Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the different styles of parenting in the State of Qatar, a country that is considered a cosmopolitan hub with rapid development.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted at Sidra Medicine, the only tertiary pediatric hospital in Qatar. Parents of children 3–14 years old were offered a questionnaire.

Results:

A total of 114 questionnaires were completed (response rate = 95%). Approximately 65% of parents were between 30 and 39 years of age. Almost 90% of parents state that they are confident of their parenting ability. More than 90% of the participating parents stated that they are responsive to their child's feeling and needs, give comfort and understanding when their child is upset, praise their child when well-behaved, give reasons why rules should be followed, help children understand the impact of their behavior, explain consequences of bad behavior, take into account their child's desire before asking him/her to do something, encourage their child to freely express him/herself when disagreeing with his/her parents, and show respect to their child's opinion. However, 60% of parents sometimes scold, yell, and criticize their child when he/she misbehaves but less than 50% of them use threats as a consequence with little or no justification. Furthermore, two-thirds of parents give consequences by putting their child off somewhere with little or no explanation. Moreover, one in four participants gives in to their child when he/she causes a commotion about something, threatens their child with consequences more often than actually giving them, and states consequences to their child and do not actually do them.

Conclusion:

Residents in Qatar have a mixed type of parental style (authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive). This study will guide us to raise the awareness about the types of parenting style in Qatar, in order to provide professional parenting counseling taking into consideration the cultural background.

Keywords: Children, parenting, pediatric, Qatar, style

Introduction

During the crucial age of children's growth and development, the parents are the children's first tutors. Features of parental control, including supervising, discipline, autonomy conceding, in addition to emotional constituents of parent behaviors, including acceptance, warmth, and receptiveness, constantly rise as predictors of children's adjustment.[1] The degree to which parents exhibit behaviors in either control, emotion, or mixed grade their parenting style as permissive, authoritarian, or authoritative.[2] Caregivers who mainly exhibit control behaviors and less care are characterized as authoritarian, parents who exhibit both control and affection are described as authoritative or democratic, and parents who use behavioral approaches determined on affection and less parental control are characterized as permissive.[3]

Culture comprises a solid feature in organizing parental practices since it can influence parental belief. Dwairy et al.[4] conducted in the Middle East in eight different Arab societies, and showed different styles of parenting depending on the society. A study in the United States showed that parenting styles differ considerably by communities as measured by their ethnicity or race. For instance, Latinos and Asian–American communities were more authoritarian and less authoritative compared to Caucasians.[5]

Up to our knowledge, there are no studies in the state of Qatar that investigated parental styles and the effect of duration of residency on those styles. The population of the State of Qatar is 2,839,386, and Qataris constitute 12% of them. The remaining 88% comprise migrants from over a hundred different nationalities.[6]

We aim to explore types of parenting styles that are available in the native Qatari and non-Qatari population having the fact that they are sharing the same environment but having different background.

We have used the modified version of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ), an instrument that has been used worldwide for the measurement of several parenting aspects as well as broader parenting styles. This study will guide us to raise the awareness about the types of parenting styles in Qatar, in order to provide professional parenting counseling to the future parents to meet their needs.

Materials and Methods

Study Type

Here, a cross-sectional prospective study has been used. We have used a modified version of the PSDQ comprising 34 items (including demographics), initially described by Baumrind.[7,8,9]

This questionnaire was offered in two languages, English and Arabic. The Arabic version was translated from English by professional translation services. The items of the questionnaire were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). On each item, participants informed the frequency with which he or she uses the specific behavior described, and all items were gathered into three styles of parenting.

Study Location

The study was conducted in the pediatric inpatient and outpatient departments of Sidra Medicine, the only tertiary institution in the State of Qatar at the time of the study.

Sample Size

We have calculated the sample size based on the average mean of parenting styles {permissive (>26.78 + 1 SE.11), authoritarian (>27.09 + 1 SE.13), and authoritative (>37.11 + 1 SE.13)} in eight Arab societies.[4]

Looking at mean range, average will be as follows: permissive 27.55, authoritarian 28.37, and authoritative 38.2475. Standard deviation range between 8 and 10 and with the 95% confidence level and the desired margin of error (E) is 5%, the minimum number of participants required to ensure that the margin of error in the confidence interval for the population mean does not exceed E is n = 70 subjects. However, to account for many subgroup analyses and several secondary outcome measures, the plan is to enroll a total of 100 participants in this current research study.

Study Population

Parents of children 3–14 years of age were approached while visiting the outpatient department for well visits or sick visits, as well as parents of hospitalized children.

Parents who are younger than 18 years of age, step-parents, and divorced mothers/fathers who are not living with their kids were excluded. We also excluded parents of children with the following conditions: development delay, learning disability, hearing/visually impaired, musculoskeletal disability, and respiratory compromise. The reason for exclusion is due to the extra challenge that parents might face when raising them.

A verbal consent form was offered before giving out the questionnaire, and participants were informed of why the information was being collected and how it would be used. Participants were notified that their participation was voluntary and we have confirmed that their answers were confidential and anonymous. Parents did not receive any monetary or nonmonetary compensation for participating in the study. In addition, we have informed caregivers that the project received approval from Sidra Research Office and Sidra Institutional Board Review Committee (#IRB 2019-0002).

Study Period

April 1, 2019 till March 30, 2020.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis, and a two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Qualitative and quantitative data measurements were exhibited as percentages. Descriptive statistics explained the demographics and other characteristics of parents and children. Associations between two or more categorical variables were appraised using the Chi-square test. For small cell frequencies, a Chi-square test with continuity correction factor or Fisher's exact test was used. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the associations of various potential predictors and covariates. Missing data were not accounted for in the analysis. Hierarchical clustering was used to plot and identify the three types of parenting.

Results

A total of 114 questionnaires were completed (response rate = 95%). Approximately 65% of parents were between 30 and 39 years of age. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant | ||

| Mother | 69 | 60.5 |

| Father | 41 | 36 |

| Others | 4 | 3.5 |

| Age | ||

| <29 | 16 | 14 |

| >30 | 98 | 86 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 4 | 3.5 |

| Married | 103 | 91 |

| Divorced or widowed | 6 | 5.5 |

| Parent’s rank among siblings | ||

| Oldest or only child | 33 | 29 |

| Middle or youngest child | 79 | 71 |

| For non-Qatari, years of residency in Qatar | ||

| Less than 10 years | 50 | 44 |

| More than 10 years | 26 | 23 |

| Academic level | ||

| High school or less | 28 | 24.5 |

| Bachelor or higher | 86 | 75.5 |

| Employment | ||

| A student or unemployed | 46 | 40 |

| Working and studying | 68 | 60 |

Approximately 90% of parents state that they are confident of their parenting ability. More than 90% of the participating parents stated that they are responsive to their child's feeling and needs, give comfort and understanding when their child is upset, praise their child when well-behaved, give reasons why rules should be followed, help children understand the impact of their behavior, explain consequences of bad behavior, take into account their child's desire before asking him/her to do something, encourage their child to freely express him/herself when disagreeing with his/her parents, and show respect to their child's opinion.

However, 60% of parents sometimes scold, yell, and criticize their child when he/she misbehaves, but less than 50% of them use threats as a consequence with little or no justification. Furthermore, two-thirds of parents give consequences by putting their child off somewhere with little or no explanation.

Furthermore, one in four participants give in to their child when he/she causes a commotion about something, threaten their child with consequences more often than actually giving them, and state consequences to their child and do not actually do them.

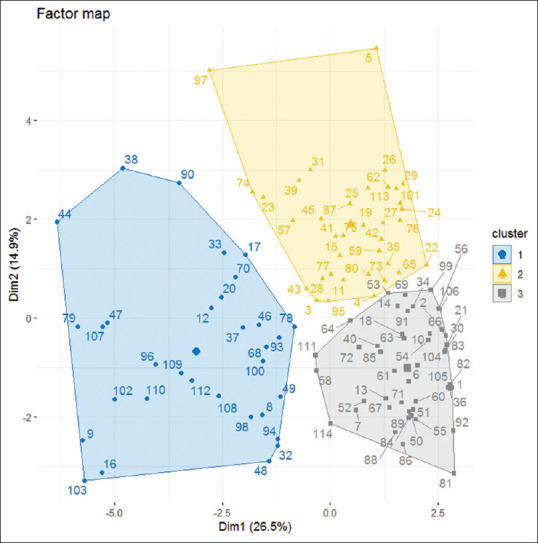

Ascending hierarchical classification [Figure 1] of the participants was carried out.

Figure 1.

Ascending hierarchical classification of the individuals. The classification made on individuals reveals three clusters (groups)

Group 1 was formed by 11 Qatari, 16 Arab non-Qatari, and 5 from other nationalities. More precisely, it is formed by 1 Bangladeshi, 1 Egyptian, 2 Indians, 4 Jordanians, 1 Kuwaiti, 3 Pakistanis, 1 Palestinian, 2 Sudanese, 3 Syrians, 1 Yemeni, 1 American, and 11 Qatari nationals. This group scored toward the authoritarian parenting style. Almost 60% of participants were females, 80% were older than 30-year old, and around 80% were married. Almost 70% were either the youngest among their siblings or were the middle child. 70% had Bachelor's degrees or higher, and 60% were employed.

Group 2 comprised of 15 Qatari, 15 Arab non-Qatari, and 6 from other nationalities and used a mixture of the 3 parenting styles. Approximately, 60% of participants were females, and 80% were above 30-year old. All parents were married. Among the participants, almost 80% were ranked as the youngest or middle child among their siblings. Around 70% had Bachelor's degrees or higher, and more than 50% were unemployed.

Group 3 used an authoritative parenting style and included 12 Qatari nationals, 20 Arab non-Qatari, and 14 from other nationalities. 60% of participants were females, 85% were 30 years older, and 85% were married. 60% were middle children in their families or were the youngest, 80% had Bachelor's degrees or higher, and around 70% were employed.

Associations among sociodemographic factors, such as age, nationality, rank in family, years of residence in Qatar, marital status, education, and employment status, and parenting styles were not statistically significant (P = 0363, 0.364, 0.220, 0.788, 0.821, 0.80, and 0.079, respectively).

Discussion

The current investigation is the first study in Qatar to examine parenting styles among citizens and residents. It measured parental insights about the general and specific aspects of parenting. Overall our participating population showed that they have different parenting styles regardless of age, nationality, or any socioeconomic factors. In other words, it seems that much of the change of the items is common and that parenting styles among inhabitants in the state of Qatar do not categorize exclusively in the three known parenting styles. These findings concur with and Kagitcibasi's[10] and Chao's[11] disparagement of Baumrind's typology and back their theory that parental control and warmth may be harmonious in some combined societies.

Parenting is more than a set of explicit practices that can have an effect on the ways that children develop.[12] Caregivers play a crucial role in caring for their children and making choices for their beloved ones (Sobo, 2004). Their views and understanding of care may differ from those perceived by clinicians. Delineating parental perceptions is vital to evolving programs and solutions and is essential to the founding of patient-centered care.[13,14]

Despite Baumrind's ideology, being applied in China, Turkey, Brazil, China, Scandinavia, and the Mediterranean European countries,[2,15,16,17] the basic parenting styles do not always plot onto local parenting systems.

Kim and Rohner[18] explored the connection between Baumrind's parenting styles (authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and rejecting/neglecting) and the academic attainment of 245 Korean American adolescents (Grades 6–12). The study concluded that approximately 75% of the sample population did not fit into any of the standard categories in parenting, creating doubt regarding their usefulness for ethnic research.

Chao[11] and Darling[12] investigated Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. The study concluded that authoritative and authoritarian are somewhat ethnocentric and does not have exact correspondence in traditional Chinese child-rearing.

In terms of some insight regarding parenting in the Arab world. In Saudi Arabia, boys are more prone to corporal punishment as compared to girls, despite the notion or perception that that females are being treated more strictly[19]. Palestinian male adolescents in Israel perceive their parental style as more authoritarian than females do.[20] Palestinian males in the Gaza Strip also sensed parental treatment as more negatively (more hostile and stricter discipline) compared to females.[21]

The literature has shown that parental economic status, education, and urbanization affect the parenting styles and practices. This link between socioeconomic classes and a strict style of parenting is global.[4] However, that was not the case in our study.

Qatar society is considered unique. Private schools constitute a large sector and students from all nationalities, including Qatari nationals, interact under one roof and during extracurricular activities. The majorities of teachers in private school are non-Qatari citizens (Americans, Europeans, Egyptians, Lebanonians, Indians, etc.). English language is used very frequently in enhancing communications in schools, malls, gyms, restaurants, etc., Moreover, the government of Qatar grants numerous financial scholarships to their citizens to study in the west, especially Europe, Canada, and the United States. The majority of them (if not all) return to their home country after completion of their abroad education. Moreover, Qatari nationals travel very frequently to the west and east and they have knowledge of the global culture. All of the above contributed to the inability to delineate a specific parenting style in this wealthy, rapidly developing cosmopolitan country.

The results of this study emphasize the need for developing efficient parental education programs to augment their knowledge of child development in Qatar. Given the country's rapid economic growth and great resources, those programs are feasible and can be accessed easily.

Parental attitude toward mixed parenting could be elucidated because parents gave the answer they perceived would be the most socially desirable, instead of providing the response they truly wanted to give. However, this desire was minimized by emphasizing that their participation was voluntary and that their answers were anonymous and confidential.

This study has important strengths, specifically both the quantitative and qualitative observations. Our study will assist in creating programs to cater to proper parenting in our rapidly developing nation.

This study also has limitations. There might be a possibility that there are certain aspects related to parental parenting not evaluated in this study. Moreover, this study collected perceptions from parents, but delineating the teenagers' perceptions would be invaluable.

Conclusion

Residents in Qatar have a mixed type of parental style (authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive). This study will guide us to raise the awareness about the types of parenting styles in Qatar, in order to provide professional parenting counseling taking into consideration the cultural background.

Ethical approval

Sidra Medicine IRB approved this study (#IRB 2019-0003).

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Key Messages

Population in Qatar have different parenting styles regardless of age, nationality, or any socioeconomic factors.

Parenting styles among inhabitants in the state of Qatar do not categorize exclusively in the three known parenting styles.

Approximately 90% of parents state that they are confident of their parenting ability.

Financial support and sponsorship

The article processing fees are covered by Qatar National Library.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Many Thanks to Dr. Mohammed Elanbari for the data analysis.

References

- 1.Tedgård E, Tedgård U, Råstam M, Johansson BA. Parenting stress and its correlates in an infant mental health unit: A cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74:30–9. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2019.1667428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira TD, Costa DS, Albuquerque MR, Malloy-Diniz LF, Miranda DM, de Paula JJ. Cross-cultural adaptation, validity, and reliability of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire-Short Version (PSDQ) for use in Brazil. Braz J Psychiatry. 2018;40:410–9. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muir K, Joinson A. An exploratory study into the negotiation of cyber-security within the family home. Front Psychol. 2020;11:424. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwairy M, Achoui M, Abouserie R, Farah A, Sakhleh AA, Fayad M, et al. Parenting styles in Arab societies: A first cross-regional research study. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2006;37:230–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pong SL, Johnston J, Chen V. Authoritarian parenting and Asian adolescent school performance: Insights from the US and Taiwan. Int J Behav Dev. 2010;34:62–72. doi: 10.1177/0165025409345073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qatar Population and Expat Nationalities. OnlineQatar. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.onlineqatar. com/visiting/tourist-information/qatar-population-and-expat-nationalities .

- 7.Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumrind D. Rearing competent children. In: Damon W, editor. Child Development Today and Tomorrow. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1989. pp. 349–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumrind D. Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In: Cowan PA, Hetherington M, editors. Family Transitions. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 111–63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kagitcibasi C. Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2005;36:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 1994;65:1111–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:487–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobo EJ, Seid M, Reyes Gelhard L. Parent-identified barriers to pediatric health care: A process-oriented model. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:148–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobo EJ. Good communication in pediatric cancer care: A culturally-informed research agenda. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21:150–4. doi: 10.1177/1043454204264408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Wei X, Ji L, Chen L, Deater-Deckard K. Reconsidering parenting in Chinese culture: Subtypes, stability, and change of maternal parenting style during early adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:1117–36. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0664-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Türkel YD, Tezer E. Parenting styles and learned resourcefulness of Turkish adolescents. Adolescence. 2008;43:143–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez I, García JF, Yubero S. Parenting styles and adolescents' self-esteem in Brazil. Psychol Rep. 2007;100:731–45. doi: 10.2466/pr0.100.3.731-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K, Rohner RP. Parental warmth, control, and involvement in schooling: Predicting academic achievement among Korean American adolescents. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2002;33:127–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Achoui M. Taa'dib al atfal fi al wasat al a'ai'li: Waqea' wa ittijahat [Children disciplining within the family context: Reality and attitudes] Al tofoolah A Arabiah. 2003;16:9–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwairy M. Parenting styles and mental health of Palestinian-Arab adolescents in Israel. Transcult Psychiatry. 2004;41:233–52. doi: 10.1177/1363461504043566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Punamäki RL, Qouta S, el Sarraj E. Models of traumatic experiences and children's psychological adjustment: The roles of perceived parenting and the children's own resources and activity. Child Dev. 1997;68:718–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]