Abstract

Background.

Benzodiazepine (BZD)-related overdose deaths have risen in the past decade and BZD misuse contributes to thousands of emergency department (ED) visits annually, with the highest rates in adolescents and young adults. Because there are gaps in understanding BZD poisoning in youth and whether differences occur by sex, we aimed to characterize BZD poisonings ED visits in young people by sex.

Methods.

BZD poisoning visits were identified in the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, among adolescents (12–17 years) and young adults (18–29 years). Stratified by sex and age, we described ED visits for BZD poisonings in 2016, including poisoning intent, concurrent substances involved, and co-occurring mental health disorder diagnoses. With logistic regression we examined the association between intent and concurrent substance.

Results.

There were approximately 38,000 BZD poisoning ED visits by young people nationwide with annual population rates per 10,000 of 2.9=adolescents and 5.8=young adults. Depression was diagnosed in 40% of female and 23% of male BZD visits (p<0.01). Over half of BZD poisonings in females and a third in males were intentional (p<0.01). Male BZD visits were more likely to involve opioids or cannabis and less likely to involve antidepressants than females (p-values<0.01). In males and females, BZD poisonings concurrent with antidepressants and other psychotropic medications were more likely to be intentional than unintentional (OR range:2.1–6.3).

Conclusions.

The high proportion of BZD poisonings that are intentional and include mental health disorder diagnoses, especially among young females, underscore the importance of ED mental health and suicide risk assessment with appropriate follow-up referral.

Keywords: Benzodiazepine, Poisoning, Emergency Department, Sex, Adolescents

1. Introduction

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are central nervous system depressants and rank second, after prescription opioids, among prescription drugs involved in overdose deaths.(Jones, Mack, and Paulozzi 2013) BZDs were involved in 10,724 overdose deaths (16% of all overdose deaths) in the US in 2018 up from 6,973 five years earlier.(National Institute on Drug Abuse) Annually, BZD poisoning or misuse contributes to thousands of hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits.(Coben et al. 2010; Jones and McAninch 2015; Cai et al. 2010; Jones et al. 2014; Geller et al. 2019; Moro et al. 2020) BZD-related ED visits increased from 2004 to 2011,(Jones and McAninch 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2014) with a decline in the rate of nonfatal ED visits for BZD overdoses from 2016 to 2017 to an annual population-level rate of 36 per 100,000 persons.(Vivolo-Kantor et al. 2020)

Adolescents and young adults saw the highest rates of ED visits for adverse events due to BZD misuse from 2016–2017;(Moro et al. 2020) similar to earlier research in which ED visits for BZD misuse peaked in young adults.(Cai et al. 2010) BZDs are often misused by young people(McCabe, Wilens, et al. 2019; Maust, Lin, and Blow 2019; McCabe, Veliz, et al. 2019) with 8% of high-school seniors reporting prior BZD misuse(McCabe and West 2014) and young adult BZD users have an increased risk for BZD misuse and use disorders compared to older adults.(Blanco et al. 2018) Further, the rate of drug overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines rose from 0.1 in 2000 to 0.6 in 2015 in adolescents (15–19 years),(Curtin, Tejada-Vera, and Warmer 2017) making adolescence and young adulthood important periods in which to characterize BZD related harms.

Moro et al. recently highlighted ED visits for BZD adverse events in all ages; however, there remain gaps in understanding BZD poisonings in youth and, with ED visits for BZD poisonings more frequent in females,(Kaufmann et al. 2017; Brown et al. 2018; Vivolo-Kantor et al. 2020) what sex differences may occur by intent, concurrent substances, and associated mental disorder diagnoses.

Approximately half (54–56%) of all BZD poisoning ED visits are intentional, 28–30% unintentional, and 14–19% therapeutic use or other;(Xiang et al. 2012; Moro et al. 2020) intentional BZD poisonings are more common in females.(Moro et al. 2020) Among adolescents who died from drug overdose, deaths are proportionally more likely to be intentional in females (22%) than in males (9%).(Curtin, Tejada-Vera, and Warmer 2017) Describing the intent of nonfatal BZD poisonings in specifically in young males and females can inform ED management and follow-up care in this population.

Opioids and alcohol are commonly involved in BZD-related overdose deaths and ED visits,(Jones et al. 2014; Warner et al. 2016) with concurrent substances varying by intent of BZD adverse event.(Moro et al. 2020) Drug mixtures in intentional drug overdoses also vary substantially between youth and adults.(Miller et al. 2020) Concurrent substances involved in youth BZD overdoses likely also vary by sex given sex differences in substance use, with higher illicit drug use and alcohol use in young adult males than females.(Schulenberg JE 2018)

Recent emphasis has focused on ED visits for opioid overdoses; however, to help reduce drug mortality, attention should also be paid to overdoses that involve BZDs.(Goldman-Mellor et al. 2020) An improved understanding of BZD poisoning ED visits in adolescents and young adults, and how they differ between males and females, will help focus BZD poisoning prevention efforts and inform follow-up mental health and substance use service planning. Therefore, in adolescents and young adults we aimed to characterize ED visits for BZD poisonings by sex, through a) estimating the national ED visit rate for BZD-related poisonings, b) describing concurrent substances involved in the BZD poisoning and the intent of BZD poisoning, and c) determining how concurrent substances are associated with the recorded intent of the BZD poisoning.

2. Methods

2.1. Datasource & study design.

We used data from the 2016 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.(Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project 2020) The NEDS tracks information on ED visits across the United States, including visits for individuals discharged or admitted to hospitals. The dataset combines the HCUP State Emergency Department Databases (SEDD), which captures discharge information on ED visits not resulting in admission, and the State Inpatient Databases (SID), which captures patients seen in the ED and then admitted to the same hospital. The NEDS is an all-payer ED database containing 33 million ED visits in 2016 at 953 hospitals across 36 states and the District of Columbia.(Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2019) Weights are provided to yield national estimates of ED visits. Patient, geographic, and hospital characteristics along with the nature and reason of the ED visit are collected. Our analysis was restricted to BZD poisoning ED visits by adolescents (12–17 years) and young adults (18–29 years) in 2016 (n=8,703 unweighted).

2.2. BZD poisoning.

We defined BZD poisoning ED visits as those with an ICD-10-CM code, in any diagnostic position, for: unintentional (T42.4X1), intentional self-harm (T42.4X2), and undetermined (T42.4X4) BZD poisonings and adverse effect of BZDs (T42.4X5). Underdosing of BZDs (T42.4X6) and BZD poisonings due to assault (T42.4X3) were not included.

2.3. Concurrent active substance(s).

We identified concurrent substances involved with the BZD poisoning ED visit through the following ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes: T36.x–T50.x (poisoning by, adverse effect of and underdosing of drugs, medicaments and biological substances; excluding T42.4x), T51.x–T65.x (toxic effects of substances chiefly nonmedicinal as to source), Y90.x (evidence of alcohol involvement determined by blood alcohol level), and diagnostic codes for substance abuse, dependence, or unspecified ‘with intoxication’ (F10–F12, F14–F16, F18–F19 codes ending in .12x, .22x, or .92x). Substance abuse or dependence codes without ‘intoxication’ specification were not included in our definition of concurrent active substances as we cannot confirm these substances were involved in the poisoning event.

2.4. Additional variables.

To describe BZD poisoning ED visits, we identified patient age, sex, disposition at discharge, death in the ED or hospital, median household income for patient’s county of residence, patient county size, and expected primary payer. We identified mental health disorder diagnoses and substance use disorder diagnoses that were also listed on the BZD poisoning ED visit record; these diagnoses were defined based on ICD-10-CM codes (eTable 1).

2.5. Statistical analysis.

For our descriptive analysis, we estimated the number of nationwide ED visits for BZD poisonings in 2016 applying discharge weights(Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2019) and calculated the rate of BZD poisoning ED visits per 10,000 ED visits. Rates were stratified by sex and age; population-level rates were estimated using US census data. We described the intent and concurrent substances in BZD poisoning ED visits stratified by sex. We examined associations between each concurrent substance and BZD intent (intentional self-harm vs. unintentional) with logistic regression, estimating crude and multivariable odds ratios (OR) of the likelihood a BZD poisoning was intentional by the concurrent substance involved. We included age, sex, and common mental health diagnoses as covariates in the multivariable model. This analysis was restricted to BZD poisonings coded as intentional or unintentional and completed overall and stratified by sex. Presented 95% CI estimates and p-values account for NEDS sampling design.(Houchens R, Ross D, and Elixhauser A 2015; Huang et al. 2017; Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2019)

2.6. Sensitivity analyses.

For a first sensitivity analysis, we restricted the sample to ED visits in which BZD poisoning was the principal/first listed diagnosis. The principal diagnosis is defined as the condition chiefly responsible for the visit. In a second sensitivity analysis, we estimated how many BZD poisoning events may be classified under related unspecified/broad ICD-10-CM diagnostic category. Here we examined the additional number of ED visits with a diagnosis of a poisoning or adverse effect from an unspecified antiepileptic or sedative, hypnotic drug (T42.7) and the number of visits with a diagnosis for sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic abuse with intoxication (F13.12), dependence with intoxication (F13.22), or unspecified with intoxication (F13.92). The study was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

3.1. Rate of youth BZD poisoning ED visits by sex.

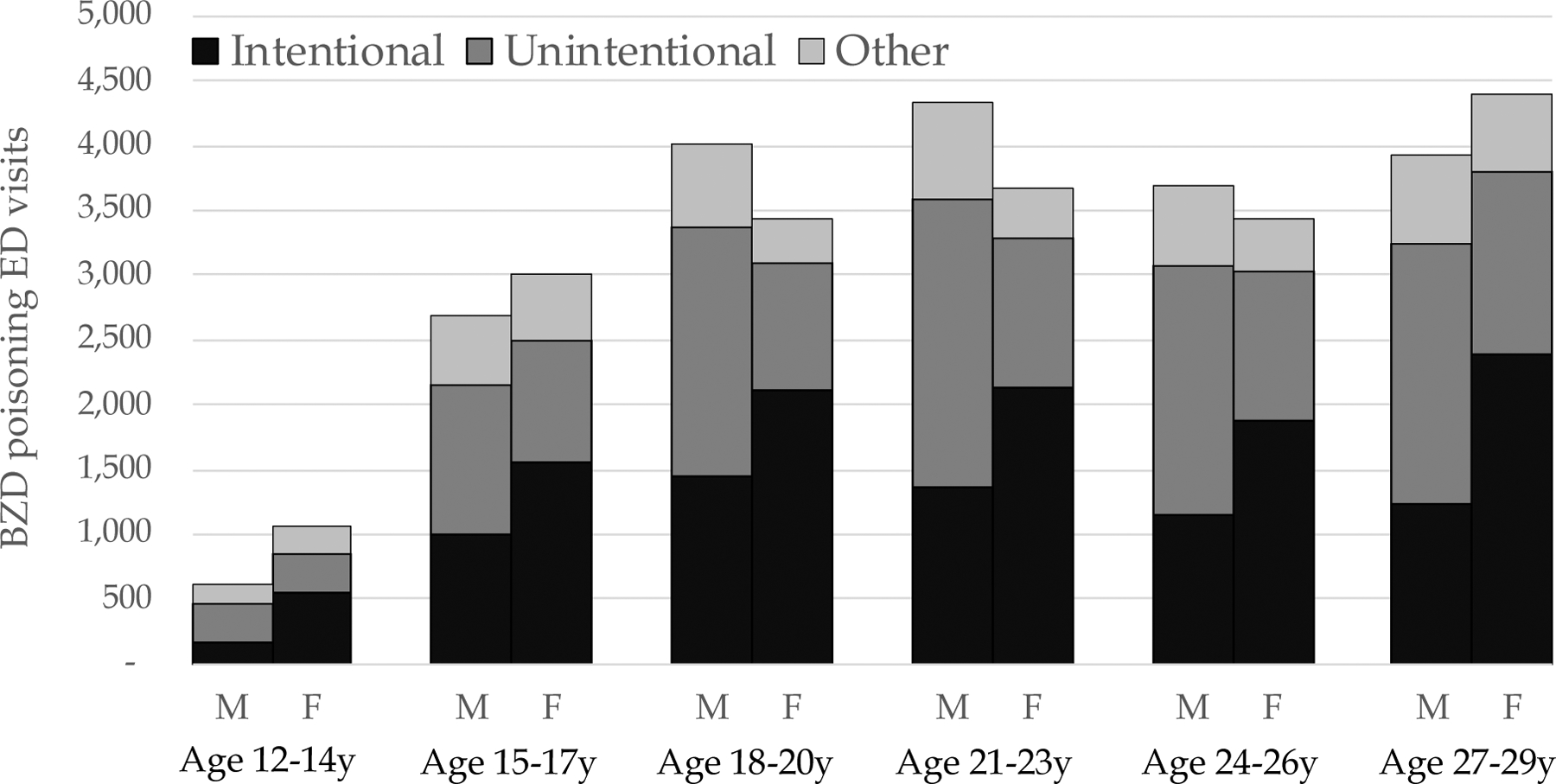

We identified 8,703 ED visits for BZD poisonings in adolescents and young adults (12–29 years) in 2016, for a weighted, nationwide estimate of 38,308. BZD-poisoning ED visits increased from age 12 to 18 years and were fairly stable during young adulthood (Figure 1). The rate of BZD-poisoning ED visits per 10,000 population was 2.9 for adolescents and slightly higher for females (3.3) than males (2.6). In young adults the population rate was 5.8 per 10,000 and similar for females (5.7) and males (5.8) (eTable 2).

Figure 1. Benzodiazepine poisoning emergency department visits by females and males by recorded intention, United States 2016.

F: Female; M: Male; y: years

2016 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS); counts are weighted to emergency department (ED) visits for the US population

3.2. Disposition and mental health diagnoses.

Most BZD poisoning ED visits were treat-and-release, still 28% of adolescents and 42% of young adults were admitted or transferred to a hospital (Table 1). Mental health or substance use disorder diagnoses were recorded on most ED visits for BZD poisonings by males and females (Table 1). Substance use disorders were more common in male BZD poisoning ED visits than females. In young adult male BZD poisoning ED visits, 14% had an opioid use disorder diagnosis and 17% a cannabis disorder diagnosis. By contrast, mental health diagnoses were more common in BZD poisonings in females (adolescents: 49%; young adults: 67%) than in males (adolescents: 37%; young adults: 48%). Depression was the most common mental health diagnosis and was more common in female (40%) than male (23%) visits.

Table 1.

Characteristics of adolescent and young adult benzodiazepine poisoning ED visits by sex: United States, 2016

| Adolescents, 12–17 years | Young adults, 18–29 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| No. (%)a | No. (%)a | No. (%)a | No. (%)a | |

| Total | 3,315 | 4,065 | 15,978 | 14,950 |

| Principle diagnosis: BZD poisoning | 2,389 (72.1) | 2,681 (66.0)^ | 8,859 (55.4) | 8,310 (55.6) |

| Died in ED or hospital | * | * | 154 (1.0) | 69 (0.5)^ |

| Outcome of ED visit | ||||

| Treat and release | 2,491 (75.1) | 2,813 (69.2)^ | 9,324 (58.4) | 8,513 (56.9) |

| Admitted to same hospital | 591 (17.8) | 826 (20.3) | 6,043 (37.8) | 5,648 (37.8) |

| Transferred to another short-term hospital | 230 (6.9) | 415 (10.2)^ | 509 (3.2) | 736 (4.9)^ |

| Other (patient not admitted, died in ED) | * | * | 102 (0.6) | 53 (0.4) |

| Diagnoses at ED visit | ||||

| Any mental health or substance use disorder | 1,907 (57.5) | 2,416 (59.4) | 12,449 (77.9) | 12,285 (82.2)^ |

| Any mental health disorder | 1,218 (36.7) | 1,973 (48.5)^ | 7,694 (48.2) | 10,002 (66.9)^ |

| Depression | 698 (21.1) | 1,443 (35.5)^ | 3,797 (23.8) | 6,219 (41.6)^ |

| Anxiety disorder | 360 (10.9) | 780 (19.2)^ | 3,626 (22.7) | 5,118 (34.2)^ |

| Other mood disorder | 98 (3.0) | 249 (6.1)^ | 1,749 (10.9) | 2,150 (14.4)^ |

| Other mental health disorder | 589 (17.8) | 614 (15.1) | 2,917 (18.3) | 3,506 (23.5)^ |

| Any substance use disorder (excluding nicotine) | 1,031 (31.1) | 809 (19.9)^ | 7,990 (50.0) | 5,689 (38.1)^ |

| Alcohol use disorder | 201 (6.1) | 182 (4.5) | 2,864 (17.9) | 2,321 (15.5)^ |

| Sedative/anxiolytic use disorder | 236 (7.1) | 124 (3.1)^ | 1,651 (10.3) | 847 (5.7)^ |

| Opioid use disorder | 70 (2.1) | 52 (1.3) | 2,182 (13.7) | 1,281 (8.6)^ |

| Cannabis use disorder | 544 (16.4) | 448 (11.0)^ | 2,657 (16.6) | 1,627 (10.9)^ |

| Stimulant use disorder | 117 (3.5) | 84 (2.1) | 1,605 (10.0) | 1,139 (7.6)^ |

| Nicotine dependence | 383 (11.6) | 325 (8.0)^ | 5,519 (34.5) | 4,294 (28.7)^ |

| Expected primary payer b | ||||

| Medicaid | 1,605 (48.4) | 1,751 (43.1) | 4,935 (30.9) | 5,401 (36.1)^ |

| Private insurance | 1,351 (40.7) | 1,909 (47.0)^ | 6,151 (38.5) | 6,044 (40.4) |

| Self-pay | 232 (7.0) | 249 (6.1) | 3,655 (22.9) | 2,299 (15.4)^ |

| Other (Medicare, no charge, other) | 124 (3.7) | 156 (3.8) | 1,199 (7.5) | 1,189 (8.0) |

| Median household income of patient zip code c | ||||

| <43,000 | 898 (27.1) | 980 (24.1) | 3,845 (24.1) | 4,225 (28.3)^ |

| 43,000 to <54,000 | 825 (24.9) | 908 (22.3) | 4,025 (25.2) | 3,919 (26.2) |

| 54,000 to <71,000 | 760 (22.9) | 1,032 (25.4) | 3,749 (23.5) | 3,468 (23.2) |

| 71,000+ | 781 (23.6) | 1,089 (26.8) | 3,938 (24.6) | 3,099 (20.7)^ |

| Patient county size d | ||||

| Large metropolitan (1+ million) | 1,292 (39.0) | 1,558 (38.3) | 4,594 (28.8) | 4,028 (26.9) |

| Fringe of large metropolitan | 632 (19.1) | 899 (22.1) | 4,064 (25.4) | 3,170 (21.2) |

| Mid-sized metropolitan (250,000 to <1 million) | 663 (20.0) | 813 (20.0) | 3,407 (21.3) | 3,726 (24.9) |

| Small metropolitan (50,000 to <250,000) | 283 (8.6) | 275 (6.8) | 1,664 (10.4) | 1,601 (10.7) |

| Micropolitan | 292 (8.8) | 284 (7.0) | 1,415 (8.9) | 1,351 (9.0) |

| Not metropolitan or micropolitan | 153 (4.6) | 223 (5.5) | 627 (3.9) | 973 (6.5)^ |

BZD: benzodiazepine; ED: emergency department

Small cell count; numbers not presented

P-value comparing males and females <0.05

Presented numbers are weighted

Missing expected primary payer: 0.1% of total

Missing median household income: 2.0% of total

Missing patient county size: 0.8% of total

3.3. Intent of BZD poisoning.

Overall, 44% of BZD-poisoning ED visits were recorded as intentional (Table 2; Figure 1). A greater proportion of BZD poisoning ED visits by females (adolescents: 51%; young adults: 57%) than by males (adolescent: 35%; young adults: 32%) were intentional self-harm.

Table 2.

Intent of and concurrent substances in benzodiazepine poisoning ED visits by adolescents and young adults by sex: United States, 2016

| Adolescents, 12–17 years | Young adults, 18–29 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| No. (%)a | No. (%)a | No. (%)a | No. (%)a | |

| Recorded intent of BZD poisoning | ||||

| Intentional self-harm | 1,160 (35.0) | 2,090 (51.4)^ | 5,186 (32.5) | 8,525 (57.0)^ |

| Unintentional | 1,470 (44.3) | 1,254 (30.8)^ | 8,092 (50.6) | 4,668 (31.2)^ |

| Undetermined | 359 (10.8) | 264 (6.5)^ | 1,161 (7.3) | 767 (5.1)^ |

| Adverse effect | 327 (9.9) | 458 (11.3)^ | 1,539 (9.6) | 991 (6.6)^ |

| Concurrent substance b | ||||

| Any non-BZD poisoning or intoxication | 1,025 (30.9) | 1,409 (34.7) | 8,406 (52.6) | 8,014 (53.6) |

| Alcohol | 187 (5.6) | 172 (4.2) | 2,259 (14.1) | 2,023 (13.5) |

| Opioid (any)c | 304 (9.2) | 229 (5.6)^ | 3,694 (23.1) | 2,315 (15.5)^ |

| Cocaine, LSD, other hallucinogen | 91 (2.8) | 83 (2.0) | 1,000 (6.3) | 471 (3.1)^ |

| Cannabis | 258 (7.8) | 161 (4.0)^ | 1,117 (7.0) | 484 (3.2)^ |

| Psychostimulant | 61 (1.8) | 95 (2.3) | 856 (5.4) | 639 (4.3) |

| Psychotropic drug | ||||

| Sedative, hypnotic, antiepileptic | 64 (1.9) | 148 (3.7)^ | 644 (4.0) | 1,081 (7.2)^ |

| Antidepressant | 106 (3.2) | 319 (7.9)^ | 601 (3.8) | 1,379 (9.2)^ |

| Other psychotropic | 63 (1.9) | 154 (3.8)^ | 770 (4.8) | 1,027 (6.9)^ |

| Other drug, medicine, or biological substance | 333 (10.0) | 604 (14.9)^ | 1,329 (8.3) | 2,171 (14.5)^ |

BZD: benzodiazepine; ED: emergency department

Small cell count; numbers not presented

P-value comparing males and females <0.05

Presented numbers are weighted

Other psychoactive substance: adolescents (small cell counts); young adults (males=0.6%, females=0.6%); other nonmedical substance: adolescents (small cell counts), young adults (males=0.9%, females=0.7%)

Heroin, opium: adolescents (small cell counts), young adults (males=8.9%, females=4.5%); Unspecified/other narcotics: adolescents (small cell counts), young adults (males=3.8%, females=2.4%); Opioid other: adolescents (males=7.3%, females=4.0%), young adults (males=11.6%, females=9.2%)

3.4. Concurrent substances involved in BZD poisoning.

A third of adolescent and half of young adult BZD-poisoning ED visits involved a concurrent substance, with variation in substance by age and sex (Table 2). Alcohol was involved in few adolescent BZD poisonings. Opioids were involved in 23% of BZD poisonings in young adult males. A higher proportion of BZD poisoning visits by females involved another psychotropic medication (adolescents: 12%; young adults: 20%) than by males (adolescents: 6%; young adults: 10%).

3.5. Association between intent and concurrent substance.

In males and females, BZD poisonings concurrent with other psychotropic medications were more likely to be intentional self-harm poisonings than unintentional (Table 3). In young adults, alcohol was associated with an increased likelihood of intentional self-harm (aOR:1.33, 95%CI: 1.14–1.56), with no association in adolescents. BZD poisonings in young adults involving cannabis (aOR:0.32, 95%CI:0.24–0.45) or opioids (aOR:0.29, 95%CI:0.24–0.34) were more likely to be unintentional poisonings; in adolescent males, BZD poisonings involving opioids were more likely to be intentional (aOR:2.30, 95%CI:1.29–4.10), eTable 3.

Table 3.

Association between concurrent substance (poisoning or intoxication) and likelihood of an intentional vs. unintentional benzodiazepine poisoning

| Odds of intentional BZD poisoning vs. unintentional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents, 12–17 years | Young adults, 18–29 years | |||

| OR | aOR* (95% CI) | OR | aOR* (95% CI) | |

| Any concurrent substance | 2.19 | 1.86 (1.43–2.42) | 0.93 | 0.84 (0.74–0.96) |

| Alcohol | 0.72 | 0.80 (0.45–2.21) | 1.30 | 1.33 (1.14–1.56) |

| Opioid | 1.35 | 1.33 (0.86–2.06) | 0.26 | 0.29 (0.24–0.34) |

| Cocaine, LSD, other hallucinogen | 0.92 | 1.00 (0.51–1.98) | 0.28 | 0.32 (0.24–0.45) |

| Cannabis | 0.44 | 0.57 (0.33–0.98) | 0.27 | 0.32 (0.24–0.45) |

| Psychostimulant | 2.40 | 2.25 (1.06–4.79) | 0.51 | 0.55 (0.41–0.73) |

| Psychotropic drug | ||||

| Sedative, hypnotic, antiepileptic | 2.25 | 1.60 (0.80–3.21) | 2.59 | 2.09 (1.60–2.72) |

| Antidepressant | 8.21 | 6.27 (2.78–14.17) | 6.47 | 4.23 (3.02–5.93) |

| Other psychotropic | 5.49 | 4.43 (1.62–12.07) | 2.73 | 2.08 (1.58–2.72) |

| Other drug, medicine, or biological | 4.93 | 4.05 (2.64–6.22) | 2.70 | 2.01 (1.65–2.44) |

BZD: benzodiazepine; ED: emergency department; OR: odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio OR above 1: increased likelihood BZD poisoning was recorded as intentional self-harm (vs. unintentional) by that particular concurrent substance

Adjusted for age, sex, mental health diagnoses (depression, other mood, anxiety, other mental health diagnosis)

3.6. Sensitivity analyses.

In the sensitivity analysis restricted to ED visits with BZD-poisoning as the principal diagnosis, there was a lower proportion of BZD poisonings in which a concurrent substance was involved (eTable 4). The proportion of BZD-poisonings that were intentional was consistent when restricting to ED visits with BZD poisoning as the principal diagnosis. Few additional ED visits were added when including unspecified/broad sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic poisoning-related codes (eTable 2 footnote).

4. Discussion

In 2016, there were approximately 38,000 ED visits related to BZD poisonings in adolescents and young adults, with a population-level rate consistent with prior research.(Vivolo-Kantor et al. 2020) BZD poisoning visit rates were similar in female and male young adults and slightly higher in female than in male adolescents, which was primarily driven by more intentional BZD poisonings in females. There was heterogeneity in intentionality, concurrent substance involvement, and mental health and substance use disorders by age and sex. Specifically, intentional self-harm was proportionately more likely in female than male BZD poisoning visits, concurrent substances were involved in a higher proportion of young adult than adolescent poisoning visits, and substance use disorders were more common in male BZD poisoning visits while mental health disorders were more common in female visits.

Both prescribed BZDs and BZD misuse contribute to BZD poisoning events. BZDs are commonly prescribed to treat mental health disorders and are prescribed more frequently to females.(Agarwal and Landon 2019) An estimated one in four adolescents prescribed BZDs later misuses them, with higher BZD misuse reported in females.(McCabe and West 2014) When deciding to prescribe BZDs, providers should consider the patient’s risk of misuse(U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2020) and youth receiving BZD treatment should be closely monitored for prescription misuse.(McCabe and West 2014) Among adolescents reporting prescription drug misuse, a third report using leftover medications from prior prescriptions, which was more common among females.(McCabe, Veliz, et al. 2019) The dosage and duration of the BZD prescription should be limited to that necessary to achieve the desired clinical effect.(U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2020) On September 23, 2020 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced a planned update to the Boxed Warning for BZDs on the potential for misuse, abuse, addiction, and other risks.(U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2020) The updated warning may increase patient and provider education on the potential for adverse risks with BZD treatment.

In the present analyses, we cannot determine whether the poisonings involved BZDs that were prescribed and whether the BZDs were prescribed for a mental health disorder. In North Carolina drug overdose deaths involving alprazolam, 70% of decedents with intentional and 43% with unintentional overdoses had alprazolam prescriptions dispensed in the 30 days before death.(Austin et al. 2017) Similarly, in West Virginia, persons with fatal unintentional drug overdose involving BZD, half had past BZD prescriptions.(Toblin et al. 2010) Given many BZD-involved overdose fatalities involve recent BZD prescriptions, contacts with the healthcare system may provide opportunities for preventing BZD-related overdoses.(Austin et al. 2017)

A concurrent substance was involved in half of BZD-poisoning visits in young adults and in a third of adolescents, with variation in substance by sex. In other reports from all ages, a majority (>80%) of ED visits for BZD misuse involved another substance.(Geller et al. 2019; Moro et al. 2020) The risk of death or harmful outcomes is heightened when BZDs are combined with other substances such as opioids, alcohol, or illicit substances with most BZD fatal overdoses involving an opioid.(National Institute on Drug Abuse) Male BZD poisonings, especially in young adults, were more likely to involve opioids or illicit drugs. Given the risk of death with concurrent opioid and BZD use, in 2016 a Boxed Warning was added for combination BZD and opioid use,(U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2016) which was followed by declines in co-prescribing of opioids and BZDs.(Zhang, Olfson, and King 2019)

Educating patients on the potential harms of mixing BZDs with other depressants such as alcohol and opioids is warranted for youth prescribed BZDs, but also for youth not prescribed BZDs given reported rates of BZD misuse in youth.(McCabe and West 2014) Initial exposure to alcohol and drugs often occurs in adolescence along with opportunities for nonmedical prescription drug use.(McCabe et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2006; Conway et al. 2016) This exposure is coupled with increases in risk-taking behaviors in adolescence.(Sawyer et al. 2012; Patton et al. 2016) As such, adolescence and young adulthood present a unique risk period in the development of substance use problems. Screening adolescents and young adults for alcohol and drug use (Kelly et al. 2014; National Institute on Drug Abuse 2019) may help identify youth needing intervention, and in those receiving BZDs, it may suggest a therapeutic alternative to prescribing BZDs.

Half of BZD-poisoning ED visits by adolescent and young adult females, and a third by males, were intentional. Substances used in intentional poisonings tend to include substances more readily available to that age group.(Spiller et al. 2020; Miller et al. 2020) There is an elevated risk of suicide following ED visits for sedative/hypnotic overdoses.(Goldman-Mellor et al. 2020) This elevated risk, along with the proportion of BZD poisonings that are intentional, place young people with BZD poisoning ED visits, particularly young females, in a high-risk group requiring appropriate suicide risk assessment during ED visits and follow-up referral. In high-risk ED patients, suicide risk screening together with provision of follow-up resources and post-ED telephone calls reduces suicidal behavior following ED discharge.(Miller et al. 2017) With BZDs consistently involved in intentional suicide attempts, a validated tool for self-harm risk in BZD users is warranted.(Moro et al. 2020)

Most youth with BZD-poisoning ED visits had a mental health or substance use disorder diagnosis, with depression the most common mental health diagnosis. BZD users typically have higher prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders than non-BZD users; thus, BZD users are recommended to be assessed on an ongoing basis for psychiatric conditions.(Blanco et al. 2018) Many youth do not receive necessary treatment for these conditions; less than half of youth with major depression received treatment in the past year(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2019) and the vast majority of substance use disorders go untreated in young people.(Haughwout et al. 2016) Further, few youth receive timely addiction treatment following an opioid overdose.(Alinsky et al. 2020) In the high-risk youth presenting to the ED for BZD poisonings, evaluating current management of mental health and substance use disorders and linking youth with resources upon discharge may help alter the future trajectory for these youth.

There are limitations to this research. Our count of BZD-poisoning ED visits is likely an underestimation. BZD involvement in overdose or poisoning events may go unrecognized or unreported when secondary to another substance. In turn, our BZD poisoning definition may include other adverse effects. We likely underestimated concurrent substances involved in BZD poisoning ED visits. This may be due to concurrent substances being undetected during ED visits, unreported by patients, or unrecorded in medical records. Further, we did not include substance abuse/dependence codes without the ‘intoxication’ specification in our definition of concurrent substances. We assessed BZD-poisoning ED visits in US youth; however, rates of BZD-poisonings likely vary substantially across regions, given state variation in BZD prescribing.(Paulozzi, Mack, and Hockenberry 2014) Mental health and substance use disorders are based on diagnoses received on the ED visit record; we do not have information on prior diagnoses. The recorded intent of the BZD-poisoning could potentially be misclassified. We cannot determine whether BZDs, or concurrent substances, were from prescriptions to the patient or were illicitly acquired, which would inform prevention efforts. We used a visit-level dataset that does not permit un-duplication of individuals.

ED visits for BZD poisonings are prevalent in young people and commonly involve suicidal intent, especially in females. Following ED discharge, young people with sedative-hypnotic overdoses are at an increased short-term risk of unintentional fatal overdose and suicide.(Goldman-Mellor et al. 2020) Given the high proportion of intentional BZD poisonings and the proportion with a corresponding mental health disorder or substance use disorder diagnosis, it is critically important to provide these young people with appropriate follow-up care upon ED discharge. Further, since many BZD-related ED visits and deaths involved concurrent substances, screening and addressing substance use, as well as screening for suicidal symptoms, in young people prescribed BZD treatment may improve outcomes. By detailing BZD poisonings in young males and females, we hope to inform efforts to prevent future BZD poisoning events and to target follow-up behavioral healthcare.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

To help reduce drug mortality, attention should also be paid to BZD-related overdoses

Half of BZD poisonings in young (12–29) females and a third in males were intentional

Most BZD poisonings involved mental health or substance use disorder diagnoses

BZD poisonings in youth commonly involved another substance (33–53%)

Sex differences in BZD poisonings occur by intent, concurrent substances, and diagnoses

Acknowledgements.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Bethesda, MD) under Award Numbers T32MH013043 and R01DA045872.

Financial Disclosures.

Dr. Bushnell received support from the National Institute of Mental Health under Award Number T32MH013043. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Role of Funding Source.

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agarwal SD, and Landon BE. 2019. ‘Patterns in Outpatient Benzodiazepine Prescribing in the United States’, JAMA Netw Open, 2: e187399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alinsky RH, Zima BT, Rodean J, Matson PA, Larochelle MR, Adger H Jr., Bagley SM, and Hadland SE. 2020. ‘Receipt of Addiction Treatment After Opioid Overdose Among Medicaid-Enrolled Adolescents and Young Adults’, JAMA Pediatr, 174: e195183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin AE, Proescholdbell SK, Creppage KE, and Asbun A. 2017. ‘Characteristics of self-inflicted drug overdose deaths in North Carolina’, Drug Alcohol Depend, 181: 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Han B, Jones CM, Johnson K, and Compton WM. 2018. ‘Prevalence and Correlates of Benzodiazepine Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders Among Adults in the United States’, J Clin Psychiatry, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM, DeFrances C, Crane E, Cai R, and Naeger S. 2018. ‘Identification of Substance-involved Emergency Department Visits Using Data From the National Hospital Care Survey’, Natl Health Stat Report: 1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai R, Crane E, Poneleit K, and Paulozzi L. 2010. ‘Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs in the United States, 2004–2008’, J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother, 24: 293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coben JH, Davis SM, Furbee PM, Sikora RD, Tillotson RD, and Bossarte RM. 2010. ‘Hospitalizations for poisoning by prescription opioids, sedatives, and tranquilizers’, Am J Prev Med, 38: 517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Swendsen J, Husky MM, He JP, and Merikangas KR. 2016. ‘Association of Lifetime Mental Disorders and Subsequent Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement’, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 55: 280–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Tejada-Vera B, and Warmer M. 2017. ‘Drug Overdose Deaths Among Adolescents Aged 15–19 in the United States: 1999–2015’, NCHS Data Brief: 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AI, Dowell D, Lovegrove MC, McAninch JK, Goring SK, Rose KO, Weidle NJ, and Budnitz DS. 2019. ‘U.S. Emergency Department Visits Resulting From Nonmedical Use of Pharmaceuticals, 2016’, Am J Prev Med, 56: 639–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Mellor S, Olfson M, Lidon-Moyano C, and Schoenbaum M. 2020. ‘Mortality Following Nonfatal Opioid and Sedative/Hypnotic Drug Overdose’, Am J Prev Med, 59: 59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughwout SP, Harford TC, Castle IJ, and Grant BF. 2016. ‘Treatment Utilization Among Adolescent Substance Users: Findings from the 2002 to 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health’, Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 40: 1717–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2020. ‘Overview of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS)’, AccessedFebruary 27, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2019. ‘INTRODUCTION TO THE HCUP NATIONWIDE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT SAMPLE (NEDS) 2016’, AccessedOctober 30, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/neds/NEDS_Introduction_2016.jsp.

- Houchens R, Ross D, and Elixhauser A. 2015. “Final Report on Calculating National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Variances for Data Years 2012 and Later.” In HCUP Methods Series Report # 2015–09, edited by U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Ruan WJ, Saha TD, Smith SM, Goldstein RB, and Grant BF. 2006. ‘Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of nonmedical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions’, J Clin Psychiatry, 67: 1062–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Natale JE, Kissee JL, Dayal P, Rosenthal JL, and Marcin JP. 2017. ‘The Association Between Insurance and Transfer of Noninjured Children From Emergency Departments’, Ann Emerg Med, 69: 108–16 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Mack KA, and Paulozzi LJ. 2013. ‘Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010’, JAMA, 309: 657–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, and McAninch JK. 2015. ‘Emergency Department Visits and Overdose Deaths From Combined Use of Opioids and Benzodiazepines’, Am J Prev Med, 49: 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Control Centers for Disease, and Prevention. 2014. ‘Alcohol involvement in opioid pain reliever and benzodiazepine drug abuse-related emergency department visits and drug-related deaths - United States, 2010’, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 63: 881–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Alexander GC, Rutkow L, and Mojtabai R. 2017. ‘Emergency department visits involving benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists’, Am J Emerg Med, 35: 1414–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SM, Gryczynski J, Mitchell SG, Kirk A, O’Grady KE, and Schwartz RP. 2014. ‘Validity of brief screening instrument for adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and drug use’, Pediatrics, 133: 819–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust DT, Lin LA, and Blow FC. 2019. ‘Benzodiazepine Use and Misuse Among Adults in the United States’, Psychiatr Serv, 70: 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Veliz P, Wilens TE, West BT, Schepis TS, Ford JA, Pomykacz C, and Boyd CJ. 2019. ‘Sources of Nonmedical Prescription Drug Misuse Among US High School Seniors: Differences in Motives and Substance Use Behaviors’, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 58: 681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, and West BT. 2014. ‘Medical and nonmedical use of prescription benzodiazepine anxiolytics among U.S. high school seniors’, Addict Behav, 39: 959–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Morales M, Cranford JA, and Boyd CJ. 2007. ‘Does early onset of non-medical use of prescription drugs predict subsequent prescription drug abuse and dependence? Results from a national study’, Addiction, 102: 1920–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Wilens TE, Boyd CJ, Chua KP, Voepel-Lewis T, and Schepis TS. 2019. ‘Age-specific risk of substance use disorders associated with controlled medication use and misuse subtypes in the United States’, Addict Behav, 90: 285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Camargo CA Jr., Arias SA, Sullivan AF, Allen MH, Goldstein AB, Manton AP, Espinola JA, Jones R, Hasegawa K, Boudreaux ED, and Ed-Safe Investigators. 2017. ‘Suicide Prevention in an Emergency Department Population: The ED-SAFE Study’, JAMA Psychiatry, 74: 563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Swedler DI, Lawrence BA, Ali B, Rockett IRH, Carlson NN, and Leonardo J. 2020. ‘Incidence and Lethality of Suicidal Overdoses by Drug Class’, JAMA Netw Open, 3: e200607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro RN, Geller AI, Weidle NJ, Lind JN, Lovegrove MC, Rose KO, Goring SK, McAninch JK, Dowell D, and Budnitz DS. 2020. ‘Emergency Department Visits Attributed to Adverse Events Involving Benzodiazepines, 2016–2017’, Am J Prev Med, 58: 526–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. ‘Overdose Death Rates’, AccessedSeptember 10, 2020. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2019. ‘Screening Tools and Prevention’, AccessedDecember 9, 2020. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/screening-tools-resources/chart-screening-tools.

- Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, Arora M, Azzopardi P, Baldwin W, Bonell C, Kakuma R, Kennedy E, Mahon J, McGovern T, Mokdad AH, Patel V, Petroni S, Reavley N, Taiwo K, Waldfogel J, Wickremarathne D, Barroso C, Bhutta Z, Fatusi AO, Mattoo A, Diers J, Fang J, Ferguson J, Ssewamala F, and Viner RM. 2016. ‘Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing’, Lancet, 387: 2423–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, and Hockenberry JM. 2014. ‘Variation among states in prescribing of opioid pain relievers and benzodiazepines--United States, 2012’, J Safety Res, 51: 125–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, Ezeh AC, and Patton GC. 2012. ‘Adolescence: a foundation for future health’, Lancet, 379: 1630–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME,. 2018. “Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–55.” In. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller HA, Ackerman JP, Smith GA, Kistamgari S, Funk AR, McDermott MR, and Casavant MJ. 2020. ‘Suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among 10–25 year olds from 2000 to 2018: substances used, temporal changes and demographics’, Clin Toxicol (Phila), 58: 676–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019. “Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.” In. Rockville, MD:: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014. “The DAWN Report: Benzodiazepines in Combination with Opioid Pain Relievers or Alcohol: Greater Risk of More Serious ED Visit Outcomes.” In. Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toblin RL, Paulozzi LJ, Logan JE, Hall AJ, and Kaplan JA. 2010. ‘Mental illness and psychotropic drug use among prescription drug overdose deaths: a medical examiner chart review’, J Clin Psychiatry, 71: 491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2016. “FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning.” In. Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020. ‘FDA requiring Boxed Warning updated to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug class’. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class.

- Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hoots BE, Scholl L, Pickens C, Roehler DR, Board A, Mustaquim D, th Smith H, Snodgrass S, and Liu S. 2020. ‘Nonfatal Drug Overdoses Treated in Emergency Departments - United States, 2016–2017’, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 69: 371–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner M, Trinidad JP, Bastian BA, Minino AM, and Hedegaard H. 2016. ‘Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths: United States, 2010–2014’, Natl Vital Stat Rep, 65: 1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Zhao W, Xiang H, and Smith GA. 2012. ‘ED visits for drug-related poisoning in the United States, 2007’, Am J Emerg Med, 30: 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang VS, Olfson M, and King M. 2019. ‘Opioid and Benzodiazepine Coprescribing in the United States Before and After US Food and Drug Administration Boxed Warning’, JAMA Psychiatry, 76: 1208–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.