Abstract

Short of a vaccine, frequent and rapid testing, preferably at home, is the most effective strategy to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Herein, we report on a single stage and two-stage molecular diagnostic tests that can be carried out with simple or no instrumentation. Our singe stage amplification is reverse transcription Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP) with custom designed primers targeting the ORF1ab and the N gene regions of the virus genome. Our new two-stage amplification, dubbed Penn-RAMP, comprises of Recombinase Isothermal Amplification (RT-RPA) as its first stage and LAMP as its second stage. We compared various sample preparation strategies aimed at deactivating the virus while preserving its RNA and tested contrived and patient samples, consisting of nasopharyngeal swabs, oropharyngeal swabs, and saliva. Amplicons were detected either in real time with fluorescent intercalating dye or after amplification with the intercalating colorimetric dye LCV that is insensitive to sample’s PH. Our single RT-LAMP tests can be carried out instrumentation-free. To enable concurrent testing of multiple samples, we developed an inexpensive heat block that supports both the single-stage and two-stage amplification. Our RT-LAMP assay and Penn-RAMP assay have, respectively, analytical sensitivity of 50 and 5 virions per reaction. Both our single and two-stage assays have successfully detected SARS-CoV-2 in patients with viral loads corresponding to RT-qPCR threshold cycle smaller than 32 while operating with minimally processed samples, without nucleic acid isolation. Penn-RAMP provides a ten-fold better sensitivity than RT-LAMP and does not need thermal cycling like PCR assays. All reagents are amenable to dry, refrigeration-free storage. The herein described SARS-CoV-2 test is suitable for screening at home, at the point of need, and in resource poor settings.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Coronaviruses are a large family of RNA viruses including human coronaviruses (HCoV)-229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1 that typically cause mild to moderate respiratory illnesses1,2 with the exceptions of the fatal Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV)3,4 and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS)5. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in the late 2019, causing a global pandemic, infecting tens of millions of individuals, and causing over a million deaths and severe economic disruption. Short of a vaccine, effective control of the pandemic requires frequent, rapid turn-around screening of asymptomatic individuals6,7.

Most medical centers use reverse-transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) to detect SARS-COV-2 in nasopharyngeal swab samples, oropharyngeal swab samples, saliva, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, sputum, and feces8. RT-PCR tests are, however, carried out in well-equipped laboratories that lack the capacity to frequently screen the entire population. Furthermore, a significant time gap between sample collection and results delays the isolation of potentially contagious individuals challenging pandemic control efforts. The need to deliver samples to collection sites exposes individuals to infection risk and is inconvenient. Rapid, point-of-care molecular diagnostic tests for COVID-19 are needed.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, we reported on two simple closed-tube molecular tests for COVID-19 that can be carried out in the clinic and at home by minimally trained personnel without any sophisticated equipment9. We selected the Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP)10 that does not require thermal cycling and can be incubated with a heat block, a water bath, or even equipment-free, with an exothermic chemical reaction11–13. For amplicon detection, we use either (A) the colorimetric intercalating dye Leuco Violet Crystal14 that changes from colorless in the absence of amplicons to violet in the presence of dsDNA and can be detected by unaided eye or (B) fluorescent intercalating dye that can be excited and monitored with a smartphone or with a simple USB camera15,16. We prefer the LCV colorimetric dye over the more commonly used phenol red pH indicator17 because samples such as saliva vary in their pH and may alter the color of the pH indicator even in the absence of amplification, yielding false positives.

Our second test, dubbed Penn-RAMP, relies on two stage amplification. The first stage of Penn-RAMP is Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RT-RPA)18 and its second stage is LAMP. We developed the Penn-RAMP for high level, nested multiplexing to co-detect multiple co-endemic pathogens (as many as 16 different targets were demonstrated)18. Serendipitously, Penn-RAMP provides better sensitivity, by as much as a factor of 10, and is less inhibited by contaminants than LAMP alone. Hence, Penn-RAMP is beneficial even in a single plex setting. Here, we carry out both tests: Penn-LAMP and Penn-RAMP in a closed tube, avoiding the need to open an amplicon rich tube and risking contamination of the work area.

At the time of our earlier report9, we tested our assays with contrived samples consisting of synthesized DNA that mimics the actual viral sequence since COVID-19 cases in the USA were rare and patient samples were not available. Unfortunately, this is no longer the case. Here, we describe refinements to our tests, compare and optimize sample preparation strategies, and report on tests of patient samples in comparison with the RT-PCR gold standard. Furthermore, to enable easy adaptation of our test for use at the point of need, we have developed a simple heat block to incubate the polymerase amplification.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

Clinical specimens were collected during the first week after hospitalization (likely a few days after symptoms’ onset) from confirmed SARS-CoV2-positive patients in the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania following informed consent under protocols approved by the institutional review board (protocol # 823392). Because SARS-CoV-2 titers peak around the time of symptom onset and fall thereafter19, most samples contained low viral load. Nasopharyngeal samples were collected using flocked swabs (Copan Diagnostics) and eluted in 2-ml of CDC-compliant viral transport medium (VTM) containing Hanks’ buffered salt, 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin, gentamycin, and amphotericin20, or in water. Saliva samples were self-collected by the patient. All samples were first deactivated in biosafety level 2 plus laboratory by being added directly to the lysis buffer (Qiagen kit, Cat. No. 52904/52906), vortexed, and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes, or by heating at 56°C for 1 hour in the absence or in the presence of RNase inhibitor.

SARS-CoV-2 virus (USA-WA1/2020 strain) was obtained from BEI and propagated in the Vero E6 cells.

All viral RNA was extracted from 140 ul of samples using the Qiagen QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 52904/52906), suspended in 50 ul of ddH2O, and quantified with standard qRT-PCR (see Supporting Information) by utilizing Twist Synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA Control (MN908947.3, Twist Bioscience) as reference.

For direct RT-LAMP, RT-RPA and Penn-RAMP, a 2–4 μL unprocessed clinical specimen or contrived sample was directly added to the RT-LAMP and the Penn-RT-RAMP reaction buffers. The standard qRT-PCR was carried out in parallel with extracted RNA from these clinical specimens to serve as “gold standard” results.

LAMP Primer Design

Complete genome sequences of various SARS-CoV-2 (Table S1) were aligned and analyzed with Clustal X (http://www.clustal.org/clustal2/) to identify conserved sequences, which then were compared with sequences of other coronaviruses (Table S1) to assure differentiation. We elected to target conserved sequences within the ORF1ab and the N gene (Figures S1 and S2) because of their high homology among SARS-CoV-2 sequences and high divergence from all other known coronaviruses. Moreover, infected cells express sub genomic mRNA21, increasing abundance of the N gene sequences in the samples and enhancing assay sensitivity.

We designed our LAMP primer sets with the PrimerExplorer V5 software (Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd), and verified primers’ specificity with a BLAST search of the GenBank nucleotide database. A few LAMP primer sets were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) and tested, and the ones documented in Table S2 were selected for further use.

RT-LAMP Assay

The LAMP reaction mix contained 1 X Isothermal MasterMix (ISO-001, OptiGene, UK) and primers (Table 1). During assay development, LAMP amplification was carried out with a 10 μL reaction mix that included 1 μL of synthesized templates (Table S3) or purified RNA of various concentrations, and incubated in a Thermal Cycler (BioRad, Model CFD3240) at 63°C for 40 minutes. For RNA detection, 0.2 U/μL AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega) was added to each LAMP reaction mix. Non-template controls (NTC) were included with each run to ensure absence of false positives.

Table 1:

Sensitivity of direct RT-LAMP, RT-RPA, and Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 eluted from nasal swabs (contrived samples)*.

| Swab elution media | Spiked samples | RT-LAMP** | RT-RPA** | Penn-RAMP** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTM | 10000 particles/reaction | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| 1000 particles/reaction | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | |

| 100 particles/reaction | 2/4 | 1/4 | 4/4 | |

| 10 particles/reaction | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

| 0 particles/reaction | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

|

| ||||

| Water | 10000 particles/reaction | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| 1000 particles/reaction | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | |

| 100 particles/reaction | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | |

| 10 particles/reaction | 0/4 | 0/4 | 3/4 | |

| 0 particles/reaction | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

We submerged a nasal swab in 3 mL of VTM and water and spike SARS-CoV-2 into each of them to prepare contrived nasal swab samples.

The table documents the fraction of positive results.

Colorimetric RT-LAMP Detection of SARS-CoV-2

We prepared LCV14 solution containing 0.5 mM crystal violet (CV), 30 mM sodium sulfite, and 5 mM β-cyclodextrin and stored at −20°C until use. 5.5 μL of prepared LCV dye, 0.5 μL AMV Reverse Transcriptase (10 U/μL), and 2~4 μL sample were added to a 25-μL LAMP reaction volume. For field use, we dried LCV14. A 10-μL volume of the mixture was dispensed into a 200-μL microtube and dried at 60°C for 60 min in a vacuum oven to remove the solvent. When running RT-LAMP with dried LCV, a 10-μL LAMP reaction buffer was added to rehydrate the dried LCV dye. The RT-LAMP reaction was performed with either the Loopamp DNA amplification kit (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Japan) or OptiGene kit (ISO-001, OptiGene, USA). For concurrent fluorescence monitoring and LCV colorimetric detection, the OptiGene kit is preferred. The reaction mixes were incubated with our benchtop thermal cycler (BioRad, Model CFD3240), miniPCR 8 (miniPCR Bio), and our custom-made block heater at 63°C for up to 40 min. The LCV color change was observed at the end of the incubation process by naked eye, and, if desired, can be recorded with a smartphone.

Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP

Penn-RAMP consists of two isothermal amplification processes: RT-RPA (38°C) and LAMP (63°C). We carried out the RT-RPA amplification in the lid of the tube and the LAMP in the tube itself. The RT-RPA reaction mix included 480 nM of each LAMP F3 and B3 primers, 1× rehydrated twistAmp® Basic buffer (twistAmp® Basic kit, TwistDx Limited, Cambridge, UK), 14 mM Mg(CH3COO)2, 0.2 U/μL AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega), and 1~2 μL purified SARS-CoV-2 RNA or patient sample. The sample was inserted in the tube lid together with the RPA mix. The LAMP reaction mix is as described above, but without F3/B3 primers and without target. The ratio of RPA and LAMP reaction mixtures’ volumes was kept at 1:9 to prevent the inhibition of the LAMP reaction22. Typically, we used an RPA volume of 5 μL and a LAMP volume of 45 μL. After loading the tube lid with the RPA mix and the tube itself with the LAMP mix, the tube was sealed and remained so throughout the entire process, protecting the work area from exposure to amplicons. The closed tube was first incubated in our bench top thermal cycler or in the miniPCR (for colorimetric detection) with the lid and block temperatures at 38°C. After 15–20 min, the tube was either centrifuged or flipped back and forth a few times to blend the RPA and LAMP reaction volumes. The tube was then incubated with both the lid and block temperatures at 63°C for 40 min with real-time signal monitoring and/or end point colorimetric detection.

RT-RPA

The RT-RPA experiment was carried out with 10 μL rehydrated (1×) RPA reaction mix (TwistAmp® Exo kit) containing 420 nM each of LAMP F3/B3 primers (Table 1), 14 mM Magnesium Acetate (MgOAc), 120 μM Exo-RPA Probe (synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, Table S4), 0.2 μL AMV Reverse Transcriptase (10 U/μL), and 1 μL SARS-CoV-2 RNA (National Sharing Platform for Reference Materials, China). The reaction mix was kept on ice prior to incubation. After vortexing, the reaction mix was incubated in a Thermal Cycler (BioRad, Model CFX96) at 38°C with a plate-read every 30 sec.

Inhibition Effect of Swab Collection Medium and of Saliva on Direct RT-LAMP

Contrived swab and saliva samples were prepared by spiking inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virions into VTM, saline solution (0.9%), water, and saliva. These samples were treated with and without heating and in the presence and absence of our home-made RNase inhibitor TCEP/EDTA comprised of 1 ml of 0.5 M EDTA (pH = 8); 2.5 ml of 0.5 M Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP-HCl; Millipore Sigma, 580567); 0.575 ml of 10 N NaOH (final concentration 1.15 N); and 0.925 ml of UltraPure water to a final volume of 5 ml23. After RNA extraction, CDC SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was used to quantify the virus titer with a previously prepared calibration curve (Figure S3). The SARS-CoV-2 titer of the contrived samples was adjusted to ~40 virions per microliter (Figure S3C). The threshold time provided a metric to evaluate inhibition effects of the swab collection medium and saliva on direct RT-LAMP.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Specificity of Our RT-LAMP Assay

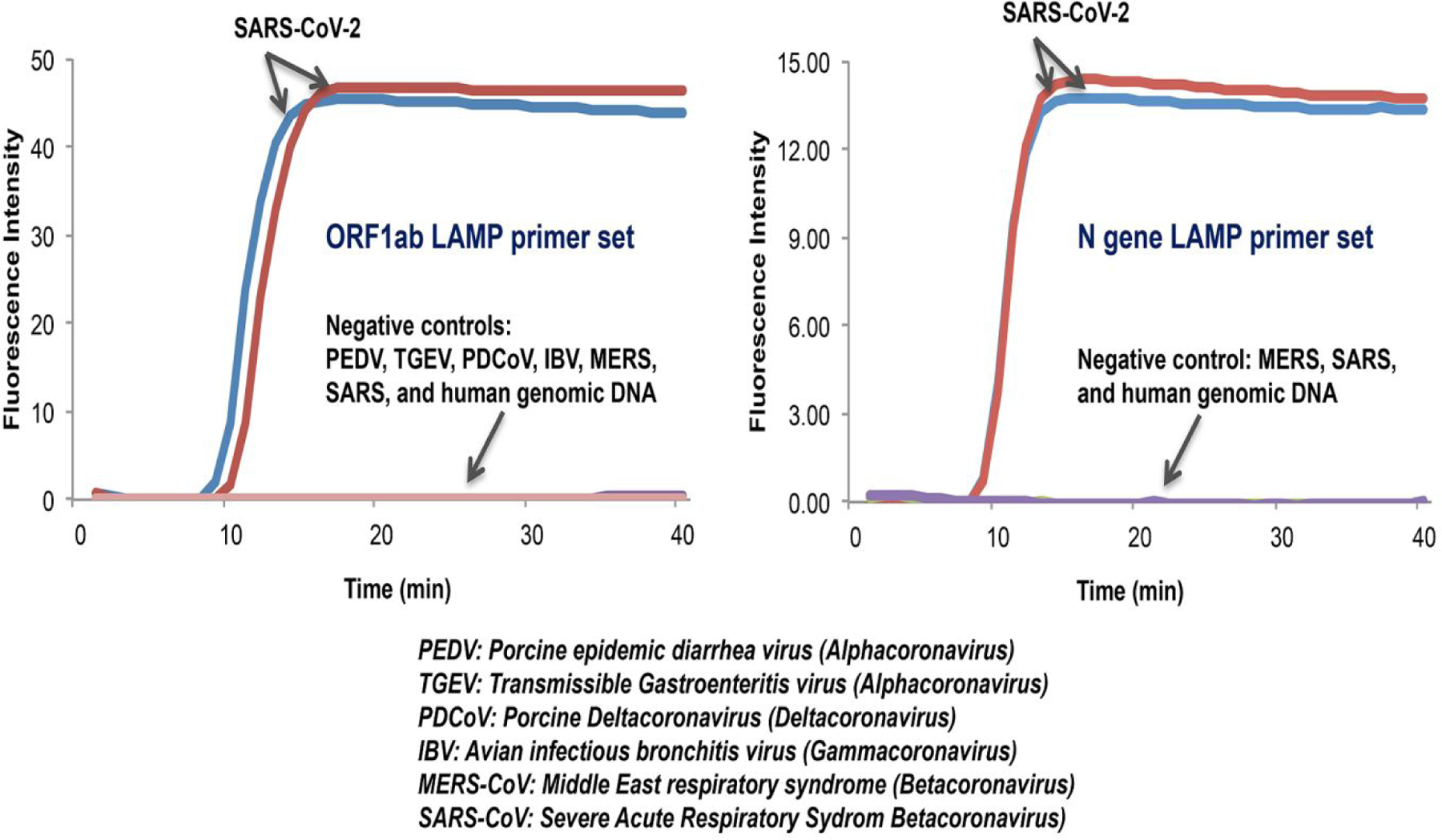

In addition to examining COVID-19 RT-LAMP specificity in silico (Figures S1 and S2), we tested samples of other available coronaviruses, such as alphacoronaviruses (PEDV and RGEV), Gammacoronavirus (IBV), deltacoronavirus (PDCoV), and betacoronavirus (MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV). Only SARS-CoV-2 samples produced a positive signal (Figures 1A and 1B). We did not observe any false positives.

Figure 1: The SARS-CoV-2 ORF1ab and N gene LAMP primer sets are specific.

Only samples with SARS-CoV-2 produced a positive signal, while negative controls (PEDV, TGE, PDCoV, IBV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV) did not show any amplification signal. 104 copies of coronaviruses genome RNAs (PEDV, TGE, PDCoV, IBV), cDNA (MERS-CoV), or synthetic DNA (SARS-CoV) were added to each reaction. Reverse transcriptase (Promega) was included in the LAMP reaction mix.

Analytical Performance of COVID-19 RT-LAMP Assay, RT-RPA assay, and Penn-RT-RAMP Assay

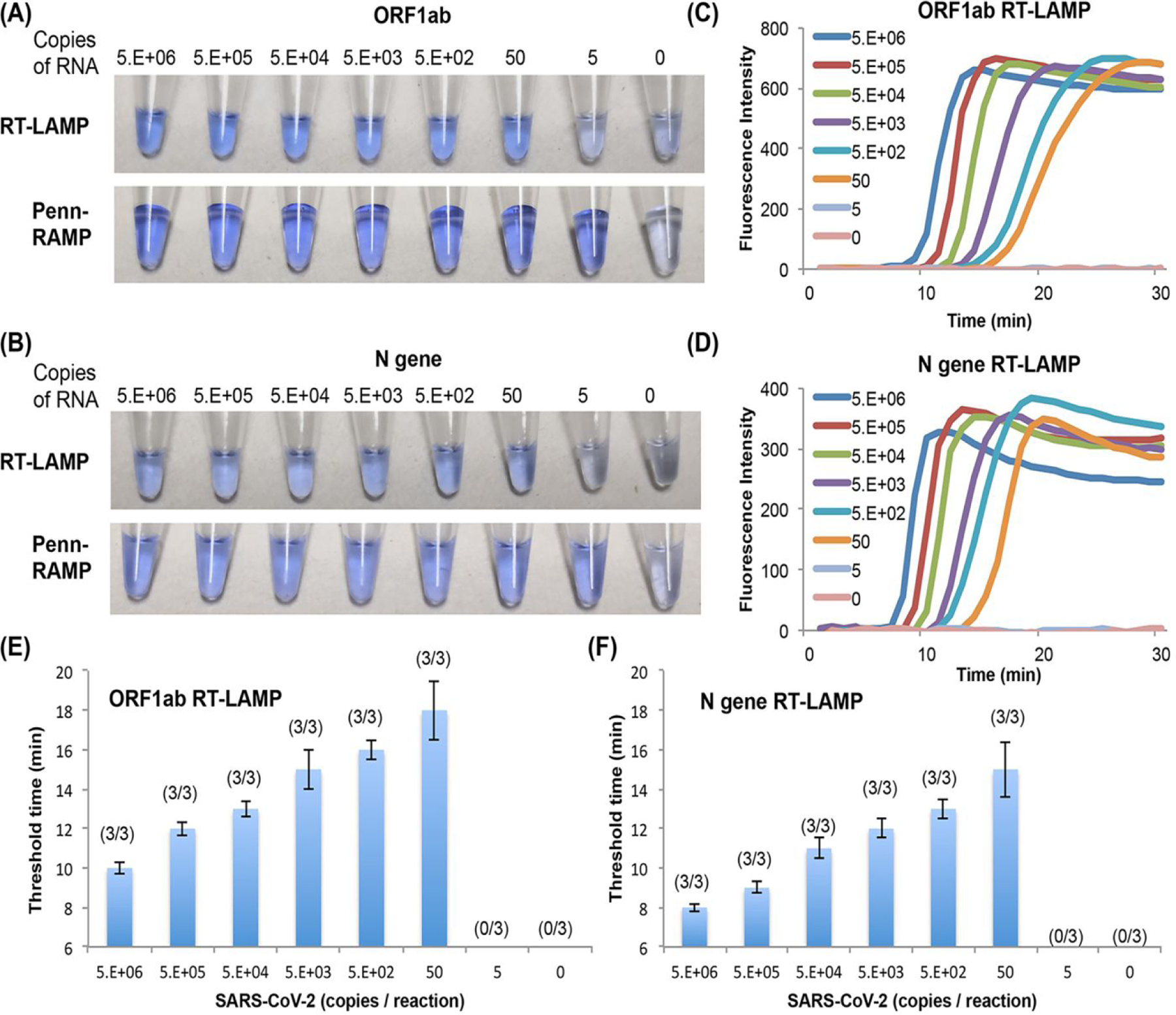

We prepared dilution series and carried out RT-LAMP (Figure 2), RT-RPA with F3/B3 primers (Figure S4) and Penn-RT-RAMP (Figure 2) with the ORF1ab and N gene primer sets and purified SARS-CoV-2 RNA as templates. We used, respectively, 25 μL and 50 μL of OptiGene buffer augmented with LCV dye for RT-LAMP and Penn-RAMP. The presence of LCV dye in the LAMP buffer had no apparent inhibitory effects and allowed us to monitor the LAMP in real time with the fluorescence dye included in the OptiGene buffer. The RT-RPA was monitored in real time with fluorescent EXO-RPA probes (Table S4). All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

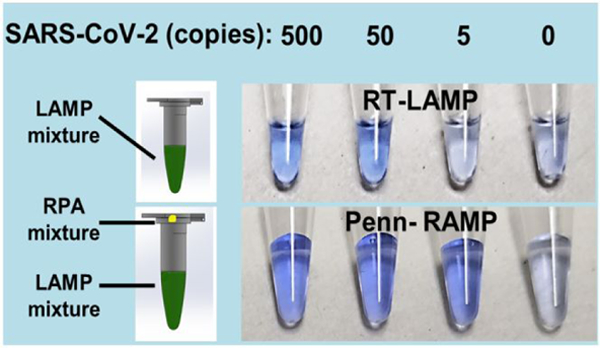

Figure 2: Real Time and Colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2.

(A) and (B) Visual end point detection (LCV dye) of SARS-CoV-2 amplicons with our direct COVID-19 RT-LAMP and our Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP with ORF1ab and N gene LAMP primer sets, respectively. (C) and (D) are the LAMP amplification curves corresponding to RT LAMP in (A) and (B). (E) and (F) The LAMP threshold time in (C) and (D) as a function of SARS-CoV-2 concentration (n = 3).

RT-RPA has successfully amplified the targets while operating with somewhat shorter F3/B3 LAMP primers (18–22 nt) than common (28–35 nt). The RT-LAMP with both colorimetric LCV dye and fluorescence dye (Figures 2E and 2F) and the RT-RPA detect as few as 50 RNA copies / reaction with either ORF1ab or N gene primers. The LAMP primer set targeting the N gene amplified 2–5 min faster compared to the other reported SARS-CoV-2 LAMP primer sets due to the shorter amplicon (Figure 2F).

Since visual detection does not require any instrumentation, the colorimetric LAMP assay is attractive for home use. The LCV dye is nearly colorless in the absence of dsDNA and turns deep violet in the presence of dsDNA, enabling detection of amplicons by eye. The results of our colorimetric RT-LAMP detection are consistent with our real time amplification curves, detecting as few as 50 targets per reaction (Figures 2A top and 2B top). Penn-RAMP provides better sensitivity than standalone RT-LAMP (and standalone RT-RPA), changing color with as few as 5 copies/reaction with both the ORF1ab and the N primer sets (Figures 2A bottom, 2B bottom, and Figure S5). In addition, the LCV dye based colorimetric detection has advantages over phenol red (Supplementary Results and Discussion).

Infectivity of Coronavirus after Heat Treatment

We evaluated various rapid sample preparation methods, aiming to inactivate the virus while maintaining viral RNA’s integrity. Out of safety concerns, we carried out our initial experiments with avian gamma-coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) isolates (103.2 EID50 /ml) as a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Methods). The IBV intact virus was inactivated entirely (no infected cells were observed) after incubation at 95°C for ≥5 min, 70°C for ≥10 min, and 56°C for ≥30 min (Table S5). At shorter incubation times such as 5 min at 70°C, viral activity was observed at high virus concentrations. We also incubated SARS-CoV-2 for 5 minutes at 70°C and at 95°C in a BSL3, obtaining similar results to the ones obtained with IBV.

The Effect of RNase inhibitors on RNA Integrity after Heat Treatment

Next, we examined the effect of heat treatment and RNase inhibitors on RNA Integrity, using RT-qPCR’s threshold cycle (Ct) as the figure of merit (Supplementary Methods). We carried out our experiments with IBV suspended in water in absence of RNase inhibitor, in the presence of the RNase inhibitor iNtRON (optimal working temperature 42°C, Cat #. 25011, iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea), and in the presence of our custom-made TCEP/EDTA RNase inhibitor (Figure S6). As a result of university safety regulations, SARS-CoV-2 had to be deactivated prior to our experiments, which forced us to use iNtRON at temperatures greater than recommended by the manufacturer. In all cases, the threshold cycle (Ct) increased as the incubation time and temperature increased, indicating degradation of RNA. Specifically, the addition of our custom RNase inhibitor (TCEP/EDTA) resulted in a 2-fold (5 min incubation at 70°C) and ~4-fold (95°C, 5 min) reduction in the number of templates. Five minutes heating at 70°C and 95°C resulted, respectively, in ~8-fold and ~16-fold reduction in the number of templates both in the presence and absence of iNtRON, indicating that iNtRON had little effect, if any. Among samples incubated under similar conditions, the Ct values decreased from pure water to commercial RNase inhibitor (optimal temperature 42°C) to our custom-made RNase inhibitor buffer (TCEP/EDTA). We see little benefit from commercial RNase inhibitor, probably because its working temperature is too low to protect RNA well at 70°C and 95°C.

Although our preferred sample preparation is 5 min incubation at 95°C in the presence of TCEP/EDTA, at the time of our experiments, our office of environmental safety has only approved incubation at 56°C for 1 hour for patient sample deactivation. Thus, all our patient samples were incubated at 56°C for 1 hour in the presence of the RNase inhibitor RNasin® (Cat. N2615, Promega) with optimal temperature ranging from 50°C to 70°C. Samples treated with RNasin® exhibited better results (Table S6, shaded area) than samples untreated with RNasin®. TCEP/EDTA yielded similar results to that of RNasin® (Table S6).

The Effect of Swab Elution Media on RNA Integrity after Heat Treatment

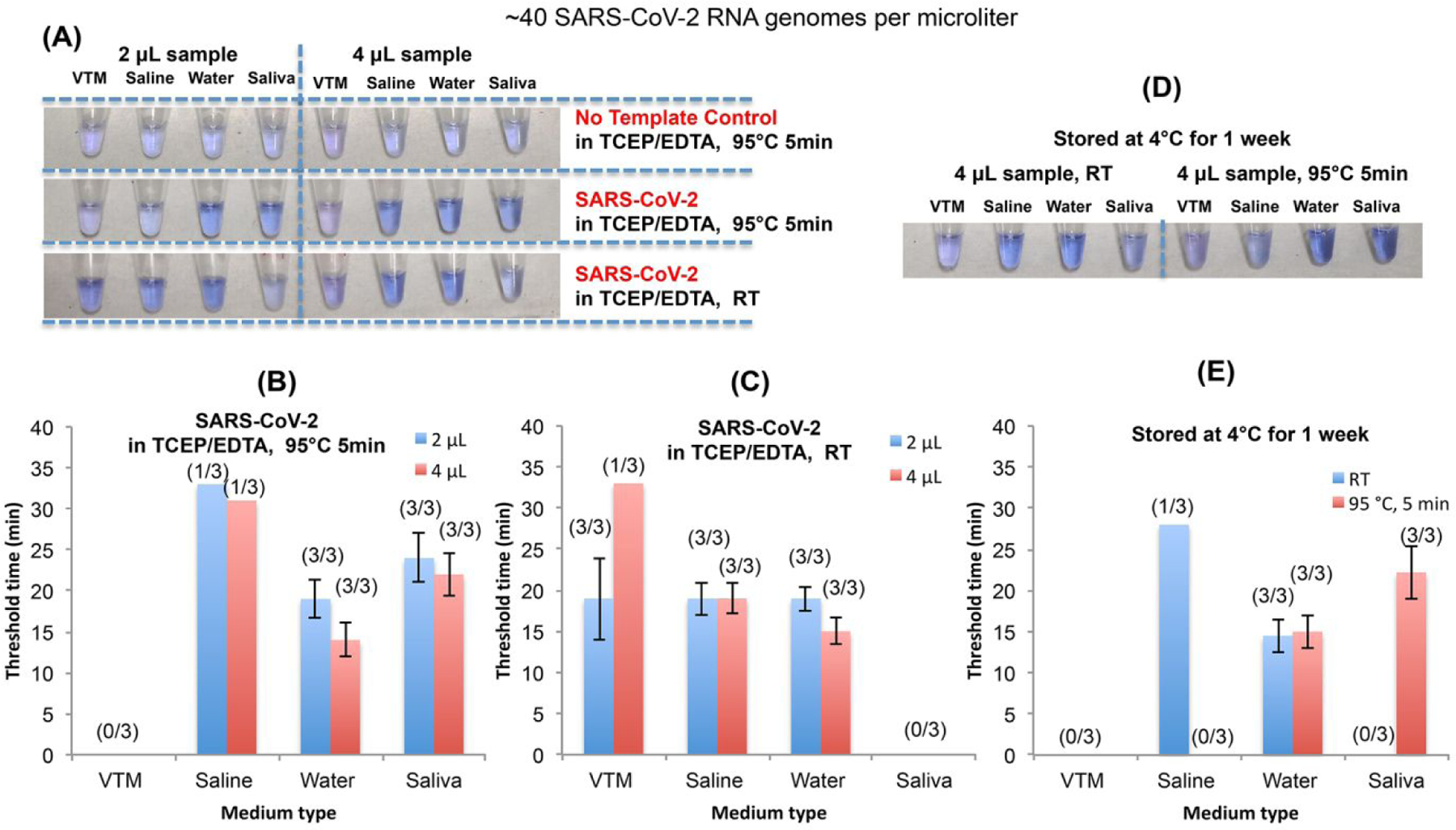

The swab elution media plays a key role in RNA degradation and polymerase inhibition (in the absence of purification). To investigate the optimal swab elution media, we spiked heat-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 high-titer patient sample into VTM, saline solution, and water in the presence of TCEP/EDTA. The concentration of templates in each medium was quantified with the CDC-approved SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR after RNA extraction. The final concentration of viral RNA genomes from intact and damaged viral particles in these spiked samples was ~40 copies per microliter. Then, we carried out direct OptiGene RT-LAMP (without RNA isolation) on these samples.

Viral Transport Medium (VTM) is frequently used to elute and preserve viral particles collected with swabs and to maintain viral viability for virus culturing. Although preservation of viral activity is neither needed nor desired for molecular tests, many laboratories still use VTM for molecular tests. Thus, we examined the effect of VTM after heat treatment on direct RT-LAMP. VTM samples spiked with SARS-CoV-2 (40 virions/μL) yielded true positives in the absence of heat treatment, but puzzlingly, false negatives in the presence of heat treatment (95°C, 5 min). We suspect that heat treatment of VTM in the presence of TCEP/EDTA resulted in RNA degradation, reducing the number of templates available to the amplification process. To test this hypothesis, we carried RT-qPCR with purified heat-treated samples and observed significant delay in the threshold cycle of virions suspended in VTM (Figure S7) possibly due to the presence of RNase activity in the VTM (perhaps introduced with the fetal bovine serum) that was not completely suppressed by incubation and presence of TCEP/EDTA. Others24 have reported positive tests with heat-treated VTM at 95°C for 1 minute but at much greater virus concentrations than in our experiments.

In our hands, like in the case of VTM, heat treatment of saline solution spiked with virus had an adverse effect (Figure 3B), perhaps due to RNA degradation. Surprisingly, Surprisingly, virus spiked in molecular water provided nearly the same threshold times in the presence and absence of heat treatment. Incubation at 95°C (5 min) had little adverse effect, if any, on virions suspended in water (Figure S7).

Figure 3: Inhibition effect of swab sample collection medium and saliva on direct RT-LAMP.

(A) The impact of VTM, saline, water, and saliva on colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 with LCV dye in the presence and absence of TCEP/EDTA and/or heat treatment. (B) and (C) The LAMP threshold time as a function of medium type in the presence (B) and the absence of heat treatment (C) (n = 3). (D) Colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 after storing the samples at 4°C for a week. (E) The LAMP threshold time in (D) as a function of medium type and heat treatment (n = 3). RT = room temperature. All LAMP experiment was carried out with OptiGene master mix (ISO-001) and N gene LAMP primer set.

VTM even when refrigerated did not serve as an effective storage medium, while molecular water provided the best storage medium with nearly the same threshold time after a week of refrigeration (4°C) as that of freshly prepared samples (Figures 3D and 3E). In summary, water/TCEP/EDTA appears to be a superior swab collection medium and by far less expensive than VTM.

Inhibitory Effects of Swab Elution Media on Direct RT-LAMP

Next, we examine the inhibitory effects of swab elution media on direct RT-LAMP. Without heat treatment of the contrived swab samples, water and saline solution, both with TCP/EDTA, were the best elution media, providing the smallest threshold times and enabling positive identification of all spiked samples without any false positives (100% specificity) (Figure 3A and 3C). When the sample is virions suspended in water, our direct RT-LAMP detects down to 80 virions/reaction and produces a much lower threshold time than VTM (Figures 3C), suggesting that VTM inhibits polymerase. Such inhibition would not affect tests operating with purified RNA but has adverse effect when unprocessed samples are added directly into the reaction mix. This is evident from samples with 4 μL VTM having significantly greater threshold times than samples with 2 μL of VTM (half the number of templates) (Figure 3C).

Inhibitory Effects of Saliva on Direct RT-LAMP before and after Heat Treatment

Saliva is becoming the sample of choice for SARS-CoV-2 screening because of its ease of collection, amenability to self-collection, minimal risk to health care workers, and absence of need for swabs and storage media that may be in short supply. In contrast to VTM, saline solution, and water, 95°C incubation for 5 min in the presence of TCP/EDTA enhanced our ability to detect virions spiked in saliva (Figure 3B). In the absence of heat treatment, all our saliva samples yielded false negatives (Figure 3C). It appears that heat treatment diminishes inhibitors in saliva and affects favorably saliva’s rheology. Doubling the saliva volume in the reaction mix reduced threshold time, suggesting that the incubation process neutralized LAMP inhibitors. Saliva samples incubated at 95°C for 5 min in the presence of TCP/EDTA were successfully stored for a week without any significant degradation of viral RNA.

Direct Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP outperforms standalone Direct RT-LAMP and standalone Direct RT-RPA

When testing purified RNA, Penn-RAMP provided about ten-fold better analytical sensitivity than standalone RT-LAMP and standalone RT-RPA (Figures 2 and S4). Does this advantage carry over when operating with minimally processed samples? We compared the detection of SARS-CoV-2 eluted from nasal swabs (contrived samples) (Table 1). Penn-RAMP detected successfully 4/4 of the samples with 100 virions in VTM while standalone RT-LAMP and standalone RT-RPA detected, respectively, only 2/4 and 1/4 of similar samples as positives. All three assays detect 4/4 of samples with 100 virions in water as positive. Penn-RAMP successfully identifies 3/4 of the samples with 10 virions in water as positive while standalone RT-LAMP and standalone RT-RPA yield false negatives for all these samples.

Clinical Performance of COVID-19 Direct RT-LAMP Assay and Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP Assay for Colorimetric (LCV) Detection of Swab VTM and Water Samples

To examine the performance of our closed-tube molecular tests with minimal sample preparation such as might be used at home and in poor resource settings, we evaluated the COVID-19 direct RT-LAMP and Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP assays with clinical samples obtained by eluting swabs in VTM (Table S7, N=40). After incubating the sample at 56°C for 1 hour, 2 μL of the VTM were added to the reaction mix. Our closed single stage RT-LAMP and our Penn-RAMP had, respectively, sensitivities of 9/19 (47%) and 16/19 (84%) compared to the CDC EUA RT-PCR gold standard. Our RT-LAMP and Penn-RAMP detected, respectively, samples with RT-qPCR Ct<28 and Ct<36 without any false positives (100% specificity). Importantly, both our assays operated without nucleic acid isolation. Penn-RAMP outperformed RT-LAMP likely because of its higher amplification efficiency and greater tolerance to inhibitors in the VTM.

Next, we eluted different swabs collected from the same patient into water/TCEP/EDTA and VTM/RNasin® and compared the RT-LAMP performance for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in these two media (Table S8, N=5). Our direct RT-LAMP identified all (5/5) RT-qPCR positive (Ct<32) eluates in water but only 4/5 RT-qPCR positive eluates in VTM. The VTM sample with RT-qPCR Ct> 28 yielded a false negative. Consistent with our previous data, water eluates produced shorter threshold times than VTM eluates.

Performance of COVID-19 Direct RT-LAMP and Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP Assay for Colorimetric (LCV) Detection of Virions in Saliva

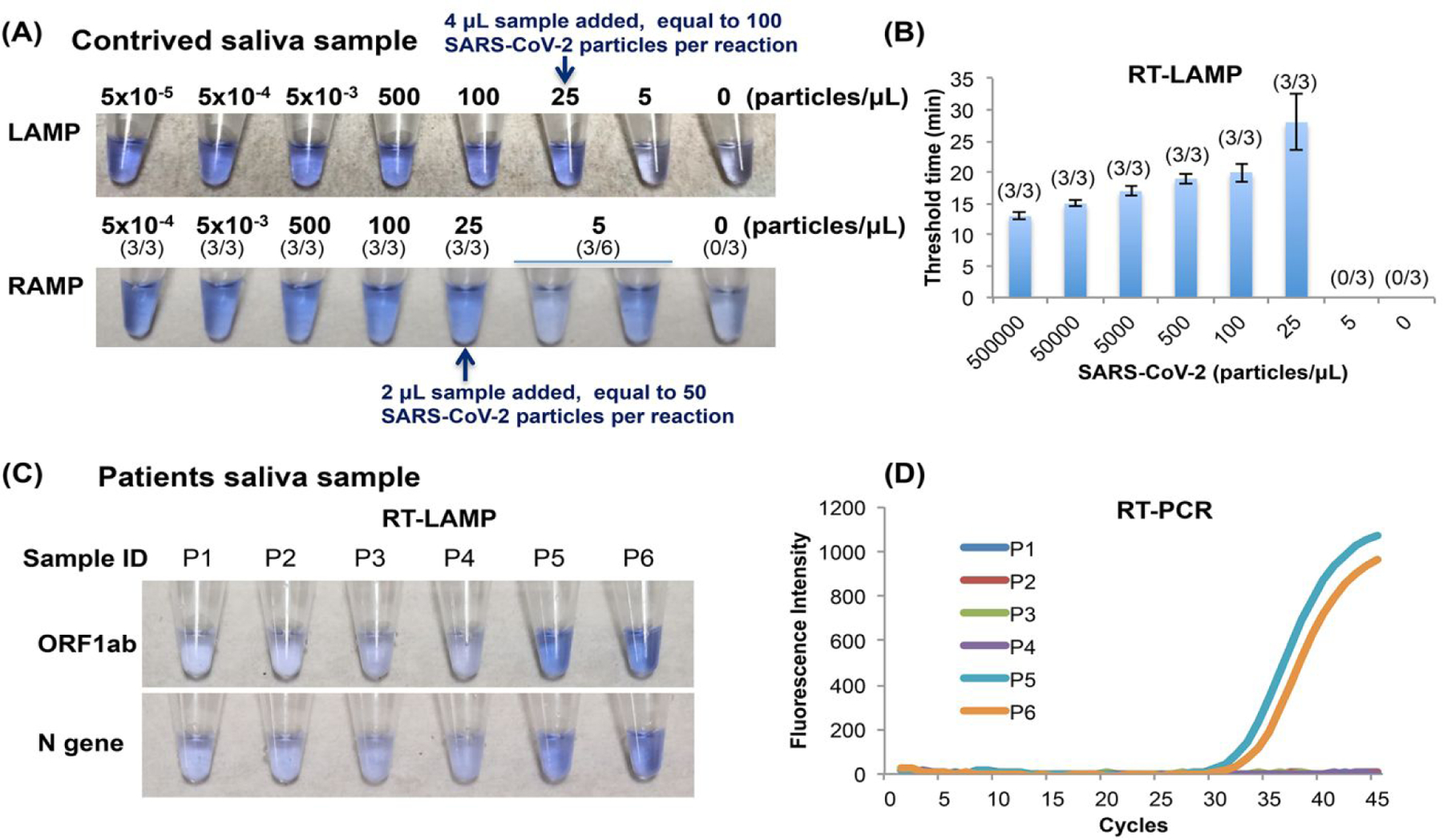

Saliva collection is both noninvasive and convenient and has been advocated as a reliable medium for SARS-CoV-2 screening25–27. Here, we investigate colorimetric detection of saliva with our direct RT-LAMP (Figures 4A top and 4B) and Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP (Figure 4A bottom). We carried out our experiments with both dilution series of contrived samples and with actual patient samples.

Figure 4: Saliva sample detection.

(A) Colorimetric detection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in contrived samples comprised of virions spiked in saliva. (B) RT-LAMP threshold time as a function of the SARS-CoV-2 virus concentration (n = 3). (C) Colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva samples from suspected COVID-19 patients. A 4 μL of saliva was directly added to RT-LAMP reaction mix. (D) RT-PCR amplification curves of the saliva samples in (C).

When operating with contrived samples, RT-LAMP targeting the N gene has successfully detected SARS-CoV-2 in 4 μL of saliva at the titer of 25 virions/μL (100 virions/reaction) (Figures 4A top and 4B) while Penn-RAMP successfully detected 2 μL of saliva at the titer of 25 virions/μL (50 virions/reaction) and less reliably (3/6) at titer of 5 virions/μL (Figure 4A bottom).

At the time of our experiments, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania did not collect saliva samples from patients. Hence, we had only limited access to actual patient saliva samples. We tested six patient saliva samples. Each of these samples was subjected to standard RT-qPCR test. Only two of the samples were positive with an estimated viral load of 25 virions μL (Figure 4D and Figure S3B). We added TCEP/EDTA to all patient samples, heated the samples to 95°C for 5 min, and then tested each of the samples with our direct RT-LAMP; with one assay targeting the ORF1ab and the other targeting the N gene (Figure 4C). All the positive samples were detected as positive and all negative samples were detected as negative by our direct RT-LAMP, attesting to the efficacy of our proposed assay.

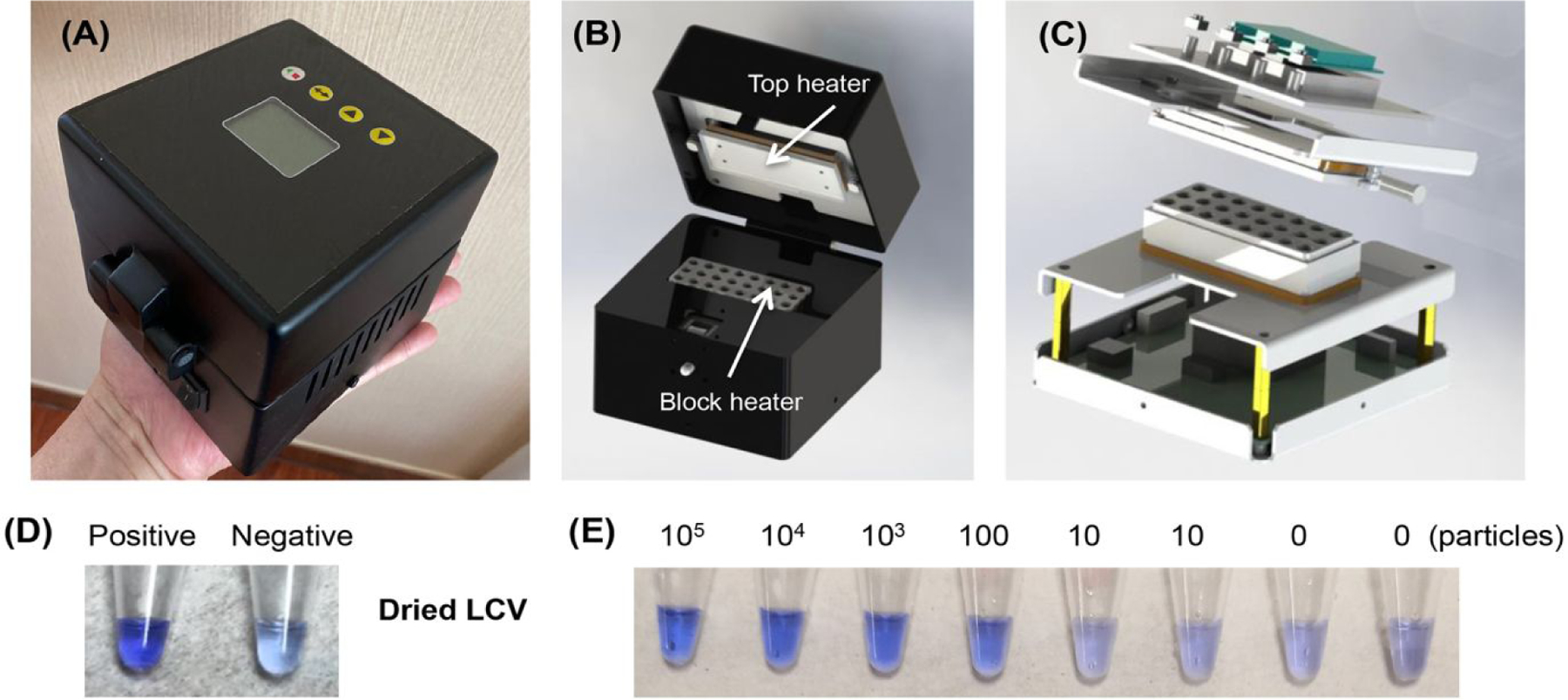

Block Heater and Dried Reagents

Although our direct RT-LAMP and Closed-Tube Penn-RAMP can be incubated either in a water bath, in a domestic oven with temperature control, or with an exothermic chemical reaction without any electrical power11,12, we developed an inexpensive (~ $75), portable block heater (Figures 5A, 5B, and 5C), capable of incubating either RT-LAMP or Penn-RAMP, to enable testing in centralized locations such as offices and clinics.

Figure 5: Block heater and dried reagents.

(A), (B), and (C) outside, inside, and exploded views of our block heater. (D) Colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 with dried reaction mix and LCV dye. 103 SARS-CoV-2 virions used in the positive control. (E) Colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 with dry LAMP reaction mixture in the presence of 105, 104, 103, 100, 10, and 0 virions per reaction. These reactions were incubated with our custom-made block heater.

Furthermore, for home and field use, it is desirable to avoid the need for cold chain. To this end, we augmented the lyophilized OptiGene master mix (ISO-DR004) that has both polymerase and reverse transcriptase activities, with vacuum-dried LCV. The performance of the dry reagents was equivalent to that of our wet reagents (Figure 5D), Our RT-LAMP incubated with our block heater successfully detected 100 SARS-CoV-2 virions per reaction (Figure 5E).

CONCLUSIONS

We have designed and tested two sets of primers for SARS-CoV-2 RT-LAMP. One set of primers targets a sequence in the ORF1ab region and the other the N gene. Both primer sets provide efficient amplification and are specific, distinguishing SARS-CoV-2 from other coronaviruses. Our RT-LAMP primer sets were adapted by others with equally good results28,29. Additionally, we have demonstrated colorimetric detection with the intercalating LCV dye that changes from nearly colorless to violet in the presence of amplicons (dsDNA); is visible to the naked eye; and unaffected by sample composition such as PH.

We have used each primer set in our single stage RT-LAMP and in our newly developed two-stage Penn-RAMP to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in contrived and in clinical samples, without RNA isolation. The contrived samples comprised of synthesized oligos replicating segments of the SARS-CoV-2 genome and cell-cultured virions spiked in various media. The patient samples included swabs and saliva collected in the intensive care unit and the emergency room of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. We examined various elution media for the swab samples, ranging from VTM, saline solution, to molecular water.

When testing contrived samples, our RT-LAMP and Penn-RAMP assays successfully detected, respectively, down to 50 and 5 virions per reaction. Our assays operated reasonably well with samples mixed with RNase inhibitor with and without thermal incubation. Our direct RT-LAMP tolerated up to 8% of minimally processed samples that included saliva and swab-collected samples eluted in VTM, water, or saline solution. Among the various swab elution media, we find molecular water to provide best results while VTM inhibits polymerase.

Penn RAMP has better sensitivity and tolerance to contaminants than RT-LAMP alone. Also, it has better specificity, and does not require molecular probes or lateral flow device for amplified products analysis compared with standalone RPA.

In contrast to NEB colorimetric assay that uses phenol purple to detect proton production during polymerase and is susceptible to pH variations among samples, occasionally leading to false positives (Figure S8D), our LCV dye is unaffected by sample pH variability. Our reaction mix and dye are amenable to dry storage, eliminating the need for cold chain.

Since our direct RT-LAMP and the second stage LAMP in Penn RAMP tolerate, respectively, relatively small volumes of unprocessed sample and first stage RPA products, there are limitations to our assays’ sensitivities. These can potentially be addressed with the development of more robust LAMP enzymes and by modifying the second stage LAMP buffer composition to tolerate greater volume of first stage products.

We hope that our test and similar ones can be adapted for home use, enabling individuals to test themselves every morning prior to leaving their house and quarantine themselves when warranted. This modus operandi that provides prompt test results, eliminates the need for potentially contagious individuals queuing at sample collection sites and posing a risk to themselves and others and provides timely information to policy makers to make rational decision critical to the management of the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.El-T was supported by the Fulbright Visiting Scholar Program. H.H.B. was supported, in part, by NIH grant R21 AI134594-01A1 to the University of Pennsylvania and by a gift from Mr. Jeff Horing to UPenn School of Engineering for COVID-19 Research. J.S. was supported, in part, by NIH grant K01 1K01TW011190-01A1 to the University of Pennsylvania. RGC was supported, in part, by NIH grant R33-HL137063 to the University of Pennsylvania and by the Penn Center for Research on Coronavirus and Other Emerging Pathogens. SRW and YL were supported in part by grant R01-AI-140442 to the University of Pennsylvania. Penn Engineering students: Yining Liang, Zihan Yin, Jihao Luo, and Marco Armendariz assisted in developing the block heater. A. Fitzgerald and L. Khatib collected patients’ samples. A part of this paper was previously posted (prior to the availability of SARS-CoV-2 samples) as a preprint on the ChemRxiv9.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gaunt ER; Hardie A; Claas EC; Simmonds P; Templeton KE Epidemiology and Clinical Presentations of the Four Human Coronaviruses 229e, Hku1, Nl63, and Oc43 Detected over 3 Years Using a Novel Multiplex Real-Time Pcr Method. J. Clin. Microbiol 2010, 48, 2940–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zeng ZQ; Chen DH; Tan WP; Qiu SY; Xu D; Liang HX; Chen MX; Li X; Lin ZS; Liu WK; Zhou R Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of Human Coronaviruses Oc43, 229e, Nl63, and Hku1: A Study of Hospitalized Children with Acute Respiratory Tract Infection in Guangzhou, China. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 2018, 37, 363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).WHO, Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). World Health Organization 2003. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70863 (accessed July 17, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- (4).Smith RD Responding to Global Infectious Disease Outbreaks: Lessons from Sars on the Role of Risk Perception, Communication and Management. Soc. Sci. Med 2006, 63, 3113–3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zumla A; Hui DS; Perlman S Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Lancet 2015, 386, 995–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Mina MJ; Parker R; Larremore DB Rethinking Covid-19 Test Sensitivity - a Strategy for Containment. N. Engl. J. Med 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Larremore DB; Wilder B; Lester E; Shehata S; Burke JM; Hay JA; Tambe M; Mina MJ; Parker R Test Sensitivity Is Secondary to Frequency and Turnaround Time for Covid-19 Screening. Sci. Adv 2021, 7, eabd5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).WHO, Laboratory testing of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases: interim guidance 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/laboratory-testing-of-2019-novel-coronavirus-(−2019-ncov)-in-suspected-human-cases-interim-guidance-17-january-2020 (accessed July 17, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- (9).El-Tholoth M; Bau HH; Song J A Single and Two-Stage, Closed-Tube, Molecular Test for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19) at Home, Clinic, and Points of Entry. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Notomi T; Mori Y; Tomita N; Kanda H Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (Lamp): Principle, Features, and Future Prospects. J. Microbiol 2015, 53, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Song JZ; Mauk MG; Hackett BA; Cherry S; Bau HH; Liu CC Instrument-Free Point-of-Care Molecular Detection of Zika Virus. Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 7289–7294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Song JZ; Pandian V; Mauk MG; Bau HH; Cherry S; Tisi LC; Liu CC Smartphone-Based Mobile Detection Platform for Molecular Diagnostics and Spatiotemporal Disease Mapping. Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 4823–4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Li RJ; Mauk MG; Seok Y; Bau HH Electricity-Free Chemical Heater for Isothermal Nucleic Acid Amplification with Applications in Covid-19 Home Testing. Analyst 2021, 146, 4212–4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Miyamoto S; Sano S; Takahashi K; Jikihara T Method for Colorimetric Detection of Double-Stranded Nucleic Acid Using Leuco Triphenylmethane Dyes. Anal. Biochem 2015, 473, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liao SC; Peng J; Mauk MG; Awasthi S; Song JZ; Friedman H; Bau HH; Liu CC Smart Cup: A Minimally-Instrumented, Smartphone-Based Point-of-Care Molecular Diagnostic Device. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 2016, 229, 232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Song JZ; Liu CC; Bais S; Mauk MG; Bau HH; Greenberg RM Molecular Detection of Schistosome Infections with a Disposable Microfluidic Cassette. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 2015, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Tanner NA; Zhang YH; Evans TC Visual Detection of Isothermal Nucleic Acid Amplification Using Ph-Sensitive Dyes. BioTechniques 2015, 58, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Song J; Liu C; Mauk MG; Rankin SC; Lok JB; Greenberg RM; Bau HH Two-Stage Isothermal Enzymatic Amplification for Concurrent Multiplex Molecular Detection. Clin. Chem 2017, 63, 714–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wölfel R; Corman VM; Guggemos W; Seilmaier M; Zange S; Müller MA; Niemeyer D; Jones TC; Vollmar P; Rothe C Virological Assessment of Hospitalized Patients with Covid-2019. Nature 2020, 581, 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Preparation of viral transport medium https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/Viral-Transport-Medium.pdf (accessed July 17, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chu DKW; Pan Y; Cheng SMS; Hui KPY; Krishnan P; Liu Y; Ng DYM; Wan CKC; Yang P; Wang Q; Peiris M; Poon LLM Molecular Diagnosis of a Novel Coronavirus (2019-Ncov) Causing an Outbreak of Pneumonia. Clin. Chem 2020, 66, 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).El-Tholoth M; Anis E; Bau HH Two Stage, Nested Isothermal Amplification in a Single Tube. Analyst 2021, 146, 1311–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rabe BA; Cepko C Sars-Cov-2 Detection Using Isothermal Amplification and a Rapid, Inexpensive Protocol for Sample Inactivation and Purification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117, 24450–24458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ganguli A; Mostafa A; Berger J; Aydin M; Sun F; Valera E; Cunningham BT; King WP; Bashir R Rapid Isothermal Amplification and Portable Detection System for Sars-Cov-2. bioRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wyllie AL; Fournier J; Casanovas-Massana A; Campbell M; Tokuyama M; Vijayakumar P; Warren JL; Geng B; Muenker MC; Moore AJ; Vogels CBF; Petrone ME; Ott IM; Lu P; Venkataraman A; Lu-Culligan A; Klein J; Earnest R; Simonov M; Datta R, et al. Saliva or Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens for Detection of Sars-Cov-2. N. Engl. J. Med 2020, 383, 1283–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).To KK; Tsang OT; Leung WS; Tam AR; Wu TC; Lung DC; Yip CC; Cai JP; Chan JM; Chik TS; Lau DP; Choi CY; Chen LL; Chan WM; Chan KH; Ip JD; Ng AC; Poon RW; Luo CT; Cheng VC, et al. Temporal Profiles of Viral Load in Posterior Oropharyngeal Saliva Samples and Serum Antibody Responses During Infection by Sars-Cov-2: An Observational Cohort Study. Lancet Infect. Dis 2020, 20, 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Xu R; Cui B; Duan X; Zhang P; Zhou X; Yuan Q Saliva: Potential Diagnostic Value and Transmission of 2019-Ncov. Int. J. Oral. Sci 2020, 12, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sherrill-Mix S; Hwang Y; Roche AM; Glascock A; Weiss SR; Li Y; Haddad L; Deraska P; Monahan C; Kromer A Detection of Sars-Cov-2 Rna Using Rt-Lamp and Molecular Beacons. Genome Biol 2021, 22, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Garcia-Bernalt Diego J; Fernandez-Soto P; Dominguez-Gil M; Belhassen-Garcia M; Bellido JLM; Muro A A Simple, Affordable, Rapid, Stabilized, Colorimetric, Versatile Rt-Lamp Assay to Detect Sars-Cov-2. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.