Abstract

Fourteen verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from stool samples of 14 different asymptomatic human carriers were further characterized. A variety of serotypes was found, but none of the strains belonged to serogroup O157. Only one isolate carried most of the virulence genes that are associated with increased pathogenicity.

The importance of the verotoxin (VT)-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) group has increased since a food-borne infection caused by enterohemorrhagic E. coli was first described (17). Other serogroups, like O26, O111, and O103, have also been found in affected patients, in addition to the classic serovars O157:H7 and O157:H− (3, 5, 13). Apart from the ability to produce VT, these pathogroups may possess accessory virulence factors associated with the capacity to colonize the gut, such as intimin and a 90-kbp virulence-associated plasmid (2, 12). In patients, VTEC strains are associated with watery or bloody diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome (7, 9). Because of the lack of a national surveillance program, the incidence of these diseases and the isolation rate of VTEC in Switzerland are not known. Cattle are considered to be the main reservoir of VTEC (9, 22). Burnens et al. (4) described a Swiss prevalence of 21%. Therefore, the source of this food-borne infection was often found to be foods of bovine origin or other fecally cross-contaminated foods. Person-to-person transmission has been reported during outbreaks and may account for a significant number of sporadic cases (7, 16). An important question to address, however, is the role of asymptomatic human carriers in food-producing companies as a source of contamination. One study of Canadian dairy farm families (a group with a high level of environmental exposure) detected carriage of VTEC in about 6% of the individuals (23). The aim of this study was to isolate VTEC strains of stool samples from staff members of food-producing companies and to compare their serotype distribution and the presence of virulence attributes.

In an ongoing study of routine stool samples from staff members of meat-processing companies, 1,730 specimens from different persons in all parts of Switzerland were examined in October and November 1997 by using PCR for detection of VT-encoding genes and by culture methods for detection of other pathogens relevant to food hygiene. All samples were collected in urban areas, and each person was tested only once. The population consisted of adults without diarrhea aged between 20 and 60 years, a quarter being female.

For the VTEC assay, samples were directly plated on sheep blood agar, and after 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the colonies were washed off in normal saline. The plate eluate obtained was then evaluated by PCR with primers based on sequences targeting a region conserved between the genes for which are VT1 and VT2 complementary to nucleotides 439 to 462 and 943 to 962 of the sequence with EMBL/GenBank accession no. M19473 for the VT1-encoding gene (20) and to nucleotides 515 to 538 and 1016 to 1035 of the sequence with EMBL/GenBank accession no. X07865 for the VT2-encoding gene (8). The sequences of primers used and the cycling conditions have been described by Burnens et al. (4). Bacterial DNA was prepared by incubating 2 μl of washed-off cultures in 42 μl of double-distilled water for 10 min at 100°C. Amplifications were performed in a total volume of 50 μl containing 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 30 pmol of each primer, 5 μl of 10-fold-concentrated polymerase synthesis buffer, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA cycler. The amplified products were visualized by gel electrophoresis in 0.9% agarose agar stained with ethidium bromide. E. coli EDL933 was used in each run as a positive control, and E. coli U4-41 was used as a negative control. The eluate was plated again on MacConkey agar, and at least 18 single colonies each were tested by the same PCR protocol in 27 positive samples in order to obtain VTEC isolates. Only one VT-producing strain per sample was then subjected to further typing. The strains were biochemically confirmed as E. coli (acid production from mannitolol, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [ONPG] test, H2S and indole production, and proof of urease and lysine decarboxylase). Moreover, they were tested for sorbitol fermentation and β-d-glucuronidase activity on Fluorocult agar (Merck 4036) and for the hemolytic phenotype by using CaCl2-washed blood agar. Production of VT by each isolated strain was confirmed by cytotoxicity tests on Vero cells (11). The genotype of the VT B subunit and the presence of the E-hlyA, eae, and astA genes and the 60-MDa plasmid was determined by separate PCRs. The sequences of the primers used and the cycling conditions have been previously described (6, 18, 19, 24). Serotyping of somatic and flagellar antigens was performed at the Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark.

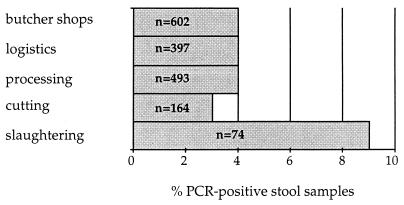

The PCR product of VT-encoding genes was detected in 79 (4.6%) (61 from males, 18 from females) of the 1,730 stool samples analyzed in this study. Comparatively, we found Salmonella spp. in 3 (0.17%), Campylobacter spp. in 7 (0.4%), Yersinia spp. in 10 (0.69%), and Listeria spp. in 13 (0.75%) samples. No geographic clustering of VT gene-positive samples was found, but if the distribution frequency of PCR-positive stool samples is compared to the workplaces of the employees, the following account can be found (Fig. 1). Slaughtering stands out with 9%. Working in a slaughterhouse, where individuals would presumably encounter VTEC bacteria more frequently and in higher numbers, may put them at higher risk for carriage or excretion of these organisms. It must be considered, however, that in this area a substantially smaller number of persons (n = 74) could be examined. Therefore, this observation must be backed up with further examinations.

FIG. 1.

Distribution frequency of PCR-positive stool samples compared to the workplaces of the employees (n = number of employees examined).

Fourteen VTEC strains isolated from stool samples of 14 different persons from all five work areas were further characterized. Serotyping yielded seven different O:H serotypes comprising seven O serogroups and seven H serogroups. Three strains were O nontypeable, and two were O rough; all strains were motile (Table 1). Compared to isolates found in patients (15), three strains (O76:H19, O113:H4, and O146:H28) isolated from asymptomatic human carriers had common serotypes, but the serotypes of these VTEC isolates are not those which have been convincingly and frequently associated with human disease. Further results of strain characterization are summarized in Table 1. Phenotypically, all 14 strains were both sorbitol and β-d-glucuronidase positive and also positive in the Vero cell cytotoxicity test. Subtyping of the VT genes of the isolated strains by using VT1- and VT2-specific primers showed that three strains possessed VT1 alone, nine strains possessed VT2 genes, and two strains possessed both VT1 and VT2. Since most patients developing the hemolytic-uremic syndrome are infected with strains that harbor the VT2 type (10, 14, 21), these findings in asymptomatic human carriers are astonishing. The eae gene, which is strongly correlated with symptomatic disease in humans (1), was present in only one strain of serotype ONT:H25. The 60-MDa plasmid was found in seven strains. Although E-hlyA was proved in seven isolates, enterohemolysin production was found in only six strains. The gene encoding EAST1, representing an additional determinant in the pathogenesis of E. coli diarrhea, was found in one strain. Two strains of serotypes O113:H4 and ONT:H25 harbored three of the four additional virulence factors tested.

TABLE 1.

Characterization results of 14 VTEC strains isolated from stool samples of 14 different asymptomatic human carriers

| Serotype | No. of isolates | Sex/workplacea | VCAb | Toxin type(s) | Virulence factor presence

|

Sorbitol/β-d-glucuronidase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eae | 60-MDa plasmid | E-hlyA | astA | ||||||

| O27:H30 | 2 | M/L | + | VT2 | − | − | − | − | + |

| O76:H19 | 1 | M/L | + | VT1 | − | + | + | − | + |

| O102:H6 | 1 | M/S | + | VT2 | − | + | + | − | + |

| O113:H4 | 1 | M/L | + | VT1, VT2 | − | + | + | + | + |

| O121:H11 | 2 | M/S | + | VT2 | − | − | − | − | + |

| O146:H28 | 1 | F/P | + | VT2 | − | − | − | − | + |

| OX178:H7 | 1 | F/BS | + | VT2 | − | − | − | − | + |

| O rough:H2 | 1 | M/C | + | VT1, VT2 | − | + | + | − | + |

| O rough:H19 | 1 | M/BS | + | VT1 | − | + | + | − | + |

| ONT:H2 | 1 | F/P | + | VT2 | − | + | + | − | + |

| ONT:H21 | 1 | M/BS | + | VT2 | − | − | − | − | + |

| ONT:H25 | 1 | F/P | + | VT1 | + | + | + | − | + |

M, male; F, female; BS, butcher shop; C, cutting; L, logistics; P, processing; S, slaughtering.

VCA, Vero cytotoxin production examined in the Vero cell assay.

The aim of further studies that are in progress is to isolate and characterize more strains. Moreover, asymptomatic human carriers should be tested over prolonged periods of time.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrett T J, Kaper J B, Jerse A E, Wachsmuth I K. Virulence factors in Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from humans and cattle. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:979–980. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.5.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutin L, Montenegro M A, Ørskov I, Ørskov F, Prada J, Zimmermann S, Stephan R. Close association of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin) production with enterohemolysin production in strains of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2559–2564. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.11.2559-2564.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bockemühl J, Karch H. Zur aktuellen Bedeutung der enterohämorrhagischen Escherichia coli (EHEC) in Deutschland (1994–1995) Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 1996;8:290–296. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnens A P, Frey A, Lior H, Nicolet J. Prevalence and clinical significance of vero-cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) isolated from cattle in herds with and without calf diarrhoea. J Vet Med B. 1995;42:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1995.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caprioli A, Luzzi I, Rosmini F, Resti C, Edefonti A, Perfumo F, Farina C, Goglio A, Gianviti A, Rizzoni G. Community-wide outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome associated with non-O157 verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:208–211. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fratamicao P M, Sackitey S K, Wiedmann M, Yi Deng M. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2188–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2188-2191.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and the associated hemotytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 1991;13:60–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson M P, Neill R J, O’Brien A D, Holmes R K, Newland J W. Nucleotide sequence analysis and comparison of the structural genes for Shiga-like toxin I and Shiga-like toxin II encoded by bacteriophages from Escherichia coli 933. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;44:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karmali M A. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:15–38. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleanthous H, Smith H R, Scotland M, Gross R J, Rowe B, Taylor C M, Milford D V. Haemolytic uraemic syndromes in the British Isles, 1885–8: association with verocytotoxin producing Escherichia coli. 2. Microbiological aspects. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:722–727. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.7.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konowalchuk J, Spiers J I, Straviric S. Vero response to a cytotoxin of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1977;18:775–779. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.3.775-779.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louie M, De Azavedo J C S, Handelsman M Y C, Clark C G, Ally B, Dytoc M, Sherman P, Brunton J. Expression and characterization of the eaeA gene product of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4085–4092. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4085-4092.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Denamur E, Milon A, Picard B, Cave H, Lambert-Zechovsky N, Loirat C, Goullet P, Sansonetti P J, Elion J. Identification of a clone of Escherichia coli O103:H2 as a potential agent of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in France. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:296–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.296-301.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostroff S M, Tarr P I, Neill M A, Lewis J H, Hargrett-Bean N, Kobayashi J M. Toxin genotypes and plasmid profiles as determinants of systemic sequelae in Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:994–999. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.6.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pérard D, Stevens D, Moriau L, Lior H, Lauwers S. Isolation and virulence factors of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in human stool samples. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:531–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reida P, Wolff M, Pohls W, Kuhlmann W, Lehmacher A, Aleksic S, Karch H, Bockemühl J. An outbreak due to enterhaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in a children day care centre characterized by person-to-person transmission and environmental contamination. Int J Med Microbiol Virol Parasitol Infect Dis. 1994;281:534–543. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley L Q, Remis R S, Helgerson S D, McGee H B, Wells J G, Davis B R, Hebert R J, Olcott E S, Johnson L M, Hargrett N T, Blake P A, Cohen M L. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:681–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303243081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt H, Rüssmann H, Schwarzkopf A, Aleksic S, Heesemann J, Karch H. Prevalence of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli in stool samples from patients and controls. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1994;281:201–213. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt H, Beutin L, Karch H. Molecular analysis of the plasmid encoded hemolysin of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1055–1061. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1055-1061.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strockbine N A, Jackson M P, Sung L M, Holmes R K, O’Brien A D. Cloning and sequencing of the genes for Shiga toxin from Shigella dysenteriae type 1. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1116–1122. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1116-1122.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandekar N C A J, Roelofs H G R, Muytjens H L, Tolboom J J M, Roth B, Proesmans W, Wolff E D, Karmali M A, Chart H, Monnens L A H. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection in hemolytic uremic syndrome in part of western Europe. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:592–595. doi: 10.1007/BF01957911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson J B, Mc Ewen S A, Clarke R C, Leslie K E, Wilson R A, Waltner T D, Gyles C L. Distribution and characteristics of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from Ontario dairy cattle. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;108:423–439. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800049931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson J B, Clarke R C, Renwick S A, Rahn K, Johnson R P, Karmali M A, Lior H, Alves D, Gyles C L, Sandhu K S, McEwen S A, Spika J S. Vero cytotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection in dairy farm families. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1021–1027. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto T, Nakazawa M. Detection and sequences of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains isolated from piglets and calves with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:223–227. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.223-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]