Abstract

Background:

To commemorate the 25th anniversary of International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in the pursuit of Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights views of duty bearers (men) who are mostly not involved in antenatal care in a patriarchal society like India needs to be explored.

Design:

It is a mixed method study (Triangulation).

Setting and Population:

It was conducted in a rural field practice area of a private medical college in South India covering a population of 19,200.

Objectives:

1) To determine the involvement of husband in maternal and child care. 2) To find out the perceptions of the husbands of antenatal pregnant women in maternal and child health (MCH) care.

Methods:

(Quan) A semi-structured questionnaire to find out the areas where husband is involved maximum during antenatal care (Qual). In-depth interviews was conducted to find out the factors associated with their involvement.

Results:

About 72.5% came for antenatal visits while it decreased to 27.5% during labor and further decreased to 20.3% during immunization. The reasons for decreased participation were (1) Professional Commitments, (2) Views of a Patriarchal society like India, (3) Financial Difficulties, and (4) Health Facility Related Challenges.

Conclusion:

There is a need to educate the husband regarding the importance of husband's involvement during delivery and immunization. Programs should also include men as the stakeholders for accountability and better MCH care for women.

Keywords: Husband, involvement, maternal and child health care

Introduction

The maternal and child health (MCH) has been one of the most important components of a nation's health.[1] Maternal healthcare service comprises services provided for women during pregnancy, delivery, and postnatal.[2] For decades, maternal mortality and infant mortality rates has been used as a measure of a country's progress toward global health goals. It marks the 25th anniversary of the Cairo of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) which is a platform for all interested in the pursuit of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights which includes duty bearers (men) who are mostly not involved in antenatal care in a patriarchal society like India.[3] The MCH program in India has undergone drastic changes over the years, currently the RMNCH + A is built on the concept of continuum of care.[1] While WHO has recommended the support and active involvement of male for better maternal and child health outcomes, this recommendation is yet to find its place in RMNCH+A.[4]

In a patriarchal society like India, pregnancy, child birth is always considered as exclusive duties belonging to the mother/female gender. Many studies in recent times have demonstrated that involving males in antenatal care has resulted in better outcomes for mother and child.[5] In the last two decades, many national plans in India have re-emphasized the importance of male involvement, yet without any clear policy directives and a monitoring system to measure the achievements of the program in enhancing male participation in women-related health programs.[6] Tamil Nadu is making rapid progress toward reducing the maternal and infant mortality in the state.[7] Most of this decline in mortality can be attributed to increase in accessibility to care. Involvement of male in maternal care can prove as one of the efficient ways to accelerate this progress and consolidate the gains made in previous years. So this study was undertaken to understand about the involvement of males in antenatal and child care in a rural area.

Objectives

-

1)

To determine the involvement of husband in maternal and child care.

-

2)

To find out the perceptions of the husbands of antenatal pregnant women in MCH care.

Methodology

Study design

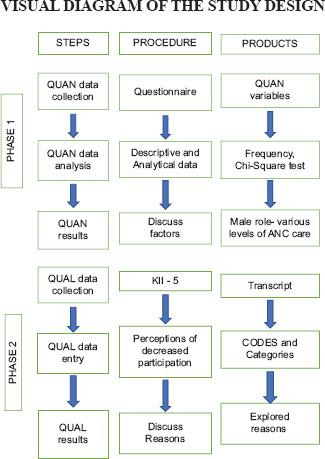

PHASE 1 –It is a triangulation type of mixed method study[8] where initially a questionnaire was used to find out the involvement of men in the MCH care.

PHASE 2 – Following which five Key informant interviews[9] was conducted to explore the reasons for poor participation of men during labor and immunization.

VISUAL DIAGRAM OF THE STUDY DESIGN

Study duration

It was conducted for duration of 2 months from January to February 2019.

Study setting

The study was conducted in the rural field practice area of a private medical college. The field practice area includes one rural health and training center covering a population of 19,200.

Phase 1: Quantitative

Non-probability purposive sampling was carried out. All women having last child below 1 year attending the immunization clinics on Wednesdays in rural health center for 2 months were taken as study subjects which came to 69.

Inclusion criteria: Study participants of any gravidas who gave consent and having the last child below 1 year.

Exclusion criteria: Mother having living children above 1 year of age and who did not give consent.

Data collection procedure: The data collection was done using pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire by direct interview to the study respondents. The questions were asked in the local language (Tamil) and written informed consent was obtained prior to the interview. The questionnaire included the sociodemographic profile and the relevant questions on husband involvement. The data entry and analysis were done using SPSS software V 21. Descriptive statistics were used for summary of the findings. Chi-square test was used to find out the association between all the variables with husband involvement.

PHASE 2: Qualitative: Five KII were taken with the husbands of the women who attended the immunization clinic by contacting them with an appropriate time and place for each. They were purposively selected assuming they will shed some light into the perceptions of decreased participation. A trained interviewer interviewed the key informants using semi-structured guidelines which had open-ended questions on the decreased participation of husbands during Labor and immunization phase. The interviews were audio recorded and manual content analysis was done. Inductive and Deductive codes from the transcripts were merged to form categories.

Results

(Quan) Majority belonged to Hindu religion (88.4%) and BC caste (55.1%). Almost 60% of fathers have completed only secondary education, and 50% were belonging to the occupation category of clerical/shop owner/farmer. About 50% belonged to class III socioeconomic status. About 70% have registered their pregnancy in government hospital. Around 82.6% of the delivery took place in mother's place [Table 1].

Table 1.

Preliminary information of study participants (n=69)

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| No of children | ||

| 1 | 26 | 37.7 |

| 2 and above | 43 | 62.3 |

| Registration of Pregnancy | ||

| Government | 48 | 69.6 |

| Private | 21 | 30.4 |

| Planning of Pregnancy | ||

| Planned | 55 | 79.7 |

| Unplanned | 14 | 20.3 |

| Place of Delivery | ||

| Husbands Place | 57 | 17.4 |

| Mothers place | 12 | 82.6 |

The percentage of husbands accompanying during antenatal visit were 72.5% while it decreased to 27.5% during labor and further decreased to 20.3% during immunization [Chart 1]. While coming to expenses husband contribution was comparatively good for traveling (64%) and almost half have contributed for nutrition (42%) and medicine (48%). But the expense for delivery is paid by the mother's side in 74% of the cases. Mean number of antenatal visits by the mothers were 4.8 and the mean number of visits accompanied by husband was 2.4 [Table 2]. The factors like religion, husband's education and occupation, socioeconomic status, planning of pregnancy, registration of pregnancy and place of delivery were checked for association with spousal involvement during antenatal care, labor, and immunization but none were statistically significant.

Chart 1.

Husbands Involvement in Maternal and Child Health care (N = 69)

Table 2.

Monetary involvement of Husband in maternal and Child health care (n=69)

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Expenses - travelling | ||

| Husband | 44 | 63.8 |

| Mothers House | 25 | 36.2 |

| Expenses - Nutrition | ||

| Husband | 29 | 42 |

| Mothers House | 40 | 58 |

| Expenses - Medicine | ||

| Husband | 33 | 47.8 |

| Mothers House | 36 | 52.2 |

| Expenses -Delivery | ||

| Husband | 18 | 26 |

| Mothers House | 51 | 74 |

|

| ||

| Visits of husband before and after pregnancy | Mean (S.D.) | |

|

| ||

| Number of visits accompanied by husband pre-pregnancy | 2.4 (1.5) | |

| Number of visits by husband post pregnancy | 5 (1.1) | |

(Qual): The mean age of the participants was 32 ± 1.48 (years ± SD). The categories that emerged were professional commitments, patriarchal society, financial difficulties, and health facility related challenges [Table 3].

Table 3.

Perceptions of Husbands Poor Participation during Labour and Immunization

| Codes | Categories | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Holidays/Paternity Leave | Professional Commitments | Reasons of poor participation During Labour and Immunization |

| Non - Cooperative colleagues/co-workers for duty exchange | ||

| Lack of Time Management skills | ||

| Traditional Birth Preparedness - Mothers place | Patriarchal Society | |

| Lack of cooperation between in laws. | ||

| Misogynistic Views | ||

| Lack of Belief in Immunization. | ||

| Lack of preparedness | Financial Difficulties | |

| Unplanned Pregnancy | ||

| Early Marriage | ||

| Long Waiting Hours | Health Facility - Related Challenges | |

| Crowded Out patient departments | ||

| Vaccines - Arriving late | ||

| Results (Qual): | ||

| The mean age of the participants was 32±1.48 (years±SD) | ||

| The categories that emerged were Professional Commitments, Patriarchal Society, Financial Difficulties and Health Facility related challenges | ||

| Category 1: One participant said, “I am the sole bread winner in the family. I have to run whether it is raining or a sunny day” | ||

| Category 2: “It is the duty of the mother’s family”. About three out of five men had misogynistic views, “Women are created for the purpose of giving birth. It is no big deal. It is the law of nature” | ||

| Category 4: “Meeting the doctor for vaccination takes lot of time as the PHC has a long queue” | ||

Category 1: One participant said, “I am the sole bread winner in the family. I have to run whether it is raining or a sunny day.”

Category 2: ”It is the duty of the mother's family.” About three out of five men had misogynistic views, “Women are created for the purpose of giving birth. It is no big deal. It is the law of nature.”

Category 4: “Meeting the doctor for vaccination takes lot of time as the PHC has a long queue.”

Discussion

Sociodemographic details

Majority belonged to Hindu religion (88.4%) and 60% of fathers have completed only secondary education, 50% were belonging to the occupation category of clerical/shop owner/farmer. About 70% have registered their pregnancy in government hospital. About 82.6% of the delivery took place in mother's place. The expense for delivery is paid by the mother's side in 74% of the cases. These characteristics are specific to the context of rural population having farming as their main livelihood and choosing government setup for the maternal benefits under RMNCH + A programme in India.

The percentage of husbands accompanying during antenatal visit were 72.5% while it decreased to 27.5% during labor and further decreased to 20.3% during immunization. Mean number of antenatal visits by the mothers were 4.8 and the mean number of visits accompanied by husband was 2.4. There has been no study in India to compare directly the male involvement in various stages, however Narang et al.[10] a study done in Delhi demonstrated 61% of men accompanied the women during the antenatal care which is similar to present study. However, a study conducted by Bhatta et al. in Nepal and Craymah et al. in Ghana reported 39.3% and 35% of men participated in the antenatal visits. These values are very low compared to our study as they are very low-income countries and the sample size is relatively small in our study. Mohammed S, et al.[11] from Kenya in 2020 did a age specific comparison to this facet where 62.7% of the women who were in the age group of 20–29 years said that the men were present throughout their antenatal visits, women <20 years and more than 40 years said that they went to the hospital alone on all days during their antenatal period. Another study by Fatila FO, et al.[12] from Kenya in 2020 reported that men involved in antenatal care was 54.5%, postnatal care 87.7%, and new born care 51%. This study did not explicitly mention the definitions of antenatal care, postnatal care, and newborn care which may attribute to the high percentage of postnatal care and new born care.

Male participation during labor and immunization is 47% and 44%, 10 and 20% in Bhatta et al. and Craymah et al.[2,13] Our study reported a 27.5% attendance during labor which is very low compared to the other studies as we follow the traditional practices of conducting delivery at mother place. Fathers hardly attended the immunization rounds of their children in our study which agrees with lot of studies.[2,6,13]

In this study factors like religion, husband's education and occupation, socioeconomic status, planning of pregnancy, registration of pregnancy and place of delivery were not significantly associated with spousal involvement during antenatal care, labor, and immunization. However, other studies have found certain factors to be significantly associated with male involvement age, religion, education, employment, income, number of children, planning of pregnancy.[2,13,14] This may be because of the small sample size.

To explore the reasons for poor participation of men during immunization and labor, five Key informant interviews were conducted among the men who were vocal and willing to participate. The reasons were (1) Professional Commitments, (2) Views of a Patriarchal society like India, (3) Financial Difficulties, and (4) Health Facility Related Challenges. There is no qualitative study done in South India exploring these factors. Recognizing the areas of poor participation by men and exploring the thematic reasons behind them was a novel approach in this study.

Under the category of patriarchal society, one of the participant quoted, “It is the sole duty of the female, I don’t understand how it is relevant to us? ” (Men). This clearly states that a preconceived notion of assigned duties to the male and female gender exists among the society. This society norm is very flawed and behaviour change among the men is required for enabling better antenatal, postnatal, and child care. Another flaw was that there is no proper paternity leave in private organizations in India. These reasons should be addressed as a society and programs should be built around it. A qualitative study done in Malawi by Mkandawire et al.[15] said that sociocultural beliefs, stigmatization were some of the reasons for poor participation.

The strength of this study is it is a mixed method study design,[8] which helps us to understand the problem as a whole. Knowledge of the husband regarding antenatal care and various other postnatal variables like breastfeeding, helping in daily household chores of the child were not included. However, we should keep in mind the small sample size as it is limited to one particular area (rural) and only one teaching hospital.

Summary and Conclusion

The husband involvement in our study is better during antenatal period but they have steadily decreased during delivery and immunization.

The reasons for the decreased participation were (1) Professional Commitments, (2) Views of a Patriarchal society like India, (3) Financial Difficulties, and (4) Health Facility Related Challenges.

Misogynistic views of men and society norms considering women mainly for domestic chores and child bearing and rearing requires serious behaviour change.

There is a urgent need to educate the husband regarding the importance of husband's involvement during delivery and immunization. Programs should emphasize on these factors for men to participate more in the MCH care. Further studies can be done to strengthen the participation of men in the continuum of care in India.

Ethical clearance

Clearance from the institutional research committee was obtained. Later the Institutional Ethics clearance was also obtained with (IEC No of 003) on 30.1.2020.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Park K. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 23rd ed. Jabalpur: M/S Banarsidas Bhanot; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craymah J, Oppong R, Tuoyire D. Male involvement in maternal health care at Anomabo, Central Region, Ghana. Int J Reprod Med 2017. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/2929013. 2929013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis J, Vyankandondera J, Luchters S, Simon D, Holmes W. Male involvement in reproductive, maternal and child health: A qualitative study of policymaker and practitioner perspectives in the pacific. Reprod Health. 2016;13:81. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0184-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO recommendations on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health. [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2015. [[cited 5 September 2019]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/health-promotion-interventions/en/ [PubMed]

- 5.Comrie-Thomson L, Tokhi M, Ampt F, Portela A, Chersich M, Khanna R, et al. Challenging gender inequity through male involvement in maternal and newborn health: Critical assessment of an emerging evidence base. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(sup 2):177–89. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1053412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chattopadhyay A. Men in maternal care: Evidence from India. J Biosoc Sci. 2012;44:129–53. doi: 10.1017/S0021932011000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHFS State Fact sheet Tamil Nadu. [Internet]. NFHS 2015-16. [[cited 28 November 2020]]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/pdf/NFHS4/TN_FactSheet.pdf .

- 8.Bergman MM, editor. Advances in Mixed Methods Research: Theories and Applications. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UCLA center for Health policy research. [Internet] [[cited 28 November 2020]]. Available from: https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/programs/health-data/trainings/Documents/tw_cba23.pdf .

- 10.Narang H, Singhal S. Men as partners in maternal health: An analysis of male awareness and attitude. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2:388–92. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohammed S, Yakubu I, Awal I. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Women's Perspectives on Male Involvement in Antenatal Care, Labour, and Childbirth. J Pregnancy. 2020;Jan 25;2020:6421617. doi: 10.1155/2020/6421617 doi: 10.1155/2020/6421617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fatila FO, Adebayo MA. Male partners’ involvement in pregnancy related care among married men in Ibadan, Nigeria. BMC Reprod Health. 2020;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0850-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatta DN. Involvement of males in antenatal care, birth preparedness, exclusive breast feeding and immunizations for children in Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fekede Asefa, Ayele Geleto, Yadeta Dessie, Male Partners Involvement in Maternal ANC Care: The View of Women Attending ANC in Hararipublic Health Institutions, Eastern Ethiopia. Science Journal of Public Health. 2014;2:182–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mkandawire E, Hendriks SL. A qualitative analysis of men's involvement in maternal and child health as a policy intervention in rural Central Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:37. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1669-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]