Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic presented many challenges for graduate medical education, including the need to quickly implement virtual residency interviews. We investigated how different programs approached these challenges to determine best practices.

Methods

Surveys to solicit perspectives of program directors, program coordinators, and chief residents regarding virtual interviews were designed through an iterative process by two child neurology residency program directors. Surveys were distributed by email in May 2021. Results were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Responses were received from 35 program directors and 34 program coordinators from 76 programs contacted. Compared with the 2019-2020 recruitment season, in 2020-2021, 14 of 35 programs received >10% more applications and most programs interviewed ≥12 applicants per position. Interview days were typically five to six hours long and were often coordinated with pediatrics interviews. Most programs (13/15) utilized virtual social events with residents, but these often did not allow residents to provide quality feedback about applicants. Program directors could adequately assess most applicant qualities but felt that virtual interviews limited their ability to assess applicants' interpersonal communication skills and to showcase special features of their programs. Most respondents felt that a combination of virtual and in-person interviewing should be utilized in the future.

Conclusions

Residency program directors perceived some negative impacts of virtual interviewing on their recruitment efforts but in general felt that virtual interviews adequately replaced in-person interviews for assessing applicants. Most programs felt that virtual interviewing should be utilized in the future.

Keywords: Virtual interviews, Residency application, Graduate medical education, Match, Survey

Introduction

The COVID-19 global pandemic presented a vast array of new challenges for graduate medical education. Among these was the need to quickly implement solely virtual residency interview experiences for the 2020-2021 recruitment season. With the help of graduate medical education (GME) planning within institutions and swift efforts conducted within professional organizations, the interview season proceeded with only a short delay in applications opening to programs for review. However, the impact of virtual recruitment and opportunities it represents are still being defined.

The child neurology recruitment process presents unique considerations for programs and applicants. Interviews must be coordinated between two and sometimes three departments—pediatrics, adult neurology, and child neurology. Applicants must consider their education during different phases of training. Additionally, quality of life factors related to a program's location and culture are increasingly important.1

Before COVID-19, there were some reports comparing in-person and virtual residency and fellowship interview experiences. Most of these studies were limited by occurring at a single institution and in a single—and often times procedural—specialty. But available data suggest that there is “universal gratitude” among applicants for having the option for virtual interviews.2 At the same time, 15% of applicants felt that a virtual format negatively impacted their self-presentation and 34% said that it negatively impacted their ranking of the program during a season in which they interviewed in-person at other programs.2 Interview format did not affect program ranking of applicants or match rate for anaesthesiology and ophthalmology,3 , 4 despite the perception at least within a cardiothoracic surgery fellowship, that it did.5

Students and residents in a variety of specialties prefer in-person interviews but still feel that virtual should be an option even if they themselves would not necessarily opt for it.6 Cost, travel distance, and time away from education are factors favoring virtual interviews, while the desire to interact directly with residents and faculty and to assess potential quality of life in a location are factors in favor of in-person interviews.6 Removing the barriers of in-person interviewing allows applicants to interview with more programs.3 , 7 But of applicants who completed a virtual interview, 17% still incurred the time and expense to travel to the city to visit informally before matching.4

There are advantages and disadvantages for programs too. Some programs felt that they were limited by the virtual format in showcasing their attributes.5 , 8 For example, it was difficult to adequately convey facilities through a virtual tour.5 Program directors often found it difficult to assess an applicant's “fit” for their program through virtual interviews.7 , 8 However, virtual interviews may require less faculty time than in-person interviews.2 The majority of applicants and program directors have a favorable view of continuing virtual interviews, at least in some capacity, when pandemic-related restrictions are lifted.5 , 8 , 9

We sought to better define the experience of child neurology residency programs with virtual interviews during the 2020-2021 residency recruitment season.

Methods

In May 2021, child neurology residency program directors (PDs), program coordinators (PCs), and chief residents (CRs) in the United States were recruited to participate. A list of programs and contact information was obtained from the Child Neurology Society website listing of Child Neurology Training Programs, and 76 child neurology program director–coordinator dyads were contacted through direct email. CRs were not contacted directly, but the invitation to PD/PCs contained a link for a separate resident survey to be distributed to any CRs who were involved in 2020-21 recruitment efforts.

The surveys were designed through an iterative process by the authors who are residency PDs, and draft versions were reviewed for clarity by multiple individuals. Different surveys were used for each group (Supplement). The surveys were administered through SurveyMonkey.com, a web-based application used for building and managing online surveys. A reminder email was sent 1 week and 3 weeks after the initial request. A small number of PD and/or PC email addresses were returned as undeliverable, and those individuals were not pursued further.

The surveys collected anonymous information about 2020-21 virtual recruitment including the size of program, number of applicants and interviewees, structure of the interview day, use of social media, effectiveness of the virtual format for assessing candidates, time requirements compared with in-person interviewing, and preferences for future recruitment (Supplemental Material). Each survey consisted of 10 questions, including multiple-choice, multiple-selection, and open-ended questions inviting narrative comments.

Results were summarized using descriptive statistics. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Rochester Medical Center and Nationwide Children's Hospital.

Results

We received responses from 35 PDs, 34 PCs, and 15 CRs of the 76 programs we attempted to contact, resulting in a response rate of 46% for PDs and 45% for PCs. Response rate for CRs could not be calculated as we could not control for the number of residents who received the survey invitation from their directors and/or coordinators. Additionally, PCs and PDs were not instructed to send the CR to a specific number of residents. CR respondents were more likely to be from larger programs than the other respondents (weighted average of 3.4 positions per program for CRs compared with 2.3 for PDs and PCs).

Numbers of applicants, interviewees, and ranked candidates

The numbers of positions offered in the 2020-2021 recruitment season compared with 2019-2020 were similar for our respondents, which is consistent with data reported by the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) with 159 categorical child neurology positions offered in 2020 and 2021.10 , 11 Categorical positions are ones that offer two years of pediatrics and three years of neurology training in the same institution. The majority of programs (71% of PD and PC respondents) were recruiting for either one or two categorical positions. The number of applications received was similar to that in the previous year for 19 of 35 programs; however, 14 reported receiving greater than 10% more applications, while only one program received more than 10% fewer applications. Increases in the number of applications received were seen by programs of all sizes, with seven of 25 programs recruiting for one to two positions and two of seven programs recruiting for at least four positions reporting an increase of more than 10% in applications received.

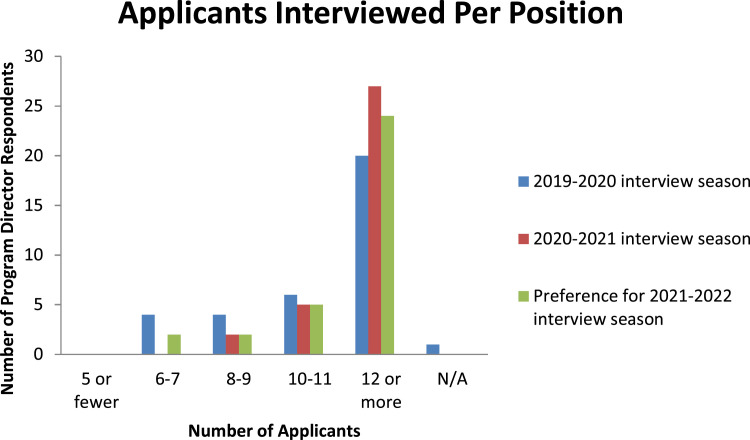

Responding programs tended to increase the number of interviews per position for the 2020-2021 recruitment season, with the majority interviewing at least 12 applicants per open position (Figure 1 ). The number of interviews per open position did not vary greatly with program size, with 85% of programs recruiting for 1-2 positions, and 80% of programs recruiting ≥4 positions interviewing ≥12 applicants per position. Applicant quality was similar to (n = 18) or better (n = 14) than previous years, according to PD respondents. None reported a decrease in applicant quality. PCs reported that 26% ranked ≥10% more applicants than the previous year.

FIGURE 1.

Number of applicants interviewed per positioned offered over the last two recruitment cycles, and preferences for the 2021-2020 interview season. The color version of this figure is available in the online edition.

Interview logistics and assessing applicants

PCs most often reported fewer cancelled interview appointments, and those that were cancelled were easier to fill than previous years. The interview days were coordinated with pediatrics interviews in 23 of 33 programs (either same day [18/33] or consecutive days [5/33]). The interview day contained a variety of activities, with the most common being an opportunity to meet residents (30/34) and a program overview presentation (28/34). Table specifies what types of live (synchronous) content were offered as described by PCs. Data extracted from narrative comments provided by 21 PCs indicated that the majority of interview days were single-day experiences (15/21) that ranged from <5 hours (four programs) to eight to nine hours (three programs), with a mode of five to six hours in a day (eight programs). On the other hand, six of 21 programs included multiday experiences that ranged from eight to 13 hours combined.

TABLE.

Content of Live (Synchronous) Recruitment Day Activities as Reported by Program Coordinators

| Live Activities Offered | # Of Programs Including (Total = 34) |

|---|---|

| Resident Meet & Greet | 30 |

| Orientation to the Program | 28 |

| Meeting/comments from Chair or Division Chief | 19 |

| Teaching Conference | 18 |

| Video tour prerecorded and presented with live comments | 14 |

Social events required significant coordination for the 2020-2021 interview season with reliance on platforms that were new for many programs. All but one chief resident reported resident participation in virtual social events, and most (13/15) felt that the quality of social interaction in a virtual platform was inferior to that of an in-person experience. CR comments indicated that it was difficult to have good conversations and get to know the applicants as well as showcase the city. However, smaller groups and breakout rooms seemed to be the most useful approach. Program participation in social media grew significantly between the 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 interview seasons (increased from five to 13 of the 15 programs with CR survey responses), and the majority of CRs (9/15) indicated that they had a major role in maintaining social media accounts. Despite heavy resident involvement, only two of 15 residents reported that they were able to provide quality feedback to their programs on applicants. One commented that they could provide feedback only on applicants who were clear outliers from the group, either positive or negative, and another commented that resident ability to get to know applicants improved over the season as they became more familiar with the process.

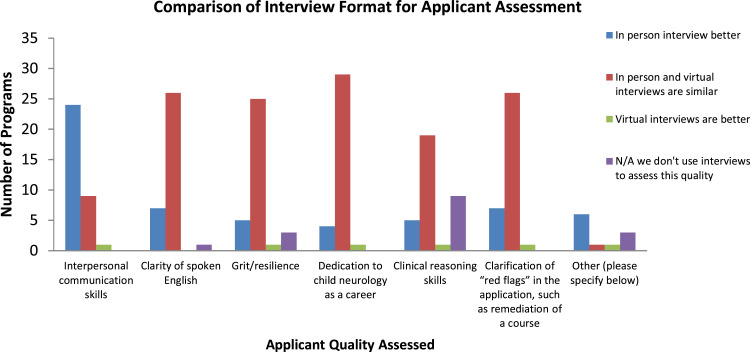

PDs were more likely to report use of standardized questions during interviews in 2020-2021 than in the previous year, but the majority of programs (20/35) did not use standardized questions. Most PDs felt that virtual and in-person interviews were similar for assessing most applicant qualities, with the exception of in-person interviews being better for assessing interpersonal communication skills (Figure 2 ). However, PDs felt that the most important quality to be gleaned from the interview was interpersonal communication skills, followed by interest/enthusiasm about the program and dedication to the field. The majority of PDs (25/34) felt that the virtual platform had a negative impact on their program's ability to highlight its unique qualities. Despite the impression of lower quality interview interactions in 2021, interviews were of similar importance in determining the rank list compared with previous years for the majority of programs (28/35).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of effectiveness of interview format in assessing applicant qualities. The color version of this figure is available in the online edition.

Future recruitment

CRs and PCs were more likely to predict that in-person interviewing in the future will require more of their time than virtual recruitment. PDs were more likely to predict that faculty time spent on recruitment would be similar regardless of format, although 14 of 34 still felt that in-person interviews would require more faculty time. Regardless of format, 73% of PDs and 82% of PCs planned to continue interviewing at least 12 applicants per position in the future.

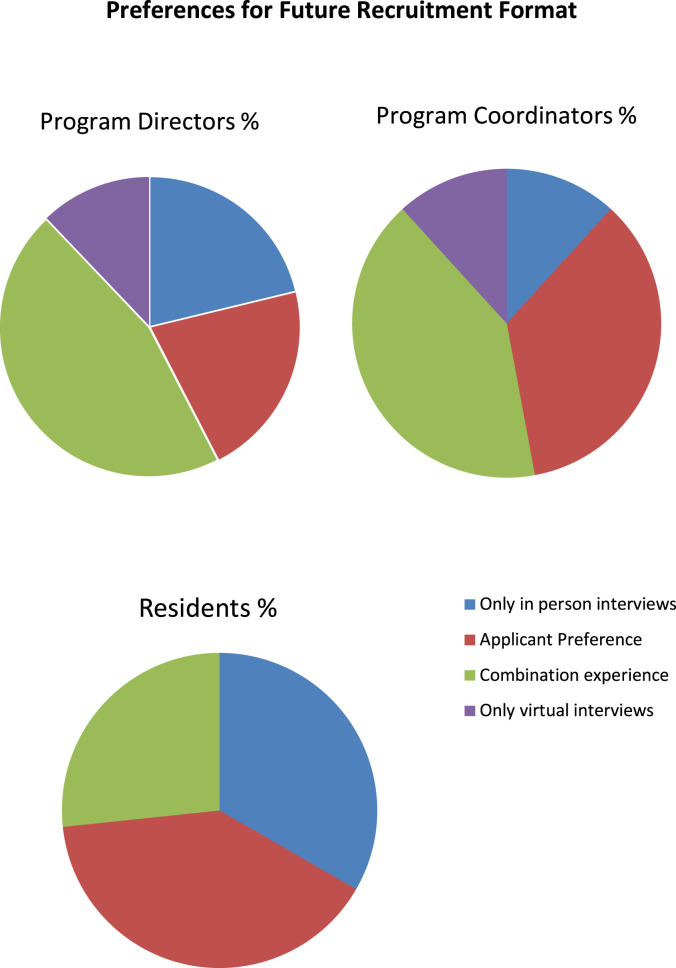

When asked about preferences for future recruitment formats, the majority of respondents in all groups recommended having a combination format in which individual applicants would have both virtual and in-person experiences (Figure 3 ). However, through free-text comments, all groups raised concerns about equity and judgment that would favor applicants who could visit the program in-person. Given this concern, respondents indicated the need for a uniform approach for all applicants. Several respondents suggested a virtual interview day followed by an in-person second visit that could be voluntary, conducted after rank lists are completed or completed in a manner that blinded program leadership from the identity of visiting applicants.

FIGURE 3.

Respondents preferences for format of future recruitment. The color version of this figure is available in the online edition.

Discussion

Match rate, application inflation, and interview trends

This study investigated the residency program perspective on virtual recruitment during the 2020-2021 recruitment cycle by surveying child neurology PDs, PCs, and CRs. With the change to virtual interviewing, there were many uncertainties faced by programs including (1) whether applicants would apply to more programs (thus necessitating interviewing more applicants), (2) the most ideal timing and components of the interview day including what content should be delivered live versus prerecorded, (3) what impact there would be on programs' and applicants' abilities to assess each other, and (4) how virtual components would be utilized in the future.

Among child neurology programs that responded to our survey, 40% saw a >10% increase in applications received. Because less than 3% of programs reported a 10% decrease in applications received, the findings suggest an overall increase in applications per program. The lack of extrinsic limitations on accepting interview offers, such as money and travel time, which is afforded by virtual interviews, likely contributed to the increase in applications.12 Likewise, programs increased the number of applicants they interviewed, with 82% interviewing ≥12 applicants per position.

While child neurology remains a small field, minor changes in application, interview, and ranking trends could have significant effects on programs. NRMP data indicate that the total applicants ranking child neurology positions in the 2021 and 2020 matches were 218 and 213, respectively.10 While the number of applicants increased by only five, the number of positions ranked by applicants increased from 1760 to 2109 between 2020 and 2021, which corresponds to an increase from 8.3 to 9.7 programs ranked per applicant, indicating that applicants ranked more positions.10 , 11 As a result, programs needed to rank an additional 1.9 applicants per position, or 7.9 applicants per position compared with 5.9 in 2020, to fill in 2021.10 , 11 The “application inflation” has been seen in other specialties including obstetrics, maternal fetal medicine, and dermatology7 , 8 , 12 and can disadvantage less competitive applicants, ultimately leading to more unfilled positions nationally.

Overall, 92.5% of categorical child neurology positions were filled in the main 2021 Match.10 This fill rate is lower than the 2021 fill rates for pediatrics and adult neurology positions which were 98.6% and 98.2%, respectively. The number of unfilled categorical child neurology residency positions increased from 8 in 2020 to 12 in 2021. But given that the 2021 child neurology fill rate was within the range of the last five years (91.7-96.2%), we cannot make conclusions about the presence or impact of application inflation on child neurology at this point in time.10 , 11

Increasing numbers of interviews are particularly challenging for child neurology residency because of the need to coordinate with pediatrics and, for some programs, adult neurology programs. Through our survey, we found a wide range in the length of interview days, and in how programs combined with pediatrics. The majority of programs had a combined, single interview day with pediatrics that was typically around 6 hours long. It may have been challenging for programs to provide enough content to effectively “sell” the program, while not requiring applicants to spend too much time sitting in front of their computer. Most programs included a synchronous (live) orientation and meetings with the residents, but less than half of programs included a live tour (or prerecorded tour with live comments).

Virtual communication and culture

Social interactions and the ability to convey quality of life and cultural aspects of a program and surrounding city are particularly challenging during a virtual interview experience, despite these factors being increasingly important to child neurology applicants.1 In our survey, the majority of residents felt that the virtual social events were not as high quality as past in-person events. Some commented that the sessions were more of an informal question-and-answer session than an opportunity to learn about one another. As such, the vast majority of CRs did not feel that they could provide quality feedback to programs about the applicants (13/15). The use of small breakout rooms seemed to be helpful, but overall, the quality of applicant-resident interactions was likely a major drawback to virtual interviewing for both programs and applicants.

As programs enter another season of virtual recruitment and consider the future use of virtual recruitment, it is important to consider the amount of time residents spend contributing to social media and other recruitment efforts, particularly if these will result in low-quality interactions with little value added to the program and resident educational experience. We did not quantify the presumed impact of social media on program advertising, but we did find that CRs were often asked to manage social media. One CR commented that the responsibility of keeping up the program's social media presence was “a lot of additional work.”

PDs generally felt that virtual interviews were comparable with in-person interactions for assessing most applicant qualities, with the exception of interpersonal communication skills, which were better assessed in-person. It is noteworthy that interpersonal communication skills were also the most important characteristic to be evaluated during an interview. The majority of PDs (25/34) also felt that it was harder for them to highlight unique aspects of their programs, which indicates that virtual interviewing seemed overall less effective than in-person. Thus, it is reasonable to infer that overall the interview process was negatively impacted by the virtual format.

Implications for future recruitment

Nationally, residency programs are struggling to determine the best recruitment strategy after pandemic restrictions are fully lifted. Our survey respondents seemed to favor a combination of both virtual interviews and in-person visits during the recruitment season. Through free-text comments, some respondents acknowledge that allowing applicants to choose either virtual or in-person interactions could lead to inequity because applicants from further away or with fewer resources are less likely to travel. As a result, a standardized experience that incorporates virtual interviews and removes any possible influence of in-person visits from a program's rank list may be able to maximize equity and flexibility for applicants while still allowing programs an opportunity to demonstrate their culture, facilities, and other unique aspects to interested applicants. Applicants could use the virtual interview to prioritize programs and allow them to concentrate their resources on visiting programs in which they have a genuine interest.

As long as there are minimal constraints on the number of interviews an applicant accepts, programs will likely face “application inflation.” Professional societies and medical schools could collaborate on how to advise medical students when planning their applications. Standards within fields could also be agreed upon by PD groups, as has been done with obstetrics where there is an agreed upon final application deadline, a standard 72 hours in which applicants have time to reply to interview offers and a deadline for programs to notify applicants of their status (interview/no interview/waitlist). A ticketing system through which applicants have a limit on the number of interviews they can accept, with an increased allowance for couples matching, has been proposed but not implemented.13 Such an interview cap could help candidates be more selective in their application process, improve the chances of less competitive applicants matching, and reduce some of the burden on programs. However, limiting applications also limits program exposure to applicants who might discover a great fit with a program they might not have considered had they been more selective with interviewing. Consideration of an interview cap would require further discussion among stake holders in the national child neurology residency training community.

There were several limitations to this study. In an attempt to maximize completion of the surveys, we chose just 10 questions for each group, so the amount of information we could obtain was limited. We did not have the updated contact information for all programs, so a small number of programs may not have been able to participate in the study. Our response rates were high for PD and PCs, but were low for CRs as only 15 CRs responded to the survey. Therefore, our results may not be indicative of their broader perspective. Given the relatively small number of respondents from each group, additional analyses were not performed.

Conclusions

If virtual residency interviewing continues, programs may need to consider increasing the number of applicants interviewed as applicants may continue to apply to more programs. Most programs combined child neurology and pediatrics interviews on one day, and the interview experience was most commonly about six hours long, including a live orientation and meeting with residents. In the future, programs may need to rethink how to structure interactions with residents to make them more useful and personal. Overall, our surveys indicated that virtual interviews may limit some aspects of programs' and applicants' assessments of each other, although there are also advantages to virtual interviews. As programs gain experience with virtual interviewing, many may want to consider how to incorporate virtual experiences in the interview process in an effort to reduce the time and expense associated with in-person interviews incurred by both applicants and programs.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.09.016.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Dixon S.M., Binkley M.M., Gospe S.M., Guerriero R.M. Child neurology applicants place increasing emphasis on quality of life factors. Pediatr Neurol. 2021;114:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Healy W.L., Bedair H. Videoconference interviews for an adult reconstruction fellowship: lessons learned. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:e114. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasadhika S., Altenbernd T., Ober R.R., Harvey E.M., Miller J.M. Residency interview video conferencing. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):426.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vadi M.G., Malkin M.R., Lenart J., Stier G.R., Gatling J.W., Applegate R.L. Comparison of web-based and face-to-face interviews for application to an anesthesiology training program: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:102–108. doi: 10.5116/ijme.56e5.491a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson K.A., Shin B., Gangadharan S.P. A comparison between in-person and virtual fellowship interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seifi A., Mirahmadizadeh A., Eslami V. Perception of medical students and residents about virtual interviews for residency applications in the United States. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewkowitz A.K., Ramsey P.S., Burrell D., Metz T.D., Rhoades J.S. Effect of virtual interviewing on applicant approach to and perspective of the maternal-fetal medicine subspecialty fellowship match. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3:100326. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhoades J.S., Ramsey P.S., Metz T.D., Lewkowitz A.K. Maternal-fetal medicine program director experience of exclusive virtual interviewing during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3:100344. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill M.V., Ross E.A., Crawford D., et al. Program and candidate experience with virtual interviews for the 2020 complex general surgical oncology interview season during the COVID pandemic. Am J Surg. 2021;222:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Program N.R.M. National Resident Matching Program; Washington, DC: 2021. National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2021 Main Residency Match®. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Program N.R.M. National Resident Matching Program; Washington, DC: 2020. National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match®. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muzumdar S., Grant-Kels J.M., Feng H. Improving the residency application process with application and interview caps. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e243–e244. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burk-Rafel J., Standiford T.C. A novel ticket system for capping residency interview numbers: reimagining interviews in the COVID-19 era. Acad Med. 2021;96:50–55. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.