Abstract

We used pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to study the epidemiology and population structure of Haemophilus influenzae type b. DNAs from 187 isolates recovered between 1985 and 1993 from Aboriginal children (n = 76), non-Aboriginal children (n = 106), and non-Aboriginal adults (n = 5) in urban and rural regions across Australia were digested with the SmaI restriction endonuclease. Patterns of 13 to 17 well-resolved fragments (size range, ∼8 to 500 kb) defining 67 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) types were found. Two types predominated. One type (n = 37) accounted for 35 (46%) of the isolates from Aboriginals and 2 (2%) of the isolates from non-Aboriginals, and the other type (n = 41) accounted for 2 (3%) of the isolates from Aboriginals and 39 (35%) of the isolates from non-Aboriginals. Clustering revealed seven groups at a genetic distance of ∼50% similarity in a tree-like dendrogram. They included two highly divergent groups representing 50 (66%) isolates from Aboriginals and 6 (5%) isolates from non-Aboriginals and another genetically distinct group representing 7 (9%) isolates from Aboriginals and 81 (73%) isolates from non-Aboriginals. The results showed a heterogeneous clonal population structure, with the isolates of two types accounting for 42% of the sample. There was no association between RFLP type and the diagnosis of meningitis or epiglottitis, age, sex, date of collection, or geographic location, but there was a strong association between the origin of isolates from Aboriginal children and RFLP type F2a and the origin of isolates from non-Aboriginal children and RFLP type A8b. The methodology discriminated well among the isolates (D = 0.91) and will be useful for the monitoring of postvaccine isolates of H. influenzae type b.

Before the introduction of conjugate vaccines in 1992, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease was a major cause of morbidity and mortality in Australian children, particularly among Aboriginal populations, in whom the incidence of Hib disease was among the highest in the world. Overall, 600 to 700 cases of invasive Hib disease occurred each year in Australia. While the incidence of Hib disease has dropped dramatically since vaccination policies have been in place, invasive disease due to Hib still occurs. Between July 1993 and June 1996, 412 cases of invasive disease due to Hib, including 18 deaths, were reported to the Hib Case Surveillance Scheme. Thirty-four cases met the Australian case definition of a vaccine failure. However, a further 24 cases would meet the United Kingdom vaccine failure definition that includes cases occurring after the administration of just two rather than three doses of vaccine when the first dose is given before the age of 7 months (14).

Studies on the epidemiology of Hib disease in Australia have demonstrated significant differences in the incidence of epiglottitis and meningitis between urban areas (7, 12, 20, 21), an extremely high incidence of invasive Hib disease among Aboriginal children compared to that among non-Aboriginal children (9, 10, 11), and a lack of epiglottitis among Aboriginals (9). The reasons for the unique epidemiology of Hib disease remain largely unknown, and there is little information about its population structure and genetic diversity in Australia. The purpose of this study was to characterize isolates of Hib, determine whether restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) types correlated with the epidemiology of disease, and assess the usefulness of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) as the basis of a database of genetic types to monitor Hib isolates in the postvaccine era.

We used contour-clamped homogeneous electric field PFGE (CHEF PFGE) to investigate the genetic diversity and population structure of Hib and to develop a database of genetic types to use in the surveillance of Hib. CHEF PFGE is now a well-established methodology in many pathology laboratories and is most often used to analyze relatively small sets of isolates related to outbreaks of disease. It has been used to construct a physical map of Hib strain Eagan and to characterize 10 genetically heterogeneous Hib isolates previously typed by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (4). It has also been used to study insertion mutations in the transferrin binding system of Hib (5), and other types of PFGE have been used to estimate its genome size (17). Results of PFGE for 29 epidemiologically unrelated Hib isolates demonstrated evolutionary divergence consistent with that of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (1). PFGE, however, has not been applied previously to the study of a large number of clinical isolates of Hib in population genetic studies. In conjunction with mathematical analysis we used the RFLPs generated by PFGE to provide numerical estimates of genetic diversity among 187 isolates to construct a dendrogram and to assess the correlation of genetic types with the epidemiology of Hib.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

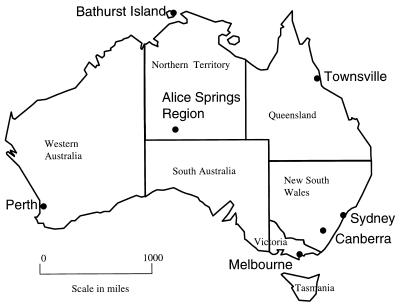

One hundred eighty-eight previously characterized Hib isolates from collections representing urban and rural regions across Australia were examined. All were recovered between 1985 and 1993. Thirty-four isolates from Canberra and 37 isolates from Sydney were obtained from the Canberra Hospital, Australian Capital Territory; 20 isolates from Melbourne and 10 isolates from the Alice Springs region were obtained from the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, Victoria; 20 isolates from metropolitan Perth and rural areas of Western Australia were obtained from the Princess Margaret Hospital in Perth, Western Australia; 46 isolates from the Alice Springs Region were obtained from the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Brisbane, Queensland; 19 isolates from Bathurst Island were obtained from the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin, Northern Territory; and 2 isolates were obtained from the Townsville General Hospital, Queensland. The geographic origins of the isolates are depicted in Fig. 1. The sample comprised 83 isolates recovered from the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningitis, 29 isolates from the blood of patients with epiglottitis, and 39 isolates from patients with other diagnoses including 13 isolates from the blood of patients for whom no clinical information was available. Twenty-four isolates were from healthy carriers. All the isolates were genotyped to confirm that they were type b. One was found to be nonencapsulated and was excluded from the study. A breakdown of the Hib sample (n = 187) distribution by geographic location, origin from an Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal, and disease association is shown in Table 1. An isolate of Hib, HS0008, obtained from the Canberra Hospital collection was used as a size standard. All isolates except 20 isolates which had been lyophilized were stored at −70°C.

FIG. 1.

Geographical map of Australia showing the locations from which isolates were obtained. The distance both between Perth and Sydney and between Bathurst Island and Melbourne is approximately 2,500 miles (4,000 km).

TABLE 1.

Geographic location and disease association of 187 Hib isolates recovered from Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals

| Group and geographic location | No. of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meningitis | Epiglottitis | Other | Carrier | Total | |

| Aboriginal | 23 | 0 | 29 | 24 | 76 |

| Alice Springs region, Northern Territory | 11 | 0 | 28a | 6 | 45 |

| Bathurst Island, Northern Territory | 0 | 0 | 1b | 18 | 19 |

| Perth, Western Australia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Rural Western Australia | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Non-Aboriginal | 60 | 29 | 22 | 0 | 111 |

| Canberra, Australian Capital Territory | 20 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| Melbourne, Victoria | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Sydney, New South Wales | 21 | 1 | 15c | 0 | 37 |

| Perth, Western Australia | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Townsville, Queensland | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Alice Springs region, Northern Territory | 3 | 0 | 7d | 0 | 10 |

| Total | 83 | 29 | 51 | 24 | 187 |

The isolates were associated with pneumonia (n = 9), gastroenteritis (n = 9), acute lower respiratory tract infection (n = 4), cellulitis (n = 1), febrile disease (n = 1), FTT (n = 1), conjunctivitis (n = 1), bronchiolitis (n = 1), and otitis media (n = 1).

The isolate may be associated with otitis media.

Thirteen invasive isolates recovered from blood (diagnosis unknown) and 2 isolates associated with cellulitis.

Invasive isolates recovered from blood (diagnosis unknown).

DNA preparation.

The preparation of chromosomal DNA was performed by a modification of the method described by Bautsch (3). DNA was prepared in a 1:1 ratio in an intact 1% agarose (SeaPlaque low-gelling-temperature agarose; FMC Bioproducts) matrix with cells harvested from an overnight growth on chocolate agar suspended in solution 21 (19) to an optical density of 1.8 at 650 nm. The DNA-agarose plugs (1 by 8 by 19 mm) were lysed in a solution of proteinase K (1 mg/ml) in 0.5 M EDTA–1% sodium lauryl sarcosine and were incubated overnight at 50°C. The plugs were rinsed for 2 h in TE (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and were then stored in fresh TE at 4°C.

Restriction endonuclease digestion.

H. influenzae has a base composition of 37 mol% G+C. Therefore, enzymes recognizing 6-bp sequences comprising only G−C bases should produce a small number of distinct fragments. Initially, SmaI (CCC↓↑GGG) and ApaI (G↑GGCC↓C) were used. Washing of plugs and digestion of the DNA with endonucleases were performed as described by Inglis et al. (16). SmaI (Boehringer Mannheim) and ApaI (Boehringer Mannheim) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each analysis, one-half of a DNA-agarose plug was digested overnight with 30 U of enzyme at 30°C (SmaI) or 37°C (ApaI).

PFGE analysis.

Separation of DNA fragments with a clamped homogeneous electric field device (CHEF DRII; Bio-Rad) at 200 V was carried out in 1% agarose (type II-A; Medium EEO; Sigma) gels made with 0.5× TBE buffer (0.045 M Tris-borate, 0.001 M EDTA) in 0.5× TBE buffer at 12 to 14°C. Pulse parameters for both SmaI and ApaI digests included a ramp of pulses for 6 to 8 s for 7 h followed by a ramp of 1 to 38 s for 17 h. The gels were stained for 30 min with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) in distilled water and were then destained in distilled water for 1 h or more and photographed (Polaroid 667) with a UV light source. DNA size standards were lambda phage concatemers, a lambda phage HindIII digest, and the genomic fragments from Hib HS0008. Most strains were independently digested up to three times.

Estimation of genetic diversity between isolates and construction of dendrograms.

The numbers and mobilities of the fragments were determined by visual examination of the Polaroid photographs of the stained gels. When comparison of the sizes of the fragments from isolates from different gels was questionable, another gel was run so that the fragments could be compared while they were in close proximity. Numerical analysis of RFLP patterns was performed by identifying the proportion of fragments shared by pairs of isolates by the method of Nei and Li (24) (also known as the Dice coefficient or coefficient of similarity) and calculated as F = 2nxy/(nx + ny), where nx is the total number of DNA fragments from isolate x, ny is the total number of fragments from isolate y, and nxy is the number of fragments identical in the two isolates.

A matrix of F values for all pairs of isolates was constructed, and a dendrogram was constructed by the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (26) with the TDRAW program. The programs used for mathematical calculations and construction of the dendrogram are accessible in the package RAPDistance Programs, distributed by J. Armstrong et al., Research School of Biological Sciences, Australian National University (2).

Southern blotting and hybridization.

Capsular type was confirmed by hybridization of Southern blots with 32P-labelled pU082, a cloned fragment which spans type b-specific parts of the H. influenzae cap locus (18). Hybridization products were detected by autoradiography. If no signal was detected, isolates were reprobed with pU038, which spans serotype-specific and non-serotype-specific parts of the cap locus (18). Isolates which did not hybridize with pU082 were not included in the study. The probes were kindly provided by E. Richard Moxon.

The DNA fragments separated by PFGE were acid depurinated in 0.25 M HCl two times for 8 min each time followed by two 8-min rinses in 0.4 M NaOH and were then transferred onto Hybond-N nylon membranes (Amersham) in 10 mM NaOH overnight. The membranes were prehybridized overnight at 70°C in a buffer containing 2× PE (1× PE is 0.133 M sodium phosphate plus 1 mM EDTA), 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 1% bovine serum albumin. The probe consisted of 25 ng of pU082 or pU038 DNA labelled with [α-32P]dCTP with the Megaprime labelling system (Amersham). The probe was incubated overnight with the membranes at 70°C in the same hybridization buffer. The membranes were then washed three times for 15 min each time in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS at room temperature and once in 5× SSC–1% SDS at 70°C and were analyzed by autoradiography.

RESULTS

Selection of isolates for examination.

All of the isolates (n = 188) obtained for this study had previously been identified by conventional methods including serotyping. One failed to hybridize with either pU038 or pU082 and was excluded from the study, leaving 187 isolates for analysis.

Analysis of RFLPs.

SmaI was used for the main analysis of RFLPs because the number and size of fragments produced with SmaI were fewer and more distinct than those produced with ApaI. Comparison of the similarity matrices produced with each enzyme with a subset of the sample by the program DIPLOMO (29) yielded a correlation coefficient of 0.90, and the grouping of the isolates into major divisions established with SmaI was confirmed with ApaI.

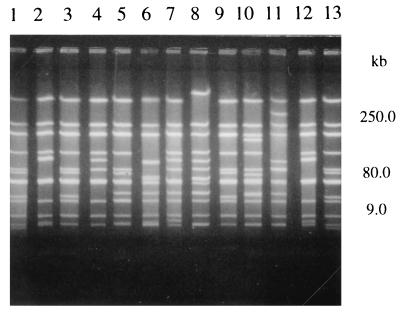

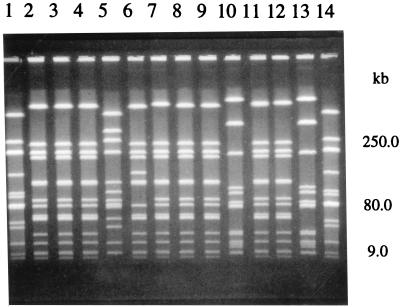

Well-resolved patterns of 13 to 17 SmaI fragments of approximately 8 to 500 kb representing 67 RFLP types were found among the 187 isolates. Figures 2 and 3 show representative results of the SmaI digests. A total of 78 distinct fragments were observed on the gels. Only one of these fragments was present in all the RFLP patterns, and it did not carry the cap locus detected in the hybridization studies. Forty-eight (72%) of the RFLP types had single isolates, and 19 (28%) types had multiple isolates. The isolates of the two types with the most numbers of isolates, types F2a (n = 37) and A8b (n = 41), represented 42% of the sample. The remaining 17 types with multiple members had two to eight isolates each.

FIG. 2.

SmaI-generated fragments obtained by CHEF PFGE of genomic DNAs of Hib isolates obtained from non-Aboriginals. A fragment size scale is shown on the right. Lanes 1 and 13, fragment standards from Hib HS0008; lane 2, RFLP type A6a; lane 3, RFLP type A1a; lane 4, RFLP type A8b; lane 5, RFLP type A3a; lane 6, RFLP type E1; lane 7, RFLP type A9a; lane 8, RFLP type E3; lane 9, RFLP type A1b; lane 10, RFLP type B6; lane 11, RFLP type C1a; lane 12, RFLP type A6b. The photograph seen here was prepared from a Polaroid picture. The original Polaroid picture does not have the very white background seen in the lanes here. The background is relatively faint in the original Polaroid, and a more faithful copy can be prepared.

FIG. 3.

SmaI-generated fragments obtained by CHEF PFGE of genomic DNA of Hib isolates obtained from Aboriginals. A fragment size scale is shown on the right. Lanes 1 and 14, fragment standards from Hib HS0008; lanes 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 11, and 12, RFLP type F2a; lane 5, RFLP type D1a; lane 6, RFLP type F2d; lane 7, RFLP type F2b; lanes 10 and 13, RFLP type G1. The photograph seen here was prepared from a Polaroid picture. The original Polaroid picture does not have the very white background seen in the lanes here. The background is relatively faint in the original Polaroid, and a more faithful copy can be prepared.

Nineteen types were found among the isolates from Aboriginal children (n = 76), and 53 types were found among those from non-Aboriginal children and adults (n = 111). The ratio of isolates to type was 4:1 and 2.1:1 among the Aboriginal and the non-Aboriginal populations, respectively, with only five types shared by both population groups. For the most part, within each of the five shared types, the isolates from Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals were from the same geographic region.

Two types predominated. Type F2a accounted for 35 (46%) of the isolates from Aboriginals but only 2 (2%) of the isolates from non-Aboriginals (Table 2). Type A8b accounted for 39 (35%) of the isolates from non-Aboriginals and 2 (3%) of the isolates from Aboriginals (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Hib RFLP type F2a (n = 37), which accounted for 46% of the Aboriginal isolates

| Geographic location | No. of isolates

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meningitis

|

Epiglottitis

|

Other

|

Carrier

|

Total

|

||||||

| Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | |

| Canberra | ||||||||||

| Melbourne | ||||||||||

| Sydney | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Perth | 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| Townsville | ||||||||||

| Alice Springs region | 1 | 4 | 14a | 4 | 1 | 22 | ||||

| Bathurst Island | 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| Rural Western Australia | 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| Total | 1 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 35 |

The isolates were associated with pneumonia (n = 5), acute lower respiratory tract infection (n = 3), gastrointestinal disorders (n = 3), cellulitis (n = 1), bronchiolitis (n = 1), and FTT (n = 1).

TABLE 3.

Distribution of Hib RFLP type A8b (n = 41), which accounted for 35% of the non-Aboriginal isolates

| Geographic location | No. of isolates

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meningitis

|

Epiglottitis

|

Other

|

Carrier

|

Total

|

||||||

| Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Aboriginal | |

| Canberra | 5 | 1 | 6 | |||||||

| Melbourne | 4 | 7 | 11 | |||||||

| Sydney | 11 | 6a | 17 | |||||||

| Perth | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Townsville | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Alice Springs region | 1 | 2a | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Bathurst Island | ||||||||||

| Rural Western Australia | ||||||||||

| Total | 22 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 2 |

Invasive isolates (diagnosis unknown).

The number of fragments shared between pairs ranged from all fragments (these pairs were considered to be identical) to 2 of 29 fragments for the most diverse pairs. The RFLP patterns were stable. When the isolates were repeatedly subcultured, their DNAs yielded unchanged SmaI fragment patterns.

Genetic relationships determined by numerical analysis of fragment length polymorphisms.

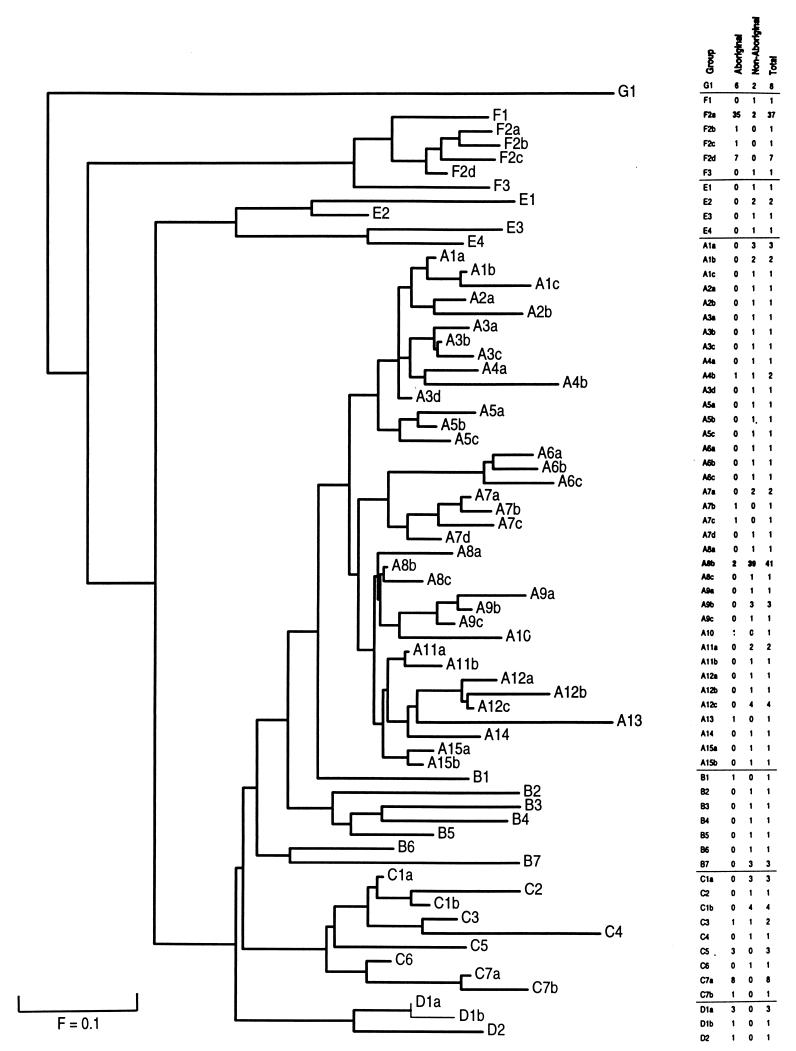

F values ranged from 0.07 to 1, and these correspond to a similarity range of from 7 to 100%. An F value of 1, determined when all fragments between a pair were shared, corresponded to identical fragment patterns on the gels. Thus, when F was equal to 1, the members of the pair are considered to be the same RFLP type. The smallest F value found, 0.07, corresponded to pairs for which only 2 of the 14 and 15 fragments of the isolate pair were shared. A similarity matrix based on pairwise comparison of the F values for all RFLP types was used to calculate a dendrogram (Fig. 4), as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram showing the clustering of 67 SmaI RFLP types of 187 Hib isolates obtained from Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals from rural and urban regions around Australia. The dendrogram was generated with the mathematical model of Nei and Li (24), and distances were calculated by the neighbor-joining method. The distance between any two taxa is the sum of the horizontal lines between them. The bar indicates an F value of 0.1, or 10% similarity. Seven major groups cluster at an F value of ≤0.5, and 39 branches representing 39 clonal groups cluster at an F value of ≥0.9. Only types G1, F2a, A4b, A8b, and C3 share members from both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

The isolates fell into seven major clusters, designated groups A to G, at an F value of ≤0.5, i.e., at a genetic distance representing less than 50% similarity. There were 39 branches at an F value of ≥0.9, corresponding to a genetic distance of greater than 90% similarity, and these branches are referred to as clonal groups. Each of the clonal groups was represented by a single type or a cluster of closely related types whose members differed by three or fewer fragments. For comparative purposes, each RFLP type was given a three-character designation according to the major cluster (A, B, C, D, E, F, or G) in which it fell, the clonal group of which it was a member in that cluster (numbered from 1), and its unique type in the clonal group (lettered from a).

Two highly divergent groups (designated F and G) comprising seven types represented 50 (66%) of the isolates from Aboriginals and 6 (5%) of the isolates from non-Aboriginals. A single genetically distinct group (designated A) comprising 37 types represented 7 (9%) of the isolates from Aboriginals and 81 (72%) of the isolates from non-Aboriginals.

The largest major cluster, group A, included 88 isolates and comprised 37 types in 15 clonal groups, 13 of which comprised multiple types. Type A8b, which comprised 22% of the sample, and 35% of the isolates from non-Aboriginals, fell in group A. The distribution of RFLP types among groups B to E is shown in Fig. 4. Group F had 48 members among six types in four clonal groups including type F2a, which comprised 20% of the sample and 46% of the isolates from Aboriginals. Group G included a single type, type G1, which comprised six isolates from Aboriginals isolates and two isolates from non-Aboriginals from the Alice Springs region. Type G1 was the most highly divergent type in the sample, with less than 15% similarity to either of the two predominant types, types F2a and A8b (F = 0.13 and 0.14, respectively).

The largest genetic distance estimate was between two members of group A (types A2b and A10) and the members of group G. They were separated by genetic distances with F values of 0.07, with only 2 of 29 fragments shared between pairs.

Genetic diversity and correlation to epidemiology.

Clustering of RFLP types was not associated with disease type. Isolates from patients with meningitis and epiglottitis, as expected, were each represented by a diverse range of types, and no single type was associated with a particular diagnosis or carriage. In addition, no association was found between age, sex, date of collection, or geographic location. A strong association, however, between both the origin of isolates from Aboriginal children and RFLP type F2a and the origin of isolates from non-Aboriginal children and RFLP type A8b (P < 0.001 by chi-square analysis) was found and three other RFLP types (types F2d, G1, and C7a) with multiple members were composed of predominantly isolates from Aboriginals.

Type F2d comprised seven isolates and fell in the same clonal group as type F2a. It accounted for six isolates from Aboriginal children living in the Alice Springs region and two isolates from Aboriginal children living in rural Western Australia. Type G1 included six isolates from Aboriginals and two isolates from non-Aboriginals from the Alice Springs region. Eight isolates from Aboriginal children shared RFLP type C7a, which fell in a group that comprised 13 isolates from Aboriginals and 11 isolates from non-Aboriginals. The association of type C7a with origin in an Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal or geographic location is not statistically significant; however, seven of the eight isolates of type C7a were from Bathurst Island in the Northern Territory, as was the single member in a clonally related type, type C7b.

DISCUSSION

Our aim was to ascertain whether CHEF PFGE could be useful in distinguishing between isolates of Hib recovered in Australia before the introduction of vaccines and to investigate their genetic diversity. It has been shown that the Hib population structure is clonal (23), which implies that the number of different types will be limited. One practical implication of this is that general, nonspecific procedures such as RFLP analysis can be used to identify bacteria in such populations (25).

In the analysis of the Hib isolates described here, RFLPs were determined for fragments from the entire genome except for fragments that were present in such small amounts that they did not bind sufficient ethidium bromide to be visible or that were so small (<6 kb) that they ran off the end of the gel during electrophoresis; such fragments would account for a small proportion of the genome.

The sample of 187 Hib isolates that we analyzed comprised 67 different types of SmaI RFLP patterns with 17 or fewer fragments that were well resolved by PFGE. Closely related and more distantly related genomic types were easily discriminated. When Simpson’s index of diversity (15) was applied to the system an index of D equal to 0.91 was calculated. The SmaI RFLPs fell into seven major clusters in a tree-like dendrogram that is consistent with a clonal population structure, as is the presence of two predominant types among the 67 types that were found. The two predominant types, referred to as types F2a and A8b, accounted for 42% of the sample and included almost one-half of the isolates from Aboriginals and over one-third of the isolates from non-Aboriginals, respectively. Not surprisingly, the results described a heterogeneous clonal population structure and extend the geographic range over which the clonality of Hib has been demonstrated.

Differences and similarities between Hib isolates were readily visualized from the CHEF patterns, and a general grouping of the isolates could be established in this way. However, a more quantitative approach can be derived by subjecting the data to the analytical procedures described by Nei and Li (24). In an attempt to describe what are otherwise qualitative differences in fragment patterns among a large body of comparative data, we estimated DNA similarities on the basis of the fraction of common fragments generated by the endonuclease. The value generated is referred to as the F value.

It has been suggested by Tenover et al. (27) that, in the context of analyzing outbreak strains with one endonuclease, a one- to three-fragment difference can occur between closely related strains and possibly related strains can be found among those that differ by four to six fragments. It has also been reported that closely related strains of Enterococcus faecalis can differ by up to six bands and that patterns have been shown to differ by up to seven bands and still be clonally related (28). Furthermore, using hybridization analysis and PFGE in the investigation of insertion mutations in the transferrin binding systems of Hib, Curran et al. (5) found five different changes of zero to three bands between the SmaI fragments of five insertion mutants. These results remind us that several different chromosomal mutations could generate the same phenotype.

Thus, the values of F obtained should not be seen as precise estimates of genetic distance but should be seen as summary values indicative of overall similarities and differences between isolates and a means of illustrating relationships within a large body of comparative data. F values of ≥0.9 representing pairs of isolates that differ by up to three fragments were used to determine closely related isolates in this study, and we describe such closely related isolates as a clonal group. However, pairs of isolates that are closely related can be found as members of different clonal groups as well as within clonal groups, so the number of branches is not an absolute representation of all closely related pairs. For example, the predominant RFLP type, type A8b, is found within a clonal group that comprises two other closely related types. It is also closely related (F ≥ 0.9) to 16 types found in 10 other clonal groups within group A.

No association between RFLP type and age, sex, date of collection, or disease manifestation was found. Because of the lack of isolates from Aboriginals from urban areas and isolates from non-Aboriginals from rural areas, the association between geographic location and type was not found to be significant in this sample. The genetic distance separating the important major lineages ranged from a similarity of 20% to one of 50%, yet there is apparently an equivalent ability to cause disease among the lineages. One of the patterns of Hib disease in Australia was a significant difference in the incidence of epiglottitis among urban populations. The incidence of epiglottitis in Victoria (7) and the Australian Capital Territory (20) was twice that in Sydney (21) and Western Australia (12). Another pattern of Hib disease in Australia was the lack of epiglottitis among Aboriginal children, similar to the epidemiology of Hib disease among other high-risk indigenous populations (9). The possibility that differences in the incidence of epiglottitis among different population groups are related to differences in the strains of Hib has not been demonstrated in this study, and the patterns of the incidence of epiglottitis in Australia remain unexplained. Other restriction enzymes which sample different areas of the genome may detect molecular differences that demonstrate clonal disease specificity, but we did not detect such a relationship among the SmaI-generated RFLP types in this sample.

Analysis of isolates from Aboriginal children living in geographically isolated regions of Australia revealed a relatively small number of genetically distinct RFLP types. A strong association was found between the origin of isolates from Aboriginal children and one of these types. Isolates from non-Aboriginal populations were more diverse and genetically distinct from most isolates from Aboriginal populations, and one of these types, found in a cluster of closely related isolates, was strongly associated with the origin of isolates from non-Aboriginal children. The data support the hypothesis described by Musser et al. (22) that a causal relationship exists between the degree of ethnic mixing of human populations and the degree of diversity in the clonal composition of Hib populations. According to this hypothesis, a large component of the current geographic variation in the clonal composition of Hib reflects an older pattern of differentiation that evolved in relative geographic isolation before the Age of Exploration (beginning about 450 years ago) and has not been completely obscured by recent demographic changes (22). It explicitly predicts that isolates from Aboriginal populations largely belong to a distinctive set of clones, as described in this study.

If Hib had been present in Aboriginal populations before the settlement of Australia by Europeans, the striking difference between the predominant Aboriginal type and the predominant non-Aboriginal type suggests a separate evolution of strains. The time span since permanent settlement by Europeans that began on the east coast of Australia in 1788 does not support a long history of differentiation that may be needed for such a deep divergence between types. Therefore, it is more likely that urban non-Aboriginal types have recently been introduced from other areas of the world rather than derived from the Aboriginal types. Nonetheless, more extensive analysis is needed to provide data to support the explanation of the phylogenetic relationship between the Hib types described here.

Prior to the introduction of vaccination, the incidence of Hib disease in Aboriginal populations was reported to be extremely high and varied among communities. The estimated annual incidence among Aboriginal children under age 5 in central Australia (an area corresponding to the Alice Springs region in this study) was 991 cases per 100,000, with a high proportion of cases of meningitis and a fatality rate of 8.3% (8). The corresponding rate among non-Aboriginal children in central Australia was 215 per 100,000, which was significantly higher than that in other areas of the Northern Territory and four times higher than that in Melbourne (9). It was concluded that environmental factors and cultural factors were responsible for the very high incidence of Hib disease in Aboriginal communities (8). However, this does not explain the increased incidence in non-Aboriginal children. An alternative explanation, that the strains circulating among Aboriginal children and affecting some non-Aboriginal children in the same geographic area are more virulent than urban strains, has not been investigated.

Our data show that a few distinct types are responsible for Hib disease among Aboriginal populations, and the high incidence of disease in very young children indicates that the very high transmission rates are associated with environmental factors. According to Ewald’s (6) cultural vector hypothesis, increased transmission rates and repeated passage through human hosts may lead to the selection of more rapidly multiplying and virulent strains. If so, such strains of Hib in Aboriginal populations are also likely to spread to non-Aboriginal children in the same geographic area and result in an increased diversity of strains in this group as well as an increased incidence of disease.

The differences found between Hib types from Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations by PFGE demonstrate the practical discriminatory power of PFGE for the analysis of large numbers of Hib isolates. Analysis of the huge similarity matrices required for large samples has been facilitated by the availability of computer programs and, with the standardization of PFGE methods, would allow inter- and intralaboratory comparisons of results in a common database. This would improve surveillance by increasing the capacity to detect new strains of Hib and monitor populations for the presence of old strains. The usefulness of the system was shown when two isolates of Hib recently recovered in a nursing home outbreak in the Sydney region (13) were analyzed, and both were shown to have patterns identical to that of SmaI type A8b. This suggested that these isolates were not a new genotype since they were identical to the predominant type found in Sydney in the prevaccine era. We believe that this system will be useful for the monitoring of future Hib isolates from children in whom the vaccine has failed, unimmunized children, and adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Peter R. Stewart and Jan Bell for critical assistance in the early stages of this work and Adrian Gibbs for invaluable help in creating dendrograms. We also thank Michael Gratten of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Amanda Leach of the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin, Leonie Walpington of the Princess Margaret Hospital in Perth, and Chris Ashhurst-Smith of Townsville General Hospital for sending us isolates and Frances Oppedisano of the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne for sending us isolates and the pU038 and pU082 probes originally provided to G. L. Gilbert by E. Richard Moxon of the John Radcliff Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom.

The work presented here was undertaken in the Division of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the Faculty of Science at the Australian National University with funds and resources provided by that Division and the Graduate School. An Australian Postgraduate Research Award provided financial support for P. E. Moor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbeit R D, Dunn R, Maslow J, Goldstein R, Musser J M. Program and abstracts of the 30th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. Resolution of evolutionary divergence and epidemiologic relatedness among H. influenzae type b (Hib) by pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), abstr. 1144; p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong, J. S., A. J. Gibbs, R. Peakall, and G. Weiller. 1994. The RAPDistance package. [Online.] Australian National University. ftp://life.anu.edu.au/pub/software/RAPDistance or http://life.anu.edu.au/molecular/software/rapd.html. [October 1998, last date accessed.]

- 3.Bautsch W. Bacterial genome mapping by two-dimensional pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (2D-PFGE) Methods Mol Biol. 1992;12:185–201. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-229-9:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler P, Moxon E R. A physical map of the genome of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2333–2342. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curran R, Hardie K R, Towner K J. Analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of insertion mutations in the transferrin-binding system of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Med Microbiol. 1994;41:120–126. doi: 10.1099/00222615-41-2-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewald P W. Evolution of infectious disease. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert G L, Clements D A, Broughton S J. Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in Victoria, Australia 1985–1987. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:252–257. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199004000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna J. The epidemiology of invasive Haemophilus influenzae infections in children under five years of age in the Northern Territory: a three-year study. Med J Aust. 1990;152:234–240. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb120916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanna J N. The epidemiology and prevention of Haemophilus influenzae type b in Aboriginal children. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992;28:352–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanna J N. Haemophilus influenzae type b meningitis in far north Queensland, 1989 to 1994. Commun Dis Intell. 1995;19:91–93. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2004.28.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanna J N, Wild B E. Bacterial meningitis in children under five years of age in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 1991;155:160–164. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb142183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna J N, Wild B E, Sly P D. The epidemiology of acute epiglottitis in children in Western Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992;28:459–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heath T C, Hewitt M C, Jalaludin B, Roberts C, Capon A G, Jelfs P, Gilbert G L. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in elderly nursing home residents: two related cases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:179–182. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herceg A. The decline of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in Australia. Commun Dis Intell. 1997;21:173–175. doi: 10.33321/cdi.1997.21.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter P R, Gaston M A. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inglis B, El-Adhami W, Stewart P. Methicillin-sensitive and -resistant homologues of Staphylococcus aureus occur together among clinical isolates. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:323–328. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauc L. Determination of genome size of Haemophilus influenzae Sb: analysis of DNA restriction fragments. Acta Microbiol Pol. 1992;41:13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroll J, Moxon E. Capsulation and gene copy number at the cap locus of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:859–864. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.859-864.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J J, Smith H O. Sizing of the Haemophilus influenzae Rd genome by pulsed-field agarose gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4402–4405. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4402-4405.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGregor A R, Bell J M, Abdool I M, Collignon P J. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae infection in the Australian Capital Territory region. Med J Aust. 1992;156:569–572. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb121421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntyre P B, Leeder S R, Irwig L M. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b in Sydney children 1985–1987: a population-based study. Med J Aust. 1991;154:832–837. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb121377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musser J, Kroll J S, Granoff D M, Moxon E R, Brodeur B R, Campos J, Dabernat H, Frederiksen W, Hamel J, Hammond G, Hoiby E A, Jonsdottir K R, Kabeer M, Kallings I, Khan W N, Kilian M, Knowles K, Koornhof H J, Law B, Li K I, Montgomery J, Pattison P E, Piffaretti J-C, Takala A K, Thong M L, Wall R A, Ward J I, Selandar R K. Global genetic structure and molecular epidemiology of encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:75–111. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musser J M, Kroll J S, Moxon E R, Selander R K. Clonal population structure of encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1837–1845. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1837-1845.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nei M, Li W H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porras O, Caugant D A, Gray B, Lagergard T, Levin B R, Svanborg-Eden C. Difference in structure between type b and nontypable Haemophilus influenzae populations. Infect Immun. 1986;53:79–89. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.79-89.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thal L A, Silverman J, Donabedian S, Zervos M J. The effect of Tn916 insertions on contour-clamped homogeneous electrophoresis patterns of Enterococcus faecalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:969–972. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.969-972.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiller, G., and A. J. Gibbs. 1993. DIPLOMO: Distance Plot Monitor. [Online.] Australian National University. http://life.anu.edu.au/∼weiller/gfw.html. [October 1998, last date accessed.]