Abstract

Introduction

Many adults, adolescents and children are suffering from persistent stress symptoms in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aims to characterize long-term trajectories of mental health and to reduce the transition to manifest mental disorders by means of a stepped care program for indicated prevention.

Methods and analysis

Using a prospective-longitudinal design, we will assess the mental strain of the pandemic using the Patient Health Questionnaire, Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire and Spence Child Anxiety Scale. Hair samples will be collected to assess cortisol as a biological stress marker of the previous months. Additionally, we will implement a stepped-care program with online- and face-to-face-interventions for adults, adolescents, and children. After that we will assess long-term trajectories of mental health at 6, 12, and 24 months follow-up. The primary outcome will be psychological distress (depression, anxiety and somatoform symptoms). Data will be analyzed with general linear model and machine learning. This study will contribute to the understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. The evaluation of the stepped-care program and longitudinal investigation will inform clinicians and mental health stakeholders on populations at risk, disease trajectories and the sufficiency of indicated prevention to ameliorate the mental strain of the pandemic.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (no. 2020-35).

Trial registration number

DRKS00023220.

Keywords: COVID-19, Stepped-care, Prediction, Family transmission, Cortisol

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a challenge for health care services around the world. Following the virus crisis, experts and scientists expect a mental health crisis (Wang et al., 2021). Psychological distress during this pandemic and in the aftermath may result from many sources such as threat to physical health, restricted social interactions and restricted civil rights, long crisis duration, unpredictability of its course and high economic uncertainty. We aim to identify individuals at risk, support those who show pronounced psychological distress with indicated prevention and observe their mental health trajectories up to 24 months.

1.1. Acute and prolonged effects of the pandemic on mental health

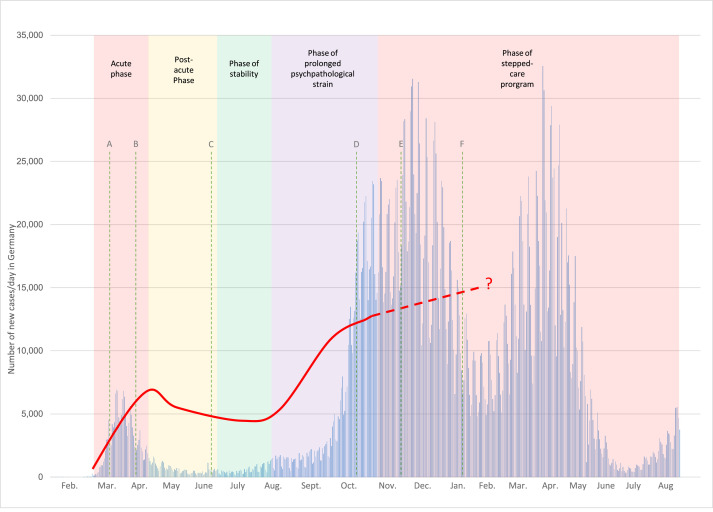

Several reviews, covering data from different countries around the world (China, Spain, Italy, Iran, the US, Turkey, Nepal, Denmark, and Germany), report a significant increase of anxiety, depression, psychological distress and sleeping problems in the acute response to the current pandemic (Bohlken et al., 2020; Liu & Heinz, 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Salari et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020). Single studies report comparable incidences between the lock-down in Germany (April 24 to May 23, 2020) and the year 2018 in a longitudinal investigation (Kuehner et al., 2020). Quarantine is associated with acute stress symptoms, fatigue, anxiety, sleeplessness, concentration problems, increasing avoidance and depressive symptoms which persist up to three years in both adults (Abad et al., 2010; Brooks et al., 2020; Hossain et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2012) and children (Loades et al., 2020; Saurabh & Ranjan, 2020). Evidence from other traumatic and catastrophic events does, however, suggest a delayed onset of psychopathology beyond the acute time of the lockdown (Meewisse et al., 2011). Such a delayed increase in the incidence of mental disorders has been commonly observed following previous community disasters (Lee et al., 2007; Yip et al., 2010; Boscarino, 2015; Katz et al., 2002; North, 2014). Due to the longer “incubation time” of mental disorders, we have to anticipate an incidence increase in the course of this pandemic (e.g. several months or even years after its onset – see Fig. 1), depending on the still unpredictable course of the pandemic. Economic consequences will increase financial strains on the long-term (Li & Mutchler, 2020). A rise in suicides must be anticipated because increased suicide rates have been demonstrated during previous financial crises (Reeves et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

The red line shows the assumed increase in psychological strain based on the increase in COVID-19 cases against distinct phases of the pandemic: an acute phase with mostly rising numbers, a post-acute phase of decreasing numbers and relaxation of restrictions and an intermediate phase of stability followed by a prolonged phase of stress and a second acute phase with rising numbers. The increase has been reported in preliminary studies, while a decrease will occur much later (Zielsek & Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, 2020).

Note. Numbers based on John Hopkins University, CDC, WHO; worldometers.info;

A – 22nd March: Strict limitations to leave the house, social distancing rules (green dotted line);

B – 20th April: First relaxation of restrictions, first implementation of mandatory face masks;

C – End of June: Several federal states allow regular service in kindergartens and schools;

D – 14th October: New restrictions for regions with more than 50 new infections per 100.000 inhabitants;

E – 28th October: Federal State and States of Germany decide on “part-lockdown”;

F – 10th January: Federal State and States of Germany decide on “lockdown”;

1.2. Framing the pandemic in terms of the diathesis-stress model

Diathesis-stress models focus on the importance of prolonged and extensive stress in interaction with predisposing factors conferring vulnerability for the development of psychopathology (e.g., Braet et al., 2013; McKeever & Huff, 2003). As the COVID-19 pandemic is a chronic stressor that affects entire societies globally, the psychological consequences can be expected to be large-scale. Following the diathesis-stress model we need to identify predisposing and event-related risk factors. The pandemic will affect multiple levels of stress-responsiveness, including biological stress axes such as the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system with its primary effector cortisol (McEwen, 2000). While a swift stress response is highly adaptive, chronic stress yields a variety of negative effects, including a well-known association with psychopathology (Aguilera, 2011). Measuring cortisol from hair has been established as a valid, reliable and relatively robust index of long-term cortisol levels (Stalder & Kirschbaum, 2012). A recent meta-analysis established an association of hair cortisol and adverse life events (Khoury et al., 2019). Interestingly, hair cortisol seems to be not linearly correlated to perceived stress (Stalder et al., 2017), emphasizing its potential as an objective biomarker of the body's stress response that is complementary, instead of redundant, to established psychosocial risk-factors for psychopathology. Research on predisposing individual and event-related risk factors affecting mental health following pandemics or disasters is scarce and mostly limited to cross-sectional studies. Young age, low formal education, female sex, being a parent, pre-existing mental disorders and working in health care are risk factors for developing psychopathology in the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Bohlken et al., 2020; Liu & Heinz, 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Salari et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020). Anxiety to be infected, frustration and boredom are further risk factors (Qiu et al., 2020). Event-related factors in former disasters include the duration of quarantine, supply/financial difficulties, and a lack of information (Abad et al., 2010; Brooks et al., 2020; Hossain et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2012; Loades et al., 2020). In addition, protective factors such as social support and access to (mental) healthcare have been restricted in the acute phase of the lockdown. The uncontrollability and unpredictability of the prolonged stress around the COVID-19 pandemic does not end abruptly but rather fades into post-stress coping.

1.3. Ameliorating long-term trajectories of psychopathology by indicated prevention

Therefore, we urgently need a resource-efficient approach to mental health care using low-threshold, easily accessible and distributable interventions (de Girolamo et al., 2020; North & Pfefferbaum, 2013; Shore et al., 2020; Torous & Wykes, 2020). Digital mental health approaches are particularly feasible to reach many people at low threshold, especially in times of social distancing (Balcombe & De Leo, 2020; Bucci et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2020). Both disasters and isolation lead to an increase of psychopathology such as anxiety, depression, distress, and sleeping problems. Although spontaneous remission over time can be expected to some extent (Jeong et al., 2016; North & Pfefferbaum, 2013), several risk factors might predict a maladaptive course over time (Jeong et al., 2016). For example, a large impairment through the virus and the restrictions in everyday life or a history of mental disorders might obstruct spontaneous remission. The transition from the acute to the prolonged phase of this pandemic thus opens a window of opportunity to apply programs of indicated prevention to alleviate the long-term burden on mental health. Knowledge about risk factors for a maladaptive cause of mental health problems allows the early identification of individuals at-risk who should be addressed. Indicated prevention offers the advantage to specifically focus on individuals at risk (e.g. with persistent, yet subclinical stress symptoms) and may help to reduce the burden of new incident mental disorders by interrupting the transition from sub- to suprathreshold mental problems. Several studies investigating effects of indicated prevention demonstrated the benefit of online-delivered and face-to-face interventions. Especially cognitions associated with anxiety disorders and depression were significantly reduced after indicated prevention (Kenardy et al., 2006; Stockings et al., 2016). As individuals at risk will present with different trajectories of response towards psychological aid, stepped-care programs represent an adaptive solution. Stepped care offers low-threshold programs for a broad population, followed by more intensive care for those not initially responding. Supporting a stepped care model, Ehlers and colleagues demonstrated the efficiency of a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) based indicated prevention to prevent the onset of post-traumatic stress disorder following car accidents (Ehlers et al., 2003). In their randomized controlled trial, a group of patients with early PTSD symptoms who were unlikely to recover without intervention were identified. Stepped care was provided with self-help booklets as the low-level intervention and CBT as high-level intervention.

1.4. An intergenerational perspective of families regarding psychopathology and treatment

Next to focusing on the individual and its trajectory over time, assessment of families provides the unique possibility to study upward spirals into increasing mental health strain of both child and parent (Hill et al., 2011; Middeldorp et al., 2016; Orvaschel et al., 1988) and downward spirals releasing mental health burden in one party if the other is treated (e.g., Schneider et al., 2013). Psychopathology runs in families (e.g. Cheung & Theule, 2016; Wesseldijk et al., 2018) and increases perceived stress in the family (e.g. Tan & Rey, 2005; Weijers et al., 2018). Additionally, interactional vicious circles of family conflict and psychopathology increase family stress (Hill et al., 2011; Middeldorp et al., 2016; Orvaschel et al., 1988). A study targeting post-disaster effects showed that parents reporting probable post-traumatic stress disorder after a tornado also reported a greater frequency of children with borderline or abnormal difficulties (Houston et al., 2015). Similarly, in an Indonesian post-earthquake sample, parents’ posttraumatic symptoms were associated with children's general distress (Juth et al., 2015). However, children's posttraumatic symptoms were not associated with parents’ general distress which might point to a stronger directionality from parent to child. Further, among school children aged 7 to 11 years, exposure to mass trauma (i.e., civil war and a tsunami) and family violence were significant risk factors of child mental health while parental care emerged as a significant protective factor (Sriskandarajah et al., 2015). Thus, parent characteristics and familial relations – either functional or dysfunctional – are directly related to child mental health. We will therefore examine carry-over effects within the family against the background of the current pandemic by specifically addressing families.

1.5. Study aims and hypotheses

As the COVID-19 pandemic acts as a chronic global stressor, a rise in new-incident mental disorders must be anticipated. We assume adults, children and families will be negatively affected in different ways depending on several risk and protective factors. The longer incubation time of mental disorders will however lead to a delayed onset of new-incident cases. This delay offers a window of opportunity to implement preventive measures right now in order to reduce the burden on mental health. As pointed out, stepped-care programs utilizing digital mental health applications are ideally suited to meet specific features of this pandemic (e.g. low-threshold psychological aid accessible for large parts of the population without the need for personal interaction).

By implementing an indicated prevention program using a stepped-care approach and conducting a long-term observation we aim to:

-

(1)

Analyze who is particularly at risk for adverse outcomes in the short term based on subjective data and cortisol levels (subsequently referred to as research question 1).

-

(2)

Investigate individual trajectories of long-term effects during the next two years (research question 2).

-

(3)

Study familial carry-over effects of both psychopathology and psychopathology relief due to psychological interventions on parents and children based on family relations (research question 3).

We hypothesize that psychological distress in the prolonged phase of the pandemic is associated with initial high stress levels (cortisol), pre-existing psychopathology, and more exposure to adverse experiences in the acute phase, low social support, and low coping abilities. Second, we hypothesize that we can predict outcomes following the interventions and at follow up based on baseline information. Social support and coping strategies are expected to be most predictive. Third, we hypothesise to find a moderation of the relationship between child and parent psychopathology by family stress. Additionally, we assume to observe a carry-over effect of decreasing psychological stress from parent to child by participating in the preventive intervention.

2. Methods and analysis

2.1. Study design

This study is a prospective longitudinal investigation employing a stepped-care approach for indicated prevention targeting psychological distress because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on ethical considerations to provide low-threshold and instant support on the one hand, and our research focus – risk factors, long-term trajectories and carry-over effects – on the other hand, no randomization to a control condition is conducted. Instead, a within-subject waiting period preceding the face-to-face intervention is realized.

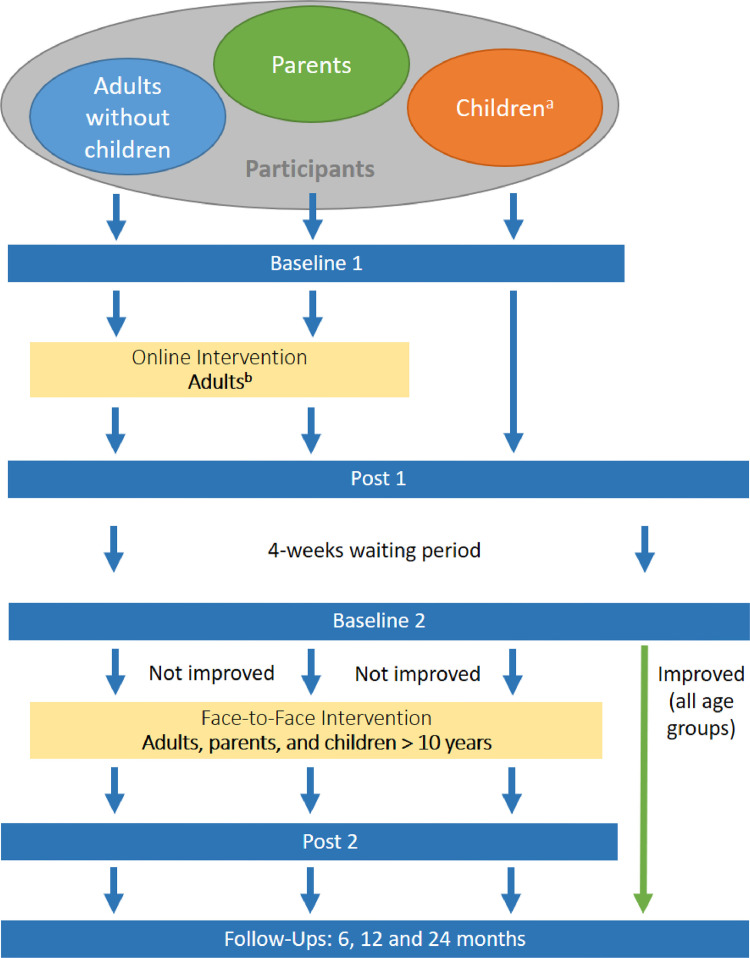

The assessment consists of seven time points (see Fig. 2). The first (pre-online; baseline 1) and second (post-online; post 1) time points are conducted before and after an online intervention (step 1 of stepped-care program). After a 4-week waiting period, the third (pre-face-to-face; baseline 2) and fourth (post-face-to-face; post 2) time points are conducted before and after a face-to-face group intervention (step 2 of stepped-care program). Three follow-up assessments (6-, 12- and 24months; follow-up 1, 2 and 3) are conducted. The assessments are conducted separately for adults reporting their own mental health only (subsequently referred to as adults) and adults with children reporting on both their own mental health, family strain and their children's mental health (parents). Parents decide if they want to focus on their own stress or on one of their children's strain. Further, youth (11-17 years) can also self-report on their mental strain.

Fig. 2.

Procedure shows sample and subsamples in circles, assessment time points as blue bars and intervention steps as yellow bars.

a Children participate in self-assessment if > 10 years old. bChildren may participate while the intervention is targeted at adults.

2.2. Sample characteristics and recruitment pathway

Inclusion criteria for step 1 (online intervention) are being able to consent and the age of 11 years or older (youth, parent, or adult). Inclusion criteria for step 2 (face-to-face group intervention) are being able to consent and the age of 11 years or older (child, youth, parent or adult), and either significant psychopathology or subjective need for a face-to-face intervention quoted by participants themselves. Significant psychopathology is defined as follows: adults at least above one cut-off (>10) of the somatic, anxiety, or depressive subscales of the Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., 2001, 2002, 2010; Körber et al., 2011); children at least above one cut-off of the Patient Health Questionnaire – Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-9 A; Richardson et al., 2010a), the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Woerner et al., 2004, Woerner et al., 2004) or Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS, Spence et al., 2003). For behavioral irregularities, the SDQ's subscales behavioural disorder, hyperactivity and prosocial behavior are referred to for inclusion (see Woerner et al., 2004). For anxiety, reference scores of the SCAS are used depending on gender and age (Boys up to 11 years ≥ 20, Boys 12 years and older ≥ 16; Girls up to 11 years ≥25; Girls 12 years and older ≥ 20). Exclusion criteria are age below 5 and indication of an inpatient treatment setting (i.e., acute psychosis, suicidality etc.). For the face-to-face intervention, participants are excluded if they either report low psychopathology levels or no wish for continuing treatment. Participants are recruited via local and nationwide press, flyers, social media, psychotherapy outpatient centers, and medical practices in Berlin. Participants had to speak German.

Sample size calculation. Previous studies on the effect of preventive interventions show small to medium effect sizes (e.g. Stockings et al., 2016). Based on a power calculation, we conservatively assumed a small effect (f= 0.15), alpha-error = 0.05, and a statistical power of 80%. Using the Software G-Power (Faul et al., 2007), hypothesis 1 will be analyzed using a multiple regression analysis resulting in a required sample size of n= 92. For hypothesis 2, classical power analyses to estimate the minimum sample size needed are unavailable for machine learning. However, previous investigations seem to indicate that for many datasets and algorithms learning rates and confidence intervals reach a plateau between 200 and 400 samples (Figueroa et al., 2012). This includes participants at baseline, who do not necessarily require the face-to-face intervention. Hypothesis 3 will be analyzed using a moderator analysis and ANOVAs with repeated measures which resulted in a maximum required sample size of n= 90 parents, and n = 90 children. To confront possible drop-out, we are aiming at including n= 99 participants per group (adults, families). In sum, we are including at minimum n = 400 participants at baseline and at least n= 198 participants (including dropouts) in the face-to-face intervention.

2.3. Assessments

Participants retrospectively report on adverse experiences during the first wave of the pandemic (in Germany ca. Chancellor Angela Merkel's “address to the nation” on March 18 until Whitsunday holidays when a considerable set of restrictions were suspended). Additionally, we assess psychological distress in the prolonged phase, i.e. the time following the relaxation of social distancing restrictions. All participants are encouraged to send in a hair strand to assess hair cortisol as a biological stress marker. We conduct seven assessments as indicated in Fig. 2. Data collection (via https://www.limesurvey.org/) began on September 1th, 2020 and lasts until around August 2023, including all follow-up assessments. Parents need to decide if they want to participate alone or with a child. If parents choose to include one of their children, they have to fill out two surveys in case the child of interest is 5–10 years old – one about themselves and another one about the mental health of the children they want to report on. Children aged 11 to 17 years can report on their mental health themselves. Still, the participation of a parent is mandatory. Tables 1 and 2 list the assessment instruments.

Table 1.

Overview of assessments for adults.

| baseline 1 | post 1 | baseline 2 | post 2 | follow-ups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | x | ||||

| COVID-19 Questionnaire | x | x | x | x | |

| ERQ | x | ||||

| PHQ-D version C | x | x | x | x | x |

| SF-8 | x | x | x | x | x |

| SCID-Screening | x | ||||

| ASI-3 | x | x | x | ||

| PTQ | x | x | x | ||

| ISI | x | x | x | ||

| Haircortisol | x |

ERQ: Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-8: Short-form 8 Health Survey; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview based on DSM-5 (checking for exclusion criteria); ASI-3: Anxiety Sensitivity Questionnaire-3; PTQ: Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index

Table 2.

Overview of assessments for parents and children.

| Parent | Child 11-17 years | Baseline 1 | Post 1 | Baseline 2 | Post 2 | Follow-ups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | x | x | x | ||||

| COVID-19 Questionnaire | x | x | x | x | x | X | |

| PHQ-9 A | x | x | x | x | x | x | X |

| SDQ | x | x | x | x | x | x | X |

| SCAS | x | x | x | x | x | x | X |

| Sleep | x | x | x | x | x | x | X |

| QoL | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| ERQ-C | x | x | x | ||||

| FRKJ | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| PTQ | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| CCNES | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| PDTS | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| PS | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| DIPS-Screening | x | x | |||||

| Haircortisol | x | x | x |

PHQ-9 A: Patient Health Questionnaire Adolescent; SDQ - Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SCAS - Spence Child Anxiety Scale (short version), QoL – Quality of Life, ERQ-K: Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (child version), FRKJ - Fragebogen zu Ressourcen im Kindes- und Jugendalter (Questionnaire for resources in childhood and youth); PTQ: Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire; CCNES - Coping with the Child's Negative Emotions Scale (short version); PS - Parenting Scale (short version); PTDS – Parental Distress Tolerance Scale (short version); DIPS - Diagnostic interview for mental disorders in children

Sociodemographic variables. Standard sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, education) are assessed.

Quality of life. Quality of life is assessed with specific questionnaires for adults with 8 items (SF-8; Ware et al., 2001) and children with 10 items (KIDSCREEN-10, Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010) regarding satisfaction with mental and physical wellbeing. Both questionnaires show good psychometric properties (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Ware et al., 2001).

Events related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on considerations about distress concerning different topics affected by the crisis including physical and mental health, social isolation and contact restrictions, infections or deaths in the family, financial burdens, burden due to home office and home schooling, we developed assessments for adults, parents (regarding their child), and children. Patients have to answer 35 items covering event-related stress based on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from not at all to a lot/very much) or with yes or no.

Psychopathology assessment primary outcome measures—adults. As a primary outcome, we use a German translation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-D version C) as a dimensional (severity of symptoms) and categorical (cut-offs for a clinically relevant syndrome) measure of psychopathology. The version C of the PHQ-D is an established instrument with three subscales (9 items for depressive symptoms – PHQ 9, 13 items for somatic symptoms – PHQ 15 and 7 items for anxiety/panic symptoms – GAD 7) and good psychometric properties (Gräfe et al., 2004; Spitzer et al., 2006; Kroenke et al., 2001, 2002).

Psychopathology assessment primary outcome measures—children. An adolescent version of one scale of the PHQ assesses depressive symptoms on 9 items covering the last two weeks and asking for personal impairment on a 4-point scale (Richardson et al. 2010a). Additionally, subscales for the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Woerner et al., 2004) assess hyperactivity, conduct problems, and prosocial behaviour in 15 items using a 3-point scale. Finally, a short version (Ahlen et al., 2018) of the Spence Child Anxiety Scale (Spence et al., 2003) covers anxiety symptoms using 19 items and a 4-point Likert scale. Both parents (children aged 5 to 17) and youths (aged 11–17) report on all symptoms. All questionnaires show good psychometric properties (Richardson et al. 2010a; Woerner et al., 2004; Ahlen et al., 2018; Spence et al., 2003) and serve as both, dimensional (severity of symptoms) and categorical (cut-offs for a disorder) measure of psychopathology.

Psychopathology assessment secondary outcome measures—adults. Sleeping problems are assessed with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI 7 items - Gregory et al., 2011). Additionally, the Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ 15 items - Ehring et al., 2011) and anxiety sensitivity with the Anxiety Sensitivity Inventory (ASI 18 items - Reiss et al., 1986) are assessed. All questionnaires show good psychometric properties (Ehring et al., 2011; Gregory et al., 2011; Reiss et al., 1986).

Psychopathology assessment secondary outcome measures—children and families. We adapted the adult version of the PTQ (Ehring et al., 2011) asking youth to self-report about perseverative thinking. Sleeping problems were assessed using the corresponding subscale (6 items) of the Child Behavior Checklist (cf. Gregory et al., 2011). Youths (aged 11–17 years) report on both PTQ and sleeping problems, while parents (children aged 5 to 17 years) only report on child sleeping problems. All questionnaires show good psychometric properties (Ehring et al., 2011; Gregory et al., 2011).

Family stress. An abbreviation of the Parental Distress Tolerance Scale as advised by the original authors (personal communication; Debener et al., 2020) is used to assess parenting stress on 13 items using a 5-point Likert scale. Negative parenting behavior is covered by a short version of the Parenting Scale (PS; Arnold et al., 1993) using 13 items which are answered each on a bipolar scale. Finally, the Coping with the Child's Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES; Fabes et al., 2002) assesses parental reactions towards their child in emotionally challenging situations. Due to length restrictions, only the nonsupportive subscales minimizing and punitive reactions are used leading to 18 items and asking to rate the probability of use on a 7-point Likert scale. Youths (aged 11–17 years) complete only the CCNES, while parents (children aged 5 to 17 years) complete on all family stress questionnaires. All questionnaires show good psychometric properties (Debener et al., 2020; Arnold et al., 1993; Fabes et al., 2002)

Coping. Emotion regulation as a type of coping is assessed using separate questionnaires for children (Gullone & Taffe, 2012) and adults (Gross & John, 2003). It assesses the strategies reappraisal (6 items) and suppression (4 items) asking how much the items apply on a 7-point Likert Scale. In youths (aged 11–17 years), we additionally assess resources (Fragebogen zu Ressourcen im Kindes- und Jugendalter [FRKJ], Lohaus & Nussbeck, 2016) covering individual and social resources. All questionnaires show good psychometric properties (Gullone & Taffe, 2012; Gross & John, 2003; Lohaus & Nussbeck, 2016).

Biological stress marker hair cortisol. This prolonged exposure to stress places the body's stress response and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis in the spotlight. Representing a “diary” of stress events for the previous couple of months, hair cortisol is a particularly suitable and easy to collect biomarker that allows giving an estimate of the amount of reactivity towards the current pandemic situation (Russell et al., 2012). For the assessment of hair cortisol, hair strands are taken closely to the scalp from a posterior vertex position during the first baseline assessment. If possible, 6cm of hair are taken in order to assess cortisol secretion over the last 6 months given an average hair growth rate of 1 cm per month (Wennig, 2000; Stalder & Kirschbaum 2012). An established liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry protocol is implemented to measure hair cortisol (Vogeser & Parhofer, 2007).

Documentation of intervention completion, dose and adherence. For the online intervention as the first step in our stepped-care program we collect data on dosage. We keep track of the number of logins and the number of modules completed. For the face-to-face intervention, we collect data on completion and ensure adherence. We keep track of the number of sessions a participant attends. For adherence, all clinicians offering groups were trained in the standardized manual used for the intervention and attended weekly supervision with the project managers.

2.4. Stepped-care program

In the stepped-care program, participants are offered a low-threshold online intervention first. Second, a group-based face-to-face intervention is offered to those who still present with residual symptoms (see Section 2.2).

The online intervention is based on the digital consultant Aury (developed in cooperation with the company “Mental Tech GmbH”) and is based on general CBT principles (psychoeducation, cognitive and behavioural exercises). Aury works via an algorithm-based chatbot (short dialogues with some interaction). The content is realized as 24 short modules (i.e., –three modules each for sleeping problems, rumination, conflicts, depressive symptoms, anxiety, resources) lasting approx. 5–10 min, and 6 longer modules that can be individualized to a specific problem the participant would like to work on. The later follow the principles of solution-based short-term therapy (Franklin et al., 2012). Participants can freely choose the order of topics as well as the number of modules they wish to complete. As such, the program can be personalized to a certain extent. Aury can be used at no charge for a time interval of 4 weeks user data will be extracted to quantify the dose and content of treatments requested. Via https://aury.co/ the online intervention is available free of charge. Everyone can start or, after attending in our study, restart the intervention here.

The manualized face-to-face intervention offers higher treatment intensity including more opportunity to practice. It consists of 6 (adults) or 7 (parents, children) weekly 100 min face-to-face group interventions, respectively. Group size is 10 participants. Parents and children are separated. Contents of the face-to-face intervention parallel the online intervention (i.e., sleeping problems, rumination, conflicts, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and resources) for both adults and children. The intervention for parents of younger children (5–10 years) differs slightly in organization and content (i.e., add-on: parenting strategies). Adults in the adult condition are offered the possibility to participate in two optional sessions on trauma and parenting. All sessions are based on CBT methods (psychoeducation, model deduction, techniques for behaviour modification, work sheets for exercises at home). Additionally, all participants are instructed to learn progressive muscle relaxation based on Jacobson (1938) as a relaxation technique, which is instructed in each session and provided as an exercise at home. After the group intervention is completed, all participants receive the opportunity for an individual closing meeting at the outpatient clinic which can be used for a more thorough diagnostic and individual psychotherapy initiation if still necessary. Increasing cases of COVID-19 and more restrictions in the second lockdown forced us to change the setting. We now conduct the face-to-face intervention online, while content and dosage stay the same.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Hypothesis 1 (risk factors for current psychopathology) will be investigated with a cross-sectional analysis based on baseline 1 information. A psychopathology composite score serves as an estimate of current psychopathology via the sum of all sub scores of the corresponding questionnaires. Multiple hierarchical linear regression analysis will use the psychopathology composite score as criterion. Centered predictors will be included in a theory-driven hierarchical fashion, i.e. starting with (1) pre-existing high stress levels (cortisol) followed by (2) pre-existing psychopathology, and (3) potential factors around the acute stress phase, i.e. more exposure to adverse experiences, low social support, low coping abilities. Hypothesis 2 (individual trajectories at follow-up assessments) will be investigated by a machine learning approach. Psychological and stress-related biomarkers will be sampled at Baseline 1. Post-online- intervention, post-group- intervention and 24 months FU will be used as endpoints. Post-intervention predictions will only use baseline information as predictors, while 24 months FU predictions will be done once using baseline information only and once using an enhanced predictor set including intervention information (such as participation in the face-to-face group intervention). Adequate feature selection methods such as elastic net will be used and model hyperparameters will be tuned with an internal cross-validation loop. As outcomes we will employ the binary decision whether a subject is under or above any PHQ cut-off score at each time-point specified above. We will evaluate prediction performance using metrics such as area-under-the-curve, balanced accuracy, sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, we will examine model calibration. Classifier weights will be used to evaluate the relative importance of predictor variables included in the final model. Hypothesis 3 (expected carry-over effects) is based on a moderator analysis targeting only measures from pre-online (baseline 1) assessment with parent psychopathology as independent and child psychopathology as dependent variable will be conducted including both family stress and resources as moderators. An ANOVA with repeated measures over 2 measurements (pre-online and post-online) will compare child psychopathology composite scores before and after parental online intervention. Correlational analyses will test whether a decrease in child psychopathology (differential scores between pre-face-to-face and pre-online, resp.) is positively correlated with amount of parental intervention. Further, an ANOVA with repeated measures over 2 measurements (pre-face-to-face, post-face-to-face) will test for a decrease in parental psychopathology before and after child or parent face-to-face intervention. Finally, two ANOVAs with repeated measures will target a decrease in family stress levels (parenting stress, negative parenting behaviour) and an increase in child resources comparing levels before (pre-face-to-face) and post intervention (post-face-to-face).

3. Discussion and outlook

For the COVID-19 pandemic, the lack of available resources in mental healthcare is critical, and we implemented several measures to optimize their efficient use. However, maximizing the gain from these resources is an issue that points far beyond COVID-19, as mental health resources have long been scarce. In 2010 22.4 % of the global burden years lived with disability were due to mental and behavioural disorders (Vos et al., 2012). Still, a report by the Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health (2018) stated "All countries can be thought of as developing countries in the context of mental health” (Patel et al., 2018). The treatment gap for mental disorders – the difference between the needed and provided care – is supposed to be the biggest compared to other health sectors (Trautmann et al., 2016). In Germany, as an example of a high-income country, in 2018 the average waiting period to start an outpatient psychotherapy treatment was 19.9 weeks (Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer, 2018).

We implement several approaches to increase the efficiency of resources. Studies of randomized trials and national health projects like the “Improving Access to Psychological Treatment” initiative in England demonstrated the feasibility and resource- and cost-effectiveness of stepped care programs as primary care and prevention (Clark, 2011; Radhakrishnan et al., 2013; Van't Veer-Tazelaar et al., 2010). In addition to that, meta-analyses that demonstrate the effectiveness of digital mental health interventions especially in anxiety, depression and insomnia also call for studies investigating the feasibility of digital mental health interventions in real life environments (Adults: Ebert et al., 2015, 2017, 2018; Venkatesan et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2010b; Children and adolescents: Hollis et al., 2017). Repeatedly, digital mental health solutions were demanded to support those suffering from anxiety, depression, psychological distress and sleeping problems in the acute response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Bohlken et al., 2020; Liu & Heinz, 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Salari et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Xiang et al., 2020). Therefore, our study is meeting more than current demanding's. It fits in the situation in mental health care in general.

Precision medicine individualizes treatment by interventions tailored to individual patient characteristics. Approaching this goal, machine learning has been applied to determine psychotherapy treatment outcomes for individual patients (e.g. Hilbert et al., 2020) or to determine individual treatment recommendations (e.g. Deisenhofer et al., 2018, Schwartz et al., 2020, Delgadillo et al., 2020; Cohen et al., 2020). Many predictive models are still in a proof-of-concept phase but may be able to provide clinical benefit to patients in the future. Here, we aim to complement existing work on treatment for full-blown mental disorders with the prediction of individual trajectories in indicated prevention. In the future, prediction of such individual treatment trajectories may help to allocate limited resources only to those individuals with the highest need.

Finally, the treatment and analysis of both children's and parents’ psychopathology will allow the examination of carry-over effects of both psychopathology (Hill et al., 2011; Middeldorp et al., 2016; Orvaschel et al., 1988) and treatment effects (e.g., Schneider et al., 2013). Potentially, this allows a decrease of psychopathology symptoms in several family members by only treating one person. However, mediating factors (e.g., family stress) need to be further examined to identify potential impediments.

Put together, by implementing a stepped-care program, a scalable digital mental health intervention, the prediction of individual trajectories and a family perspective on treatment, this study will not only facilitate public mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic, but also concerns the efficient use of limited resources in mental healthcare in general. The follow up investigation will inform clinicians and mental health stakeholders on populations at risk, long-term disease trajectories and the effectiveness of psychological aid via indicated prevention to ameliorate the mental strain of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Till Langhammer: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Kevin Hilbert: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Berit Praxl: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Clemens Kirschbaum: Project administration. Andrea Ertle: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Julia Asbrand: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Ulrike Lueken: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

This paper and the research behind it would not be possible without the exceptional support of Robert Wasenmüller, Sophia Seemann and Laurenz Endl. Robert Wasenmüller is responsible for technical support of the digital intervention. Sophia Seemann and Laurenz Endl are assisting the data acqusistion.

References

- Abad C., Fearday A., Safdar N. Adverse effects of isolation in hospitalised patients: A systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2010;76(2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera G. HPA axis responsiveness to stress: Implications for healthy aging. Experimental Gerontology. 2011;46(2–3):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlen J., Vigerland S., Ghaderi A. Development of the Spence children's anxiety scale—Short version (SCAS-S) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2018;40(2):288–304. doi: 10.1007/s10862-017-9637-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D.S., O'Leary S.G., Wolff L.S., Acker M.M. The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(2):137–144. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balcombe L., De Leo D. An integrated blueprint for digital mental health services amidst COVID-19. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7(7):e21718. doi: 10.2196/21718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlken J., Schömig F., Lemke M.R., Pumberger M., Riedel-Heller S.G. COVID-19-pandemie: Belastungen des medizinischen personals: Ein kurzer aktueller review. Psychiatrische Praxis. 2020;47(04):190–197. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino J.A. Community disasters, psychological trauma, and crisis intervention. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience. 2015;17(1):369–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet C., Vlierberghe L.V., Vandevivere E., Theuwis L., Bosmans G. Depression in early, middle and late adolescence: Differential evidence for the cognitive diathesis–Stress model. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2013;20(5):369–383. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci S., Schwannauer M., Berry N. The digital revolution and its impact on mental health care. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2019;92(2):277–297. doi: 10.1111/papt.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer (2018). BPtK-studie zur reform der psychotherapie-richtlinie. Wartezeiten.

- Chang B.P., Kessler R.C., Pincus H.A., Nock M.K. Digital approaches for mental health in the age of COVID-19. BMJ. 2020:m2541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K., Theule J. Parental psychopathology in families of children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25(12):3451–3461. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0499-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D.M. Implementing NICE guidelines for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders: The IAPT experience. International Review of Psychiatry. 2011;23(4):318–327. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.606803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Z.D., Kim T.T., Van H.L., Dekker J.J.M., Driessen E. A demonstration of a multi-method variable selection approach for treatment selection: Recommending cognitive-behavioral versus psychodynamic therapy for mild to moderate adult depression. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. 2020;30(2):137–150. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2018.1563312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Girolamo G., Cerveri G., Clerici M., Monzani E., Spinogatti F., Starace F., Tura G., Vita A. Mental health in the coronavirus disease 2019 emergency—The Italian response. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debener, A., Cobham, V.E., & Heinrichs, N. (2020). The parental distress tolerance scale. Unpublished Questionnaire. A Joint Effort Supported by the TU Braunschweig, University of Queensland and University of Bremen.

- Deisenhofer A.K., Delgadillo J., Rubel J.A., Böhnke J.R., Zimmermann D., Schwartz B., Lutz W. Individual treatment selection for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2018;35(6):541–550. doi: 10.1002/da.22755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgadillo J., Gonzalez S., Duhne P. Targeted prescription of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus person-centered counseling for depression using a machine learning approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2020;88(1):14–24. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Van Daele T., Nordgreen T., Karekla M., Compare A., Zarbo C., Brugnera A., Øverland S., Trebbi G., Jensen K.L., Kaehlke F., Baumeister H. Internet- and mobile-based psychological interventions: Applications, efficacy, and potential for improving mental health. European Psychologist. 2018;23(2):167–187. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Cuijpers P., Muñoz R.F., Baumeister H. Prevention of mental health disorders using internet- and mobile-based interventions: A narrative review and recommendations for future research. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2017;8:116. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Zarski A.C., Christensen H., Stikkelbroek Y., Cuijpers P., Berking M., Riper H. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PloS ONE. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A., Clark D.M., Hackmann A., McManus F., Fennell M., Herbert C., Mayou R. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy, a self-help booklet, and repeated assessments as early interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1024–1032. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T., Zetsche U., Weidacker K., Wahl K., Schönfeld S., Ehlers A. The perseverative thinking questionnaire (PTQ): Validation of a content-independent measure of repetitive negative thinking. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2011;42(2):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes R.A., Poulin R.E., Eisenberg N., Madden-Derdich D.A. The coping with children's negative emotions scale (CCNES): Psychometric properties and relations with children's emotional competence. Marriage & Family Review. 2002;34(3–4):285–310. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Lang A.G., Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa R.L., Zeng-Treitler Q., Kandula S., Ngo L.H. Predicting sample size required for classification performance. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2012;12(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin C., Trepper T.S., McCollum E.E., Gingerich W.J. OUP USA; 2012. Solution-focused brief therapy: A handbook of evidence-based practice. [Google Scholar]

- Gräfe K., Zipfel S., Herzog W., Löwe B. Screening psychischer störungen mit dem “gesundheitsfragebogen für patienten (PHQ-D) Diagnostica. 2004;50(4):171–181. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924.50.4.171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A.M., Cousins J.C., Forbes E.E., Trubnick L., Ryan N.D., Axelson D.A., Birmaher B., Sadeh A., Dahl R.E. Sleep items in the child behavior checklist: A comparison with sleep diaries, actigraphy, and polysomnography. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(5):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J.J., John O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullone E., Taffe J. The emotion regulation questionnaire for children and adolescents (ERQ–CA): A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(2):409–417. doi: 10.1037/a0025777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert K., Kunas S.L., Lueken U., Kathmann N., Fydrich T., Fehm L. Predicting cognitive behavioral therapy outcome in the outpatient sector based on clinical routine data: A machine learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2020;124 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S.Y., Tessner K.D., McDermott M.D. Psychopathology in offspring from families of alcohol dependent female probands: A prospective study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45(3):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis C., Falconer C.J., Martin J.L., Whittington C., Stockton S., Glazebrook C., Davies E.B. Annual research review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems – A systematic and meta-review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2017;58(4):474–503. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.M., Sultana, A., & Purohit, N. (2020). Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: A systematic umbrella review of the global evidence (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3561265). Social Science Research Network. 10.2139/ssrn.3561265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Houston J.B., Spialek M.L., Stevens J., First J., Mieseler V.L., Pfefferbaum B. 2011 Joplin, Missouri Tornado experience, mental health reactions, and service utilization: Cross-sectional assessments at approximately 6 months and 2.5 years post-event. PLoS Currents. 2015;7 doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.18ca227647291525ce3415bec1406aa5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson E. 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press; 1938. Progressive relaxation; p. 494. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Yim H.W., Song Y.J., Ki M., Min J.A., Cho J., Chae J.H. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East respiratory syndrome. Epidemiology and Health. 2016;38 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juth V., Silver R.C., Seyle D.C., Widyatmoko C.S., Tan E.sT. Post-disaster mental health among parent–Child dyads after a major earthquake in Indonesia. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43(7):1309–1318. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz C.L., Pellegrino L., Pandya A., Ng A., DeLisi L.E. Research on psychiatric outcomes and interventions subsequent to disasters: A review of the literature. Psychiatry Research. 2002;110(3):201–217. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenardy J., McCafferty K., Rosa V. Internet-delivered indicated prevention for anxiety disorders: Six-month follow-up. Clinical Psychologist. 2006;10(1):39–42. doi: 10.1080/13284200500378746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury J.E., Bosquet Enlow M., Plamondon A., Lyons-Ruth K. The association between adversity and hair cortisol levels in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;103:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körber S., Frieser D., Steinbrecher N., Hiller W. Classification characteristics of the patient health questionnaire-15 for screening somatoform disorders in a primary care setting. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2011;71(3):142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(2):258–266. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehner C., Schultz K., Gass P., Meyer-Lindenberg A., Dreßing H. Psychisches befinden in der bevölkerung während der COVID-19-pandemie. Psychiatrische Praxis. 2020;47(07):361–369. doi: 10.1055/a-1222-9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.M., Wong J.G., McAlonan G.M., Cheung V., Cheung C., Sham P.C., Chu C.M., Wong P.C., Tsang K.W., Chua S.E. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52(4):233–240. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Mutchler J.E. Older adults and the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2020;32(4–5):477–487. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1773191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Heinz A. Cross-cultural validity of psychological distress measurement during the coronavirus pandemic. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1055/a-1190-5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Kakade M., Fuller C.J., Fan B., Fang Y., Kong J., Guan Z., Wu P. Depression after exposure to stressful events: Lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loades M.E., Chatburn E., Higson-Sweeney N., Reynolds S., Shafran R., Brigden A., Linney C., McManus M.N., Borwick C., Crawley E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohaus, A., & Nussbeck, F.W. (2016). Fragebogen zu Ressourcen im Kindes- und Jugendalter (FRKJ 8–16) | Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie | Vol 65, No 1. Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie. https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/abs/10.1024/1661-4747/a000302.

- McEwen B.S. Effects of adverse experiences for brain structure and function. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):721–731. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeever V.M., Huff M.E. A diathesis-stress model of posttraumatic stress disorder: Ecological, biological, and residual stress pathways. Review of General Psychology. 2003;7(3):237–250. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.7.3.237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meewisse M.L., Olff M., Kleber R., Kitchiner N.J., Gersons B.P.R. The course of mental health disorders after a disaster: Predictors and comorbidity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24(4):405–413. doi: 10.1002/jts.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp C.M., Wesseldijk L.W., Hudziak J.J., Verhulst F.C., Lindauer R.J.L., Dieleman G.C. Parents of children with psychopathology: Psychiatric problems and the association with their child's problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;25:919–927. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0813-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North C.S. Current research and recent breakthroughs on the mental health effects of disasters. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2014;16(10):481. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0481-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North C.S., Pfefferbaum B. Mental health response to community disasters: A systematic review. JAMA. 2013;310(5):507–518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.107799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H., Walsh-Allis G., Ye W.J. Psychopathology in children of parents with recurrent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;16(1):17–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00910497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Saxena S., Lund C., Thornicroft G., Baingana F., Bolton P., Chisholm D., Collins P.Y., Cooper J.L., Eaton J., Herrman H., Herzallah M.M., Huang Y., Jordans M.J.D., Kleinman A., Medina-Mora M.E., Morgan E., Niaz U., Omigbodun O., UnÜtzer Jü. The lancet commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1553–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan M., Hammond G., Jones P.B., Watson A., McMillan-Shields F., Lafortune L. Cost of improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) programme: An analysis of cost of session, treatment and recovery in selected primary care trusts in the East of England region. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer U., Erhart M., Rajmil L., Herdman M., Auquier P., Bruil J.…Kilroe J. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: A short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(10):1487–1500. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A., Stuckler D., McKee M., Gunnell D., Chang S.S., Basu S. Increase in state suicide rates in the USA during economic recession. The Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1813–1814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S., Peterson R.A., Gursky D.M., McNally R.J. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L.P., McCauley E., Grossman D.C., McCarty C.A., Richards J., Russo J.E., Rockhill C., Katon W. Evaluation of the patient health questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson T., Stallard P., Velleman S. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for the prevention and treatment of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13(3):275–290. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell E., Koren G., Rieder M., Van Uum S. Hair cortisol as a biological marker of chronic stress: Current status, future directions and unanswered questions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(5):589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor S., Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health. 2020;16(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh K., Ranjan S. Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S., In-Albon T., Nuendel B., Margraf J. Parental panic treatment reduces children's long-term psychopathology: A prospective longitudinal study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2013;82(5):346–348. doi: 10.1159/000350448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B., Cohen Z.D., Rubel J.A., Zimmermann D., Wittmann W.W., Lutz W. Personalized treatment selection in routine care: Integrating machine learning and statistical algorithms to recommend cognitive behavioral or psychodynamic therapy. Psychotherapy Research. 2020;0(0):1–19. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2020.1769219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore J.H., Schneck C.D., Mishkind M.C. Telepsychiatry and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic—Current and future outcomes of the rapid virtualization of psychiatric care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence S.H., Barrett P.M., Turner C.M. Psychometric properties of the Spence children's anxiety scale with young adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17(6):605–625. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriskandarajah V., Neuner F., Catani C. Parental care protects traumatized Sri Lankan children from internalizing behavior problems. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0583-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T., Kirschbaum C. Analysis of cortisol in hair – State of the art and future directions. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2012;26(7):1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T., Steudte-Schmiedgen S., Alexander N., Klucken T., Vater A., Wichmann S., Kirschbaum C., Miller R. Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;77:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockings E.A., Degenhardt L., Dobbins T., Lee Y.Y., Erskine H.E., Whiteford H.A., Patton G. Preventing depression and anxiety in young people: A review of the joint efficacy of universal, selective and indicated prevention. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46(1):11–26. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S., Rey J. Depression in the young, parental depression and parenting stress. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. 2005;13(1):76–79. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2004.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torous J., Wykes T. Opportunities from the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic for transforming psychiatric care with telehealth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann S., Rehm J., Wittchen H.-U. The economic costs of mental disorders. EMBO Reports. 2016;5 doi: 10.15252/embr.201642951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Veer-Tazelaar P., Smit F., van Hout H., van Oppen P., van der Horst H., Beekman A., van Marwijk H. Cost-effectiveness of a stepped care intervention to prevent depression and anxiety in late life: Randomised trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 2010;196(4):319–325. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.069617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan A., Rahimi L., Kaur M., Mosunic C. Digital cognitive behavior therapy intervention for depression and anxiety: Retrospective study. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7(8):e21304. doi: 10.2196/21304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeser M., Parhofer K. Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)—Technique and applications in endocrinology. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 2007;115(09):559–570. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T., Flaxman A.D., Naghavi M., Lozano R., Michaud C., Ezzati M., Shibuya K., Salomon J.A., Abdalla S., Aboyans V., Abraham J., Ackerman I., Aggarwal R., Ahn S.Y., Ali M.K., Alvarado M., Anderson H.R., Anderson L.M., Andrews K.G., Atkinson C., Memish Z.A. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. (London, England) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Di Y., Ye J., Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2021;26(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J., Kosinski, M., Dewey, J., Gandek, B., & Kisinski, M. (2001). How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: A manual for users of the SF-8™ Health Survey.

- Weijers D., van Steensel F.J.A., Bögels S.M. Associations between psychopathology in mothers, fathers and their children: A structural modeling approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018;27(6):1992–2003. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennig R. Potential problems with the interpretation of hair analysis results. Forensic Science International. 2000;107(1–3):5–12. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(99)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesseldijk L.W., Dieleman G.C., van Steensel F.J.A., Bartels M., Hudziak J.J., Lindauer R.J.L., Bögels S.M., Middeldorp C.M. Risk factors for parental psychopathology: A study in families with children or adolescents with psychopathology. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;27(12):1575–1584. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerner W., Becker A., Rothenberger A. Normative data and scale properties of the German parent SDQ. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;13(Suppl 2) doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-2002-6. II3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerner W., Fleitlich-Bilyk B., Martinussen R., Fletcher J., Cucchiaro G., Dalgalarrondo P., Lui M., Tannock R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire overseas: Evaluations and applications of the SDQ beyond Europe. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;13(2):ii47–ii54. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-2008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li D., Iacobucci M., Ho R., Majeed A., McIntyre R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y.T., Yang Y., Li W., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Cheung T., Ng C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):228–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip P.S.F., Cheung Y.T., Chau P.H., Law Y.W. The impact of epidemic outbreak: The case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2010;31(2):86–92. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielsek J., Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E. Deutsches Ärzteblatt; 2020. COVID-19-pandemie: Psychische Störungen werden zunehmen.https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/214303/COVID-19-Pandemie-Psychische-Stoerungen-werden-zunehmen June 10. [Google Scholar]