This cohort study investigates the association of delayed surgery with oncologic long-term outcomes in patients with nonresponsive locally advanced rectal cancer.

Key Points

Question

Is delayed surgery associated with long-term survival outcomes in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who do not respond to neoadjuvant treatment?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1064 patients, a longer interval before surgery after completing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy was associated with worse survival in patients with tumors with a poor pathological response to preoperative chemoradiation.

Meaning

Based on these findings, patients who do not respond well to chemoradiotherapy should be identified early after the end of chemoradiation and undergo surgery without delay.

Abstract

Importance

Extending the interval between the end of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and surgery may enhance tumor response in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. However, data on the association of delaying surgery with long-term outcome in patients who had a minor or poor response are lacking.

Objective

To assess a large series of patients who had minor or no tumor response to CRT and the association of shorter or longer waiting times between CRT and surgery with short- and long-term outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Data from 1701 consecutive patients with rectal cancer treated in 12 Italian referral centers were analyzed for colorectal surgery between January 2000 and December 2014. Patients with a minor or null tumor response (ypT stage of 2 to 3 or ypN positive) stage greater than 0 to neoadjuvant CRT were selected for the study. The data were analyzed between March and July 2020.

Exposures

Patients who had a minor or null tumor response were divided into 2 groups according to the wait time between neoadjuvant therapy end and surgery. Differences in surgical and oncological outcomes between these 2 groups were explored.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were overall and disease-free survival between the 2 groups.

Results

Of a total of 1064 patients, 654 (61.5%) were male, and the median (IQR) age was 64 (55-71) years. A total of 579 patients (54.4%) had a shorter wait time (8 weeks or less) 485 patients (45.6%) had a longer wait time (greater than 8 weeks). A longer waiting time before surgery was associated with worse 5- and 10-year overall survival rates (67.6% [95% CI, 63.1%-71.7%] vs 80.3% [95% CI, 76.5%-83.6%] at 5 years; 40.1% [95% CI, 33.5%-46.5%] vs 57.8% [95% CI, 52.1%-63.0%] at 10 years; P < .001). Also, delayed surgery was associated with worse 5- and 10-year disease-free survival (59.6% [95% CI, 54.9%-63.9%] vs 72.0% [95% CI, 67.9%-75.7%] at 5 years; 36.2% [95% CI, 29.9%-42.4%] vs 53.9% [95% CI, 48.5%-59.1%] at 10 years; P < .001). At multivariate analysis, a longer waiting time was associated with an augmented risk of death (hazard ratio, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.50-2.26; P < .001) and death/recurrence (hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.39-2.04; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, a longer interval before surgery after completing neoadjuvant CRT was associated with worse overall and disease-free survival in tumors with a poor pathological response to preoperative CRT. Based on these findings, patients who do not respond well to CRT should be identified early after the end of CRT and undergo surgery without delay.

Introduction

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) is the standard approach for locally advanced rectal cancer, resulting in better locoregional control and disease-free survival (DFS).1,2 TME consists of an excision of the rectum with the surrounding fat tissue containing lymph nodes. Dissection is achieved along an avascular plane between the presacral and mesorectal fascia.3

Notable differences among patients in treatment response to CRT exist. Approximately 15% to 20% of patients receiving neoadjuvant radiotherapy achieve a pathologic complete response (pCR) that has been associated with lower chances of local recurrence, and better overall and DFS compared with minimal or no pathologic response.4 Tumor complete response has become of even greater clinical interest following evidence that, beyond oncological outcomes, it might also avoid radical surgery and preserve the rectum.5,6,7,8,9,10 For these reasons, pCR after CRT is one of the major end points in current clinical practice.

Different studies have demonstrated a direct association between a longer wait time before surgery and pCR rates.9,10 To our knowledge, the Lyon R90-01 trial5 was the first to find that cancer response to radiation therapy improved in patients undergoing surgery up to 6 to 8 weeks after treatment compared with those undergoing surgery within a 2-week interval. The proposed optimal interval between CRT and surgery has further increased over the years. Nowadays, waiting up to 12 weeks before proceeding to surgical resection has become a widely accepted practice, based on evidence that tumor response may achieve its maximum by then.11,12 From the side of those patients who eventually experience a complete or at least a good response, the benefits related to this practice appear clear. On the other hand, a large percentage of patients will not ultimately reach a meaningful regression in tumor size (downsizing) or stage (downstaging). In this group, the final association of delaying surgical resection with early-term and long-term outcomes is unknown.

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to assess the association of shorter or longer wait times between CRT and surgery with short- and long-term outcomes in a large series of patients who had minor or no tumor response.

Methods

Data of patients who underwent CRT and surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer (clinical stage of II-III) between January 2000 and December 2014 in 12 Italian high-volume referral centers for colorectal surgery were identified. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The period was chosen to include patients with a minimum follow-up time of 5 years. Clinical and follow-up data were extracted from proprietary electronical databases prospectively maintained in each participating center.

A total of 1701 patients who had undergone surgical resection for locally advanced rectal cancer were selected for the study. For 11 patients, the interval between CRT and surgery was not available, while 223 patients had unavailable or incomplete clinical data. Sixteen patients were excluded because they had a local excision despite suboptimal tumor response, and 387 were excluded because they achieved a complete or major pathologic response (ypT stage of 0 to 1 and ypN stage of 0).

Clinical staging included at least digital rectal examination, colonoscopy, and abdominal computed tomography scan. From 2007, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging was routinely used to assess local stage. Patient demographics characteristics and available clinical and therapeutic data were collected in an electronic database.

Patients were older than 18 years, with histologically proven rectal adenocarcinoma in pretreatment stages II and III, and underwent long-course CRT with subsequent TME. All procedures were done by senior surgeons from each center. The completeness of TME was certified by the surgeon or by the pathologist, depending on center practice. All patients had a complete TME. Patients with pretreatment stage IV rectal cancer, concomitant inflammatory bowel disease, or familial polyposis and those who underwent an emergency procedure were excluded from the study.

The standard CRT schedule consisted of long-course radiotherapy with at least a dose of 45 Gy administered over 5 weeks (25 fractions of 1.8 Gy per day) with a 3-field technique. In most patients, a tumor boost of 9 Gy for a total dose of 54 Gy was used. Preoperative CRT consisted of 5-fluorouracil (FU) administered either in a daily oral preparation (capecitabine, 1650 mg/m2, daily) taken during the radiation period or in bolus infusion (5-FU, 325 mg/m2/, daily) for 5 days during weeks 1 and 5 or as continuous infusion for 5 days per week over the entire radiation period (5-FU, 250 mg/m2, daily). After surgery, all patients were included in follow-up programs. Follow-up schedules varied among participating centers but included at least a clinical examination every 6 months until the fifth year and annually thereafter; routine carcinoembryonic antigen monitoring at every visit; sigmoidoscopy for the first 3 years and colonoscopy after the first year and after 5 years if negative; and abdominal, pelvic, and chest computed tomography scans every 6 months for the first 3 years and then yearly until the fifth year; thereafter, computed tomography scan was based on physician indication. Tumor response was defined as the difference between pretreatment clinical and pathological stage after surgical resection (ypTNM).13 Response was deemed as good if ypT stage was 0 to 1 and ypN stage was 0. For the aim of the study, we identified patients with partial or no response at final pathology, defined as a final ypT stage of 2 to 4 or ypN stage greater than 0. These patients are known to constitute a subgroup with worst survival probability.4,14,15

This cohort of patients was divided into 2 groups based on the time interval between the end of CRT and surgery: those with an interval of 8 weeks or less (shorter interval group) and those with an interval greater than 8 weeks (longer interval group). The optimal interval time between CRT and surgery has yet to be fully defined. The cutoff was chosen for different reasons. Available literature indicates that a waiting period of at least 8 weeks is necessary to optimize treatment effects and to increase the rate of responders.6 This lower limit is nowadays widely used in clinical practice. This cutoff was also the median waiting time in our population.

The collected variables were analyzed for significant differences between the 2 groups. Categorical variables were analyzed with Fisher exact test with mid-P correction or χ2 test, whereas continuous variables were tested by Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Continuous values are expressed as median with 25th to 75th percentile IQRs.

Survival probabilities and cumulative rates were assessed by Kaplan-Meier estimate method. Differences between the groups were assessed by log-rank test.

Cox proportional hazard regression models were used for multivariate survival analysis, adjusting for factors known to be associated with survival outcomes. Sex, age, and distance of the tumor from anal verge were included as continuous variables, while preoperative T and N stage, circumferential resection margin status, postoperative complications, and adjuvant treatment history were included as categorical. All multivariate analyses were stratified by center. Hazard ratios are reported with 95% CIs. The proportional hazards assumption was satisfied by the Schoenfeld residual method.

Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time between surgical resection and death from any cause; DFS was defined as the time between surgical resection and local or distant recurrence or death, whichever came first. All survival analyses were censored at last follow-up date. Analysis was performed using available observations on all participants who entered the study.

Data were analyzed from March to July 2020. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp).

Results

The analysis included 1064 patients who had a partial or no pathological response to CRT: 579 (54.4%) in the shorter interval group who received CRT within 8 weeks and 485 (45.6%) in the longer interval group who received treatment after 8 weeks (eFigure in the Supplement). There were 654 men (61.5%) and 410 women (38.5%), with a median (IQR) age of 64 (55-71) years. Data on race and ethnicity were not collected.

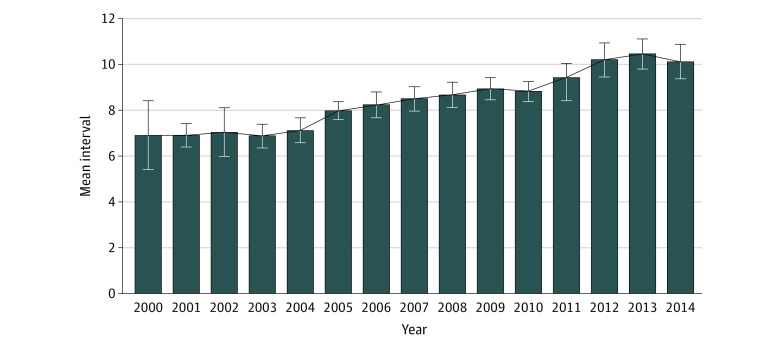

The median (IQR) waiting time was 7 (6-8) weeks for the shorter interval group and 10.6 (9-12.3) weeks for the longer interval group. During the study period, the interval time between the end of CRT and surgical resection increased in the entire population (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mean Wait Period Between Chemoradiotherapy and Surgical Resection Between 2000 and 2014 Among Patients With Nonresponsive Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer.

The wait period between the end of chemoradiotherapy and surgical resection increased from 2000 to 2014. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The 2 groups were homogeneous for all demographic and pretreatment characteristics. Pretreatment schedule (radiation therapy doses) and adjuvant therapy rates were also comparable between the groups.

Table 1. Patient and Treatment Details.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1064) | Wait time | |||

| ≤8 wk (n = 579) | >8 wk (n = 485) | |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 64 (55-71) | 63 (54-70) | 65 (57-71) | .99 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 654 (61.5) | 359 (62.0) | 295 (60.8) | .72 |

| Female | 410 (38.5) | 220 (38.0) | 190 (39.2) | |

| CEA, median (IQR), ng/mL | 3.3 (1.7-7.9) | 3 (1.5-7.1) | 3.3 (1.8-8.4) | .18 |

| Distance from the anal verge, median (IQR), cm | 6 (4-8) | 7 (5-8) | 6 (4-8) | .06 |

| cT stage | ||||

| 2 | 76 (7.2) | 45 (7.8) | 31 (6.4) | .61 |

| 3 | 893 (84.1) | 486 (83.9) | 407 (84.3) | |

| 4 | 93 (8.8) | 48 (8.3) | 45 (9.3) | |

| cN stage | ||||

| 0 | 346 (32.5) | 179 (30.9) | 167 (34.4) | .22 |

| 1 | 718 (67.5) | 400 (69.1) | 318 (65.6) | |

| Radiotherapy, Gy | ||||

| 54 | 953 (89.6) | 512 (88.4) | 441 (90.9) | .18 |

| 45 | 111 (10.4) | 67 (11.6) | 44 (9.1) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 138 (13) | 74 (12.8) | 64 (13.2) | .84 |

| Yes | 926 (87) | 505 (87.2) | 421 (86.8) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 390 (36.6) | 205 (35.4) | 185 (38.1) | .36 |

| Yes | 674 (63.3) | 374 (64.6) | 300 (61.9) | |

| Surgical procedures | ||||

| Anterior resection | 770 (72.3) | 449 (77.5) | 321 (66.2) | <.001 |

| Abdominoperineal resection | 288 (27.1) | 127 (21.9) | 161 (33.2) | |

| Hartmann resection | 6 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.6) | |

| 30-d Morbidity | ||||

| Yes | 181 (17.1) | 86 (14.8) | 95 (19.6) | .04 |

| No | 883 (82.9) | 493 (85.2) | 390 (80.4) | |

| Medical complications | ||||

| Yes | 44 (4.1) | 23 (4.0) | 21 (4.3) | .77 |

| No | 1020 (95.9) | 556 (96.0) | 464 (95.7) | |

| Surgical complications | ||||

| Yes | 131 (12.3) | 58 (10.0) | 73 (15.1) | .01 |

| No | 933 (87.7) | 521 (90.0) | 412 (84.9) | |

| Anastomotic leakage | ||||

| Yes | 87 (8.2) | 39 (6.7) | 48 (9.9) | .06 |

| No | 977 (91.8) | 540 (93.2) | 437 (90.1) | |

| Wound infections | ||||

| Yes | 36 (3.4) | 20 (3.4) | 16 (3.3) | .88 |

| No | 1028 (96.6) | 559 (96.5) | 469 (96.7) | |

| Hemorrhage | ||||

| Yes | 10 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | 5 (1.0) | .77 |

| No | 1054 (99.1) | 574 (99.1) | 480 (98.9) | |

| Ileus | ||||

| Yes | 10 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (1.9) | .01 |

| No | 1054 (99.1) | 578 (99.8) | 476 (98.1) | |

| 30-d Mortality | ||||

| Yes | 6 (0.6) | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | .54 |

| No | 1058 (99.4) | 576 (99.3) | 482 (99.6) | |

| ypT stage | ||||

| 0 | 9 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) | 7 (1.5) | .03 |

| 1 | 12 (1.1) | 10 (1.7) | 2 (0.4) | |

| 2 | 375 (35.2) | 192 (33.1) | 183 (37.8) | |

| 3 | 619 (58.2) | 347 (59.8) | 272 (56.2) | |

| 4 | 49 (4.6) | 29 (5.0) | 20 (4.1) | |

| ypN stage | ||||

| 0 | 677 (63.6) | 342 (59.0) | 335 (69.2) | .02 |

| 1 | 271 (25.5) | 170 (29.3) | 101 (20.9) | |

| 2 | 116 (10.9) | 68 (11.7) | 48 (9.9) | |

| CRM | ||||

| Positive | 12 (1.3) | 3 (0.5) | 9 (1.9) | .04 |

| Negative | 1052 (98.9) | 576 (99.5) | 476 (98.1) | |

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRM, circumferential resection margin; CM, centimeter.

SI conversion factor: To convert CEA to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.

A wait time greater than 8 weeks was associated with significantly higher rates of abdominal perineal resections (161 of 485 [33.2%] vs 127 of 579 [21.9%]; odds ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2; P < .001), positive circumferential resection margin (9 of 485 [1.7%] vs 3 of 579 [0.5%]; odds ratio, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.1-12.4; P = .04), 30-day morbidity rates (95 of 485 [19.6%] vs 86 of 579 [14.8%]; odds ratio, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-1.9; P = .04), and surgical complication rates (73 of 485 [15.1%] vs 58 of 579 [10.0%] odds ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1-2.3; P = .01). Anastomotic leakage rate was also nonsignificantly higher in the longer interval group (Table 1).

At a median (IQR) follow-up of 63 (38-95) months, 286 patients (26.9%) had a recurrence and 400 (37.7%) died during the study period; 80 (7.5%) had a local recurrence, 254 (23.9%) had a distant recurrence, and 48 (4.5%) had both local and distant recurrences.

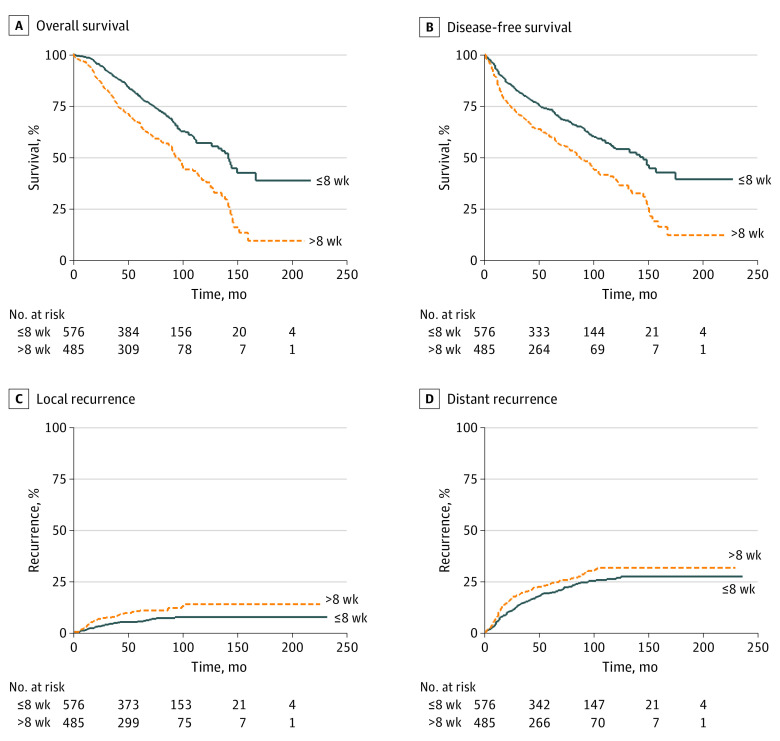

Remarkably, a longer waiting period (longer interval group) was associated with worse long-term outcomes, both in terms of OS (67.6% [95% CI, 63.1%-71.7%] vs 80.3% [95% CI, 76.5%-83.6%] at 5 years, 40.1% [95% CI, 33.5%-46.5%] vs 57.8% [95% CI, 52.1%-63.0%] at 10 years; P < .001; (Figure 2A) and DFS (59.6% [95% CI, 54.9%-63.9%] vs 72.0% [95% CI, 67.9%-75.7%] at 5 years, 36.2% [95% CI, 29.9%-42.4%] vs 53.9% [95% CI, 48.5%-59.1%] at 10 years; P < .001); Figure 2B). A longer interval was also correlated with a significantly higher cumulative incidence of local recurrence (10.4% [95% CI, 7.8%-13.7%] vs 5.3% [95% CI, 3.7%-7.7%] at 5 years and 13.4% [95% CI, 9.8%-18.2%] vs 7.1% [95% CI, 5.0%-10.2%] at 10 years; P = .005; Figure 2C) and distant recurrence (25.5% [95% CI, 21.6%-29.9%] vs 20.8% [95% CI, 17.5%-24.6%] at 5 years; 32.9% [95% CI, 27.9%-38.5%] vs 28.4% [95% CI, 24.1%-33.3%] at 10 years; P = .055; Figure 2D). Also, our data showed that patients who had surgery after 8 weeks had a linear worsening of survival for each additional month of waiting (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Survival and Recurrence Among Patients With Nonresponsive Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival (A) and disease-free survival (B) as well as cumulative incidence curves of local recurrence (C) and distance recurrence (D) in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated by neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and total mesorectal excision and stratified according to a short (shorter interval group; 8 weeks or less) or long (longer interval group; greater than 8 weeks) interval.

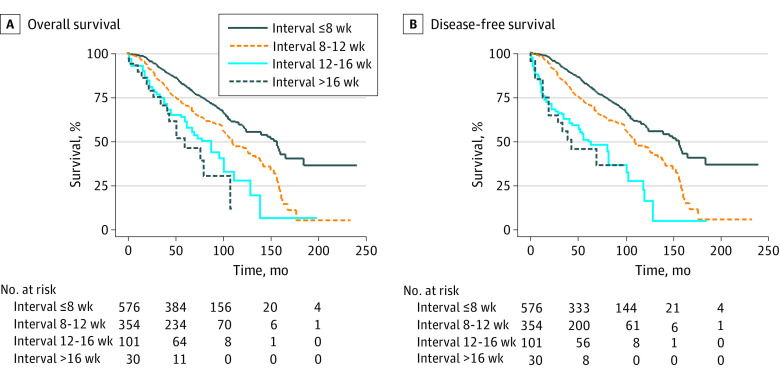

Figure 3. Survival Curve of Patients Stratified for Every Additional Month of Waiting After 8 Weeks.

Overall survival (A) and disease-free survival (B) (Kaplan-Meier estimates) in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated by neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and total mesorectal excision, stratified for every month of waiting after 8 weeks.

The association between delayed surgery and long-term outcome was confirmed by Cox analysis (Table 2); a longer wait time was independently associated with a higher risk of death (hazard ratio, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.50-2.26; P < .001) and death/recurrence (hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.39-2.04; P < .001).

Table 2. Multivariate Analysis for Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DSF)a.

| Characteristic | OS | DFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | <.001 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .01 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Male | 1.13 (0.89-1.43) | .31 | 1.10 (0.88-1.35) | .42 |

| Interval, wk | ||||

| ≤8 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| >8 | 1.84 (1.50-2.26) | <.001 | 1.69 (1.39-2.04) | <.001 |

| ypT stage | ||||

| 0-1 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 2 | 1.13 (0.48-2.66) | .77 | 1.10 (0.48-2.33) | .82 |

| 3 | 1.71 (0.75-3.95) | .20 | 1.62 (0.75-3.48) | .22 |

| 4 | 2.32 (0.94-5.75) | .07 | 2.31 (0.99-5.36) | .05 |

| ypN stage | ||||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1 | 1.65 (1.26-2.15) | <.001 | 1.42 (1.11-1.83) | .01 |

| 2 | 3.51 (2.53-4.88) | <.001 | 2.90 (2.13-3.93) | <.001 |

| CRM | ||||

| Negative | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Positive | 0.92 (0.43-1.98) | .84 | 1.35 (0.70-2.60) | .41 |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 0.55 (0.43-0.69) | <.001 | 0.59 (0.47-0.74) | < .001 |

| Postoperative complications | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 1.40 (1.10-1.78) | .001 | 1.35 (1.07-169) | .01 |

Abbreviations: CRM, circumferential resection margin; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable.

Stratified by centers.

Other factors that were found to be independently associated with OS and DFS were age, ypN stages, and postoperative complications. Interestingly, adjuvant chemotherapy was also independently associated with better survival in these patients. In this regard, 390 patients (36.6%) in the entire population did not have an adjuvant treatment. Compared with 674 patients (63.3%) who proceeded to postoperative chemotherapy, those who did not have an adjuvant treatment were older (median [IQR] age, 65 [57-71] years [95% CI, 62.3-64.5 vs 63 [54-70] years [95% CI, 60.7-62.5]; P = .01), had mostly a final pathologic stage less than III (375 of 390 [91.5%] vs 320 of 674 [47.5%]; odds ratio, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.05-0.11; P < .001), and had a higher rate of postoperative complications (82 of 390 [21.0%] vs 99 of 674 [14.7%]; odds ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.46-0.89; P = .01) and a higher rate of anastomotic leakage (43 of 390 [11.0%] vs 44 of 674 [6.5%]; odds ratio, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39-0.87; P = .01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first that specifically explores whether delaying surgery after CRT could be a risk factor of worse outcome in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer and suboptimal or no tumor response after neoadjuvant radiotherapy. The main finding of the present study is that delaying surgery after CRT is associated with reduced OS and DFS rates in these patients.

Studies addressing the association of different wait times after neoadjuvant treatment with rectal cancer outcomes have indeed focused mainly on tumor response.16,17,18 Prolonging the interval up to 12 weeks and beyond has consistently been associated with trends toward higher rates of pCR.6 It is well known that achieving a pCR is associated with survival advantages.4,19 Adding to the mounting evidence that these patients might be suitable for an organ-preserving strategy and avoid radical surgery,14,20 the step toward delaying surgical resection might seem a good option. This evolution was confirmed by our data from 12 Italian referral centers in which the interval to surgery has steadily and progressively increased over the years from a median of 6 to 7 weeks in the early years of the 2000s to more than 11 to 12 weeks, an increment of more than 1 month, at the end of the study period in 2014.

Our study shows that extending this time in the search for more pathologic responses occurs at the expense of a worse outcome in most patients (almost 75% in our series) who will not achieve the desired pathologic response. The magnitude of the detrimental effect of delaying surgical resection in these patients, in terms of OS, that is shown in our study is clinically relevant (reaching almost a 20% difference at 10 years) and somehow unexpected.

These are unlikely to be overestimations. As rectal cancer prognosis improved over the last 20 years, and in this study, the use of a longer interval before surgery appeared to increase in more recent years, one would have expected a better rather than worse outcome for patients in the prolonged interval group.

Previous studies dealing with the role of the wait period before surgery mostly reported a negligible effect on survival. A 2019 meta-analysis that included 4 randomized clinical trials has supported a minimum 8-week interval from the end of CRT to surgery as the standard of care, whereas longer intervals did not appear to negatively influence OS.21

However, most of the published studies focused on early outcomes and lack the power to assess the long-term oncologic effects because of low number of patients or events and short follow-up periods. Other studies in which long-term outcomes have been specifically explored included all pathological stages of rectal cancers. In these studies, the favorable long-term outcome of the group of patients achieving a major pathologic response might have masked or mitigated the detrimental effect occurring in patients with a poor response to neoadjuvant CRT.

For this reason, previous data may be largely biased and, in any case, not comparable with our study. In tumors that respond well to preoperative chemoradiation, surgeons may be more confident with waiting much longer in case a clinical response has been achieved, thus inflating the longer interval group with cancers with a favorable biological behavior. As an example, in the 3-year results of the GRECCAR-6 study,22 delaying the interval between CRT and surgery for more than 11 weeks vs 7 weeks did not influence the 3-year OS or DFS. However, 20.8% of patients in the 7-week group ultimately underwent surgery after the specified time and mostly in the 10-week range.23 Interestingly, in a brief commentary, the authors acknowledge that when calculating actual local recurrence rate at 2 years, they found significantly more local recurrences in the longer interval group.22

As shown in Figure 3, from a secondary analysis of our data, we found a linear association toward worse survival for every additional month of waiting. Interestingly, this association was similar to what was reported in a 2019 study from more than 500 000 patients with colon cancer from the US National Cancer Database, where authors found a linear association between prolonged time to surgery (in 1-month intervals) and increased mortality.24

Another point against waiting longer for this subgroup is that it may also negatively influence early surgical outcomes. These data have already been observed in the GRECCAR-6 trial23 in which overall morbidity was higher in the late surgery group. The authors have suggested that pelvic fibrosis may increase over time after CRT. This process would lead to a more difficult surgery, especially if performed laparoscopically, and might explain the significant higher rate of abdominoperineal resections (33.2% vs 21.9%) linked to the late surgery group in our study despite the similar median distance from anal verge in both groups.

The potential biases are largely compensated by the strength of numbers. Our study has a very large sample size together with a mature follow-up. Moreover, data were obtained from prospectively maintained data sets from referral colorectal cancer centers. The reliability of the included databases is shown from the relatively low rate of missing or incomplete data (223 among more than 1700 cases [13%]). The surgical quality by the overall low rate of positive circumferential resection margin and by the shown comparability among centers.

A main focus in cancer research is probably how to fit treatment to each patient and each single tumor. In rectal cancer, this issue is clearly a main topic of interest that is made very complex by the increasingly complexity of multidisciplinary therapeutic options. Our data have also shown that adjuvant chemotherapy in these tumors with bad prognosis emerged associated with better outcomes. In this regard, these patients might benefit from more aggressive neoadjuvant treatment strategies by shifting chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant period.16,25 This specific topic is surely of interest and will be better addressed in a further prospective study from the collaborative multicenter group.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. The main bias is because of the retrospective design. As with every retrospective series, bias owing to patient selection and heterogeneity of clinical practice and, in particular, of follow-up may exist. This is at least partially exceeded by the fact that every center had a follow-up schedule that included a minimum of criteria as listed in the Methods. Another bias may result from the absence of a systematic prospective assessment of TME quality.

Conclusions

In conclusion, these data have important clinical implications. Our findings challenge the overuse of pCR as the main end point to drive therapeutic strategies. Strategies useful to push up response rates may indeed result in an (unproven) benefit in responding patients but at the price of a detrimental effect for those not responding. This may be particularly true when the enhanced response is artificially obtained with a delay of assessment time.

Ideally, we should be able to select patients up-front. Unfortunately, this kind of fine selection is still not available or at least not tuned. Patient selection in current clinical practice is mainly based on preoperative TNM stage that, as shown also in our data, has clear limitation. While trying to overcome these limits, we believe patients with a poor response to neoadjuvant treatment should be reevaluated and selected early by using available staging modalities, such as endoscopy and magnetic resonance imaging.26,27 In case a clear clinical response is not seen within a specific time period (at least before 8 weeks), rectal resection should not be delayed. The reported evidence suggests an immediate revision of current practice.

eFigure. CONSORT Diagram.

References

- 1.Ceelen W, Fierens K, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Pattyn P. Preoperative chemoradiation versus radiation alone for stage II and III resectable rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(12):2966-72. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CAM, Nagtegaal ID, et al. ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group . Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):638-646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heald RJ, Ryall RDH. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1(8496):1479-1482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91510-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zorcolo L, Rosman AS, Restivo A, et al. Complete pathologic response after combined modality treatment for rectal cancer and long-term survival: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2822-2832. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2209-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francois Y, Nemoz CJ, Baulieux J, et al. Influence of the interval between preoperative radiation therapy and surgery on downstaging and on the rate of sphincter-sparing surgery for rectal cancer: the Lyon R90-01 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalady MF, de Campos-Lobato LF, Stocchi L, et al. Predictive factors of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;250(4):582-589. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b91e63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore HG, Gittleman AE, Minsky BD, et al. Rate of pathologic complete response with increased interval between preoperative combined modality therapy and rectal cancer resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(3):279-286. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0062-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tulchinsky H, Shmueli E, Figer A, Klausner JM, Rabau M. An interval >7 weeks between neoadjuvant therapy and surgery improves pathologic complete response and disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(10):2661-2667. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9892-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gambacorta MA, Masciocchi C, Chiloiro G, et al. Timing to achieve the highest rate of pCR after preoperative radiochemotherapy in rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 3085 patients from 7 randomized trials. Radiother Oncol. 2021;154:154-160. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Campos-Lobato LF, Geisler DP, da Luz Moreira A, Stocchi L, Dietz D, Kalady MF. Neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: the impact of longer interval between chemoradiation and surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(3):444-450. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1197-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hupkens BJP, Maas M, Martens MH, et al. Organ preservation in rectal cancer after chemoradiation: should we extend the observation period in patients with a clinical near-complete response? Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(1):197-203. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6213-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Probst CP, Becerra AZ, Aquina CT, et al. ; Consortium for Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRiCh) . Extended intervals after neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: the key to improved tumor response and potential organ preservation. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(2):430-440. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edge SB, Compton CC. The 7th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and the Future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010; 17(6):1471-4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barina A, De Paoli A, Delrio P, et al. Rectal sparing approach after preoperative radio- and/or chemotherapy (RESARCH) in patients with rectal cancer: a multicentre observational study. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(8):633-640. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1665-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng Y, Chi P, Lan P, et al. Neoadjuvant modified FOLFOX6 with or without radiation versus fluorouracil plus radiation for locally advanced rectal cancer: final results of the Chinese FOWARC Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(34):3223-3233. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Aguilar J, Smith DD, Avila K, Bergsland EK, Chu P, Krieg RM; Timing of Rectal Cancer Response to Chemoradiation Consortium . Optimal timing of surgery after chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer: preliminary results of a multicenter, nonrandomized phase II prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2011;254(1):97-102. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182196e1f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sloothaak DA, Geijsen DE, van Leersum NJ, et al. ; Dutch Surgical Colorectal Audit . Optimal time interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(7):933-939. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolthuis AM, Penninckx F, Haustermans K, et al. Impact of interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and TME for locally advanced rectal cancer on pathologic response and oncologic outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2833-2841. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2327-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan BM, Lefort F, McManus R, et al. A prospective study of circulating mutant KRAS2 in the serum of patients with colorectal neoplasia: strong prognostic indicator in postoperative follow up. Gut. 2003;52(1):101-108. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capelli G, De Simone I, Spolverato G, et al. Non-operative management versus total mesorectal excision for locally advanced rectal cancer with clinical complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: a GRADE approach by the rectal cancer guidelines writing group of the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM). J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(9):2150-2159. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04635-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan ÉJ, O’Sullivan DP, Kelly ME, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of extending the interval after long-course chemoradiotherapy before surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2019;106(10):1298-1310. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefèvre JH, Mineur L, Cachanado M, et al. ; The French Research Group of Rectal Cancer Surgery (GRECCAR) . Does a longer waiting period after neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy improve the oncological prognosis of rectal cancer?: three years’ follow-up results of the Greccar-6 randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270(5):747-754. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefevre JH, Mineur L, Kotti S, et al. Effect of interval (7 or 11 weeks) between neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and surgery on complete pathologic response in rectal cancer: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial (GRECCAR-6). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(31):3773-3780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.6049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaltenmeier C, Shen C, Medich DS, et al. Time to surgery and colon cancer survival in the United States. Ann Surg. Published online December 10, 2019. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marco MR, Zhou L, Patil S, et al. ; Timing of Rectal Cancer Response to Chemoradiation Consortium . Consolidation FOLFOX6 chemotherapy after chemoradiotherapy improves survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: final results of a multicenter phase II trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(10):1146-1155. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbaro B, Vitale R, Valentini V, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in monitoring rectal cancer response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(2):594-599. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maas M, Lambregts DMJ, Nelemans PJ, et al. Assessment of clinical complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer with digital rectal examination, endoscopy, and MRI: selection for organ-saving treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3873-3880. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4687-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. CONSORT Diagram.