Abstract

Introduction:

Methamphetamine is a potent psychomotor stimulant, and methamphetamine abusers are up to three times more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease (PD) later in life. Prodromal PD may involve gut inflammation and the accumulation of toxic proteins that are transported from the enteric nervous system to the central nervous system to mediate, in part, the degeneration of dopaminergic projections. We hypothesized that self-administration of methamphetamine in rats produces a gut and brain profile that mirrors pre-motor and early-stage PD.

Methods:

Rats self-administered methamphetamine in daily 3h sessions for two weeks. Motor function was assessed before self-administration, during self-administration and throughout the 56 days of forced abstinence. Assays for pathogenic markers (tyrosine hydroxylase, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), α-synuclein) were conducted on brain and gut tissue collected at one or 56 days after cessation of methamphetamine self-administration.

Results:

Motor deficits emerged by day 14 of forced abstinence and progressively worsened up to 56 days of forced abstinence. In the pre-motor stage, we observed increased immunoreactivity for GFAP and α-synuclein within the ganglia of the myenteric plexus in the distal colon. Increased α-synuclein was also observed in the substantia nigra pars compacta. At 56 days, GFAP and α-synuclein normalized in the gut, but the accumulation of nigral α-synuclein persisted, and the dorsolateral striatum exhibited a significant loss of tyrosine hydroxylase.

Conclusion:

The pre-motor profile is consistent with gut inflammation and gut/brain α-synuclein accumulation associated with prodromal PD and the eventual development of the neurological disease.

Keywords: α-synuclein, addiction, stimulant, basal ganglia, GFAP, dopamine

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic use of the potent psychostimulant methamphetamine is associated with significant physiological and psychological deficits (Darke et al., 2008;Homer et al., 2008). Retrospective epidemiological studies revealed that individuals with a history of methamphetamine dependence are up to three times more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease (PD) than controls (Callaghan et al., 2010;Callaghan et al., 2012;Curtin et al., 2015). These reports suggest the importance of identifying pathological links between these disorders, and discovering potential biomarkers within methamphetamine abusers that predicate a vulnerability to develop PD.

Methamphetamine increases cytosolic and extracellular concentrations of monoamines (Witkin et al., 1999;Fleckenstein et al., 2007;Sulzer et al., 2005). The striatum, an area enriched with dopaminergic terminals, exhibits pathology in human methamphetamine abusers, including loss of dopamine transporters, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), dopamine, and dopamine receptors (Wilson et al., 1996;Volkow et al., 2015;Kish et al., 2017). The anatomical selectivity of methamphetamine abuse mirrors early neuropathogenesis of PD. PD is a progressive disorder, with initial loss of lateral striatum dopaminergic terminals that spreads to dopaminergic deafferentation of the entire dorsal striatal complex (Thrash et al., 2010) followed by a loss of dopaminergic cell bodies in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Transcranial sonography in methamphetamine abusers show structural abnormalities in the substantia nigra (Todd et al., 2016;Rumpf et al., 2017); such abnormalities are associated with an increased risk of developing PD (Berg et al., 2012).

Cytokine-mediated toxicity is thought to contribute to PD progression (Khandelwal et al., 2011), as evidenced by glial activation in the substantia nigra of patients with PD (McGeer et al., 1988). The neuro-immunological status of methamphetamine abusers remains uncertain (Kish et al., 2017); however, increased glial cell density has been reported for the striatum and midbrain of methamphetamine abusers (Sekine et al., 2008), and extended periods of abstinence from methamphetamine use may induce reactive astrogliosis (Kitamura et al., 2010). Neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (i.e., Lewy bodies or Lewy neurites) that contain protein components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and α-synuclein are neuropathological hallmarks of PD (e.g., (Brundin et al., 2008)). One post mortem study of overdosed methamphetamine users identified ubiquitin-positive inclusions in midbrain tissue (Quan et al., 2005); α-synuclein was not investigated. The progression of PD may involve retrograde transport of α-synuclein via vagal nerves from the gastrointestinal system to the brainstem, and subsequent trans-synaptic transport to the cortex (Braak et al., 2006;Brundin et al., 2008). Gastrointestinal α-synuclein pathology is observed in PD (Wakabayashi et al., 1990;Braak et al., 2006;Beach et al., 2010), and gut accumulation of α-synuclein is reported to occur prior to the onset of motor symptoms (Braak et al., 2006;Shannon et al., 2012). The consequences of methamphetamine abuse on gastrointestinal status have only received attention in limited human case reports (e.g., ischemic colitis) (Johnson and Berenson, 1991;Prendergast et al., 2014).

Rodent models of human methamphetamine abuse are used to describe methamphetamine-induced neuropathology. High doses of methamphetamine administered by the experimenter (i.e., non-contingent administration) result in nigrostriatal dopaminergic toxicity (see (Krasnova and Cadet, 2009)), increases in nigrostriatal α-synuclein (Fornai et al., 2005;Butler et al., 2014), and striatal glia activation (Hess et al., 1990;O’Callaghan and Miller, 1994). But these doses and the dosing patterns do not replicate the smaller doses nor injection profile of self-administered methamphetamine. It remains unclear if such pathologies would occur in more ‘physiological’ rat models of human methamphetamine use. We previously revealed in rats who self-administer methamphetamine for 14 days, that during subsequent forced abstinence a time-dependent, progressive loss of TH immunoreactivity (ir) occurs in the basal ganglia (Kousik et al., 2014a). For example, after 28 days of abstinence, there is a 20% loss of TH-ir neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. The loss of TH-ir neurons and fibers was validated by co-varying reductions in striatonigral fluorogold transport (Kousik et al., 2014a). We also demonstrated that one day after the last methamphetamine self-administration session, there was an increase in α-synuclein-ir and a decrease in TH-ir in the distal colon (Flack et al., 2017). These markers returned to baseline levels following longer withdrawal times (Flack et al., 2017). Here, we report similar changes in the distal colon, and reveal increased α-synuclein immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra pars compacta, a brain region affected in PD. Moreover, with longer times after methamphetamine exposure, we observed loss of TH in the striatum that was associated with a PD-like motor deficit. These outcomes reveal that methamphetamine self-administration results in a gut-brain profile in rats that mirrors early-stage PD.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 225–274g upon arrival were housed in pairs, handled daily, and acclimated to environmentally controlled conditions (temperature set point 22°C, humidity set 40–45%) for one week before experimentation. Rats had access to food and water ad libitum throughout the studies. To collect brain and colon tissues for assays, rats were deeply anesthetized and perfused transcardially with saline or artificial cerebrospinal fluid (Kousik et al., 2014a;Graves et al., 2015). All procedures were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, Washington DC) with protocols approved by the Rush University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Behavioral Assessments

2.2.1. Self-Administration

Procedures for catheter implants and the operant self-administration task are described in our prior reports (Kousik et al., 2014a;Graves et al., 2015). In brief, rats were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane, and catheters, constructed of silastic tubing (0.3mm × 0.64mm; Dow Corning Co., Midland, MI), were inserted into the right jugular vein and secured with sutures. Rats were allowed to recover from surgery for 5 days; catheters were flushed daily with 0.1–0.2mL 0.9% sterile saline to maintain patency. Following this recovery period, rats were trained on a lever-pressing operant task to self-administer (+)methamphetamine HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), dissolved in sterile saline. This isomer was selected as it is the form of methamphetamine preferred by methamphetamine abusers, and illicit methamphetamine distributed in the United States is in the dextro form (Li et al., 2010;Mendelson et al., 2006). The task was conducted in operant chambers (Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT) equipped with two levers, a stimulus light above each lever, and a house-light on the opposite wall. Infusions of methamphetamine were delivered by a syringe attached to an infusion pump. The concentration and dose delivered was 0.1mg/kg per 0.1mL infusion per our prior studies (Graves and Napier, 2011;Graves and Napier, 2012;Kousik et al., 2014a;Kousik et al., 2014b;Graves et al., 2015), as well as numerous studies from other laboratories (Krasnova et al., 2013;Snider et al., 2013;Miller et al., 2015;Spence et al., 2016;Winkler et al., 2018). Self-administration sessions lasted for 3h/day. Depressing the active (left) lever resulted in infusion of methamphetamine over 6s. Infusions were accompanied by illumination of the stimulus light above the active lever. Following the infusion, the house-light was illuminated for 20s to indicate a “time out” period. During this time-out, active lever presses were recorded but had no programmed consequence. Inactive (right) lever presses had no programmed consequences. Rats self-administered methamphetamine for a total of 14 consecutive days. Saline-yoked rats underwent identical handling and surgical procedures as methamphetamine self-administering rats. Lever presses by saline-yoked rats had no programmed consequences and saline infusions of 0.1mL were delivered according to the pattern of intake by a paired methamphetamine self-administering rat. This procedure maintains self-administration without producing overt withdrawal symptoms (e.g., changes in weight or grooming behavior) during abstinence.

2.2.2. Forelimb Adjusted Stepping Task

Postural instability occurs in early stages of PD, and this motor deficit is modeled in rats using the forelimb adjusted stepping task (Chang et al., 1999). We utilized this task as motor index of the TH loss in the dorsolateral striatum (DLS), the rodent homolog of the human putamen. In brief, the rear legs and one forelimb were gently restrained, and the rat was ‘dragged’ laterally on the unrestrained forelimb (0.9m/5s) in the abduction direction. The number of steps taken was counted and averaged across three trials for each forelimb. The test was conducted before the start of methamphetamine self-administration (baseline), once per week during methamphetamine self-administration, and on days 1, 14, 28 and 56 of forced abstinence.

2.3. Assays

For assessments at one day after cessation of methamphetamine, brain and colon tissue samples were taken from rats also used for prior studies on methamphetamine self-administration (Kousik et al., 2014a;Graves et al., 2015). A total of 56 rats were assayed. Tissue availaibility limited the number of assays that could be conducted for each rat. Thus, the same rats were not included in all assays. The rats represented in each treatment group were randomly selected by an individual who was blinded to the amount of meth self-administered. An additional cohort of rats (n=16) was used for the 56 day study.

Several comparisons verified that outcomes were similar between the cohorts and not influenced by the sequential nature of the testing. To illustrate, scatter plots of outcomes in the saline-yoked rats overlapped in the one and 56 day cohorts for striatal immunoblots and immunohistochemistry, nigral cell counts, and colon immunohistochemistry (S1).

2.3.1. Immunohistochemistry - Colon

Coronal sections (8μm) were obtained from paraffin-embedded distal colons. Sections were de-paraffinized, rehydrated, and exposed to 88% formic acid for 15min before citric acid antigen retrieval (pH 6.0 at 90°C for 15min). Tissue was subsequently incubated in 3% normal goat serum and 2% bovine serum albumin for 1h before overnight incubation with primary antibodies for α-synuclein (1:500, Cell Signaling) or glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:1000, Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA).

Distal colons embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound were flash-frozen; coronal sections (8μm) were cut on a cryostat. Tissue was post-fixed with acetone (−20°C for 15min), air-dried, and incubated in 3% normal goat serum and 2% bovine serum albumin for 1h before overnight incubation with primary antibody for α-synuclein (1:250, Cell Signaling) or GFAP (1:500, Wako). All tissues were washed and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200, Vector Laboratories), followed by ABC reagent (Vectastain Elite, Vector Laboratories). Stain visualization was achieved by 3,3-diaminobenzidine with and without nickel enhancement. Sections without nickel enhancement were counterstained with cuprolinic blue dye (quinolinic pthalocyanine, Polysciences Inc, Warrington, PA), as previously published (Shannon et al., 2012b). Controls included a primary omit and pre-absorption of the primary antibody with the α-synuclein peptide (Cell Signaling). No staining was observed in either control (data not shown), the latter indicating that the antibody is specific to endogenous α-synuclein.

In the distal colon, optical density of GFAP and α-synuclein-ir and area of myenteric ganglia were assessed by a treatment-blinded observer using an Olympus microscope (Olympus America, Inc.) equipped with a 20x objective connected to the Scion Image analysis system (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD). One to two colon sections were evaluated per rat. Within each colon section, all ganglia were identified and measured in triplicate. Averaged optical density of three fields outside the area of interest was used to normalize for procedural variability.

2.3.2. Immunohistochemistry - Brain

Rat brains were hemisected; the right hemisphere was immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 days and then saturated in 30% sucrose. Following saturation, coronal sections (30μm) were cut and stored in cryoprotectant at 4°C. Sections were rinsed and treated for endogenous peroxidase activity inhibition (0.1M sodium periodate in TBS) for 20min. For TH-ir and GFAP-ir, sections were subjected to citric acid antigen retrieval (pH 6.0 at 90°C for 15min) prior to endogenous peroxidase activity inhibition. Non-specific background staining was blocked with 3% normal goat serum and 2% bovine serum albumin for 1h. Sections were then incubated in primary antibody for α-synuclein (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), TH (1:10,000; Immunostar, Hudson, Wisconsin, USA) or GFAP (1:10,000; DAKO) overnight at room temperature. Sections were incubated with species appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1h followed by an avidin-biotin complex reagent (ABC Vectastatin Elite, Vector Laboratories) for 45min. The reaction was visualized using 3,3 diaminobenzidine. Primary omit sections were done as a negative control. Tissue sections immunostained with α-synuclein were counterstained for Nissl using 0.1% cresyl violet to identify cell bodies.

The number of α-synuclein positive cells was quantified in the substantia nigra pars compacta using unbiased stereological cell counting techniques. Five sections spaced 180μM apart within the substantia nigra, spanning −4.80 to −5.28mm from Bregma, were used for analysis. Section thickness was confirmed to be 25.8±0.4μM after dehydration and did not differ between groups. The optical fractionator probe was used to estimate total number of α-synuclein positive cells (Acosta et al., 2015). Briefly, the system was composed of an Olympus BX52 microscope (Olympus America Inc.), Ludl motorized stage, Stereo Investigator version 7.0 software (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT), and a Microfire CCD camera (Optronics, Goleta, CA). The substantia nigra pars compacta was outlined at 1.25x magnification. Counts of α-synuclein positive cells were completed in the left hemisphere. The counting frame size was 140μm×140μm, and the virtual grid size was 175μm×175μm. This corresponds to sampling 64% of the entire volume of the substantia nigra pars compacta. On average, 60 sites were counted per animal with error of coefficients less than 0.2. The Gundersen method for calculating the coefficient of error (CE) was used to estimate the accuracy of the optical fractionator results (West and Gundersen, 1990;Gundersen et al., 1999). The estimated total numbers of α-synuclein positive cells were used for statistical comparisons between treatments within each time point.

Optical density in the striatum for TH-ir and GFAP-ir was determined in the DLS (+1.6mm to 0.7mm from Bregma). Photomicrographs were taken at 4x magnification using an Olympus BX-UCB microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, NY) by a treatment-blinded observer. A 16mm2 field from the center of the DLS was measured. In addition, optical density of a 1mm2 field of the cortex or corpus callosum in the same section was used to determine background staining to normalize for procedural variability. The averaged background was subtracted from the average value of the striatal field for each animal. Optical densities were measured for the 3 serial sections within the DLS and averaged.

2.3.3. Immunoblotting - Brain

The striatum and substantia nigra (pars compacta and pars reticulata) were dissected from the left hemisphere and fast-frozen on dry ice. Immunoblot procedures generally followed our prior published reports (e.g., (McDaid et al., 2006;Herrold et al., 2009;Kousik et al., 2014b)). Tissue homogenates were prepared in 10vol ice-cold lysis buffer [25mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 500mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 1mM PMSF, 20mM NaF, 1x phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich), 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) and 0.1% nonidet P-40] using Dounce homogenization followed by sonication for 5s. Samples were centrifuged (14,000rpm) for 2min, and the supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976). Samples (20μg) were loaded and electrophoresed on 4–15% gradient Tris-HCl gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Non-specific binding was blocked using 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST (tris-buffered saline+Tween-20; 20mM Tris, 137mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween-20, pH 7.4), for 1h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated in primary antibodies for TH (1:7500, Millipore, Billerica, MA), α-synuclein (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), or GFAP (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology). After washing in TBST, membranes were incubated in species-appropriate secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1h at room temperature. Following washing in TBST, membranes were immersed in enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Pico, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), and exposed to HyBlot CL film (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ). Membranes were stripped [62.5mM Tris, 2% SDS, 100mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.8]) for 30min at 60°C and re-probed for GAPDH (Millipore) or actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) as a loading control. Immunoreactive band optical density was analyzed using Un-ScanIt software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Immunoblotting for TH and GFAP resulted in single bands (at 62kDa and 50kDa, respectively). Quantification for all proteins was accomplished by dividing the optical density value by that of the loading control (actin or GAPDH). Results from methamphetamine self-administering rats were normalized to saline-yoked rats within each gel. Samples were run in at least duplicate and averaged across runs.

2.4. Statistics

A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the average methamphetamine intake for the last three days of self-administration to verify there was no difference across studies. In the 56 day study, a one-tailed paired t-test was used to acquisition of the operant task following the second self-administration session. Postural instability data were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures; a post hoc Bonferroni’s test was used to determine between-group differences at each time point. Immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry data were analyzed between groups within each time point using a one-tailed Student’s t-test. Significance was set at p<0.05. All data are presented as mean+SEM.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Methamphetamine self-administration

Self-administration data obtained from rats whose tissues were collected one day after the last operant session are described in two of our previous reports (Kousik et al., 2014a;Graves et al., 2015). Similar behavioral results were obtained in the current study for the rats killed at 56 days of forced abstininence. In all three studies, the rats rapidly acquired the operant task and achieved increased responding on the reinforced lever within a few days. To illustrate, the current study cohort exhibited a significant preference for the reinforced lever after the second self-administration session (active lever: 19.6±4.2 presses, inactive lever: 8.9±1.9 presses; t7=3.9, p=0.003). Moreover, the average intake for the last three days of self-administration was not statistically different among the three studies (in mg/kg): 1.58±0.11 (Kousik et al., 2014a), 1.88± 0.25 (Graves et al., 2015), and 1.45±0.37 (56d rats, current study) (F(2,35)=0.59, p=0.56).

3.2. Postural Instability

No motor impairment was observed during methamphetamine self-administration (Fig. 1). During forced abstinence from methamphetamine, postural instability emerged by day 14. There was a significant main effect of treatment (F(1,70)=13.03, p=0.003) and time (F(5,70)=22.49, p<0.0001), and significant treatment x time interaction (F(5,70)=3.54, p=0.007). Post hoc comparisons revealed specific time-related differences between methamphetamine-treated rats and saline-yoked controls at 14, 28 and 56 days of forced abstinence. These data align with our previously published report wherein a significant loss of TH was observed in the DLS beginning at 14 days of forced abstinence from methamphetamine (Kousik et al., 2014a). Based on these motor results, we considered outcomes prior to forced abstinence day 14 to reflect a “premotor” stage and those subsequent to forced abstinence day 14 to reflect an “early PD-like” stage. Accordingly, colon and brain tissues harvested during extremes of these two stages (i.e., one and 56 days after the methamphetamine operant task) were used to assess PD-like markers.

Figure 1. Methamphetamine self-administering rats exhibited postural instability following forced abstinence.

Rats were tested for postural instability/akinesia using the forelimb adjusted stepping test prior to methamphetamine exposure as well as during self-administration and forced abstinence. There was no motor deficit observed during the prior to self-administration (baseline, BL) during the 14 days of self-administration (SA14) or one day after the last exposure to methamphetamine. However, following 14 days, 28 days and 56 days of forced abstinence, rats that self-administered methamphetamine showed postural instability compared to saline-yoked controls. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test, ** p<0.01.

3.3. Pre-Motor Stage

In the colon, myenteric ganglia contained GFAP-ir in saline-yoked rats; however, the intensity of staining was enhanced in rats that self-administered methamphetamine (Fig. 2A, top). Punctate α-synuclein-ir was observed in the myenteric plexus ganglia of the saline-yoked rats; cell bodies were essentially devoid of staining. In contrast, α-synuclein-ir was robust in ganglia from rats that self-administered methamphetamine, including intense staining within the cell bodies of the ganglia (Fig. 2A, bottom). Quantification of optical density verified that methamphetamine rats had significantly greater GFAP-ir (t(14)=4.44, p=0.003) and α-synuclein-ir (t(13)=6.18, p<0.0001) compared to saline-yoked rats (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and α- synuclein (α-syn) in the myenteric ganglia of the distal colon one day after methamphetamine self-administration (Meth SA).

(A) Representative microphotographs of GFAP-ir and α-syn-ir, enhanced with nickel, showing enteric glial cells in the distal colon. High power (120x; scale bar=12.5μm) images to depict myenteric ganglia between the longitudinal and inner circular muscle layers in a saline-yoked rat and Meth SA rat. Though GFAP-ir was present in saline-yoked controls, Meth SA rats displayed more robust GFAP-ir. Punctate α-syn-ir was present in saline-yoked controls, but cell bodies were largely devoid of staining. In contrast, Meth SA rats displayed robust α-syn-ir in the myenteric ganglia cell bodies. (B) Optical density quantification of GFAP-ir and α-syn-ir in myenteric ganglia revealed significantly greater protein expression following methamphetamine exposure as compared to saline-yoked controls. Student’s t-test, ** p<0.01.

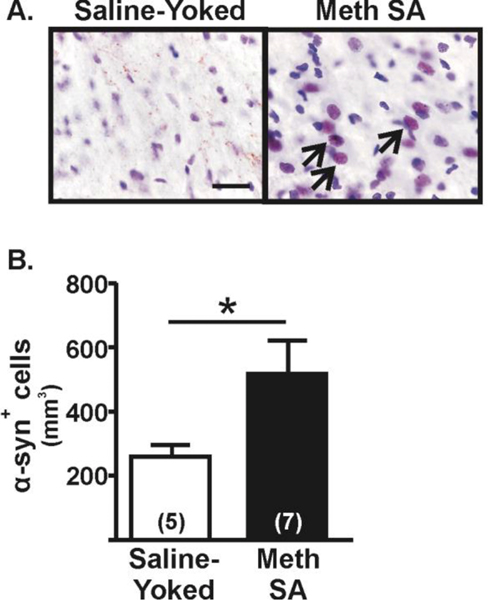

In the substantia nigra, immunoblotting showed no difference in the levels of α-synuclein between rats that self-administered methamphetamine and saline-yoked controls (114.8±10.7 vs. 101.8 ±7.1, respectively; t(14)=1.04, p=0.14). However, as the nigral tissue contained both the pars compacta and pars reticulata subregions, we subsequently conducted immunohistochemical assessments of α-synuclein-ir in the pars compacta to determine changes in the dopamine cell body region. In the pars compacta of saline-yoked rats, α-synuclein-ir was punctate; very few cell bodies contained positive staining (Fig. 3A), whereas in the pars compacta from rats that selfadministered methamphetamine, numerous cell bodies contained α-synuclein-ir (counterstained with cresyl violet to indicate soma). Quantification of the number of cells containing α-synuclein-ir revealed an increase in the number of stained cell bodies in the rats that self-administered methamphetamine compared to saline-yoked controls (t(10)=2.01, p=0.04; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. α-Synuclein (α-syn) in the substantia nigra pars compacta one day after methamphetamine self-administration (Meth SA).

(A) Immunohistochemical assessment of α-syn staining in cells of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc). Representative microphotographs of α-syn-ir (brown) within cells (black arrows). Sections were counter-stained with nissl to identify cells (100X, scale bar = 12.5μm). (B) Stereological quantification of α-syn+ cells revealed a significant increase in Meth SA rats compared to saline-yoked controls. Student’s t-test, *p<0.05.

In the striatum, immunoblotting revealed no differences in TH (saline-yoked: 100.7±3.0, methamphetamine: 100.9±5.7; t(12)=0.19, p=0.49) or GFAP (saline-yoked: 100.0±4.7, methamphetamine: 104.4±2.8; t(14)=0.83, p=0.21) between treatment groups. To determine if changes in these proteins could be detected within a specific, functionally relevant subregion, we conducted immunohistochemical assessments of TH and GFAP in the DLS (Fig. 4A). Similar to prior immunoblot results, there was no difference in TH-ir (t(6)=0.67, p=0.26) or GFAP (t(6)=0.96, p=0.19) between treatment groups within the DLS subfield (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the striatum one day after methamphetamine self-administration (Meth SA).

(A) Representative photomicrographs of TH and GFAP immunohistochemistry in the dorsolateral striatum (DLS) are illustrated (2X, scale bar = 1mm). The black box indicates the area of the DLS that was assessed for optical density. (B) Quantification of TH and GFAP optical density in the DLS revealed no change compared saline-yoked controls. Student’s t-test; p>0.05.

3.4. Early PD-Like Stage

Following protracted abstinence from methamphetamine, colon GFAP (t(13)=0.63, p=0.27) and α-synuclein-ir (t(13)=0.40, p=0.70) were at control levels (Fig. 5A&B). In the substantia nigra pars compacta there was a persistent increase in the number of α-synuclein stained cell bodies compared to saline-yoked rats (t(13)=3.00,p=0.006; Fig. 6A&B). Saline-yoked controls exhibited some punctate α-synuclein-ir in the substantia nigra pars compacta.

Figure 5. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and α-synuclein (α-syn) in the myenteric ganglia of the distal colon following 56 days of forced abstinence from methamphetamine.

(A) Representative microphotographs of GFAP-ir and α-syn-ir, enhanced with nickel, showing enteric glial cells in the distal colon. High power (120x; scale bar=12.5μm) images to depict myenteric ganglia between the longitudinal and inner circular muscle layers in saline-yoked rat and methamphetamine self-administering (Meth SA) rat. Rats exhibited similar GFAP and α-syn immunostaining as saline-yoked controls. (B) Quantification of GFAP and α-syn optical density in myenteric ganglia revealed no methamphetamine-induced changes. Student’s t-test; p>0.05.

Figure 6. α-Synuclein (α-syn) expression in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) following 56 days of forced abstinence from methamphetamine self-administration (Meth SA).

(A) Representative microphotographs of α-syn-ir (brown) within cells (indicated by black arrows) in the SNpc. Sections were counter stained with nissl to identify cells (100X, scale bar = 12.5μm). (B) Stereological counts of α-syn within the SNpc revealed an increase in the number of α-syn+ cells in Meth SA rats compared with saline-yoked controls. Student’s t-test, ** p<0.01.

Immunoblotting revealed no differences in striatal levels of TH (saline-yoked: 99.4±2.1, methamphetamine: 99.9±5.0; t(14)=0.09, p=0.47) or GFAP (saline-yoked: 99.6±4.8, methamphetamine: 109.5±3.6; t(14)=1.6, p=0.06) between treatment groups. The DLS exhibited decreased TH-ir in rats that self-administered methamphetamine (t(14)=2.52, p=0.01) but no evidence of astrogliosis (t(12)=1.72, p=0.06; Fig. 7A&B). This is line with a previous study in our laboratory showing reduced levels of TH in the striatum at extended forced abstinence periods from methamphetamine (Kousik et al 2014).

Figure 7. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the striatum following 56 days of forced abstinence from methamphetamine self-administration (Meth SA).

(A) Representative photomicrographs of TH-ir and GFAP-ir in the dorsolateral striatum (DLS) (2X, scale bar = 1mm). The black box indicates the area of the DLS that was assessed for optical density. (B) Quantification of optical density revealed a robust loss of TH-ir in the DLS of rats with a history of Meth SA. GFAP-ir was not altered. Student’s t-test, ** p<0.01.

4. DISCUSSION

Methamphetamine abuse as a risk factor for PD has been widely debated ((Volkow et al., 2015), for reviews, see (Kish, 2014;Lappin et al., 2018)). Two large independent retrospective studies provide compelling evidence that methamphetamine-abusing individuals exhibit a significantly higher risk for developing PD than non-abusing individuals, or those with a history of cocaine abuse (Callaghan et al., 2012;Curtin et al., 2015). The present study supports the hypothesis that methamphetamine abuse increases the risk for developing PD by identifying biomarkers associated with pre-motor and early-stage PD in the brain and colon of rats that self-administered relatively low doses of methamphetamine.

We observed that astrogliosis occurred in the distal colon of methamphetamine-exposed rats, i.e., the glial marker GFAP was increased in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus. Glial cells, specifically microglia and astrocytes, are important in initiating innate immune responses in the colon and brain, and these cells interact with infiltrating leukocytes that promote inflammation (Morale et al., 2006). In the brain, aberrant glial activation, and the subsequent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, aid in the aggregation of α-synuclein protein in the substantia nigra to form Lewy bodies (Brundin et al., 2008;Farooqui and Farooqui, 2011), contributing to neuronal degeneration. This process may be mimicked in the gut, i.e., upregulation of colon glia following methamphetamine self-administration may occur in response to increased α-synuclein burden in colon ganglia. Furthermore, reactive gliosis may promote α-synuclein accumulation in colon ganglia (Clairembault et al., 2015) leading to aggregation. Accumulation of α-synuclein within the colon submucosa is evident in subjects prior to the classic motor manifestations of PD (Lebouvier et al., 2010;Shannon et al., 2012). It would be of interest to determine if α-synuclein aggregation forms in the colon of rats that self-administer methamphetamine following protracted periods of forced abstinence. Gastrointestinal dysfunction is prevalent in PD patients prior to the emergence of motor symptoms (Cersosimo et al., 2013), and case reports suggest that intestinal ischemia may be a complication of methamphetamine abuse (Johnson and Berenson, 1991;Prendergast et al., 2014). The status of gut health in methamphetamine-abusing humans remains unclear. This knowledge gap is particularly relevant as the current data indicate that gut pathology may be a potential risk factor for developing PD.

Mechanisms that underlie a progression of pathology from the gastrointestinal system to the brain remain unclear. Braak and colleagues postulated that PD pathology may enter the central nervous system via retrograde transport from the gut, and then spread rostrally through the brain (Braak et al., 2003;Braak et al., 2006). We observed increases in α-synuclein-ir in the midbrain, without changes in the striatum at the pre-motor stage, suggesting that the consequences of methamphetamine use may mimic the progression pattern observed in PD. The progression of pathology proposed by Braak may be relevant as principal neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta are sensitive to L-type Ca2+ channel-dependent mitochondrial oxidant stress, which may attribute to their selective vulnerability in PD (Goldberg et al., 2012;Guzman et al., 2010;Sanchez-Padilla et al., 2014). Methamphetamine increases mitochondrial oxidant stress in substantia nigra pars compacta axons via monoamine oxidase metabolism of cytosolic dopamine (Graves et al., 2020). This would provide a second source of mitochondrial oxidant stress resulting from methamphetamine administration that could contribute to degeneration in vulnerable neurons. The colon may also exhibit similar oxidative stress vulnerabilities due to high metabolic needs to support continuous peristaltic contractions throughout life. Indeed, a transgenic mouse model of PD reported extensive enteric pathology, including α-synuclein aggregation, even in the absence of α-synuclein aggregation in the central nervous system (Kuo et al., 2010).

PD also involves a progressive retrograde neurodegeneration from striatal dopaminergic terminals to substantia nigra cell bodies, and robust reductions in various markers for these dopaminergic projections are recapitulated in rodent and non-human primate models of PD (Blandini, 2013). Reductions in dopaminergic markers (e.g., TH) are identified in non-human primates and rats following experimenter-administered, repeated high-doses of methamphetamine (Woolverton et al., 1989;Reichel et al., 2012). In methamphetamine self-administration paradigms wherein rats self-titrate doses of drug over a longer time period, reductions in protein levels are seen for striatal TH and dopamine transporter after 14 days of forced abstinence ((Krasnova et al., 2010;Kousik et al., 2014a), but see (Schwendt et al., 2009) and references therein). Such effects are not obtained one day after the last exposure to methamphetamine (Kousik et al., 2014a). In the present study, we did not observe statistical differences in DLS TH expression between methamphetamine self-administering rats and saline-yoked controls one day following cessation of self-administration. However, we did observe a reduction in TH at 56 days of forced abstinence, a time when motor deficits emerged in methamphetamine-treated rats. Thus, while acute high doses of methamphetamine produce striatal dopaminergic damage rapidly, self-administration does not produce an immediate dopaminergic pathology; however, with protracted abstinence from methamphetamine, the biological consequences emerge (Kousik et al., 2014a). Our postural instability data indicates that motor deficits induced by methamphetamine self-administration parallel the time-dependent loss of TH. This progressive loss of TH-ir may be initiated by vasoconstriction-induced hypoxia in the striatum. We previously demonstrated that in the pre-motor stage, HIF1α, an oxygen-dependent transcription factor that is a marker of hypoxic injury, is upregulated in the striatum (Kousik et al., 2011). Additionally, striatal vascular volume and vessel diameter are significantly reduced through 28 days of forced abstinence from methamphetamine self-administration (Kousik et al., 2014b).

α-Synuclein is a protein component of Lewy bodies identified in surviving neurons in PD, and this pathological profile is a diagnostic hallmark of the disease. We observed that α-synuclein-ir was increased in the substantia nigra pars compacta of methamphetamine self-administering rats during both the pre-motor and early PD-like stages, similar to a previous report using acute, high doses of methamphetamine in a binge regimen in mice (Fornai et al., 2005). Our observations of α-synuclein accumulation in midbrain region in the pre-motor stage, without changes in striatal TH or GFAP, supports the prevailing concept that α-synuclein accumulation precedes nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration (More et al., 2013;Sekiyama et al., 2012). Increases in α-synuclein neuronal burden may trigger inflammation and gliosis and ultimately neuronal degeneration (Sekiyama et al., 2012). The status of α-synuclein in brains of human methamphetamine abusers remains unknown, but elevated α-synuclein levels are reported for midbrain dopaminergic neurons in post mortem brains of cocaine-abusing humans (Mash et al., 2003). As a history of cocaine use does not appear to increase the risk for PD development (Callaghan et al., 2012;Curtin et al., 2015), studies directly comparing the effects of cocaine and methamphetamine on human and rat brain indices of PD would be extremely informative.

Neuroinflammation is one of multiple events that contribute to dopaminergic terminal degeneration by methamphetamine, and reactive astrogliosis is reported to be a consequence of neurotoxicity induced by high doses of methamphetamine (for reviews, see (Krasnova and Cadet, 2009)). While increases in striatal GFAP were reported for rats allowed to self-administer methamphetamine in 15hr sessions for 8 days (Krasnova et al., 2010), we observed no change in striatal GFAP expression one or 56 days after 3hr sessions for 14 days, in agreement with other reports using more moderate self-administration protocols (Schwendt et al., 2009;McFadden et al., 2012). The human gliosis data are also unclear. A recent study using post mortem tissue from human methamphetamine abusers revealed no evidence of overt striatal gliosis, e.g., GFAP levels, but there is evidence that an “astrocytic disturbance” (e.g., increased levels of GFAP fragments) had occurred (Tong et al., 2014). Extended periods of abstinence from methamphetamine binging by humans may induce reactive astrogliosis (Kitamura et al., 2010). Gliosis may not be initiated until neuronal burden and accumulation of α-synuclein has overextended neuronal capacities in its removal, recruiting and activating brain glia cells (Sekiyama et al., 2012). Though initial glial activation may serve as a protective mechanism, neuroinflammation may become aberrantly activated as α-synuclein accumulates in both neurons and glial cells leading to neurodegeneration. Thus, the lack of gliosis and the accumulation of α-synuclein in neuronal cell bodies in the brains of methamphetamine self-administering rats are in line with early-stage PD-like changes in vulnerable brain regions.

A potential shortcoming of this study is the sequential testing of the one and 56 day cohorts. Despite validation that biochemical outcomes in the control groups were similar for both cohorts, future studies could involve cross-sectional testing wherein each assessment time frame would be represented in each cohort. Moreover, it will be of interest to ascertain if the brain, gut and motor pathology continues to progress past the 56 days tested here, or if the pathological profile plateaus.

In summary, this study revealed that doses of methamphetamine that were maintained by self-administration were sufficient to induce changes in PD-like markers in the colon and brain. In the pre-motor stage, α-synuclein accumulated in the distal colon and midbrain areas without overt changes in nigrostriatal TH or GFAP. This pattern likely represents a prodromal trajectory for PD, and therefore may provide a biological basis for clinical observations that methamphetamine abusing individuals are vulnerable to developing PD. In the early PD-like stage, colon α-synuclein normalized, while there was a persistent increase in midbrain α-synuclein and a corresponding loss of DLS TH and motor deficit. Future studies are needed to determine if α-synuclein accumulation progresses to aggregation during forced abstinence from methamphetamine. Moreover, as α-synuclein in the distal colon may be an early identifier for increased risk of developing PD, colon biopsies prior to emergence of motor deficits may provide a useful clinical procedure for identification of PD disease biomarkers in high-risk groups, like methamphetamine-abusing individuals.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Methamphetamine self-administration in rats captures a progressive PD-like profile

In the pre-motor stage, GFAP and α-synuclein are increased in the colon

In the early PD-like stage, TH is decreased in the striatum

Accumulation of α-synuclein in the substantia nigra occurs in both stages

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by NIH R21 ES025920 (TCN and ALP), F31 DA024923 (SMG and TCN), R01 DA042737 (BKY) and the Center for Compulsive Behavior and Addiction at Rush University Medical Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

TCN is a consultant for Global Institutes for Addiction (Miami, FL) and has provided expert testimony for Rochon/Genova LLP (Toronto, ON). SMK is an employee of Abbvie and holds stock in that company. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Acosta SA, Tajiri N, de lP I, Bastawrous M, Sanberg PR, Kaneko Y, Borlongan CV (2015) Alpha-synuclein as a pathological link between chronic traumatic brain injury and Parkinson’s disease. J Cell Physiol 230:1024–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Vedders L, Lue L, White Iii CL, Akiyama H, Caviness JN, Shill HA, Sabbagh MN, Walker DG (2010) Multi-organ distribution of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathol 119:689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg D, Marek K, Ross GW, Poewe W (2012) Defining at-risk populations for Parkinson’s disease: lessons from ongoing studies. Mov Disord 27:656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandini F (2013) Neural and immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 8:189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, de Vos RA, Bohl J, Del TK (2006) Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci Lett 396:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del TK, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E (2003) Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24:197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundin P, Li JY, Holton JL, Lindvall O, Revesz T (2008) Research in motion: the enigma of Parkinson’s disease pathology spread. Nat Rev Neurosci 9:741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler B, Gamble-George J, Prins P, North A, Clarke JT, Khoshbouei H (2014) Chronic Methamphetamine Increases Alpha-Synuclein Protein Levels in the Striatum and Hippocampus but not in the Cortex of Juvenile Mice. J Addict Prev 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Cunningham JK, Sajeev G, Kish SJ (2010) Incidence of Parkinson’s disease among hospital patients with methamphetamine-use disorders. Mov Disord. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Cunningham JK, Sykes J, Kish SJ (2012) Increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in individuals hospitalized with conditions related to the use of methamphetamine or other amphetamine-type drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend 120:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cersosimo MG, Raina GB, Pecci C, Pellene A, Calandra CR, Gutierrez C, Micheli FE, Benarroch EE (2013) Gastrointestinal manifestations in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence and occurrence before motor symptoms. J Neurol 260:1332–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JW, Wachtel SR, Young D, Kang UJ (1999) Biochemical and anatomical characterization of forepaw adjusting steps in rat models of Parkinson’s disease: studies on medial forebrain bundle and striatal lesions. Neuroscience 88:617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clairembault T, Leclair-Visonneau L, Neunlist M, Derkinderen P (2015) Enteric glial cells: new players in Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord 30:494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin K, Fleckenstein AE, Robison RJ, Crookston MJ, Smith KR, Hanson GR (2015) Methamphetamine/amphetamine abuse and risk of Parkinson’s disease in Utah: a population-based assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend 146:30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J (2008) Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev 27:253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqui T, Farooqui AA (2011) Lipid-mediated oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis 2011:247467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack A, Persons AL, Kousik SM, Celeste NT, Moszczynska A (2017) Self-administration of methamphetamine alters gut biomarkers of toxicity. Eur J Neurosci 46:1918–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, Gibb JW, Hanson GR (2007) New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:681–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornai F, Lenzi P, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, di Poggio AB, Natale G, Busceti CL, Biagioni F, Giusiani M, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A (2005) Occurrence of neuronal inclusions combined with increased nigral expression of alpha-synuclein within dopaminergic neurons following treatment with amphetamine derivatives in mice. Brain Res Bull 65:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JA, Guzman JN, Estep CM, Ilijic E, Kondapalli J, Sanchez-Padilla J, Surmeier DJ (2012) Calcium entry induces mitochondrial oxidant stress in vagal neurons at risk in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci 15:1414–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves SM, Clark MJ, Traynor JR, Hu XT, Napier TC (2015) Nucleus accumbens shell excitability is decreased by methamphetamine self-administration and increased by 5-HT receptor inverse agonism and agonism. Neuropharmacology 89C:113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves SM, Napier TC (2011) Mirtazapine alters cue-associated methamphetamine seeking in rats. Biol Psychiatry 69:275–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves SM, Napier TC (2012) SB 206553, a putative 5-HT2C inverse agonist, attenuates methamphetamine-seeking in rats. BMC Neurosci 13:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves SM, Xie Z, Stout KA, Zampese E, Burbulla LF, Shih JC, Kondapalli J, Patriarchi T, Tian L, Brichta L, Greengard P, Krainc D, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ (2020) Author Correction: Dopamine metabolism by a monoamine oxidase mitochondrial shuttle activates the electron transport chain. Nat Neurosci 23:293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB, Kieu K, Nielsen J (1999) The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology--reconsidered. J Microsc 193:199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Wokosin D, Kondapalli J, Ilijic E, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ (2010) Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature 468:696–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrold AA, Shen F, Graham MP, Harper LK, Specio SE, Tedford CE, Napier TC (2009) Mirtazapine treatment after conditioning with methamphetamine alters subsequent expression of place preference. Drug Alcohol Depend 99:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess A, Desiderio C, McAuliffe WG (1990) Acute neuropathological changes in the caudate nucleus caused by MPTP and methamphetamine: Immunohistochemical studies. J Neurocytol 19:338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer BD, Solomon TM, Moeller RW, Mascia A, DeRaleau L, Halkitis PN (2008) Methamphetamine abuse and impairment of social functioning: a review of the underlying neurophysiological causes and behavioral implications. Psychol Bull 134:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TD, Berenson MM (1991) Methamphetamine-induced ischemic colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 13:687–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal PJ, Herman AM, Moussa CE (2011) Inflammation in the early stages of neurodegenerative pathology. J Neuroimmunol 238:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ (2014) The pathology of methamphetamine use in the human brain. In: The Effects of Drug Abuse on the Human Nervous System (Madras B, Kuhar M, eds), pp 203–298. Oxford: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ, Boileau I, Callaghan RC, Tong J (2017) Brain dopamine neurone ‘damage’: methamphetamine users vs. Parkinson’s disease - a critical assessment of the evidence. Eur J Neurosci 45:58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura O, Takeichi T, Wang EL, Tokunaga I, Ishigami A, Kubo S (2010) Microglial and astrocytic changes in the striatum of methamphetamine abusers. Leg Med (Tokyo ) 12:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousik SM, Carvey PM, Napier TC (2014a) Methamphetamine self-administration results in persistent dopaminergic pathology: implications for Parkinson’s disease risk and reward-seeking. Eur J Neurosci 40:2707–2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousik SM, Graves SM, Napier TC, Zhao C, Carvey PM (2011) Methamphetamine-induced vascular changes lead to striatal hypoxia and dopamine reduction. Neuroreport 22:923–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousik SM, Napier TC, Ross RD, Sumner DR, Carvey PM (2014b) Dopamine receptors and the persistent neurovascular dysregulation induced by methamphetamine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 351:432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (2009) Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain Res Rev 60:379–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Chiflikyan M, Justinova Z, McCoy MT, Ladenheim B, Jayanthi S, Quintero C, Brannock C, Barnes C, Adair JE, Lehrmann E, Kobeissy FH, Gold MS, Becker KG, Goldberg SR, Cadet JL (2013) CREB Phosphorylation Regulates Striatal Transcriptional Responses in the Self-administration Model of Methamphetamine Addiction in the Rat. Neurobiol Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Justinova Z, Ladenheim B, Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Barnes C, Warner JE, Goldberg SR, Cadet JL (2010) Methamphetamine self-administration is associated with persistent biochemical alterations in striatal and cortical dopaminergic terminals in the rat. PLoS ONE 5:e8790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YM, Li Z, Jiao Y, Gaborit N, Pani AK, Orrison BM, Bruneau BG, Giasson BI, Smeyne RJ, Gershon MD, Nussbaum RL (2010) Extensive enteric nervous system abnormalities in mice transgenic for artificial chromosomes containing Parkinson disease-associated alpha-synuclein gene mutations precede central nervous system changes. Hum Mol Genet 19:1633–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappin JM, Darke S, Farrell M (2018) Methamphetamine use and future risk for Parkinson’s disease: Evidence and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Depend 187:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebouvier T, Tasselli M, Paillusson S, Pouclet H, Neunlist M, Derkinderen P (2010) Biopsable neural tissues: toward new biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease? Front Psychiatry 1:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Lopez JC, Galloway GP, Baggott MJ, Everhart T, Mendelson J (2010) Estimating the intake of abused methamphetamines using experimenter-administered deuterium labeled Rmethamphetamine: selection of the R-methamphetamine dose. Ther Drug Monit 32:504–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash DC, Ouyang Q, Pablo J, Basile M, Izenwasser S, Lieberman A, Perrin RJ (2003) Cocaine abusers have an overexpression of alpha-synuclein in dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 23:2564–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaid J, Graham MP, Napier TC (2006) Methamphetamine-induced sensitization differentially alters pCREB and ΔFosB throughtout the limbic circuit of the mammalian brain. Molecular Pharmacology 70:2064–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden LM, Hadlock GC, Allen SC, Vieira-Brock PL, Stout KA, Ellis JD, Hoonakker AJ, Andrenyak DM, Nielsen SM, Wilkins DG, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE (2012) Methamphetamine self-administration causes persistent striatal dopaminergic alterations and mitigates the deficits caused by a subsequent methamphetamine exposure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340:295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, Itagaki S, Boyes BE, McGeer EG (1988) Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 38:1285–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson J, Uemura N, Harris D, Nath RP, Fernandez E, Jacob P III, Everhart ET, Jones RT (2006) Human pharmacology of the methamphetamine stereoisomers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 80:403–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ML, Aarde SM, Moreno AY, Creehan KM, Janda KD, Taffe MA (2015) Effects of active anti-methamphetamine vaccination on intravenous self-administration in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 153:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morale MC, Serra PA, L’Episcopo F, Tirolo C, Caniglia S, Testa N, Gennuso F, Giaquinta G, Rocchitta G, Desole MS, Miele E, Marchetti B (2006) Estrogen, neuroinflammation and neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease: glia dictates resistance versus vulnerability to neurodegeneration. Neuroscience 138:869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More SV, Kumar H, Kim IS, Song SY, Choi DK (2013) Cellular and molecular mediators of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Mediators Inflamm 2013:952375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan JP, Miller DB (1994) Neurotoxicity profiles of substituted amphetamines in the C57BL/6J mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 270:741–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast C, Hassanein AH, Bansal V, Kobayashi L (2014) Shock with intestinal ischemia: a rare complication of methamphetamine use. Am Surg 80:101–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan L, Ishikawa T, Michiue T, Li DR, Zhao D, Oritani S, Zhu BL, Maeda H (2005) Ubiquitin-immunoreactive structures in the midbrain of methamphetamine abusers. Leg Med (Tokyo ) 7:144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Ramsey LA, Schwendt M, McGinty JF, See RE (2012) Methamphetamine-induced changes in the object recognition memory circuit. Neuropharmacology 62:1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf JJ, Albers J, Fricke C, Mueller W, Classen J (2017) Structural abnormality of substantia nigra induced by methamphetamine abuse. Mov Disord. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Padilla J, Guzman JN, Ilijic E, Kondapalli J, Galtieri DJ, Yang B, Schieber S, Oertel W, Wokosin D, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ (2014) Mitochondrial oxidant stress in locus coeruleus is regulated by activity and nitric oxide synthase. Nat Neurosci 17:832–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendt M, Rocha A, See RE, Pacchioni AM, McGinty JF, Kalivas PW (2009) Extended methamphetamine self-administration in rats results in a selective reduction of dopamine transporter levels in the prefrontal cortex and dorsal striatum not accompanied by marked monoaminergic depletion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331:555–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Sugihara G, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Suda S, Suzuki K, Kawai M, Takebayashi K, Yamamoto S, Matsuzaki H, Ueki T, Mori N, Gold MS, Cadet JL (2008) Methamphetamine causes microglial activation in the brains of human abusers. J Neurosci 28:5756–5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama K, Sugama S, Fujita M, Sekigawa A, Takamatsu Y, Waragai M, Takenouchi T, Hashimoto M (2012) Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders: A Lesson from Genetically Manipulated Mouse Models of alpha-Synucleinopathies. Parkinsons Dis 2012:271732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon KM, Keshavarzian A, Dodiya HB, Jakate S, Kordower JH (2012) Is alpha-synuclein in the colon a biomarker for premotor Parkinson’s disease? Evidence from 3 cases. Mov Disord 27:716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider SE, Hendrick ES, Beardsley PM (2013) Glial cell modulators attenuate methamphetamine self-administration in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 701:124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence AL, Guerin GF, Goeders NE (2016) The differential effects of alprazolam and oxazepam on methamphetamine self-administration in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 166:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A (2005) Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol 75:406–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrash B, Karuppagounder SS, Uthayathas S, Suppiramaniam V, Dhanasekaran M (2010) Neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine. Neurochem Res 35:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd G, Pearson-Dennett V, Wilcox RA, Chau MT, Thoirs K, Thewlis D, Vogel AP, White JM (2016) Adults with a history of illicit amphetamine use exhibit abnormal substantia nigra morphology and parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 25:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J, Fitzmaurice P, Furukawa Y, Schmunk GA, Wickham DJ, Ang LC, Sherwin A, McCluskey T, Boileau I, Kish SJ (2014) Is brain gliosis a characteristic of chronic methamphetamine use in the human? Neurobiol Dis 67:107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Smith L, Fowler JS, Telang F, Logan J, Tomasi D (2015) Recovery of dopamine transporters with methamphetamine detoxification is not linked to changes in dopamine release. Neuroimage 121:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Ohama E, Ikuta F (1990) Parkinson’s disease: an immunohistochemical study of Lewy body-containing neurons in the enteric nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 79:581–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Gundersen HJ (1990) Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol 296:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Kalasinsky KS, Levey AI, Bergeron C, Reiber G, Anthony RM, Schmunk GA, Shannak K, Haycock JW, Kish SJ (1996) Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic methamphetamine users. Nature Med 2:699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler MC, Greager EM, Stafford J, Bachtell RK (2018) Methamphetamine self-administration reduces alcohol consumption and preference in alcohol-preferring P rats. Addict Biol 23:90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin JM, Savtchenko N, Mashkovsky M, Beekman M, Munzar P, Gasior M, Goldberg SR, Ungard JT, Kim J, Shippenberg T, Chefer V (1999) Behavioral, toxic, and neurochemical effects of sydnocarb, a novel psychomotor stimulant: comparisons with methamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 288:1298–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Ricaurte GA, Forno LS, Seiden LS (1989) Long-term effects of chronic methamphetamine administration in rhesus monkeys. Brain Res 486:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.