Abstract

Global education is a well-known positive externality associated with children-parents knowledge spillover. More education may also lead to increased communication among family members regarding health knowledge and skills acquired at or after school, positively affecting health behavior. One important aspect that should be considered by policy makers is the potential promotion of social behavior adapted to the COVID2019 pandemic via the education system. The current study attempts to investigate the relationships between infection and recovery rates from coronavirus and the educational achievement of the population at the US statewide level. Based on the ranking of US States (including US sponsored areas) according to the percent of the population that completed high school and above from the top (93%) to the bottom (68.9%), findings suggest that as the level of educational achievement drops, projected infection rates rise and projected recovery rates drop. Research findings demonstrate the importance of educational achievement in addressing the coronavirus pandemic. Specifically, avoiding closings and opening the school systems under the appropriate limitations may have the long-run effect of children-parents knowledge spillover regarding the COVID19 pandemic. This, in turn, might promote public re-education and spread the adoption of desirable social behavior under conditions of COVID19 pandemic, such as, social distancing and wearing masks.

Keywords: COVID-19, Global education, Risk factors, Knowledge spillover, Externalities

1. Introduction

COVID19 is a global pandemic with lethal repercussions (9.336 million dead persons worldwide as of August 8, 2021). Addressing the COVID19 pandemic has to be carried out globally; otherwise, the spread of the pandemic cannot be effectively halted. The COVID19 pandemic is associated with a large negative externality. This emanates from the difficulty to internalize the effects of economic and social activities on the infection risk of others and consequently the engage in inadequate social distancing (Bethune & Korinek, 2020; Durante, Guiso, & Gulino, 2020). Based on US calibrated epidemiological models, Bethune and Korinek (2020) evaluate the true US social cost of an additional infection (around $286,000) to be more than three times higher compared to the perceived cost by a private agent (around $80,000). Durante et al. (2020) define civic capital (or civic culture) as: “those persistent and shared beliefs and values that help a group overcome the free-rider problem in the pursuit of socially valuable activities” (page 5). Based on calibrated epidemiological models from Italy, the authors estimate that “...if all provinces had the same civic capital as those in top-quartile, COVID-related deaths would have been ten times lower.” (Abstract).

The objective of the current study is to investigate whether higher levels of education may assist in internalizing the appropriate behavioral patterns following the COVID19 pandemic. This research hypothesis is supported empirically in the case that our findings suggest negative (positive) associations between infection (recovery) rates and levels of educational achievement. In this context, numerous studies have demonstrated the positive externality of education and the related knowledge-spillover effects (e.g., Arbel et al., n.d.; Acemoglu & Angrist, 2000; Broersma, Edzes, & Van Dijk, 2016; Carlino, Hunt, Duranton, & Weinberg, 2009; Hong, Kim, Park, & Sim, 2019; Kim & Lim, 2012; McMahon, 2018; Ruhose, Thomsen, & Weilage, 2019; Sand, 2013; Schumacher, Dias, & Tebaldi, 2014).

Considering the global nature of the COVID19 pandemic, results reported in our manuscript can be generalized to other countries. Following Arbel al.,2020a, Arbel al., 2020b, this paper provides empirical evidence that as the US population becomes more educated, COVID19 infection rates (cases÷population) are expected to drop and recovery rates (recovered÷cases) are expected to rise. Moreover, while in less educated US States, COVID19 infection rates are highly dispersed and ranges between 2.22 and 12.85%, in more educated US States infection rates are expected to approach only 0.21%.

The contribution of our study is twofold. First, to the best of our knowledge, the issues of the need for public re-education of pro-social behavior and children-parents knowledge spillover have not been discussed previously in the context of COVID19. Given that, on the one hand, lockdowns are temporary, and provide local and inefficient short-run solutions, and, on the other hand, education and children-parent knowledge spillover are global, this point might prove to be important, particularly given the potential penetration of new SARS-COV-2 variants from other countries. (e.g., New Zealand COVID Update as of August 27, 2021: 82 new cases as outbreak worsens despite nationwide lockdown (The Guardian; New Zealand Covid19)).

Education has been employed globally in the context of children-parents knowledge spillover. The academic literature demonstrates that health education received at American schools by children has increased parental physical activity (Berniell, De La Mata, & Valdes, 2013); and positive health behavior and smoking cessation in China rises with higher education of children (Liu, 2021; Xie, Xu, & Zhou, 2021). Moreover, according to De Neve and Kawachi (2017), increased educational levels may also lead to increased communication among family members regarding health knowledge and skills acquired at or after school, positively affecting health behavior (Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2010; Rowa, Neneh, & Burley, 2014). The authors review education-health relationships and children-parents knowledge spillover in the US, China, Sweden, 11 European countries, Mexico and Taiwan (e.g., De Neve and Kawachi (2017): Table 1 , page 59)). Yet, De Neve and Kawachi (2017) suggest that parents-children knowledge spillover is understudied. Finally, Everding (n.d.) suggests that increasing children's education reduces parents' long-term probability of developing depression.

Table 1.

Fractional probit.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | cases_per | cases_per | recovery_per | recovery_per |

| High School Rank | 0.0270⁎⁎⁎ | 0.00493⁎⁎⁎ | −0.0506⁎⁎ | −0.00918⁎ |

| (7.60 × 10−6) | (0.00723) | (0.0373) | (0.0787) | |

| High School Rank_SQ | −0.000383⁎⁎⁎ | – | 0.000753⁎ | – |

| (0.000470) | – | (0.0616) | – | |

| Constant | −2.612⁎⁎⁎ | −2.381⁎⁎⁎ | 0.975⁎⁎⁎ | 0.627⁎⁎⁎ |

| (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (0.000263) | (0.000174) | |

| Observations | 54 | 54 | 36 | 36 |

Notes: Robust p-values are given in parentheses.

p < 0.1.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Studies carried out in different countries demonstrate that knowledge in general and children-parent knowledge spillover in particular raise life expectancy and improve the quality of life. Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2010 found that compared to 25 year-old high-school dropouts, the average life expectancy of a 25-year-old college graduates is 8 years higher. Specifically, avoiding lockdowns and opening the school systems under the appropriate limitations may have the long-run effect of children-parents knowledge spillover regarding the COVID19 pandemic. This, in turn, might promote public re-education and spread the adoption of desirable social behavior under conditions of the COVID19 pandemic, such as, social distancing, wearing masks and becoming vaccinated against the COVID19 virus.

Second, to the best of our knowledge, this article is the first to identify the NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) problem in the context of COVID19 pandemic.1 The gap between the developed and under-developed countries in terms of the scope of COVID19 vaccination is of great concern and may be considered a NIMBY issue. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed to raise the scope of COVID19 vaccine donations to under-developed countries. The problem is the formation of new SARS-COV-2 variants imported from under-developed countries, so that the pandemic spread cannot be stopped. This NIMBY problem particularly stresses the importance of pro-social behavior (social distancing, wearing masks and becoming vaccinated against the COVID19 virus). The literature on NIMBY covers a wide array of issues such as: the evolution of international agreement on climate change (Tietenberg & Lewis, 2012: 432); the treatment of hazardous waste (Tietenberg & Lewis, 2012: 521); community obstacles to large scale solar panels (O’Neil, 2021); relocation of slums and reducing housing abandonment (Olsen, 1969: 618; Mills and Hamilton, 1992: 249) and conflict of interest between the local and global government (McDonald & McMillen, 2011: 510; O'Sullivan, 2012: 421).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology and Section 3 – the results. Finally, Section 4 concludes and summarizes.

2. Methodology

Consider the following two competing fractional probit models (e.g., Papke and Wooldridge (1996); Johnston and Dunardo (1997): 424-426; Wooldridge (2010)):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where j = 1,2; ;; where all the dependent variables are based on information obtained in August 11, 2020; X = rank of the state in terms of prevalence of educated population, namely, percent of high school graduates for the relevant age cohorts and above on a scale between 1 (=the highest prevalence) and 55 (=the lowest prevalence); (the cumulative normal distribution function); α 1j, α 2j and β 1j, β 2j, β 3j are parameters; and the cirumflex denotes estimated parameters. Unlike Eq. (2), Eq. (1) permits non-monotonic change of the corona indicator with the X value.

Appendix A reports the prevalence and ranking of high school graduates and higher in US States and sponsored areas. While the highest prevalence is in Montana with 93% (first place), the lowest prevalence is in US Virgin Islands with only 68.9% (the 55th place). New York is located in the 41st place (86.1%) and California is ranked 51st. (82.5%).

3. Results

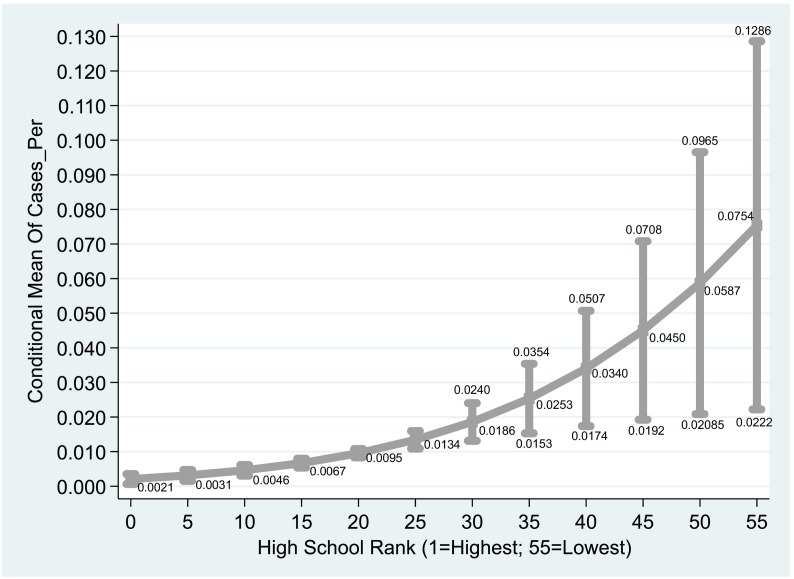

Table 1 reports the regression outcomes based on the two empirical models given by Eqs. (1), (2). Based on the projections obtained from columns (1) [(3)] in Table 1, Fig. 1 [2] reports the projected infected-population [recovery-infected] ratio in each state vs. the high school education rank (1 = the highest prevalence of educated population – high school and higher; 55 = the lowest prevalence of educated population – high school and higher).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of infected in coronavirus vs. high school rank.

Notes: . The figure is based on projections obtained from column 1 of Table 1.

The outcomes from Fig. 1 demonstrate that the projected likelihood to be infected rises from 0.0021 in the state with the highest high school rank to 0.0754 in the state with the lowest high school education rank. The implication is that the likelihood of more educated population to be infected drops. Moreover, while at the lower end (the highest prevalence of educational achievement), the 95% confidence interval around the projection is very small, at the higher end (the lowest prevalence of educational achievement) the 95% confidence interval around the projection is especially wide and stretches between 0.022 and 0.1286. A possible interpretation is that while educated people are compliant to the regulation of social distancing and mask wearing, the level of compliance among less educated populations is not uniform.

The outcomes from Fig. 2 show that projected likelihood for recovery drops from 0.9191 at the lower end (the highest prevalence of educational achievement) to 0.1932 at the higher end (the lower prevalence of educational achievement). A possible interpretation is that the level of compliance of a more educated population who were infected to the two-week period of imposed social isolation is higher than that of a less educated population.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of recovered coronavirus vs. high school rank.

Notes: . The figure is based on projections obtained from column 3 of Table 1.

4. Summary and conclusions of global aspects

Following the outburst of the COVID19 pandemic, the objective of the current study is to investigate whether higher levels of educational achievement may assist in internalizing the appropriate behavioral patterns. Numerous studies demonstrated the positive externality of education and the related knowledge-spillover effect (e.g., Arbel et al., n.d.; Acemoglu & Angrist, 2000; Broersma et al., 2016; Carlino et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2019; Kim & Lim, 2012; McMahon, 2018; Ruhose et al., 2019; Sand, 2013; Schumacher et al., 2014). Yet the contribution of our study lies in the new proposed aspects of the positive externality of educational achievement and their public policy implications.

Specifically, our study demonstrates that as the population of a US state is less educated, the projected likelihood to be infected rises from 0.0021 in the highest high school educational achievement rank to 0.0754 in the lowest rank. Moreover, while states with more educated populations seem to be more compliant with the regulation of social distancing and mask wearing, the level of compliance in states with a lower level of educational achievement is not uniform. Finally, as the population in a US State is less educated, the projected likelihood of recovery drops from 0.9191 at the lower end (the highest prevalence of educational achievement) to 0.1932 at the higher end (the lower prevalence of educational achievement).

The public policy implications of our study lie in the use of education as an important mechanism to promote compliance with the regulations and prevent the dissemination of the virus. This may be done in the form of children-parents knowledge spillover.2 To permit this possibility, it would be necessary to keep the school system open within the required limitations and encourage parents to send their children to school.

COVID19 is a global pandemic with lethal repercussions (9.336 million dead persons worldwide as of August 8, 2021). Addressing the COVID19 pandemic has to be carried out globally; otherwise, the spread of the pandemic cannot be effectively halted. Given the lack of sufficient willingness to contribute vaccinations to under-developed countries,3 the pandemic is associated with a NIMBY problem. Consequently, penetration of new SARS-COV-2 variants from other countries is a prominent concern (e.g. of the NIMBY problems: Olsen, 1969: 618; Mills and Hamilton, 1992: 249; McDonald & McMillen, 2011: 510; O'Sullivan, 2012: 421; Tietenberg & Lewis, 2012: 521; O’Neil, 2021).This makes the public education for pro-social behavior a necessity. One channel of securing pro-social behavior is education and children-parents knowledge spillover. As the relevant literature demonstrates, this is an effective tool for public education (e.g., Berniell et al., 2013 – in the United States; Liu, 2021; Xie et al., 2021 – in China; and De Neve & Kawachi, 2017: Table 1, page 59).

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest, financially or non-financially, directly or indirectly related to this work.

Footnotes

The authors are grateful to Chaim Fialkoff for helpful comments.

Britschgi (2020) discusses NIMBY and COVID19 in the context of blanket extension of deadlines for filing civil actions until 90 days after the current state of emergency ends.

In that context, Arbel et al. (n.d.) demonstrate the parents-children knowledge spillover: the matriculation diploma average of students with at least one educated parent is consistently higher by two points.

The World Health Organization director general recently called for a two-month moratorium on administering COVID-19 vaccine booster shots as a means of reducing global vaccine inequality and preventing the emergence of new SARS-COV-2 variants. He was “really disappointed” with the scope of vaccine donations worldwide.

Appendix A. Prevalence and ranking of high school graduates or higher in US States and sponsored areas

| State | High school graduate or higher | High school rank |

|---|---|---|

| Montana | 0.93 | 1 |

| New Hampshire | 0.928 | 2 |

| Minnesota | 0.928 | 3 |

| Wyoming | 0.928 | 4 |

| Alaska | 0.924 | 5 |

| North Dakota | 0.923 | 6 |

| Vermont | 0.923 | 7 |

| Maine | 0.921 | 8 |

| Iowa | 0.918 | 9 |

| Utah | 0.918 | 10 |

| Wisconsin | 0.917 | 11 |

| Hawaii | 0.916 | 12 |

| South Dakota | 0.914 | 13 |

| Colorado | 0.911 | 14 |

| Nebraska | 0.909 | 15 |

| Washington | 0.908 | 16 |

| Kansas | 0.905 | 17 |

| District of Columbia | 0.903 | 18 |

| Massachusetts | 0.903 | 19 |

| Idaho | 0.902 | 20 |

| Michigan | 0.902 | 21 |

| Connecticut | 0.902 | 22 |

| Oregon | 0.902 | 23 |

| Pennsylvania | 0.899 | 24 |

| Maryland | 0.898 | 25 |

| Ohio | 0.898 | 26 |

| Delaware | 0.893 | 27 |

| Missouri | 0.892 | 28 |

| New Jersey | 0.892 | 29 |

| Virginia | 0.89 | 30 |

| Illinois | 0.886 | 31 |

| Indiana | 0.883 | 32 |

| Florida | 0.876 | 33 |

| Oklahoma | 0.875 | 34 |

| Rhode Island | 0.873 | 35 |

| North Carolina | 0.869 | 36 |

| South Carolina | 0.865 | 37 |

| Tennessee | 0.865 | 38 |

| Arizona | 0.865 | 39 |

| Georgia | 0.863 | 40 |

| New York | 0.861 | 41 |

| West Virginia | 0.859 | 42 |

| Nevada | 0.858 | 43 |

| Arkansas | 0.856 | 44 |

| Alabama | 0.853 | 45 |

| Kentucky | 0.852 | 46 |

| New Mexico | 0.85 | 47 |

| Louisiana | 0.843 | 48 |

| Mississippi | 0.834 | 49 |

| Texas | 0.828 | 50 |

| California | 0.825 | 51 |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 0.824 | 52 |

| American Samoa | 0.821 | 53 |

| Guam | 0.794 | 54 |

| Puerto Rico | 0.747 | 55 |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | 0.689 | 56 |

References

- Acemoglu D., Angrist J. NBER/Macroeconomics Annual. 15 (1) MIT Press; 2000. How large are human-capital externalities? Evidence from compulsory schooling laws; pp. 9–59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arbel, Yuval; Bar-El, Ronen and Tobol, Yossef (2017). Equal Opportunity Through Higher Education: Theory and Evidence on Privilege and Ability. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10564, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2923649..

- Arbel Y., Fialkoff C., Amichai K., Kerner M. Can reduction in infection and mortality rates from coronavirus be explained by an obesity survival paradox? An analysis at the US statewide level. International Journal of Obesity. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-00680-7. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbel, Yuval; Fialkoff, Chaim; Kerner Amichai and Miryam Kerner (2020b). Can Increased Recovery Rates from Coronavirus be Explained by Prevalence of ADHD? An Analysis at the US Statewide Level. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berniell L., De La Mata D., Valdes N. Spillovers of healtheducation at school on parents’physicalactivity. Health Economics. 2013;22(9):1004–1020. doi: 10.1002/hec.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethune Z.A., Korinek A. 2020. Covid-19 infection externalities: trading off lives vs. livelihoods.http://www.nber.org/papers/w27009.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Britschgi C. California Nimbysaren’t letting the Covid-19 crisisgo to waste. Reason. 2020;52(3):5. [Google Scholar]

- Broersma L., Edzes A.J.E., Van Dijk J. Human capitalexternalities:effects for low-educatedworkers and low-skilledjobs. Regional Studies. 2016;50(10):1675–1687. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1053446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlino G., Hunt R., Duranton G., Weinberg B.A. Brookings-Wharton papers on urban affairs. 2009. What explains the quantity and quality of local inventive activity? pp. 65–123. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler D.M., Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in healthbehaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics. 2010;29(1):1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Neve J.-W., Kawachi I. Spillovers between siblings and from offspring to parents are understudied: a review and future directions for research. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;183(June):56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante R., Guiso L., Gulino G. Economic working paper series working paper no. 1723. 2020. Asocial capital: civic culture and social distancing during COVID-19; pp. 1–30.https://econ-papers.upf.edu/papers/1723.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob Everding (2019). “Heterogeneous spillover effects of children's education on parental mental health” HCHE Research Paper, No. 2019/18, University of Hamburg, Hamburg Center for Health Economics (HCHE), Hamburg.

- Hong G., Kim S., Park G., Sim S.-G. Female educationexternality and inclusivegrowth. Sustainability. 2019;11(12):3344. doi: 10.3390/su11123344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J., Dunardo J. 4th ed. McGraw Hill International Edition; 1997. Econometric Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.-U., Lim G. Social returns to collegeeducation:evidence from SouthKoreanCollegeEducation. Applied Economics Letters. 2012;19(16):1537–1541. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2012.654907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. Children’s education and parentalhealth:evidence from China. American Journal of Health Economics. 2021;7(1):95–130. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J.F., McMillen D.P. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon W.W. The total return to highereducation:isthereunderinvestment for economicgrowth and development? Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 2018;70(November):90–111. doi: 10.1016/j.qref.2018.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills Edwin, Hamilton Bruce. Fifth Edition. Harper Collins College Publishers; 1992. Urban Economics. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Covid19New Zealand Covid19 google search At: https://www.google.com/search?q=new zealand covid&oq=new zeala&aqs=chrome.3.69i57j46i67i433j0i67j0i131i433i512l3j0i512j0i131i433i512j0i131i433.9372j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (Lastly Accessed on August 28, 2021).

- O’Neil S.G. Community obstacles to largescalesolar: NIMBY and renewables. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. 2021;11(1):85. doi: 10.1007/s13412-020-00644-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen E.O. A competitivetheory of the housingmarket. American Economic Review. 1969;59(4):612–622. (doi:http://www.aeaweb.org/aer/) [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan A. Eight ed. McGraw Hills International Edition; 2012. Urban economics. [Google Scholar]

- Papke L.E., Wooldridge J.M. Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401(k) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics. 1996;11:619–632. [Google Scholar]

- Rowa D., Neneh A.A., Burley S.C. Children’s resistance to parents’smoking in the home and car:aqualitativestudy. Addiction. 2014;109(4):645–652. doi: 10.1111/add.12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhose J., Thomsen S.L., Weilage I. The benefits of adultlearning:work-relatedtraining,socialcapital, and earnings. Economics of Education Review. 2019;72(October):166–186. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sand B.M. A re-examination of the socialreturns to education:evidence from U.S. cities. Labour Economics. 2013;24(October):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2013.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher F.I., Dias J., Tebaldi E. Two tales on humancapital and knowledgespillovers:thecase of the US and Brazil. Applied Economics. 2014;46(23):2733. https://search-ebscohost-com.elib.openu.ac.il/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edb&AN=95992515&site=eds-live [Google Scholar]

- The GuardianThe Guardian: New Zeland COVID Update as of August 27, 2021: 82 new cases as outbreak worsens despite nationwide lockdown. At: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/28/new-zealand-covid-update-82-new-cases-as-outbreak-worsens-despite-nationwide-lockdown (Lastly accessed on August 28, 2021).

- Tietenberg T., Lewis L. 9th ed. Pearson Education Ltd.; 2012. Environmental and natural resource economics. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus calls for pause on COVID vaccine booster rollout at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-24/who-tedros-adhanom-ghebreyesus-vaccine-booster-moratorium/100401328 (Lastly Accessed on August 28, 2021).

- Wooldridge J.M. 2nd ed. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Xu W., Zhou Y. Spillover effects of adult children's schooling on parents' smoking cessation: evidence from China's compulsory schooling reform. J.Epidemiol.Commun.Health. 2021 doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215326. April. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]