Abstract

Background

The growing literature on Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) and dementia identifies specific problems related to the influence that involvement has on research outcomes, over‐reliance on family members as proxies and lack of representation of seldom‐heard groups. Adaptations to the PPIE process are therefore needed to make possible the involvement of a broader spectrum of people living with dementia.

Objective

This study aimed to adapt the PPIE process to make participation in cocreation by people living with dementia accessible and meaningful across a spectrum of cognitive abilities.

Design

Narrative elicitation, informal conversation and observation were used to cocreate three vignettes based on PPIE group members' personal experiences of dementia services. Each vignette was produced in both narrative and graphic formats.

Participants

Nine people living with dementia and five family members participated in this study.

Results

Using enhanced methods and outreach, it was possible to adapt the PPIE process so that not only family members and people with milder cognitive difficulties could participate, but also those with more pronounced cognitive problems whose voices are less often heard.

Conclusions

Making creative adaptations is vital in PPIE involving people living with dementia if we wish to develop inclusive forms of PPIE practice. This may, however, raise new ethical issues, which are briefly discussed.

Patient or Public Contribution

People with dementia and their families were involved in the design and conduct of the study, in the interpretation of data and in the preparation of the manuscript.

Keywords: cocreation, dementia, graphic art, narrative, seldom‐heard groups, vignettes

1. BACKGROUND

Among the broader literature on research participation and Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) for people with dementia and their families, three specific problems have been identified that the PPIE discussed in this article attempts to address. First, the involvement of people living with dementia and family members often fails to influence the research process or outputs. Second, family members are often too heavily relied on as proxies. Finally, people living with dementia who are involved are often unrepresentative of the broader population of those diagnosed with the condition, failing to reflect the heterogeneity of dementia.

PPIE is now considered essential in health and social care research, and is increasingly a requirement of research funding bodies and publishers.1, 2 Crucial to the definition of the term PPIE is that those involved are advisors or coresearchers rather than research participants.3, 4 The extent to which PPIE group members have genuine influence on the research process is often questionable, with involvement in aspects such as design, data collection and analysis particularly limited.5, 6, 7

These concerns increase when the research relates to conditions such as dementia, which are characterised by cognitive impairment. Of 54 articles on PPIE in dementia research in a recent scoping review,8 almost all were published since 2010, indicating how recently dementia has come to the PPIE table. Few articles reviewed reported on the impact of PPIE on the dementia research process and outcomes.8 Yet, PPIE has significant potential for improving aspects of dementia research such as recruitment from seldom‐heard groups,9 and people living with dementia have said they want more opportunities to act as coresearchers.10

Coresearch involving family members is now increasingly well established.11 Despite people living with dementia having published guidance for researchers hoping to involve them in research as long ago as 2014,12 however, coresearch with people living with dementia is still comparatively rare.13, 14 In one recent study, for example, the three ‘people affected by dementia’ in a PPIE group were all current or former caregivers.15 While it is less challenging to recruit family members16 research findings indicate that people with dementia often have different views and priorities from those expressed by their relatives.17, 18, 19

In recent years, direct involvement of people living with early‐stage dementia in research processes such as data analysis workshops11 and coauthored accounts of the research process20 have become more frequent, showing that it is possible to hear the voices of people who are actually living with the condition being researched. This is not just a matter of inclusive principle, however, since without the perspectives of those living with the condition, research lacks validity and important insights may be missed.21

Attention has also been drawn to the ethical imperative to involve a more diverse range of people living with dementia in all aspects of research.22 At present, those who take an active part in PPIE are often recently diagnosed or have relatively mild cognitive difficulties, raising questions about the representativeness of the experience that is being drawn upon. Younger, recently retired members of PPIE groups are, for example, unlikely to have personal experience of the services provided to older people living with dementia who may have more pronounced cognitive difficulties and those from underserved groups are likely to have had different, possibly more extreme, experiences than those who are younger, more recently diagnosed or more socially visible.23 While recent welcome developments such as the Balanced Participation Model24 have been developed with people with early‐stage dementia, there are currently fewer models for the involvement of people with more severe cognitive difficulties.

It has been suggested that due to the challenge of involving people with more severe cognitive problems, the representativeness of the wider population with dementia may be less important than thoughtful input from lay people without this condition.25 We suggest, instead, that there is a moral requirement to create conditions under which people with dementia, including those from seldom‐heard and underserved groups, are able to contribute.22 While the involvement of people with dementia does present practical and methodological complexities,26 the onus is on researchers to adapt their methods and processes accordingly. This has already been achieved with some of the more creative approaches to research participation for people living with dementia,27 and coresearch involving people with young‐onset dementia (YOD).20 Below, we outline a PPIE project in which older people with more advanced dementia also took part, in addition to people living with YOD and family members.

1.1. The research study

The What Works in Dementia Education and Training? study, within which this PPIE project took place, was designed to identify approaches to, and characteristics of, effective training and education on dementia. Ethical approval for this study was given on 24 November 2015 by the Yorkshire and the Humber—Bradford‐Leeds NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC Ref 15/YH/0488).

We do not intend to go into detail in this article about the findings from the broader research,28, 29 but to explain the process adopted in the PPIE arm of the study and its outcomes.

1.2. Aims of the PPIE

The aims of this project were as follows: (1) to draw on the personal testimony of people with dementia and their families to facilitate discussion between researchers and health and social care practitioners in the field of dementia studies and (2) to use an enhanced range of methods to support the involvement in PPIE of people with dementia across a spectrum of cognitive abilities.

2. METHODS

2.1. Recruitment

The opportunity to take part in the PPIE group for the What Works in Dementia Training and Education? study was advertised in a regular Experts by Experience newsletter sent to members of the existing PPIE panel at one of the Universities involved in the research. The circulation list included a resource centre attended by people living with dementia. This was a site where one of the coauthors had conducted a number of previous community participatory research studies, and there were pre‐existing good relationships with both staff and people with dementia. The copy of the newsletter sent to the resource centre participants was accompanied by an additional explanatory letter to the manager asking for expressions of interest in taking part.

All those who expressed an interest in taking part, from both the general mailing list and the resource centre, were provided with an information sheet summing up the aims of the research in plain English. For the three resource centre participants considered not to have the capacity to decide whether to take part for themselves, best interests assessments were carried out, involving the manager and family members. All other participants were able to consent for themselves.

2.2. Participants

A total of fourteen participants contributed to the project discussed below. Nine members were living with dementia (six women, of whom one was Black Caribbean and one was White Irish, and three men, of whom one was White Irish). Of these, one man and one woman had YOD. The remaining five participants were family members (three men and two women, all of whom were White British).

Three of the people living with dementia (one accompanied by their spouse) took part on a University campus, together with four family members, all of whom were former carers for a spouse living with dementia.

The remaining six people living with dementia took part at the resource centre that they regularly attended during the daytime.

2.3. The PPIE process

The PPIE group met on a total of 15 occasions during the 2 years of the research study and had a varied remit during that period, including the creation of a lay summary of the literature review findings, reviewing information materials for the research participants, codesign of survey items and the creation of vignettes of their lived experience to be used in research focus groups with care staff. The process discussed in this paper relates specifically to the last of these activities.

The PPIE was cofacilitated by two coapplicants on the research study: one a family member whose spouse has dementia and one an academic researcher and educator. The roles of the cofacilitators were, generally speaking, to organise PPIE meetings, keep records, coordinate discussions, advise PPIE group members on ethical and methodological issues, liaise with the broader research team and report back to the Programme Advisory Group and funders on progress.

Several of the PPIE group members already belonged to groups affiliated to the UK Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) and one had taken part in an advisory group on the development of the DEEP guidelines on involving people with dementia in steering and advisory groups.30 We therefore followed these guidelines throughout.

An initial 1.5 h meeting was held at each of the two sites to elicit members' lived experiences of using dementia services. The meeting at the University, attended by eight people, took place in a small seminar room, with a ‘round‐table’ layout. The meeting at the resource centre, in which six people actively participated, took place in the main lounge. Although this area was also being used by other people at the same time, the room's layout, with a variety of small seating areas, made it possible to conduct discussions relatively privately. Each meeting was recorded using both written notes and audio‐recording.

To move away from more traditional methods of conducting PPIE, such as formal consultation exercises, we used a variety of narrative elicitation techniques. Narrative healthcare has attracted renewed interest in recent years, and narrative elicitation is a widely used method for embedding principles of patient‐ or person‐centredness.31 In the work of Arthur W. Frank, for example, it is recognised that when a person chooses to tell a particular story, he or she is also telling the listener about what matters most, and stories are a powerful way of amplifying the voices of those who are seldom heard.32

At the University site, oral narrative elicitation was the main method used. The following trigger questions were used:

Please think of times when you (or your relative in the case of family members) were

-

1.

Not treated equally as a person.

-

2.

Talked about using negative language.

-

3.

Talked over or ignored.

-

4.

Provided with a really good service.

-

5.

Treated in a way that added to your quality of life.

-

6.

Made to feel you belonged.

We found that participants at the University naturally adopted a storytelling approach, in which they answered the prompt questions by recalling specific incidents in considerable detail. Rather than sticking closely to the prompt questions, we therefore encouraged the participants to elaborate on these experiences, which were often recounted with a degree of dramatic performance.

[My partner] fell on the stairs and had to go to hospital. She had eleven stitches in her head. And the doctor was going to discharge her. I said, ‘Hold on; she told me she can see two of everything’. They should have tested her for concussion, but they didn't because she had dementia. [family member]

Participants at the resource centre had, in general, more difficulties with memory, comprehension and verbal expression and several also had impaired hearing. As a result, the two cofacilitators used enhanced elicitation methods at this site, including photoelicitation, informal conversation and observation. Around half of the meeting at the resource centre was spent with a small group of three participants discussing the same general subject areas as the University group. The difference here was the use of photographs to accompany the questions, for example, a photograph of a GP surgery, to accompany the question ‘How do you feel about this place?’ and an image of an older person looking bored and lonely, accompanied by ‘Does anything make you feel like this?’ These photographs had been chosen in consultation with members of the wider PPIE group to be as clear and unambiguous as possible.

We then spent approximately 20 min in informal conversation with a woman living with dementia who was sitting apart from the others and who talked in detail about her childhood home and her religious convictions. The remaining 30 min were spent observing interactions between two women sitting together in another area of the lounge.

The written notes and audio‐recorded material from both sites were transcribed by the academic cofacilitator, and key passages were discussed at several subsequent PPIE group meetings. In addition to identifying key themes, we were also interested in discovering which formats the group members felt might have maximum impact. The process by which the group decided to cocreate a series of vignettes is explained in Section Design, 3.

3. FINDINGS

At both sites, it was easier to elicit responses related to poor care than it was to identify positive experiences. It was, however, generally possible to infer what the participants wanted and expected as part of all good care practice. It was more difficult to elicit direct responses to the prompt questions at the resource centre, but those who took part still conveyed a great deal about what was important to them during general conversation and observation, using both verbal and nonverbal communication. The findings from each method are discussed below.

3.1. Narrative elicitation

Experiences of using services that the participants referred to included primary care consultations, homecare visits, memory clinic assessments, admission to hospital for acute care and community facilities such as pharmacies, supermarkets, banks and libraries.

At the University meeting, many of the comments were about microinteractions between healthcare professionals and people living with dementia, such as disparagement and invalidation.

He [a GP] said ‘Bring a carer next time, because you're not going to remember anything I tell you’. Well, I remember that! [person living with dementia]

I can't begin to tell you how fed up I am of my family being referred to as ‘carers’. My children are my children; they're not my carers. [person living with dementia]

Examples of neglect and good practice were also noted:

When [my partner] used to get agitated they used to put him in the sensory room. He didn't like the sensory room and they were sending him in there nearly every day, which I didn't realise at the time. He got to the stage where he didn't want to go there at all. [family carer]

[My partner] liked to socialise; she liked to talk to people. It helped a lot in the care home she went into, because they just let her get on with it. To me that was the most important thing, and they need to find ways to do it. [family member]

At the resource centre, the three people in the small group told us about a number of specific incidents. Brenda (all names have been changed) told us that she did not like to be rushed, and then recounted an experience with the homecare service that she received, where there was no time to choose her own clothes. Brenda pointed out that the clothes she was wearing were not her own choice:

Look at these horrible trousers. I didn't want to wear these. She just put them on me.

It was possible to draw inferences about other participants' priorities less by answers to explicit questions than by spontaneous remarks. For example, Peter was very concerned about items going missing, and we noticed that Fiona, who had been widowed some time ago, still made frequent reference to her late husband as a source of authority.

The resource centre members identified a number of experiences of having their direct choices and wishes over‐ridden. They valued being treated as individuals, feeling socially included, taking part in meaningful activity and having their concerns taken seriously. Not being allowed to do things that are perceived as dangerous by others was also a repeated theme.

3.2. Informal conversation

We spoke to Valerie, who was sitting alone in a corner of the resource centre lounge. Predetermined questions and prompts were not used, as Valerie preferred to tell us a story about her earlier life. It was possible to deduce from this a great deal about what she expected from services and what qualities were important to her in other people. She told us about growing up in St. Kitts and Nevis, about her strong religious faith and her connection with the Anglican Mission. Valerie also talked about cultural differences in food, customs and parenting practices between her homeland and the United Kingdom, in each case stating a strong preference for her country of origin.

3.3. Observation

While sitting with the remaining two women at the resource centre, we did have some conversation, but it was not directly related to their experience of dementia services. Instead, we made detailed notes about the women's (Ella and Christine's) interactions with each other, including their nonverbal communication. Both women appeared to find that sitting together added to their existing discomfort, and this seemed to go largely unnoticed by staff, who were getting the other side of the room ready for lunch. Many of Christine's comments were directed to an unseen person who seemed to be a figure of authority, and she spoke about an injury she had received treatment for. When Ella tried to join in politely, Christine tended to respond short‐temperedly, clearly upsetting Ella. With the other findings above, this interaction later became the basis of one of the three vignettes.

4. DEVELOPING VIGNETTES OF LIVED EXPERIENCE

The decision to cocreate a series of vignettes (or ‘scenarios’ as PPIE group members preferred to describe them) evolved during the process of transcribing and organising the recorded material into key themes. The findings seemed to lend themselves naturally to the development of a set of stories about the experiences that the PPIE group members had recounted. We agreed that we did not want these stories to exist solely in the form of text. Some members of the group had difficulties in processing blocks of text, and some had worked in fields where an understanding of different learning styles was important (e.g., staff development and educational welfare), so we felt it was important to use images as well.

The term vignette refers to text, images or other forms of stimuli to which people are invited to respond,33 an approach widely used in education, training and staff development. It has been noted that vignettes offer a means of unpacking complex, nuanced material and making it more accessible.34 Vignettes appear to promote high levels of engagement and empathy, with respondents often placing themselves and their experiences within the scenario.35

While a fictional vignette (VIG‐Dem) has previously been used to assess clinical skills in dementia,36 additional benefits have been identified from using nonfictional examples. It has been suggested, for example, that the use of real‐life examples enables participants to discuss matters that would usually be ‘off limits’34 and that the dramatised retelling of incidents drawn from care practice (or ‘ethnodrama’) can facilitate reflection.37 The use of vignettes is also common in problem‐based learning (PBL), where emphasis is placed on the complex nature of practice dilemmas and their solutions.38

On reviewing the recorded data, it became clear that one potential vignette centred on family members' experiences of contact with emergency services and hospital admissions. A second related to the experiences of the two group members with YOD when attending appointments with professionals in the absence of a designated ‘carer’. The final theme focused on the importance of life history awareness in formal care settings such as day and residential care.

The cocreation of the vignettes consisted of three main components: identification of the core narrative, incorporation of other narrative elements and graphic storyboarding.

4.1. Identifying core narratives

This stage involved the extrapolation of distinct storylines, weaving together dominant narrative themes that had emerged. Ongoing PPIE group discussions were used to begin drafting short narrative scenarios, which were discussed iteratively at subsequent meetings. These were eventually finalised at around 350 words each (a length that would easily fit one side of an A4 paper and have a reading time of approximately 1 min, making the vignettes reasonably accessible to research participants). Revisions to the two scenarios developed with the University group were made by the PPIE group members themselves. The third scenario, resulting from the resource centre meeting, was revised with the help of a member of the wider research team. A copy was sent to the resource centre with an invitation to comment; however, no comments were received.

The three scenarios produced are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Brief content of the scenarios cocreated with the PPIE group members

| Scenario | Description | Based primarily on |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constantin and his wife Ava arrive at the emergency department after Constantin experiences a fall at home | A family member's account of his partner's treatment in hospital |

| 2 | Nosheen, a woman living with Young‐onset dementia, visits her GP about an unrelated health problem | The experiences of two people with YOD when attending GP or memory clinic appointments |

| 3 | Ella and Christine, two women with dementia, are left to their own devices in the lounge of a care home | The experiences of six people with dementia who attend a resource centre |

Abbreviations: PPIE, Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement; YOD, young‐onset dementia.

Scenario 1, set in an Emergency Department, was based largely on a former family caregiver's account of his wife's hospital admission following a fall that had resulted in a head injury. Male and female roles were reversed in the Emergency Department scenario, and to introduce issues related to cultural diversity, the characters were also given names (Constantin and Ava) suggesting Eastern‐European origin (for the full scenario in narrative format; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Example of narrative scenario: Admission to hospital via A&E

| Constantin, aged 84, has fallen on the stairs at home and cut his forehead. He comes to A&E at 5 pm, by ambulance, with his wife, Ava. Ava explains what has happened to the triage nurse, adding that Constantin is ‘muddled in the head nowadays’. |

| A&E is very busy. Someone brought in by the police is shouting loudly. Constantin looks anxious, and whispers to Ava, ‘They're coming for me again!’ He tells Ava that he needs to go to the toilet. When he has not come out after 15 min, Ava finds a male member of staff and asks him to check. The staff member tells Ava that Constantin was hiding behind the toilet door. Constantin resists the staff who try to persuade him to leave the toilet, and they note in his records that he is ‘physically aggressive’. |

| At 9 pm, Constantin has 11 stitches put in his head. Ava is told he can now go home, but tells the nurse, ‘I'm worried that he says he can see two of me’. As a result, Constantin is kept in the hospital overnight to undergo a brain scan the following day. |

| The next morning, on the ward, Constantin is given porridge, which he does not eat. He is taken for his scan at 10 am, but it does not take place until 12.30. When he is brought back to the ward, he has missed lunch. Ava has gone home, and while she is away, Constantin is brought his teatime meal, which is left on a tray next to his bed. Constantin cannot eat without help, even though the food is something he likes this time, and 30 min later, it is taken away again. When Ava comes back, Constantin says he is hungry and thirsty. Ava tells the charge nurse, who says he will make sure Constantin gets some tea and toast as soon as visiting is over. The nurse is then sent to deal with an emergency on another ward and when he comes back at 7 pm, Constantin is asleep. |

For each scenario, a list of key points for practice improvement was also produced by the PPIE group members. For example, in Scenario 1, among 10 points in total that it was hoped health and social care practitioners taking part in the research would identify were

-

1.

Constantin appears to have double vision, and yet he is not sent for a scan.

-

2.

There seems to be a lack of recognition that his behaviour in the toilet is the result of fear.

-

3.

He is left for more than 24 h with nothing to eat.

4.2. Incorporating other narrative elements

Each scenario was based on a dominant narrative, but also incorporates elements of the experiences of other members. For example, Brian, a former family caregiver, told us about a time when unpleasant wartime memories were triggered for his wife. During WWII, she had worked as a code‐breaker and this study was so sensitive that she and her colleagues were locked in at night to prevent leaks. Her husband believed that on at least one of these occasions, she had been sexually assaulted by a guard. After developing dementia, finding the house door locked at night, she had tried to escape and neighbours who heard her shouting for help had called the police. Elements of this story are included in Scenario 1, where Constantin's traumatic memories are triggered in the Emergency Department.

Scenario 3 depicts two women sitting together with little intervention from anyone else, in the lounge of what could be a day centre or care home, in the period before lunch. The key elements of this scenario were elicited at the resource centre using a wider range of methods than Scenarios 1 and 2, including informal conversation and observation. It was therefore particularly important to make sure that the contributions of all six participants to Scenario 3 were incorporated into the final scenario. Table 3 shows how this was done.

Table 3.

Methods used to incorporate narrative elements from all PPIE group members in Scenario 3

| Narrative element | Learning point | Contributor/s | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ella lifting the fabric of her skirt and looking at it in a puzzled way | It seems that Ella does not recognise the skirt she is wearing | Peter's concern about items going missing | Narrative elicitation |

| Brenda's point about being made to wear an item of clothing that was not her own choice | Narrative elicitation | ||

| Christine having a conversation with someone who is not there, replying to herself in a different, deeper tone of voice and often mentioning someone called Bob | Bob may be a significant person in Christine's life | Interaction between Ella and Christine | Observation |

| Fiona's frequent reference to her late husband's opinions | Narrative elicitation | ||

| Ella says she wants to go home; everything was better back home when she used to help out at the Mission | Importance of knowing about life history | Valerie's comments about her homeland and religious convictions | Informal conversation |

| [A member of staff tells Ella about the lunch choices] ‘You don't like fish’, she tells Ella. Ella replies ‘I do like fish. I like saltfish. I just don't like your white fish’ | Importance of choice | Brenda and Peter both spoke about the importance of choice | Narrative elicitation |

| Valerie linked this specifically with cultural preferences | Informal conversation |

Abbreviation: PPIE, Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement.

4.3. Graphic storyboarding

All three scenarios were produced in both narrative and graphic forms. This dual format was decided on by the PPIE group members primarily as a way to engage different types of learners. As previously noted, there can be advantages to using both text‐ and image‐based scenarios depending on the groups to whom they are to be presented.33 The dementia care workforce is both multicultural and cross‐generational. Some of those encountering the scenarios would not have English as a first language, and graphical vignettes may be preferred among cultures and age groups familiar with forms such as Japanese Manga or graphic novels. There are other notable exemplars of the use of graphic novels and cartoon strip format to convey the lived experience of dementia39 and to support learning about homecare for people living with dementia.40 Although textual representation is privileged in social sciences research, it has been suggested that the engagement of other senses, including sight, is more likely to promote empathy.34

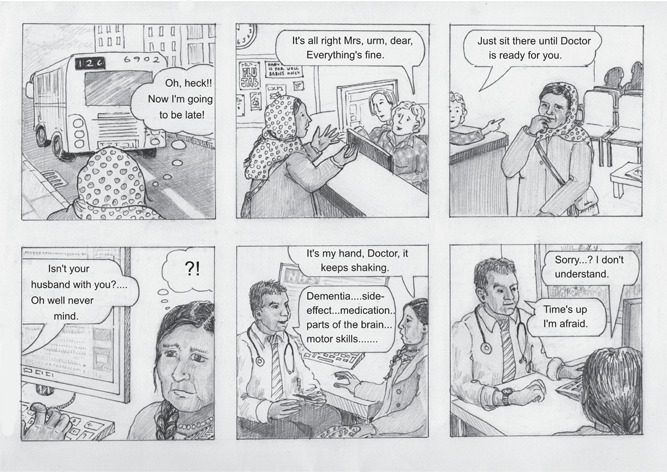

To facilitate the storyboarding process, each narrative was first broken down by the group members into six ‘mini‐scenes’ capturing its key action points. This was done first in a one‐page, six‐panel, verbal form. Table 4 demonstrates the key elements from Scenario 2 in which Nosheen visits her GP. A graphic artist whose parent was living with dementia, and who was related to a member of the PPIE group, was commissioned to carry out the corresponding artwork. Figure 1 shows the graphic novel‐style storyboard for Nosheen's GP appointment.

Table 4.

Key narrative elements: Nosheen visits her GP

| Nosheen misses the bus | Nosheen at Reception | Nosheen at Reception |

| Thinks: ‘Oh, heck! I'm going to be late’ | Receptionist: It's all right, dear… | Receptionist: Just sit there until Doctor is ready |

| GP and Nosheen | Nosheen explains about her hand | Nosheen: ‘Sorry…?’ |

| GP: ‘Isn't your | GP talking: ‘Dementia…side‐effect…medication…parts of the brain…motor skills’ | Doctor dismissive: ‘Time's up, I'm afraid’ |

| husband with you?’ |

Figure 1.

Graphic storyboard—Nosheen visits her GP. Original artwork by Kate Clarke. Copyright Leeds Beckett University.

The key elements of the stories of the two PPIE group members with YOD were kept intact in both the narrative and the graphic version: These include discriminatory assumptions made solely on the basis of diagnosis; attributing all Nosheen's symptoms to dementia (diagnostic overshadowing); taking for granted that a ‘carer’ will attend appointments along with the person with dementia; and overuse of medical terminology.

Purely fictional life history material related to people with dementia often fails to take into account the impact of national and social events, or aspects of care practice that can trigger unpleasant memories of such events. Although some details of Scenario 1 were changed, it was based on the similar experience of a real person with dementia and her reactions to such a trigger factor. Violence, imprisonment and sexual abuse are among those ‘off‐limits’ experiences of which, it has been suggested, vignettes may help to promote discussion.33

In response to Scenario 2, a primary care practitioner reflected, in response to Nosheen's visit to the GP:

You don't know how cognitively impaired she is really. You should direct the information to her anyway and make sure that someone else has the information so that …. At the same time do we know that she wants to bring someone else to her appointment? She might not.

Here, we see how a vignette might help with the development and assessment of clinical skills.36 The practitioner checks his or her own first assumptions (‘so that…At the same time’) in the process of engaging with the scenario, reflecting that passing personal information to a third party may not be appropriate without more information about Nosheen's own mental capacity.

In response to Scenario 3, a social care practitioner suggested

…maybe talking to [Ella] about the skirt, she might want to go back to her room and see if there is a skirt in her wardrobe that she would prefer to put on. Are there any social groups or activity groups that are going on that she would like to join in, or anything that she could do to help out?

Here, a subtle clue (Ella's puzzlement about her skirt—based originally on Brenda's comment about being pressured to wear trousers she did not like) is recognised as indicating either a lack of personal choice about what to wear or an indication of boredom and restlessness. Consistent with a PBL approach, where a variety of potential solutions are explored,36 the practitioner suggests improvements to practice to meet either interpretation.

4.4. Strengths and limitations of the PPIE process

Direct involvement of people with dementia in coresearch is still rare,8 so the fact that 9 of the 14 members of the PPIE group for this project were living with dementia was a positive aspect of this study. There was also a significant degree of equality between group members in the cocreation of the scenarios, with both people living with dementia and family members able to develop scenarios based on their own experiences. Membership was reasonably diverse in terms of age, gender, ethnicity and living arrangements, going some way towards addressing the need for diversity in PPIE advocated by recent sources.3, 21 Perhaps partly because of this, however, rates of attrition were also relatively high during the 2 years of the study. One of the five family members died, one person living with dementia moved to formal care and another moved out of reasonable travelling distance to be able to continue taking part by the end of the process. The resource centre also underwent some changes, and none of the six participants who took part there were still attending by the end of the wider research study.

The inclusion of older people with dementia, who also had more pronounced cognitive difficulties and were recruited via outreach work from a formal care service, remains a novel aspect of this PPIE project, as do the adapted methods that led to the scenario based on Ella and Christine. At the same time, it is possible to question whether Ella and Christine's own involvement took the form of genuine cocreation, and despite the outcome of their best interests assessments, concerns may be raised about their awareness of the nature of the process they were taking part in.

The participants at the resource centre were not involved in the subsequent development and revision of Scenario 3 in the same way as those who took part at the University. This was largely because we were concerned about matching PPIE activities to the skills and interests of individual PPIE group members, and while there were members of the University‐based group who had an appetite for this kind of work, this was less likely to be the case with others. While some resource centre participants may have been cognitively able to take part in the revision of the vignette based on Ella and Christine's experience, this would also potentially have risked breaching the two women's confidentiality. Feedback on progress with the project was provided to the resource centre, but more could have been done to facilitate the continued involvement of the six PPIE group members who took part there.

The use of anonymization to change details of gender and ethnicity may mean that the vignettes can no longer genuinely be claimed to represent the lived experience of any individual, or to have the status of real‐life examples. While this made it possible to incorporate a wider overall range of experiences and weave together narrative strands from all the participants, we acknowledge that this may have been a complex process for some group members to follow and it could have reduced their sense of ownership of the resulting scenarios. It would have been useful to carry out a more thorough evaluation of the cocreated resources, particularly, perhaps, a comparison of narrative and graphic formats. While an evaluation of the PPIE work for the What Works? Study was carried out, it did not address questions such as these, focusing more on issues such as attendance and satisfaction with consultation processes.

Producing the scenarios as graphic storyboards meant that the process shared some of the characteristics of ethnodrama, and as noted by previous authors,37 this dramatisation of everyday events made the process engaging for both the contributors and the practitioners, students and researchers with whom the scenarios were subsequently used. The characters in the graphic scenarios appear as recognisable, named individuals with distinct characteristics, appearances and lines of dialogue. This may help to humanise the content of the scenarios and to foreground person‐centred and empathic practice solutions.31

5. CONCLUSIONS

Three key problems identified in the literature on PPIE involving people with dementia are the lack of direct influence of people with dementia and their families on the research process or its outcomes, the lack of direct involvement of people with dementia by comparison with proxies and the lack of representativeness of the wider population with dementia, including those who belong to seldom‐heard groups. The PPIE work reported here attempted to address these problems in three ways: through cocreation of resources based on the personal testimony of people living with dementia and their families, by direct involvement of people living with dementia rather than reliance on proxy accounts from family members alone and by using an outreach approach and adapted methods to include people with dementia whose voices are less often heard.

Work of this nature can, however, create new ethical issues. The involvement of four of the six people at the resource centre seems to be relatively unproblematic from an ethical point of view. For the three participants who took part in the discussion group, their contribution was not a great deal different from those who took part at the University. The one‐to‐one narrative approach adopted with the fourth reflected her own preferred communication style; it demonstrated appropriate flexibility on the day and a willingness to adapt PPIE activities to individual preferences.20, 22

The involvement of the two remaining participants does, however, raise additional ethical issues. On balance, we believe that including Ella and Christine's lived experience in a fully anonymized form was the right thing to do. While we could have decided to exclude our observations from the time we spent with them, their insights into what it is like to spend time sitting in a communal lounge as a person with dementia seemed particularly valuable in the context of staff development—the focus of the research study within which this PPIE was carried out. Moreover, people like Ella and Christine rarely have any kind of voice in dementia research.

The major ethical objection is that the two women were not aware of the purpose of the exercise. This is, of course, often the case in dementia research, particularly where this relates to medical treatment. It might well be argued that we should expect higher standards for informed consent when the person's role is to influence research rather than merely to take part in it. This would, however, risk further social exclusion of those with more significant levels of cognitive impairment, whose experiences are likely to be among the most extreme and where there are currently the greatest deficits in understanding.

Research into the use of vignettes suggests that they have more impact when based on real‐life examples,34, 37 but—particularly in the context of conditions like dementia—it will often be difficult to obtain such examples with fully informed consent. Here, we face a form of a Catch‐22 ethical dilemma, in which it is harder, in equal measure, for people with severe dementia either to give consent or to have their voices heard. Codes of ethical practice on PPIE with people with dementia (or similar cognitive problems) who may lack capacity to consent for themselves therefore need to be revised taking both issues into account. It remains vitally important that people living with dementia who are less often heard continue to be directly involved in PPIE in health and social care research on dementia. Using both narrative and graphic formats to convey experiences that are ‘drawn from life’ has potential to make the resulting resources more accessible and attractive to a wider range of audiences, thereby influencing the direction of research, teaching and practice development.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Andrea Capstick, Patient and Public Involvement group co‐lead and facilitator, was involved in the analysis of focus group data and writing and preparation of the manuscript. Alison Dennison, PPI group co‐lead and facilitator, was involved in reading and contributing to drafts. Jan Oyebode, work package leader who supervised the researchers who collected the focus group data, contributed to data analysis and was involved in reading and contributing to drafts. Michelle Drury, the researcher who used the vignettes in data collection, was responsible for sharing data and reading and contributing to drafts. Sahdia Parveen, co‐applicant on the funding bid, was involved in reading and contributing to drafts. Claire Surr, Principal Investigator, was involved in reading and contributing to drafts. Lesley Healy, a member of the Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement group, contributed to the development of the vignettes. Cara Sass, the researcher who used the vignettes in data collection, was involved in reading and contributing to drafts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank 14 members of the Experts by Experience group for this study for their contributions to the process described here. The study to which the Patient and Public Involvement work discussed here contributed was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Policy Research Programme (NIHR‐PRP) under Grant PR‐R10‐0514‐120006. The views expressed are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, ‘arms length’ bodies or other government departments.

Capstick A, Dennison A, Oyebode J, et al. Drawn from life: cocreating narrative and graphic vignettes of lived experience with people affected by dementia. Health Expect. 2021;24:1890‐1900. 10.1111/hex.13332

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Littlechild R, Tanner D, Hall K. Co‐research with older people: perspectives on impact. Qual Soc Work. 2015;1:18‐35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards T, Coulter A, Wicks P. Time to deliver person‐centred care. Br Med J. 2015;350(h530):1‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) . What is public involvement in research? 2019. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/

- 4.Parkes JH, Pyer M, Wray P, Taylor J. Partners in projects: preparing for public involvement in health and social care research. Health Policy. 2014;117:399‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;5:637‐650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;8:626‐632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathie E, Wilson P, Poland F, et al. Consumer involvement in health research: a UK scoping and survey. Int J Consum Stud. 2014;1:35‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bethell S, Commisso E, Rostad H‐M, et al. Patient involvement in research related to dementia: a scoping review. Dementia. 2018;8:944‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parveen S, Barker S, Kaur R, et al. Involving minority ethnic communities and diverse Experts by Experience in dementia research: the Caregiving HOPE study. Dementia. 2018;17(8):990‐1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swarbrick C. Developing the Co‐researcher INvolvement and Engagement in Dementia Model (COINED): a participatory inquiry. In: Keady J, Hyden L‐C, Johnson A, Swarbrick C, eds. Social Research Methods in Dementia Studies. Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Loreto C, Godfrey M, Dunlop M, et al. Adding to the knowledge on patient and public involvement: reflections from and experience of co‐research with carers of people with dementia. Health Expect. 2020;23(3):691‐706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scottish Dementia Working Group Research Sub‐group . Core principles for involving people with dementia in research: innovative practice. Dementia. 2014;13(5):680‐685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevenson M, Taylor BJ. Involving individuals with dementia as co‐researchers in analysis of findings from a qualitative study. Dementia. 2017;2:701‐712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke CL, Wilkinson H, Watson J, Wilcockson J, Kinnaird L, Williamson T. A seat around the table: participatory data analysis with people living with dementia. Qual Health Res. 2018;9:1421‐1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamagnini F, Cotton M, Goodall O, et al. ‘Of Mice and Dementia’: a filmed conversation on the use of animals in dementia research. Dementia. 2018;8:1055‐1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes G, Costello H, Nurock S, Cornwall S, Francis P. Ticking boxes or meaningful partnership—the experience of lay representative, participant and study partner involvement in brains for dementia research. Dementia. 2018;8:1023‐1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyrrell J, Genin N, Myslinkski M. Freedom of choice and decision‐making in health and social care: views of older patients with early‐stage dementia and their carers. Dementia. 2006;4:479‐502. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lord K, Livingston G, Cooper C. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to and interventions for proxy decision‐making by family carers of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;8:1301‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dening KH, King M, Jones L, Vickestaff V, Sampson EL. Advance care planning in dementia: do relatives know the treatment preferences of people with early dementia? PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver K, O'Malley M, Parkes JH, et al. Living with young‐onset dementia and actively shaping dementia research—The Angela Project. Dementia. 2019;19(1):41‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crutch SJ, Yong KXX, Peters A, et al. Contributions of patient and citizen researchers to ‘Am I the right way up?’ study of balance in posterior cortical atrophy and typical Alzheimer's disease. Dementia. 2018;8:1011‐1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alzheimer Europe. Overcoming ethical challenges affecting the involvement of people with dementia in research: recognising diversity and promoting inclusive research. 2020. Luxembourg: Alzheimer Europe.

- 23.Hope K, Pulsford D, Thompson R, Capstick A, Heyward T. Hearing the voice of people with dementia in professional education. Nurse Educ Today. 2007;27(8):821‐824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thoft DS, Pyer M, Horsbøl A, Parkes J. The Balanced Participation Model: sharing opportunities for giving people with early stage dementia a voice in research. Dementia. 2018;1‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waite J, Poland F, Charlesworth G. Facilitators and barriers to co‐research by people with dementia and academic researchers: findings from a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2019;22:761‐771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poland F, Charlesworth G, Leung P, Birt L. Embedding patient and public involvement: managing tacit and explicit expectations. Health Expect. 2019;22(6):1231‐1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy K, Jordan F, Hunter A, Cooney A, Casey D. Articulating the strategies for maximising the inclusion of people with dementia in qualitative research studies. Dementia. 2014;14(6):800‐824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surr CA, Gates C, Irving D, et al. Effective dementia education and training for the health and social care workforce: a systematic review of the literature. Rev Educ Res. 2017;87:966‐1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Surr CA, Sass C, Burnley N, et al. Components of impactful dementia training for general hospital staff: a collective case study. Aging Ment Health. 2018:51‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) . Involving people with dementia as members of steering or advisory groups. Dementia Voices. 2016;15:414‐433. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naldemirci O, Britten N, Lloyd H, Wolf A. The potential and pitfalls of narrative elicitation in person‐centred care. Health Expect. 2019;23(1):238‐246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank AW. How stories of illness practice moral life. In: Goodson I, ed. The Routledge International Handbook of Narrative and Life History. Routledge; 2017:470‐480. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes R, Huby M. The construction and interpretation of vignettes in social research. Soc Work Soc Sci Rev. 2004;1:36‐51. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sampson H, Johannessen IA. Turning on the tap: the benefits of using real‐life vignettes in qualitative research interviews. Qual Res. 2020;1:56‐72. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kandemir A, Budd R. Using Vignettes to explore reality and values with young people. Forum Qual Res. 2018;19(2):Art. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spector A, Hebditch M, Stonor CR, Gibbor L. A biopsychosocial vignette for case conceptualisation in dementia (VIG‐Dem): development and pilot study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:1471‐1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kontos PC, Naglie G. Expressions of personhood in Alzheimer's: moving from ethnographic text to performing ethnodrama. Qual Res. 2006;3:301‐317. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savery JR. Overview of problem‐based learning definitions and distinctions. In: Walker A, Leary H, Hmelo‐Silver CE, Ertmer PA, eds. Essential Readings in Problem‐based Learning. Purdue Unversity Press; 2015:5‐16. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNicol SL, Leamy C. Co‐creating a graphic illness narrative with people with dementia. J Appl Arts Health. 2020;11(3):267‐280. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Husband T, Schneider J. Winston's World. University of Nottingham; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.