Abstract

Background

Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder caused by haploinsufficiency of the SHANK3 gene and characterized by global developmental delays, deficits in speech and motor function, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Monogenic causes of ASD such as PMS are well suited to investigations with novel therapeutics, as interventions can be targeted based on established genetic etiology. While preclinical studies have demonstrated that the neuropeptide oxytocin can reverse electrophysiological, attentional, and social recognition memory deficits in Shank3-deficient rats, there have been no trials in individuals with PMS. The purpose of this study is to assess the efficacy and safety of intranasal oxytocin as a treatment for the core symptoms of ASD in a cohort of children with PMS.

Methods

Eighteen children aged 5–17 with PMS were enrolled. Participants were randomized to receive intranasal oxytocin or placebo (intranasal saline) and underwent treatment during a 12-week double-blind, parallel group phase, followed by a 12-week open-label extension phase during which all participants received oxytocin. Efficacy was assessed using the primary outcome of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Social Withdrawal (ABC-SW) subscale as well as a number of secondary outcome measures related to the core symptoms of ASD. Safety was monitored throughout the study period.

Results

There was no statistically significant improvement with oxytocin as compared to placebo on the ABC-SW (Mann–Whitney U = 50, p = 0.055), or on any secondary outcome measures, during either the double-blind or open-label phases. Oxytocin was generally well tolerated, and there were no serious adverse events.

Limitations

The small sample size, potential challenges with drug administration, and expectancy bias due to relying on parent reported outcome measures may all contribute to limitations in interpreting results.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that intranasal oxytocin is not efficacious in improving the core symptoms of ASD in children with PMS.

Trial registration NCT02710084.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13229-021-00459-1.

Keywords: Phelan-McDermid syndrome, PMS, Shank3, Autism spectrum disorder, ASD, Oxytocin

Background

Gene discovery approaches, followed by functional analysis using model systems, have clarified the neurobiology of several genetic subtypes of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and led to important opportunities for developing novel therapeutics [44, 48, 60, 77]. ASD is now understood to have multiple distinct genetic risk loci, and one example is SHANK3, where haploinsufficiency through deletion or sequence variants causes Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS), which is characterized by global developmental delay, motor skills deficits, delayed or absent speech, and ASD [71]. SHANK3 is the critical gene in this syndrome [15, 16, 29], and studies indicate that loss of one copy of SHANK3 causes a monogenic form of ASD with a frequency of at least 0.5% of ASD cases and up to 2% of ASD with moderate to profound intellectual disability [53]. SHANK3 codes for a master scaffolding protein in postsynaptic glutamatergic synapses and plays a critical role in synaptic function [14]. Using Shank3-deficient mice and rats, specific deficits in synaptic function and plasticity in glutamate signaling have been identified [17, 42, 44, 45, 47, 59, 70, 81]. Importantly, studies in Shank3-deficient rats have demonstrated that oxytocin reverses synaptic plasticity deficits in the hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex, in addition to reversing behavioral deficits in long-term social recognition memory and attention [45]. Furthermore, oxytocin has recently been shown to stimulate neurite outgrowth and increase gene expression of Shank3 protein in human neuroblastoma cells [84] and to reverse neurite abnormalities in Shank3-deficient mice [65].

Oxytocin is an FDA-approved, commercially available medication that can be compounded into an intranasal solution for passage through the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Oxytocin is the brain’s most abundant neuropeptide; it can act as a classical neurotransmitter, a neuromodulator, and a hormone with actions throughout the body [10, 36, 78]. In animal models, oxytocin has been demonstrated to increase social approach behavior, social recognition, social memory, and to reduce stress responses [18, 21, 52]. In humans, oxytocin is known as a strong modulator of social behavior and increases gaze to eye regions, social cognition, social memory, empathy, perceptions of trustworthiness, and cooperation within one’s own group [9, 11, 22–25, 28, 34, 35, 38, 39, 49–51, 58, 63, 66, 67, 68, 75, 76, 83].

Studies of intranasal oxytocin suggest equivocal effects on social behavior both generally and in ASD [5, 6, 22, 24–27, 40, 41, 62, 74, 82, 83]. The largest study in ASD to date did not demonstrate a significant improvement in social behavior with intranasal oxytocin [69]. There are many proposed reasons why oxytocin has proven unreliable in ASD, including due to issues around brain penetrance, dosing, and trial design [1, 54, 61]. However, the clinical and etiological heterogeneity of ASD pose prominent obstacles for successful clinical trials in ASD in general and likely contributes to challenges detecting consistent effects with oxytocin. While it is necessary to exercise caution in interpreting the literature to date as justification for the current trial, we sought to address this issue of heterogeneity by recruiting a sample population with a shared underlying genetic etiology. The following study was conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of oxytocin in children with PMS, all of whom had a deletion or pathogenic sequence variant of the SHANK3 gene. We hypothesized that individuals with PMS would show improvement in social withdrawal symptoms following oxytocin administration.

Methods

We used a double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel group design in 18 children with PMS, aged 5 to 17 years old, to evaluate the impact of oxytocin on impairments in socialization, language, and repetitive behaviors. The study protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai Program for the Protection of Human Subjects, and all caregivers signed informed consent. Participants were enrolled between May 2016 and November 2019 and randomized to receive either intranasal oxytocin or matching placebo (intranasal saline) for 12 weeks during the double-blind phase, followed by a 12-week open-label extension with intranasal oxytocin.

All participants had pathogenic deletions encompassing SHANK3 (n = 12) or SHANK3 sequence variants (n = 6). Among participants with deletions, two had ring chromosome 22. The mean deletion size was 3.1 Mb (range = 55 Kb–8.2 Mb; SD = 2.7 Mb). Among participants with sequence variants, three had p.Ala1227Glyfs*69, two had p.Leu1142Valfs*153, and one had p.Ile1094Thrfs*100. Seventeen of 18 participants met criteria for ASD based on clinical consensus using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) [56], the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) [55], and the Diagnostic Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; [4]).

The primary outcome measure was the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Social Withdrawal subscale (ABC-SW; [2]) and was selected to capture a core symptom domain in ASD. Secondary outcome measures included the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R, [13]), the Short Sensory Profile (SSP, [30]), the Macarthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (MCDI, [32, 33]), the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition [73], the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement Scales (CGI-I, [43]), and the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; [57]). The MSEL was chosen to assess cognitive ability as recommended in individuals with PMS who are often unable to complete standardized IQ tests [72], developmental quotients were calculated as previously described in the literature [31] to evaluate baseline ability, and age equivalents were used to assess change with treatment.

Additional exploratory measures were administered using electrophysiology and eye tracking paradigms, and if feasibility is established, results will be reported in a subsequent publication.

To be eligible to participate, all participants had a minimum raw score of 12 on the ABC-SW at enrollment, which was selected by adding approximately one standard deviation to the mean ABC-SW subscale score derived from a normative sample of 601 children aged 6–17 with intellectual disability [19] and as suggested by Aman and Singh [3]. All participants were on stable medication regimens for at least three months prior to enrollment and throughout the study period.

Drug administration

Oxytocin was delivered in 5-ml bottles with a dosage pump manufactured by Novartis in Europe and marketed as Syntocinon™ under an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) from the FDA (IND #104496). The first seven participants started the trial with a dose of 24 international units (IU) twice daily (BID), which was adjusted to 12 IU BID after two participants experienced increased irritability. Subsequently, after the first two-week check-in call, if the drug was well tolerated, the dose was increased to 24 IU BID. Each insufflation delivered 4 IU and three insufflations (12 IU) in each nostril were given twice daily for a total daily dose of 48 IU. The dose of 24 IU BID was chosen because it is the most commonly used in the literature in sample populations with ASD [5, 6, 40, 41, 62, 74]. Identical doses were used during the open-label treatment phase. Adherence to treatment was assessed by caregiver report and drug diary. Randomization and blinding was performed by the Mount Sinai Research Pharmacy. Caregivers received written instructions for how to administer the study drug, and the first dose was administered by the principal investigator with the caregiver observing.

Efficacy and safety measurements were taken at baseline, and at weeks 4, 8, and 12 of each treatment phase (double blind and open-label). An additional safety assessment was done at week 2 in both phases. Monitoring of adverse events (AEs) was done using an adapted semi-structured interview, the Safety and Monitoring Uniform Report Form (SMURF). AEs were documented with respect to severity, duration, management, relationship to study drug, and outcome. Severity was graded using a scale of mild, moderate, or severe. Primary and secondary outcomes were administered by an independent evaluator (DH), who was blind to side effects to prevent the risk of bias.

Data analysis

All statistical computing was performed in SPSS Version 27. Analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat population. All data were explored for outliers and data quality using descriptive statistics and graphs prior to breaking of the blind and any statistical hypothesis testing. For data on a categorical scale, we used contingency tables and histograms, and for data on a continuous scale, box-and-whisker plots.

We tested for differences in change from baseline to week 12 of the primary efficacy variable, ABC-SW, as well as all other variables by calculating the Mann–Whitney U test [46]. The Mann–Whitney U test is a nonparametric test robust to single gross outliers and does not require the data to follow any particular data distribution. We compared within subject changes from week 12 to 24 by calculating the Wilcoxon signed rank test [80]. In supplementary analyses, we fitted generalized linear regression models assuming data to follow an approximate normal distribution, which allowed us to include and adjust for the baseline value. All tests of statistical hypotheses were done on the two-sided 5% level of significance and were completed while remaining blind to treatment assignments. After selecting a single primary efficacy variable, we did not adjust for multiplicity of statistical tests. However, all raw p-values are provided for any post hoc adjustment.

Missing data

In the case of two participants who dropped out after week 4, difference scores were calculated for each outcome measure using the last observation carried forward. Two participants dropped out after baseline and were not included in the efficacy analysis (see Safety section).

Results

Double-Blind phase: baseline to week 12

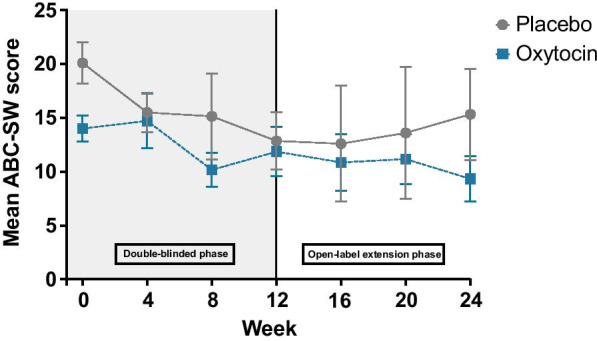

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with the exception of ABC-SW scores (Table 1). Sixteen participants were included in the efficacy analysis (See CONSORT diagram; Additional file 2: figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference between oxytocin and placebo groups on change from baseline to week 12 on the ABC-SW, our primary outcome (U = 50, median placebo change = − 7; median oxytocin change = − 3; p = 0.055) (Fig. 1). This result did not change in a regression analysis controlling for baseline differences in ABC-SW score (F = 3.41, p = 0.088) or after removing the two participants who dropped out after week 4 (U = 39.5, p = 0.053). In addition, there were no statistically significant differences between groups for any of our secondary outcomes during the double-blind phase (Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant baseline characteristics

| Sex | Placebo (N = 10) N F: 5 M: 5 |

Range | Oxytocin (N = 8) N F: 4 M: 4 |

Range | Total (N = 18) N F: 9 M: 9 |

Range | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||||

| Age (years) | 9.8 (3.6) | 6–17 | 6.8 (1.4) | 5–9 | 8.4 (3.2) | 5–17 | 0.055 | |

| Baseline ABC-SW | 20.1 (6.1) | 12–30 | 14 (3.4) | 12–20 | 17.4 (5.9) | 12–30 | 0.012* | |

| Verbal DQ | 14.9 (12.8) | 4–46 | 26.4 (21.3) | 8–61 | 20 (17.6) | 4–61 | 0.203 | |

| Nonverbal DQ | 20.1 (11.7) | 4–42 | 26.1 (13.1) | 11–50 | 22.7 (12.3) | 4–50 | 0.408 | |

| Full Scale DQ | 17.4 (11.8) | 5–44 | 26.3 (16.7) | 10–50 | 21.4 (14.5) | 5–50 | 0.173 | |

ABC-SW Aberrant Behavior Checklist Social Withdrawal subscale; DQ developmental quotient; F female; M male; N sample size; SD standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Mean scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist Social Withdrawal subscale across study visits. Bars represent standard error

Table 2.

Comparison across groups of mean change from baseline to week 12

| Measure | Variable name | Number of subjects placebo | Mean change placebo | Median change placebo | Number of subjects oxytocin | Mean change oxytocin | Median change oxytocin | Mann–Whitney U test statistic | Two-sided p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC | |||||||||

| Irritability | 9 | − 5 | − 3 | 7 | − 1.71 | 0 | 40.5 | 0.351 | |

| Social withdrawal | 9 | − 7.44 | − 7 | 7 | − 2.42 | − 3 | 50 | 0.055 | |

| Stereotypy | 9 | − 2.22 | − 1 | 7 | 0.57 | 0 | 41.5 | 0.299 | |

| Hyperactivity | 9 | − 8.11 | − 6 | 7 | − 2.71 | 0 | 42 | 0.299 | |

| Inappropriate speech | 9 | − 1.67 | 0 | 7 | − 7.14 | 0 | 35 | 0.758 | |

| RBS-R | |||||||||

| Stereotypic behaviors | 9 | − 1.67 | − 2 | 7 | 0.29 | 0 | 43 | 0.252 | |

| Self-injury | 9 | − 1.22 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 46 | 0.142 | |

| Compulsive behaviors | 9 | − 1.56 | 0 | 7 | − 0.14 | 0 | 38 | 0.536 | |

| Ritualistic behaviors | 9 | − 1.33 | − 1 | 7 | − 0.43 | 0 | 39 | 0.47 | |

| Sameness behaviors | 9 | − 2 | − 1 | 7 | − 0.29 | − 1 | 41 | 0.351 | |

| Restricted behaviors | 9 | − 1.43 | 0 | 7 | 0.14 | 0 | 23.5 | 0.902 | |

| Overall score | 9 | − 8.56 | − 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 0.142 | |

| CGI-I | |||||||||

| Severity | 9 | − 0.11 | 0 | 7 | − 0.14 | 0 | 30.5 | 0.918 | |

| Improvement* | 9 | N/A | N/A | 7 | N/A | N/A | 38 | 0.536 | |

| SSP | |||||||||

| Tactile | 9 | 2.56 | 2 | 7 | 1.57 | 0 | 29 | 0.837 | |

| Taste/smell | 9 | 1.67 | 0 | 7 | 0.71 | 0 | 28.5 | 0.758 | |

| Movement | 9 | − 0.67 | 0 | 7 | 0.29 | 0 | 41.5 | 0.299 | |

| Under-responsive/seeks sensation | 9 | 4.44 | 6 | 7 | 0.71 | 2 | 19 | 0.21 | |

| Auditory filtering | 9 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.29 | − 1 | 16 | 0.114 | |

| Low energy/weak | 9 | 1.67 | 2 | 7 | − 0.71 | 0 | 24 | 0.47 | |

| Visual/auditory sensitivity | 9 | 1.89 | 3 | 7 | − 0.86 | 0 | 13 | 0.055 | |

| Total | 9 | 14.33 | 8 | 7 | 1 | − 8 | 14.5 | 0.071 | |

| Vineland-II | |||||||||

| Communication | 7 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 2.83 | 2 | 22 | 1 | |

| Daily living skills | 7 | 3.29 | 1 | 6 | 1.17 | 0.5 | 14.5 | 0.366 | |

| Socialization | 7 | 3 | 1 | 6 | − 0.5 | − 0.5 | 12 | 0.234 | |

| Motor | 6 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3.17 | 0 | 20.5 | 0.699 | |

| Adaptive behavior composite | 7 | 3.14 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 1 | |

| Internalizing | 7 | − 1.14 | − 1 | 6 | − 0.5 | 0 | 29 | 0.295 | |

| Externalizing | 7 | − 1.14 | − 1 | 6 | − 0.17 | 0 | 25.5 | 0.534 | |

| Maladaptive | 6 | − 1.33 | 0 | 6 | − 0.5 | − 0.5 | 18 | 1 | |

| MSEL | |||||||||

| Gross motor | 7 | − 1.57 | 0 | 7 | − 0.86 | 0 | 22 | 0.805 | |

| Visual reception | 7 | 0.29 | 0 | 7 | 2.86 | 4 | 34 | 0.259 | |

| Fine motor | 7 | − 0.29 | 0 | 7 | 0.71 | 0 | 32 | 0.383 | |

| Receptive language | 7 | − 1.86 | − 1 | 7 | 1.71 | 1 | 35.5 | 0.165 | |

| Expressive language | 7 | 0.43 | 0 | 7 | 0.43 | 0 | 22 | 0.805 | |

| MCDI | |||||||||

| Phrases understood | 7 | 0.71 | 0 | 7 | 1.43 | 0 | 29.5 | 0.535 | |

| Words understood | 7 | − 8.14 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 29 | 0.62 | |

| Words produced | 7 | − 8.43 | 0 | 7 | 2.57 | 0 | 23 | 0.902 | |

| Early gestures | 7 | 1.86 | 1 | 7 | − 0.27 | 0 | 9 | 0.053 | |

| Later gestures | 7 | 2.71 | 1 | 7 | 0.86 | 1 | 26 | 0.902 | |

| Total gestures | 7 | 4.57 | 1 | 7 | 0.57 | 1 | 18 | 0.456 |

*CGI-I scores reflect results at Week 12 only; Vineland-II domain and composite values are standard scores; MSEL values are age equivalents

ABC Aberrant Behavior Checklist; AE age equivalent; CGI Clinical Global Impression-Improvement Scale; MCDI Macarthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory; MSEL Mullen Scales of Early Learning; RBS Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised; SSP Short Sensory Profile

Five participants were receiving concomitant psychotropic medications during the study period; three were randomized to the placebo group and two were randomized to oxytocin. All doses remained stable throughout the trial. Among participants in the placebo group, psychotropic medications included aripiprazole, tizanidine, mirtazapine, and doxepin (n = 1), clonidine and lisdexamfetamine (n = 1), divalproex sodium (n = 1), and melatonin (n = 2). Among the participants in the oxytocin group, medications included gabapentin, oxcarbazepine, and melatonin (n = 1) and levetiracetam (n = 1).

Open-label phase: week 12 to week 24

We further examined within-subject change on all outcome measures during the open-label phase of the trial for each group individually and across all participants. There were no statistically significant improvements on any outcome measure between week 12 and week 24 in either group or across all participants.

Safety

Eighteen participants were included in the safety analysis. Oxytocin was generally well tolerated, and there was no statistically significant difference between groups in the frequency of AEs (U = 37, p = 0.83). Three participants withdrew from the study during the double-blind phase due to tolerability concerns: one participant developed croup and a sinus infection (placebo) and the caregivers stopped the study drug on their own; two participants developed worsening irritability (one placebo; one oxytocin) and withdrew in consultation with the principal investigator. A fourth participant dropped out after receiving a single dose of study drug (placebo) due to concerns unrelated to tolerability (Additional file 2: figure 2). There were no serious adverse events (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reported adverse events from randomization through week-12

| Adverse events | Placebo | Oxytocin |

|---|---|---|

| Sedation | 2 (20%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Decreased appetite | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Periorbital/facial swelling | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (10%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (20%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Sleep disturbance | 2 (20%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Increased appetite | 1 (10%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Irritability/agitation | 3 (30%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Cough | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Runny nose/congestion | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fever | 5 (50%) | 2 (25%) |

| Aggression/self-injury | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Infection | 3 (30%) | 2 (25%) |

| Elated mood/silliness | 1 (10%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Leg weakness | 1 (10%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Restlessness/hyperactivity | 1 (10%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Bloody nose | 0 (0%) | 2 (25%) |

| Stereotypies | 2 (20%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Apathy | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Foot pain | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hirsutism | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Tooth pain | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Eczema | 1 (10%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Allergies/asthma | 2 (20%) | 2 (25%) |

| Enuresis | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Accidental injury | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Seizure | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Rubbing ears | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Disinhibited | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Oppositional behavior | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Low frustration tolerance | 1 (10%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Tantrums | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Total | 41 | 35 |

Discussion

The results of this small study do not support the use of intranasal oxytocin in PMS. Despite promising preclinical data and a plausible biological rationale, attempts to reduce genetic heterogeneity by selecting only participants with PMS were not adequate to identify a population in which oxytocin treatment would show more uniform impact on social behavior. The lack of a treatment effect highlights the challenges in translating from animal and other preclinical models to humans. While preclinical models may show strong construct validity, outcome measures, dosing, and bioavailability are difficult to replicate in humans. Outcome measures in preclinical studies have the advantage of enhanced objectivity and quantifying change, while clinical studies in ASD rely mainly on parent-report measures which capture ratings of behavior using relatively broad questions and are vulnerable to subjective bias. Further, while most of the outcome measures used in this study, including the ABC-SW, have been carefully validated in ASD and intellectual disability, none have undergone rigorous psychometric testing in PMS as of yet.

In terms of dosing, most studies with intranasal oxytocin in ASD continue to use 24 IU, but there have been no dose response studies to establish the appropriate dosing for different ages or populations. Differential effects may also occur based on acute versus chronic dosing; both methods appear to enhance functional connectivity in adult wild-type mice, but repeated administration was associated with reduced social interaction and communication in at least one study [61]. Likewise, differential effects were evident in a recent clinical trial in adults with ASD using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy such that chronic dosing was associated with significant reductions in medial prefrontal cortical N-acetylaspartate and glutamate levels, whereas acute dosing was not [12]. Equally important, intranasal delivery is fraught with challenges, especially for severely impaired populations who do not reliably follow instructions. Several studies have established brain penetrance with intranasal oxytocin in ASD based on functional imaging studies, [7, 8, 26, 37, 79], but participants were mostly adult males without comorbid intellectual disability. As such, differential effects across studies and sample populations may well relate to poorly controlled delivery and variability in absorption from the olfactory epithelium [1, 64]. However, this variability does not appear to contribute to tolerability issues, and AEs did not differ between groups in the present study, a finding consistent with at least one large meta-analysis of reported AEs from clinical trials with intranasal oxytocin in ASD [20]. Also, worth noting, in the study with Shank3-deficient rats that served in part as the basis for this clinical trial, oxytocin was administered though intracerebroventricular injection and not intranasally [45]. Future studies might also control for baseline levels of oxytocin as variability in underlying oxytocin regulation may contribute to differential responses; individuals with lower pre-treatment oxytocin levels may show the greatest improvement in social responsiveness [62].

Limitations

Drawing definitive conclusions about the efficacy of oxytocin in PMS based on the results of this study is limited by our small sample size, a challenge inherent to studying rare disorders. In fact, we ended our trial after three years due to challenges with recruitment and perhaps stopped before enrolling an adequate sample size to detect small effects. Our dosing paradigm also did not account for the relatively broad age range, pubertal status, or baseline levels of oxytocin. In addition, despite adequate training on drug administration, six insufflations twice daily may have been challenging for some participants. Compliance was monitored using parent report and drug diaries, but given that our study drug was administered at home, it is possible that doses were missed or not properly administered. Further, the majority of our measures, including the primary outcome, rely on subjective parent reporting and have not been well validated for use in clinical trials in PMS. Finally, preclinical models benefit from genetic homogeneity and while all the individuals in our sample had SHANK3 haploinsufficiency, it was comprised of those with 22q13 deletions of varying sizes (n = 12), in addition to SHANK3 sequence variants (n = 6). However, the present study was too small to examine subset analyses but this may be a worthy endeavor for future studies.

Conclusions

While the results of this study must be interpreted with caution in light of the limitations, intranasal oxytocin does not appear efficacious in improving the core symptoms of ASD in children with PMS. Despite these findings and inconsistent results across studies, enthusiasm persists for oxytocin as a treatment for ASD symptoms. Future studies must address this complex multitude of confounding factors to advance oxytocin as a treatment in ASD and related neurodevelopmental disorders. In addition to genetics, other biomarkers, such as using electrophysiology, to stratify sample populations and attempt to predict treatment response have the potential to improve clinical trial designs. The development of new outcome measures, refined and validated for specific genetic forms of ASD, may also help. Importantly, outcome measures that incorporate objective assessments will be more likely to reduce bias. Finally, exploring novel mechanisms for intranasal delivery to enhance absorption in addition to clarifying optimal dosing regimens will be critical for future trial success. Nevertheless, a genetics-first approach and other methods to limit heterogeneity in clinical trial populations remain a promising path forward for studies in ASD and related neurodevelopmental disorders.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:Supplementary Table 1: Mean values for all measures across groups at baseline and week 12.

Additional file 2: figure 2. CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through Week 12

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families who participated and the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation for their support in recruitment.

Abbreviations

- ABC

Aberrant Behavior Checklist

- ADI-R

Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised

- ADOS-2

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition

- DSM-5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

- AE

Age equivalent

- AEs

Adverse events

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- DQ

Developmental quotient

- CGI-I

Clinical Global Impression-Improvement Scale

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IU

International units

- MCDI

Macarthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory

- MSEL

Mullen Scales of Early Learning

- PMS

Phelan-McDermid syndrome

- RBS-R

Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised

- SMURF

Safety monitoring report form

- SSP

Short Sensory Profile

- Vineland-II

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales

Authors' contributions

JF and SS contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing; AK, JFF, YF, DH, PT, PS, and JZ contributed to study design, data collection, and manuscript writing; CL and LT collected and entered data for analysis; HHN and JDB contributed to manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Beatrice and Samuel A. Seaver Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai Program for the Protection of Human Subjects and all caregivers signed informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AK receives research support from AMO Pharma and consults to Acadia, Alkermes, and Ovid Therapeutics. JDB has a shared patent with Mount Sinai for IGF-1 in Phelan-McDermid syndrome. No other authors have competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alvares GA, Quintana DS, Whitehouse AJ. Beyond the hype and hope: Critical considerations for intranasal oxytocin research in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017;10(1):25–41. doi: 10.1002/aur.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. The aberrant behavior checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Defic. 1985;89(5):485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aman MG, Singh NN. Supplement to Aberrant Behavior Checklist manual. East Aurora: Slosson Educational Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Publishing: Lansing. USA: MI; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anagnostou E, Soorya L, Chaplin W, et al. Intranasal oxytocin versus placebo in the treatment of adults with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Mol Autism. 2012;3(1):16. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andari E, Duhamel JR, Zalla T, Herbrecht E, Leboyer M, Sirigu A. Promoting social behavior with oxytocin in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4389–4394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910249107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki Y, Yahata N, Watanabe T, Takano Y, Kawakubo Y, Kuwabara H, Iwashiro N, Natsubori T, Inoue H, Suga M, Takao H, Sasaki H, Gonoi W, Kunimatsu A, Kasai K, Yamasue H. Oxytocin improves behavioural and neural deficits in inferring others' social emotions in autism. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 11):3073–3086. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoki Y, Watanabe T, Abe O, Kuwabara H, Yahata N, Takano Y, Iwashiro N, Natsubori T, Takao H, Kawakubo Y, Kasai K, Yamasue H. Oxytocin's neurochemical effects in the medial prefrontal cortex underlie recovery of task-specific brain activity in autism: a randomized controlled trial. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(4):447–453. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartz JA, Nitschke JP, Krol SA, Tellier PP. Oxytocin selectively improves empathic accuracy: a replication in men and novel insights in women. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2019;4(12):1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Baskerville TA, Douglas AJ. Dopamine and oxytocin interactions underlying behaviors: potential contributions to behavioral disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(3):e92–123. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron. 2008;58(4):639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benner S, Aoki Y, Watanabe T, Endo N, Abe O, Kuroda M, Kuwabara H, Kawakubo Y, Takao H, Kunimatsu A, Kasai K, Bito H, Kakeyama M, Yamasue H. Neurochemical evidence for differential effects of acute and repeated oxytocin administration. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(2):710–720. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: comparisons to mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):237–243. doi: 10.1023/A:1005596502855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boeckers TM. The postsynaptic density. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;362:409–422. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Mani E, Aceti G, Anderlid BM, Barconcini A, Pramparo T, Zuffardi O. Identification of a recurrent breakpoint within the SHANK3 gene in the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;10:822–828. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.038604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Beri S, De Agostini C, et al. Molecular mechanisms generating and stabilizing terminal 22q13 deletions in 44 subjects with Phelan/McDermid syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Bozdagi, O, Sakurai, T, Papapetrou, D, Wang, X, Dickstein, DL, Takahashi, N, Kajiwara, Y, Yang, M, Katz, AM, Scattoni, ML, Harris, MJ, Saxena, R, Silverman, JL, Crawley, JN, Zhou, Q, Hof, PR, Buxbaum JD. Halpoinsufficiency of the autism-associated SHANK3 gene leads to deficits in synaptic function, social interaction, and social communication. Mol Autism. 2010;1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Braida D, et al. Neurohypophyseal hormones manipulation modulate social and anxiety-related behavior zebrafish. Psychopharmacology. 2012;220:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown EC, Aman MG, Havercamp SM. Factor analysis and norms for parent ratings on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Community for young people in special education. Res Dev Disabil. 2002;23(1):45–60. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(01)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai Q, Feng L, Yap KZ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of reported adverse events of long-term intranasal oxytocin treatment for autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(3):140–151. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang SW, Platt ML. Oxytocin and social cognition in rhesus macaques: implications for understanding and treating human psychopathology. Brain Res. 2014;1580:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Dreu CK, Greer LL, Handgraaf MJ, Shalvi S, Van Kleef GA, Baas M, Ten Velden FS, Van Dijk E, Feith SW. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science. 2010;328(5984):1408–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.1189047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Simplicio M, Massey-Chase R, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. Oxytocin enhances processing of positive versus negative emotional information in healthy male volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(3):241–248. doi: 10.1177/0269881108095705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ditzen B, Schaer M, Gabriel B, Bodenmann G, Ehlert U, Heinrichs M. Intranasal oxytocin increases positive communication and reduces cortisol levels during couple conflict. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):728–731. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domes G, Lischke A, Berger C, Grossmann A, Hauenstein K, Heinrichs M, Herpertz SC. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on emotional face processing in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(1):83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domes G, Heinrichs M, Kumbier E, Grossmann A, Hauenstein K, Herpertz SC. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on the neural basis of face processing in autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(3):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domes G, Kumbier E, Heinrichs M, Herpertz SC. Oxytocin promotes facial emotion recognition and amygdala reactivity in adults with asperger syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(3):698–706. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dumais KM, Veenema AH. Vasopressin and oxytocin receptor systems in the brain: Sex differences and sex-specific regulation of social behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2016;40:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, Bockmann J, Chaste P, Fauchereau F, Nygren G, Rastam M, Gillberg IC, Anckarsäter H, Sponheim E, Goubran-Botros H, Delorme R, Chabane N, Mouren-Simeoni MC, de Mas P, Bieth E, Rogé B, Héron D, Burglen L, Gillberg C, Leboyer M, Bourgeron T. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):25–27. doi: 10.1038/ng1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn, W. Sensory Profile. The Psychological Corporation. 1999.

- 31.Farmer C, Golden C, Thurm A. Concurrent validity of the differential ability scales, second edition with the Mullen Scales of Early Learning in young children with and without neurodevelopmental disorders. Child Neuropsychol. 2016;22(5):556–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Thal DJ, Bates E, Hartung JP, Pethick S, Reilly JS. MacArthur communicative development inventories: user’s guide and technical manual. Baltimore: Paul H. Brokes Publishing Co.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fenson, L, Marchman, VA, Thal, DJ, Dale, PS, Reznick, JS, Bates, E. MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories: user’s guide and technical manual (2nd ed.) Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co. 2007.

- 34.Fischer-Shofty M, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Levkovitz Y. Characterization of the effects of oxytocin on fear recognition in patients with schizophrenia and in healthy controls. Front Neurosci. 2018;7:127. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabor CS, Phan A, Clipperton-Allen AE, Kavaliers M, Choleris E. Interplay of oxytocin, vasopressin, and sex hormones in the regulation of social recognition. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126(1):97–109. doi: 10.1037/a0026464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gimple G, Fahrenholz F. The Oxytocin Receptor System: Structure, Function, and Regulation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):629–683. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon I, Vander Wyk BC, Bennett RH, Cordeaux C, Lucas MV, Eilbott JA, Zagoory-Sharon O, Leckman JF, Feldman R, Pelphrey KA. Oxytocin enhances brain function in children with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(52):20953–20958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312857110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Mathews F. Oxytocin enhances the encoding of positive social memories in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(3):256–258. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Dadds MR. Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guastella AJ, Gray KM, Rinehart NJ, Alvares GA, Tonge BJ, Hickie IB, Keating CM, Cacciotti-Saija C, Einfeld SL. The effects of a course of intranasal oxytocin on social behaviors in youth diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(4):444–452. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guastella AJ, Einfeld SL, Gray KM, et al. Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):692–694. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo B, Chen J, Chen Q, Ren K, Feng D, Mao H, Yao H, Yang J, Liu H, Liu Y, Jia F, Qi C, Lynn-Jones T, Hu H, Fu Z, Feng G, Wang W, Wu S. Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction underlies social deficits in Shank3 mutant mice. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(8):1223–1234. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology—Revised (DHEW Publ No ADM 76-338). Rockville, MD, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extra-mural Research Programs. 1976;218–222.

- 44.Harony-Nicolas H, De Rubeis S, Kolevzon A, Buxbaum JD. Phelan McDermid syndrome: from genetic discoveries to animal models and treatment. J Child Neurol. 2015;30(14):1861–1870. doi: 10.1177/0883073815600872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harony-Nicolas H, Kay M, du Hoffmann J, Klein ME, Bozdagi-Gunal O, Riad M, Daskalakis NP, Sonar S, Castillo PE, Hof PR, Shapiro ML, Baxter MG, Wagner S, Buxbaum JD. Oxytocin improves behavioral and electrophysiological deficits in a novel Shank3-deficient rat. Elife. 2017;6:e18904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Hettmansperger T, McKean J. Robust Nonparametric Statistical Methods, Second Edition. 2nd ed. 2010.

- 47.Jacot-Descombes S, Keshav NU, Dickstein DL, Wicinski B, Janssen WGM, Hiester LL, Sarfo EK, Warda T, Fam MM, Harony-Nicolas H, Buxbaum JD, Hof PR, Varghese M. Altered synaptic ultrastructure in the prefrontal cortex of Shank3-deficient rats. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13229-020-00393-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Javed S, Selliah T, Lee YJ, Huang WH. Dosage-sensitive genes in autism spectrum disorders: from neurobiology to therapy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;118:538–567. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kéri S, Benedek G. Oxytocin enhances the perception of biological motion in humans. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2009;9(3):237–241. doi: 10.3758/CABN.9.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kimura T, Tanizawa O, Mori K, Brownstein MJ, Okayama H. Structure and expression of a human oxytocin receptor. Nature. 1992;356(6369):526–529. doi: 10.1038/356526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 2005;435(7042):673–676. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kubota Y, et al. Structure and expression of the mouse oxytocin receptor gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;124:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(96)03923-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leblond CS, Nava C, Polge A, Gauthier J, Huguet G, Lumbroso S, Giuliano F, Stordeur C, Depienne C, Mouzat K, Pinto D, Howe J, Lemière N, Durand CM, Guibert J, Ey E, Toro R, Peyre H, Mathieu A, Amsellem F, Rastam M, Gillberg IC, Rappold GA, Holt R, Monaco AP, Maestrini E, Galan P, Heron D, Jacquette A, Afenjar A, Rastetter A, Brice A, Devillard F, Assouline B, Laffargue F, Lespinasse J, Chiesa J, Rivier F, Bonneau D, Regnault B, Zelenika D, Delepine M, Lathrop M, Sanlaville D, Schluth-Bolard C, Edery P, Perrin L, Tabet AC, Schmeisser MJ, Boeckers TM, Coleman M, Sato D, Szatmari P, Scherer SW, Rouleau GA, Betancur C, Leboyer M, Gillberg C, Delorme R, Bourgeron T. Meta-analysis of SHANK Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(9):e1004580. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Leng G, Ludwig M. Intranasal oxytocin: myths and delusions. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(3):243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop D. The autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition (ADOS-2) manual (Part 1): Modules 1–4. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2012.

- 57.Mullen E. Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitre M, et al. A distributed network for social cognition enriched for oxytocin receptors. J Neurosci. 2016;36:2517–2535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2409-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monteiro P, Feng G. SHANK proteins: roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(3):147–157. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mossink B, Negwer M, Schubert D, Nadif Kasri N. The emerging role of chromatin remodelers in neurodevelopmental disorders: a developmental perspective. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Pagani M, De Felice A, Montani C, Galbusera A, Papaleo F, Gozzi A. Acute and repeated intranasal oxytocin differentially modulate brain-wide functional connectivity. Neuroscience. 2020;445:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parker KJ, Oztan O, Libove RA, Sumiyoshi RD, Jackson LP, Karhson DS, Summers JE, Hinman KE, Motonaga KS, Phillips JM, Carson DS, Garner JP, Hardan AY. Intranasal oxytocin treatment for social deficits and biomarkers of response in children with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(30):8119–8124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705521114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petrovic P, Kalisch R, Singer T, Dolan RJ. Oxytocin attenuates affective evaluations of conditioned faces and amygdala activity. J Neurosci. 2008;28(26):6607–6615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4572-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quintana DS, Alvares GA, Hickie IB, Guastella AJ. Do delivery routes of intranasally administered oxytocin account for observed effects on social cognition and behavior? A two-level model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;49:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reichova A, Bacova Z, Bukatova S, Kokavcova M, Meliskova V, Frimmel K, Ostatnikova D, Bakos J. Abnormal neuronal morphology and altered synaptic proteins are restored by oxytocin in autism-related SHANK3 deficient model. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2020;518:110924. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Richard P, Moos F, Freund-Mercier MJ. Central effects of oxytocin. Physiol Rev. 1991;71(2):331–370. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rimmele U, Hediger K, Heinrichs M, Klaver P. Oxytocin makes a face in memory familiar. J Neurosci. 2009;29(1):38–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4260-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Savaskan E, Ehrhardt R, Schulz A, Walter M, Schächinger H. Post-learning intranasal oxytocin modulates human memory for facial identity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(3):368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sikich L, on behalf of ACE SOARS Network, (2019). SOARS-B: A large, phase II RCT of daily oxytocin in ASD for enhancing reciprocal social behaviors. 66th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October 19th, 2019, Chicago, IL.

- 70.Song TJ, Lan XY, Wei MP, Zhai FJ, Boeckers TM, Wang JN, Yuan S, Jin MY, Xie YF, Dang WW, Zhang C, Schön M, Song PW, Qiu MH, Song YY, Han SP, Han JS, Zhang R. Altered Behaviors and Impaired Synaptic Function in a Novel Rat Model With a Complete Shank3 Deletion. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:111. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Soorya L, Kolevzon A, Zweifach J, Lim T, Dobry Y, Schwartz L, Frank Y, Wang AT, Cai G, Parkhomenko E, Halpern D, Grodberg D, Angarita B, Willner JP, Yang A, Canitano R, Chaplin W, Betancur C, Buxbaum JD. Prospective investigation of autism and genotype-phenotype correlations in 22q13 deletion syndrome and SHANK3 deficiency. Mol Autism. 2013;4(1):18. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soorya L, Leon J, Trelles MP, Thurm A. Framework for assessing individuals with rare genetic disorders associated with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD): the example of Phelan McDermid Syndrome. Clin Neuropsychol. 2018;32(7):1226–1255. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2017.1413211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sparrow, SS, Balla, DA, and Cicchetti, DV, Vineland adaptive behaviour scales: a revision of the vineland social maturity scale by Edgar A. Doll. Circle-Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. 1984.

- 74.Tachibana M, Kagitani-shimono K, Mohri I, et al. Long-term administration of intranasal oxytocin is a safe and promising therapy for early adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013;23(2):123–127. doi: 10.1089/cap.2012.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Theodoridou A, Rowe AC, Penton-Voak IS, Rogers PJ. Oxytocin and social perception: oxytocin increases perceived facial trustworthiness and attractiveness. Horm Behav. 2009;56(1):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Unkelbach C, Guastella AJ, Forgas JP. Oxytocin selectively facilitates recognition of positive sex and relationship words. Psychol Sci. 2008;19(11):1092–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Varghese M, Keshav N, Jacot-Descombes S, Warda T, Wicinski B, Dickstein DL, Harony-Nicolas H, De Rubeis S, Drapeau E, Buxbaum JD, Hof PR. Autism spectrum disorder: neuropathology and animal models. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134(4):537–566. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1736-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Veening JG, Olivier B. Intranasal administration of oxytocin: behavioral and clinical effects, a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(8):1445–65. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Watanabe T, Abe O, Kuwabara H, Yahata N, Takano Y, Iwashiro N, Natsubori T, Aoki Y, Takao H, Kawakubo Y, Kamio Y, Kato N, Miyashita Y, Kasai K, Yamasue H. Mitigation of sociocommunicational deficits of autism through oxytocin-induced recovery of medial prefrontal activity: a randomized trial. JAMA Psychiat. 2014;71(2):166–175. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics Bulletin. 1945;6:80–83. doi: 10.2307/3001968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang M, Bozdagi O, Scattoni ML, et al. Reduced excitatory neurotransmission and mild autism-relevant phenotypes in adolescent Shank3 null mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32(19):6525–6541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6107-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yatawara CJ, Einfeld SL, Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Guastella AJ. The effect of oxytocin nasal spray on social interaction deficits observed in young children with autism: a randomized clinical crossover trial. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(9):1225–1231. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zak PJ, Kurzban R, Matzner WT. Oxytocin is associated with human trustworthiness. Horm Behav. 2005;48(5):522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zatkova M, Reichova A, Bacova Z, Strbak V, Kiss A, Bakos J. Neurite outgrowth stimulated by oxytocin is modulated by inhibition of the calcium voltage-gated channels. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2018;38(1):371–378. doi: 10.1007/s10571-017-0503-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1:Supplementary Table 1: Mean values for all measures across groups at baseline and week 12.

Additional file 2: figure 2. CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through Week 12

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.