Abstract

Objectives:

Residential long-term care (LTC) facilities may be key settings for the prevention of suicide among older adults; however, little is known about the relationship between statewide policies determining characteristics of LTC facilities and suicide mortality. The primary goal of this study was to evaluate the association between state policies regarding availability, regulation, and cost of LTC and suicide mortality among adults aged 55 and older in the US over a 5-year period.

Design:

Longitudinal ecological study

Setting and Participants:

LTC residents from 16 states reporting mortality data to the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) from 2010 – 2015.

Methods:

We linked suicide data from the National Violent Death Reporting System and data sources on LTC services and regulations for 16 states. We applied a natural language processing algorithm to identify suicide deaths related to LTC. We used fixed effect regression models to assess whether state variation in LTC characteristics is related to variation in the rate of suicide (both overall and related to LTC) among older adults.

Results:

There were 25,040 suicides among those aged 55 and older reported to the NVDRS during the study period; 382 suicides were determined to be associated with LTC in some manner. After adjusting for state-level characteristics, greater average nursing home capacity was significantly associated with increase in the cumulative incidence of suicide related to LTC (β=0.087, SE=0.026, p<.01), but not overall suicide incidence. Neither cost nor regulation measures were significantly associated with state-level LTC-related suicide incidence.

Conclusions and Implications:

State-level variations in LTC facility capacity are related to variation in LTC-related suicide incidence among older adults. Given the challenges of preventing suicide among older adults through facility- or individual-level interventions, policies governing the features and provision of LTC services may therefore serve as a means for public health suicide prevention.

Keywords: Suicide, long-term care, policy, regulation

Brief summary –

This study evaluated the association between availability, regulation, and cost of long-term care in 16 US states and long-term care related suicide mortality among adults aged 55 and older.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is among the 10 leading causes of death in the US.1 The incidence of suicide increases over the life course, particularly after age 65,2 and rates of suicide for this age group have increased over the past decade.3 Given the high lethality of suicide attempts4 and lower likelihood of reporting suicidal ideation among older adults,5,6 there are fewer opportunities to intervene. Therefore, some argue that suicide prevention approaches targeting high-risk individuals may be less effective in later life, and instead call for a public health approach that considers points of intervention beyond acute mental health and primary care settings.7,8

This research is guided by the socioecological model of suicide, which posits that suicide risk is shaped by a diverse set of cross-cutting factors that span interpersonal relationships, community characteristics, social norms, and even political elements.8,9 The model predicts that individual suicidal actions are determined not only by individual and interpersonal factors (e.g., intergenerational family relationships and roles), but also larger familial, environmental, and social contexts that shape individual experiences. Understanding where suicidal behavior occurs may therefore provide insights regarding why it occurs and how to intervene. One setting relevant to suicide prevention among older adults is residential long-term care (LTC), including nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and independent living communities. Over 1.3 million older adults currently live in nursing homes,10 nearly one million live in assisted living facilities,10 and approximately 25% of Medicare beneficiaries currently live in age-restricted housing.11

Although LTC settings have greater supervision and less access to lethal means, evidence suggests that suicide rates in residential care settings are similar to those in community settings.12 This unexpected finding may reflect that LTC residents often experience a confluence of factors like physical illness, social isolation, loss of independence, or perceptions that one is a burden, which increase risk for suicide.12–18 Limited research suggests that facility characteristics, such as staff turnover, quality ratings, and number of beds may also be associated with suicide risk.12,19 However, because residents have frequent contact with healthcare providers, and these settings often have communal places for promoting social engagement with fellow residents, LTC facilities may be potential settings for implementing suicide prevention approaches and policies that capitalize on these features.20

State policies and regulations shape many characteristics of the LTC market including cost (e.g., Medicaid waivers), access (e.g., admissions requirements and availability of residential alternatives like adult day services), size and capacity of facilities (e.g., maximum bed size), staffing requirements (e.g. type and number), and regulation (e.g., inspection frequency, fines).21–23 Evidence suggests that these factors are associated with a host of health outcomes among residents.23–25 According to the socioecological model of suicide, these characteristics may influence suicide risk by shaping resident social engagement, interpersonal relationships, or influencing individuals’ feelings of worth and self-efficacy during LTC transitions. For instance, prior research has demonstrated that these characteristics are associated with suicide, even among those transitioning to LTC or experiencing anxiety over the transition of a loved one.12,13 While LTC regulations and facility characteristics are unlikely to directly influence individual suicide behaviors, they may serve as indicators of the joint influence of factors that are difficult to measure at the individual level, like patient health mix, staff training and turnover, or resident financial and social support. Likewise, characteristics of non-residential services, such as adult day care, may influence risk by serving as an alternative to residential LTC for individuals needing care services.

To better understand associations between LTC and suicide among older adults, we conducted an ecological study to assess the association between state policies regarding availability, regulation, and cost of residential LTC and adult day services and suicide mortality among adults aged ≥55 over a 5-year period. Using suicide mortality data from the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), which we linked to data on state characteristics, we aimed to address two questions: How do state characteristics regarding availability, cost, and regulation of residential LTC vary across states? and Is that variability in availability, cost and regulation associated with suicide mortality among older adults? We explored these questions for both suicide mortality overall and for suicide specifically related to LTC.

METHODS

Data sources

Suicide deaths.

Suicide data came from the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) from 2010–2015. The NVDRS contains categorical, coded decedent data, such as demographic information and prior health history, as well as medical examiner and law enforcement text narratives (each approximately 250 – 500 words long) abstracted by state coders. The text narratives provide detailed circumstances associated with a suicide that may not be accounted for in categorical data, such as the content of a suicide note or contributing circumstances preceding death. This analysis is limited to 16 states (AK, CO, GA, KY, MD, MA, NJ, NM, NC, OK, OR, RI, SC, UT, VA and WI) that began reporting to NVDRS by 2005, to reduce the possibility of temporal artifacts of the relative inexperience of narrative abstractors from more recently included states. This analysis is also limited to deaths reported from 2010 – 2015, the period covered by included state policy indicators.

Indicators of availability, cost, and regulation of long-term care (LTC).

These data came from three distinct sources. Data on availability of LTC providers came from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers (NSLTCP) which was available for 2012/13, 2013/14, and 2015/16. Data on cost of LTC came from reports by Genworth (2010 – 2015), an insurance company. Finally, regulation data (e.g., staffing requirements, inspection frequency, penalties) came from Trinkoff, Yoon, et al. (2020), in which the authors compiled information from administrative data sources, state websites, and regulatory compendia.22

State-level contextual characteristics.

State-specific characteristics were abstracted from the American Community Survey (ACS) for each study year. These characteristics included total population; population aged 55+; percent of population that is White race; insurance coverage (i.e., percent with any insurance, percent with Medicare, percent with Medicaid); percent of population that is foreign born; percent married; and average household income. These characteristics were used to adjust for state-level factors that may be associated with both state-specific long-term care indicators and suicide risk.

This analysis was determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan.

Measures

Exposures: State-specific indicators of long-term care.

Availability of long-term care.

Availability was indexed by two measures from NLSTCP – average served and average capacity. Average served was calculated as the total number of users divided by the total number of facilities for a state each year. Average capacity was calculated as the mean daily allowable capacity across all facilities for a state. Both average capacity and average served were calculated separately for assisted living facilities, nursing homes, and adult day services.

Cost.

We considered annual median cost (in dollars) of five different services/providers: assisted living facilities, adult day services, home health, private room in a nursing home, and semi-private room in a nursing home. We examined correlations between cost indicators, found they were highly correlated (see Supplemental Table 1), and therefore we only present findings for the cost of assisted living, which had a r2 correlation ranging from 0.77 to 0.84 with the other cost indicators.

Regulation.

Regulatory indicators were frequency of inspections (e.g., every 12, 24, or 48 months), fines levied for violations, and specific penal regulations. Penal regulations included conditional probationary licenses, temporary management, limited/suspended new admissions or service provisions, directed in-service training, mandated staffing numbers and/or qualifications, staff monitoring, resident transfer, intermediate sanction/suspension, and closure. From this set we created a total regulation sum score for each state (range 0 to 6), where presence of a given penal regulation = 1, and a lack of the regulation=0. Data on fines and penal regulations were limited to 2017, whereas data on frequency of regulations was limited to 2015.

Outcomes: Suicide mortality

Suicide deaths.

Suicide data was derived from NVDRS, which included information on a total of 25,040 suicides among those aged 55+ from 2010 – 2015. State-specific cumulative incidence of suicide was calculated by dividing the number of suicides among those aged 55+ per state per year by the state population aged 55+ per year.

Suicide deaths associated with LTC.

Suicides associated with LTC were identified using NVDRS text narratives. This method was used because prior work has shown that NVDRS data does not accurately indicate whether a decedent was residing in LTC at the time of self-injury (e.g., nursing homes may be miscoded as hospitals),12 nor does the NVDRS data indicate whether a decedent was in the process of transitioning into, or out of, LTC at the time of their death.

To address this gap, we developed a natural language processing (NLP) algorithm to analyze NVDRS text narratives to identify cases related to LTC.26 As described previously, we developed this algorithm using a four-step process:

We manually annotated a ‘training’ dataset whose true status (i.e., related to LTC or not) was determined through consensus agreement.18 Cases were considered “related to” LTC if the narrative text indicated that the decedent was (a) residing in a LTC facility, (b) moving into or anticipating moving into a LTC facility, or (c) expressed anxiety about a loved one living in or transitioning into LTC.

We converted remaining text narratives into a matrix of brief sequences of words (e.g., ‘felt ill’) that capture subject/verb or noun/adjective, etc. elements of language.

We applied a random forest classifier to predict whether the test narratives were a case based on annotated training data. The algorithm then assigned a probability of being a “case” to each testing narrative.

We manually reviewed a sample of the results, annotated their ‘true status’ via consensus as in step 1, added them to the training data, and re-ran the classifier in an iterative manner.

Once we were satisfied with algorithm performance (e.g., precision and recall), we applied it to the entire analytic sample (25,040 decedents aged 55+ from 2010 to 2015) to identify those related to LTC.18 We identified 382 suicides associated with LTC in some manner. As with overall suicide deaths, this outcome was modeled both as an annual state-specific count and cumulative incidence.

Statistical Analysis

First, we used descriptive statistics to characterize LTC availability, cost, and regulation and suicide deaths across the 16 NVDRS states from 2010 to 2015. Next, two-way fixed effect linear models were used to estimate the longitudinal association between state LTC characteristics and frequency and cumulative incidence of suicide (overall and associated with LTC) among adults aged 55+. The two-way fixed effect model accounts for state factors that may confound the association between LTC characteristics and suicide risk. For each outcome we estimated an unadjusted model and a model that adjusted for state characteristics from the ACS described above. The count and cumulative incidence of suicide were log-transformed for analysis; a value of 1 was assigned for frequencies of zero. Finally, regulation data were only available for one point in time. Therefore, for this exposure we fit an ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression where the outcome was total suicides (from 2010 – 2015) per state. As with the two-way fixed effects models, we fit both unadjusted and adjusted OLS models, but only using data from the 2010 ACS for adjustment.

The NLP algorithm was developed using Python (version 3.7.0) and Scikit-Learn (version 20.1). All statistical analyses were conducted using R Studio (version 1.1.442) and all p-values refer to two-tailed tests.

RESULTS

There was considerable heterogeneity in state contextual factors and characteristics related to availability, regulation, and costs of residential LTC across the 16 states included in analysis (Table 1). For example, annual cost of a private nursing home room ranged from $52,104 to $281,415. In models including only state-level contextual factors, both greater total state population and greater percent of residents on Medicare were associated with significantly greater cumulative incidence of LTC-related suicide mortality, but these factors were not associated with the cumulative incidence for adults age 55+ overall (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 1:

Descriptive characteristics of suicide deaths and state-level indicators of long-term care availability, regulation, and cost in 16 states, 2010 – 2015

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Suicide Deaths | |||

|

| |||

| Annual number of suicides age 55+ | 4173.3 | 379.8 | (3721, 4634) |

| Annual number of suicides age 55+ per state | 260.8 | 118.7 | (32, 545) |

| Annual number of suicides related to LTC | 82.8 | 10.15 | (66, 91) |

| Annual number of suicides related to LTC per state | 5.6 | 3.2 | (0, 13) |

|

| |||

| State-level Indicators of Long-Term Care | |||

|

| |||

| Availability | Mean | SD | Range |

|

| |||

| Average served (Number of Users/Number of Facilities) | |||

| Assisted Living | 37.3 | 17.7 | (10, 83) |

| Adult Day Services | 32.5 | 22.8 | (13, 93) |

| Nursing Home | 81.3 | 22.2 | (33, 125) |

| Average Capacity (Number of beds per Facility) | |||

| Assisted Living | 44.2 | 20.9 | (12, 97) |

| Adult Day Services | 51.1 | 22.8 | (23, 124) |

| Nursing Home | 99.3 | 21.5 | (39, 144) |

|

| |||

| Regulation* | Value | SD | Range |

|

| |||

| Modal Frequency of Inspections | Every 12 Months | NA | (12, 48) |

| Mean Fines Levied… | |||

| Per Violation | 7100 | NA | (500, 10000) |

| Per Violation per Day | 750 | NA | (500, 1000) |

| Annually | 25000 | NA | NA |

| Modal Number of State Regulations for Assisted Living | 3 | NA | (0, 6) |

|

| |||

| Cost (Annual Rate in US$) | Mean | SD | Range |

|

| |||

| Assisted Living | 44,255.9 | 11,471.7 | (28200, 72000) |

| Adult Day Services | 17,516.7 | 4,477.2 | (10140, 31826) |

| Home Health | 46,885.9 | 5,638.3 | (38896, 60632) |

| Nursing home: Private room | 96,333.6 | 42,584.4 | (52104, 281415) |

| Nursing home: Semi-private room | 89,505.8 | 46,117.6 | (47450, 281415) |

|

| |||

| State-level Contextual Indicators | |||

|

| |||

| Mean | SD | Range | |

| Population Size Aged 55+ | 136,2971.0 | 73,1330.3 | (140202, 2782562) |

| Average Income | 75,508.7 | 13,732.8 | (51849.7, 108524.0) |

| Percent White | 83.5 | 8.4 | (66.3, 94.3) |

| Percent without Health Insurance | 6.0 | 2.3 | (1.2, 13.8) |

| Percent on Medicare | 54.4 | 3.9 | (41.1, 60.0) |

| Percent on Medicaid | 12.5 | 2.7 | (8.0, 19.0) |

| Percent Foreign Born | 9.0 | 5.2 | (1.5, 24.0) |

| Percent Married | 60.0 | 3.0 | (53.7, 69.5) |

All values represent the average state-level value from 2010 – 2015 except for regulation, which was only available for 2015/2016.

Standard deviation values are not provided for regulation as states vary in whether they report fines per violation, per day there is a violation, or as an annual maximum, and within those categories there were only a few values represented across all the states.

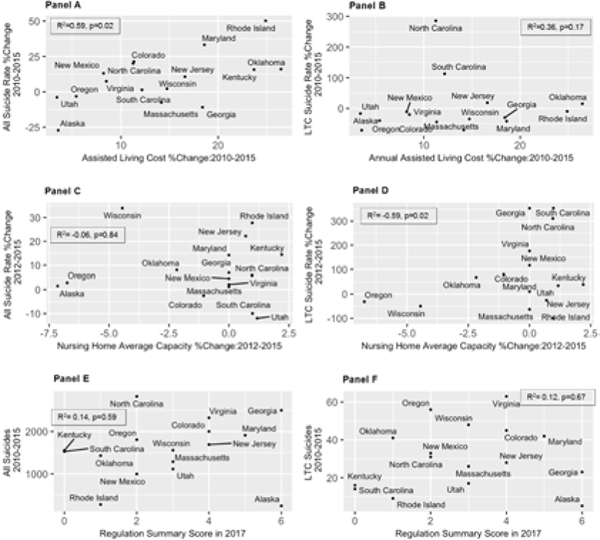

Figure 1 illustrates percent change in suicide rates both overall (Panels A, C and E) and related to LTC (Panels B, D and F) between 2010 and 2015 by select LTC characteristics. Crude Pearson correlation coefficients are provided for each panel. There was a moderate positive correlation between percent change in cost of assisted living and percent increase in overall suicide rate for older adults (r2=0.59, p=0.02), indicating greater increases in cost were positively associated with suicide mortality. However, cost of assisted living was not significantly correlated with the rate of suicide related to LTC (r2=0.36, p=0.17). There was no clear correlation between change in nursing home capacity and change in either the overall rate (r2=−0.06, p=0.84); where was an inverse relationship between change in nursing home capacity and the LTC-related rate of suicide (r2=−0.59, p=0.02). Finally, a greater number of statewide LTC regulations was not correlated with suicide mortality, either overall or related to LTC.

Figure 1:

Relationship between change in state-level indicators of cost, availability, and regulation of long-term care and change in the annual suicide rate among adults aged 55+ in 16 states, 2010 – 2015

Percent change in indicators of long-term care availability and cost with percent change in the suicide rate (overall and related to long-term care specifically). Panel A: Relationship between percent change in the cost of assisted living (2010 to 2015) and percent change in the total suicide rate among adults aged 55+ over this same period. Panel B: Relationship between percent change in the cost of assisted living (2010 to 2015) and percent change in the suicide rate related to long-term care among adults aged 55+ over this same period. Panel C: Relationship in percent change in average nursing home capacity (2012 to 2015) and percent change in the total suicide rate among adults aged 55+ over this same period. Panel D: Relationship in percent change in average nursing home capacity (2012 to 2015) and percent change in the suicide rate related to long-term care among adults aged 55+ over this same period. Panel E: Relationship between assisted living regulation score in 2015/2016 and the total number of suicides among adults aged 55+ from 2010 to 2015. Panel F: Relationship between assisted living regulation score in 2015/2016 and the total number of suicides related to long-term care among adults aged 55+ from 2010 to 2015

Availability

After adjusting for state-level characteristics, greater average nursing home capacity was significantly associated with increase in the cumulative incidence of suicide related to LTC (β=0.087, SE=0.026, p<.01), but not to the overall cumulative incidence of suicide (Table 2). In contrast, greater average capacity of adult day service facilities was significantly inversely associated with cumulative incidence of suicide overall (β=−0.004, SE=0.001, p<.01), but not with LTC-related suicide. The cumulative incidence of suicide, overall or related to LTC, was not associated with average number of users served in nursing homes, adult day services, or assisted living facilities.

Table 2:

Relationship between state-level indicators between long-term care availability and cost and state-specific suicide count among older adults in 16 states: 2010 – 2015

| Outcome (ln-transformed) All suicides among adults aged 55+ | Outcome (ln-transformed) Suicides related to long-term care among adults aged 55+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Indicator of Availability | Unadjusted Beta (SE) | Adjusted Beta (SE) | Unadjusted Beta (SE) | Adjusted Beta (SE) |

|

| ||||

| Average Capacity of Nursing Homes | −0.0003 (0.014) | −0.008 (0.016) | 0.040 (0.051) | 0.087* (0.026) |

| No. Observations | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| R2 | 0.00002 | 0.372 | 0.012 | 0.402 |

| Average No. Served by Nursing Homes | −0.010 (0.011) | −0.019 (0.014) | 0.090 (0.069) | 0.060 (0.075) |

| No. Observations | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| R2 | 0.032 | 0.412 | 0.081 | 0.372 |

|

| ||||

| Average Capacity of Adult Day Services | −0.004* (0.001) | −0.004* (0.001) | 0.002 (0.009) | 0.001 (0.011) |

| No. Observations | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 |

| R2 | 0.120 | 0.545 | 0.001 | 0.363 |

| Average No. Served by Adult Day Services | −0.001 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.013 (0.015) | 0.016 (0.020) |

| No. Observations | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 |

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.416 | 0.016 | 0.379 |

|

| ||||

| Average Capacity of Assisted Living | 0.005 (0.005) | 0.003 (0.005) | −0.001 (0.020) | 0.033 (0.027) |

| No. Observations | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| R2 | 0.063 | 0.369 | 0.001 | 0.405 |

| Average No. Served by Assisted Living | 0.003 (0.004) | 0.001 (0.004) | 0.001 (0.004) | 0.016 (0.032) |

| No. Observations | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| R2 | 0.016 | 0.362 | 0.001 | 0.369 |

|

| ||||

| Average Cost of Assisted Living | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00002 (0.00002) | −0.00003 (0.00003) |

| No. Observations | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| R2 | 0.001 | 0.077 | 0.009 | 0.123 |

Estimates are from two-way fixed effects linear models (state and year) from 2010 – 2015.

Adjusted models account for state-level characteristics including population aged 55+, percent without health insurance, percent on Medicaid, percent on Medicare, percent foreign-born, average household income, percent nonHispanic white, and percent married.

p<0.05.

Costs and Regulations

Average cost of assisted living was not associated with either overall or LTC-related suicide in adjusted or unadjusted models (Table 2). We did not find evidence of an association between the number of LTC regulations and either overall or LTC-related suicide incidence (Supplemental Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study explored the relationship between state policies and characteristics of access, regulation, and cost of residential LTC and suicide mortality among older adults. It leveraged several methodological tools, including linking multiple data sources and using a supervised machine learning algorithm to identify suicide cases related to LTC. We found that greater average nursing home capacity was associated with higher cumulative incidence of suicides related to LTC; however, capacity was not related to the overall suicide rate. Capacity of adult day service facilities was inversely associated with cumulative incidence of suicide overall, but not to LTC-related suicide. Neither cost nor regulation indicators were associated with suicide rates. This study is one of the first to examine whether policies that shape LTC characteristics are related to suicide risk among older adults, and our findings provide evidence that suicide risk for older adults living in the community, not just those living in LTC, may be influenced by state policies governing residential care.

Numerous studies have linked sociopolitical factors with suicide mortality.27,28 For example, state policies limiting gun ownership are associated with reductions in suicide deaths.29 Similarly, Anderson et al. (2014) found decreased rates of suicide among men in states that legalized medical marijuana.30 Prior studies have shown that residential care facility characteristics such as greater facility size, staff turnover, and better quality metrics are associated with more suicide deaths in LTC facilities.12,19,31,32 The present findings are consistent with and extend this work by showing an association between state average nursing home capacity and higher cumulative incidence of suicide related to LTC. Facility size may influence suicide in several ways: for instance, larger nursing homes may reflect greater community demand for specialized LTC services and thus less selectivity in terms of residents’ medical and psychiatric needs at entry. Alternatively, larger nursing home capacity may indicate fewer nursing staff hours per resident,33 less frequent monitoring of resident mental health, and lower engagement with care providers.34–36 Regardless of the specific processes determining this association, an association at the state level is meaningful, as it indicates that suicide risk in LTC may be responsive to statewide policies shaping this sector.22–25 The potential influence of policies governing LTC size and capacity therefore parallels that of other state policies.29,30,37

Although there was substantial variability in both cost and regulation of LTC, we found no evidence that these characteristics were associated with suicide mortality among older adults. It may be that these characteristics do not adequately proxy individual experiences or resources that might influence suicidality. Moreover, enforcement of said regulations may vary significantly across (or even within) states, limiting our ability to detect an association between these factors and suicide mortality. Alternatively, the lack of associations may indicate interacting processes: for instance, more expensive private-pay residential care might be cost-prohibitive for older adults with greater medical and psychiatric needs, which are risk factors for suicide.12–18 Such facilities may provide more resources to address complex health comorbidity for their residents, which would likely reduce suicide risk.

Strengths and limitations

This paper illustrates several methodological innovations. First, we applied an NLP algorithm we previously developed to identify suicide deaths related to LTC. Second, we linked NVDRS data, the most comprehensive source for understanding circumstances of suicide deaths in the US, to a diverse set of external data sources on services and regulations, allowing us to explore hypotheses about ecological correlates of suicide mortality.38 Finally, our modeling approach allowed control of variables that may confound the association between state policies and suicide risk.

The primary limitation of this study is the ecological design. As such, the study results cannot be used to make inferences about causes of suicide risk at the facility- or individual-level. Second, although our analytic approach attempted to account for state-level confounding factors, we did not have information on potentially important contextual variables such as availability of mental health services or community burden of psychiatric disorders. Lastly, the NVDRS includes data from 16 states and is therefore not nationally representative.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Our findings have implications for the approximately 3 million older adults currently living in residential LTC and their families. The disproportionate and growing burden of morbidity, mortality, and social isolation experienced by LTC residents due to the current COVID-19 pandemic highlights the need to understand how relevant state policies and LTC characteristics influence health and well-being, mental and physical, of residents.39,40 These new challenges also warrant further consideration of how service provision for vulnerable older adults might impact well-being in the broader community. Such knowledge can strengthen public health approaches to promoting mental health, including efforts to prevent suicide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The sponsor played no role in the conduct of the research or decision to publish this work.

Funding sources: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R21-MH108989).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2017. Natl vital Stat reports. 2019;68(6):1–77. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_06-508.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Orden K, Conwell Y. Suicides in Late Life. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):234–241. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0193-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. Published 2005. Accessed March 15, 2020. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conwell Y, Thompson C. Suicidal Behavior in Elders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(2):333–356. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crosby AE, Cheltenham MP, Sacks JJ. Incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior in the United States, 1994. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29(2):131–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1999.tb01051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIntosh JL, Santos JF, Hubbard RW, Overholser JC. Elder Suicide: Research, Theory and Treatment. American Psychological Association; 1994. doi: 10.1037/10159-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Orden KA, Conwell Y. Issues in research on aging and suicide. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(2):240–251. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1065791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caine ED. Forging an Agenda for Suicide Prevention in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):822–829. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butchart A, Phinney A, Check P VA. Preventing Violence: A Guide to Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Violence and Health.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Lendon JP, Rome V, Valverde R, Caffrey C. Long-term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2015–2016. Vital Heal Stat. 2019;3(43). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_43-508.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman VA, Spillman BC. The Residential Continuum From Home to Nursing Home: Size, Characteristics and Unmet Needs of Older Adults. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S42–S50. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mezuk B, Lohman MC, Leslie M, Powell V. Suicide Risk in Nursing Homes and Assisted Living Facilities: 2003–2011. Am J Public Heal. 2015;105(7):1495–1502. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mezuk B, Rock A, Lohman MC, et al. Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(12):1198–1211. doi: 10.1002/gps.4142 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cukrowicz KC, Cheavens JS, Van Orden KA, Ragain RM, Cook RL. Perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2011;26(2):331–338. doi:DOI: 10.1037/a0021836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Orden KA, Simning A, Conwell Y, Skoog I, Waern M. Characteristics and Comorbid Symptoms of Older Adults Reporting Death Ideation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(8):803–810. doi:DOI: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193–204. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T4S-46HFPC7-8/2/f32429a7c8317765b694c24a72acc3c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip PSF, Caine ED. Employment status and suicide: the complex relationships between changing unemployment rates and death rates. J Epidemiol Community Heal. 2011;65(8):733–736. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.110726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mezuk B, Ko TM, Kalesnikava VA, Jurgens D. Suicide Among Older Adults Living in or Transitioning to Residential Long-term Care, 2003 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195627. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osgood NJ, Brant BA, Lipman A. Suicide Among the Elderly in Long-Term Care Facilities. Greenwood Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Promoting Emotional Health and Preventing Suicide. SMA10–4515. Published 2010. Accessed March 10, 2020. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Promoting-Emotional-Health-and-Preventing-Suicide/SMA10-4515 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kisling-Rundgren A, Paul DP, Coustasse A. Costs, Staffing, and Services of Assisted Living in the United States. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2016;35(2):156–163. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trinkoff AM, Yoon JM, Storr CL, Lerner NB, Yang BK, Han K. Comparing residential long-term care regulations between nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(1):114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han K, Trinkoff AM, Storr CL, Lerner N, Yang BK. Variation Across U.S. Assisted Living Facilities: Admissions, Resident Care Needs, and Staffing. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2017;49(1):24–32. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trinkoff AM, Han K, Storr CL, Lerner N, Johantgen M, Gartrell K. Turnover, Staffing, Skill Mix, and Resident Outcomes in a National Sample of US Nursing Homes. JONA J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(12):630–636. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trinkoff AM, Lerner NB, Storr CL, Han K, Johantgen ME, Gartrell K. Leadership education, certification and resident outcomes in US nursing homes: Cross-sectional secondary data analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calvo RA, Milne DN, Hussain MS, Christensen H. Natural language processing in mental health applications using non-clinical texts. Nat Lang Eng. 2017;23(5):649–685. doi: 10.1017/S1351324916000383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wray M, Colen C, Pescosolido B. The Sociology of Suicide. Annu Rev Sociol. 2011;37(1):505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yip PSF, Caine E, Yousuf S, Chang S-S, Wu KC-C, Chen Y-Y. Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2393–2399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anestis MD, Anestis JC. Suicide Rates and State Laws Regulating Access and Exposure to Handguns. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2049–2058. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson DM, Rees DI, Sabia JJ. Medical Marijuana Laws and Suicides by Gender and Age. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2369–2376. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osgood NJ, Brant BA. Suicidal behavior in long-term care facilities. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1990;20(2):113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1990.tb00094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osgood NJ. Environmental factors in suicide in long-term care facilities. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22(1):98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1992.tb00478.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrington C, Swan JH, Carrillo H. Nurse Staffing Levels and Medicaid Reimbursement Rates in Nursing Facilities. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3p1):1105–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00641.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon JY, Kim H, Jung Y-I, Ha J-H. Impact of the nursing home scale on residents’ social engagement in South Korea. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2016;28(12):1965–1973. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnelle JF, Simmons SF, Harrington C, Cadogan M, Garcia E, Bates-Jensen MB. Relationship of Nursing Home Staffing to Quality of Care. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(2):225–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00225.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spilsbury K, Hewitt C, Stirk L, Bowman C. The relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(6):732–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santaella-Tenorio J, Cerdá M, Villaveces A, Galea S. What Do We Know About the Association Between Firearm Legislation and Firearm-Related Injuries? Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):140–157. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boulifard D, Pescosolido BA. Examining Multi-Level Correlates of Suicide by Merging NVDRS and ACS Data. SSRN Electron J. 2017;CES-WP-17-. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2930147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flint AJ, Bingham KS, Iaboni A. Effect of COVID-19 on the mental health care of older people in Canada. Int Psychogeriatrics. Published online April 24, 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220000708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simard J, Volicer L. Loneliness and Isolation in Long-term Care and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):966–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.