Abstract

Background

Women with heart disease are at risk for pregnancy complications, but their long‐term cardiovascular outcomes after pregnancy are not known.

Methods and Results

We examined long‐term cardiovascular outcomes after pregnancy in 1014 consecutive women with heart disease and a matched group of 2028 women without heart disease. The primary outcome was a composite of mortality, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, stroke, myocardial infarction, or arrhythmia. Secondary outcomes included cardiac procedures and new hypertension or diabetes mellitus. We compared the rates of these outcomes between women with and without heart disease and adjusted for maternal and pregnancy characteristics. We also determined if pregnancy risk prediction tools (CARPREG [Canadian Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy] and World Health Organization) could stratify long‐term risks. At 20‐year follow‐up, a primary outcome occurred in 33.1% of women with heart disease, compared with 2.1% of women without heart disease. Thirty‐one percent of women with heart disease required a cardiac procedure. The primary outcome (adjusted hazard ratio, 19.6; 95% CI, 13.8–29.0; P<0.0001) and new hypertension or diabetes mellitus (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.4–2.0; P<0.0001) were more frequent in women with heart disease compared with those without. Pregnancy risk prediction tools further stratified the late cardiovascular risks in women with heart disease, a primary outcome occurring in up to 54% of women in the highest pregnancy risk category.

Conclusions

Following pregnancy, women with heart disease are at high risk for adverse long‐term cardiovascular outcomes. Current pregnancy risk prediction tools can identify women at highest risk for long‐term cardiovascular events.

Keywords: cardiovascular, heart disease, long‐term, pregnancy

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Pregnancy, Women

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CARPREG

Canadian Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy study

- ICES

Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

- WHO

World Health Organization

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Women with heart disease are at higher risk of late postpregnancy cardiovascular complications and new hypertension/diabetes mellitus compared with women without heart disease.

Risk prediction methods developed for assessment of pregnancy risk in women with heart disease can also be used to risk stratify long‐term cardiovascular risks.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Ongoing surveillance and risk factor modification in women with heart disease beyond pregnancy is important.

Current tools for cardiovascular risk assessment during pregnancy can also be used to risk stratify for long‐term cardiovascular risk after pregnancy.

An increasing number of women with heart disease are undergoing pregnancy, with maternal cardiovascular disease estimated to affect 1% to 4% of pregnancies.1, 2 In the presence of maternal heart disease, the hemodynamic stress of pregnancy can lead to maternal deterioration, and many studies have shown that pregnant women with heart disease are at higher risk of adverse cardiac and obstetric outcomes compared with the pregnant women without heart disease,1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 While considerable progress has been made in predicting and treating cardiac complications in women with heart disease during pregnancy,9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 their long‐term cardiovascular outcomes have not been systematically examined. Determining late outcomes is important in women with heart disease, as they may be at risk for both cardiovascular deterioration after pregnancy as well as the development of hypertension or diabetes mellitus, in view of the relationship between pregnancy‐related complications and future adverse cardiovascular events.13, 15 Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to examine long‐term cardiovascular outcomes in women with heart disease after their pregnancy and compare these to a matched group of women without heart disease. We hypothesized that pregnant women with heart disease would have a higher rate of long‐term cardiovascular outcomes than pregnant women without heart disease. We also examined whether previously validated pregnancy risk prediction tools could be useful to identify those women at highest risk for long‐term cardiovascular complications.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective matched‐cohort study in Ontario, Canada, where >99% of births occur in hospitals and residents have universal access to hospital and physician services.16, 17 This study was designed by the authors, approved by the local research ethics committees, conducted at ICES (formerly Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), and reported according to recommended guidelines (Table S1). ICES is an independent, not‐for‐profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario's health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze healthcare and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. The lead author (Dr Siu) had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data‐sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access can be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca. The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

We identified and matched pregnant women with heart disease (exposure factor) who had received care at the Mount Sinai and Toronto General Hospital's pregnancy and heart disease program, with pregnant women without heart disease identified from administrative healthcare databases at ICES. We retrieved data from the following databases: (1) demographic characteristics and vital statistics from Ontario's Registered Persons Database and (2) birth outcomes from the MOMBABY database. The MOMBABY database links the hospital record of a delivering woman with that of her newborn in pregnancies that progress beyond 20 weeks' gestation or with a newborn birth weight >500 g as recorded on the Discharge Abstract Database at the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Other baseline data were determined using other ICES databases (summaries of the databases provided in Table S2). These databases have been used extensively for healthcare research including late outcome studies of pregnant women.15, 30 Neighborhood‐level income quintile and rural/urban residence were determined using Statistics Canada definitions.

We included consecutive pregnant women with preexisting heart disease (congenital, acquired, or cardiac arrhythmia) receiving care in the pregnancy and heart disease program who had at least 1 birth between 1994 (establishment of the program) and 2015 (to ensure minimum follow‐up duration of 5 years). This program provides primary and tertiary care for pregnant women with heart disease in the Greater Toronto Metropolitan area. Patients were followed until the sixth postpartum month, after which their ongoing care and follow‐up was continued by their primary physician or specialist. Details pertaining to the underlying cardiac lesion were recorded for all women at their antenatal visit.3, 4 The first pregnancy that progressed beyond 20 weeks' gestation and the corresponding birth, between 1994 and 2015, were defined as the index pregnancy and index birth, respectively. The date of the index birth was the cohort entry date. We matched the study cohort with pregnant women, also from 1994 to 2015, without heart disease or prior cardiovascular procedures, from the general Ontario population using the MOMBABY database. In women without heart disease who had multiple births during that period, a birth was randomly selected and was designated the index birth, to enable matching with women in the heart disease group who had births before 1994.

We derived a prognostic risk score to match women with heart disease to women without heart disease.31 To do so, we used the sample of pregnant women without heart disease to regress the hazard of all‐cause mortality, heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, arrhythmia, or atrial fibrillation (ie, the study's primary composite outcome) on baseline variables measured at the time of the index pregnancy (comorbid conditions, fertility therapy, ethnicity, multifetal births, cesarean delivery, gestational diabetes mellitus, and site of delivery; Table S3). To create the community comparison group of women without heart disease, women without heart disease were matched to each woman with heart disease on the following: (1) prognostic risk score ±0.2 SDs, (2) age at index birth ±1 year, (3) same fiscal year of index birth, (4) any births before index birth, (5) residence in metropolitan area (Toronto), and (6) income quintile. Using these 6 factors, we matched each pregnant woman with heart disease to 2 pregnant women without heart disease with the same predicted risk of subsequently developing the composite outcome based on demographic and baseline variables. This strategy of 1:2 matching was to improve the precision of the risk estimates in the matched groups without a commensurate increase in bias.32

Covariate Conditions and Pregnancy Risk

Covariate conditions and outcome were obtained using diagnostic or procedural codes from the International Classification of Disease Ninth Revision (ICD‐9); International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Tenth Revision, Canada (ICD‐10‐CA); Canadian Classification of Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Surgical Procedures; Canadian Classification of Health Interventions; and the above‐mentioned ICES databases (Table S4). Covariate conditions and outcome were defined before data analysis, as per ICES policy.

In the heart disease group, antepartum cardiac variables and diagnosis were used to calculate the maternal cardiovascular risk during the index pregnancy using 3 validated risk classification methods in current use that are applicable to women with a range of cardiac conditions: the original CARPREG (Canadian Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy) risk score,3 the expanded CARPREG II risk score,4 and the modified World Health Organization (WHO) classification system.14 These risk classification methods estimate the mother's baseline cardiovascular risk during pregnancy and the first 6 postpartum months (Table S5). Using each method, women in the heart disease group were classified as either low or intermediate‐to‐high risk for maternal cardiovascular complications during their index pregnancy.

Outcomes

Women were followed until death or end of the follow‐up period (December 31, 2019), whichever occurred earlier. The primary outcome was a composite of all‐cause mortality, heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, arrhythmia (including cardiac arrest, ventricular and atrial tachyarrhythmia, and heart block), or atrial fibrillation. The secondary outcomes were (1) components of the composite primary outcome, (2) cardiovascular death, (3) therapeutic cardiac procedures (catheter based or surgical), and (4) incident hypertension or diabetes mellitus. For determination of outcomes, cardiovascular events that occurred during the antepartum period or within the first 6 postpartum months were considered to be pregnancy related, as changes in the maternal cardiovascular system do not fully resolve until this time has elapsed.4, 33 The validated algorithms for incident diabetes mellitus and incident hypertension exclude gestational diabetes mellitus or hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.25, 28

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) at ICES. Continuous variables were summarized using the median and interquartile range. To comply with ICES's privacy policy, we suppressed frequency counts between 1 and 5. We compared baseline characteristics between women in the heart disease and comparison groups using standardized differences, with a value ≥0.10 considered a potentially important difference. Unadjusted cumulative incidence curves of outcomes (which accounted for the appropriate competing risk when necessary) were generated.

We fit separate Cox regression models to compare primary and secondary outcomes between heart disease and comparison groups. When there were competing risks (mortality not included as an outcome), cause‐specific regression models were used instead of Cox regression. The covariates for each model included heart disease status, any obstetric complication (ie, ante‐ or postpartum hemorrhage, placental abruption, placental infarction, premature delivery or rupture of membranes, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia/eclampsia, poor fetal growth, or stillbirth) during the index pregnancy, any cardiac complication (heart failure, arrhythmia, stroke, or myocardial infarction) during the index pregnancy, fetal congenital heart defect during index pregnancy, Charlson Comorbidity Index,34 and the baseline demographic variables used in matching (age and fiscal year of index birth, any births before index birth, residence in Toronto metropolitan area, income quintile). Covariates relating to outcome of the index pregnancy (obstetric complications, cesarean delivery, and congenital heart disease in the infant) were included because of their relationship to subsequent cardiovascular disease in the general population.13, 15, 35, 36, 37 As the matching process may not balance all covariates including comorbid diagnoses, we adjusted for residual confounding by using the Charlson Index, as well as the demographic variables used in the matching process. The model also included 2 time‐varying covariates for births subsequent to index pregnancy (currently pregnant; number of births after the index birth), to adjust for the possible influence of subsequent pregnancies on outcomes. If the hazard ratio associated with the variable of interest (heart disease group) did not meet the proportional hazard assumption, we computed time‐specific instantaneous hazard ratios by inclusion of a time interaction term into the models. Level of significance was set at 0.05 (two sided).

Adjusted cumulative incidence curves were generated from the Cox regression (when mortality was included in the outcome) or Fine‐Gray models (when mortality was not included as an outcome); time‐varying covariates were not included in these models, as cumulative incidence functions cannot be estimated in the presence of time‐varying covariates.38 We repeated the above procedure by using CARPREG, CARPREG II, and WHO risk groups (low versus intermediate‐to‐high risk for pregnancy maternal cardiovascular complications) in place of the heart disease group variable.

Cumulative incidence curves were truncated at the time of follow‐up, beyond which the total number of women at risk was ≤20% of the baseline. Ninety‐five percent CIs were calculated using 1000 bootstrap samples. A robust variance estimator was used to account for the matched nature of the sample.

Results

A total of 1036 women with heart disease were eligible for matching after excluding pregnancy‐associated deaths (n=1–5, exact number suppressed because of ICES's privacy policy) and applying other exclusion criteria (Figure S1). After applying the matching algorithm, 1014 women with heart disease were successfully matched to 2028 women in the comparison group. The median age at the time of the index birth was 30 years in both groups. At the time of the index birth, a higher proportion of the heart disease group had a Charlson score ≥1, delivered at a tertiary care center, had an infant born with congenital cardiac defect, or had a cardiovascular complication during pregnancy, when compared with the comparison group; the 2 groups were not significantly different with respect to other characteristics (Table 1). In the heart disease group, the most frequent maternal cardiac lesions were congenital heart defect and left‐sided valvular disease.

Table 1.

Baseline and Follow‐Up Characteristics in Women With Heart Disease and Matched Comparison Group

| Heart Disease Group (n=1014 Women) | Community Group (n=2028 Women) | Standardized Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At index birth | |||

| Median (IQR) maternal age, y | 30.0 (27.0–34.0) | 30.0 (27.0–34.0) | 0 |

| Low residential income area,* n (%) | 415 (40.9) | 830 (40.9) | 0 |

| Rural residence, n (%) | 45 (4.4) | 94 (4.6) | 0.01 |

| Residence within metropolitan area,† n (%) | 635 (62.6) | 1270 (62.6) | 0 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Chinese | 47 (4.6) | 92 (4.5) | 0 |

| South Asian | 39 (3.8) | 68 (3.4) | 0.03 |

| Not Chinese or South Asian | 928 (91.5) | 1868 (92.1) | 0.02 |

| Any comorbid condition,‡ n (%) | 450 (44.4) | 846 (41.7) | 0.05 |

| Charlson Index ≥1, n (%) | 79 (7.8) | 22 (1.1) | 0.33 |

| Fertility treatment, n (%) | 38 (3.7) | 66 (3.3) | 0.03 |

| Any previous births, n (%) | 299 (29.5) | 598 (29.5) | 0 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 59 (5.8) | 155 (7.6) | 0.07 |

| Multifetal pregnancy, n (%) | 28 (2.8) | 49 (2.4) | 0.02 |

| Delivery at tertiary center, n (%) | 912 (89.9) | 1345 (66.3) | 0.6 |

| Cesarean delivery, n (%) | 295 (29.1) | 598 (29.5) | 0.01 |

| Preterm birth, n (%) | 132 (13.0) | 221 (10.9) | 0.07 |

| Stillbirth, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1–5 (0.1–0.2) | 0.03–0.07 |

| Obstetric complication during index pregnancy,§ n (%) | 303 (29.9) | 536 (26.4) | 0.08 |

| Cardiac complication during index pregnancy,‖ n (%) | 65 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.37 |

| Infant born with congenital cardiac lesion, n (%) | 91 (9.0) | 35 (1.7) | 0.33 |

| Primary maternal cardiac diagnosis,¶ n (%) | |||

| Congenital | 399 (39.3) | ||

| Cardiomyopathy | 112 (11.0) | ||

| Left‐sided valve disease | 312 (30.8) | ||

| Isolated arrhythmia | 118 (11.6) | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 26 (2.6) | ||

| Other | 47 (4.6) | ||

| After index birth | |||

| Median (IQR) follow‐up, y | 13.7 (8.6–19.8) | 14.0 (8.8–20.2) | 0.05 |

| Range | 0.9–25.2 | 3.8–25.7 | |

| Number of women with subsequent births, n (%) | 493 (48.6) | 869 (42.9) | 0.12 |

| Number of subsequent pregnancies | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | 0.13 |

| Range | 0.00–8.00 | 0.00–5.00 | |

| Median (IQR) interval between index birth and next subsequent birth, y | 2.9 (2.1–4.4) | 2.9 (2.1–4.4) | 0 |

IQR indicates interquartile range.

Residing within the 2 lowest neighborhood income quintiles.

Residence within Greater Toronto Metropolitan Area.

Any comorbid condition (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, renal disease, cancer, collagen vascular disease, thyroid disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, dyslipidemia, obesity, or substance abuse).

Admission within 9 months before and including index birth, for ante‐ or postpartum hemorrhage, placental abruption, placental infarction, premature delivery or rupture of membranes, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia/eclampsia, poor fetal growth, or stillbirth.

Admission within 9 months before and 6 months after index birth, for heart failure, arrhythmia, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

In women with multiple cardiac lesions, the diagnosis that is the most hemodynamically significant was considered to be the primary diagnosis. Lesions that do not fall into the first 5 mutually exclusive categories were classified as other.

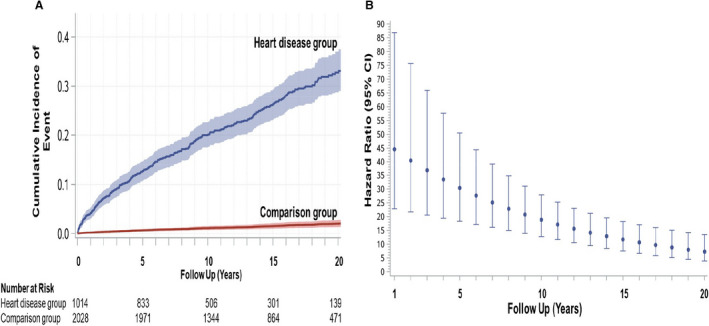

The maximum follow‐up duration was 25 years in both groups, with a total of 14 416 and 29 414 person‐years' follow‐up for the heart disease group and comparison group, respectively. Median follow‐up duration in the heart disease (13.7 years; interquartile range, 8.6–19.8 years) and comparison group (14.0 years; interquartile range, 8.8–20.2) were similar (Table 1). Data collection was complete for all outcomes. A primary outcome occurred in 298 women in the heart disease group (25.3 events/1000 person‐years) versus 32 women in the comparison group (1.1 events/1000 person‐years) with an adjusted hazard ratio of 19.6 for the entire follow‐up period (Table 2). The adjusted cumulative incidence of a primary outcome in the heart disease group was 20.1% at 10 years and 33.1% at 20 years of follow‐up; the corresponding cumulative incidence was 2.1% in the comparison group at 20 years of follow‐up (Figure 1A). There was a time dependency to this elevated hazard for the primary outcome, with the highest hazard ratios in the earlier years of follow‐up after delivery (Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Frequency and Rate of Adverse Outcomes in Women With Heart Disease and Matched Comparison Group

|

Heart Disease n=1014 Women |

Comparison n=2028 Women (Referent) |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value for Adjusted HR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Rate per 1000 Person‐Years (95% CI) | n (%) | Rate per 1000 Person‐Years (95% CI) | ||||

| Composite outcome | 298 (29.4) | 25.4 (22.7–28.4) | 32 (1.6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 24.0 (16.6–35.0) |

19.6 (13.8–29.0)* See Figure 1B for time dependent HRs |

<0.0001 |

| All‐cause mortality† | 43 (4.2) | 3.0 (2.2–4.0) | 14 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 6.8 (3.6–12.7) | 5.4 (2.9–10.4)* | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure† | 117 (11.5) | 8.7 (7.2–10.4) | 1–5 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 65.8 (25.4–240.1) | 45.7 (20.6–129.8)* | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation† | 205 (20.2) | 16.5 (14.4–18.9) | 9 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 61.8 (31.3–128.3) |

44.7 (24.2–94.5)* Year 1: 153.4 (39.4–597.0) Year 5: 89.2 (31.9–249.6) Year 10: 45.3 (21.7–94.8) Year 15: 23.0 (10.9–48.5) |

<0.0001 |

| Arrhythmia† | 142 (14.0) | 10.8 (9.17–12.72) | 1–5 | 0.07‡ | 184.7‡ | § | |

| Myocardial infarction or stroke† | 23 (2.3) | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | 8 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 7.0 (2.9–16.5) | 5.6 (2.5–13.6) | 0.0001 |

| Therapeutic cardiac procedures | 281 (27.7) | 24.3 (21.7–27.3) | 8 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 105.2 (50.1–245.4) |

83.7 (44.2–184.9)* Year 1: 314.0 (76.3–1292.3) Year 5: 179.8 (59.4–544.6) Year 10: 89.6 (39.7–202.2) Year 15: 44.6 (21.3–93.4) |

<0.0001 |

| New diabetes mellitus or hypertension | 209 (20.6) | 17.5 (15.3–20.0) | 274 (13.5) | 10.7 (9.5–12.0) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 1.6* (1.4–2.0) | <0.0001 |

HR indicates hazard ratio.

Hazard ratio from analyses assuming constant proportional hazard between heart disease and comparison groups, instantaneous hazard ratios at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years are provided when proportional hazard assumption was not met.

Secondary outcomes are not mutually exclusive.

95% confidence intervals not provided as per Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences' privacy policy for low counts.

Time‐dependent hazard ratios not calculated because of low number of events in the comparison group.

Figure 1. Adjusted time‐to‐event curves for primary outcome and hazard ratios.

A, Adjusted cumulative incidence of the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality, heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, arrhythmia, or atrial fibrillation) with 95% CIs in the heart disease group and matched comparison group. Numbers at risk were obtained from unadjusted cumulative incidence curves. B, Instantaneous hazard ratio (point estimates and 95% CIs) of primary outcome in heart disease group (comparison group=referent) as a function of follow‐up time.

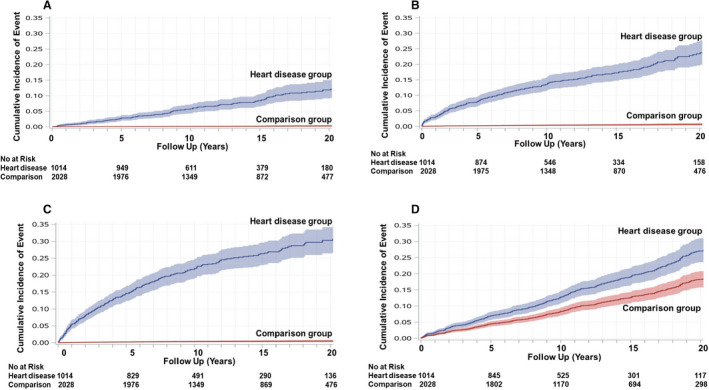

The adjusted rates for all‐cause mortality, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or stroke were higher in the heart disease group compared with the comparison group (Table 2). The rate of cardiovascular death was 1.0 per 1000 person‐years in women with heart disease and 0.04 per 1000 person‐years in controls (crude hazard ratio, 20.3; adjusted hazard ratio not calculated because of very low rate in the comparison group). At 20 years of follow‐up, the heart disease group had a higher adjusted cumulative incidence of heart failure and atrial fibrillation compared with the comparison group (Figure 2A and 2B). The heart disease group also frequently required therapeutic cardiac procedures (30.6% at 20 years) and developed new hypertension or diabetes mellitus (27.2% at 20 years), both of which were higher than in the comparison group (0.5% and 18.4%, cardiac procedures and incident hypertension/diabetes mellitus, respectively) (Figure 2C and 2D). Unadjusted cumulative incidence curves (Figures S2 and S3) showed similar trends as adjusted curves.

Figure 2. Adjusted time‐to‐event curves for selected secondary outcomes.

Adjusted cumulative incidence and 95% CIs for selected secondary outcomes (heart failure [A], atrial fibrillation [B], therapeutic cardiac procedures [C], and new hypertension or diabetes mellitus [D]) in heart disease group and matched comparison group. Numbers at risk were obtained from unadjusted cumulative incidence curves.

In a secondary analysis, in which the cumulative incidence of primary outcomes was stratified by the occurrence of cardiac or obstetric complications during the index pregnancy (Figure S4), the unadjusted cumulative 20‐year incidence of a primary outcome in women with heart disease who experienced a pregnancy complication was 48.5% compared with 32.5% in women with heart disease who did not experienced a pregnancy complication. In comparison, the cumulative incidence in women from the comparison group was 3.6% and 2.1%, with and without pregnancy complications, respectively. When atrial fibrillation and arrhythmia were excluded from analysis, the adjusted cumulative incidence of all‐cause mortality, heart failure, stroke, or myocardial infarction at 20 years was 15.0% and 1.4% in the heart disease and comparison groups, respectively (Figure S5). The unadjusted rate of the primary outcome and the frequency of the component events, stratified by principal cardiac diagnosis, are provided in Table S6.

Maternal heart disease was associated with an elevated hazard for the primary composite outcome or cardiac procedure even after adjustment for the statistically significant covariates such as cardiac complications during pregnancy and maternal age (Table 3). Similarly, the elevated hazard for incident hypertension and diabetes mellitus associated with maternal heart disease was after adjustment for statistically significant covariates including obstetric complications during pregnancy, baby born with congenital heart disease, maternal age, low residential income area, and nulliparity. The inverse relationship between fiscal year of birth and outcomes can be attributed to the shorter follow‐up time for women with more recent births.

Table 3.

Adjusted Model for Primary Outcome, Cardiac Procedures, and New Hypertension/Diabetes Mellitus

| Parameter | Primary Composite Outcome | Cardiac Procedure | New Hypertension or Diabetes Mellitus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Heart disease group (community comparison group=referent) |

19.6 (13.8–29.0)* See Figure 1B for time‐dependent HRs |

<0.001 |

83.7 (44.2–184.9)* See Table 2 for time‐dependent HRs |

<0.001 | 1.6 (1.4–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Obstetric complication during index pregnancy | 1.25 (1.0–1.6) | 0.072 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.36 | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac complication during index pregnancy | 3.3 (2.3–4.6) | <0.001† | 1.9 (1.3–2.8) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.98 |

| Infant born with congenital cardiac lesion | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 0.12 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 0.15 | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.023 |

| Number of subsequent pregnancies | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.50 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.090 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.38 |

| Any subsequently pregnancies | 2.0 (1.3–3.0) | 0.0030† | 0.39 (0.16–0.79) | 0.020 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.019 |

| Charlson Index score ≥1 | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) | 0.068 | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.68 | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.21 |

| Age at index birth | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 0.0016 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.29 | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | <0.0001 |

| Low residential income area | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.77 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.42 | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 0.0001 |

| Greater Toronto metropolitan area residence | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.87 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.28 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.14 |

| Index birth is first pregnancy | 0.8 (0.7–1.1) | 0.16 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.41 | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) | 0.014 |

| Fiscal year of index birth | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.039† | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.0033 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.0010 |

HR indicates hazard ratio.

hazard ratio from analyses assuming constant proportional hazard between heart disease and comparison groups.

After the index birth, there were additional births in 48.6% of the heart disease group and 42.9% of the comparison group, with a median time of 2.9 years between the index and subsequent birth in both groups (Table 1). There was no significant relationship between number of subsequent births and the primary outcome (Table 3). The hazard of having a primary outcome was increased during the time of subsequent pregnancy (Table 3). However, only 11.4% of the primary outcomes in the heart disease group occurred during subsequent pregnancies (none in the comparison group); these events were either heart failure, atrial fibrillation, or arrhythmia. Similarly, 2.4% of cardiac therapeutic procedures performed in the heart disease group (none in the comparison group) were in relation to subsequent pregnancies.

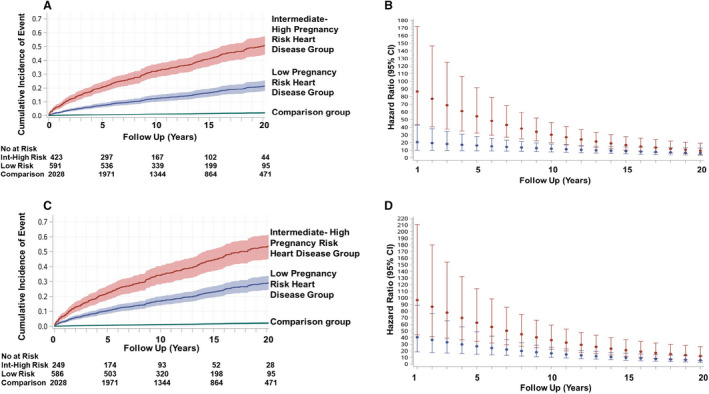

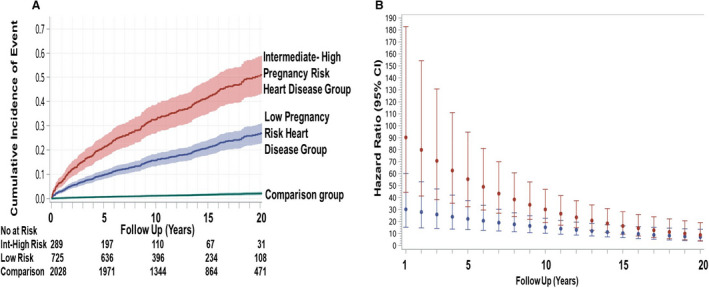

Table 4 provides a summary of pregnancy risk groups stratified by maternal cardiac lesions. The proportion of the heart disease group at intermediate‐to‐high risk for cardiovascular complications during their index pregnancy was 42%, 29%, and 30%, corresponding to CARPREG risk score >1, CARPREG II risk score ≥4, and WHO class III or IV (estimated cardiovascular pregnancy risk of ≥27%, >22%, and ≥19%, respectively). Women at intermediate‐to‐high pregnancy risk were also at the highest risk of experiencing a primary outcome during follow‐up (Figures 3 and 4). This finding was consistent regardless of the pregnancy risk classification tool that was used (Table S7, Figures 3A, 3C, and 4A). The adjusted cumulative incidence of a primary outcome at 20 years was 50.6%, 51.0%, and 53.6% when intermediate‐to‐high pregnancy risk groups were defined using CARPREG, CARPREG II, and WHO classification tools, respectively. While the risk of a primary outcome was elevated during the early years of follow‐up in both pregnancy risk groups, women in the intermediate‐to‐high pregnancy risk group had the highest risk (Figures 3B, 3D, and 4B). When the data were reanalyzed using separate WHO classes, the results were similar to when the WHO classes were combined into high and low‐to‐intermediate categories. The adjusted cumulative incidence of a primary outcome in women in WHO classes III and IV was 52.8% to 54.2% at 20 years, compared with 12.5% for women in WHO class I. In contrast, the comparison group's corresponding cumulative incidence was 2.1% (Figure S6).

Table 4.

Principal Cardiac Lesion in Heart Disease Group and Maternal Cardiovascular Risk at Time of Index Pregnancy

| Maternal Cardiac Lesion | Total No. | Maternal Cardiovascular Risk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARPREG Risk Score* | CARPREG II Risk Score† | WHO Classification ‡ , § | |||||

|

Low Risk n (%) |

Intermediate‐to‐High Risk n (%) |

Low Risk n (%) |

Intermediate‐to‐High Risk n (%) |

Low Risk n (%) |

Intermediate‐to‐High Risk n (%) |

||

| Congenital | 399 | 334 (83.7) | 65 (16.3) | 365 (91.5) | 34 (8.5) | 283 (77.3) | 83 (22.7) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 112 | 36 (32.1) | 76 (67.9) | 42 (37.5) | 70 (62.5) | 47 (42.0) | 65 (58.0) |

| Left sided valve | 312 | 161 (51.6) | 151 (48.4) | 230 (73.7) | 82 (26.3) | 173 (72.4) | 66 (27.6) |

| Isolated arrhythmia | 118 | 0 | 118 (100) | 34 (28.8) | 84 (71.2) | 69 (71.9) | 27 (28.1) |

| Ischemic | 26 | 21–25‖ | 1–5‖ | 14 (53.8) | 12 (46.2) | 6–10‖ | 1–5‖ |

| Other | 47 | 35–40‖ | 10–15‖ | 40 (85.1) | 7 (14.9) | 5–10‖ | 5–10‖ |

| Total | 1014§ | 591 (58.3%) | 423 (41.7%) | 725 (71.5) | 289 (28.5) | 586 (70.2) | 249 (29.8) |

CARPREG indicates Canadian Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy study; and WHO, World Health Organization.

CARPREG Risk Score: low risk=5%, intermediate‐to‐high risk = ≥25%.

CARPREG II Risk Score: low risk=5% to 15%, intermediate to high risk = ≥22%.

Modified WHO: low risk=2.5% to 19% (WHO class I, II, III–III), intermediate‐to‐high risk = ≥19% (WHO class III or IV).

Total patients n=835 for WHO groups as cardiac lesions in 179 patients could not be classified into a WHO risk group.

Exact numbers not provided because of Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences' privacy policy.

Figure 3. Pregnancy risk groups: adjusted time‐to‐event curves for primary outcome and hazard ratios.

Adjusted cumulative incidence of primary outcome and 95% CIs as a function of maternal cardiovascular risk during index pregnancy. Incidence rates are separated into low pregnancy risk heart disease group vs intermediate‐to‐high pregnancy risk heart disease group, as defined by the CARPREG (Canadian Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy) risk score (A),3 and the modified World Health Organization classification system (C).14 Numbers at risk were obtained from unadjusted cumulative incidence curves. Comparison group denotes matched community comparison group. Instantaneous hazard ratios (point estimates and 95% CIs) for the low (in blue) and intermediate‐to‐high (in red) pregnancy risk groups corresponding to the CARPREG risk score (B) and WHO (D) risk classification are shown (comparison group=referent).

Figure 4. CARPREG (Canadian Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy) II adjusted time‐to‐event curves for primary outcome and hazard ratios.

A, Adjusted cumulative incidence of primary outcome (with 95% CIs) as a function of maternal cardiovascular risk during index pregnancy in the low pregnancy and intermediate‐to‐high (Int‐High) pregnancy risk heart disease groups, as defined by the CARPREG II risk score.4 Comparison group denotes matched community comparison group. No at risk denotes number at risk from unadjusted cumulative incidence curves. B, Instantaneous hazard ratios (with 95% CIs) of primary outcome (matched community group=referent) as a function of time, in the low (in blue) and intermediate‐to‐high (in red) risk groups corresponding to the CARPREG II risk score.

Discussion

In this large study of women with heart disease, adverse cardiovascular events occurred in ≈1 in 3 women during the 20 years following pregnancy, representing a 20‐fold increase in risk when compared with a matched group of women without heart disease. Furthermore, many women with heart disease required therapeutic cardiac procedures during this same period. Women with heart disease were also more likely to develop new hypertension or diabetes mellitus when compared with women without heart disease. Risk stratification tools used to predict cardiovascular complications in pregnant women with heart disease, such as the CARPREG risk score or the WHO classification, were also helpful in identifying those women at highest risk of long‐term cardiovascular complications.

The hemodynamic and metabolic changes associated with pregnancy are responsible for the higher frequency of maternal and feto‐neonatal complications reported in pregnant women with preexisting heart disease compared with pregnant women without heart disease.3, 5, 6, 7, 8 Whether these pregnancy changes affect long‐term outcomes in women with preexisting heart disease has not been systematically examined. Prior studies examining outcomes after pregnancy in women with heart disease have been limited, reporting on only small numbers of women, following for relatively short time intervals after pregnancy, or lacking comparison groups.39, 40, 41, 42 Combining patient level and administrative data allowed us to match and adjust for confounding factors and capture outcome events over a prolonged period of follow‐up.13, 15, 35, 36, 37 The high rate of occurrence of adverse cardiovascular events in women with heart disease, when they were still relatively young (age 40–50 years), highlights the significant long‐term burden of cardiovascular disease in this population. The high rates of long‐term cardiovascular events in these young women with heart disease may represent the natural history of their underlying cardiac disease. It is also possible that the hemodynamic stress of pregnancy adversely affects cardiac structure and function in women with preexisting heart disease differently than women without heart disease.43 We have reported that women with heart disease have an exaggerated increase in B‐type natriuretic peptide during pregnancy, likely as a result of ventricular distention.44 Incomplete return of cardiac structure and function back to the prepregnancy state may be a partial reason for our observation that the risk of cardiac outcome was the highest in the earlier years of follow‐up.

To our knowledge, this study was the first to examine long‐term major cardiovascular adverse events and cardiovascular risk factors in women with preexisting heart disease. Previous population studies in women without heart disease have demonstrated the relationship between obstetric complications, such as gestational hypertension, maternal placental syndrome, cesarean delivery, and congenital heart disease in the offspring,13, 15, 35, 36, 37 and subsequent long‐term cardiovascular outcomes in the mother. In our current study, even after adjusting for the above‐mentioned risk factors, women with heart disease were still more likely to develop new hypertension or diabetes mellitus than women without heart disease. Their higher long‐term atherosclerotic risk is suggested by the higher rate of myocardial infarction or stroke in the heart disease group. Pregnancy‐related hypercoagulability, inflammatory activity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia are more pronounced in women with gestational hypertension, with endothelial dysfunction thought to be the link between gestational hypertension, placental disorders, and late atherosclerotic events.13, 15, 35, 36, 37 Since pregnant women with heart disease are already at elevated risk for noncardiac pregnancy complications,8 it is possible that maternal heart disease may further elevate their propensity for hypertension or insulin resistance. While the mechanisms underlying our study findings will require further investigation, the combination of preexisting heart disease and increased risk for atherosclerotic risk factors is an unfavorable combination and points to the need for continuing postpartum surveillance and risk factor modification in this group of women.

We and others have derived and validated classification methods to predict the risk of maternal cardiovascular complications in pregnant women with heart disease.9 Our study was the first to demonstrate that previously derived pregnancy risk assessment tools to predict maternal cardiovascular complications in pregnant women with heart disease,3, 4, 14 can be expanded and used for risk stratification of long‐term cardiovascular outcomes. When applying our study results, it is important to note that CARPREG risk scores incorporate history of heart failure, arrhythmia, and stroke before the index pregnancy and is independent of the primary outcomes, which are measured after the index pregnancy. Furthermore, in calculating the risk of primary outcomes in relationship to CARPREG and WHO risk categories, we also adjusted for cardiovascular events during pregnancy. As the long‐term cardiovascular risk in low‐risk groups such as WHO class I was higher than matched comparison groups, our study findings are a reminder that “low risk” does not mean “no risk.” Our study findings simplify risk assessment for the clinician who can identify pregnancy‐related and long‐term cardiovascular risk with 1 risk assessment tool. Importantly, this ability to risk stratify long‐term risk was consistently observed with the 3 different pregnancy risk classification tools that were evaluated. In addition, the above‐mentioned risk assessment tools include the wide spectrum of maternal heart disease seen in women of childbearing age.

The strength of this study was the combined use of patient‐level and administrative data. The use of patient‐level data enabled the characterization of the pregnancy risk profile of the women with heart disease. The use of administrative healthcare databases enabled us to identify a comparable group of women without heart disease from the Ontario population, as well as determining outcomes without loss of follow‐up. By using birth records from Ontario, Canada's most populous province, we were able to identify a comparison group that was similar to the heart disease group on key parameters other than maternal heart disease. As we used validated administrative databases that captured both ambulatory encounters and hospitalization, we are able to provide a more accurate determination of the frequency of late cardiovascular outcomes. This research approach also allowed for adjustment for the effects of subsequent pregnancies on outcomes. Our study was not designed to address whether pregnancy accelerates clinical or lesion progression in women with heart disease,40, 41, 42 as it would be difficult to identify a comparable group of women with heart disease who never underwent pregnancy. A population‐based study from Canada reported that 80% of women of childbearing age with congenital heart disease have at least 1 pregnancy, with absolute number and rates of pregnancy increasing with time.2 In addition to the progressive decline in the number of women with heart disease who do not undergo pregnancy, women with heart disease who did not undergo pregnancy may differ from women with heart disease who underwent pregnancy in demographics, comorbidities, or prognosis. Our study results are applicable only to women with pregnancies that progress beyond 20 weeks and women who survived beyond the postpartum period. However, we have previously reported that 96% of pregnancies in women with heart disease progressed beyond 20 weeks.4 There were <6 maternal deaths during the index pregnancy in this study. The proportion of mortality from cardiovascular causes may be underreported, as cause of death is based on certificates of death. While we were not able to determine the role of postpregnancy care in determining outcomes, our analyses adjusted for baseline demographics and socioeconomic status. However, the generalizability of our study findings was optimized by the determination of outcomes using standardized hospital admissions and ambulatory visit databases, including a large study group with a spectrum of cardiac lesions and pregnancy risks, and conducted in women who have universal access to health care.

Conclusions and Implications for Clinical Practice

Following pregnancy, women with heart disease are at high risk for adverse long‐term cardiovascular outcomes including new hypertension or diabetes mellitus. Our findings highlight the importance of ongoing surveillance and risk factor modification in these young women after pregnancy. Current tools for cardiovascular risk assessment during pregnancy can also be used to risk stratify for long‐term cardiovascular risk after pregnancy.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported in part by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (MOP 111139), Canadian Foundation of Innovation (X0910B90), and the Tiffin Trust. Dr Siu is supported in part by the Program in Experimental Medicine, Western University Department of Medicine. Dr Silversides is supported by the Miles S. Nadal Chair in Pregnancy and Heart Disease, and Dr Lee is supported by the Ted Rogers Chair in Heart Function Outcomes. Dr Austin is supported by a Mid‐Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S7

Figures S1–S6

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted at ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information and Cancer Care Ontario. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020584. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020584.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 12.

References

- 1.ACOG practice bulletin no. 212: pregnancy and heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e320–e356. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottega N, Malhame I, Guo L, Ionescu‐Ittu R, Therrien J, Marelli A. Secular trends in pregnancy rates, delivery outcomes, and related health care utilization among women with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019;14:735–744. DOI: 10.1111/chd.12811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siu SC, Sermer M, Colman JM, Alvarez AN, Mercier L‐A, Morton BC, Kells CM, Bergin ML, Kiess MC, Marcotte F, et al. Prospective multicenter study of pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease. Circulation. 2001;104:515–521. DOI: 10.1161/hc3001.093437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silversides CK, Grewal J, Mason J, Sermer M, Kiess M, Rychel V, Wald RM, Colman JM, Siu SC. Pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease: the CARPREG II study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2419–2430. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hameed AB, Lawton ES, McCain CL, Morton CH, Mitchell C, Main EK, Foster E. Pregnancy‐related cardiovascular deaths in California: beyond peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:379.e1–379.e10. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima FV, Yang J, Xu J, Stergiopoulos K. National trends and in‐hospital outcomes in pregnant women with heart disease in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:1694–1700. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opotowsky AR, Siddiqi OK, D'Souza B, Webb GD, Fernandes SM, Landzberg MJ. Maternal cardiovascular events during childbirth among women with congenital heart disease. Heart. 2012;98:145–151. DOI: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siu SC, Colman JM, Sorensen S, Smallhorn JF, Farine D, Amankwah KS, Spears JC, Sermer M. Adverse neonatal and cardiac outcomes are more common in pregnant women with heart disease. Circulation. 2002;105:2179–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Souza RD, Silversides CK, Tomlinson GA, Siu SC. Assessing cardiac risk in pregnant women with heart disease: how risk scores are created and their role in clinical practice. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1011–1021. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MB, Walsh MN. Cardio‐obstetrics. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005417. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkayam U, Goland S, Pieper PG, Silverside CK. High‐risk cardiac disease in pregnancy: part I. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:396–410. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkayam U, Goland S, Pieper PG, Silversides CK. High‐risk cardiac disease in pregnancy: part II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:502–516. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta LS, Warnes CA, Bradley E, Burton T, Economy K, Mehran R, Safdar B, Sharma G, Wood M, Valente AM, et al. Cardiovascular considerations in caring for pregnant patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e884–e903. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Roos‐Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomström‐Lundqvist C, Cífková R, De Bonis M, Iung B, Johnson MR, Kintscher U, Kranke P, et al. 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3165–3241. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): population‐based retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366:1797–1803. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu N, Farrugia MM, Vigod SN, Urquia ML, Ray JG. Intergenerational abortion tendency between mothers and teenage daughters: a population‐based cohort study. CMAJ. 2018;190:E95–E102. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.170595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ray JG, Booth GL, Alter DA, Vermeulen MJ. Prognosis after maternal placental events and revascularization: PAMPER study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:106.e1–106.e14. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska‐Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying patients with physician‐diagnosed asthma in health administrative databases. Can Respir J. 2009;16:183–188. DOI: 10.1155/2009/963098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska‐Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying individuals with physician diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6:388–394. DOI: 10.1080/15412550903140865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guttmann A, Nakhla M, Henderson M, To T, Daneman D, Cauch‐Dudek K, Wang X, Lam K, Hux J. Validation of a health administrative data algorithm for assessing the epidemiology of diabetes in Canadian children. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11:122–128. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:512–516. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahane A, Park AL, Ray JG. Dysfunctional uterine activity in labour and premature adverse cardiac events: population‐based cohort study. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:45–51. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray JG, Park AL, Dzakpasu S, Dayan N, Deb‐Rinker P, Luo W, Joseph KS. Prevalence of severe maternal morbidity and factors associated with maternal mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e184571. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu JV, Naylor CD, Austin P. Temporal changes in the outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in Ontario, 1992–1996. CMAJ. 1999;161:1257–1261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, Cauch‐Dudek KJ, McAlister FA. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1:e18–e26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah BR, Chiu M, Amin S, Ramani M, Sadry S, Tu JV. Surname lists to identify South Asian and Chinese ethnicity from secondary data in Ontario, Canada: a validation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:42. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J. 2002;144:290–296. DOI: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipscombe LL, Hwee J, Webster L, Shah BR, Booth GL, Tu K. Identifying diabetes cases from administrative data: a population‐based validation study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:316. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-3148-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz SE, Rothwell DM, Chen Z, Tu K. Identifying cases of congestive heart failure from administrative data: a validation study using primary care patient records. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33:160–166. DOI: 10.24095/hpcdp.33.3.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu K, Nieuwlaat R, Cheng SY, Wing L, Ivers N, Atzema CL, Healey JS, Dorian P. Identifying patients with atrial fibrillation in administrative data. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:1561–1565. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen BB. The prognostic analogue of the propensity score. Biometrika. 2008;95:481–488. DOI: 10.1093/biomet/asn004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Austin PC. Statistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many‐to‐one matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1092–1097. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwq224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robson S, Hunter S, Moore M, Dunlop W. Haemodynamic changes during the puerperium: a Doppler and M‐mode echocardiographic study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;94:1028–1039. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. DOI: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auger N, Potter BJ, Bilodeau‐Bertrand M, Paradis G. Long‐term risk of cardiovascular disease in women who have had infants with heart defects. Circulation. 2018;137:2321–2331. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alonso‐Ventura V, Li Y, Pasupuleti V, Roman YM, Hernandez AV, Perez‐Lopez FR. Effects of preeclampsia and eclampsia on maternal metabolic and biochemical outcomes in later life: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Metabolism. 2020;102:154012. DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.154012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galin S, Wainstock T, Sheiner E, Landau D, Walfisch A. Elective cesarean delivery and long‐term cardiovascular morbidity in the offspring—a population‐based cohort analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:1–8. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/14767058.2020.1797668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Austin PC, Latouche A, Fine JP. A review of the use of time‐varying covariates in the Fine‐Gray subdistribution hazard competing risk regression model. Stat Med. 2020;39:103–113. DOI: 10.1002/sim.8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balint OH, Siu SC, Mason J, Grewal J, Wald R, Oechslin EN, Kovacs B, Sermer M, Colman JM, Silversides CK. Cardiac outcomes after pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Heart. 2010;96:1656–1661. DOI: 10.1136/hrt.2010.202838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grewal J, Siu SC, Ross HJ, Mason J, Balint OH, Sermer M, Colman JM, Silversides CK. Pregnancy outcomes in women with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;55:45–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guedes A, Mercier LA, Leduc L, Berube L, Marcotte F, Dore A. Impact of pregnancy on the systemic right ventricle after a Mustard operation for transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:433–437. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzemos N, Silversides CK, Colman JM, Therrien J, Webb GD, Mason J, Cocoara E, Sermer M, Siu SC. Late cardiac outcomes after pregnancy in women with congenital aortic stenosis. Am Heart J. 2009;157:474–480. DOI: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kampman MAM, Balci A, Groen H, van Dijk APJ, Roos‐Hesselink JW, van Melle JP, Sollie‐Szarynska KM, Wajon EMCJ, Mulder BJM, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Cardiac function and cardiac events 1‐year postpartum in women with congenital heart disease. Am Heart J. 2015;169:298–304. DOI: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanous D, Siu SC, Mason J, Greutmann M, Wald RM, Parker JD, Sermer M, Colman JM, Silversides CK. B‐type natriuretic peptide in pregnant women with heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1247–1253. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S7

Figures S1–S6