Abstract

Blood smear evaluation of two baboons (Papio cynocephalus) experiencing acute hemolytic crises following experimental stem cell transplantation revealed numerous intraerythrocytic organisms typical of the genus Babesia. Both animals had received whole-blood transfusions from two baboon donors, one of which was subsequently found to display rare trophozoites of Entopolypoides macaci. An investigation was then undertaken to determine the prevalence of hematozoa in baboons held in our primate colony and to determine the relationship, if any, between the involved species. Analysis of thick and thin blood films from 65 healthy baboons (23 originating from our breeding facility, 26 originating from an out-of-state breeding facility, and 16 imported from Africa) for hematozoa revealed rare E. macaci parasites in 31%, with respective prevalences of 39, 35, and 12%. Phylogenetic analysis of nuclear small-subunit rRNA gene sequences amplified from peripheral blood of a baboon chronically infected with E. macaci demonstrated this parasite to be most closely related to Babesia microti (97.9% sequence similarity); sera from infected animals did not react in indirect fluorescent-antibody tests with Babesia microti antigen, however, suggesting that they represent different species. These results support an emerging view that the genus Entopolypoides Mayer 1933 is synonymous with that of the genus Babesia Starcovici 1893 and that the morphological variation noted among intracellular forms is a function of alteration in host immune status. The presence of an underrecognized, but highly enzootic, Babesia sp. in baboons may result in substantial, unanticipated impact on research programs. The similarity of this parasite to the known human pathogen B. microti may also pose risks to humans undergoing xenotransplantation, mandating effective screening of donor animals.

Babesia spp. are intraerythrocytic hematozoa which occur in a wide variety of mammalian hosts and are transmitted by various species of ticks. Certain species have emerged as significant human pathogens in recent years, including the rodent species Babesia microti in North America, the bovine species Babesia divergens in Europe, and as-yet-unnamed species, referred to as WA1, MO1, and TW1, found in the western United States, south-central United States, and Taiwan, respectively (14, 15, 29, 32, 36, 37, 39). The spectrum of infection in humans includes subclinical to fatal infection, the latter occurring most commonly in individuals who are immunocompromised, most notably secondary to asplenia.

Recently we observed fatal hemolytic crises in two profoundly immunosuppressed baboons (Papio cynocephalus) undergoing experimental stem cell transplantation (one allogeneic and one autologous) (2). Greater than 50% of their erythrocytes were found to be infected with typical Babesia-like organisms. Both baboons received blood transfusions from two donors, one of which was shown to be parasitemic, with very rare and delicate intracellular hematozoa most suggestive of Entopolypoides macaci, a Babesia-related parasite described in African and Asian nonhuman primates and, rarely, in humans (8, 12, 13, 23, 24, 26). Detection of these parasites in animals with intact and abrogated immune systems raised important questions regarding their characterization and origins, whether they represented variants of the same species, their prevalences in colony animals, and mechanisms of transmission. The potential effects on research programs of such acute and chronic infections in colony animals are significant. Also, the increasing use of baboon xenografts in humans makes the identification of such infections prior to transplantation mandatory to prevent possible transmission of a zoonotic agent (10).

In this paper we present preliminary findings on the morphologic characterization, prevalence, and phylogenetic affiliation of a piroplasm found to be enzootic in baboons in our breeding facility, some of which originated from a second breeding facility in the United States while others were from foreign sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals studied.

The two baboons in which hematozoa were first noted had undergone total-body irradiation followed by stem cell transplantation (one autologous and one allogeneic); both animals were subsequently treated with cyclosporine and were noted to be profoundly immunosuppressed (2). Sixty-five additional baboons (P. cynocephalus) were subsequently examined as part of this study. Twenty-three of these animals were born and raised in the Medical Lake, Wash., breeding facility administered by the Regional Primate Research Center (RPRC) located at the University of Washington in Seattle. Another 26 originated from the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research in San Antonio, Tex., and were shipped directly to the RPRC without spending time at the Medical Lake breeding facility; animals at both breeding facilities were held in outdoor enclosures and were known to comingle. Sixteen animals were imported from Africa (13 from Ethiopia, 2 from Kenya, and 1 from an unspecified African location) and shipped to the RPRC in Seattle. All animals were housed and cared for in our facilities in accordance with accepted standards (Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) for laboratory animal care.

Single blood samples were drawn by femoral venipuncture and anticoagulated with EDTA for morphological studies; sera for serologic studies were removed from clotted blood and stored in aliquots at −70°C until they were analyzed. Duplicate thick- and thin-smear preparations were prepared by conventional methods: thick smears were stained with Giemsa stain, and thin smears were stained with Giemsa and/or Wright stain. Examination for intraerythrocytic parasites was performed by bright-field examination at ×1,000 magnification, and the percentage of parasite-infected erythrocytes was determined (25). Thick smears were examined for a minimum of 10 min, and thin smears were examined for 15 to 20 min.

Parasite characterization by serologic methods.

Air-dried blood smears from the index case were forwarded to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (Don Knowles), Pullman, Wash., for examination with fluorescein-tagged monoclonal antibodies raised against Babesia bovis, Babesia equi, Babesia caballi, and Babesia bigemina in a direct fluorescent-antibody assay. Sera from six smear-positive and six smear-negative baboons were forwarded to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Marianna Wilson) for analysis of reactivity against B. microti antigens in an indirect immunofluorescent assay (IFA) (4). Additional sera were tested for reactivity to the antigen of WA-1, also in an IFA, at the University of California, Davis (Patricia Conrad) (36).

Genomic DNA preparation and amplification of nss rDNA.

Whole-blood DNA from a baboon chronically infected with E. macaci was extracted with the Isoquick DNA extraction kit (Orca Research Inc., Bothell, Wash.). The precipitated DNA was resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0 (100× stock from Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Piroplasm-specific DNA was amplified with 18sA and 18sC universal primers, which are directed against highly conserved portions of the eukaryotic nuclear small-subunit ribosomal DNA (nss rDNA) and which have been used successfully to detect other Babesia-like DNA sequences, such as WA1 (5, 29, 39). Five microliters of extracted DNA was used in a 50-μl PCR mixture. The reaction mixture contained 10 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.001% gelatin, 200 mM (each) deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 10% glycerol (Sigma), 0.5% Tween 20 (Sigma), 0.25 U of Ampli-Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer/Roche, Branchburg, N.J.), and 50 pmol of each of the primers. Amplification and subsequent isolation and visualization of the PCR product were performed as described previously (5).

Direct sequencing of PCR products.

PCR products were prepared for sequencing as previously described (17). Five hundred base pairs of the PCR product were directly sequenced multiple times with both of the PCR primers (18sA and 18sC) and internally located piroplasm consensus sequence primers. Sequencing was performed with a model 373 or 377 automated DNA sequencing instrument (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems Division, Foster City, Calif.). Overlapping sequences were aligned with Assemblylign sequence assembly software (Oxford Molecular, Campbell, Calif.) to generate a contiguous consensus sequence.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The contiguous consensus sequence obtained for the baboon babesial species was used as data input to search the GenBank sequence database, using the FASTA algorithm (11) to find related sequences. B. bovis (accession no. L19077), Babesia canis (L19079), B. divergens (U16370), B. equi (Z15105), Babesia gibsoni (L13729), B. microti (U09833), Babesia rodhaini (M87565), Theileria annulata (M64243), Theileria buffeli (Z15106), Theileria parva (AF013418), Theileria sergenti (AB000271), Theileria taurotragi (L19082), and WA1 (L13730) were used in the alignment. The sequences were aligned by using the Pileup program of the Wisconsin package (11). Phylogenetic analysis of the alignment was performed as described previously (17) with the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis program, version 1.01 (20), to make a Jukes-Cantor distance measurement and perform a neighbor-joining analysis with 500 bootstrap replicates. The Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony program, version 3.1.1 (38), was used to confirm the order observed by the neighbor-joining analysis (using a branch-and-bound algorithm with 100 bootstrap replicates).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The recovered partial nss rDNA sequence has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF081465 (Babesia sp. strain PB-1 from P. cynocephalus).

RESULTS

Morphological characterization.

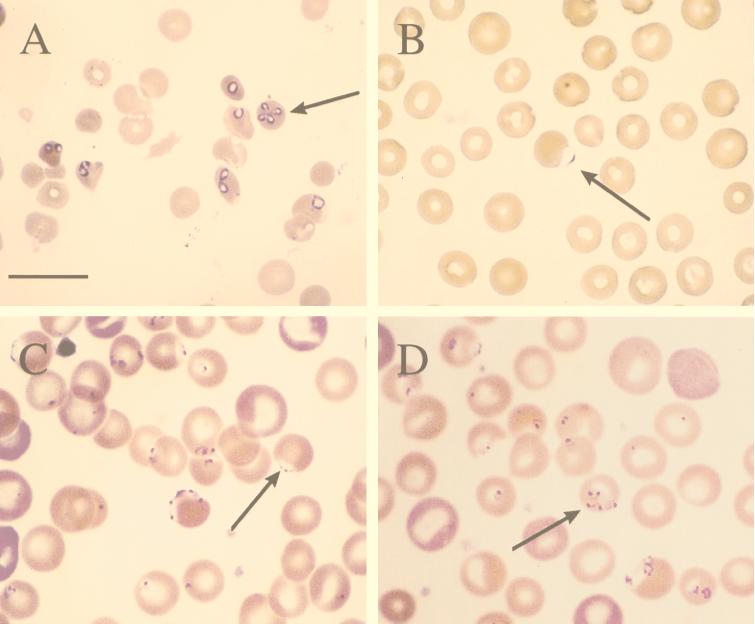

In the acute clinical infection seen during hemolytic crisis, we observed numerous intraerythrocytic ring-shaped and pyriform trophozoites; merozoites forming pairs and tetrads, the latter displaying occasional Maltese cross arrangements; and multiple infections of single erythrocytes (Fig. 1A). Individual trophozoites measured on average 1.8 × 3.5 μm and contained a small, dense chromatin mass usually oriented toward the pointed end. Hemoglobin breakdown products were not present, and the host erythrocyte was not stippled or enlarged. Greater than 50% of erythrocytes were parasitized by the seventh day following the onset of acute hemolytic crisis, and extracellular forms were frequently seen. Morphologically, this parasite resembled a typical Babesia sp. organism and was consistent with a description in older literature of Babesia pithici, a species found infecting cercopithicine monkeys and baboons (Table 1) (34). Whether the parasitemia represented recrudescence of a preexisting infection or was acquired via transfusion from the known positive animal could not be determined.

FIG. 1.

(A) Giemsa-stained thin blood film from an immunosuppressed baboon in severe hemolytic crisis secondary to fulminant Babesia infection. Note the presence of single intracellular ring-shaped trophozoites, typical piroplasms, and merozoites forming a tetrad or Maltese cross (arrow); (B) Giemsa-stained thin blood film of a healthy baboon displaying very rare accolé forms (arrow) consistent with E. macaci; (C and D) Wright’s-stained thin blood film from a baboon which had undergone splenectomy 30 days previously and had developed spontaneous parasitemia with E. macaci. Numerous delicate ring trophozoites, accolé forms (arrow in panel C), a tetrad (arrow in panel D), and erythrocytes containing multiple forms are seen. Bar = 12 μm.

TABLE 1.

Described species of piroplasms found naturally infecting nonhuman primates

| Species of parasite | Host species | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Babesia cheirogalei | Cheirogaleus major | 33 |

| Babesia galagolata | Galago crassicaudatus | 6 |

| Babesia perodictici | Perodicticus potto | 41 |

| Babesia pitheci | Cercopithecus, Cercocebus, and Papio spp. | 33, 34 |

| Babesia propitheci | Propithecus verreauxi | 40 |

| Babesia sp. | Macaca fuscata | 26 |

| Entopolypoides macaci | Macaca, Cercopithecus, and Papio spp. | 13, 23, 24 |

Blood smears from chronically infected but otherwise healthy-appearing baboons, including the blood donor, contained very rare parasites which were variable in appearance. The most difficult form to identify, due to its rarity and small size, was a delicate trophozoite consisting of a small dense chromatin dot attached to a small amount of bluish cytoplasm which resembled the shape of a parachute and which occupied <5% of the erythrocyte. These were most commonly found upon thorough evaluation of thick-smear preparations. Small intracellular rings with up to three chromatin bodies were also noted on some thin smears, plus rare accolé forms which had the appearance of large, pale-blue vesicles on the surface of the erythrocyte and which superficially resembled the accolé forms of Plasmodium falciparum (Fig. 1B).

One baboon, which had undergone splenectomy 4 weeks previously as part of another study, developed a spontaneous parasitemia that reached 30% at one point. A greater variety of morphological forms was detectable than that seen in the nonsplenectomized baboons, and these included variably sized ring forms, single trophozoites with two or more chromatin dots, tetrads, accolé forms, and extracellular parasites; some erythrocytes were infected with multiple stages of the parasite (Fig. 1C and D). Throughout the course of this recrudescence, the animal displayed no overt ill effects, although it became profoundly anemic and displayed clinical pallor. The variety of parasitic forms seen among the one splenectomized baboon and the other chronically infected baboons was most consistent with that described for E. macaci, reported to naturally infect Macaca irus, Macaca mulatta, Macaca fascicularis, Cercopithecus spp., and P. cynocephalus (8, 12, 13, 23, 24, 26).

Prevalence studies.

Blood smear examination of 65 animals revealed an overall infection prevalence with E. macaci of 31%: 30% (9 of 23) of animals born at the breeding facility at Medical Lake were positive; 35% (9 of 26) of animals shipped to the RPRC in Seattle from Southwest Foundation, and which were not held in the breeding facility at Medical Lake, were positive; and 12% (2 of 16) of the animals imported from Africa were positive. Thirteen of these 16 African animals originated from Ethiopia, all of which were smear negative; while records are incomplete, at least one of the 2 positive animals originating from Africa came from a supplier in Kenya.

Serologic characterization.

Blood smears from the index case were tested with fluorescein-labelled species-specific monoclonal antibodies directed against bovine (B. bovis and B. bigemina) and equine (B. equi and B. caballi) species of Babesia in a direct immunofluorescence procedure; no positive reactions were observed. Sera from six baboons positive by thick- and/or thin-smear examination and six smear-negative baboons were tested against B. microti antigen in an IFA: all reactions were negative, although sera from two smear-positive baboons gave titers of 1:16, which were considered to be inconclusive. The presence of this equivocal reactivity could not be correlated with the degree of parasitemia due to the rarity of parasites seen in blood smears. IFA of sera from smear-positive baboons with antigen of strain WA-1 was also negative.

Analysis of nss rDNA sequences.

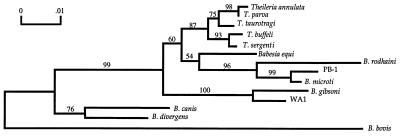

Phylogenetic analyses were performed on sequences obtained from the nss rDNA segments amplified by PCR from baboon blood samples. The region chosen for these analyses was an ∼500-bp 5′ portion of the nss rDNA determined previously to contain both alignable well-conserved regions and variable regions, and it was consequently considered to be an appropriate representative sequence (7, 29). Thirteen other related sequences were included in the analyses as listed in Materials and Methods. B. bovis, B. canis, and B. divergens are more distantly related and were used as outgroups (Fig. 2). The analyses indicate that PB-1 (for Papio-Babesia-1) is most closely related to B. microti (97.9% sequence similarity). Both the neighbor-joining and branch-and-bound parsimony analyses supported the clustering of PB-1 and B. microti in most of the bootstrap replicates (99 and 96%, respectively). Both analyses also supported the branch order shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Neighbor-joining analysis showing evolutionary relationships of 13 Babesia and Theileria species with PB-1; B. bovis, B. canis, and B. divergens represent outgroups. PB-1 appears to be most closely related to B. microti, with a sequence similarity of 97.9%. The percentages of 500 bootstrap replications in which designated groupings of species appeared are noted above the branches.

DISCUSSION

An incidental finding of lethal babesiosis in two immunocompromised baboons led to the discovery of enzootic chronic babesiosis in feral baboons of African origin and in baboons born and raised in two breeding colonies maintained in North America. The recognition of this parasitic infection raised questions as to the nature of the etiologic agent, origin, mechanism(s) of transmission, prevalence, and significance to animal and, possibly, human health. Based on the phylogenetic, serologic, and epidemiological studies presented here, and on a review of pertinent literature, we suggest that the genus Entopolypoides is synonymous with that of Babesia and that the morphological variations seen are occurring within a single species as a function of changes in host immune status.

Among described genera of apicomplexan hematozoa known to infect nonhuman primates (Plasmodium, Hepatocystis, Entopolypoides, and Babesia), morphological characteristics of the organisms seen in smears from two baboons which experienced fulminant hemolytic crises secondary to induced immunosuppression are typical for members of the genus Babesia (33). While reference was made by Ross in 1905 to the presence of B. pithici in Cercopithecus and Cercocebus monkeys and baboons, no further reports of babesiosis naturally occurring in baboons have been made, making the status of this species uncertain (34).

Unlike the typical babesial pyriforms seen during acute infection, blood stage forms seen in chronically infected, but otherwise healthy, baboons were significantly similar to the published descriptions of E. macaci. This species was originally described as a Babesia-like parasite from M. irus monkeys in Java but differed from typical Babesia spp. by consisting of small rings and amoeboid forms and by lacking the common occurrence of pyriform trophozoites (23). Hawking found a similar Entopolypoides parasite in a high proportion of Cercopithecus primates of African origin held at the Delta Regional Primate Research Center in Covington, La., and carefully described a variety of morphological forms which encompasses those we have seen in both acutely and chronically infected baboons (13). Subsequently, Kuntz and Moore found feral baboons in Kenya infected with a small, intraerythrocytic parasite which they also called E. macaci (21). In most naturally occurring Entopolypoides infections, parasitemias remained low and pathogenic effects were slight or unnoticeable unless the animal had undergone splenectomy, in which case high parasitemias usually did result but, again, with few apparent side effects (8, 12, 13, 16, 24). These published clinical observations of African and Asian primates closely parallel our experiences with baboon infections. Two cases of human infection with Entopolypoides spp. have also been reported, with both individuals suffering from hepatic dysfunction and one from asplenia, conditions known to predispose to severe piroplasmosis (42). This is of particular interest should these parasites be related to the Babesia spp. present in baboons.

On the basis of published biological, clinical, and morphological similarities between Babesia spp. and Entopolypoides spp., the taxonomic validity of the latter has been questioned, with Levine speculating that the two are synonymous (12, 13, 22). The data we present in support of synonymy comes from several sources. Clinically, the high prevalence of asymptomatic infection seen in colony baboons along with recrudescence following immunosuppression appears to be typical of natural infection with E. macaci in macaques, cercopithicine monkeys, and baboons. Most importantly, the phylogenetic analysis of a ribosomal gene sequence of Entopolypoides parasites recovered from the blood of a chronically infected baboon has been shown to be closely related to those of other species of Babesia, and specifically to B. microti (Fig. 2). Furthermore, sera from acutely and chronically infected baboons all reacted strongly in an IFA to the antigen harvested from the peripheral blood of a splenectomized baboon chronically infected with E. macaci, suggesting that the two morphological forms are the same, or closely related, antigenically (1, 3). While the variety of morphological forms of piroplasms seen in blood from acutely and chronically infected baboons thus appears to represent one species, whether they represent the previously described species, B. pithici and E. macaci, respectively, cannot be readily answered due to insufficient published information.

Additional analyses of phylogenetically meaningful molecules (e.g., nss rDNA) of Entopolypoides parasites known to infect macaques, Cercopithecus monkeys, and humans and their comparison with the PB-1 sequence would prove especially helpful in clarifying whether these parasites are identical to each other and to PB-1 or whether they represent different species. The use of such phylogenetic studies has been an important adjunct in the understanding of human infections caused by different species in the family Babesiidae; morphological analyses alone appear to be incapable of making such distinctions (14, 15, 18, 19, 28–30, 39).

The finding of 31% of baboons overall infected with PB-1 on the basis of blood smear evaluations and the presence of the parasite in animals born and raised in three different geographic locations, including 12% of those directly imported from Africa, points to the origin of the parasite in the animals’ ancestral homelands, with continued, effective, transmission occurring in breeding colonies in North America. This is consistent with the findings of Moore and Kuntz, who found 13% of baboons surveyed in central Kenya positive for E. macaci (24). While this preliminary epidemiological data does not permit us to more specifically address what mechanisms of transmission may be involved, either horizontal (mechanical or vectoral) transmission, vertical (maternal-fetal) transmission, or a combination of the two is possible. In all described life cycles of Babesia and Theileria spp., transmission is nominally accomplished through the bite of an appropriate, infected tick vector. While tick transmission is undoubtedly involved in the animals’ natural habitats, the geographic distances between the two U.S. breeding facilities, differences in local tick vectors, absence of ticks or other ectoparasites on any animal, and the continuous indoor caging of some animals suggest that additional mechanisms of transmission should be considered. Congenitally acquired infections are known to occur with some Babesia spp. infecting equine and human hosts (9, 43). E. macaci has also been detected in five baby baboons born to dams imported to the United States from Kenya, supporting the concept of vertical transmission as an epidemiological component of the infection (24).

The rarity of trophozoites in the peripheral blood of otherwise healthy baboons demonstrated that estimation of the prevalence of PB-1 infection based upon thick- and thin-smear evaluations may grossly underestimate the actual prevalence of infection in colony animals; the incidental finding of babesial recrudescence in immunosuppressed baboons further confirmed the presence of latent babesiosis. The lack of clinical symptoms and rarity of parasitemia in many B. microti-seropositive humans in areas of endemicity suggest that serologic assays may be a more accurate indicator of infection than smear evaluation (4, 18, 30, 31). Molecular methods of detection have also demonstrated that piroplasm-specific DNA may be recovered from individuals with previously unrecognized infection, revealing that a chronic carrier state, previously described in animals, may occur in humans as well (18, 29, 35). Considering this likelihood, we are currently investigating the use of a serologic assay as a more sensitive indicator for detecting Babesia infections in baboons (1, 3). The use of such an assay will be important in the management of our baboon breeding colony and may also provide additional epidemiological data from which mechanisms of transmission may be inferred and, ultimately, proven.

The finding of an animal model of babesiosis which, through experimental manipulation, closely mimics acute and chronic babesiosis in humans may offer unique opportunities to study pathophysiology, diagnostic approaches, therapeutic interventions, and the clinical outcomes of interactions with other simultaneously transmitted tick pathogens (e.g., Borrelia burgdorferi and Ehrlichia spp.) (19, 27). Also, the enzooticity of babesiosis in baboons and its phylogenetic similarity to B. microti, a recognized human pathogen, mandates screening of donor animals prior to xenotransplantation to prevent the accidental introduction of a potentially lethal blood parasite into an immunocompromised host (10).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Marianna Wilson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.; Patricia Conrad, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis; and David Knowles, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Pullman, Wash., for performance of the serologic studies described here. We also thank Dane Mathiesen for technical assistance and Chris Kolbert for analysis of sequence data.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants RR00166, AI41103-01, and AI35191.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldridge, K., and M. Bronsdon. Unpublished data.

- 2.Andrews R G, Bryant E M, Bartelmez S H, Muirhead D Y, Knitter G H, Bensinger W, Strong D M, Bernstein I D. CD34+ marrow cells, devoid of T and B lymphocytes, reconstitute stable lymphopoiesis and myelopoiesis in lethally irradiated allogeneic baboons. Blood. 1992;80:1693–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bronsdon M, Fritsche T R, Andrews R G, Bielitzki J T. Abstracts of the 92nd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1992. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. Detection of subclinical piroplasmosis in baboons (Papio sp.) by IFA, abstr. C-457; p. 496. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chisolm E S, Sulzer A J, Ruebush T K., II Indirect immunofluorescence test for human Babesia microti infection: antigenic specificity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35:921–925. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrad P A, Thomford J W, Marsh A, Telford III S R, Anderson J F, Spielman A, Sabin E A, Yamane I, Persing D H. Ribosomal DNA probe for differentiation of Babesia microti and B. gibsoni isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1210–1215. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1210-1215.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennig H K. Babesia galagolata n. sp., eine babesienart des galagos (Galago crassicaudatus) Z Parasitenkd. 1973;41:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis J, Hefford C, Baverstock P R, Dalrymple B P, Johnson A M. Ribosomal DNA sequence comparison of Babesia and Theileria. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emerson C L, Tsai C C, Holland C J, Ralston P, Diluzio M E. Recrudescence of Entopolypoides macaci Mayer, 1933 (Babesiidae) infection secondary to stress in long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Lab Anim Sci. 1990;40:169–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esernio-Jenssen D, Scimeca P G, Benach J L, Tenenbaum M J. Transplacental/perinatal babesiosis. J Pediatr. 1987;110:570–572. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox J L. Researchers consider cellular, solid-organ xenografts. ASM News. 1995;61:453–456. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genetics Computer Group. Program manual for the Wisconsin package. 8th ed. Madison, Wis: Genetics Computer Group; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleason N N, Wolf R E. Entopolypoides macaci (Babesiidae) in Macaca mulatta. J Parasitol. 1974;60:844–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawking F. Entopolypoides macaci, a Babesia-like parasite in Cercopithecus monkeys. Parasitology. 1972;65:89–109. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000044267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herwaldt B L, Persing D H, Precigout E A, Goff W L, Mathiesen D A, Taylor P W, Eberhard M L, Gorenflot A F. A fatal case of babesiosis in Missouri: identification of another piroplasm that infects humans. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:643–650. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-7-199604010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herwaldt B L, Springs F E, Roberts P P, Eberhard M L, Case K, Persing D H, Agger W A. Babesiosis in Wisconsin: a potentially fatal disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:146–151. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaschula V R, van Dellen A F, de Vos V. Some infectious diseases of wild vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops pygerythrus) in South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1978;49:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolbert C P, Bruinsma E S, Abdulkarim A S, Hofmeister E K, Tompkins R B, Telford III S R, Mitchell P D, Adams-Stich J, Persing D H. Characterization of an immunoreactive protein from the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1172–1178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1172-1178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause P J, Spielman A, Telford III S R, Sikand V K, McKay K, Christianson D, Pollack R J, Brassard P, Magera J, Ryan R, Persing D H. Persistent parasitemia after acute babesiosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:160–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807163390304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause P J, Telford S R, Speilman A, Sikand V, Ryan R, Christianson D, Burke G, Brassard P, Pollack R, Peck J, Persing D H. Concurrent Lyme disease and babesiosis: evidence for increased severity and duration of illness. JAMA. 1996;275:1657–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetic analysis, 1.01 ed. University Park: Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuntz R E, Moore J A. Commensals and parasites of African baboons (Papio cynocephalus L. 1766) captured in Rift Valley Province of Central Kenya. J Med Primatol. 1973;2:236–241. doi: 10.1159/000460326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine N D. The protozoan phylum Apicomplexa. II. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1988. p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer M. Uber einen neuen Blutparasiten des Affen (Entopolypoides macaci) Arch Schiffsu Tropenhyg. 1933;37:504. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore J A, Kuntz R E. Entopolypoides macaci Mayer, 1934 in the African baboon (Papio cynocephalus L. 1766) J Med Primatol. 1975;4:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000459826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Slide preparation and staining of blood films for the laboratory diagnosis of parasitic diseases. Tentative guideline M15-T. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otsuru M, Sekikawa H. Surveys of simian malaria in Japan. Zentbl Bakteriol Orig A. 1979;244:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persing D H. The cold zone: a curious convergence of tick-transmitted diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(Suppl. 1):S35–S42. doi: 10.1086/516170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persing D H, Conrad P A. Babesiosis: new insights from phylogenetic analysis. Infect Agents Dis Rev. 1995;4:182–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persing D H, Herwaldt B L, Glaser C, Lane R S, Thomford J W, Mathiesen D, Krause P J, Phillip D F, Conrad P A. Infection with a Babesia-like organism in Northern California. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:298–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502023320504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persing D H, Mathiesen D, Marshall W F, Telford S R, Speilman A, Thomford J W, Conrad P A. Detection of Babesia microti by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2097–2103. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2097-2103.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popovsky A M, Lindberg L E, Syrek A L, Page P L. Prevalence of Babesia antibody in a selected blood donor population. Transfusion. 1988;28:59–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1988.28188127955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quick R E, Herwaldt B L, Thomford J W, Garnett M E, Eberhard M L, Wilson M, Spach D H, Dickerson J W, Telford S R, Steingart K R, Pollock R, Persing D H, Kobayashi J M, Juranek D D, Conrad P A. Babesiosis in Washington State: a new species of Babesia? Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:284–290. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ristic M, Lewis G E. Babesia in man and wild and laboratory-adapted mammals. In: Kreier J, editor. Parasitic protozoa. IV. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross P H. A note on the natural occurrence of piroplasmosis in the monkey (Cercopithecus) J Hyg. 1905;5:18–23. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruebush T K, II, Collins W E, Warren M. Experimental Babesia microti infections in Macaca mulatta: recurrent parasitemia before and after splenectomy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:304–307. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruebush T K, II, Juranek D D, Chisholm E S, Snow P C, Healy G R, Sulzer A J. Human babesiosis on Nantucket Island: evidence for self-limited and subclinical infections. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:825–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197710132971511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shih C M, Liu L P, Chung W C, Ong S J, Wang C C. Human babesiosis in Taiwan: asymptomatic infection with a Babesia microti-like organism in a Taiwanese woman. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:450–454. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.450-454.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swofford D L. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony, 3.1.1 ed. Champaign, Ill: Illinois Natural History Survey; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomford J W, Conrad P A, Telford S R, Mathiesen D, Bowman B H, Spielman A, Eberhard M L, Herwaldt B L, Quick R E, Persing D H. Cultivation and phylogenetic characterization of a newly recognized human pathogenic protozoan. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1050–1056. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uilenberg G, Blancou J, Andrianjafy G. Un nouvel hematozoaire d’un Lemurien Malgache Babesia propitheci sp. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1972;47:1–4. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1972471001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van den Berghe L, Pell E, Chardome M. Un parasite sanguin du genre piroplasme chez un prosimien Perodicticus potto ibeanus au Congo belge. Folia Sci Afr Cent Bukavu. 1957;2:16. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf R E, Gleason N N, Schoenbaum S C, Western K A, Klein C A, Jr, Healy G R. Intraerythrocytic parasitosis in humans with Entopolypoides species (family Babesiidae). Association with hepatic dysfunction and serum factors inhibiting lymphocyte response to phytohemagglutinin. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:769–773. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-6-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young A S. Epidemiology of babesiosis. In: Ristic M, editor. Babesiosis of domestic animals and man. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]