated with low levels of total and free testosterone as well as SHBG6–8 others have related some of these outcomes to high levels.2,9,10 These inconsistent results illustrate the importance of further research to elucidate the relationship between androgens and cardiovascular disease in women.

The present study investigates the prognostic impact of testosterone and SHBG on the development of cardiovascular outcomes in female participants in the Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial11 comprising a well-defined cohort of dysglycemic patients at high cardiovascular risk.

Material and methods

As previously published, participants in ORIGIN comprised 12,537 men (65%) and women (35%) ⩾50 years with either prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance) or type 2 diabetes and additional cardiovascular risk factors. They were randomly assigned to insulin glargine (Gla-100) vs. standard care and either omega 3 fatty acids vs. placebo using a 2 × 2 factorial design.11,12 Exclusion criteria included serious comorbid conditions such as active cancer, hepatic cirrhosis, chronic or recurrent treatment with systemic corticosteroids or an expected survival of less than 3 years by non-cardiovascular causes. During a median follow up time of 6.1 years, patients were followed for a composite outcome of cardiovascular events including cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke.11,12 A secondary outcome was all-cause mortality. Research Ethics Boards approved the ORIGIN trial in all study centres.

A subset of participants also consented to the collection and storage of blood samples for future measurement of cardiovascular risk factors. They were included in a biomarker study in which 8494 participants had biomarkers measured as outlined below and following elimination of unanalyzable and undetectable biomarkers, the total population was comprised of 8401 participants (34% women).13 The present study comprises female participants of this subset in whom total testosterone and SHBG were assayed (n = 2848).

Laboratory analyses

Fasting blood samples at baseline were collected, divided into aliquots and transported to the Population Health Research Institute biobank in Hamilton for storage in nitrogen vapor-cooled tanks at −160°C. Following completion of the ORIGIN trial, coded aliquots of serum from each study participant were transported to Myriad RBM Inc (Austin, Texas). In a biomarker substudy, multiplex analysis of a predefined panel of 284 biomarkers was performed using a customized Human Discovery Multi-Analyte Profile (MAP) 250 + panel on the LUMINEX 100/200 platforms. The biomarker results were carefully scrutinized, leaving a total of 237 reported biomarkers from 8401 participants in the final dataset. This included total testosterone, SHBG and luteinizing hormone (LH) which had inter-run coefficients of variation at intermediate concentrations at 7%, 14% and 6% respectively.13 Estradiol was not available in the database.

Definitions

Free testosterone was calculated according to the Vermeulen et al.14 formula with a fixed albumin concentration of 43 g/L.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were presented as means (standard deviation [SD]) and compared using t-test, categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentage (%) and compared using chi-square test. The relationship between levels and outcomes were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated per an increase of one SD for continuous variables. In multivariate models, Model A was adjusted for age; Model B was further adjusted for log-transformed LH levels (which regulates the production of testosterone), previous cardiovascular disease, previous diabetes, use of metformin, use of statins, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, body mass index and smoking; and Model C was further adjusted for menopausal status, hormone treatment, alcohol consumption, ethnicity, obstructive sleep apnea and thyroid drugs. Whether the estimates differed according to allocated treatment group or previously established CVD was assessed by testing for interactions. Previously established CVD was defined as prior MI, stroke, revascularisation, or angina with documented ischemia compared to high CV risk which was defined as morning urinary albumin/creatinine ratio >30 µg/mg, evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy, 50% stenosis of a coronary, carotid or lower extremity artery documented angiographically and/or an ankle/brachial index <0.9. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was used as a nominal level of significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Clinical characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the study cohort are outlined in Table 1. A total of 2848 women of mean age 64 years whereof 73% were post-menopausal with either prediabetes (16%) or diabetes (84%) were included. Previous cardiovascular events (including myocardial infarction, stroke and revascularisation) were reported by 43%, and 23% reported a previous myocardial infarction. Mean (SD) BMI was 31.1 (6.2) kg/m2, mean (SD) total cholesterol was 5.2 (1.2) mmol/L and mean (SD) HbA1c was 6.6 (1.0)% (IFFS 49 mmol/mol). Statins were used in 44% of the patients, aspirin in 56% and ACE-inhibitors/ARB in 69%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants. Continuous variables presented as mean (standard deviation) and categorical variables presented as n (%).

| All participants n = 2848 | |

|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 64.0 (8.0) |

| Known diabetes | 2399 (84.2) |

| Newly detected diabetes | 150 (5.3) |

| Newly detected IGT/IFG | 298 (10.5) |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 5.4 (5.9) |

| Previous cardiovascular events | 1228 (43.1) |

| Myocardial infarction | 640 (22.5) |

| Hypertension | 2419 (84.9) |

| Smoker | 296 (10.4) |

| Alcohol consumption >2 drinks/week | 218 (7.7) |

| Menopause | 2086 (73.2) |

| Menopause + Hormone therapy | 102 (3.6) |

| Thyroid hormone treatment | 319 (11.2) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 71 (2.5) |

| Pharmacological treatment | |

| Metformin | 886 (31.1) |

| Sulfonylurea | 810 (28.4) |

| Other glucose lowering drug | 51 (1.8) |

| No glucose lowering drug | 1101 (38.7) |

| Statin | 1241 (43.6) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARB | 1957 (68.7) |

| Beta-blockers | 1366 (48.0) |

| Thiazide diuretics | 691 (24.3) |

| Aspirin | 1597 (56.1) |

| Other antiplatelet drugs | 265 (9.3) |

| Laboratory findings at baseline | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 74.5 (22.6) |

| Body weight (kg) | 77.9 (16.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.1 (6.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 148.4 (22.7) |

| HbA1c (DCCT %; mmol/mol) | 6.6 (1.0); 49 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2 (1.2) |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.3 (0.3) |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.1 (1.1) |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.9 (1.1) |

| Total testosterone (ng/dL) | 122.6 (76.6) |

| Free testosterone (ng/dL) | 2.2 (1.7) |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 44.6 (24.7) |

| LH (mIU/L) | 8.4 (4.1) |

ACE/ARB: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme/Angiotensin Receptor II Blocker; BMI: Body Mass Index; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL: High Density Lipoprotein; IGT: Impaired glucose tolerance; IFG: Impaired fasting glucose; LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein; LH: Luteinizing hormone; SHBG: Sex hormone-binding globulin.

To convert testosterone from ng/dL to nmol/L, multiply by 0.0347.

The mean (SD) of total and free testosterone levels were 122.6 (76.6) ng/dL and 2.2 (1.7) ng/dL respectively. The mean (SD) SHBG levels were 44.6 (24.7) nmol/L. There was no difference in testosterone or SHBG levels between those with or without previously established CVD (data not shown).

Testosterone, SHBG and prognosis

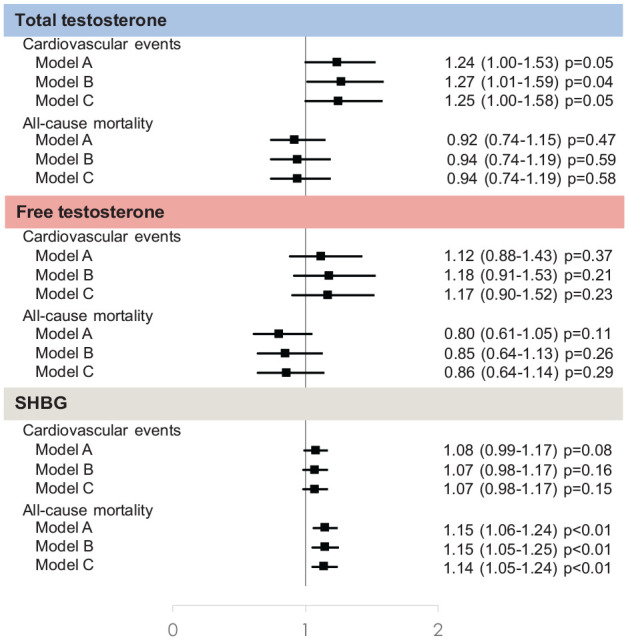

There were 377 cardiovascular events and 389 all-cause deaths during a median follow-up of 6.1 years (IQR: 5.8–6.6) in the female subgroup. The concentration of total testosterone was not significantly associated with cardiovascular events after adjustment for age (Model A) (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.00–1.53; p = 0.05) and after adjustment for 16 other cardiovascular risk factors (Model C) (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.00–1.58; p = 0.05; Figure 1). There was a nominally significant association with cardiovascular events after adjustment for 10 cardiovascular risk factors (Model B) (HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.01–1.59; p = 0.04). There was no evidence of a relationship between total testosterone levels and all-cause mortality.

Figure 1.

Hazard ratio (95% CI) for the association between sex hormones and cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality by increase of one standard deviation.

Model A adjusted for age.

Model B adjusted for age, luteinizing hormone (log and standardized), previous cardiovascular disease, previous diabetes diagnosis, use of metformin, use of statins, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, body mass index and smoking.

Model C adjusted for Model B plus menopause and no hormone therapy, menopause and hormone therapy, thyroid hormone treatment, alcohol consumption, white ethnicity, obstructive sleep apnea.

The concentration of free testosterone was not significantly associated with either cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality (Figure 1).

The concentration of SHBG was not significantly associated with cardiovascular events (Figure 1). However each SD increase was related to a 1.15 times higher hazard of all-cause mortality in the age adjusted model (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.06–1.24; p < 0.01), after further adjustment (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.05–1.25; p < 0.01) and after maximal adjustment (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.05–1.24; p < 0.01).

There were no significant interactions between hormone levels and study allocations or previously established CVD (Supplemental Table S1).

Discussion

The analysis of 2848 middle-aged and elderly women in which the majority had reached menopause and with dysglycemia and high cardiovascular risk identified baseline high SHBG as a predictor for future death during a median follow up of 6.1 years.

The current literature on the prognostic capacity of testosterone and SHBG in women is inconclusive, with some studies suggesting a U-shaped relationship with the implication that those with the lowest or the highest levels have an impaired survival15,16 while other investigations are devoid of any prognostic association.17–20 The main results from a recent report from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA; n = 2834 postmenopausal women) showed that higher total testosterone was associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. A similar trend, however with nominal significance, was seen in the present study. Interestingly, higher SHBG but not testosterone was associated with all-cause mortality. The prognostic effect of SHBG is in part supported by other studies6,16,21 and in a subgroup analysis from the MESA report excluding women on hormone therapy (n = 1934), high levels of SHBG and low levels of free testosterone and estradiol were related to an elevated risk of coronary heart disease.9 The present lack of an association between the hormones and cardiovascular disease may relate to the discrepant study populations. The MESA study recruited women free from cardiovascular disease whereas the present study included dysglycemic women either at high cardiovascular risk or with previous cardiovascular events. It may be that in patients already afflicted with glucose perturbations and cardiovascular disease there are more important factors than sex hormones to predict future cardiovascular events, as has been shown before.7,22

A possible explanation for the association between SHBG and all-cause mortality relates to the biological interplay between these hormones. SHBG binds most of circulating sex hormones such as testosterone and estradiol leaving only a small portion circulating freely and affecting tissues.23 Thus, high levels of SHBG may result in lower levels of free, bioactive sex hormones. This suggest that SHBG may be seen as a marker of bioavailable testosterone, which may be a partial explanation to its link to all-cause mortality in this group of dysglycemic women. However, the lack of a distinct predictive ability of testosterone in the present study suggests that other, testosterone independent pathways should also be considered. SHBG levels are altered in conditions such as diabetes,23 in part due to high insulin levels inhibiting SHBG production.24 During the process of progression from dysglycemia to diabetes, high insulin levels are usually found early and fall with time. This may lead to higher levels of SHBG. Thus, one hypothesis is that a rise in SHBG may reflect a fall in insulin secretion and progression of dysglycemia, which might explain its prognostic implications. To what extent the possible link between SHBG and insulin can explain the prognostic ability of SHBG cannot be derived from the present data, but underlines the need for clarifying the mechanism of action for SHBG as a predictor of mortality in dysglycemic women.

Strengths and weaknesses

The present study is based on a large, well-defined population with detailed information on menopausal status and hormone therapy. Patients were followed for a long period of time and all events were prospectively collected. Still there are some potential limitations to be considered. Testosterone was estimated by use of the LUMINEX 100/200 platforms with measurement of several biomarkers at the same time, rather than mass spectrometry, which is considered the most sensitive method. Free testosterone was not measured directly but, in line with current guidelines,25 calculated using the well established algorithm of Vermeulen et al. Moreover, although the prevalence of PCOS is likely to be low, information on this was not gathered and could have contributed to higher mean testosterone levels in the present compared to previous studies. Lastly, the observations were based on a single sample of sex hormone levels obtained at baseline.

Conclusion

In conclusion, high SHBG in middle-aged and elderly women with different levels of dysglycemia and at high cardiovascular risk is related to an increased risk of all-cause mortality and high total testosterone was nominally associated with cardiovascular events. This highlights the importance of further studies regarding the prognostic role of androgens in females.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-dvr-10.1177_14791641211002475 for Testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin in dysglycemic women at high cardiovascular risk: A report from the Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention trial by Anne Wang, Hertzel C Gerstein, Shun Fu Lee, Sibylle Hess, Guillaume Paré, Lars Rydén and Linda G Mellbin in Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: AW, HG, LR and LM contributed to the concept and design of the study. SH suggested testosterone, SHBG and LH to be measured in the biomarker panel for ORIGIN. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. SL performed the statistical analyses. AW drafted the report together with HG, LR and LM and all authors critically revised it. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability: The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available but will be disclosed upon request and approval of the proposed use of the data by a review committee.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AW has nothing to declare. HG holds the McMaster-Sanofi Population Health Institute Chair in Diabetes Research and Care. He has received research grant support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Abbott, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi and honoraria for speaking and/or consulting from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Abbott, Eli Lilly, Merck, Janssen and Kowa Research Institute. SL has nothing to declare. SH is an employee and shareholder of Sanofi. GP reports grants from Sanofi. LR reports grants from The European Society of Cardiology, Amgen, Bayer AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Merck, Family E Perssons Foundation and honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Merck, Bayer AG and Novo Nordisk. LM reports grants from Bayer AG and honoraria from Bayer AG, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Sanofi, Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation and the Stockholm County Council.

ORCID iD: Anne Wang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4047-7730

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4047-7730

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Crandall CJ, Barrett-Connor E.Endogenous sex steroid levels and cardiovascular disease in relation to the menopause: a systematic review. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2013; 42: 227–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spoletini I, Vitale C, Pelliccia F, et al. Androgens and cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women: a systematic review. Climacteric 2014; 17: 625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis SR.Testosterone: action, deficiency, substitution. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan CL, Jenkins-Jones S, Currie CJ, et al. Evaluation of adverse outcome in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome versus matched, reference controls: a retrospective, observational study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: 3251–3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wild S, Pierpoint T, Jacobs H, et al. Long-term consequences of polycystic ovary syndrome: results of a 31 year follow-up study. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2000; 3: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis SR, Wahlin-Jacobsen S.Testosterone in women—the clinical significance. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3: 980–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wehr E, Pilz S, Boehm BO, et al. Low free testosterone levels are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in postmenopausal diabetic women. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 1771–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding EL, Song Y, Manson JE, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1152–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao D, Guallar E, Ouyang P, et al. Endogenous sex hormones and incident cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 2555–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel SM, Ratcliffe SJ, Reilly MP, et al. Higher serum testosterone concentration in older women is associated with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 4776–4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Origin Trial Investigators, Gerstein HC, Bosch J, et al. Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Origin Trial Investigators, Gerstein H, Yusuf S, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics for a large international trial of cardiovascular disease prevention in people with dysglycemia: the ORIGIN Trial (Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention). Am Heart J 2008; 155: 26–32, 32 e21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerstein HC, Pare G, McQueen MJ, et al. Identifying novel biomarkers for cardiovascular events or death in people with dysglycemia. Circulation 2015; 132: 2297–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM.A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84: 3666–3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laughlin GA, Goodell V, Barrett-Connor E.Extremes of endogenous testosterone are associated with increased risk of incident coronary events in older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 740–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armeni E, Lambrinoudaki I.Androgens and cardiovascular disease in women and men. Maturitas 2017; 104: 54–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaffrath G, Kische H, Gross S, et al. Association of sex hormones with incident 10-year cardiovascular disease and mortality in women. Maturitas 2015; 82: 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Arslan AA, et al. Endogenous hormones and coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Atherosclerosis 2011; 216: 414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meun C, Franco OH, Dhana K, et al. High androgens in postmenopausal women and the risk for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease: the Rotterdam study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018; 103: 1622–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeller T, Appelbaum S, Kuulasmaa K, et al. Predictive value of low testosterone concentrations regarding coronary heart disease and mortality in men and women - evidence from the FINRISK97 study. J Intern Med 2019; 286: 317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sievers C, Klotsche J, Pieper L, et al. Low testosterone levels predict all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in women: a prospective cohort study in German primary care patients. Eur J Endocrinol 2010; 163: 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haffner SM, Moss SE, Klein BE, et al. Sex hormones and DHEA-SO4 in relation to ischemic heart disease mortality in diabetic subjects. The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care 1996; 19: 1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldman AL, Bhasin S, Wu FCW, et al. A reappraisal of testosterone’s binding in circulation: physiological and clinical implications. Endocr Rev 2017; 38: 302–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Nieschlag S.Testosterone: action, deficiency, substitution. 4th ed.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp.xi, 569. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wierman ME, Arlt W, Basson R, et al. Androgen therapy in women: a reappraisal: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99: 3489–3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-dvr-10.1177_14791641211002475 for Testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin in dysglycemic women at high cardiovascular risk: A report from the Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention trial by Anne Wang, Hertzel C Gerstein, Shun Fu Lee, Sibylle Hess, Guillaume Paré, Lars Rydén and Linda G Mellbin in Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research