Abstract

During a survey of the occurrence of Malassezia species in the external ear canals of cats without otitis externa, Malassezia furfur was isolated. This is the first report of the isolation of M. furfur from cats.

The genus Malassezia consists of lipophilic yeasts which are known to be components of the microflora of human skin and many mammals and birds and are rarely isolated from the environment (11). These yeasts have the typical physiological property of using lipids as a source of carbon. Except for Malassezia pachydermatis, the remaining species of the genus Malassezia require supplementation with long-chain (C12 to C24) fatty acids for in vitro growth. The taxonomy of these yeasts has always been a matter of controversy (8). A few years ago, the species accepted were M. furfur (Robin) Baillon 1889 and M. pachydermatis (Weidman) Dodge 1935. Recently, the genus has been revised based on molecular data and lipid requirements and has been enlarged to include seven species: M. furfur, M. pachydermatis, M. sympodialis, M. globosa, M. obtusa, M. restricta, and M. slooffiae (4).

M. furfur is a known opportunistic cutaneous pathogen of humans. It is the causal agent of pityriasis versicolor, pityriasis capitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and folliculitis. Nevertheless, the importance of Malassezia species is increasing as an emergent pathogen, because they have been described to cause systemic infections in immunocompromised patients and in neonates who are receiving intravenous lipids (1, 12). The purpose of this survey was to study the lipophilic microbiota of the external ear canals of cats without otitis externa. In this paper, the first isolation of M. furfur from a cat is described.

The external ear canals of 33 house pet cats (17 male and 16 female) without otitis externa were sampled by using a swab. Samples were cultured on Sabouraud glucose agar (SGA; Biolife s.r.l., Milan, Italy), SGA supplemented with olive oil (10 ml/liter), and Leeming’s medium (10 g of peptone, 5 g of glucose, 0.1 g of yeast extract, 4 g of desiccated ox bile, 1 ml of glycerol, 0.5 g of glycerol monostearate, 0.5 ml of Tween 60, 10 ml of whole-fat cow’s milk, 12 g of agar per liter, pH 6.2) (9). All media contained 0.05% chloramphenicol and 0.05% cycloheximide. Each smear of cerumen was heat fixed, stained with Diff-Quick, and examined microscopically for the presence of typical Malassezia cells. Plates were incubated at 35°C and examined after 3, 5, 7, and 14 days. When growth was detected, five different colonies were selected from the SGA supplemented with olive oil and from the Leeming’s medium and subcultured on SGA to determinate their lipid dependence. M. pachydermatis was identified by microscopical morphology and by the ability to grow on SGA. The identification of the lipid-dependent yeasts was based on the Tween diffusion test proposed by Guillot et al. (7), the Cremophor EL assimilation test, and the splitting of esculin described by Mayser et al. (10), and the following type strains were used as controls: M. furfur CBS 1878T, M. furfur CBS 7019NT (where NT stands for neotype), M. sympodialis CBS 7222T, M. slooffiae CBS 7956T, M. globosa CBS 7966T, and M. obtusa CBS 7876T (kindly provided by E. Guého and J. Guillot). The Tween diffusion test allows differentiation between lipid-dependent species according to their abilities to assimilate various polyoxyethylene sorbitan esters (Tweens 20, 40, 60, and 80). Cremophor EL contains castor oil and ricinoleic acid and is used as an additional key character for differentiation of the species M. furfur, M. slooffiae, and M. sympodialis.

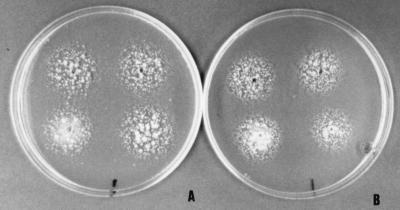

Typical Malassezia cells were evident in Diff-Quick-stained smears of cerumen from seven cats, but only five of these samples were positive by culture. Malassezia species were isolated from seven cats (21.2%), but in two Diff-Quick-stained smears from these cats, the typical Malassezia cells were not detected. Yeasts belonging to other species were not isolated. In six cats (18.1%), only M. pachydermatis was isolated during the first week of incubation (three isolates were grown at 3 days, two were grown at 5 days, and one was grown at 7 days). Only a lipid-dependent species was isolated from one cat at 7 days of incubation. This isolate formed cream, smooth, and umbonate colonies with a 4.3-mm average diameter on modified Dixon agar (36 g of malt extract, 6 g of peptone, 20 g of desiccated ox bile, 10 ml of Tween 40, 2 ml of glycerol, 2 ml of oleic acid, 12 g of agar per liter, pH 6.0) (4) after 7 days of incubation at 32°C. The texture was friable, and the cells were ovoid to spherical (1.5 to 3.0 μm by 1.5 to 4 μm). Buds were formed on a broad base, and short filaments were seen in some cells. The catalase reaction was positive. This isolate utilized the four Tweens (20, 40, 60, and 80), assimilated Cremophor EL, and was weakly positive for esculin splitting, as were the type strains M. furfur CBS 1878T and M. furfur CBS 7019NT (Fig. 1). According to these findings, this lipid-dependent yeast was identified as M. furfur (7, 10).

FIG. 1.

Tween assimilation patterns of the lipid-dependent cat isolate (A) and the type strain M. furfur CBS 7019NT (B). Note that in both cases, the four lipid sources have been assimilated. Tween 20, top left; Tween 80, top right; Tween 60, bottom left; Tween 40, bottom right.

Classically, M. furfur had been considered an anthropophilic yeast, but its isolation from different animals changed this idea (5, 6). Recently, the lipid-dependent species M. sympodialis and M. globosa have been isolated from skin and mucosae of healthy cats (2, 3). To our knowledge, this is the first report of the isolation of the lipid-dependent species M. furfur from cats. This finding confirms that healthy pet cats can also be colonized by lipid-dependent species in addition to the non-lipid-dependent species M. pachydermatis. The remaining lipid-dependent species, M. obtusa, M. restricta, and M. slooffiae, have not been reported in these animals.

Although M. pachydermatis can be isolated from the external ear canals and mucosae of healthy animals, it is more frequently isolated from dogs than from cats. In agreement with our results, Guillot et al. (5) reported percentages of M. pachydermatis isolation from the external ear canals of 20% of cats and 42% of dogs. It is known that M. pachydermatis can play an important role in chronic dermatitis and otitis externa in dogs and cats. However, it is still unclear what the role of the lipid-dependent species in their skin is. Neither has any kind of dermatitis caused by lipid-dependent species in these animals been reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barber G R, Brown A E, Kiehn T E, Edwards F F, Armstrong D. Catheter-related Malassezia furfur fungemia in immunocompromised patients. Am J Med. 1993;95:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bond R, Anthony R M, Dodd M, Lloyd D H. Isolation of Malassezia sympodialis from feline skin. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bond R, Howell S A, Haywood P J, Lloyd D H. Isolation of Malassezia sympodialis and Malassezia globosa from healthy pet cats. Vet Rec. 1997;141:200–201. doi: 10.1136/vr.141.8.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guého E, Midgley G, Guillot J. The genus Malassezia with description of four new species. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:337–355. doi: 10.1007/BF00399623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillot J, Chermette R, Guého E. Prévalence du genre Malassezia chez les mammifères. J Mycol Med. 1994;4:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillot J, Guého E. The diversity of Malassezia yeasts confirmed by rRNA sequence and nuclear DNA comparisons. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1995;67:297–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00873693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillot J, Guého E, Lesourd M, Midgley G, Chévrier G, Dupont B. Identification of Malassezia species. A practical approach. J Mycol Med. 1996;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingham E, Cunningham A C. Malassezia furfur. J Med Vet Mycol. 1993;31:265–288. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leeming J P, Notman F H. Improved methods for isolation and enumeration of Malassezia furfur from human skin. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2017–2019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.2017-2019.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayser P, Haze P, Papavassilis C, Pickel M, Gruender K, Guého E. Differentiation of Malassezia species: selectivity of Cremophor EL, castor oil and ricinoleic acid for M. furfur. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:208–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18071890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Midgley G. The diversity of Pityrosporum (Malassezia) yeasts in vivo and in vitro. Mycopathologia. 1989;106:143–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00443055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Belkum A, Boekhout T, Bosboom R. Monitoring spread of Malassezia infections in a neonatal intensive care unit by PCR-mediated genetic typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2528–2532. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2528-2532.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]