Abstract

AIM

To elucidate the question of whether the ocular trauma score (OTS) and the zones of injury could be used as a predictive model of traumatic and post traumatic retinal detachment (RD) in patients with open globe injury (OGI).

METHODS

A retrospective observational chart analysis of OGI patients was performed. The collected variables consisted of age, date, gender, time of injury, time until repair, mechanism of injury, zone of injury, injury associated vitreous hemorrhage, trauma associated RD, post traumatic RD, aphakia at injury, periocular trauma and OTS in cases of OGI.

RESULTS

Totally 102 patients with traumatic OGI with a minimum of 12mo follow-up and a median age at of 48.6y (range: 3-104y) were identified. Final best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was independent from the time of repair, yet a statistically significant difference was present between the final BCVA and the zone of injury. Severe trauma presenting with an OTS score I (P<0.0001) or II (P<0.0001) revealed a significantly worse BCVA at last follow up when compared to the cohort with an OTS score >III. OGI associated RD was observed in 36/102 patients (35.3%), whereas post traumatic RD (defined as RD following 14d after OGI) occurred in 37 patients (36.3%). OGI associated RD did not correlate with the OTS and the zone of injury (P=0.193), yet post traumatic RD correlated significantly with zone III injuries (P=0.013).

CONCLUSION

The study shows a significant association between lower OTS score and zone III injury with lower final BCVA and a higher number of surgeries, but only zone III could be significantly associated with a higher rate of RD.

Keywords: intraocular foreign body ocular trauma score, open globe injury, retina, retinal and vitreous surgery, retinal detachment, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Ocular trauma presents a prominent cause of visual impairment. The burden of blindness is related to both its inevitable effect on the quality of life and the loss of productivity that occurs in these subjects[1]–[2]. It can cause extreme psychological and emotional stress, as well as an economic burden to society. Worldwide, every year there are approximately 1.6 million people blinded from ocular injuries[3].

Modern intraocular surgical techniques have shifted the treatment of ocular trauma and allowed for vision to be salvaged in many formerly hopeless cases. It is important to accurately diagnose open globe injury (OGI) to enable prompt referral to ophthalmology for management and to correctly counsel the patient and his family. Previous studies have reported that the following prostnostic factors according to the OGI are of relevance: initial best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), adnexal trauma, mechanism or type of injury, zone of injury, relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), retinal detachment (RD), vitreous hemorrhage, uveal or retinal tissue prolapse, lens injury, hyphema and delay to surgery[4]–[5]. Well established is the fact that young male adults are primarly affected by open or closed globe injuries[6]–[7].

The Ocular Trauma Score (OTS) was suggested as a standardized categorical system for prediction of visual prognosis[8]. OTS is calculated based on six risk factors (initial vision, rupture, endophthalmitis, perforating injury, RD, and RAPD) and its usefulness for predicting final visual acuity (VA) has been validated by a number of studies[9]–[10]. The prognostic value of the OTS for injuries in adults is widely recognized[8].

The definitions described by Pieramici et al[11] on the localization of injury give important information on the prognosis and severity of trauma. A zone I injury is restricted to the cornea (including the limbus), a zone II injury includes the sclera no more than 5 mm posterior to the limbus, and a zone III injury is referred to scleral injury that are 5 mm posterior to the limbus. However, especially the state of the retina is essential for the long-term outcome of OGI-patients and RD during or after trauma limits the visual prognosis.

The aim of this study was to assess the prognostic value of the OTS and the zone of injury based on the definitions of Pieramici for predicting the likelihood of traumatic or post-traumatic RD. Further parameters like visual prognosis, number of surgeries required were also taken into consideration in our large cohort of patients in this one-year retrospective analysis.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Ethical Approval

Data acquisition and evaluation of data was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki (1991). This study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Association of Hamburg (PV7192) and an informed consent of the patients was not needed due to a retrospective, anonymized medical chart review.

We performed a retrospective observational chart analysis and identified 106 patients with OGI at the Medical University Center Hamburg-Eppendorf between 2010 and 2017 by searching the computerized institutional database. An OGI was referred to as a full-thickness structural break of the cornea, sclera, or both. Inclusion criteria of the retrospective analysis consisted of a follow-up of more than 1y. Four patients revealed an incomplete follow-up, therefore, a total of 102 charts were available for review and further statistical analysis. Ultrasonography was performed when indicated. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) was scheduled as needed.

Acquired demographic and clinical variables consisted of age, date, gender, time of injury, time until repair, mechanism of injury (rupture, laceration with further subdivision into foreign body penetration or perforation), zone of injury (zone I: corneal wound; zone II: corneoscleral injury within 5 mm of the limbus; zone III: corneoscleral wound ranging 5 mm from the limbus)[11]: injury-associated with vitreous hemorrhage, traumatic RD, post-traumatic RD (described as the occurrence of RD after a minimum of 14d), aphakia at injury, and periocular trauma. In order to evaluate a functional outcome, BCVA decimal at presentation and after a minimum of 12mo as well as the presence of afferent pupillary defect, was evaluated based upon chart review. The OTS categorical system for standardized assessment and visual prognosis associated with ocular injuries was also used. The OTS was developed by Kuhn et al[8] in 2002 and was based on the eye injury registry databases in the United States and Hungary. In addition, enucleation and the potential etiology (phthisis, pain) were evaluated accordingly.

Surgical Technique

All patients gave their informed consent prior to surgery. Primary enucleation or evisceration was not performed in a single case. A 360 degree conjunctival peritomy with blunt dissection of conjunctiva to identify scleral laceration was performed. Limbal and corneal laceration repair was performed using interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures. Scleral laceration were sutured with interrupted 7-0 vicryl sutures. The entire length of the scleral wound was explored and sutured. Incarceration of the uveal/choroidal tissue or retinal tissue into the scleral wound was either replaced or removed with Vannas scissors. Scleral cryopexy was performed at all sites the surgeon considered to be at high risk for retinal breaks. All lacerations were reevaluated for their integrity (Seidel test) after forming the anterior chamber with balanced salt solution (BSS). Subsequently, vitreoretinal surgery with or without lens extraction was performed at a later stage in indicated eyes.

No chandelier light was used. A complete vitrectomy was performed and in the presence of RD, vitreoretinal incarceration a necessary retinotomy or retinectomy was performed. In addition, a peripheral 360-degree endolaser was performed and a silicone oil endotamponade (5000 cSt) was applied.

Postoperative treatment consisted of a combined dexamethasone and gentamycin ointment four times daily as well as tropicamide eye drops once daily for two weeks.

Statistical Analysis

Statisical analysis were performed with SPSS software, version 27.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Demographic statistics were calculated for injury types and etiology and subsequently for all variables. A Pearson's Chi-square test was used to perform frequency analysis. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate differences in parametric variables and a Spearman rank test was used to correlate non parametric data. P values were evaluated in a two-sided fashion and a P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General Observations

In total 102 patients with traumatic OGI and a completed follow-up of more than 12mo [mean: 20.46mo (range: 12-105mo)] were identified and underwent further statistical analysis. The median age at presentation of injury was 48.6y (range: 3-104y) and 73.5% (75 of 102) of treated patients were male. Fifty percent (51 of 102) of injuries presented as perforating injuries followed by blunt rupture of the globe in 40.2% (41 of 102) and 9.8% by penetrating intraocular foreign body (IOFB) injuries (10 of 102).

Primary surgical repair was performed in 63 patients (61.8%) within 0-6h, 32 patients (31.4%) within 6-12h and 7 patients (6.9%) after 12-24h.

Functional Outcome and Associated Analysis

VA at presentation was documented in 97 patients and ranged between loss of vision [no light perception (NLP)] and 20/25. The majority of patients (82.3%) presented with a VA below 20/400. A moderate positive correlation (r=0.67, r2=0.23, P=0.00) between initial BCVA and BCVA at last follow-up was observed. In the case of a loss of vision (NLP) at presentation, BCVA improved in 54.5% until the follow-up. Enucleation (n=7) was only necessary in few cases at presentation, in which the globe was so severely damaged (e.g., loss of the entire retina), that recovery of any vision was deemed to be impossible and the patient developed a phthitic and painful eye.

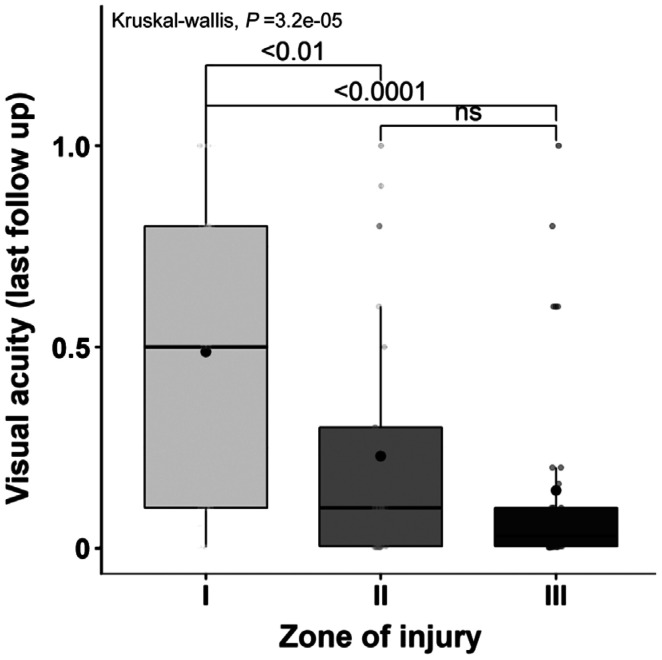

Final BCVA was independent from the time of repair (Table 1), yet a statistically significant difference was present between the final BCVA and the zone of injury. Patients presenting with a zone I injury had a statistically better final BCVA when compared to zone II (P<0.001) and zone III (P<0.0001) injuries (Figure 1).

Table 1. Association between final VA and the time to primary repair.

| Time to repair | n | Range | Mean | Median |

| 0-6h | 60 | 0/1.2 | 0.28±0.35 | 0.1 (0/0.6) |

| 6-12h | 27 | 0/1 | 0.31±0.36 | 0.1 (0.05/0.55) |

| 12-24h | 10 | 0/0.8 | 0.3±0.36 | 0.12 (0.01/0.68) |

VA: Visual acuity.

Figure 1. Association of final VA with zone of injury.

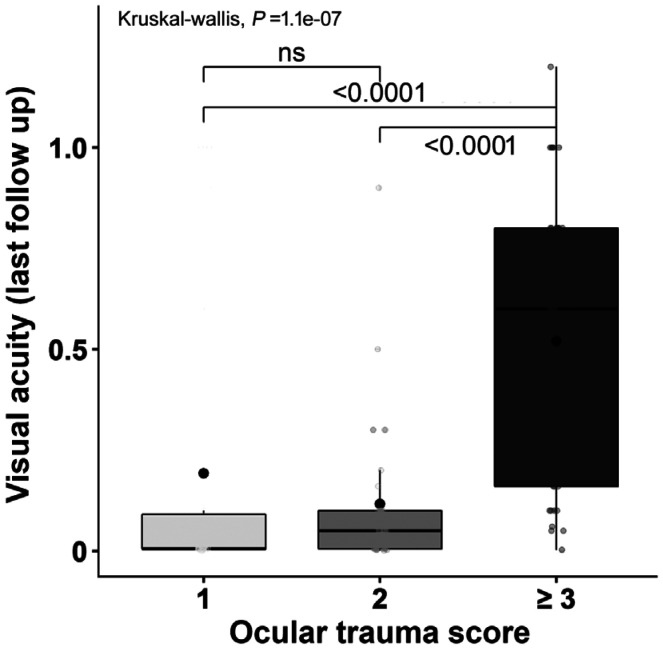

Correspondingly, severe trauma presenting with an OTS score I (P<0.0001) or II (P<0.0001) revealed a significantly worse BCVA at last follow up when compared to the cohort with an OTS score >III (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Association between final VA and OTS.

Zone of Injury

A zone I injury was documented in 34.3% (n=35) of patients, a zone II injury in 29.4% (n=30) of patients and a zone III injury in 36.3% (n=37) of patients. Traumatic RD was observed with increasing frequency. In 22.86% of zone I injury patients RD was observed, whereas 33.33% of zone II injury patients and 56.76% of zone III injury patients presented with an initial RD (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of traumatic RD in association with zone of injury.

| Zone of injury | Total number of cases | RD, n (%) |

|

| No | Yes | ||

| I | 35 | 27 (77.14) | 8 (22.86) |

| II | 30 | 20 (66.67) | 10 (33.33) |

| III | 37 | 16 (43.24) | 21 (56.76) |

RD: Retinal detachment. Chi-square test, P=0.010.

Additional surgeries due to post-traumatic RD was statistically more likely in patients with a zone III injury (P=0.013) when compared to a zone I injury. Of note, almost half of the patients (18 of 37 patients; 48.65%) with a zone III injury required additional surgical intervention due to post-traumatic RD (Table 3).

Table 3. Retreatment by zone of injury due to post traumatic RD.

| Zone of injury | Total number of cases | Retreatment, n (%) |

|

| No | Yes | ||

| I | 35 | 29 (82.86) | 6 (17.14) |

| II | 30 | 17 (56.67) | 13 (43.33) |

| III | 37 | 19 (51.35) | 18 (48.65) |

RD: Retinal detachment. Chi-square test, P=0.013.

Retinal Detachment

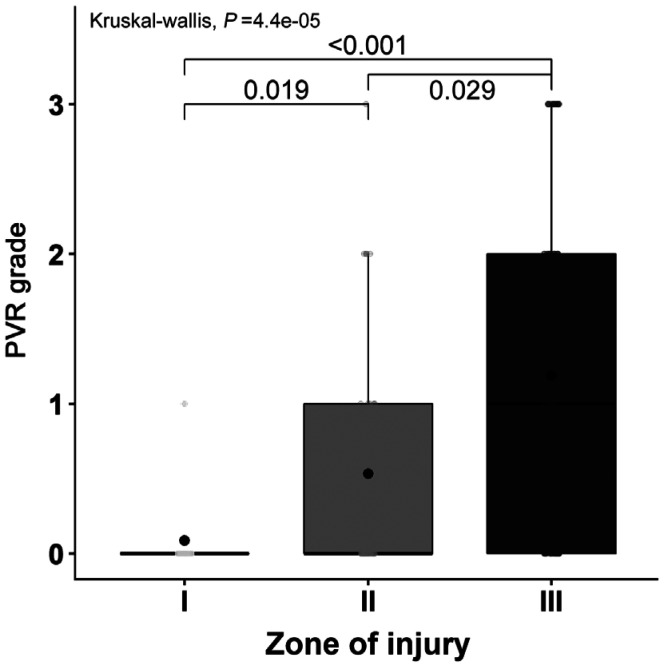

OGI-associated RD was observed in 36/102 patients (35.3%), whereas post-traumatic RD (defined as RD occuring 14d after OGI) occurred in 37 patients (36.3%). OGI-associated RD did not correlate with the OTS and the zone of injury, yet post-traumatic RD, as outlined previously correlated significantly with zone III injuries (Table 3). The development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) was statistically more frequently observed in patients with zone III injuries in comparison to zone I injuries (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Association between PVR grade and zone of injury.

DISCUSSION

OGI belong to the most severe eye injuries, but their prognoses are very heterogeneous and depend on multiple factors[12]. Treatment costs for OGI are high, including expensive surgeries and procedures, long admission time in the hospital, compensation payment to the injured patients, and loss of working days[3]. The final visual outcome among OGI patients ranges from full recovery to complete blindness or even loss of the affected globe[13]–[14].

OGI with RD are a subgroup of particularly severe injuries that can be expected to have an even worse prognosis than OGI without RD. The visual prognosis is extremely guarded in part because of a high prevalence of posterior segment complications such as PVR. Stryjewski et al[15] reported an RD rate of 29% in a series of approximately 900 OGIs. After an OGI, a PPV is often indicated in the setting of posttraumatic endophthalmitis, IOFB, media opacity, vitreoretinal traction, retinal incarceration, and RD.

Surgical timing is an important consideration in the treatment of ocular injuries and may play a critical role in the final outcome, but the timing of the intervention remains controversial. The standard practice worldwide is to conduct primary surgical repair at the earliest opportunity (in the first 24h) to preserve the structural integrity of the globe. PPV is often undertaken several days to weeks later. Most patients need on average two surgeries, and the most common surgeries performed after OGI repair are PPV, lensectomy, anterior vitrectomy, anterior chamber washout, IOL insertion, enucleation, and other vitreoretinal operations (laser, membrane peeling, cryotherapy, silicone oil tamponade, and gas injection).

PPV within one to two weeks (as we prefer as well) is recommended, because it is associated with a significant reduction of RD risk resulting from PVR and better BCVA[2],[16]–[18], whereas delayed vitrectomy (10-14d from the time of injury) seems to be a significant risk for the development of PVR, which leads to recurrent RD[19]–[22]. The benefit of early intervention with PPV is to remove the maximum amount of vitreous, thus eliminating the depot for inflammation (and reduce the risk of PVR) to settle and epiretinal membranes to form. Other authors contend for delayed intervention, allowing time for the eye to recover, a complete posterior vitreous detachment to develop, and the PVR process to settle, thus making the surgery less complicated[23]–[27].

The results of our study show that prompt primary repair of the OGI in the first 24h was performed in the majority of cases, but interestingly the timing of intervention within the cohort was not associated with final BCVA. A major risk factor of RD and subsequently decreased final BCVA is the development of PVR. We conclude that the development of PVR is independent of timing of surgery and is instead influenced by the zone of injury (Tables 2 and 3).

The majority of patients in our cohort were male, which is in agreement with other studies. A male preponderance is a universal characteristic of eye trauma and is thought to be related to occupational exposure, participation in dangerous sports and hobbies, alcohol usage and risk-taking behavior. This might be due to gender-based behavior and male involvement in working activities with a higher risk for injuries[28]–[30].

Our study found a moderate positive correlation between initial and final BCVA. Better initial BCVA conceivably reflects milder ocular tissue damage, thus ensuring better visual outcome. On the contrary, an initially poor BCVA or even NLP suggests serious ocular tissue destruction, particularly of the retina and optic nerve[31]–[32].

The most widely used predictive model in ocular trauma is the validated OTS, which predicts final visual potential after OGI and provides the treating ophthalmologist with realistic expectations of the visual potential and, subsequently in deciding among various management strategies[8]. A patient with OTS category one will have a higher risk of poorer final VA in contrast to a patient with OTS category five who will have a higher probability of a better final VA[8].

One of the aims of our study was to elucidate the possibility of using the OTS as an RD predictive model. In our study, we found a significant association between lower OTS and lower initial BCVA and between lower OTS and a higher number of ensuing surgeries (Figure 2). However, there was no association between lower OTS and higher RD rate. Our findings are in accordance with the results of Man and Steel[33] that suggested that OTS potentially had a predictive value of the final BCVA in OGI but not for RD.

The findings of our study can support the assumption that zone of injury as defined by Pieramici et al[11] is a reliable predictive factor for RD. Zone III injuries were significantly associated with a higher number of surgeries, lower initial and final BCVA, a higher-trauma induced RD rate and post-traumatic PVR RD rate compared to zone I injuries (Tables 2 and 3).

A zone II or III wound resulted in significantly higher rates of poor visual outcome than those involving zone I OGIs. Correspondingly, Madhusudhan et al[28] predicted a 20 times the risk of having poor final VA in zone III injuries when compared zone I injuries. This could be explained by the fact that posterior wounds could cause irreparable damage to photoreceptors[28]. According to Pieramici et al[11], Thakker and Ray[34] and Phillips et al[35], posterior OGIs are particularly serious since a zone II and/or III injury is more likely than a zone I injury to be associated with RD, phthisis, enucleation, and worse final VA.

Sympathetic ophthalmia with potential for bilateral blindness is nowadays a rare indication for enucleation of an injured eye as most cases of sympathetic ophthalmia can today be controlled by corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants[36]. Most reported cases (65%) occur between two weeks to two months after injury and sympathetic ophthalmia are rare during the first two weeks after trauma[37]. As such primary surgical repair should not be abandoned for the risk of sympathetic ophthalmia in eyes with NLP. In our case series there were no cases of sympathetic ophthalmia and all enucleations (seven cases) were performed in non-salvable eyes after primary surgical repair and after vitrectomy (RD non sanata and phthisis bulbi).

Which patients are at higher risk of RD and in need of continued monitoring by a retina specialist? Reliable predictive models are essential in the treatment of such complex cases. To quantify this risk of RD, we tried to elucidate the question of whether the OTS and the zones of injury could be used as a predictive model of RD. Both models are widely used and established. Our study showed a significant association between lower OTS score and zone III injury with lower final BCVA and a higher number of surgeries, but only zone III could be significantly associated with a higher rate of RD.

A number of novel and reliable models are being developed to help address this question. Brodowska et al[16] reported on a clinical prediction model that was developed at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary to predict the risk of RD after OGI. The ability to reliably predict the likelihood of a patient developing an RD after OGI has implications for expectation setting, counseling, follow-up, and surgical planning.

The drawback of our study is its retrospective nature. However all patients had a one year follow-up, the models used to evaluate RD are simple and all of the patients underwent surgery with the same two experienced surgeons. Thus, further studies may be necessary to identify predictors for the occurrence and outcome of traumatic and post-traumatic RD. We hope that the results of our study could help fellow ophthalmologists to treat and monitor OGI patients closely and safely.

Acknowledgments

Authors' contributions: Data acquisition (Dulz S, Dimopoulos V, Kromer R); Statistical analysis (Dulz S, Bigdon E, Kromer R); Manuscript preparation (Dulz S, Katz T, Kromer R, Skevas C); Internal review (Dulz S, Katz T, Spitzer MS, Skevas C).

Conflicts of Interest: Dulz S, None; Dimopoulos V, None; Katz T, None; Kromer R, None; Bigdon E, None; Spitzer MS, None; Skevas C, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eballe AO, Epée E, Koki G, Bella L, Mvogo CE. Unilateral childhood blindness: a hospital-based study in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:461–464. doi: 10.2147/opth.s5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.May DR, Kuhn FP, Morris RE, Witherspoon CD, Danis RP, Matthews GP, Mann L. The epidemiology of serious eye injuries from the United States Eye Injury Registry. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238(2):153–157. doi: 10.1007/pl00007884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Négrel AD, Thylefors B. The global impact of eye injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5(3):143–169. doi: 10.1076/opep.5.3.143.8364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal R, Rao G, Naigaonkar R, Ou XL, Desai S. Prognostic factors for vision outcome after surgical repair of open globe injuries. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(6):465–470. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.86314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauza AM, Emami P, Soni N, Holland BK, Langer P, Zarbin M, Bhagat N. A 10-year review of assault-related open-globe injuries at an urban hospital. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(3):653–659. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laatikainen L, Tolppanen EM, Harju H. Epidemiology of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in a Finnish population. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1985;63(1):59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1985.tb05216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strahlman E, Elman M, Daub E, Baker S. Causes of pediatric eye injuries. A population-based study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(4):603–606. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070060151066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn F, Maisiak R, Mann L, Mester V, Morris R, Witherspoon CD. The ocular trauma score (OTS) Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15(2):163, 165,vi. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dosková H. Evaluation of results of the penetrating injuries with intraocular foreign body with the Ocular Trauma Score (OTS) Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2006;62(1):48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unver YB, Kapran Z, Acar N, Altan T. Ocular trauma score in open-globe injuries. J Trauma. 2009;66(4):1030–1032. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181883d83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pieramici DJ, Sternberg P, Jr, Aaberg TM, Sr, Bridges WZ, Jr, Capone A, Jr, Cardillo JA, de Juan E, Jr, Kuhn F, Meredith TA, Mieler WF, Olsen TW, Rubsamen P, Stout T. A system for classifying mechanical injuries of the eye (globe). The Ocular Trauma Classification Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(6):820–831. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acar U, Tok OY, Acar DE, Burcu A, Ornek F. A new ocular trauma score in pediatric penetrating eye injuries. Eye (Lond) 2011;25(3):370–374. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng K, Hu YT, Ma ZZ. Prognostic indicators for no light perception after open-globe injury: eye injury vitrectomy study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(4):654–662.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tok O, Tok L, Ozkaya D, Eraslan E, Ornek F, Bardak Y. Epidemiological characteristics and visual outcome after open globe injuries in children. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2011;15(6):556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stryjewski TP, Andreoli CM, Eliott D. Retinal detachment after open globe injury. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodowska K, Stryjewski TP, Papavasileiou E, Chee YE, Eliott D. Validation of the retinal detachment after open globe injury (RD-OGI) score as an effective tool for predicting retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(5):674–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleary PE, Ryan SJ. Vitrectomy in penetrating eye injury. Results of a controlled trial of vitrectomy in an experimental posterior penetrating eye injury in the rhesus monkey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(2):287–292. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010289014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Entezari M, Rabei HM, Badalabadi MM, Mohebbi M. Visual outcome and ocular survival in open-globe injuries. Injury. 2006;37(7):633–637. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman DJ. Early vitrectomy in the management of the severely traumatized eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93(5):543–551. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He Y, Zhang L, Wang F, Zhu MD, Wang Y, Liu Y. Timing influence on outcomes of vitrectomy for open-globe injury: a prospective randomized comparative study. Retina. 2020;40(4):725–734. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin Y, Chen HJ, Xu XJ, Hu YT, Wang CG, Ma ZZ. Traumatic proliferative vitreoretinopathy: clinical and histopathological observations. Retina. 2017;37(7):1236–1245. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhn F. Strategic thinking in eye trauma management. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittra RA, Mieler WF. Controversies in the management of open-globe injuries involving the posterior segment. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;44(3):215–225. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson JT, Parver LM, Enger CL, Mieler WF, Liggett PE. Infectious endophthalmitis after penetrating injuries with retained intraocular foreign bodies. National Eye Trauma System. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(10):1468–1474. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardillo JA, Stout JT, LaBree L, Azen SP, Omphroy L, Cui JZ, Kimura H, Hinton DR, Ryan SJ. Post-traumatic proliferative vitreoretinopathy. The epidemiologic profile, onset, risk factors, and visual outcome. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(7):1166–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan SJ. Results of pars plana vitrectomy in penetrating ocular trauma. Int Ophthalmol. 1978;1(1):5–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00133272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aylward GW. Vitreous management in penetrating trauma: primary repair and secondary intervention. Eye (Lond) 2008;22(10):1366–1369. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madhusudhan AP, Evelyn-Tai LM, Zamri N, Adil H, Wan-Hazabbah WH. Open globe injury in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia - a 10-year review. Int J Ophthalmol. 2014;7(3):486–490. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.03.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teixeira SM, Bastos RR, Falcão MS, Falcão-Reis FM, Rocha-Sousa AA. Open-globe injuries at an emergency department in Porto, Portugal: clinical features and prognostic factors. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014;24(6):932–939. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal R, Ho SW, Teoh S. Pre-operative variables affecting final vision outcome with a critical review of ocular trauma classification for posterior open globe (zone III) injury. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(10):541–545. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.121066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rofail M, Lee GA, O'Rourke P. Prognostic indicators for open globe injury. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34(8):783–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unal MH, Aydin A, Sonmez M, Ayata A, Ersanli D. Validation of the ocular trauma score for intraocular foreign bodies in deadly weapon-related open-globe injuries. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2008;39(2):121–124. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20080301-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu Wai Man C, Steel D. Visual outcome after open globe injury: a comparison of two prognostic models—the Ocular Trauma Score and the Classification and Regression Tree. Eye (Lond) 2010;24(1):84–89. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thakker MM, Ray S. Vision-limiting complications in open-globe injuries. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41(1):86–92. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(06)80074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips HH, Blegen Iv HJ, Anthony C, Davies BW, Wedel ML, Reed DS. Pars plana vitrectomy following traumatic ocular injury and initial globe repair: a retrospective analysis of clinical outcomes. Mil Med. 2021;186(Suppl 1):491–495. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usaa286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aziz HA, Flynn HW, Jr, Young RC, Davis JL, Dubovy SR. Sympathetic ophthalmia: clinicopathologic correlation in a consecutive case series. Retina. 2015;35(8):1696–1703. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makley TA, Jr, Azar A. Sympathetic ophthalmia. A long-term follow-up. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(2):257–262. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050125004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]