Abstract

Purpose:

To report the results of the survey for the role of anti-VEGF in the management of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) among the members of Indian ROP (iROP) society.

Methods:

A questionnaire was designed in English using Google forms and its link was circulated to the members of the iROP society on their mobile numbers. The survey included questions pertaining to demographics, anti-VEGF agents, injection technique, post-injection follow-up, and documentation pertaining to their ROP practice. Anonymous responses were obtained and analyzed for individual questions.

Results:

226 members of the society were contacted and 157 responded (69.4%) to the survey. 137 (87.2%) respondents used anti-VEGF in the management of ROP. Aggressive posterior ROP (APROP) was the most common indication (78, 52.7%). The procedure was carried out in the main operation room (102, 70.3%) simultaneously for both the eyes (97; 68%) under topical anesthesia (134; 86.4%) by most of the respondents. One-hundred thirteen (77.9%) respondents used half of the adult dose, irrespective of the agent used; however, more than half of them preferred bevacizumab (85, 54%). 53 (36.3%) respondents followed up infants as per disease severity rather than a fixed schedule while only 33 (23%) performed photo documentation. 151 (96.2%) respondents felt the need for guidelines regarding the usage of anti-VEGF in ROP.

Conclusion:

There is an increase in the trend towards the use of anti-VEGF in the management of severe ROP, particularly APROP. However, there are considerable variations among the ROP practitioners regarding the agent, dosage, follow-up schedule, and documentation, suggesting the need for uniform guidelines.

Keywords: Anti-VEGF, India, retinopathy of prematurity, survey

Annually an estimated 14.8 million preterm infants are born worldwide. In a developing country like India, this situation becomes complex as 23.4% of the world's premature births are from India,[1] and severe forms of ROP are commonly reported even in larger babies.[2,3,4] India accounts for 10% of the world's ROP related blindness,[1] possibly due to improved survival of the preterm infants coupled with a relative paucity of trained ophthalmologists for timely screening and treatment for ROP.[5] To address these unique issues, the Indian Retinopathy of Prematurity (iROP) society, comprising of ophthalmologists from various sub-specialties, who are actively engaged in ROP screening and treatment in different parts of India, was established in 2016.[5]

Laser photocoagulation of the avascular retina remains the standard of care for the management of severe ROP[6] and has a documented anatomical success rate over 90% in Type 1 ROP.[6] However, the ablation of the peripheral retina may influence the prevalence of refractive error or possible visual field loss in the long term.[6,7] Anatomical outcomes following laser in aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity (APROP) are not as good as classical staged (Type 1) ROP.[6,8]

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a key role in the angiogenesis of immature retina as well as in the pathogenesis of ROP.[9] Following encouraging results of BEAT-ROP and RAINBOW trials, anti-VEGF has been seen as a viable treatment option for severe ROP.[10,11] Besides relative ease of administration, anti-VEGF not only halts the growth of pathological retinal vessels but may promote the growth of normal retinal vessels into the immature retina. Hypothetically, this may help to preserve more functional retina. However, the use of anti-VEGF has multiple inherent risks such as development of cataract, endophthalmitis, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal detachment.[12] Delayed recurrence of retinopathy has been documented with anti-VEGF in ROP, making a long-term follow-up essential.[13,14,15] Suppression of systemic VEGF following intravitreal anti-VEGF injection may have a deleterious effect on the development of other organs including the nervous system of the preterm infant.[14] Furthermore, there are no established national or international guidelines and protocols regarding use, dosage, or follow-up regimen after the use of anti-VEGF in ROP.

A survey of the initial 113 members of iROP society, conducted in 2017, showed that laser was still the preferred modality of treatment in 98% of the members and 86% were comfortable with it. Anti-VEGF agents had lower popularity and confidence among the members, with 41% having never used it for ROP treatment.[5] This prompted the current survey, aiming to study and interpret the practice patterns of using anti-VEGF as a therapy for ROP by specialists in India.

Methods

Survey development

Survey questionnaire was developed by reviewing previously conducted surveys among vitreoretinal surgeons[16] and pediatric ophthalmologists[17] and adapting them to the Indian scenario.

Survey population and design

A total of 226 iROP society members (at the time of the study) were contacted for the survey. The survey questionnaire was designed on Google forms® (https://www.google.com/forms/about/) in English and sent as a link to the registered mobile number of the members. Most of the questions had multiple options, with the single best answer to select from [Supplemental Table 1].

Supplemental Table 1.

The survey questionnaire

| Anti-vegf in retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) survey (Indian rop society) |

|---|

| Age (Years) |

| Gender: |

| Male |

| Female |

| Prefer Not To Say |

| Other ____ |

| Where do you practice: |

| Own Clinic |

| Government Institute |

| Private Institute |

| Charitable Institute |

| Other ____ |

| Approximate years of experience in Ophthalmology |

| Which sub speciality do you practice: |

| Vitreo Retina |

| Medical Retina |

| Pediatric Ophthalmology |

| Comprehensive/General Ophthalmology |

| Other ____ |

| Approximate years of experience in sub speciality |

| Professional memberships: |

| Vitreoretinal Society Of India (VRSI) |

| Indian ROP (iROP) Society |

| Strabismus And Pediatric Ophthalmological Society Of India (SPOSI) |

| All India Ophthalmological Society Of India (AIOS) |

| Approximate years of experience in ROP screening and treatment |

| Approximate number of infants screened per month (fresh and follow up) |

| Approximate number of infants treated per month |

| Do you use anti-VEGF injection in treating ROP |

| Yes |

| No |

| Approximate no. of infants treated with anti-VEGF per month: |

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| >10 |

| Other ____ |

| In which of the following situation you are most likely to use anti-VEGF: |

| Type 1 ETROP (staged ROP with plus disease) |

| APROP/Hybrid ROP |

| When laser cannot be done (non-dilating pupil, dense tunica vasculosa lentis, vitreous haze) |

| Persistent or recurrent plus disease |

| Not applicable |

| Other____ |

| Which anti-VEGF do you most often use in ROP? (Considering Safety, Efficacy, Medico Legal Issue, Cost): |

| Bevacizumab |

| Ranibizumab |

| Aflibercept |

| Bio similar (Razumab) |

| Other____ |

| Did injecting anti-VEGF for ROP in your practice under go any change after the DGCI ban on Avastin (ban was lifted for adults) |

| Yes, I have stopped using anti-VEGF altogether for ROP |

| Yes, I have stopped using Avastin and started using Ranibizumab for ROP |

| Yes, I am still using avastin but taking a written informed consent where details about off label use, lack of safety profile in preterm and possible effect on neuro development are mentioned |

| No, I am still using avastin with general consent for intravitreal injection |

| Not applicable |

| Other___ |

| What dose of anti-VEGF do you use in ROP? |

| Similar to an adult dose |

| Half of an adult dose |

| One-fourth of an adult dose |

| Less than one-fourth of an adult dose |

| Not applicable |

| Other____ |

| What type of anaesthesia do you use during intravitreal injection in infants? |

| Topical |

| General |

| Sedation |

| Not applicable |

| Other____ |

| Where do you perform the injection procedure? |

| Out patient |

| Minor OR |

| Main OR |

| NICU |

| Any of the above depending up on the systemic status of the neonate |

| Not applicable |

| At what distance from limbus do you inject anti-VEGF in preterm infants? |

| 1MM |

| 1.5MM |

| 2MM |

| Not applicable |

| Which quadrant do you prefer for injecting anti-VEGF in preterm infants? |

| Supero nasal |

| Supero temporal |

| Infero nasal |

| Infero temporal |

| Any of the above depending upon infants bells reflex |

| Not applicable |

| Other____ |

| What is your treatment protocol? |

| One eye at a time |

| Both eyes together |

| Not applicable |

| Other____ |

| When do you inject in other eye? (if you are injecting in one at a time) |

| How do you obtain and prepare your anti-VEGF injection for ROP? |

| Pre filled syringes and stored in refrigerator |

| Lab made aliquots and stored in refrigerator |

| Direct from vial (single use) |

| Direct from vial (multiple use) |

| Not applicable |

| Other____ |

| What is your follow up protocol/schedule after injection of anti-VEGF? |

| Twice a week |

| Weekly |

| Fortnightly |

| Guided by the disease severity prior to injection |

| Not applicable |

| Other____ |

| What type of consent do you take before using anti-VEGF in ROP? |

| I am taking a specially drafted/written consent before using anti-VEGF in ROP |

| AIOS and VRSI consent for Avastin |

| A general consent for anti-VEGF injection/surgery |

| I am not taking consent before using anti-VEGF in ROP |

| Not applicable |

| Does your consent form have points that the drug is ‘off label, not validated for safety and can cause potential unknown and known side effects including neuro developmental delay and abnormalities? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Sometimes or partly |

| Not applicable |

| Do you photo document your cases before and after giving injection anti-VEGF? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Sometimes or partly |

| Not applicable |

| Do you perform fundus angiography any timeprior, or after injection anti-VEGF |

| Yes |

| No |

| Sometimes or partly |

| Not applicable |

| Do you perform any additional systemic monitoring for eyes that receive anti-VEGF medication (over and above laser treated eyes)? |

| Yes |

| No |

| On discretion of neonatologist |

| Not applicable |

| Are you aware that VRSI has provided guidelines for use of anti-VEGF in adults (after the ban was lifted) but does not mention the use of the drug in infants or ROP? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Do you feel the need for a recommendation on the use of anti-VEGF for treatment of ROP in INDIA? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Are the results of this survey likely to alter your pattern of anti-VEGF use in ROP? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Cannot say at present |

Survey administration

The study met the approval of the Institutional Review Board and did not involve any patient information or identifiers. The results were submitted anonymously through the provided web link that was active from 21st February 2019 to 31st March 2019. The participants submitted their responses through their smartphones.

Data management and analysis

The responses were collated on a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel. The result of each question was analyzed based on the number of responses obtained, individually. Responses excluding the “not applicable” were analyzed. Categorical variables were summarized by counts and percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed by mean and standard deviations. Subgroup analysis of the responses was also done, based on age (age ≤ 40 and age > 40) and practice setting of the respondent, and these were compared with multiple variables. Pearson Chi-square test was used to know the association between variables. P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics and general practice

Among the 226 members with whom the survey link was shared, 157 responded (69.4%). The mean age of the respondents was 38.3 ± 11.6 (range: 27–62) years and there was a male preponderance (109, 69.4%). The majority of the respondents were vitreoretinal surgeons (129, 82.1%) and were practicing in private institutes (66, 42%) with an average experience of 8.9 ± 8.9 (range: 0.5-25) years in ROP screening and treatment. Each respondent screened an average 77.1 ± 203.5 (median: 30, range: 2–2000) and treated 4.4 ± 5.3 infants (median: 3, range: 0–30) per month. One-hundred fifty respondents (95.5%) were registered members of the All India Ophthalmological Society (AIOS), 111 (70.7%) were members of Vitreoretinal Society of India (VRSI), and 11 (7%) were members of Strabismus and Pediatric Ophthalmological Society of India (SPOSI).

Anti-VEGF: Indications, agents, technique, and follow-up

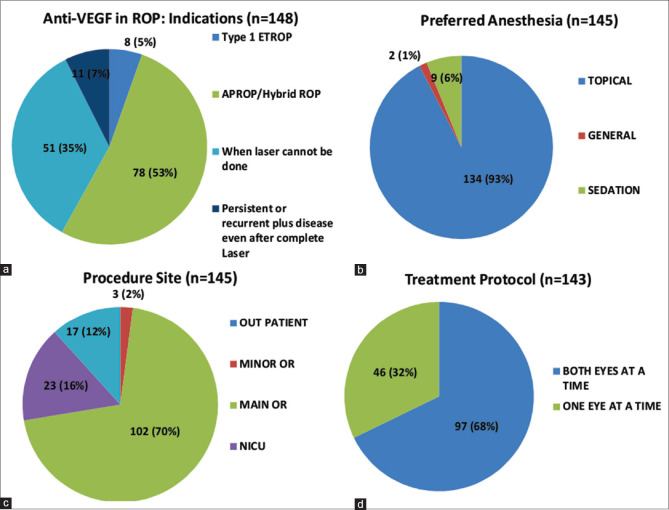

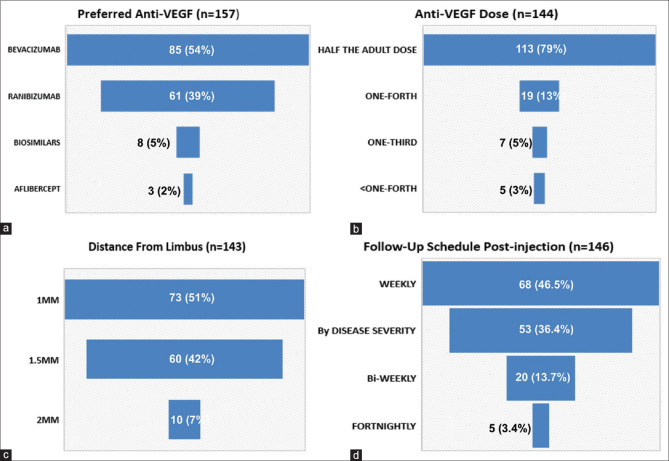

The most common indication for using anti-VEGF was APROP/Hybrid ROP (78, 52.7%) (Hybrid ROP: presence of ridge tissue, characteristic of staged ROP along with flat neovascular syncytium, and characteristic of APROP in the same eye).[18] The procedure was largely conducted in the operating room (OR) (102, 70.3%), under topical anesthesia (134, 86.4%) and in both eyes on the same day (97, 68%) [Fig. 1a-d]. Bevacizumab was the most commonly used agent (85, 54%). However, the majority of the respondents practicing in Government organizations preferred Ranibizumab. Irrespective of the agent of choice, most respondents used half the adult dose (113, 77.9%), which was obtained from a single-use vial (66, 47%) and injected 1–1.5 mm away from the limbus (133, 93%) in the inferotemporal quadrant (55, 38%). Follow-up schedules varied among the members, with 68 (46.5%) reviewing the infant weekly while 53 (36.3%) followed up on the basis of the severity and clinical findings rather than a fixed schedule [Fig. 2a-d].

Figure 1.

(a-d): Indication, anesthetic agent, site for carrying out procedure, eye to be injected; among the respondents. (a): Indications for the use of anti-VEGF in retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). (b): Type of anesthesia preferred for the anti-VEGF injection. (c): Procedure site for the procedure. (d): Protocol for injecting anti-VEGF

Figure 2.

(a-d): Preferred agent, dose, distance from limbus, follow-up schedule; among the respondents. (a): Anti-VEGF of choice for the treatment of ROP. (b): Preferred dose of anti-VEGF. (c): Distance from the limbus for injecting anti-VEGF. (d): Follow-up schedule post-injection

Documentation and monitoring

Photo documentation was used before and after anti-VEGF therapy by 33 (23%) respondents and only 4 (2.8%) performed fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) as part of their management protocol. Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) had issued a ban on the intraocular use of bevacizumab in adults and subsequently revoked the ban. Following this episode, there was a change in the practice pattern of the members in using the drug for ROP with 34 (27.6%) respondents switching over to ranibizumab. A specially drafted consent for anti-VEGF use was used by 89 (62%) respondents. One-hundred fifty one (96.2%) respondents felt the need for guidelines from the iROP society regarding the usage of anti-VEGF in ROP.

Discussion

Anti-VEGF provides an effective and technically simpler alternative to the laser in ROP. In addition, it tends to preserve more functional retina and has been shown to have lesser myopia than laser.[19,20] The major concerns about the use of anti-VEGF for ROP are recurrence of the disease and the possible effect on neurological development.[14,21] The benefits of anti-VEGF in ROP should be weighed against these and other unknown possible risks. Due to wide variation in literature regarding the preferred drug, dosage, effectiveness, recurrence, and systemic adverse effect as well as lack of guidelines about the use of anti-VEFG in ROP, the decision for an ROP practitioner is challenging.

The Indian ROP society is the first, registered, professional body worldwide to enroll ROP specialists nationally. India has over 20,000 ophthalmologists, approximately 2000 vitreoretinal surgeons and just over 200 ROP specialists. This report is the hitherto largest survey result that details the practice patterns of using anti-VEGF therapy for ROP treatment.

Demographics, practice setting, indications, and agent

The age of the respondents or their duration of experience in ophthalmology or respective subspecialties, as well as experience in managing ROP, had no influence on the use of anti-VEGF and preference to a particular agent. However, respondents working in Government hospitals preferred ranibizumab over bevacizumab. This is possibly following the Government advisory on limiting the intraocular use of bevacizumab in adults, making it mandatory to use ranibizumab. In public hospitals, the cost including the pharmaceutical agent is either free or subsidized. Private hospitals, in contrast, have price-sensitive decisions to make for their patients since a majority in India are still not covered under insurance schemes.

The most common indication for the use of anti-VEGF was APROP or hybrid disease; this preference is supported by the relatively poor outcomes after laser monotherapy in APROP as compared to staged ROP.[6,22] For non APROP disease requiring treatment (i.e., Type 1 ROP defined by ETROP), only 8 (5.3%) of the respondents are likely to use anti-VEGF as a primary modality, suggesting that laser therapy is still the gold standard.

In this survey, 137 (87.2%) used anti-VEGF for treating ROP. This is considerably higher than a previously conducted survey of 113 members in 2017, wherein 41% of members had never used anti-VEGF.[5] This indicates the increasing popularity of anti-VEGF as a treatment modality but may also indicate the increase in the number of cases of APROP across the country, especially after the increase in the number of special newborn care units (SNCU) situated in district headquarters.[23] Although ranibizumab is used by a significant proportion (61, 38.8%), the majority of specialists still preferred bevacizumab (85, 54.1%). This may be due to the ease of multiple usage vials, relatively lower cost, and relatively delayed recurrence with bevacizumab. Fouzdar Jain et al.[17] in their survey of pediatric ophthalmologists reported that laser was the preferred modality of treatment and bevacizumab was the preferred anti-VEGF. In a survey from USA, 54% respondents preferred anti-VEGF as a primary modality for the treatment of zone 1 ROP with plus disease and bevacizumab was the preferred agent (78%).[24]

Procedure

Unlike retinal pathologies in adults which are US FDA approved, the use of anti-VEGF in ROP continues to be “off label” and not yet approved. Recently, ranibizumab 0.2 mg was approved by the European Commission for the management of severe ROP.[11] Bevacizumab, the most frequently used anti-VEGF for ophthalmic conditions in adults as well as in infants with severe ROP, has never been approved for intraocular use and remains off label.

Following the ban on intraocular use of bevacizumab by DCGI, 27.6% of respondents switched to ranibizumab for the treatment of infants with ROP, while the majority of the others are still using bevacizumab. The ban was subsequently revoked by DCGI,[25] and a specially drafted consent describing the off label indication and its use, ophthalmic indications and complications or adverse effect has been issued by All India Ophthalmological Society and Vitreo-retinal Society of India. This consent does not include ROP among the list of ophthalmic indications. Among the specialists, 85.3% of the respondents were aware of this fact and 25 (18.6%) respondents are still using the older consent for infants with ROP. Moreover, 56.7% of respondents used specially drafted consent, which describes the use of anti-VEGF as “off label” along with possible long-term risks in preterm infants including neurodevelopmental delay. Subgroup analysis revealed respondents of age more than 40 years of age were using general consent more commonly than those under 40 years (P = 0.02)

Photo documentation

Photo documentation done prior, or on the day of the injection and during subsequent follow-up visits, will serve as an objective documentation to monitor clinical response and also safeguard against future litigation and medico-legal cases. In the current survey, only 21% of the respondents are photo-documenting their cases. This is possibly due to the unavailability of pediatric wide-field digital cameras with most of the respondents. However, with the availability of more affordable cameras that are portable, it is likely to improve the accessibility and utility in the future.[26]

The relatively lower proportion of surgeons using retinal imaging in ROP screening is not unique to India. In a recent survey among the medical directors of level 3 neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in the United States, retinal imaging was performed in 21% of centers only.[27] Furthermore, only 4 (2.8%) respondents in our survey are using FFA after anti-VEGF injection, possibly due to limited availability of the pediatric wide-field cameras compatible with FFA (currently on the RetCam 3, Natus, California, USA, only).

Procedure setting

Safety of intravitreal injection (IVI) for treating ROP in the NICU under topical anesthesia has been reported.[28] The procedure if done in NICU helps in carrying out it under the supervision of neonatologist, with minimal risk of systemic instability like apnea, lowering of oxygen saturation, which might occur while shifting these preterm infants to OR. However, carrying out the procedure in NICU without operating a microscope or loop may increase the chances of injury to crystaline lens. A relatively compromised perioperative asepsis in NICU compared to the OR can increase the risk of intraocular infection as well. In the current survey, though the majority of the respondents (86.4%) performed the procedure under topical anesthesia, a majority (70.3%) still preferred the main OR for the procedure and not the office or the neonatal unit. This might reflect the VRSI or AIOS guidelines for injecting intravitreal bevacizumab (IVB) in adults, which do not recommend it as an office procedure.[29] However, it must be noted that both national societies do not have guidelines for anti-VEGF injections for infants or children.

Eye to be treated

Though the safety of bilateral IVI in adults has been reported in retrospective studies involving thousands of procedures,[30] VRSI and AIOS guidelines for IVB do not recommend a bilateral injection on the same day.[29] ROP usually is bilaterally symmetrical in most cases and therefore injecting both eyes on the same day is logistically more convenient. Furthermore, these infants are often systemically brittle and scheduling and treating the fellow eye on the following day or a few days later may increase the systemic stress to the infant. In babies with both eyes having symmetrical disease, the delay in treating the delayed eye may influence the final outcome. It may thus be logistically justified to inject both eyes on the same day, but we recommend that this must be explained to the parents and mentioned in the special consent. In the current survey, more than two-thirds (67.8%) of the respondents injected IVI in both eyes in the same sitting.

Dose and site

A dose that causes suppression of VEGF to an extent just enough to halt or reverse the formation of abnormal retinal blood vessels without affecting physiological angiogenesis in the retina and other organ systems must be the most important consideration in deciding the appropriate dose of anti-VEGF in ROP. The lower dose has the risk of early recurrence while higher doses may unduly suppress systemic VEGF for a longer time.[13,14] For IVB, the dosage has varied from 0.031 mg to 0.625 mg and success has been reported with all the lower doses as well.[13,31,32] Similarly, for intravitreal ranibizumab (IVR), dosage used has varied from 0.1 mg to 0.25 mg.[11,32,33] Two randomized clinical trials for IVR, RAINBOW and CARE-GROUP, recommended the use of 0.2 mg and 0.12 mg, respectively.[11,33] However, most of the studies have used half the adult dose.[15,31,32,34] In the current survey, 113 (77.9%) respondents used half the adult dose for the procedure, irrespective of the agent used, while 30 (20.7%) respondents used one-third or less of the adult dose. Even lower doses require fractioning or special types of equipment which are not accessible to most ROP specialists.

Infants have poorly differentiated pars plana zone of the ciliary body along with a relatively larger crystalline lens in proportion to the globe size. Thus in infants less than three months of age undergoing pars plana vitrectomy the sclerotomies are made at 1.5 mm from the limbus.[35] However, various studies on IVI in infants with ROP have reported the safety of injection at 1 mm, 1.5 mm as well as 2 mm from the limbus.[10,15,36,37] The current survey shows 51.1% of respondents injecting IVI at 1 mm from the limbus, and a nearly equal number (41.9%) injecting at 1.5 mm from the limbus.

Postoperative follow-up

After IVI of anti-VEGF, it is necessary to have these infants followed up to monitor the possible procedure-related adverse events, regression of the disease, status of vascularization of the immaturity retina, and recurrence of the disease. This follow-up period is likely to be prolonged as late recurrence is common feature in infants treated with anti-VEGF. Recurrence rates have been reported to be more than 50% in various studies for ROP. The recurrence rate is higher in type 1 ETROP with RBZ as compared to BVZ,[38] and almost similar recurrence in APROP with either of the two drugs.[39] The majority of the respondents of the current survey (46.5%) preferred weekly follow-up. However, around one-third (36.3%) of respondents decided their follow-up schedule based on the disease severity. The outer limit of follow-up for these infants was not uniform in the absence of guidelines.

Need for guidelines

With the increasing popularity for using anti-VEGF for ROP treatment and the increasing number of APROP cases, a rise in the use of anti-VEGF therapy is expected. However, due to a wide variability in the literature about the indication, drug, dosage, settings for their usage as well as lack of data on long-term systemic safety profile, the treating ROP specialist is unsure which protocol to follow. In our survey, 96% of the respondents expressed the need for guidelines for the use of anti-VEGF in ROP.

This survey has several strengths including a relatively high response rate, a pan-national coverage, a wide range of experience in subspecialty, and high number of cases being treated by the individual members. The limitations are the fact that the survey was restricted to practicing specialists from India only, who have been influenced by the national guidelines for the use of anti-VEGF for adults by the national society. The ROP screening program in India is similar to other middle-income countries, but different from the western nations making our results not generalizable.[40] Furthermore, we did not enquire about the use of perioperative antibiotic, procedure-related adverse events, an interval of disease recurrence, use of laser as primary or combination therapy, and outcome at the end of follow-up.

Conclusion

Although this survey is not linked or compared with the disease outcome, it represents a strong database of the current practice patterns of various aspects of anti-VEGF used in ROP in India, which is currently the nation with the largest number of preterm infants and is summarized in [Table 1]. These are not guidelines, but in the absence of one, can help to develop one based on this data, along with expert consensus and outcome validation.

Table 1.

Summary of current practice pattern among ROP specialists in India-Suggestions for future Guidelines

| Parameters | Suggestions for Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Indication | APROP in zone 1 |

| Drug Used | Bevacizumab or Ranibizumab |

| Dose | Half or One-third of adult dose |

| Site of Injection | 1-1.5 mm from limbus |

| Place of Injection | Operating room (if sick then Neonatal Unit) |

| Follow-up Schedule | Weekly/Customize depending on the severity and outcome |

Financial support and sponsorship

No financial support to disclose.

Conflicts of interest

None of the above authors has any proprietary interests or conflicts of interest related to this submission.

Acknowledgement

Members of Indian Retinopathy of Prematurity Society for participation in the online survey.

References

- 1.Blencowe H, Moxon C, Gilbert C. Update on blindness due to retinopathy of prematurity globally and in India. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:S89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanghi G, Dogra MR, Katoch D, Gupta A. Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity in infants ≥1500 g birth weight. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62:254–7. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.128639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinekar A, Dogra MR, Sangtam T, Narang A, Gupta A. Retinopathy of prematurity in Asian Indian babies weighing greater than 1250 grams at birth: Ten-year data from a tertiary care center in a developing country. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:331–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.33817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah PK, Narendran V, Kalpana N. Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity in large preterm babies in South India. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F371–5. doi: 10.1136/fetalneonatal-2011-301121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinekar A, Azad R, Dogra MR, Narendran V, Jalali S, Bende P. The Indian retinopathy of prematurity society: A baby step towards tackling the retinopathy of prematurity epidemic in India. Ann Eye Sci. 2017;2:27. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity cooperative group. Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: Results of early treatment for ROP randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1684–96. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Multicenter trial of cryotherapy for retinopathy of prematurity. One-year outcome--structure and function. Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1408–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katoch D, Dogra MR, Aggarwal K, Sanghi G, Samanta R, Handa S, et al. Posterior zone I retinopathy of prematurity: Spectrum of disease and outcome after laser treatment. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn JT, Chan-Ling T. Retinopathy of prematurity: Two distinct mechanisms that underlie zone 1 and zone 2 disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mintz-Hittner HA, Kennedy KA, Chuang AZ BEAT-ROP Cooperative Group. Efficacy of intravitreal Bevacizumab for stage 3+ retinopathy of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stahl A, Lepore D, Fielder A, Fleck B, Reynolds D, Chiang MF, et al. Ranibizumab versus laser therapy for the treatment of very low birth weight infants with retinopathy of prematurity (RAINBOW): An open-label randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1551–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31344-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falavarjani KG, Nguyen QD. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: A review of the literature. Eye (Lond) 2013;27:787–94. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace DK, Dean TW, Hartnett ME, Lingkun K, Smith LE, Hubbard GB, et al. A dosing study of bevacizumab for retinopathy of prematurity: Late recurrences and additional treatments. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:1961–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VanderVeen DK, Melia M, Yang MB, Hutchinson AK, Wilson LB, Lambert SR. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for primary treatment of type 1 retinopathy of prematurity: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:619–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arámbulo O, Dib G, Iturralde J, Brito M, Fortes Filho JB. Analysis of the recurrence of plus disease after intravitreal ranibizumab as a primary monotherapy for severe retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2:858–63. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhr JH, Xu D, Rahimy E, Hsu J. Current practice preferences and safety protocols for intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3:649–55. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouzdar Jain S, Song HH, Al-Holou SN, Morgan LA, Suh DW. Retinopathy of prematurity: Preferred practice patterns among pediatric ophthalmologists. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1003–9. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S161504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanghi G, Dogra MR, Dogra M, Katoch D, Gupta A. A Hybrid form of retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:519–22. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the negative outcomes of retinopathy of prematurity treated with laser photocoagulation. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019;29:223–8. doi: 10.1177/1120672118770557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sankar MJ, Sankar J, Chandra P. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD009734. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009734.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sankar MJ, Sankar J, Mehta M, Bhat V, Srinivasan R. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009734. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009734.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanghi G, Dogra MR, Katoch D, Gupta A. Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity: Risk factors for retinal detachment despite confluent laser photocoagulation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:159–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinekar A, Jayadev C, Mangalesh S, Shetty B, Vidyasagar D. Role of tele-medicine in retinopathy of prematurity screening in rural outreach centers in India-A report of 20,214 imaging sessions in the KIDROP program. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20:335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tawse KL, Jeng-Miller KW, Baumal CR. Current practice patterns for treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016;47:491–5. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20160419-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A, Tripathy K, Chawla R. Intraocular use of Bevacizumab in India: An issue resolved? Natl Med J India. 2017;30:345–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-258X.239079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinekar A, Dogra MR, Shetty B. Imaging the ora serrata with the 3Nethra Neo camera-Importance in screening and treatment in retinopathy of prematurity. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:270–1. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1232_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vartanian RJ, Besirli CG, Barks JD, Andrews CA, Musch DC. Trends in the screening and treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20161978. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercado HQ, Guerrero-Naranjo JL, Aguirre GG, Ernst BJ, Patel CC, Chan PR, et al. Methods and techniques for intravitreal antiangiogenic therapy (IAT) in retinopathy of prematurity (ROP): A 196 cases experience. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3169. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar A, Verma L, Aurora A, Saxena R. AIOS-VRSI guidelines for intravitreal injections. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: http://aios.org/avguidelines.pdf .

- 30.Tandon M, Vishal MY, Kohli P, Rajan RP, Ramasamy K. Supplemental laser for eyes treated with bevacizumab monotherapy in severe retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2:623–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hillier RJ, Connor AJ, Shafiq AE. Ultra-low-dose intravitreal Bevacizumab for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: A case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:260–4. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen SN, Lian I, Hwang YC, Chen YH, Chang YC, Lee KH, et al. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for retinopathy of prematurity: Comparison between Ranibizumab and Bevacizumab. Retina. 2015;35:667–74. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stahl A, Krohne TU, Eter N, Oberacher-Velten I, Guthoff R, Meltendorf S, et al. Comparing alternative ranibizumab dosages for safety and efficacy in retinopathy of prematurity (CARE-ROP) study group: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Paediatr. 2018;172:278–86. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon JM, Shin DH, Kim SJ, Ham DI, Kang SW, Chang YS, et al. Outcomes after laser versus combined laser and bevacizumab treatment for type 1 retinopathy of prematurity in zone I. Retina. 2017;37:88–96. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan SJ, Schachat AP, Wilkinson CP. Ryan's retina. In: Meier P, Wiedemann P, editors. In Surgery for Pediatric Vitreoretinal Disorders. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 2170–93. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padhi TR, Das T, Rath S, Pradhan L, Sutar S, Panda KG, et al. Serial evaluation of retinal vascular changes in infants treated with intravitreal Bevacizumab for aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity in zone I. Eye (Lond) 2016;30:392–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ells AL, Wesolosky JD, Ingram AD, Mitchell PC, Platt AS. Low-dose Ranibizumab as primary treatment of posterior type I retinopathy of prematurity. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52:468–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyu J, Zhang Q, Chen CL, Xu Y, Ji XD, Li JK, et al. Recurrence of retinopathy of prematurity after intravitreal ranibizumab monotherapy: Timing and risk factors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:1719–25. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blair M, Gonzalez JM, Snyder L, Schechet S, Greenwald M, Shapiro M, et al. Bevacizumab or laser for aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2018;8:243–8. doi: 10.4103/tjo.tjo_69_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Project operational guidelines. Prevention of Blindness from Retinopathy of Prematurity in Neonatal Care Units. [Last accessed on 2019 May 21]. Available from: https://phfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2018-ROPoperational-guidelines.pdf .