Abstract

Background

Secondary hyperparathyroidism (sHPT) develops frequently in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, the burden and long-term impact of sHPT on the risk of adverse health outcomes are not well studied.

Methods

We evaluated all adults receiving nephrologist care in Stockholm during 2006–11 who were not undergoing kidney replacement therapy and had not developed sHPT. Incident sHPT was identified by using clinical diagnoses, initiated medications or two consecutive parathyroid hormone (PTH) measurements ≥130 pg/mL. We characterized sHPT incidence by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) strata, evaluated clinical predictors and quantified the association between incident sHPT (time-varying exposure) and the risk of fractures, CKD progression, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and death.

Results

We identified 2556 adults with CKD Stages 1–5 (mean age 66 years, 38% women), of whom 784 developed sHPT during follow-up. The incidence of sHPT increased with advancing CKD: from 57 cases/1000 person-years in CKD Stage G3 to 230 cases/1000 person-years in Stage G5. In multivariable analyses, low eGFR was the strongest sHPT predictor, followed by young age, male sex and diabetes. Incident sHPT was associated with a 1.3-fold (95% confidence interval 1.1–1.8) increased risk of death, a 2.2-fold (1.42–3.28) higher risk of MACEs, a 5.0-fold (3.5–7.2) higher risk of CKD progression and a 1.3-fold (1.5–2.2) higher risk of fractures. Results were consistent in stratified analyses and after excluding early events.

Conclusions

Our findings illustrate the burden of sHPT in advanced CKD and highlight the susceptibility for adverse outcomes of patients developing sHPT. This may inform clinical decisions regarding pre-sHPT risk stratification, PTH monitoring and risk-prevention strategies post-sHPT development.

Keywords: end-stage kidney disease, fracture, mortality, parathyroid hormone, SCREAM

INTRODUCTION

Secondary hyperparathyroidism (sHPT) is an important complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is characterized by elevated blood parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. sHPT develops in CKD as a consequence of abnormalities in several biochemical parameters, including increases in serum phosphorus and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), and reductions in serum calcium and vitamin D [1]. The prevalence of sHPT in CKD is well described, with estimates ranging between 20% and 80% [2] depending on the CKD severity stage [3–5]. However, there is little information about the onset (i.e. incidence) of sHPT. Incidence is potentially more useful than prevalence in understanding disease aetiology, as it allows measurement of disease burden, which is helpful for health service planning and identification of potentially modifiable risk factors.

Some [6–11] but not all [12, 13] observational studies in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD suggest that the presence of sHPT associates with a increased risk of CKD progression, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and death. Moreover, because sHPT increases osteoclastic bone resorption, prolonged sHPT has been associated with the probability of fractures in populations undergoing chronic dialysis [14, 15]. However, whether sHPT predicts the risk of fractures in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD is not well known [16]. Evidence for this derives from cross-sectional cohorts comparing patients with and without sHPT, which may suffer from immortal time bias (i.e. only those who survived to the time of sampling can contribute to the analysis) [6, 7], as well as selection bias (i.e. there are clinical differences inherent in patients with and without sHPT that can explain the outcome associations) [9, 10], leaving uncertainties regarding unmeasured confounding, reverse causation and the temporal relationship of these events.

An alternative approach to more comprehensibly quantify absolute and relative risks is to consider the development of sHPT as an intermediate event (or a time-dependent exposure) and evaluate the risk that incident sHPT confers over and above the background CKD risk. In this study we focused on quantifying incidence rates of sHPT in patients with non-dialysis CKD routinely cared for by nephrologists. We aimed to identify characteristics that predict sHPT occurrence and evaluated the adverse health outcomes associated with the development of sHPT, with special emphasis on the risk of CKD progression, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), bone fractures and death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

The study population derives from the Stockholm Creatinine Measurements (SCREAM) project, a healthcare utilization cohort from tStockholm, Sweden, described in detail elsewhere [17]. In brief, SCREAM is a repository of laboratory tests from any resident of the Stockholm who had plasma or serum creatinine measured at least once during the years 2006–11. These lab tests were linked, via each citizens’ unique personal identification number, to regional and national administrative databases with complete information on demographics, healthcare use, dispensed drugs, validated renal outcomes, diagnoses and vital status, with no loss to follow-up. The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm approved the study and informed patient consent was not deemed necessary since all data were de-identified at the government’s offices.

Study population

For this study, we included adults (≥18 years) residing in Stockholm and receiving nephrologist care from 1 July 2006 to 31 December 2011, but not undergoing kidney replacement therapy (KRT; i.e. chronic dialysis or kidney transplantation, as ascertained via linkage with the nationwide Swedish Renal Registry). From those, we selected records with at least one documented PTH measurement, with the date of the first PTH measurement set as the index date, which was the initial state. We excluded patients with a history of primary or secondary HPT (ascertained by the presence of a relevant diagnosis prior to the index date; Supplementary data, Table S2), parathyroidectomy, receiving calcimimetics or active vitamin D (defined by recorded dispensations within 6 months before index date; Supplementary data, Table S3; note that the use of vitamin D analogues was not considered an exclusion criterion) and/or having an index PTH twice above the upper reference limit (≥130 pg/mL). Other exclusion criteria included missing information on age and sex, recent or ongoing cancer (diagnosis within 3 years with the exclusion of benign skin cancers), human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus infection. A flow chart of records selection is depicted in Supplementary data, Figure S1.

Exposures and outcomes

This study contains two complementary designs. First, we analysed the incidence of sHPT and evaluated baseline predictors. The outcome was thus incident sHPT, which was defined as the date at which a diagnosis of sHPT [International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code N258] was issued, calcimimetics or active vitamin D therapies were initiated, parathyroidectomy was performed and/or two consecutive PTH tests (>3 months and ˂1 year apart) twice above the upper reference limit (≥130 pg/mL) were encountered, whichever happened first. The date of the diagnosis, the date of the first recorded pharmacy dispensation and the date of the second consecutive elevated PTH test were considered the event date.

Second, we studied adverse health outcomes associated with the development of sHPT. To this end, sHPT was considered an intermediate event, which can also be seen as a time-dependent exposure. The risks of death and MACEs were our primary study outcomes. Deaths (by any cause) were ascertained by linkage with the Swedish population register, which is considered to have virtually no loss to follow-up. MACEs were defined as the composite of death due to CVD and non-fatal MI, stroke or heart failure. The risks of fractures or CKD progression were considered secondary outcomes and progression of CKD was defined as the composite of doubling of creatinine or initiation of KRT. Fractures were defined by relevant diagnoses, excluding fractures of the face and skull. Outcome definitions are detailed in Supplementary data, Table S1.

Covariates

Study covariates include age, sex, comorbidities, concomitant medications and laboratory values. Comorbidities included the presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, CVD, cancer history, dementia, liver disease, osteoporosis and fracture history, all of them assessed using ICD-10. Medications included the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis)/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, thiazide diuretics and loop diuretics etc. Information on drug dispensations was obtained from the Dispensed Drug Registry, a nationwide register with complete information on all prescribed drugs dispensed at Swedish pharmacies. Treatments were assumed to be ongoing if there was a pharmacy dispensation at the time of or within the previous 6 months from the index date, with the exception of bisphosphonates, for which we did not impose a time limit. Covariate definitions are further detailed in Supplementary data, Tables S2 and S3.

Laboratory tests were those performed in connection with an outpatient healthcare encounter. PTH was measured by four different methods at three central laboratories in the Stockholm area. All three laboratories used second-generation assays that also measured the PTH fragments and reported the results in pg/mL. Two PTH methods specifically measured intact PTH by chemoluminescence, with a reference interval of 1.5–7.6 pmol/L. The third has a reference interval of 1.6–6.9 pmol/L and we could not retrieve information on the fourth PTH method. All plasma creatinine measurements were standardized to isotope dilution mass spectrometry standards and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation [18]. Other laboratory tests included urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (UACR), serum albumin, calcium, phosphorus, haemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, following standardized methods at the central laboratories. The closest measurements at the time of or prior to the index date were selected as baseline.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as mean [standard deviation (SD)] for continuous variables with normal distribution, median [interquartile range (IQR)] for non-normal distribution variables and percentage of the total for categorical variables. The course of patients after the index date was described by four illness–death multistate models (Supplementary data, Figure S2), with sHPT as the intermediate event and the four adverse health outcomes that we evaluated in relation to incident sHPT. All covariates were complete for all patients, with the exception of laboratory tests. Serum albumin, calcium, phosphorus and haemoglobin were missing in <20% of patients. Levels of UACR and LDL cholesterol were missing in 36.0 and 37.8% of patients, respectively. Missing data were handled using chained equations by classification and regression trees and five imputed datasets were generated.

We first evaluated the transition from baseline to incident sHPT. We evaluated baseline predictors of sHPT through Cox proportional hazards regression models. Predictors considered included demographic characteristics, comorbidities, use of medications and laboratory tests, as detailed in Supplementary data, Table S4. Continuous variables were standardized as per SD increase and the relative importance for each predictor was evaluated by the estimated explained relative risk (R2) and overall explainable log-likelihood (χ2) attributable to each predictor in the analysis of variance. Finally, we reported incidence rates of sHPT by baseline CKD stage and employed natural cubic splines to graphically illustrate the association between estimated GFR (eGFR; as a continuous variable) and the risk of developing sHPT, with a truncated power series as basis functions and knots at the 10, 50 and 90% quantiles of eGFR distribution. For these analyses, patients were followed until the occurrence of sHPT, death, emigration from Stockholm or end of follow-up (31 December 2012). End of follow-up was an administrative censoring, and the remaining censoring events were treated as non-informative censoring.

Next we considered intermediate sHPT as a time-dependent exposure, thus a patient developing sHPT during observation contributed with time to the non-sHPT group before the event and thereafter to the sHPT ‘exposed’ group. All study covariates were time-updated at the time of incident sHPT. For the outcomes of death, MACEs and CKD progression, we evaluated their association with incident sHPT via time-dependent Cox proportional hazards regression. For the outcome of fractures, we considered the possibility of the event to be recurrent and thus evaluated the association between incident sHPT and (recurrent) fractures via Poisson regression. Death was considered as a non-informative censoring event when evaluating other study outcomes, and follow-up ended otherwise at event occurrence, emigration outside the region of Stockholm or end of follow-up (31 December 2011). On the basis of biological confounders, we considered different covariates for each of the study outcomes, and these are detailed in Supplementary data, Table S4.

Several analyses were performed to test the robustness of our data. First, we excluded events within the first 90 days after sHPT to assess the impact of reverse causation bias (e.g. suspicion for an adverse event is the reason for clinical exploration that may have resulted in the detection of sHPT). Second, stratified analyses were performed to test the consistency of our results by age strata (<65 and ≥65 years), sex (men and women) and presence/absence of CVD or diabetes. Third, we evaluated the risk of unmeasured confounding by the E-value methodology, which identifies the minimum strength of association that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both treatment and outcome, conditional on the measured covariates, to fully explain the observed association. This estimates what the relative risk would have to be for any unmeasured confounder to overcome the observed association of incident sHPT with the risk of adverse events.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 2556 CKD patients without sHPT at baseline were included in our analysis. The mean age was 66 ± 15 years and 38% were women. Baseline characteristics are depicted in Table 1. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (73%), followed by CVD (43%). The use of ACEis, ARBs and beta-blockers was frequent, accounting for 68 and 51% of patients, respectively. The majority had CKD Stage 3 (62%), followed by CKD Stages 1 and 2 (28%). The median PTH value was 69 (IQR 48–93) pg/mL higher than the upper reference limit of PTH (65 pg/mL).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD at study inclusion and at the time of sHPT occurrence

| Characteristics | At study inclusion (n = 2556) | At time of sHPT occurrence (n = 784) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.4 (14.5) | 65.5 (14.2) |

| Women, n (%) | 967 (38) | 277 (35) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), median (IQR) | 38.9 (28.8–51.1) | 27.3 (20.0–35.8) |

| eGFR category, n (%) | ||

| G1–2 | 264 (10) | 16 (2) |

| G3a | 669 (26) | 64 (8) |

| G3b | 920 (36) | 244 (31) |

| G4–5 | 703 (28) | 460 (59) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 799 (31) | 329 (42) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1866 (73) | 668 (85) |

| CVD, n (%) | 1101 (43) | 415 (53) |

| Myocardial infarction | 433 (17) | 179 (23) |

| Heart failure | 562 (22) | 242 (31) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 369 (14) | 142 (18) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 343 (13) | 138 (18) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 361 (14) | 147 (19) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 36 (1) | 13 (2) |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 32 (1) | 8 (1) |

| Osteoporosis, n (%) | 149 (6) | 66 (8) |

| History of fractures, n (%) | 785 (31) | 276 (35) |

| PTH (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 69 (48–93) | 130 (95–168) |

| Albumin (g/L), median (IQR) | 37 (34–40) | 36 (33–38) |

| Calcium (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) | 2.3 (2.2–2.3) |

| Phosphate (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| Haemoglobin (g/L), median (IQR) | 128 (116–141) | 123.8 (113–135) |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 2.9 (2.2–3.7) | 2.8 (2.1–3.6) |

| UACR (mg/mmol), median (IQR) | 4.9 (1.0–38.9) | 12.6 (1.3–92.1) |

| ACEi/ARB, n (%) | 1737 (68) | 636 (81) |

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 1300 (51) | 513 (65) |

| Thiazide diuretics, n (%) | 173 (7) | 42 (5) |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 999 (39) | 505 (64) |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 344 (13) | 102 (13) |

| Vitamin D, n (%) | 294 (12) | 587 (75) |

| Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, n (%) | 91 (4) | 156 (20) |

| Phosphate binder, n (%) | 353 (14) | 188 (24) |

| Statins, n (%) | 1004 (39) | 393 (50) |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 839 (33) | 322 (41) |

| Sodium bicarbonate, n (%) | 121 (5) | 235 (30) |

| Prednisolone, n (%) | 320 (13) | 99 (13) |

| Oestrogen supplements, n (%) | 139 (5) | 35 (4) |

| Bisphosphonates, n (%) | 143 (6) | 42 (5) |

| Calcium salts, n (%) | 348 (14) | 169 (22) |

Predictors of incident sHPT

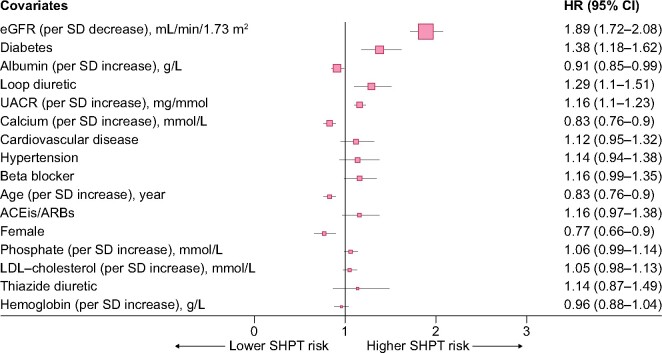

During a median follow-up of 2.4 (IQR 1.2–4.1) years, 784 subjects (31%) developed sHPT, with an overall sHPT incidence of 114.9/1000 person-years [95% confidence interval (CI) 107.0–123.2]. The majority of sHPT cases [n = 572 (73%)] were identified by the initiation of specific sHPT medications and the remaining by persistently elevated PTH values [n = 287 (26%)] or ICD diagnoses [n = 5 (1%)]. No event was identified from performed parathyroidectomies. The incidence of sHPT increased with worse CKD stages (Supplementary data, Table S5): from 57 cases/1000 person-years in CKD Stage 3 to 230 cases/1000 person-years in CKD Stage 5. Consequently, cubic splines illustrate a strong inverse association between eGFR and the risk of sHPT (Figure 1), with risks becoming apparent at eGFRs ˂45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

FIGURE 1:

Multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic splines depicting the association between eGFR (continuous variable, per mL/min/1.73 m2) and the risk of developing sHPT in patients referred to nephrologist care. Covariates used in the model are those listed in Figure 2.

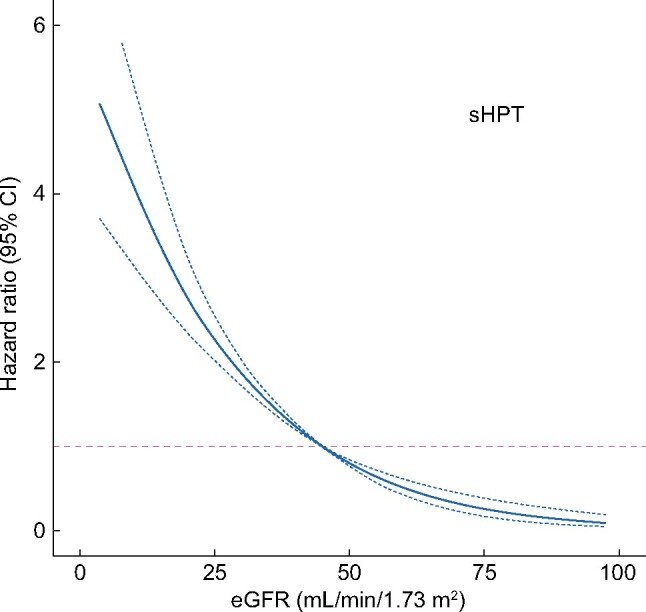

The multivariable-adjusted risk of sHPT associated with baseline predictors is shown in Figure 2: factors associated with the risk of sHPT were younger age, male sex, lower eGFR, higher UACR, higher serum calcium, lower serum albumin, presence of diabetes and use of loop diuretics. Their relative contribution is depicted graphically in Supplementary data, Figure S3: eGFR emerged as the largest contributor to the prediction of sHPT risk, followed by serum albumin levels and diabetes comorbidity.

FIGURE 2:

Forest plots depicting baseline factors associated with the risk of sHPT. Predictors are arranged from higher (on top) to lower (at the bottom) relative contribution to the full model.

Outcomes associated to incident sHPT

At the time of sHPT development, participants had lower eGFR and a higher prevalence of hypertension and CVD compared with baseline characteristics (Table 1). There was also a higher proportion of patients using ACEis, ARBs and beta-blockers. The median PTH at the time of sHPT identification was 130 (IQR 95–168) pg/mL, but PTH levels were dependent on how sHPT was identified in our study. For events identified by persistently elevated PTH values, the median PTH was 166 pg/mL and for events identified by the initiation of treatments, the median PTH was 112 pg/mL. Of these, as many as 350 (61.2% of the total number of patients identified by initiation of medications) initiated treatment at PTH levels of 100 pg/mL and 32.3% at PTH levels of 130 pg/mL.

A total of 495 deaths and 221 MACEs were recorded during a median follow-up of 2.4 (95% CI 1.2–4.0) and 2.3 (95% CI 1.1–3.9) years, respectively. Their incidence rates were higher after incident sHPT of 87.9/1000 person-years (95% CI 75.4–101.9) for death and 42.4/1000 person-years (95% CI 33.6–52.8) for MACEs compared with non-sHPT periods of 46.9/1000 person-years (95% CI 41.9–52.3) for death and 21.3/1000 person-years (95% CI 17.9–25.1) for MACEs. After multivariable adjustment, the development of sHPT was associated with a 1.4-fold [hazard ratio (HR) 1.38 (95% CI 1.05–1.83)] higher risk of death and a 2.2-fold [HR 2.16 (95% CI 1.42–3.28)] higher risk of MACEs (survival analysis with full follow-up is shown in Table 2). Sensitivity analyses excluding early events (within 90 days) from incident sHPT still showed elevated hazards (survival analysis excluding events within the first 90 days after incident sHPT shown in Table 2). Subgroup analyses gave no suggestion of heterogeneity across our pre-specified strata of age (<65 and ≥65 years), sex (men and women) and presence/absence of CVD or diabetes (Supplementary data, Table S6). E-values for the risk of all-cause mortality and MACEs were 1.81 and 2.79, respectively, which given the range of HR observed, were interpreted as moderately robust to potential unmeasured confounders (Supplementary data, Table S7).

Table 2.

Association between incident sHPT and risk of subsequent adverse health outcomes and sensitivity analysis excluding early events (within the 90 days) after sHPT development to assess the impact of reverse causation bias

| Outcome | Non-sHPT periods |

After incident sHPT |

Crude HR/RR | Adjusted HR/RR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Follow-up time (years) | Incidence rate/1000 person-years | N | Follow-up time (years) | Incidence rate/1000 person-years | |||

| Survival analysis with full follow-up | ||||||||

| All-cause deatha | 320 | 2.4 (1.2–4.1) | 46.9 (41.9–52.3) | 175 | 2.3 (1.2–3.8) | 87.9 (75.4–101.9) | 1.88 (1.55–2.28) | 1.38 (1.05–1.83) |

| MACEa | 141 | 2.3 (1.2–4.0) | 21.3 (17.9–25.1) | 80 | 2.1 (1.1–3.7) | 42.4 (33.6–52.8) | 2.04 (1.52–2.72) | 2.16 (1.42–3.28) |

| CKD progressiona | 144 | 2.3 (1.1–3.9) | 22.0 (18.5–25.9) | 149 | 1.8 (0.8–3.1) | 89.9 (76.1–105.6) | 5.26 (4.13–6.71) | 4.99 (3.47–7.17) |

| Fractureb | 930 | 2.4 (1.2–4.1) | 0.14 (0.13–0.15) | 462 | 2.3 (1.2–3.8) | 0.23 (0.21–0.25) | 1.70 (1.52–1.90) | 1.83 (1.55–2.15) |

| Survival analysis excluding events within the first 90 days after incident sHPT | ||||||||

| All-cause deathb | 320 | 2.4 (1.2–4.1) | 46.9 (41.9–52.3) | 166 | 2.3 (1.2–3.8) | 83.4 (71.2–97.1) | 1.75 (1.44–2.13) | 1.26 (0.99–1.67) |

| MACEa | 141 | 2.3 (1.2–4.0) | 21.3 (17.9–25.1) | 74 | 2.1 (1.1–3.7) | 39.2 (30.8–49.2) | 1.85 (1.37–2.48) | 1.92 (1.25–2.94) |

| CKD progressiona | 144 | 2.3 (1.1–3.9) | 22.0 (18.5–25.9) | 122 | 1.8 (0.8–3.1) | 73.6 (61.1–87.9) | 4.04 (3.13–5.21) | 4.00 (2.73–5.86) |

| Fractureb | 930 | 2.4 (1.2–4.1) | 0.14 (0.13–0.15) | 460 | 2.3 (1.2–3.8) | 0.23 (0.21–0.25) | 1.70 (1.52–1.90) | 1.81 (1.53–2.13) |

Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, CVD, dementia, liver disease, ACEis/ARBs, beta-blockers, diuretics, corticosteroid, vitamin D, ESA, phosphate binders, statin, sodium bicarbonate, prednisolone, aspirin and eGFR.

Adjusted for age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, CVD, dementia, liver disease, osteoporosis, fracture history, ACEis/ARBs, beta-blockers, diuretics, corticosteroid, vitamin D, ESA, phosphate binders, statins, sodium bicarbonate, prednisolone, aspirin, oestrogen supplements, bisphosphonates, calcium salts and eGFR.

RR: rate ratio.

A total of 293 patients had CKD progression and 1392 fracture events occurred. Again, the incidence of these events was higher after incident sHPT [89.9/1000 person-years (95% CI 76.1–105.6) for CKD progression and 0.23/1000 person-years (95% CI 0.21–0.25) for fracture] compared with non-sHPT periods [22.0/1000 person-years (95% CI 18.5–25.9) for CKD progression and 0.14/1000 person-years (95% CI 0.13–0.15) for fracture]. After multivariable adjustment, developing sHPT was associated with a 5.0-fold (95% CI 3.5–7.2) higher risk of CKD progression and a 1.8-fold (95% CI 1.5–2.2) higher relative risk of fractures. Results remained robust after excluding early events (Table 2) and we observed a suggestion of heterogeneity regarding a potentially higher risk of fracture associated with incident sHPT among patients with diabetes compared with those without (Supplementary data, Table S6). E-values for the risk of CKD progression and fracture were 5.35 and 3.06, respectively, which were interpreted as robust to potential unmeasured confounders (Supplementary data, Table S7).

DISCUSSION

Our study illustrates the high rate of occurrence of sHPT in CKD, particularly in patients with advanced CKD, where the highest sHPT incidence was observed. It also highlights the susceptibility for adverse outcomes of patients developing sHPT, who were at increased risk of fractures, MACEs, CKD progression and death compared with patients not developing this condition.

The diagnosis and management of sHPT are complex, but measuring and targeting of PTH constitutes the basis. There is currently no consensus on PTH targets for patients with non-dialysis CKD because (as opposed to patients on dialysis) there are no randomized controlled trials evaluating PTH thresholds in relation to risks. For this reason, the 2017 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines for mineral bone disorders [19] advise treatment of sHPT on the basis of the individual patient’s temporal PTH trends, with an emphasis on increasing or persistently elevated PTH values. The majority of patients with CKD Stages 3–5 [20, 21] already have PTH values above the upper reference limit of 65 pg/mL and thus we chose to define our study outcome with complementary composite events. One of them was the detection of persistently elevated PTH levels twice the upper PTH range, which is consistent with KDIGO recommendations. While our threshold (>130 pg/mL) has been used often in previous studies, we acknowledge that it is a conservative one and that treatments may be initiated at lower PTH levels. Indeed, most sHPT cases in our study were instead identified by the initiation of sHPT-related medications, which occurred in most cases at PTH values >100 pg/mL. Collectively, we believe that we have a robust and prudent assessment of sPTH that also incorporates clinical judgement and the development of patient symptoms or other laboratory abnormalities beyond PTH levels that justify treatments. By doing so, we provide novel and credible estimates of sHPT incidence in routine care settings that complement a wealth of research evaluating prevalence [3–5]. Both estimates provide complementary information, because if individuals with sHPT die more often [7, 10], the prevalence will accordingly decrease, and previous figures may signify an underestimation of true prevalence.

The development of sHPT is inherent to the impairment of kidney function [20, 21], and observational studies report an increase in PTH levels when eGFR is ˂45 mL/min/1.73 m2, which is also supported by our study (Figure 1). It is thus perhaps not surprising that our analysis of factors associated with sHPT development identified eGFR as the main contributor. Interestingly, UACR also emerged as an independent predictor, possibly reflecting additional kidney damage over that of eGFR and expanding previous reports of albuminuria differences across PTH categories of patients with CKD Stages 3–5 in cross-section [10]. The use of loop diuretics also strongly predicted sHPT in our study. It has been reported that diuretics may indirectly stimulate PTH secretion by increasing calciuria (potentially inducing a negative calcium balance), which may cause chronic parathyroid stimulation [22]. In our study, patients with diabetes were at increased risk of developing sHPT, which agrees with a study from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort showing that in patients with CKD Stages 2–4, those with diabetes had higher levels of serum phosphate, PTH and FGF23 and lower vitamin D levels compared with those without diabetes. Also in that study, sHPT occurred earlier in the course of CKD in individuals with diabetes compared with those without [23]. Underlying mechanisms are not well elucidated, but it is possible that this group possesses a greater number of characteristics predisposing them to sHPT—lower eGFR, higher BMI, greater proteinuria and lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels—in part because of greater urinary loss of vitamin D–binding protein in proteinuria [24]. This specific finding suggests that closer surveillance of PTH may be needed in diabetes. Serum phosphate did not predict sHPT risk in our study, which is at odds with the previous literature. We hypothesize that serum phosphate distribution in our cohort was narrow and that collinearity with the other covariates in our model (such as eGFR and calcium) abrogated the association. Finally, the association of low serum albumin with sHPT risk reflects the complex interplay between nutritional status [25] and bone health. Classic studies unveiled a close relationship between sHPT and energy expenditure [26] as well as subsequent weight loss [27]. It has not been until recently that underlying mechanisms have been characterized, implying the binding of PTH to receptors in both adipocytes and myocytes that lead to activation of thermogenesis genes, resulting in increased resting energy expenditure with subsequent muscle mass and fat mass loss [28]. Other identified predictors in our study, such as young age, male sex and low calcium are in line with previous reports and collectively our results credibly illustrate the multiple factors that may have an effect on the development of sHPT. As a clinical application, these findings may assist physicians in identifying populations at sHPT risk that deserve monitoring for chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) parameters and symptoms.

Our study describes an increased risk of fractures after sHPT development, a finding that expands a previous study in the general population [16] and agrees with observational evidence from populations undergoing maintenance dialysis [29–31]. Potential mechanisms involve increased osteoclastic bone resorption due to excessive calcium release to circulation [1], and cross-sectional studies indeed associate sHPT with lower bone mineral density (BMD) [32]. The causality behind these associations may be vindicated by the demonstration that correction of sHPT through parathyroidectomy [33] or calcimimetics [34] reduces the rate of clinical fractures and increases BMD [35]. Our stratified analyses suggested the possibility of a higher fracture risk associated to sHPT in patients with diabetes. This agrees with the generally higher fracture risk of adults with diabetes in the community [36] and attributed to multiple factors, including the effects of certain anti-diabetic medications (rosiglitazone and pioglitazone) on osteoclastogenesis, predisposition to fractures due to diabetes complications (like neuropathy, impaired vision or hypoglycaemia) and poor glycaemic control with subsequent accumulation of advanced glycation end-products in bone collagen [37].

We confirm previous observations of the adverse health consequences of sHPT on cardiovascular health, CKD progression and survival. By modelling sHPT as a time-dependent exposure, we potentially offer less confounded estimates and minimize immortal time biases of cross-sectional studies. Our analysis excluding early events post-sHPT development suggests robustness against reverse causation bias. However, causality cannot be inferred by our study. Despite convincing experimental mechanistic research on the deleterious consequences of acute and chronic PTH loading on the CV system, there is still no clear evidence on whether pharmacologically lowering PTH, directly [38] or indirectly [39, 40], reduces the risk of death or MACEs in patients on dialysis. However, it remains plausible that a combined medical approach targeting CKD-MBD homoeostasis may be able to achieve this.

Strengths of our analysis include the complete regional capture of patients undergoing routine nephrologist care in a country with universal healthcare access. This allows improving patient selection and minimizing confounding indication bias associated with PTH monitoring by other medical specialties. The ascertainment of kidney function by eGFR is also a strength, as kidney dysfunction is one of the strongest risk factors for elevated PTH level, but this condition is generally affected by poor awareness and underutilization of ICD diagnoses in healthcare, which cannot reliably distinguish disease severity [41, 42]. Limitations in the interpretation of our study are its retrospective nature. Data reflect routine care in the Stockholm region during 2006–11 and findings may not necessarily extrapolate to other periods or settings. The use of vitamin D analogues and cinacalcet has increased in recent years and it would be interesting to evaluate if increased sHPT treatment rates have mitigated the adverse health outcomes associated with this condition. Finally, as in any observational research, we are impacted by residual confounding due to unmeasured/undetected factors, for which we acknowledge the lack of information on body mass index and vitamin D levels. Our attempts to estimate the extent of residual confounding through the E-methodology or the exclusion of early events suggests consistency in our findings.

To conclude, our findings illustrate the burden of sHPT in CKD Stages 3–5 and describe the range of adverse health events that associate with its onset. These findings may have clinical implications: previous reports have indicated that a low proportion of patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD are regularly monitored for their PTH levels in routine care and particularly in small/rural nephrology units [43–45], potentially leading to an underuse of sHPT therapies in earlier CKD stages. Further, many persons with eGFRs <45 mL/min/1.73 m2 remain non-referred to nephrologists and PTH is less frequently monitored in primary care. Our estimates of sHPT incidence by CKD stage and predictors of sHPT risk may thus inform clinical decisions for health service planning regarding for whom and when to start monitoring PTH levels. Early identification of sHPT in primary care may also allow treatment and/or represent a reason for nephrology referral. Our outcome analyses highlight the susceptibility for adverse outcomes of patients developing sHPT, which may inform the need for risk prevention strategies post-sHPT development, particularly in surveillance and monitoring for CVD risk and fractures.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ckj online.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING

This study was supported by an unconditional grant from Vifor Pharma, the Swedish Research Council (grant number 2019-01059) and the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

M.E. reports speaker or advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma and Vifor Pharma. J.J.C. reports funding from Astellas and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work and speaker or advisory board fees from Baxter, AstraZeneca and Astellas Pharma. M.S. is a Vifor Pharma employee. P.B. and Y.X. have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cunningham J, Locatelli F, Rodriguez M.. Secondary hyperparathyroidism: pathogenesis, disease progression, and therapeutic options. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 913–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drüeke TB.Cell biology of parathyroid gland hyperplasia in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000; 11: 1141–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bureo JC, Arévalo JC, Antón J. et al. Prevalencia del hiperparatiroidismo secundario en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica estadios 3 y 4 atendidos en medicina interna. Endocrinol Nutr 2015; 62: 300–30526138703 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M. et al. Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int 2007; 71: 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andress DL, Coyne DW, Kalantar-Zadeh K. et al. Management of secondary hyperparathyroidism in stages 3 and 4 chronic kidney disease. Endocr Pract 2008; 14: 18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schumock GT, Andress D, E. Marx S. et al. Impact of secondary hyperparathyroidism on disease progression, healthcare resource utilization and costs in pre-dialysis CKD patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 3037–3048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schumock GT, Andress DL, Marx SE. et al. Association of secondary hyperparathyroidism with CKD progression, health care costs and survival in diabetic predialysis CKD patients. Nephron Clin Pract 2009; 113: c54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei Y, Lin J, Yang F. et al. Risk factors associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with chronic kidney disease. Exp Ther Med 2016; 12: 1206–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lishmanov A, Dorairajan S, Pak Y. et al. Elevated serum parathyroid hormone is a cardiovascular risk factor in moderate chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol 2012; 44: 541–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovesdy CP, Ahmadzadeh S, Anderson JE. et al. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is associated with higher mortality in men with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2008; 73: 1296–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Streja E, Wang HY, Lau WL. et al. Mortality of combined serum phosphorus and parathyroid hormone concentrations and their changes over time in hemodialysis patients. Bone 2014; 61: 201–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melamed ML, Eustace JA, Plantinga L. et al. Changes in serum calcium, phosphate, and PTH and the risk of death in incident dialysis patients: a longitudinal study. Kidney Int 2006; 70: 351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scialla JJ, Xie H, Rahman M. et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiovascular events in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25: 349–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faur D, Pérez-Bovet J, Ferrer SM. et al. Pathologic cervical fracture in a patient with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int 2013; 83: 974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danese MD, Kim J, Doan QV. et al. PTH and the risks for hip, vertebral, and pelvic fractures among patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47: 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geng S, Kuang Z, Peissig PL. et al. Parathyroid hormone independently predicts fracture, vascular events, and death in patients with stage 3 and 4 chronic kidney disease. Osteoporos Int 2019; 30: 2019–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Runesson B, Gasparini A, Qureshi AR. et al. The Stockholm CREAtinine Measurements (SCREAM) project: protocol overview and regional representativeness. Clin Kidney J 2016; 9: 119–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ketteler M, Block GA, Evenepoel P. et al. Executive summary of the 2017 KDIGO chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) guideline update: what’s changed and why it matters. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 26–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M. et al. Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int 2007; 71: 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inker LA, Grams ME, Levey AS. et al. Relationship of estimated GFR and albuminuria to concurrent laboratory abnormalities: an individual participant data meta-analysis in a global consortium. Am J Kidney Dis 2019; 73: 206–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaheer S, de Boer I, Allison M. et al. Parathyroid hormone and the use of diuretics and calcium-channel blockers: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Bone Miner Res 2016; 31: 1137–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahl P, Xie H, Scialla J. et al. Earlier onset and greater severity of disordered mineral metabolism in diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 994–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thrailkill KM, Jo CH, Cockrell GE. et al. Enhanced excretion of vitamin D binding protein in type 1 diabetes: a role in vitamin D deficiency? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 142–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikizler TA, Burrowes JD, Byham-Gray LD. et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 update. Am J Kidney Dis 2020; 76(3 Suppl 1): S1–S107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuppari L, de Carvalho AB, Avesani CM. et al. Increased resting energy expenditure in hemodialysis patients with severe hyperparathyroidism. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 2933–2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drechsler C, Grootendorst DC, Boeschoten EW. et al. Changes in parathyroid hormone, body mass index and the association with mortality in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26: 1340–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kir S, Komaba H, Garcia AP. et al. PTH/PTHrP receptor mediates cachexia in models of kidney failure and cancer. Cell Metab 2016; 23: 315–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tentori F, McCullough K, Kilpatrick RD. et al. High rates of death and hospitalization follow bone fracture among hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2014; 85: 166–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danese MD, Kim J, Doan QV. et al. PTH and the risks for hip, vertebral, and pelvic fractures among patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47: 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lertdumrongluk P, Lau WL, Park J. et al. Impact of age on survival predictability of bone turnover markers in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28: 2535–2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rix M, Andreassen H, Eskildsen P. et al. Bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in patients with predialysis chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 1999; 56: 1084–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudser KD, de Boer IH, Dooley A. et al. Fracture risk after parathyroidectomy among chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18: 2401–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moe SM, Abdalla S, Chertow GM. et al. Effects of cinacalcet on fracture events in patients receiving hemodialysis: the EVOLVE trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 1466–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behets GJ, Spasovski G, Sterling LR. et al. Bone histomorphometry before and after long-term treatment with cinacalcet in dialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int 2015; 87: 846–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Looker AC, Eberhardt MS, Saydah SH.. Diabetes and fracture risk in older U.S. adults. Bone 2016; 82: 9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gosmanova EO, Gosmanov AR.. Osteoporosis in patients with diabetes after kidney transplantation. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2017; 18: 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chertow GM, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R. et al. Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 2482–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruospo M, Palmer SC, Natale P. et al. Phosphate binders for preventing and treating chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 8: CD006023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kandula P, Dobre M, Schold JD. et al. Vitamin D supplementation in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 50–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gasparini A, Evans M, Coresh J. et al. Prevalence and recognition of chronic kidney disease in Stockholm healthcare. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 2086–2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plantinga LC, Boulware LE, Coresh J. et al. Patient awareness of chronic kidney disease: trends and predictors. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 2268–2275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DH, Johnson ES, Thorp ML. et al. Hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease: a retrospective cohort study of costs and outcomes. J Bone Miner Metab 2009; 27: 287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.London R, Sols A, Goldberg GA. et al. Examination of resource use and clinical interventions associated with chronic kidney disease in a managed care population. J Manag Care Pharm 2003; 9: 248–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winkelmayer WC, Levin R, Avorn J.. The nephrologist's role in the management of calcium-phosphorus metabolism in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2003; 63: 1836–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.