Abstract

Chromosomal exchange and subsequent recombination of the cognate DNA between bacteria was one of the most useful genetic tools (e.g., Hfr strains) for genetic analyses of E. coli before the genomic era. In this paper, yeast assembly has been used to recruit the conjugation machinery of environmentally promiscuous RP4 plasmid into a minimized, synthetic construct that enables transfer of chromosomal segments between donor/recipient strains of P. putida KT2440 and potentially many other Gram-negative bacteria. The synthetic device features [i] a R6K suicidal plasmid backbone, [ii] a mini-Tn5 transposon vector, and [iii] the minimal set of genes necessary for active conjugation (RP4 Tra1 and Tra2 clusters) loaded as cargo in the mini-Tn5 mobile element. Upon insertion of the transposon in different genomic locations, the ability of P. putida-TRANS (transference of RP4-activated nucleotide segments) donor strains to mobilize genomic stretches of DNA into neighboring bacteria was tested. To this end, a P. putida double mutant ΔpyrF (uracil auxotroph) Δedd (unable to grow on glucose) was used as recipient in mating experiments, and the restoration of the pyrF+/edd+ phenotypes allowed for estimation of chromosomal transfer efficiency. Cells with the inserted transposon behaved in a manner similar to Hfr-like strains and were able to transfer up to 23% of their genome at frequencies close to 10–6 exconjugants per recipient cell. The hereby described TRANS device not only expands the molecular toolbox for P. putida, but it also enables a suite of genomic manipulations which were thus far only possible with domesticated laboratory strains and species.

Keywords: Pseudomonas, Hfr, RP4, conjugation, genomic transfer

Before the onset of the genomics era, E. coli Hfr (high frequency of recombination) strains were used to establish the first physical maps of prokaryotic chromosomes.1 In these strains, the F plasmid integrated in the genome provided the conjugational machinery and the origin of transfer needed to mobilize large genomic stretches toward F® recipient cells. By means of interrupted conjugation experiments, a complete linkage map of different genetic markers covering the whole genome of E. coli was assembled. While the F sex factor was used for similar endeavors in Salmonella typhimurium,2 F-like plasmids were found to be functional only in the enterobacteria group.3 The discovery of new conjugative plasmids expanded those methodologies to other bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa(4) and Proteus mirabilis.5 Although such classical approaches have become obsolete nowadays, genome transfer assisted by conjugation has been recently applied in cutting-edge applications, such as the genome-wide codon replacement of E. coli driven by the hierarchical Conjugative Assembly Genome Engineering (CAGE)6 or the chromosome transplantation to E. coli minicells.7 Thus, continued exploitation of promiscuous conjugative plasmids represents a promising strategy for the development of similar genetic tools for other prokaryotes. Among the plethora of conjugative elements described so far, RP4 plasmid (also known as RK2, RP1, and the Birmingham plasmid) stands not only as a model of bacterial conjugation studied over the past 40 years, but also as one of the most conspicuous, broad-host range conjugative plasmids described in the literature. It mediates mating and plasmid transfer between a wide variety of Gram– donors/recipients8 and is also capable of efficiently conjugating with Gram+,9 yeast10,11 and mammalian cells.12 Additionally, RP4 plasmid inserted in E. coli and P. aeruginosa genomes has been reported to foster some extent of genome transfer.13,14 RP4 is a large plasmid (60 Kb), the conjugation genes of which are split in two independent regions, Tra1 and Tra2, responsible for DNA transfer (Dtr) and the mating pair formation (Mpf) functions, respectively. The mechanism of RP4 conjugational transfer is not completely understood yet, but is known to include a concerted action of different proteins of the Tra1 Core that begins when a DNA strand transferase protein, the relaxase, recognizes the sequence of oriT, nicks the DNA, and covalently binds to the 5′ end. The Tra2-encoded proteins are responsible for the pili and the mating channel formation, which brings the donor and recipient cells into intimate contact. The nascent ssDNA copy, likely replicated by a rolling-circle-like mechanism, passes through the mating bridge, and the process continues until the relaxase finds the reconstituted nick site in the incoming DNA. The ssDNA is then recircularized while the complementary strand is synthesized by the recipient-encoded replication machinery.15−20 The versatility and broad functionality of RP4 conjugation machinery led us to adopt this system as the basis for our rational design of a genetic device capable of transforming Gram– bacteria into a Hfr strain, in a manner reminiscent of the F sex factor in E. coli.

In this paper, yeast assembly was used to fuse Tra1 and Tra2 into a compact genetic cluster of ∼20 Kb, with the endogenous Tra1 gene regulation exerted by the kor genes21 substituted by the inducible expression system xylS/Pm. To allow for a simple and efficient insertion of Tra1-Tra2 into the bacterial chromosome, the assembly design included a mini-Tn5 transposon (KmR) loaded with the Tra1-Tra2 gene cluster and also a suicidal R6K plasmid backbone. The resulting pTRANS system was tested in Pseudomonas putida EM42 to confirm its potential applications in nonenterobacterial strains. Two P. putida EM42 derivatives carrying the TRANS module in different genomic loci were used as donors in mating experiments. The work explained below documents the transfer of genetic markers pyrF and edd to recipient strains of P. putida EM42 and quantifies the frequency of transfer. DNA segments ranging from 0.16 to 1.4 Mb were transmitted to the recipients at rates between 2.6 × 10–3 and 3.6 ×10–6 trans-conjugants per recipient cell, demonstrating that P. putida cells acquired a Hfr-like state upon insertion of the TRANS device. The utility of the system and the potential applications in the fields of genome shuffling, combinatorial diversification and directed evolution are considerable.

Results and Discussion

Rationale for Designing a Synthetic Genome-Mobilizing Device

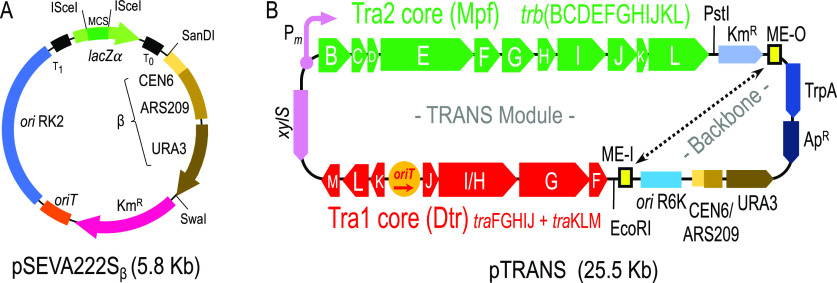

The pTRANS plasmid was designed ad hoc with the purpose of cleanly inserting the conjugational machinery of RP4 into the genome of any Gram– bacteria in order to generate a Hfr derivative. The complexity of this construct required the use of yeast assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to merge all the functional modules in a single plasmid. Because a yeast replication element was mandatory in the final construct, the yeast/bacteria shuttle plasmid pSEVA222Sβ was constructed to facilitate later construction of the pTRANS plasmid (Figure 1A): it contains three characterized SEVA modules (AbR#2, Km resistance gene; ori#2, RK2 origin of replication; cargo#2S, lacZα-pUC19/I-SceI) and a new gadget, designated as β, which includes all necessary sequences to allow replication/selection in S. cerevisiae yeast cells. The β gadget is located between SandI/SwaI sites of the SEVA backbone22 and includes the Autonomous Replication Sequence 209 (ARS209-23,24), the Centromer DNA 6 (CEN6-25) and the yeast URA3 gene.26 These three elements were edited to comply with SEVA rules27 and allow for, respectively, DNA replication, faithful segregation, and auxotrophic selection on URA® yeast strains. A detailed description of plasmid construction can be found in the Supplemental Information. In this work, pSEVA222Sβ was essentially used to amplify the β gadget for pTRANS construction.

Figure 1.

Scheme of plasmids constructed in this study. (A) Structure of the yeast shuttle vector pSEVA222Sβ: T0 and T1, transcriptional terminators; lacZα-pUC19/I-SceI with the SEVA standard multicloning site (MCS) and two ISceI sites; gadget β including yeast centromeric region CEN6, the Autonomous Replication Sequence ARS209, and the URA3 gene; KmR, kanamycin resistance gene; oriT, origin of transfer; ori RK2, origin of replication. (B) Structure of pTRANS plasmid: xylS-Pm, 3-methyl-benzoate inducible expression system; Tra2 Core region, gene cluster trb(BCDEFGHIJKL) involved in Mating Pair Formation (Mpf) functions; KmR, kanamycin resistance gene; Mosaic ends ME-O and ME-I, target sequences of TrpA; TrpA, hyperactive Tn5 transposase; ApR, ampicillin resistance gene; CEN6/ARS209/URA3, region for partitioning, replication, and selection on S. cerevisiae cells; ori RK2, origin of replication; Tra1 Core (Dtr) showing gene clusters tra(FGHIJ) and tra(KLM) together with the origin of transfer, oriT (the red arrow depicts the direction of DNA transfer during conjugation). Unique sites EcoRI and PstI are also represented.

A complete scheme of pTRANS is shown in Figure 1B, comprising several functional elements organized in a plasmid backbone (6 Kb) and the TRANS module (19.5 Kb). The plasmid backbone contains [i] a suicidal R6K origin of replication, [ii] a yeast replication/selection region CEN6-ARS209-URA (β gadget), [iii] the bla gene for ampicillin resistance (ApR), and [iv] a modified trpA gene encoding a hyperactive transposase of Tn5. The TRANS module, on the other hand, is flanked by the mosaic end sequences ME-I and ME-O (targets of the TrpA transposase in mini-Tn5 transposons28) and includes the Tra1 and Tra2 cores of RP4 plasmid as well as a KmR cassette. Tra1 core (Dtr) contains the origin of transfer (oriT) and two operons (traFGHIJ and traKLM). The protein complement of Tra1 is responsible for the oriT recognition/nicking and also mediates DNA transfer through the mating channel.15,29,30 On the other hand, the Tra2 Core (Mpf) consists of a gene cluster trbABCDEFGHIJKL, the gene products of which are involved in the mating channel and pili formation.15,19 These two regions encode the complete conjugation machinery of RP4 and are sufficient to promote DNA transfer through bacterial mating.16

The detailed assembly strategy of pTRANS is depicted in Supporting Information, Figure S1. Since the construction method relies on the homologous recombination (HR) machinery of S. cerevisiae, all DNA pieces must share homology with the adjacent DNA fragment of the final construct. Therefore, nine PCRs representing the functional elements of pTRANS were amplified, including overlapping regions of 0.5–0.8 Kb for adjacent fragments (i.e., PCRs 3 and 4 of Tra2). Additionally, five linkers were also constructed to provide homology between unrelated neighboring fragments. The Tra1 core, the expression of which is driven by overlapping promoters PtraJ and PtraK (within the oriT sequence), was amplified from RP4 by two PCRs including the transcriptional terminators flanking the divergent relaxase (traFGHIJ) and leader operons (traKLM).17 The Tra2 Core was also amplified from the RP4 template by three PCRs. The design of the Tra2 Core excluded the first gene of the cluster, trbA, the cognate operon promoters PtrbA and PtrbB and also the global regulators korA and korB. Tra2 expression is controlled by the trbA repressor and also by the products of kor genes, which in turn are involved in the regulation of a broad number of conjugation, replication, and partitioning functions of the RP4 plasmid.17,21,31 Since a proficient conjugation has been reported when Tra2 cluster is expressed from a heterologous expression system,15 the trbBCDEFGHIJKL genes were placed under the control of the xylS-Pm expression system to elicit the endogenous regulation network. xylS-Pm, the KmR cassette, and the backbone elements (ori R6K, gadget β, ApR cassette, and TrpA transposase) were recruited from SEVA collection plasmids. The DNA pool composed of PCRs1–9 and Linkers 1–5 was transformed in yeast cells and, upon selection of positive yeast clones, plasmidic DNA was isolated and subsequently transformed in E. coli. Restriction analysis and full sequencing was performed to ensure a correct assembly and sequence (see the Experimental Section for details).

pTRANS Activity in E. coli

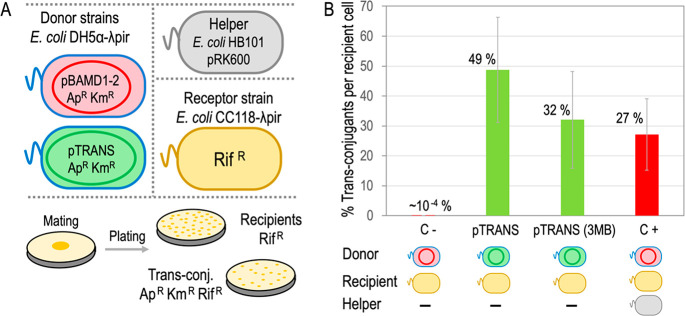

Functionality of the RP4 minimal conjugation machinery present in the hereby described genetic tool was first tested in E. coli via a conjugation efficiency assay. To this end, biparental matings between E. coli DH5α λpir (pTRANS), a donor strain sensitive to rifampicin, and E. coli CC118 λpir, a recipient strain resistant to rifampicin, were performed. Since pTRANS confers resistance to Ap and Km, selection of trans-conjugants in Ap Km Rif media and comparison with recipient cells selected in Rif media allowed for estimation of the transfer ratio of pTRANS from the donor to the recipient strain. The Tra2 cluster was designed to be inducible by 3-methyl-benzoate (3MB), so assays were conducted in both the presence and absence of the inducer. A negative control was performed with E. coli DH5α λpir (pBAMD1–2) + E. coli CC118 λpir. pBAMD1-2 (Table S1) is a R6K-based plasmid with ApR and KmR cassettes, an oriT, and also an empty mini-Tn5 transposon, thus similar to pTRANS backbone but lacking any conjugation machinery.

As a positive control, a similar mating with the last two strains and the helper strain E. coli HB101 (pRK600) was included. Results of this assays are represented in Figure 2. The negative control showed just a marginal appearance of Ap Km Rif cells (10–4%), probably due to spontaneous rifampicin mutants in the donor population. In contrast, 3MB-induced matings of pTRANS reached similar efficiencies to the positive control (∼30% trans-conjugants per recipient cell), demonstrating a remarkable performance of the condensed RP4 conjugation machinery present in pTRANS. Unexpectedly, experiments in the absence of 3MB yielded even higher values (∼50%), suggesting that the TRANS device worked in a constitutive fashion. While the reason for this unanticipated behavior is not clear, it is possible that an alternative promoter triggered the expression of Tra2 cluster. Since native control of the expression of the Tra2 cluster is unknown and may fail in some species, inclusion of the xylS/Pm inducible system (known to function in a wide variety of Gram– organisms) acts as a backup for widening the range of bacterial types that are amenable to the methodology. But this may vary with the species. Lower conjugational activity under 3MB induction could reflect in this case an excessive expression of Tra2 genes, which has been reported to greatly increase the membrane permeability to ATP, potassium, and lipophilic compounds in E. coli cells.32 Regarding the Tra1 core, PtraK seems to drive the functional expression of the traKLM operon.17 Although there is a transcriptional terminator downstream of traM, a read-through transcription from PtraK could explain the observed results. It is worth mentioning that a T insertion was spotted in the terminator sequence of the pTRANS construct, so involvement of this mutation in the termination performance cannot be ruled out. All in all, the results summarized in Figure 2 demonstrate that the TRANS device actively promotes conjugation in E. coli cells.

Figure 2.

Conjugation efficiency assay. (A) E. coli strains used in this assay are outlined: donor bacteria DH5α harboring either pBAMD1-2 (Control) or pTRANS are ApRKmR (and RifS), while the receptor strain E. coli CC118 λpir is Rif resistant. Below appears an example of mating plated in selective media to quantify receptors (LB-Rif) and trans-conjugants harboring either pTRANS or pBAMB1-2 (LB-Ap Km Rif). (B) Efficiency of conjugations are represented as the percent number of trans-conjugants (enumerated as CFUs in Ap Km Rif) per recipient cell (CFUs RifR). Donor and recipients used in each mating experiment are depicted below: negative control was performed with pBAMD1-2 donor while positive control was conducted in a triparental mating with the same donor and the mating helper strain E. coli HB101/pRK600. Conjugations with pTRANS donor were done in the presence and absence of the xylS-Pm inductor (3MB) during the mating procedure.

Genome Transfer in P. putida

The TRANS sequence contains all necessary elements to promote self-mobilization from cell to cell in E. coli, as shown in the previous section. In the assays reported below, we interrogated the ability of the system to mobilize chromosomal regions between P. putida cells. To this end, specific donor and recipient strains of P. putida EM42 (a streamlined derivative of KT244033) were constructed. As donor bacteria, a collection of strains with mini-Tn5 insertions of the TRANS module was constructed (see the Experimental Section for details).

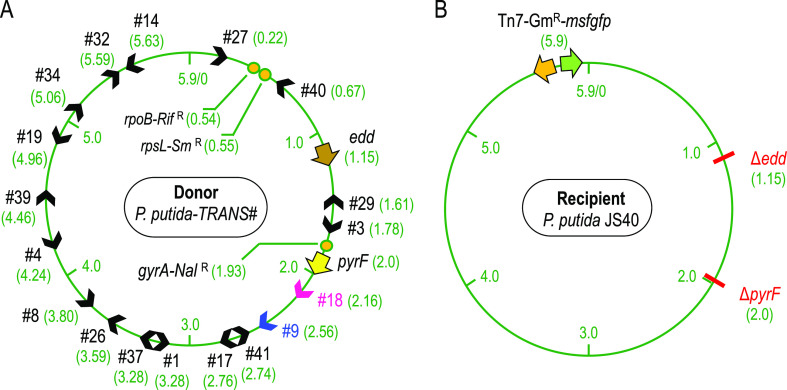

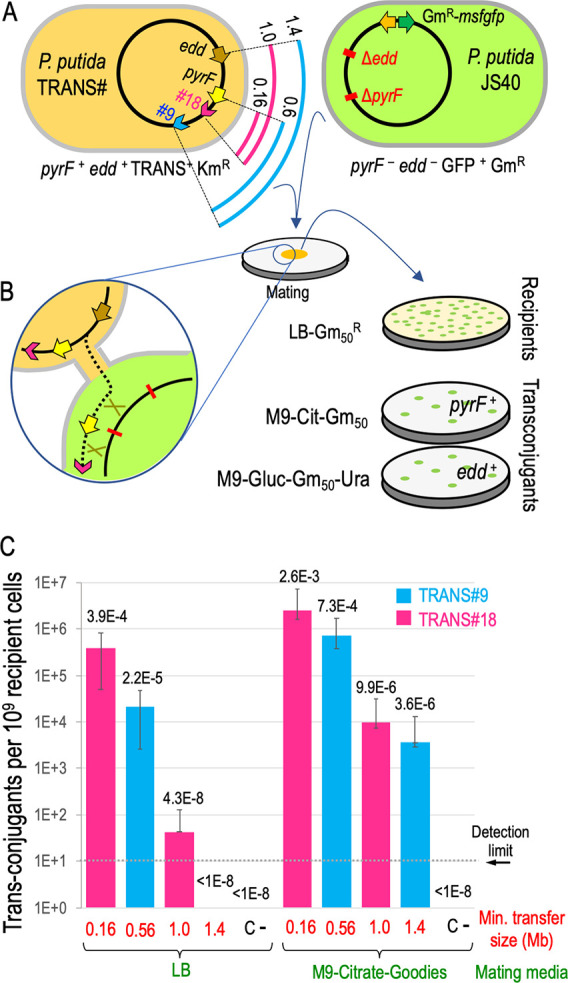

Figure 3A shows 18 P. putida-TRANS strains for which arbitrary PCR was used to identify the genomic location of their insertion. P. putida-TRANS#9 and #18 clones were selected as donors, while another derivative of EM42, P. putida JS40, was used as the receptor strain. P. putida JS40 displays constitutive expression of msfGFP, resistance to Gm and a double deletion ΔpyrF Δedd (Figure 3B). The product of the pyrF gene (PP_1815) is involved in uracil synthesis, so deletion mutants display uracil auxotrophy.34 Deletion of the edd gene (PP_1010), on the other hand, gives rise to mutants with impaired growth on glycolytic carbon sources since it encodes the first enzyme of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway of P. putida.35,36 Therefore, P. putida JS40 is an auxotroph for uracil and deficient for growth in glucose minimal media.

Figure 3.

Genomic structure of P. putida donor and recipient strains used in this study. (A) Donor: schematic view of 18 P. putida-TRANS strains carrying the TRANS module in a mini-Tn5 transposon. Arrowheads represent the insertion site and the direction of DNA transfer according to oriT orientation within the TRANS sequence. Loci coordinates in Mb appears in brackets for insertions and also for the marker genes pyrF, and edd. Mutations conferring Sm, Rif, and Nal resistances are also depicted. The strains assayed in this work, P. putida-TRANS#9 and 18, are highlighted in blue and magenta, respectively. (B) Recipient: P. putida JS40 shows a double deletion ΔpyrF Δedd and a Tn7 insertion (GmR) featuring a constitutively expressed msfGFP.

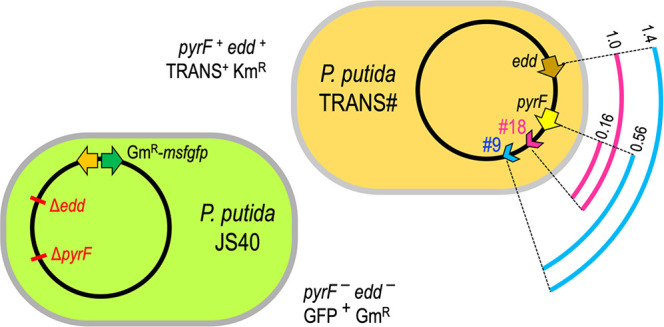

Figure S2 shows the phenotypic characteristics of donor and receptor strains on different selective media. On this background, the conjugational transfer of genomic stretches from donor strains to the double mutant receptor can be monitored by selection of trans-conjugants either on uracil-deficient media (pyrF transfer) or on media with glucose as the carbon source (edd transfer). Figure 4A represents the main features of the depicted strains, including the distance between the TRANS insertions #9 and #18 and the marker loci pyrF/edd. Figure 4B briefly outlines the theoretical mechanism of conjugal transfer: the replicative mobilization of the donor chromosome starting from the oriT of the TRANS sequence drives the nascent DNA through the cell-to-cell conjugational channel. Then, homologous recombination swaps a genomic segment into the receptor cell. Independent experiments were set up subjecting donors P. putida-TRANS#9 and P. putida-TRANS#18 to plate mating with the receptor strain P. putida JS40. A negative control using the same receptor and the donor P. putida TA280 (parental strain for donor construction lacking the TRANS module) was also done.

Figure 4.

Conjugative transference of genomic segments from P. putida-TRANS engineered strains. (A) On the left, scheme of the two donors (P. putida-TRANS#) showing the length from the TRANS insertions #9 (blue arcs) and #18 (magenta arcs) to the marker genes pyrF and edd (in Mb). Arrowheads indicate the direction of genomic transfer from the oriT. On the right, scheme of the recipient strain P. putida JS40 showing the marker gene deletions and the insertion of Tn7-GmR-msfgfp. Relevant phenotypes of depicted strains appear below. (B) Zoom-up of two mating cells sketching the conjugational transfer from P. putida-TRANS#18 to P. putida JS40. The dotted line depicts a replicating DNA strand passing through the mating bridge. Green crosses symbolize recombination events in a merodiploid recipient leading to a pyrF+ cell. Selection strategy is also shown: pyrF transfer is assayed in M9-citrate-Gm50 media (recipients able to grow without uracil), and edd transfer is assayed in M9-glucose-Gm50-Ura media (recipients growing with glucose as carbon source). (C) Efficiency of genomic transfer in two different mating media is expressed as the number of trans-conjugants per 109 recipient cells. Minimal transfer size is defined as the length between a TRANS insertion (blue for #9, magenta for #18) and the marker gene assayed. C- stands for experiments with donor strain P. putida TA280 (lacking the TRANS device). Medians and standard deviations come from three independent replicas. Absolute frequencies (trans-conjugants per recipient cell) are also shown over the bars. The detection limit was set at 10 trans-conjugants/109 recipients (1 × 10–8 trans-conjugants per recipient cell) since ∼108 recipient cells were used routinely in these mating assays.

Trans-conjugation events restoring pyrF+ or edd+ phenotypes in the receptor strain were identified by plating the mating mixture and counting CFUs, respectively, in M9-citratre-Gm50 and M9-glucose-Ura-Gm50 selective media. Colonies from both experimental sets were further analyzed by PCR to check the integrity of the marker genes in the P. putida JS40 trans-conjugants (Figure S3). The total number of receptors, on the other hand, was evaluated in LB-Gm50. Since resistance to Gm and the presence of green fluorescence were used as double criterion to identify receptor-borne CFUs, only GFP+ colonies were counted as receptors in these assays.

Notice that receptor strain displays some extent of residual growth on glucose (Figure S2): this fact accounts for the observed appearance of a background of tiny colonies in M9-Glucose-Ura-Gm50 (data not shown). Therefore, only regular-size colonies were enumerated as edd trans-conjugants. It is also worth mentioning that virtually 100% of observed colonies (either in LB-Gm50 or in selective media) displayed a clear fluorescent signal (data not shown). With transfer efficiency defined as the number of trans-conjugants per 109 receptor cells, the outcome of this exercise is represented in Figure 4C for different sizes of chromosome-mobilized regions. The minimal transfer size was defined here as the shortest DNA sequence that, once mobilized to the receptor cell, could be integrated in the P. putida JS40 chromosome by two or more events of HR. Therefore, this length was calculated for the genomic region spanning from the oriT to the assayed marker gene (pyrF+ or edd+). Results depicted in Figure 4C show that the TRANS device mediates genomic transfer between P. putida cells for chromosome regions ranging from 0.16 to 1.4 Megabase pairs (Mb). A first set of experiments was done developing the bacterial mating in LB media, but additional assays showed that M9-citrate-goodies mating media greatly improved transfer efficiencies. Genomic stretches of 0.16 Mb were transferred at absolute frequencies (trans-conjugants per recipient cell) of 3.9 × 10–4 in LB while results in M9 media reached 2.6 × 10–3. Larger regions of 0.56 and 1.0 Mb were mobilized at 7.3 × 10–4 and 9.9 × 10–6, respectively, in M9 matings. LB mating resulted in much lower frequencies of 2.2 × 10–5 (0.56 Mb) and 4.3 × 10–8 (1.0 Mb) trans-conjugants per recipient. The largest genomic region assayed (1.4 Mb) was mobilized from TRANS#9 donor using edd as the marker gene, accounting for an absolute transfer frequency of 3.6 × 10–6 in M9 media. In the case of LB mating media, no trans-conjugants could be observed, probably because the frequency of transfer fell below the assay detection limit (∼1 × 10–8). The negative control showed no trans-conjugant CFUs. The reason behind the dependence of performance efficiency upon mating media (with a differential transfer rate higher than 10-fold) is unclear, but could be due to the positive effect of trace elements (so-called goodies in the media composition) on the conjugation and DNA transfer process.

In any case, the presented results attest that regions accounting for almost 25% of P. putida genome (1.4 out of 6.0 Mb) can be successfully transferred to a recipient strain by TRANS-mediated conjugation. In E. coli, genomic transfer mediated by the F episome during CAGE assembly6 yielded frequencies of 1 × 10–4 (0.15 Mb) and 2.5 × 10–6 (half E. coli genome-2.3 Mb). F plasmid integrated in the E. coli genome has been shown to produce Hfr strains with frequencies of transfer close to 1 × 10–1,37 while E. coli laboratory strains with RP4::Mu integrations (i.e., S17–1) transfer genomic segments at 1 × 10–4.13 However, few works report genome mobilization by conjugation out of E. coli: in P. aeruginosa the conjugative plasmids FP2 and RP1 (=RP4), after spontaneous integration in the genome, generated Hfr-like strains able to mobilize genomic regions at frequencies around 1 × 10–3 (early markers) and 2 × 10–8 (late markers) recombinants per donor cell.14,38,39 In contrast, the tool hereby described expands very significantly the range of species that can be set for massive chromosomal exchanges.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that genome transfer has been programmed and verified in P. putida, demonstrating the potential of the TRANS module to generate Hfr-like strains in environmental bacteria. Given the high promiscuity of the RP4 conjugation machinery, the same strategy can be easily applied to other Gram– strains and species of interest. Unlike the use of chromosomal integrations of complete conjugative plasmids, which are difficult to obtain and show limited insertion sites in bacterial genomes, pTRANS offers the possibility of a rapid, efficient and unbiased delivery of the conjugation module along with the bacterial chromosome at stake. It cannot escape one’s notice that the ease of intraspecies and interspecies genome mobilization enabled by pTRANS opens a wide array of applications that were thus far limited to E. coli and very closely related species. Chromosomal shuffling40−42 between otherwise distant genomes appears to be a particularly appealing outlook, as it may allow combinations of desirable traits that are originally present in separate hosts.43 Furthermore, the hereby reported efficiencies of P. putida-Hfr strains, even though sufficient for many practical applications, could be improved in various ways, for example, fine-tuning of the Tra machinery expression and mutagenesis of the Tra cores44 and coexpression of factors enhancing recombination/ssDNA protection. We thus argue that the genetic tool hereby documented and its possible spinoffs will make possible an unprecedented range of genetic manipulations with nonmodel environmental bacteria.

Experimental Section

Conjugation Efficiency Assay

The ability of pTRANS to mediate autoconjugative transfer was assayed by mating E. coli DH5α λpir (Rif S) as the donor bacteria and E. coli CC118 λpir (RifR) as the recipient bacteria. Both strains encode the λpir replication protein in the chromosome and support plasmids with R6K origins of replication, but differ in Rifampicin sensitivity. E. coli DH5α λpir was first transformed with pTRANS (R6K, ApRKmR), and a pBAMD1–2 (R6K, ApRKmR) bearing strain was also constructed for positive/negative controls. Independent mating experiments were set up with recipient E. coli CC118λpir plus the donors E. coli DH5α λpir (pTRANS) and E. coli DH5α λpir (pBAMD1-2) as negative control. A positive control for conjugation was also included with a triparental mating containing E. coli DH5α λpir (pBAMD1-2), E. coli CC118 λpir, and the mating helper strain E. coli HB101 (pRK600). Bacterial strains were grown overnight in 3 mL of LB supplemented with appropriate antibiotics: Ap Km for E. coli DH5α λpir bearing either pTRANS or pBAMD1-2, Cm for E. coli HB101 (pRK600) and Rif for E. coli CC118 λpir. One milliliter of each culture was centrifuged at 11000 rpm/1 min and resuspended in 1 mL of 10 mM MgSO4. The OD600 of the resuspended samples was measured and adjusted to 1.2 with the same media. Individual experiments were set up mixing 100 μL of each strain into an Eppendorf tube. One milliliter of 10 mM MgSO4 was added, the sample was vortexed briefly, and it was centrifuged 1 min at 11000 rpm. After supernatant removal, the cellular pellet was resuspended in 10 μL of 10 mM MgSO4 by gentle pipetting. The 10–14 μL drop was placed on top of a LB-agar plate, air-dried for 10 min, and incubated 18 h at 37 °C in an upward position. For the mating of E. coli DH5α λpir (pTRANS) + E. coli CC118 λpir, both noninduced and induced experiments were performed using, respectively, LB-agar and LB-agar supplemented with 3-methyl benzoate (3MB) 1 mM. After incubation, bacterial patches were scraped out with an inoculation loop and resuspended in 1 mL of 10 mM MgSO4. Serial dilutions were prepared in the same media and plated in LB agar plates supplemented with Rif and Rif-Ap-Km. Plates were incubated 24 h at 37 °C, and colony counts were taken. Conjugation efficiency was calculated as the ratio of trans-conjugants (Ap Km Rif resistant colonies) per recipient cell (RifR colonies). Three independent replicas were performed for each experiment and the media and standard deviations were represented graphically in percentages.

Genome Transfer Assays in P. putida

The ability of P. putida TRANS#9 and P. putida TRANS#18 donors (Figure 3A) to transfer genome determinants by conjugation was assayed in biparental matings between each donor and the recipient P. putida JS40 (Figure 3B). A negative control with donor P. putida TA280 (the ancestral strain of TRANS variants, devoid of conjugation machinery in the genome) was also included. Bacterial strains were grown overnight in 3 mL of LB supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (Km for P. putida TRANS# strains, Gm50 for P. putida JS40, Sm100 for P. putida TA280). Cultures were diluted to OD600 0.1 in 20 mL of fresh LB with the same antibiotics and incubated in 150 mL Erlenmeyer flasks (30 °C/170 rpm) until they reached the exponential phase (OD6000.4–0.6). A volume of culture accounting for 0.5 units of OD600 (i.e., 1.25 mL of a sample OD600 = 0.4) was centrifuged at 11000 rpm/1 min and resuspended by gentle pipetting in 0.5 mL of washing solution (either 10 mM MgSO4 or M9-citrate-goodies, depending on the mating media assayed; see below for more details). A 0.5 mL sampling of each donor and recipient strains was pooled together in a 15 mL Eppendorf tube, briefly mixed by vortex, and centrifuged for 1 min at 11000 rpm. Supernatant was removed carefully and the pellet was resuspended in 10 μL of washing solution. The 10–14 μL drop was placed on top of an agar plate. Two different agar media were assayed for matings: LB-agar (washing media used was 10 mM MgSO4) and M9-Citrate-Goodies-agar (washing media: liquid M9-Citrate-Goodies). Samples were air-dried for 10 min and incubated 18 h at 30 °C in upward position. After incubation, the bacterial patch was recovered using a sterile inoculation loop, resuspended in 1 mL of the appropriate washing media and serial dilutions were performed in the same media. In general, dilutions 10–4–10–6 were plated in LB-Gm50 agar, while 10–1–10–3 dilutions were plated in M9-Citrate-Gm50 (selection of pyrF+ recipients) and M9-Glucose-Ura-Gm50 (selection of edd+ recipients). High Gm concentrations (50 μg/mL) were used to minimize the occurrence of spontaneous Gm resistant donors. Plates were incubated 48 h at 30 °C, and CFUs showing green fluorescence were counted. Genome transfer efficiency was calculated as the ratio of trans-conjugants (Gm50R-GFP+-pyrF+ or Gm50R-GFP+-edd+ colonies) per recipient cell (Gm50R colonies). The ratios were then normalized to 109 recipients. Three independent replicas were performed for each experiment and the media and standard deviations were represented graphically (Figure 4C). Twenty selected colonies from both types of trans-conjugants were further analyzed by PCR to check the presence of intact genes pyrF (oligos pyrF-F/pyrF-R; Tm, 52 °C; Te, 1 min) or edd (oligos edd-check-F/edd-check-R; Tm, 55 °C; Te, 1.5 min). Correct amplicon size (1.2 Kb for pyrF and 1.5 Kb for edd) was found in all trans-conjugants tested and also in the donor strain, while the receptor strain showed the expected size for pyrF and edd deletions (0.5 Kb in both cases) (Figure S3).

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dra. Almudena Fernández López for help in setting-up the yeast assembly methodology and for providing us with protocols, materials, and invaluable advice for handling S. cerevisiae. The support of the Fulbright Foundation to J.S. to her work in Spain is gratefully acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssynbio.0c00611.

Strains and media; general procedures and primers; construction of P. putida strains for genome transfer assays; yeast assembly methods and plasmid construction; assembly of pSEVA222Sβ; assembly of pTRANS; figures and tables supporting the text (PDF)

Author Present Address

# Systems, Synthetic and Quantitative Biology Ph.D. Program Harvard University, Cambridge MA 02138-3654, USA.

Author Contributions

J.S., V.d.L., and T.A. planned the experiments; J.S. and T.A. did the practical work. All Authors analyzed and discussed the data and contributed to the writing of the article.

This work was funded by the SETH (RTI2018-095584-B-C42) (MINECO/FEDER), SyCoLiM (ERA-COBIOTECH 2018-PCI2019-111859-2) Project of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, MADONNA (H2020-FET-OPEN-RIA-2017-1-766975), BioRoboost (H2020-NMBP-BIO-CSA-2018-820699), SynBio4Flav (H2020-NMBP-TR-IND/H2020-NMBP-BIO-2018-814650), and MIX-UP (MIX-UP H2020-BIO-CN-2019-870294) Contracts of the European Union and the InGEMICS-CM (S2017/BMD-3691) Project of the Comunidad de Madrid—European Structural and Investment Funds (FSE, FECER).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bachmann B. J. (1990) Linkage map of Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiol. Rev. 54, 130–197. 10.1128/MR.54.2.130-197.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson K. E.; Roth J. R. (1988) Linkage map of Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol. Rev. 52, 485–532. 10.1128/MR.52.4.485-532.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koraimann G. (2018) Spread and persistence of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes: A ride on the F plasmid conjugation module. Eco Sal Plus 8, 3. 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0003-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway B. W.; Romling U.; Tummler B. (1994) Genomic mapping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Microbiology 140, 2907–2929. 10.1099/13500872-140-11-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee J. N. (1978) Mobilization of the Proteus mirabilis chromosome by R plasmid R772. J. Gen. Microbiol. 108, 103–109. 10.1099/00221287-108-1-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs F. J.; Carr P. A.; Wang H. H.; Lajoie M. J.; Sterling B.; Kraal L.; Tolonen A. C.; Gianoulis T. A.; Goodman D. B.; Reppas N. B.; Emig C. J.; Bang D.; Hwang S. J.; Jewett M. C.; Jacobson J. M.; Church G. M. (2011) Precise manipulation of chromosomes in vivo enables genome-wide codon replacement. Science 333, 348–353. 10.1126/science.1205822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H. (2018) Regeneration of Escherichia coli from minicells through lateral gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 200, 17. 10.1128/JB.00630-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiney D. L. E. (1989) Promiscuous plasmids of Gram-negative bacteria., Academic Press, London. 10.1002/abio.370100621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trieu-Cuot P.; Carlier C.; Martin P.; Courvalin P. (1987) Plasmid transfer by conjugation from Escherichia coli to Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 48, 289–294. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1987.tb02558.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates S.; Cashmore A. M.; Wilkins B. M. (1998) IncP plasmids are unusually effective in mediating conjugation of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: involvement of the tra2 mating system. J. Bacteriol. 180, 6538–6543. 10.1128/JB.180.24.6538-6543.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann J. A.; Sprague G. F. Jr. (1989) Bacterial conjugative plasmids mobilize DNA transfer between bacteria and yeast. Nature 340, 205–209. 10.1038/340205a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters V. L. (2001) Conjugation between bacterial and mammalian cells. Nat. Genet. 29, 375–376. 10.1038/ng779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic A.; Guerout A. M.; Mazel D. (2008) Construction of an improved RP4 (RK2)-based conjugative system. Res. Microbiol. 159, 545–549. 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D.; Watson J.; Krieg R.; Leisinger T. (1981) Isolation of an Hfr donor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO by insertion of the plasmid RP1 into the tryptophan synthase gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 182, 240–244. 10.1007/BF00269664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessl M.; Balzer D.; Weyrauch K.; Lanka E. (1993) The mating pair formation system of plasmid RP4 defined by RSF1010 mobilization and donor-specific phage propagation. J. Bacteriol. 175, 6415–6425. 10.1128/JB.175.20.6415-6425.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase J.; Lurz R.; Grahn A. M.; Bamford D. H.; Lanka E. (1995) Bacterial conjugation mediated by plasmid RP4: RSF1010 mobilization, donor-specific phage propagation, and pilus production require the same Tra2 core components of a proposed DNA transport complex. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4779–4791. 10.1128/JB.177.16.4779-4791.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pansegrau W.; Lanka E. (1996) Enzymology of DNA transfer by conjugative mechanisms. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 54, 197–251. 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels A. L.; Lanka E.; Davies J. E. (2000) Conjugative junctions in RP4-mediated mating of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182, 2709–2715. 10.1128/JB.182.10.2709-2715.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkum M.; Eisenbrandt R.; Lurz R.; Lanka E. (2002) Tying rings for sex. Trends Microbiol. 10, 382–387. 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Martinez C. E.; Christie P. J. (2009) Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 775–808. 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolatka K.; Kubik S.; Rajewska M.; Konieczny I. (2010) Replication and partitioning of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2. Plasmid 64, 119–134. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García E.; Goñi-Moreno A.; Bartley B.; McLaughlin J.; Sánchez-Sampedro L.; Pascual Del Pozo H.; Prieto Hernández C.; Marletta A. S.; De Lucrezia D.; Sánchez-Fernández G.; Fraile S.; de Lorenzo V. (2020) SEVA 3.0: an update of the Standard European Vector Architecture for enabling portability of genetic constructs among diverse bacterial hosts. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D1164–D1170. 10.1093/nar/gkz1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton A. H.; Smith M. M. (1986) Fine-structure analysis of the DNA sequence requirements for autonomous replication of Saccharomyces cerevisiae plasmids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 2354–2363. 10.1128/MCB.6.7.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Gao F. (2019) Comprehensive analysis of replication origins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomes. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2122. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegemann J. H.; Fleig U. N. (1993) The centromere of budding yeast. BioEssays 15, 451–460. 10.1002/bies.950150704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M.; Botstein D. (1983) Structure and function of the yeast URA3 gene. Differentially regulated expression of hybrid beta-galactosidase from overlapping coding sequences in yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 170, 883–904. 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Rocha R.; Martinez-Garcia E.; Calles B.; Chavarria M.; Arce-Rodriguez A.; de Las Heras A.; Paez-Espino A. D.; Durante-Rodriguez G.; Kim J.; Nikel P. I.; Platero R.; de Lorenzo V. (2013) The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): a coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D666–675. 10.1093/nar/gks1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García E.; Calles B.; Arévalo-Rodríguez M.; de Lorenzo V. (2011) pBAM1: an all-synthetic genetic tool for analysis and construction of complex bacterial phenotypes. BMC Microbiol. 11, 38. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer D.; Pansegrau W.; Lanka E. (1994) Essential motifs of relaxase (TraI) and TraG proteins involved in conjugative transfer of plasmid RP4. J. Bacteriol. 176, 4285–4295. 10.1128/JB.176.14.4285-4295.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanka E.; Wilkins B. M. (1995) DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 141–169. 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer D.; Ziegelin G.; Pansegrau W.; Kruft V.; Lanka E. (1992) KorB protein of promiscuous plasmid RP4 recognizes inverted sequence repetitions in regions essential for conjugative plasmid transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 1851–1858. 10.1093/nar/20.8.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugelavicius R.; Bamford J. K.; Grahn A. M.; Lanka E.; Bamford D. H. (1997) The IncP plasmid-encoded cell envelope-associated DNA transfer complex increases cell permeability. J. Bacteriol. 179, 5195–5202. 10.1128/JB.179.16.5195-5202.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García E.; Nikel P. I.; Aparicio T.; de Lorenzo V. (2014) Pseudomonas 2.0: genetic upgrading of P. putida KT2440 as an enhanced host for heterologous gene expression. Microb. Cell Fact. 13, 159. 10.1186/s12934-014-0159-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao T. C.; de Lorenzo V. (2005) Adaptation of the yeast URA3 selection system to gram-negative bacteria and generation of a ΔbetCDE Pseudomonas putida strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 883–892. 10.1128/AEM.71.2.883-892.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarria M.; Nikel P. I.; Perez-Pantoja D.; de Lorenzo V. (2013) The Entner-Doudoroff pathway empowers Pseudomonas putida KT2440 with a high tolerance to oxidative stress. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 1772–1785. 10.1111/1462-2920.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel P. I.; Chavarria M.; Fuhrer T.; Sauer U.; de Lorenzo V. (2015) Pseudomonas putida KT2440 strain metabolizes glucose through a cycle formed by enzymes of the Entner-Doudoroff, Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas, and pentose phosphate pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 25920–25932. 10.1074/jbc.M115.687749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low B. (1968) Formation of merodiploids in matings with a class of Rec- recipient strains of Escherichia coli K12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 60, 160–167. 10.1073/pnas.60.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutit J. S. (1969) Investigation of the mating system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain 1. IV. Mapping of distal markers. Genet. Res. 13, 91–98. 10.1017/S0016672300002767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royle P. L.; Matsumoto H.; Holloway B. W. (1981) Genetic circularity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 145, 145–155. 10.1128/JB.145.1.145-155.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-X.; Perry K.; Vinci V. A.; Powell K.; Stemmer W. P. C.; del Cardayré S. B. (2002) Genome shuffling leads to rapid phenotypic improvement in bacteria. Nature 415, 644–646. 10.1038/415644a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetrapal V.; Yong L. O.; Chen S. L. (2020) Mass allelic exchange: enabling sexual genetics in Escherichia coli.. bioRxiv 405282. 10.1101/2020.11.30.405282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanopoulos G. (2002) Metabolic engineering by genome shuffling. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 666–668. 10.1038/nbt0702-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartke K.; Garoff L.; Huseby D. L.; Brandis G.; Hughes D. (2020) Genetic architecture and fitness of bacterial inter-species hybrids. Mol. Biol. Evol. msaa307 10.1093/molbev/msaa307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H.; Gunther E. (1984) High frequency FP2 donor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Mol. Gen. Genet. 197, 286–291. 10.1007/BF00330975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.