Abstract

Aims

This work attempts to develop a standalone heart rhythm alerting system for the intensive care unit (ICU), where life-threatening arrhythmias have to be identified/alerted more precisely and more instantaneously (i.e. with lower latency) than existing bedside monitors.

Methods and results

We use the dataset from the PhysioNet 2015 Challenge, which contains records that led to true and false arrhythmic alarms in the ICU. These records have been re-annotated as one of eight classes, namely (i) asystole, (ii) extreme bradycardia, (iii) extreme tachycardia, (iv) ventricular fibrillation (VF), (v) ventricular tachycardia (VT), (vi) normal sinus rhythm, (vii) sinus tachycardia, and (viii) noise/artefacts. Arrhythmia-specific features and features that measure the signal quality were extracted from all the records. To improve VF detection, an improved, over an existing, single-lead R-wave detection was developed that takes into account the R-waves detected in all electrocardiographic (ECG) leads. To avoid false R-wave detection due to pacing spikes, ECG signals were filtered with a low pass filter prior to R-wave detection, while the raw signals were used for feature extraction. Random forest was used as the classifier, and 10-time five-fold cross-validation, resulted in a macro-average sensitivity of 81.54%.

Conclusions

In conclusion, comparing with the bedside monitors used in the PhysioNet 2015 competition, we find that our method achieves higher positive predictive values for asystole, extreme bradycardia, VT, and VF; furthermore, our method is able to alert the presence of arrhythmia instantaneously, i.e. up to 4 s earlier.

Keywords: Bedside monitors, Multi-class classification, Artificial intelligence, Machine learning, Feature engineering, Signal processing

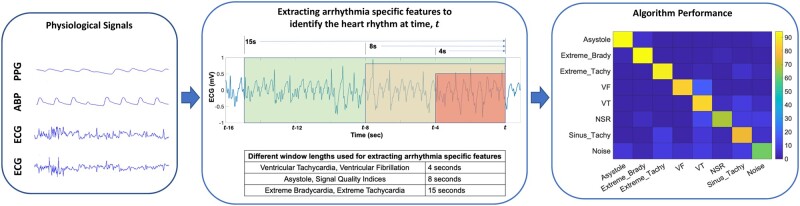

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Electrocardiographic (ECG) signals remain the most important means of capturing cardiac activity in real time for the monitoring of intensive care unit (ICU) patients. While existing bedside monitors are designed to raise alarms whenever the ECG recordings go out of the normal range, a persistent drawback is that most of the alarms raised by the bedside monitors are false alarms, creating an unnecessarily noisy environment and contributing to alarm fatigue.1

The ‘PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2015: Reducing False Arrhythmia Alarms in the ICU’2 was specifically designed to foster the development of new methods to filter out false alarms for asystole, bradycardia, tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia (VT), and ventricular fibrillation (VF). The PhysioNet data included physiological signals of 2-lead ECG, arterial blood pressure (BP), and photoplethysmography (PPG). From this challenge,3–6 several methods were created that were based upon the prior knowledge of the alarms’ annotation from the bedside monitor; i.e. they were all designed to be used as a second stage classifier/filter, after the bedside monitor has raised an alarm. Since these methods were only built to filter out the false alarms of five specific heart rhythms, the design/training of these methods were limited to small data sets corresponding to the signal records that the bedside monitors considered to be abnormal. This raises the question on whether these methods could, by themselves, truly identify an abnormal heart rhythm from all other heart rhythm classes.

Multi-class heart rhythm classification of ECG signals has been a persistently challenging problem, and machine learning (ML) techniques have been essential in providing improved outcomes.7,8 One of the first attempts for arrhythmia analysis was by Guvenir et al.,9 who used supervised ML to classify 12-lead ECG signals to 16 classes, and achieved a 10-fold cross-validation accuracy of 68%. The authors published the extracted feature values from their data to the University of California Irvine repository,10 and later other studies have tested their methods on these data.11,12 Recently, the ‘China Physiological Signal Challenge (CPSC) 2018’13 provided a large, open repository of 6877 raw 12-lead ECG recordings, with the intent of building a classifier that can accurately sort the ECG recordings into nine classes (normal heart rhythm or one of the eight abnormal heart rhythms). The winner of the challenge14 used convolutional neural networks to achieve a median F-1 score of 0.84.

Many popular studies15–18 on multi-class classification of ECG rhythms/beats have utilized the data recorded from ambulatory devices or single-lead ECG devices. Among these, Hannun et al.15 used a 34 layered convolutional neural network for detecting 10 heart rhythm classes from one sec of ECG signal from an ambulatory device. Due to the 1 s limitation, the model missed out some important heart rhythms that require more time for detection, e.g. sinus bradycardia, asystole. The ‘AF Classification from a Short Single Lead ECG Recording—The PhysioNet Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2017’19 encouraged the development of methods which could identify from a single short ECG lead recording (30–60 s), whether it shows normal sinus rhythm (NSR), atrial fibrillation (AF), an alternative rhythm, or it is too noisy to be classified. The two best scorers20,21 from this challenge used stacked classifiers, wherein first a deep learning-based classifier was used to obtain the classification result and the confidence score with which the classification was made; if the confidence score was below a defined threshold, the second classifier using handcrafted features was used to determine the class. It should be noted that most arrhythmia classification methods have analysed only the morphology of ECG signals to determine the heart rhythm. However, critical life-threatening arrhythmias—such as VT and VF—can be detected more accurately by including the BP signal.22

In this manuscript, we propose a standalone, real-time processing platform that can detect and categorize life-threatening heart rhythms by analysing the ECG, BP, and PPG signals of ICU patients, into one of the multiple classes, such as VT, VF, extreme tachycardia, extreme bradycardia, and asystole. We use signal processing techniques and ML to provide more precise and instantaneous alerts of life-threatening arrhythmias. Additionally, sinus tachycardia, NSR, and noise/artefacts have been included as one of the possible output classes.

Methods

Dataset

We used data from the ‘PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2015: Reducing False Arrhythmia Alarms in the ICU’. The challenge data were sourced from four hospitals in the USA and Europe, and employed bedside monitors from three manufacturers; furthermore, it was ensured that no manufacturer or hospital contributed to more than half of the records. The data were made public and are available at https://physionet.org/content/challenge-2015/1.0.0/ (28 June 2021). The database includes records of 300 s long physiological signals from ICU patients, taken just prior to the time when an alarm was raised by the bedside monitor. The physiological signals included were: 2-lead ECG, BP, and the PPG. We re-annotated each of these events as belonging to one of the following categories: (i) asystole, (ii) extreme bradycardia, (iii) extreme tachycardia, (iv) VF, (v) VT, (vi) NSR, (vii) sinus tachycardia, and (viii) noise/artefact. The definitions/criteria for asystole, extreme bradycardia, extreme tachycardia, VT, and VF were taken from the PhysioNet 2015 challenge2 and are listed in Table 1. More information regarding the dataset is available in the Supplementary material online.

Table 1.

Definitions of the eight classes

| Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| Asystole | A gap of at least 4 s between two successive R-waves |

| Extreme bradycardia | A heart rate lower than 40 beats per minute for four consecutive beats |

| Extreme tachycardia | A heart rate higher than 140 beats per minute for 17 consecutive beats |

| Ventricular fibrillation | An oscillatory ECG waveform of at least 4 s |

| Ventricular tachycardia | Five consecutive VT beats with heart rate of at least 100 beats per minute |

| Normal sinus rhythm | A heart rate between 60 and 100 beats per minute for 15 s |

| Sinus tachycardia | A heart rate between 100 and 140 beats per minute for 17 consecutive beats |

| Noise/artefacts | All physiological signals are filled with noise or artefacts |

R-wave detection

We used the R-wave peak detection method described by Martinez et al.23 The method identifies peaks based on the morphological characteristics of the ECG signal, and works well in most ECG records. To further improve R-wave peak detection that could impact the accurate detection of complex rhythms e.g. VF, we have developed a multi-lead moving window method, which is described in detail in the Supplementary material online.

To avoid the scenario, that pacing spikes and other high-frequency noise are identified as R-wave peaks, we designed a finite impulse response low-pass filter in MATLAB. The filter has 51 taps and a cut-off frequency of 15 Hz. The raw ECG signal is, accordingly, passed through the low-pass filter, and the filtered signal is used by the multi-lead moving window-based R-wave peak detector. Once the R-wave peak locations are identified, features are extracted from the raw ECG signal.

Feature extraction

Feature extraction was performed on ECG, BP, and PPG signals. We extracted a set of signal quality indexes (SQIs) to indicate if the signals are appropriate for further processing or are noisy. Furthermore, a set of arrhythmia-specific features, which characterize each arrhythmia class, was also extracted (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of extracted features that were fed to the eight-class Random Forest Classifier

| Signal | Feature | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocardiogram |

|

Signal quality indices (8 s) |

|

Asystole features (8 s) | |

|

Extreme bradycardia features (15 s) | |

|

Extreme tachycardia features (15 s) | |

|

VF features (4 s) | |

|

VT features (4 s) | |

| Blood pressure |

|

Signal quality indices (8 s) |

| Max period between consecutive onsets of waveform | Asystole feature (8 s) | |

|

Extreme bradycardia features (15 s) | |

|

Extreme tachycardia features (15 s) | |

|

VF/VT features (4 s) | |

| PPG |

|

Signal quality indices (8 s) |

|

Asystole features (8 s) | |

|

Extreme bradycardia features (15 s) | |

|

Extreme tachycardia features (15 s) | |

| Decreasing PPG | VF/VT features (4 s) |

Column ‘Signal’ indicates the physiological signal from which the features are extracted, and column ‘Feature’ provides the name of each feature. Column ‘Category’ provides the context behind the features’ utility. The features have been broadly categorized into six categories: (i) signal quality indices which indicate the quality of the signal (clean or noisy) and are computed over 8 s of signal, (ii) asystole features which characterize asystole and are computed over 8 s of signal, (iii) extreme bradycardia features which characterize extreme bradycardia and are computed over 15 s of signal, (iv) extreme tachycardia features which characterize extreme tachycardia and are computed over 15 s of signal, (v) ventricular fibrillation (VF) features which characterize VF and are computed over 4 s of signal, and (vi) ventricular tachycardia (VT) features which characterize VT and are computed over 4 s of signal. The set of ECG features were computed from each lead, separately. Thus, a total of 74 features (26 features from ECG lead 1, 26 features from ECG lead 2, 10 features from BP, and 12 features from PPG) were used here, for heart rhythm classification.

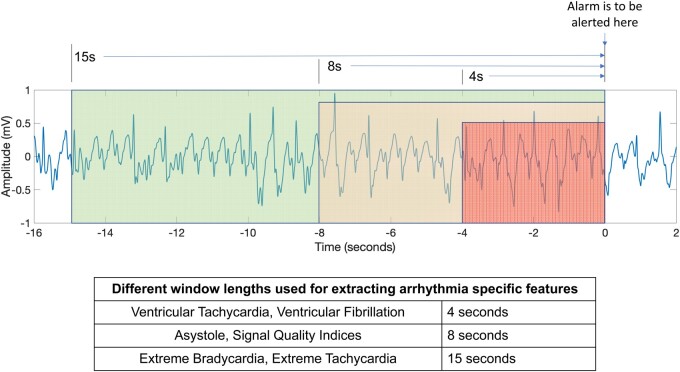

Many of these features have been used in our recent study on the reduction of false arrhythmia alarms in the ICU when one has prior knowledge of the type of the alarm22; more details about the features can be found in the Supplementary material online of that paper. A major objective of our work is to perform real-time identification of patients’ heart rhythms. An implied sub-objective is that detection of these heart rhythms has to happen as soon as the arrhythmia pattern criteria are met, so that a timely alarm is raised. By observing the data/annotations from the PhysioNet 2015 challenge data, we realized that the alarms raised by the bedside monitors can sometimes be delayed several seconds after the abnormal heart rhythm criteria have been met. To achieve ‘instant’ detection, we defined window length requirements for each heart rhythm class. For example, 4 s of vital sign signals is sufficient to determine whether or not the patient is having VT/VF. Similarly, 8 s is sufficient to determine if a patient is experiencing asystole. Finally, we found that 15 s is an appropriate window-length to determine if the patient is suffering from extreme bradycardia or extreme tachycardia. Accordingly, the corresponding arrhythmia-specific features of extreme tachycardia, extreme bradycardia, asystole, VT, and VF were computed from signals of 15 s, 15 s, 8 s, 4 s, and 4 s window-lengths, respectively. The idea is pictorially presented in Figure 1, and the motivation for having different window lengths is illustrated in the Supplementary material online.

Figure 1.

Presentation of the different window-length strategy used in extracting arrhythmia-specific features characterizing different heart rhythms.

Whenever one or more physiological signals were absent or noisy, while computing features the corresponding feature values were assigned NANs (missing values). The SQIs were designed such that for noisy signals they would either have low values or be rendered as not-a-number (NAN).

Machine learning-random forest algorithm

We tried multiple supervised ML algorithms for classification, namely artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF) classifiers. We have found that the RF classifier gave the best classification performance.

In a scenario in which one or more vital sign signals could be noisy, resulting in many missing feature values, the ability of a classifier to handle missing data is of high importance. The RF classifier has an in-built ability to directly handle missing data, while other classification algorithms, namely SVM and ANN need data imputation techniques to fill in the missing values, before they can be used for training and testing over the data. RF is an ensemble learning method that can be used for either regression or classification. More details regarding the ML RF algorithm are included in the Supplementary material online.

Results

10-time five-fold cross-validation

We performed five-fold cross-validation (with stratified random sampling) on the available data to estimate our method’s performance on the unseen data. To account for the stochastic differences during cross-validation, we assessed the five-fold cross-validation performance of our method 10 times, and then took the mean performance.

Performance metrics

The sum of the confusion matrices derived from each five-fold cross-validation were summed up and are presented in Table 3. Performance metrics, namely overall accuracy, macro-average sensitivity, macro-average positive predictive value (PPV), sensitivity of each class, PPV of each class, and the most common misclassification (when misclassified, which class instead is most chosen as the result), were derived from the confusion matrix, and have been noted in Table 4. Overall accuracy is defined as the ratio of all the true positives and true negatives, to the total number of all records. Sensitivity for each class is defined as the ratio of the number of true positives to the total number of records of that class. PPV for each class is defined as the ratio of the number of true positives to the total number of true positives and false positives of that class. Macro-average sensitivity is simply the sum of sensitivities of all classes divided by the total number of classes; similarly, macro-average PPV is the sum of PPVs of all classes divided by the number of classes.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix of the eight-class classification result after 10-time five-fold cross-validation

| Prediction |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asystole | Extreme brady | Extreme tachy | VF | VT | NSR | Sinus tachy | Noise/artefacts | ||

| Ground truth | Asystole | 178 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Extreme brady | 10 | 472 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 1 | |

| Extreme tachy | 0 | 0 | 1078 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 60 | 20 | |

| VF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| VT | 0 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 784 | 29 | 72 | 31 | |

| NSR | 56 | 198 | 33 | 14 | 580 | 3390 | 378 | 381 | |

| Sinus tachy | 1 | 31 | 193 | 1 | 134 | 61 | 1700 | 99 | |

| Noise/artefacts | 42 | 17 | 57 | 32 | 55 | 21 | 54 | 432 | |

Table 4.

Sensitivity, most common misclassification, positive predictive value (PPV) for each rhythm, and precision observed by bedside monitors. NA: Not available

| Rhythm | Sensitivity (%) | Most common misclassification [error rate (%)] | PPV (%) | PPV (%) Physionet 2015 challenge | PPV (%) MIMIC II study | PPV (%) UCSF study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asystole | 93.7 | Extreme bradycardia (4.74) | 62.0 | 16.67 | 9.33 | 32.83 |

| Extreme bradycardia | 94.4 | NSR (2.00) | 64.5 | 50 | 70.71 | NA |

| Extreme tachycardia | 91.4 | Sinus tachycardia (5.08) | 78.8 | 94.92 | 76.93 | NA |

| VF | 83.8 | VT (16.2) | 57.8 | 10.34 | 20.33 | 67.72 |

| VT | 84.3 | Sinus tachycardia (7.74) | 49.2 | 26.23 | 53.42 | 13.00 |

| NSR | 67.4 | VT (11.53) | 96.6 | NA | NA | NA |

| Sinus tachycardia | 76.6 | Extreme tachycardia (8.69) | 75.1 | NA | NA | NA |

| Noise/artefacts | 60.8 | Extreme tachycardia (8.03) | 44.7 | NA | NA | NA |

Algorithm performance evaluation

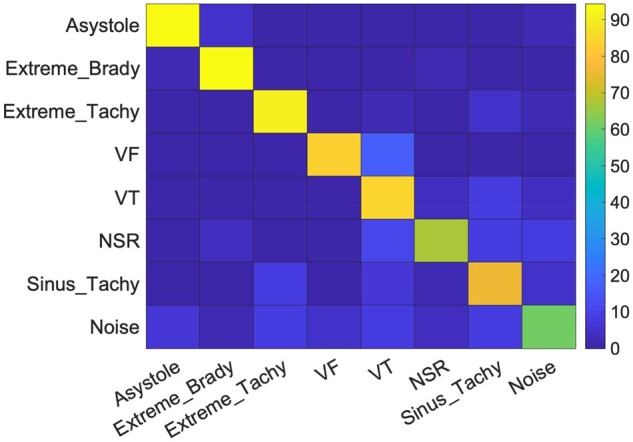

Our algorithm consistently performed well in identifying all arrhythmias. The confusion matrix of the 8-class classification results after 10-time five-fold cross-validation is presented in Table 3. We have been able to achieve an overall accuracy of 74.7%. The macro-average sensitivity equalled 81.5% and the macro-average PPV equalled 66.1%. For asystole, extreme bradycardia, and extreme tachycardia, the method achieved a sensitivity of 91.4% or above. The method achieved a sensitivity of 83.8% for VF and a sensitivity of 84.3% for VT. An important note here is that all the unidentified VF cases were classified as VT, which also is a serious life-threatening arrhythmia. In other words, an alarm was raised for 100% of the VF cases.

Figure 2 shows the heat map of our results, to pictorially depict the confusion matrix. It can be observed that the classifier did well in classifying the five types of life-threatening arrhythmias, with sensitivities exceeding 83.8%. Many of the errors made by the classifier were understandable. The most common misclassification of extreme tachycardia was sinus tachycardia, of sinus tachycardia was extreme tachycardia, and of extreme bradycardia was NSR; all these classes are similar morphologically and differ only by heart rate. We found that most of these misclassifications were actually borderline cases, in which the heart rate hovered around the cut-off between classes. If required, the classification result can be enhanced by performing a simple secondary check on the heart rate. Another understandable error is that the most common misclassification result for asystole is extreme bradycardia. The error is understandable because asystole causes the mean heart rate to drop significantly. Furthermore, since extreme bradycardia is also a life-threatening arrhythmia and an alarm is raised for it, the error is not very concerning clinically.

Figure 2.

Heat map to pictorially show our method’s mean classification performance across 10-time five-fold cross-validation.

The proposed method did not perform well in classifying NSR and noise/artefacts. In our attempt to achieve high sensitivity in detecting an arrhythmia, many NSR cases were misclassified as arrhythmia; incidentally, the majority of the false positives in asystole, extreme bradycardia, and sinus tachycardia classes belonged to the NSR class. Our experiments were performed on acausal records of different arrhythmic events and NSR; studies suggest that such experiments may present over-optimistic results on false alarm suppression, and when implemented in real time, they may exhibit higher false alarm rates and poorer NSR classification performance.24 To assess this algorithm for such scenario, we identified long, continuous NSR segments (noise free signals, at a heart rate 40–100 b.p.m.) from the Physionet 2015 competition, that were not used for training/validation (amounting to ∼28.5 K s of data), and evaluated the five classifiers trained over the five-fold training-sets, on these new NSR segments. The classifiers identified the heart rhythm in a causal manner, once every sec, and alarms raised in close succession (i.e. within the next 15 s) were treated as the same alarm (no new alerts were raised). Our algorithm achieved a mean classification accuracy of 84.29% in identifying NSR, which is higher than that reported in Table 3. With the above settings, we estimate experiencing ∼374 false alarms per patient, per day.

The class with the poorest performance was noise/artefacts, with a sensitivity of only 60.8%. Not surprisingly, we found that correctly identifying noise/artefacts is challenging, as noise appears in a wide variety of forms, such as flat line, high frequency noise, or fluctuating readings. We therefore found it difficult to design features that can consistently identify all forms of noise. One other error of particular concern was that 7.74% of VT events were misclassified as sinus tachycardia, which does not raise an alarm and thus could be of clinical consequence.

In Table 5, we can see that there is significant imbalance in the number of cases for each arrhythmia. The classification results however indicate that the supervised ML model is fairly not affected by the class imbalance.25

Table 5.

Number of events in each of the eight classes

| Class | Number of events |

|---|---|

| Asystole | 19 |

| Extreme bradycardia | 50 |

| Extreme tachycardia | 118 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 8 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 93 |

| Normal sinus rhythm | 503 |

| Sinus tachycardia | 222 |

| Noise or artefacts | 71 |

While extracting the arrhythmia-specific features from different sized windows of signals, though rare, a case may arise wherein two arrhythmia criteria are being satisfied simultaneously. For example, a case of asystole (window-length 8 s) may simultaneously satisfy the criterion of extreme bradycardia (window-length of 15 s). This is not a major limitation, since asystole and extreme bradycardia, are both life-threatening arrhythmias and an alarm is raised for both heart rhythms.

Algorithm performance comparison with bed-side monitors

While it is hard to compare our classifier’s sensitivities for life-threatening arrhythmias with ICU monitors (these data are not available), sensitivities of at least 83.8% are nonetheless very encouraging. We now compare the PPVs of our proposed system to those of the bedside monitors used in the PhysioNet 2015 challenge,2 MIMIC II study,26 and the alarm fatigue study from UCSF27 (Table 4). It is important to note that the PPVs mentioned here for the bedside monitors are based purely on the empirical observations of the number of true alarms to the total number of alarms. Furthermore, we are assuming that the alarm records included in each of these studies accurately reflected the monitors’ actual abilities to discriminate true from false alarms. All PPVs were computed by taking the ratio of the number of true alarms to the total number of alarms raised for the relevant arrhythmia. In comparing the various PPVs, the proposed algorithm achieves higher PPVs for most life-threatening arrhythmias. Across the five life-threatening arrhythmias, the proposed algorithm achieved a macro average PPV of 62.46%; in comparison, the monitors in the PhysioNet 2015 challenge achieved a PPV of 39.63% and the Philips monitors in the MIMIC II study achieved a PPV of 57.26%. With regard to the UCSF study, we compared the algorithm performance across only asystole, VF and VT; the macro-average PPV of our algorithm was 51.53% and that of the GE bedside monitors in UCSF study was 18.06%.

Following AAMI (Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation) recommendations, Philips Healthcare demonstrated their ‘ST/AR’ (ST-segment and arrhythmia) algorithm (used in Philips bedside monitors) on the American Heart Association (AHA) and MIT-BIH (Massachusetts Institute of Technology-Beth Israel Hospital) databases, and claimed that their algorithm achieved 100% sensitivity in generating red alarms during episodes of VF. GE Healthcare similarly claims that their bedside monitors demonstrated >95% sensitivity and >95% PPV in detecting VF episodes in the AHA and MIT-BIH databases. In the present study, our algorithm has also been able to generate a red alert for 100% of VF cases (83.8% as VF and 16.2% as VT). It is essential to note that an algorithm’s performance on such test databases do not necessarily reflect its performance in the real-world clinical settings. For example, GE Healthcare monitoring system achieved a PPV of >95% in identifying VF in the AHA and MIT-BIH databases, whereas it achieved a PPV of only 67.72% in identifying VF in the UCSF study.

In the previous subsection, we estimated that our method could raise ∼374 false alarms per patient, per day. Placing these results in context, Cho et al.’s study28 observed ∼697 false alarms per patient per day, Graham et al.’s study29 observed 942 alarms per patient per day, and The John Hopkins Hospital observed ∼350 alarms per patient per day.30 It should be noted that the conditions considered as alarm worthy differed from one study to another; furthermore, most studies have only mentioned the total count of alarms, but not the count of false alarms. Thus, while it is difficult to make an exact comparison between these studies, our method’s high PPV in life-threatening arrhythmias, provides superior false alarm reduction.

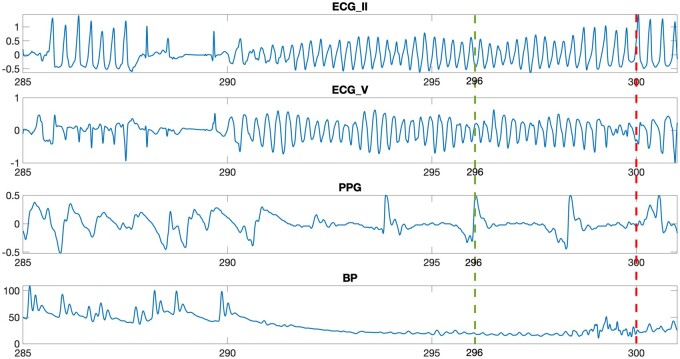

Algorithm efficiency performance

On a regular desktop with an Intel i5 processor, our proposed system took only few milliseconds to identify a given heart rhythm; the system is therefore realistic for real-world implementation and the heart rhythm classification may be evaluated/updated every sec. Moreover, our classification system captures arrhythmia-specific, vital-sign features that manifest themselves in differently sized windows. A sample recording from the PhysioNet 2015 Challenge that resulted in a VF alarm is presented in Figure 3; notably, our system was able to detect the presence of VF in this very sample more quickly—in fact 4 s faster—than the bedside monitors used in the challenge.

Figure 3.

The figure shows the plot of recording f563l between 285 and 301 s. The figure for this recording then compares the latency of bedside monitors and that of proposed system in alerting for ventricular fibrillation. The bedside monitor identifies the presence of ventricular fibrillation at 300th s, as visualized by the red dashed line. On the other hand, the proposed system can identify the presence of ventricular fibrillation at 296th s itself (4 s earlier), as visualized by the green line.

Discussion

Although monitors sound alarms when ICU patients experience abnormal heart rhythms, unfortunately, the majority of such alarms are found to be false.27 Excessive number of false alarms can create a noisy environment, and their effects on patients and families pertain to sleep disturbance, delirium, increased BP, and heart rate, negative effects on the immune system, slower healing and recovery process, increased length of stay, and impact on patient satisfaction.27,31 With respect to the effects on staff, noise increases occupational stress (irritation, fatigue, and tension headaches), reduces staff work performance and work satisfaction, delays recognition, and response to medical device alarm signals, which may negatively affect patient safety, and impairs oral communication and increases errors, which has a direct impact on patient safety.32,33 Too many false alarms can also lead to desensitization among caregivers, which could potentially cause them to mistakenly ignore true alarms as well. A growing number of research studies, some of which employ ML,3,4,34,35 have aimed to reduce the number of such false alarms, yet clearly better solutions are still needed. In this report, we present an arrhythmia alerting system that identified life-threatening arrhythmias more precisely and more efficiently than existing bedside monitors.

Several conclusions can be drawn from this study: first, obtaining arrhythmia-specific features from different length windows made the detection algorithm more efficient; second, our method can identify these arrhythmias with high sensitivity (a minimum of 83.8%); third, the RF classifier is not much affected by the class imbalance of the records; fourth, the algorithm does not have high computational requirements, therefore facilitating real-time implementation, and; fifth, the algorithm is at least as robust as those of several commercial bedside monitors.

Many prior heart rhythm classification studies11,12,14,17,18 have relied on analysing the ECG morphology only. This approach is limiting because arrhythmias, such as VT and VF, can be better detected with the inclusion of the BP signal. Even though all VT events may not be accompanied by haemodynamic instability, a fall in BP is expected w.r.t. to the baseline BP. Our heart rhythm classification algorithm utilizes the ECG, BP and PPG signals. Many heart rhythm classification studies that use ECG signals9,13 have not included VF as one of the arrhythmia classes detected. Our study not only included VF, but also alerted all cases of VF as life-threatening and did so 4 s faster than the bedside monitors used in PhysioNet 2015 challenge. Finally, some heart rhythm classification algorithms15 employ a short window of ECG segments to identify the arrhythmia and are therefore unable to identify rhythms that need a longer duration of ECG analysis, such as extreme bradycardia, whereas our algorithm is capable to detect such rhythms. By comparing the performance of our algorithm with those of the bedside monitors, one observes that the proposed algorithm achieves PPV for most life-threatening arrhythmias that are at least as high as the commercial monitors (Table 4).

Study limitations

In the present study, the sample size is small, especially for VF. Also, the ratios of the number of records among all these classes are not representative of real-life situations, e.g. even though a large number of NSRs have been included during training and testing, in reality the ratio of NSR occurrences to the number of other heart rhythm occurrences, is expected to be even more skewed, which may affect performance metrics. We believe a larger scale study on real-world ICU patient data would be very informative and enable us to refine our algorithms further.

Conclusions

We have built a standalone algorithm that can successfully utilize live-streaming data in the ICU to successfully identify multiple life-threatening arrhythmias in real time, and may be of significant clinical benefit. False alarms could be further reduced, by wrapping the proposed method with false alarm detection mechanisms22,35; however, it should be noted that false alarm detection mechanisms are generally built over small data sets,2 and methods built for one type of monitor may not work well for another. In our study, we designed features that measured the signal quality of ECG, BP, and PPG, and designed arrhythmia-specific features to identify the presence of a particular characteristic and/or morphology. The engineered features provided a reasonably good classification performance. Moving forward, we would like to explore augmenting the proposed system with features derived from deep learning architectures, in order to improve classification performance and clinical utility.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Digital Health online.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

We used data from the ‘PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2015: Reducing False Arrhythmia Alarms in the ICU’. The data used are open source and are available at https://physionet.org/content/challenge-2015/1.0.0/ (28 June 2021).

Funding

The work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid (#15GRNT23070001) from the American Heart Association (AHA), the Institute of Precision Medicine (17UNPG33840017) from the AHA, the RICBAC Foundation, National Institutes of Health grants 1 R01 HL135335-01, 1 R21 HL137870-01, and 1 R21 EB026164-01, and a Founders Affiliate Post-doctoral Fellowship (#19POST34450149) from the AHA.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no competing interests, financial and non-financial interests of any kind.

Data availability

The data will be available to any investigator upon request.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Cvach M. Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomed Instrum Technol 2012;46:268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clifford GD, Silva I, Moody B, Li Q, Kella D, Shahin A, Kooistra T, Perry D, Mark RG.. The PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2015: reducing false arrhythmia alarms in the ICU. Comput Cardiol (2010) 2015;2015:273–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plesinger F, Klimes P, Halamek J, Jurak P.. Taming of the monitors: reducing false alarms in intensive care units. Physiol Meas 2016;37:1313–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kalidas V, Tamil LS.. Cardiac arrhythmia classification using multi-modal signal analysis. Physiol Meas 2016;37:1253–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eerikainen LM, Vanschoren J, Rooijakkers MJ, Vullings R, Aarts RM.. Reduction of false arrhythmia alarms using signal selection and machine learning. Physiol Meas 2016;37:1204–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eerikäinen LM, Vanschoren J, Rooijakkers MJ, Vullings R, Aarts RM.. 2015 Computing in Cardiology Conference (CinC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p293–296. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sevakula RK, Au-Yeung WM, Singh JP, Heist EK, Isselbacher EM, Armoundas AA.. State‐of‐the‐art machine learning techniques aiming to improve patient outcomes pertaining to the cardiovascular system. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e013924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bazoukis G, Stavrakis S, Zhou J, Bollepalli SC, Tse G, Zhang Q, Singh JP, Armoundas AA.. Machine learning versus conventional clinical methods in guiding management of heart failure patients—a systematic review. Heart Fail Rev 2021;26:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guvenir HA, Acar B, Demiroz G, Cekin A.. Computers in Cardiology. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 1997. p433–436. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dua D, Graff C.. UCI Machine Learning Repository. Irvine, CA: University of California, School of Information and Computer Science 2017. http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml (28 June 2021).

- 11. Jadhav SM, Nalbalwar SL, Ghatol AA.. Modular neural network based arrhythmia classification system using ECG signal data. Int J Inf Technol Knowledge Manage 2011;4:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jadhav SM, Nalbalwar S, Ghatol A.. 2010 International Conference on Electronics and Information Engineering. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. pV1-228–V221-231.

- 13.Liu F, Liu C, Zhao L, Zhang X, Wu X, Xu X, Liu Y, Ma C, Wei S, He Z, Li J, Yin K, Ng E. An open access database for evaluating the algorithms of electrocardiogram rhythm and morphology abnormality detection. J Med Imaging Health Inf 2018;8:1368–1373. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen T-M, Huang C-H, Shih ES, Hu Y-F, Hwang M-J.. Detection and classification of cardiac arrhythmias by a challenge-best deep learning neural network model. Iscience 2020;23:100886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannun AY, Rajpurkar P, Haghpanahi M, Tison GH, Bourn C , Turakhia MP, Ng AY. .Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Nat Med 2019;25:65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kampouraki A, Manis G, Nikou C.. Heartbeat time series classification with support vector machines. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed 2008;13:512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman QA, Tereshchenko LG, Kongkatong M, Abraham T, Abraham MR, Shatkay H. et al. Utilizing ECG-based heartbeat classification for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy identification. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci 2015;14:505–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luz EJdS, Schwartz WR, Cámara-Chávez G, Menotti D.. ECG-based heartbeat classification for arrhythmia detection: a survey. Comput Methods Prog Biomed 2016;127:144–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clifford GD, Liu C, Moody B, Lehman LH, Silva I, Li Q, Johnson AE, Mark RG. 2017 Computing in Cardiology (CinC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. Teijeiro T, García CA, Castro D, Félix P.. Arrhythmia classification from the abductive interpretation of short single-lead ECG records. Comput Cardiol 2017;44:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Plesinger F, Nejedly P, Viscor I, Halamek J, Jurak P.. Parallel use of a convolutional neural network and bagged tree ensemble for the classification of Holter ECG. Physiol Meas 2018;39:094002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Au-Yeung WTM, Sahani AK, Isselbacher EM, Armoundas AA.. Reduction of false alarms in the intensive care unit using an optimized machine learning based approach. NPJ Digit Med 2019;2:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martinez JP, Almeida R, Olmos S, Rocha AP, Laguna P.. A wavelet-based ECG delineator: evaluation on standard databases. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2004;51:570–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vistisen ST, Johnson, AEW, Scheeren TWL. Predicting vital sign deterioration with artificial intelligence or machine learning. J Clin Monit Comput 2019;33:949–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen C, Liaw A, Breiman L.. Using Random Forest to Learn Imbalanced Data, Vol. 110. Berkeley: University of California; 2004. p24.

- 26. Aboukhalil A, Nielsen L, Saeed M, Mark RG, Clifford GD.. Reducing false alarm rates for critical arrhythmias using the arterial blood pressure waveform. J Biomed Inform 2008;41:442–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drew BJ, Harris P, Zègre-Hemsey JK, Mammone T, Schindler D, Salas-Boni R, Bai Y, Tinoco A, Ding Q, Hu X. . Insights into the problem of alarm fatigue with physiologic monitor devices: a comprehensive observational study of consecutive intensive care unit patients. PLoS One 2014;9:e110274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cho OM, Kim H, Lee YW, Cho I.. Clinical alarms in intensive care units: Perceived obstacles of alarm management and alarm fatigue in nurses. Healthcare Inform Res 2016;22:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Graham KC, Cvach M.. Monitor alarm fatigue: standardizing use of physiological monitors and decreasing nuisance alarms. Am J Crit Care 2010;19:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sendelbach S, Funk M.. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care 2013;24:378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lawless ST. Crying wolf: false alarms in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1994;22:981–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilken M, Hüske-Kraus D, Klausen A, Koch C, Schlauch W, Röhrig R. Alarm fatigue: causes and effects. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017; 243:107–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Donchin Y, Seagull F J.. The hostile environment of the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care 2002;8:316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eerikäinen LM, Vanschoren J, Rooijakkers MJ, Vullings R, Aarts RM.. Reduction of false arrhythmia alarms using signal selection and machine learning. Physiol Meas 2016;37:1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fernandes CO, Miles S, De Lucena CJP, Cowan D.. Artificial intelligence technologies for coping with alarm fatigue in hospital environments because of sensory overload: algorithm development and validation. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e15406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available to any investigator upon request.