SUMMARY

Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), the enzyme responsible for synthesis of malonyl-CoA, the building block of fatty acid synthesis, is the paradigm bacterial ACC. Many reports on the structures and stoichiometry of the four subunits comprising the active enzyme as well as on regulation of ACC activity and expression have appeared in the almost 20 years since this subject was last reviewed. This review seeks to update and expand on these reports.

KEYWORDS: acetyl-CoA, carboxylase, biotin, fatty acid synthesis, malonyl-CoA

INTRODUCTION

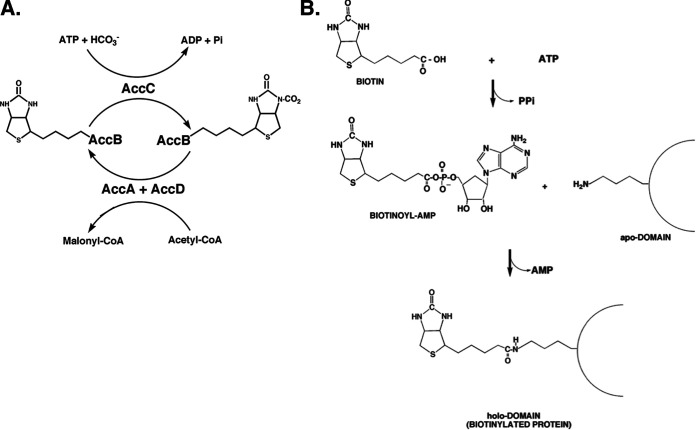

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) converts acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which is converted to malonyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP), the building block of the fatty acid moieties of bacterial membrane lipids (Fig. 1). ACC is an essential enzyme: loss of function of any of the four subunits of the active enzyme is lethal (1). Pioneering work by the laboratories of Lane (2–5) and Vagelos (6–9) showed that the enzyme is composed of two half-reactions catalyzed by three catalytic subunits now called AccA, AccD, and AccC plus a carrier protein (AccB). AccC (biotin carboxylase) catalyzes the carboxylation of the vitamin biotin which is covalently attached to AccB. In the second half-reaction, the AccA-AccD complex (carboxyltransferase) catalyzes transfer of the carboxyl group from biotin to acetyl-CoA to produce malonyl-CoA. The two half-reactions, biotin carboxylation and carboxyl transfer, reside on different subcomplexes that can be assayed separately for activity. In the first half-reaction, the biotin carboxylase subunit catalyzes carboxylation of biotin with bicarbonate in an ATP-requiring reaction. However, the natural carboxylation substrate is biotin covalently attached to the carrier protein (AccB) rather than free biotin. The second half-reaction, carboxyl transfer, requires two related proteins that copurify and transfer the carboxyl group from the carboxybiotin of AccB to acetyl-CoA to produce malonyl-CoA. In recent years, the nomenclature of the proteins has shifted from the original informal terms to that based on the Escherichia coli gene names (the E. coli gene nomenclature is now often used in the plant ACC literature). The genes were named such that the protein names would give some information about the functions of the encoded proteins. AccB was named for biotin whereas AccC was named for carboxylase, leaving AccA and AccD for the α and β subunits of the carboxyltransferase.

FIG 1.

The ACC reaction and biotin attachment to apo AccB. The acetyl-CoA carboxylase and BirA biotin protein ligase reactions. Panel A shows the acetyl-CoA carboxylase reaction, whereas panel B shows the BirA reaction, which is the general reaction of biotin protein ligases. Apo AccB is the primary translation product folded into the structure given in Fig. 2 but lacking the amide linked biotin moiety (lysine 122 has a free ε-amino group in the apo form). (Reproduced from reference 32.)

STRUCTURE AND STOICHIOMETRY OF THE ACC COMPLEX

Although the work of Lane, Vagelos, and their coworkers was exemplary, especially given the tools then available, several loose ends were tidied up by subsequent genetic analyses. One question was the composition of the carboxyltransferase component which contained two proteins of similar size (35.2 and 34.1 kDa) (2). Was the smaller protein a distinct subunit or the result of proteolysis of the larger protein? The smaller protein was shown to be a discrete subunit encoded by the accD gene, whereas the larger subunit is encoded by the accA gene (10). Another loose end was that the AccB subunit was often proteolyzed by unknown endogenous proteases during purification (6) to give smaller species of much lower activity (2). The accB gene sequence coupled with protein chemistry showed that AccB is an unusual protein composed of a tightly folded protease-resistant C-terminal half comprising the biotinylated domain whereas the remainder of the protein is largely unstructured. The sites of proteolytic cleavage are within a long 40-residue linker rich in proline and alanine residues located immediately upstream of the biotinylated domain. This linker is responsible for the aberrant migration of AccB in sodium dodecyl sulfate electrophoresis where it runs as a 22-kDa protein, whereas sequence and mass spectral data demonstrate that it is a 16.7-kDa protein (11–13). AccB is expressed in a two-gene operon with AccC, a protein of 49.2 kDa. Note that AccB is fully biotinylated under normal growth conditions in wild-type E. coli strains (2, 6). More details of the early work are described in a prior review and references therein (14).

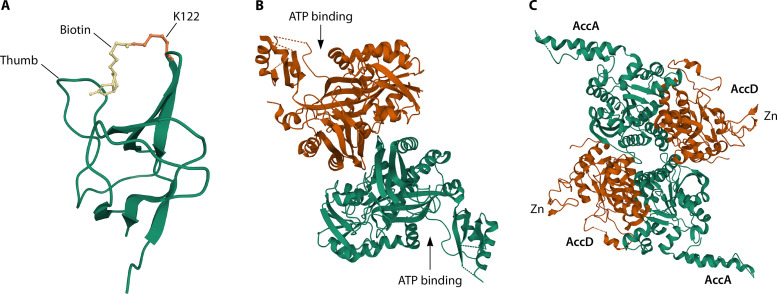

Crystal structures of the E. coli ACC component proteins are given in Fig. 2, and their properties are discussed in the legend. Note that there are numerous crystal structures of the ACC proteins of other bacteria that were often obtained in pursuit of small molecule ACC inhibitors. Several of these structures are of higher resolution than the cognate E. coli proteins, although their structures are closely similar to those of the E. coli proteins.

FIG 2.

Crystal structurers of AccB (PDB 1BDO), AccC (PDB 4HR7), and the AccA-AccD dimer of dimers (PDB 2F9Y). (A) The 1.8-Å structure of the AccB biotin domain. The AccB “thumb” domain is essential for activity and is characteristic of bacterial and plastid AccB proteins (24). The thumb interacts with the biotin moiety (PDB 1BDO) (81). Two AccB biotin domain structures obtained by nuclear magnetic resonance technique, PDB 2BDO (82) and PDB 1A6X (83), are in good agreement with the crystal structure and show that the unbiotinylated and biotinylated forms have essentially the same structure, although the structure tightens upon biotinylation (83–85). The NMR reports also demonstrate the disordered nature of the residues N-terminal to the biotin domain. (B) The 2.4-Å structure of the AccC dimer that catalyzes carboxylation of the biotin moiety of AccB (20). The “flaps” to the left (upper monomer) or right (lower monomer) close over the ATP molecules (PDB 1DV2) (86). This movement is characteristic of the Mg2+-ATP grasp protein family which includes numerous ligases. (C) The 3.2-Å structure of the AccA-AccD dimer of dimers that catalyzes transfer of the carboxyl moiety of carboxybiotinyl AccB to acetyl-CoA to form malonyl-CoA (21). The N-terminal zinc-binding domain of AccD is essential for activity (58, 62) but is not required for assembly of the AccA-AccD dimer of dimers (62). The Zn domain found only in bacterial carboxyltransferases may provide partial protection for bound acetyl-CoA (21).

The structure of the intact E. coli ACC complex remains unknown. The AccB-AccC complex purifies separately from the more stable AccA-AccD complex in E. coli cell extracts. The currently accepted subunit stoichiometry is 4AccB-2AccC-2AccA and 2AccD. However, a crystal structure of a 2AccB-2AccC complex has been reported that will be discussed below. Recent developments have provided the expression ratios of the four ACC proteins, whereas only the AccB/AccC ratio was known previously (15). The data obtained by three different mass spectral approaches plus a very different method strongly support the accepted subunit stoichiometry (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Protein copies per cell

| Protein | No. protein copies per cell determined by: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass spectral analysisa |

Ribosome profiling (18) |

|||||

| APEX (87, 88) | FASP-TPAb (89) | HRM-MS (90) | Minimal medium | Rich medium | Rich medium lacking Met | |

| AccB | 3,337 (3,258) | 1,144 | 2,900 | 5,637 | 34,495 | 13,718 |

| AccC | 1,726 (1,534) | 580 | 1,000 | 1,951 | 13,890 | 4,452 |

| AccA | 1,931 (2,088) | 629 | 1,400 | 1,800 | 10,155 | 4,753 |

| AccD | 1,187 (2,012) | 581 | 1,700 | 2,475 | 8,774 | 4,611 |

Abbreviations: APEX, absolute protein expression; FASP-TPA, filter aided sample preparation-total protein approach; HRM-MS, hyper reaction monitoring mass spectrometry; Met, methionine. The values in parentheses are from Shigella dysenteriae, a very close relative of E. coli (88).

The FASP-TPA values are low due to analysis of stationary-phase cells (89).

The results of three different mass spectral (MS) methods are given in Table 1 because protein quantitation by tandem MS of peptides remains somewhat unsettled (16). The lower values given by the filter aided sample preparation-total protein approach (FASP-TPA) method can be attributed to analysis of late-stationary-phase cells. Expression of the acc genes is under growth rate control in that rapidly growing cells have higher ACC subunit levels (17). All four proteomic studies assayed tryptic or LysC peptides derived from total proteomes.

A recently developed approach completely independent of protein/peptide properties is ribosome profiling based on the protection of mRNA sequences sequestered within ribosomes (18). The protected sequences are isolated through nuclease digestion of the unprotected mRNA regions. The protected fragments are recovered, converted to cDNA, and sequenced (18). The protected sequences show the translated mRNA sequences as well as the levels of translation of each region. The data give the number of ribosomes per mRNA, hence the number of protein molecules per mRNA (since each ribosome makes one protein), which allows quantitation of gene expression. Note that the ribosome profiling data confirm the previously reported growth rate regulation data (17): the fast-growing rich medium cultures have much higher ACC protein levels than the slow-growing minimal medium cultures (Table 1). Together with the MS analyses, these data indicate an AccA/AccD ratio of ∼1 as expected from their isolation as a 2:2 complex, whereas the ratios of AccC/AccA (or AccD) are also ∼1. Finally, the ratios of AccB to the other subunits varied between 2 and 3. Although the subunit ratios in the various analyses show some scatter, this is to be expected since these were untargeted analyses.

A third approach which predated those above gave a more accurate AccB to AccC ratio because it was relatively “hard-wired” and independent of the properties of the proteins. The approach was that of Studier and Moffatt (19) which takes advantage of the powerful phage T7 RNA polymerase and rifampin, an antibiotic that blocks E. coli RNA polymerase activity but which has no effect on phage T7 RNA polymerase activity. In the Studier-Moffatt protocol, the gene of interest is inserted into a plasmid downstream of the promoter sequence utilized by phage T7 RNA polymerase. The plasmid construct is transformed into an E. coli host strain that has the T7 RNA polymerase inserted into the host chromosome under the control of a lac promoter. Upon IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction, T7 RNA polymerase accumulates. A short time later, rifampin is added to block host transcription, and any host mRNAs are allowed to decay. The cultures are then labeled with 35S-methionine followed by separation of the labeled proteins by denaturing gel electrophoresis. Due to these manipulations, the only radioactive proteins that appear on the gels are those encoded by the genes transcribed by the accumulated T7 RNA polymerase (19).

In using this approach to obtain the AccB/AccC ratio, a DNA fragment carrying the native two-gene accBC operon lacking the native promoter was inserted into a T7 expression vector lacking the vector translation initiation sequences (15). Following completion of the Studier-Moffatt protocol, the labeled proteins were separated by denaturing gel electrophoresis and the radioactivity of each band was quantitated by phosphorimaging. Correction for the number of methionine residues in each protein allowed the AccB/AccC molar ratio to be calculated. This gave an expression ratio of 2.1:1 in cell extracts (15). Labeled AccB-AccC complexes were then isolated from the cell extracts by using the AccB biotin moiety as an affinity tag. This gave an AccB/AccC ratio of 2.8:1 in the purified fraction. The altered ratio relative to that of the cell extracts was shown due to dissociation of the complex. The slowest-migrating species on nondenaturing gels had an AccB/AccC ratio of 1.95:1, whereas faster-migrating species had lower ratios (15).

Given these data and those of Table 1 together with the well-established structures of AccC as a dimer (2, 20) and the AccA-AccD as a dimer of dimers (2, 21), the subunit composition of the active ACC complex is 4AccB, 2AccC, 2AccA, and 2AccD, which gives a molecular weight for the complex of 302 kDa. However, size exclusion chromatography indicates a complex of at least twice that size (22), which could be due to marked asymmetry of the complex and the paucity of large molecule standards. Note that size exclusion chromatography of an ACC complex of a Pseudomonas citronellolis strain gave a molecular weight consistent with that calculated above for the E. coli complex (23). However, different gel matrices were used in the two studies.

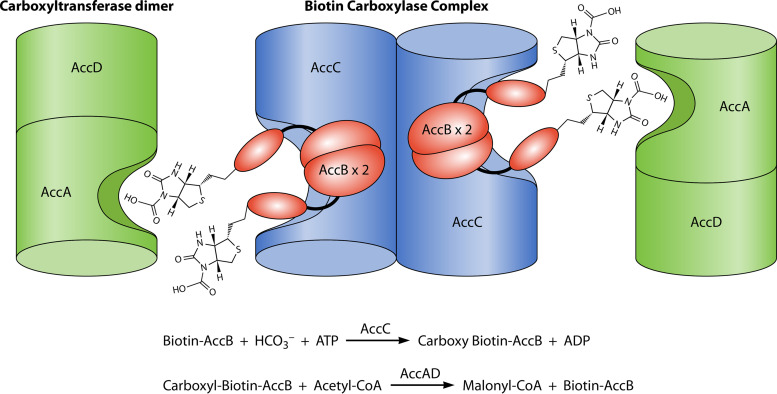

Well-documented literature reports are in agreement with the 4AccB:2AccB:2AccA:2AccD stoichiometry. AccB is reported to be dimeric in cell extracts (6), and in vivo genetic complementation studies also support AccB dimerization (24). In a detailed report based on the above subunit composition, Soriano and coworkers (25) reconstituted a highly active E. coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase from purified subunits. In titrations of malonyl-CoA synthesis versus the concentration of full-length AccB, these workers reported that 39 nM biotinylated AccB was required to give full activity in reaction mixtures containing 20 nM AccC (25). Hence, maximal ACC activity required an AccB:AccC ratio of 2:1 in agreement with the in vivo analyses (15). A cartoon representation of a possible arrangement of the ACC subunits is given in Fig. 3.

FIG 3.

Cartoon of the overall ACC reaction based on the 2AccA-4AccB-2AccC-2AccD stoichiometry. The AccB-AccC and AccA-AccD complexes are sufficiently stable for isolation in vitro and their partial reactions can be assayed directly. Note that the two AccA-AccD representations would form the 2AccC-2AccD heterotetramer behind the plane of the page.

A MISLEADING CRYSTAL STRUCTURE

An apparent contradiction with the above subunit ratios is a crystal structure of a complex containing two AccBs and an AccC dimer (26). This ratio is in direct conflict with the above data which indicate that the ratio is at least 2:1. However, there are several caveats to attributing physiological relevance to this structure. A major caveat is that the AccB subunit of the complex was in the inactive apo form rather than the biotinylated holo form (the authors state that the AccB “was at least partially biotinylated”) (26). This precluded valid determination of the enzymatic activity of the complex. Poor biotinylation of AccB can be readily attributed to the use of the very powerful T7 RNA polymerase protein expression system of Studier and coworkers (27, 28). The T7 RNA polymerase protein expression system produces so much acceptor protein and consumes so much ATP that the biotinylation capacity of the BirA biotin protein ligase is overwhelmed. This results in most (if not virtually all) of the AccB being in the unbiotinylated apo form (25, 29, 30). Although this can be remedied by simultaneous high-level expression of BirA (31), the BirA ligase is now commercially available and thus investigators generally incubate purified (or crude) apo AccB samples with BirA, ATP, and biotin followed by biotinylation quantitation by mass spectroscopy (25).

A second caveat to 2AccB-2AccC structure is that the interactions between AccB and AccC in the structure (26) involve the C-terminal AccB biotin domain whereas prior mutational studies showed that the N-terminal AccB residues are essential for complex formation (13, 15). Moreover, assays of the overall acetyl-CoA carboxylase reaction mixture containing the full-length AccB were much more active than those containing shorter proteins that contained only the biotin domain (2). Furthermore, as mentioned above, AccC overproduction blocked biotinylation of the full-length AccB but not biotinylation of the C-terminal biotin domain (32) (Fig. 4). Finally, in work contemporaneous with that of the 2AccB-AccC dimer crystal structure, affinity chromatography of cell extracts using a tagged AccC gave complexes containing all four ACC subunits (22). In the denaturing gel analysis reported in that paper, it is striking that the AccB bands are more intense than the AccA, AccD, and AccC bands despite the fact that AccB is an acidic protein that binds less of the acidic stain, Coomassie blue, than do typical proteins. Hence, AccB seemed in significant excess over AccC in these studies (22). A final caveat is that in the 2AccB-2AccC complex, the site of biotin attachment, AccB K122, is ∼40 Å removed from the AccC active site (26). This distant spacing is difficult to reconcile with the high biotin carboxylation activity seen with a fully biotinylated AccB biotin domain (33), which indicated that the AccB biotin domain moiety must have accessed the AccC active site.

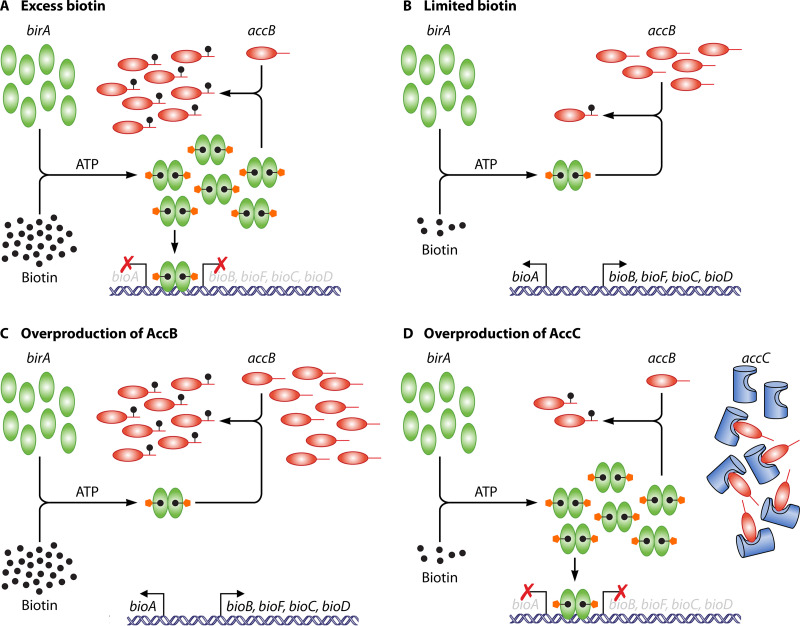

FIG 4.

The biotin regulatory system of E. coli. The bioABFCD operon has two divergent promoters controlled by a common overlapping operator. BirA is represented by green ovals, biotin by black dots, the AMP moiety by red pentagons, AccB by puce ovals, and AccC by blue cutout cans. The arrows denote transcription from the leftward and rightward bio promoters. (A to C) BirA switches from function in biotin ligation to repressor function in response to the intracellular biotin requirement indicated by the level of unbiotinylated AccB. When unbiotinylated AccB levels are high, the protein functions as a biotin ligase and transcription of the bio operon is derepressed, resulting in increased levels of the biosynthesis enzymes and of biotin. Once the unbiotinylated AccB has been converted to the biotinylated form, biotinoyl-5′-AMP is no longer consumed and remains bound to BirA. The dimeric biotinoyl-5′-AMP liganded form of BirA accumulates to levels sufficiently high that the bio operator is fully occupied, resulting in transcriptional repression of the biotin biosynthetic genes. (D) Overproduced AccC ties up unbiotinylated AccB into a complex that is a poor biotinylation substrate. Therefore, high levels of the dimeric biotinoyl-5′-AMP liganded form of BirA accumulate which result in repression of bio operon transcription. (Adapted from reference 32.)

The aberrant 2AccB-2AccC complex may be due to manipulation of the accB-accC operon. A synthetic construct was used rather than the native operon for expression of the proteins. In operons such as the accB-accC operon, genes closer to the promoter are generally translated more strongly than downstream genes (called natural polarity). The arrangement of genes in an operon provides an excellent means to control protein stoichiometry, and cotranscription of accB and accC, with accB being the upstream gene, is a dominant theme in bacteria (32). Indeed, the intergenic accB-accC regions of the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli and the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis show very similar spacings between the accB termination codon and the accC initiation codon (10 and 11 bp, respectively). Sequence length conservation between such distantly related bacteria argues that these regions play an important physiological role. In the mass spectral and ribosome profiling experiments discussed above, AccB and AccC were expressed from the intact native operon. In contrast, Broussard and coworkers constructed a synthetic operon that had a 13-bp intergenic region (26). In this construct, the native accC ribosome binding site was deleted and replaced with a canonical ribosome binding site plus a restriction site. Manipulations of such intergenic regions can have profound effects on translation of downstream genes and disrupt the stoichiometries imposed by natural selection (34, 35). Hence, the synthetic operon construct may have contributed to formation of the aberrant structure. This interpretation is supported by reports that overexpression of either AccB or AccC alone is toxic to E. coli (11, 12, 32, 36, 37). Toxicity seems almost certainly due to assembly of AccB-AccC complexes having aberrant subunit stoichiometries because no toxicity is seen when AccC is overexpressed together with AccB from the native accB-accC operon (32, 36, 37).

Interpretation of two recent kinetic studies (22, 38) seems likely to be problematic since the proteins were produced by the same protocol as that used in the 2AccB-AccC structure work (26). Hence, most of the AccB was probably in the inactive apo form rather than the active biotinylated holo form. Is apo AccB inert or does it act as an inhibitor? Inhibition seems most probable because apo AccB could bind AccC and thereby block interaction of holo AccB with AccC and an AccC monomer would be inactivated. However, because the two subunits of AccC dimers communicate (39–41), binding of apo AccB to one subunit of an AccC dimer could also inactivate the other AccC subunit even though it had bound holo AccB. Communication between the two monomers of an AccC dimer was shown by construction of hybrid dimers in which one subunit was wild-type and the other contained an active site mutation. The presence of the inactive monomer reduced activity at least 100-fold rather than the expected 50% (41). Hence, binding of a single apo AccB could essentially inactivate an AccC dimer. Therefore, the presence of apo AccB introduced an unknown variable into the kinetic analyses reported (22, 26, 41). Given the ease and simplicity of the remedy, it is a puzzle why these workers failed to ensure full biotinylation of AccB.

REGULATION OF ACC ACTIVITY BY PROTEIN-PROTEIN INTERACTIONS

Feedback Inhibition

Feedback inhibition of ACC by products of fatty acid synthesis is an attractive regulatory mechanism to prevent wasteful synthesis of malonyl-CoA when it cannot be utilized. Davis and Cronan (42) first reported that acyl-ACP species of acyl chain lengths from C6 to C20 inhibited the overall ACC reaction by about 70% whereas nonacylated ACP (ACP-SH) had no effect. Moreover, inhibition was specific in that spinach ACP I acylated with palmitate failed to inhibit. Acyl-ACPs inhibited the overall ACC reaction but had no effect on either of the half-reactions, biotin carboxylation or carboxyl transfer (42). ACC inhibition by acyl-ACP was recently confirmed using purified ACC proteins and palmitoyl-ACP and found to exhibit a significant hysteresis (38). That is, ACC inhibition by palmitoyl-ACP proceeded in a time-dependent manner. These workers (38) reported that palmitoyl-ACP did not inhibit assembly of the complex and its action was allosteric in nature. An interesting finding was that pantothenic acid, a component of the 4′-phosphophopantheine prosthetic group, was inhibitory. However, these kinetic analyses may be compromised by the presence of a significant level of apo AccB in the ACC reactions (see above).

AccB Regulates Its Biotinylation Status

AccB lacking the biotinoyl modification (apo AccB) is chemically inert and could inhibit ACC activity. In E. coli (43, 44) and several other bacteria (45, 46), accumulation of apo AccB is precluded because apo AccB accumulation stimulates the synthesis of biotin (Fig. 4) (43). This results because BirA is a bifunctional protein: it is both a biotin protein ligase and the repressor of the biotin biosynthesis (bio) operon transcription (43, 44, 46–48). In the presence of sufficient biotin and absence of apo AccB, biotinoyl-5′-AMP, the activated intermediate of the ligase reaction, accumulates stably in the active site and elicits dimerization of the otherwise monomeric BirA (47, 49). This allows the paired BirA N-terminal winged helix-turn-helix domains of the dimeric BirA–biotinoyl-5′-AMP complexes to bind the operator that tightly controls transcription of the bioABFCD operon and blocks transcription of the operon (Fig. 4). However, when apo AccB builds up, the biotinoyl-5′-AMP mixed anhydride is attacked by the ε-amino group of a specific lysine residue of the AccB biotin domain to produce biotinylated AccB (holo AccB) and AMP. The loss of biotinoyl-5′-AMP results in dissociation of the dimer which relieves repression. RNA polymerase then binds the bio operon promoters and transcribes the biosynthetic genes to give elevated levels of the biotin biosynthetic enzymes and increased biotin synthesis (43, 47, 49). Note that biotin limitation as well as expression of foreign biotin acceptor proteins also elicits derepression of the E. coli bio operon (43, 47, 49). The dedication of E. coli BirA to a single biotin acceptor protein, AccB, is unusual. Most bacteria, including its close E. coli relative, Salmonella enterica, encode more than one biotin acceptor protein (albeit <4), although they have only a single biotin protein ligase. A recent review of the simple, yet sophisticated, BirA regulation has appeared (48).

Inhibition by Nitrogen Assimilation Proteins?

Inhibition of ACC activity by binding of the PII protein of nitrogen regulation was first reported in plant chloroplasts (50). Subsequent work in E. coli which encodes two PII proteins, GlnB and GlnK, gave data similar to that seen in chloroplasts (51, 52). GlnB plays a critical role in the regulation of nitrogen metabolism by controlling the activity of glutamine synthetase via a complex regulatory system (53). Like GlnB, GlnK can control the activity of glutamine synthetase. GlnB and GlnK are both trimeric proteins, are functionally equivalent, and can form mixed GlnB-GlnK trimers. Their distinct physiological effects are due to differential expression of the two genes. GlnK regulatory activity is less potent than that of GlnB, the principal signal transducer and regulator of glutamine synthetase activity (53).

The first report of PII involvement with ACC in bacteria was in the nitrogen-fixing alphaproteobacterium, Azospirillum brasilense, where using an immobilized PII protein column, AccB was found in a complex with a PII protein called GlnZ (52). This was recapitulated with purified E. coli AccB and GlnK (51). Notably, the complex dissociated upon addition of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediate, 2-oxoglutarate, the carbon skeleton for assimilation of inorganic nitrogen. The complex was stabilized by ATP-Mg2+. Interaction of AccB with GlnK required biotinylated AccB; the apo form was inactive. Despite the GlnK-AccB interaction, addition of GlnK had no effect on ACC activity. In later work, the same group turned to GlnB and tested the AccB-AccC complex as the GlnB target (52). Indeed, GlnB bound the AccB-AccC complex but also bound AccB in the absence of AccC. As seen for GlnK, 2-oxoglutarate disrupted the complexes. Unlike that of GlnK, the addition of GlnB inhibited overall ACC activity, although the inhibition was modest (50 to 60% inhibition) (52). The effects of addition of 2-oxoglutarate on overall ACC activity were not given.

Although much effort was expended on in vitro studies of interactions of ACC with PII proteins, including the effects of a cyanobacterial protein on E. coli ACC (54), the physiological effects of these interactions remain unclear. A recent paper tested these interactions in vivo by construction of E. coli strains deleted for glnB or both glnB and glnK (55). Despite the inhibitory effects of GlnB on ACC activity in vitro, its absence in vivo failed to significantly stimulate fatty acid synthesis. The strain lacking both GlnB and GlnK showed a similar lack of stimulation. When a thioesterase was expressed to counter possible feedback inhibition by acyl-ACPs, fatty acid synthesis was stimulated by 80% in the strain lacking both GlnB and GlnK but by only 22% in the strain lacking only GlnB (55). The differences are small and confusing, especially given that GlnK had no effect on ACC activity in vitro (52). It is puzzling that a strain lacking only GlnK was not tested. Earlier work in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 showed that deletion of glnB had only modest effects on acetyl-CoA pools and fatty acid synthesis (54). From these reports, it is difficult to extract a consistent and clear picture of the effects of PII proteins on ACC activity, although the in vivo effects seem modest.

OTHER REPORTED REGULATORY MECHANISMS

Inhibition by the ppGpp Alarmone

The nucleotide alarmone, ppGpp (guanosine tetraphosphate or guanosine-3′,5′-bispyrophosphate), was reported to inhibit the overall ACC by inhibition of the carboxyltransferase half-reaction (56). Maximal inhibition was modest, about 50%. This was consistent with the effects on phospholipid synthesis. In strains lacking ppGpp, no inhibition was seen, whereas strains that accumulated ppGpp were inhibited about 60% (56). However, later work showed that inhibition of phospholipid synthesis was eliminated by overproduction of PlsB, the glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase that catalyzes the first step of E. coli phospholipid synthesis (57). PlsB overproduction eliminated ppGpp-engendered accumulation of long-chain acyl-ACPs, the feedback of which inhibited fatty acid synthesis. Hence, the reported effect on carboxyltransferase and ACC activity seems likely to not be of physiological significance. One possible explanation for the in vitro inhibition is that ppGpp could compete with the CoA moiety of acetyl-CoA because both CoA and ppGpp have rare 3′-phosphoryl groups.

Regulation of ACC Gene Transcription by mRNA Binding?

As mentioned above, in E. coli, only the accB and accC genes are cotranscribed, with accB being the upstream gene. In contrast, the genome locations of the accA and accD genes are distant from the accBC operon and from one another. This raises the question of how stoichiometric production of AccA and AccD to form the multisubunit carboxyltransferase complex is achieved. Meades and coworkers (58) reported in vitro experiments arguing that coordinated production of the AccA and AccD subunits is due to a translational repression mechanism exerted by the proteins themselves. The AccA-AccD carboxyltransferase (CT) complex was proposed to regulate its own translation by binding the accA and accD mRNAs. However, long ribosome-free mRNA molecules were required (500 to 600 bases), and such species are unlikely to exist in vivo because in E. coli, transcription and translation are very tightly coupled (59, 60). Ribosomes are loaded onto nascent mRNAs as soon as the ribosome binding site and the first few codons have been transcribed. Indeed, the NusG transcription elongation cofactor is reported to act as a bridge that links RNA polymerase to the lead ribosome (59, 60). Moreover, termination factor Rho binds ribosome-free mRNA molecules and efficiently aborts their elongation (61).

These factors plus two lines of direct evidence indicate that the proposed translational repression mechanism does not exist in vivo. The first line of evidence is that ribosome profiling shows that the accA and accD mRNAs are each bound by a full complement of ribosomes: there are no 500- to 600-base ribosome-free accA or accD mRNAs available for binding (18). Second, overproduction of the AccA-AccD carboxyltransferase tetramer had no detectable effect on translation of the CT subunit mRNAs (62). The design of these experiments again utilized the different rifampin sensitivities of the RNA polymerases of phage T7 polymerase and E. coli (19). E. coli RNA polymerase was used for overproduction of CT tetramers, whereas phage T7 RNA polymerase was used to produce the mRNAs targeted by the putative translational repression mechanism. Therefore, following accumulation of the CT tetramers and T7 RNA polymerase, further synthesis of these proteins could be blocked by addition of rifampin. In contrast, the induced T7 RNA polymerase accumulated prior to rifampin addition would continue to produce the mRNAs that are the putative targets of translational repression. Labeling with 35S-methionine specifically monitored translation of these accA and accD mRNA molecules. No detectable decrease in the synthesis of radioactive AccA or AccD was observed (62). Hence, the in vivo experiments (62) provide no support for the in vitro results reported by Meades and coworkers (58).

Regulation of acc Gene Transcription by FadR

E. coli FadR is a transcription factor regulated by acyl-CoA thioester binding that optimizes fatty acid metabolism in response to environmental fatty acids (FAs) (63, 64). FadR represses the fad genes of FA degradation (β-oxidation) and activates the fab genes of FA synthesis. Recent work has shown that overproduction of FadR activates valid, but cryptic, low-affinity binding sites in the promoters of most fatty acid synthetic genes, including the acc genes (65, 66). At the normal levels of FadR encoded by the chromosomal gene, these sites are inactive. The accB-accC operon is reported to be transcribed from two adjacent promoters rather than the single promoter reported previously (12). The newly discovered promoter is activated by FadR overproduction, whereas the prior promoter was repressed. These workers also mapped the accA promoters, both of which lie within the upstream dnaE (polC) gene which encodes the polymerase subunit of the replicative DNA polymerase III (66). One of the promoters is that described previously (17) which seems repressed by FadR, whereas the upstream second promoter is stimulated by FadR overproduction (66). However, overproduction of FadR results in greatly increased synthesis of fatty acids (8- to 25-fold). Very high FadR production compromises growth and results in abnormally large cells that contain intracellular membranes (67). Hence, use of this extra synthetic capacity is deleterious and seems likely to be reserved for instances where the cell envelope is attacked (63). As mentioned above, overproduction of AccB inhibits growth, although several generations are required before growth ceases. Induction of AccB overproduction resulted in greatly decreased accBC expression within 30 min, whereas expression of accA and accD was unchanged. The decrease was independent of biotinylation and was specific to the N-terminal 68 residues of AccB (plus the upstream region), which was extremely toxic to growth (11, 37). Substituting the B. subtilis AccB N-terminal region for that of E. coli restored normal function (37). Replacement of both accBC promoters with the lacZYA promoter also restored normal function (37). Although these data indicate some form of AccB autoregulation, the mechanism remains mysterious. These phenomena should be revisited in light of regulation exerted by RNA molecules such as small RNAs and riboswitches that could target the unusually long untranslated region (>300 bp) between the P1 and P2 promoters and the accB coding sequence.

SALIENT ASPECTS OF PLANT ACCS

There are interesting and perhaps useful parallels between the multisubunit ACCs of plants and those of bacteria. Plants contain two types of ACC, a polyfunctional protein where all four enzymatic components are concatenated into a single polypeptide and multisubunit (also called heteromeric) enzymes resembling those of bacteria. The heteromeric enzymes which are found only in plastids (such as chloroplasts) can best be studied in Arabidopsis and a few other plants that are not polyploid. The AccA, AccB, AccC, and AccD proteins resemble the bacterial proteins (probably because chloroplasts began as cyanobacteria) and form a complex that has ACC activity in vitro (68). The active heteromeric complex is thought to have two AccBs per AccC, but the situation is complicated by two accB genes that encode somewhat different proteins plus three biotin attachment domain-containing proteins (BADCs) that resemble AccB proteins but which cannot be biotinylated (69, 70). The BADCs have generally been considered negative regulators of ACC activity that act by taking the place of AccB subunits (69, 70). However, recently the BADCs have been ascribed a role in assembly of the active heteromeric complex (71). It is interesting that in most flowering plants, one of the subunits, AccD, is encoded by the chloroplast genome whereas the other subunits are encoded with chloroplast-targeting sequences by nuclear genes (72). However, more primitive plants such as some algae encode several ACC subunits in their chloroplast genomes and other plants have moved AccD to the nuclear genome (73, 74). The diverse locations of subunit genes seem likely to further complicate assembly of a stoichiometric ACC complex.

Finally, as mentioned above, plants have a eukaryotic single-chain ACC in the cytosol and the grasses (maize and wheat) also have a single-chain ACC in the plastids (75). The plant single-chain ACC enzymes are targets of various herbicides (76). Several very informative high-resolution structures of plant, yeast, and mammalian single-chain ACCs have been obtained despite their high molecular weights (76).

CONCLUSIONS

The structure of an intact fully active ACC complex is the “golden fleece” of the bacterial multisubunit ACCs. The most promising approach to obtain this goal seems likely to be cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Cryo-EM is a rapidly developing field that avoids the need for crystallization and is well suited to obtain structures of macromolecular complexes (77). Resolution as low as 2 Å can be obtained, with resolutions of 3 to 4 Å becoming routine. The major bottleneck is sample preparation, which essentially consists of keeping the complex intact on the EM grid. Despite its known instability, efforts should be made with the E. coli ACC complex because of the wealth of biochemical, physiological, and genetic information available. Moreover, the crystal structures of all four proteins are known (excepting the N-terminal half of AccB) which would be very useful in interpreting and validating the cryo-EM structures obtained. It may be possible to assemble and preserve the unstable complex by mixing the four proteins at the high concentrations with the stoichiometry used for assay of overall ACC activity (25) followed by rapid freezing. Another possibility is mild cross-linking using a general cross-linking molecule. With any cross-linking approach there is always the potential to induce artifacts caused by chemical fixation. However, the cross-links should be randomly dispersed throughout the molecular assembly, and thus, hopefully, these would be averaged out during image analysis.

Another approach would be to switch to a bacterium reported to make stable ACC complexes. Fall (23) reported a salt-stabilized ACC complex in partially purified cell extracts of Pseudomonas citronellolis. Hence, pseudomonad ACC seems worth consideration. Unfortunately, the genome sequence of the strain used by Fall is unknown. However, the acc genes are very well conserved in pseudomonads, so this may not be a hinderance. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 ACC proteins are 70% identical to those of E. coli, except AccB, which is 64% identical. However, the P. aeruginosa PAO AccB functionally complements the E. coli accB(Ts) allele (78). A difficulty may be the high salt concentration (0.4 M ammonium sulfate) reported to be needed (23) for complex stabilization, which could complicate cryogenic freezing of the samples.

Another bacterium reported to have a stable ACC complex is Helicobacter pylori (79), although it is unclear which strain was studied. However, the H. pylori ACC proteins are well conserved (>95%), so strain differences seem unlikely to be problematic. All of the H. pylori ACC proteins except AccB are about 50% identical to the E. coli proteins. Surprisingly, H. pylori AccB is only 31% identical to the E. coli protein, and hence it would be interesting to test its ability to complement an E. coli accB(Ts) strain. The possibility of a stable H. pylori ACC complex may deserve further investigation.

Finally, the question of how ACC stoichiometry is determined in E. coli remains largely unanswered. For example, the accA and accD genes are located halfway around the circular chromosome from one another. The accA promoters lie within the coding sequence of dnaE (polC), a gene essential for chromosome replication, and accD is the first gene of an operon containing genes unrelated to lipid metabolism. E. coli is not alone in this seemingly perverse accA-accD chromosomal gene arrangement; it is also found in P. aeruginosa and other pseudomonads. Why not have an accD-accA operon as found in Staphylococcus aureus and B. subtilis? The accB-accC operon found in many diverse bacteria (e.g., E. coli, B. subtilis, P. aeruginosa) accounts for the stoichiometry of those two subunits, but how is synthesis of these subunits coordinated with AccA and AccD synthesis? A number of transcription factors seem to be involved, but how overall coordination is achieved remains obscure. In other bacteria (e.g., Enterococcus faecalis and Clostridium acetobutylicum), the stoichiometry problem is solved using very large operons which contain all four acc genes together with most of the fatty acid synthesis genes. The locations of the accA and accD genes on the E. coli fit nicely a proposal by Zipkas and Riley (80) that an early step in E. coli evolution involved a total genome duplication that placed biochemically related pairs of genes 180° apart on the genome. The accA and accD genes are located at 0.21 and 2.4 Mbp of the 4.6-Mbp chromosome, and the protein products have blocks of 50% similarity and ∼25% identity in the central halves of the two proteins. Moreover, the two subunits have structurally equivalent overall folds, suggesting duplication and divergence of a single ancestral CT subunit gene (21). Hence, it seems possible that the need for a number of transcription factors is the consequence of genome duplication followed by retooling of one of the copies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Cited work from this laboratory and preparation of this review were supported by grant AI15650 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guchhait RB, Polakis SE, Dimroth P, Stoll E, Moss J, Lane MD. 1974. Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase system of Escherichia coli. Purification and properties of the biotin carboxylase, carboxyltransferase, and carboxyl carrier protein components. J Biol Chem 249:6633–6645. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimroth P, Guchhait RB, Stoll E, Lane MD. 1970. Enzymatic carboxylation of biotin: molecular and catalytic properties of a component enzyme of acetyl CoA carboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 67:1353–1360. 10.1073/pnas.67.3.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polakis SE, Guchhait RB, Zwergel EE, Lane MD, Cooper TG. 1974. Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase system of Escherichia coli. Studies on the mechanisms of the biotin carboxylase- and carboxyltransferase-catalyzed reactions. J Biol Chem 249:6657–6667. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guchhait RB, Polakis SE, Hollis D, Fenselau C, Lane MD. 1974. Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase system of Escherichia coli. Site of carboxylation of biotin and enzymatic reactivity of 1’-N-(ureido)-carboxybiotin derivatives. J Biol Chem 249:6646–6656. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fall RR, Vagelos PR. 1972. Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase. Molecular forms and subunit composition of biotin carboxyl carrier protein. J Biol Chem 247:8005–8015. 10.1016/S0021-9258(20)81801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberts AW, Nervi AM, Vagelos PR. 1969. Acetyl CoA carboxylase, II. Demonstration of biotin-protein and biotin carboxylase subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 63:1319–1326. 10.1073/pnas.63.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alberts AW, Gordon SG, Vagelos PR. 1971. Acetyl CoA carboxylase: the purified transcarboxylase component. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 68:1259–1263. 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberts AW, Vagelos PR. 1968. Acetyl CoA carboxylase. I. Requirement for two protein fractions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 59:561–568. 10.1073/pnas.59.2.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li SJ, Cronan JE. 1992. The genes encoding the two carboxyltransferase subunits of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem 267:16841–16847. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)41860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alix JH. 1989. A rapid procedure for cloning genes from lambda libraries by complementation of E. coli defective mutants: application to the fabE region of the E. coli chromosome. DNA 8:779–789. 10.1089/dna.1989.8.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li SJ, Cronan JE. 1992. The gene encoding the biotin carboxylase subunit of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem 267:855–863. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)48362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nenortas E, Beckett D. 1996. Purification and characterization of intact and truncated forms of the Escherichia coli biotin carboxyl carrier subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem 271:7559–7567. 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronan JE, Waldrop GL. 2002. Multi-subunit acetyl-CoA carboxylases. Prog Lipid Res 41:407–435. 10.1016/S0163-7827(02)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi-Rhee E, Cronan JE. 2003. The biotin carboxylase-biotin carboxyl carrier protein complex of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem 278:30806–30812. 10.1074/jbc.M302507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yates JR, Ruse CI, Nakorchevsky A. 2009. Proteomics by mass spectrometry: approaches, advances, and applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 11:49–79. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li SJ, Cronan JE. 1993. Growth rate regulation of Escherichia coli acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase, which catalyzes the first committed step of lipid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol 175:332–340. 10.1128/jb.175.2.332-340.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li GW, Burkhardt D, Gross C, Weissman JS. 2014. Quantifying absolute protein synthesis rates reveals principles underlying allocation of cellular resources. Cell 157:624–635. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Studier FW, Moffatt BA. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol 189:113–130. 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldrop GL, Rayment I, Holden HM. 1994. Three-dimensional structure of the biotin carboxylase subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochemistry 33:10249–10256. 10.1021/bi00200a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilder P, Lightle S, Bainbridge G, Ohren J, Finzel B, Sun F, Holley S, Al-Kassim L, Spessard C, Melnick M, Newcomer M, Waldrop GL. 2006. The structure of the carboxyltransferase component of acetyl-CoA carboxylase reveals a zinc-binding motif unique to the bacterial enzyme. Biochemistry 45:1712–1722. 10.1021/bi0520479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broussard TC, Price AE, Laborde SM, Waldrop GL. 2013. Complex formation and regulation of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochemistry 52:3346–3357. 10.1021/bi4000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fall RR. 1976. Stabilization of an acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase complex from Pseudomonas citronellolis. Biochim Biophys Acta 450:475–480. 10.1016/0005-2760(76)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cronan JE. 2001. The biotinyl domain of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Evidence that the “thumb” structure is essential and that the domain functions as a dimer. J Biol Chem 276:37355–37364. 10.1074/jbc.M106353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soriano A, Radice AD, Herbitter AH, Langsdorf EF, Stafford JM, Chan S, Wang S, Liu YH, Black TA. 2006. Escherichia coli acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase: characterization and development of a high-throughput assay. Anal Biochem 349:268–276. 10.1016/j.ab.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broussard TC, Kobe MJ, Pakhomova S, Neau DB, Price AE, Champion TS, Waldrop GL. 2013. The three-dimensional structure of the biotin carboxylase-biotin carboxyl carrier protein complex of E. coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Structure 21:650–657. 10.1016/j.str.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studier FW, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ, Dubendorff JW. 1990. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol 185:60–89. 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Studier FW. 2018. T7 expression systems for inducible production of proteins from cloned genes in E. coli. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 124:e63. 10.1002/cpmb.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman-Smith A, Turner DL, Cronan JE, Morris TW, Wallace JC. 1994. Expression, biotinylation and purification of a biotin-domain peptide from the biotin carboxy carrier protein of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochem J 302:881–887. 10.1042/bj3020881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alves J, Westling L, Peters EC, Harris JL, Trauger JW. 2011. Cloning, expression, and enzymatic activity of Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylases. Anal Biochem 417:103–111. 10.1016/j.ab.2011.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimroth P, Jockel P, Schmid M. 2001. Coupling mechanism of the oxaloacetate decarboxylase Na(+) pump. Biochim Biophys Acta 1505:1–14. 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Hamid AM, Cronan JE. 2007. Coordinate expression of the acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase genes, accB and accC, is necessary for normal regulation of biotin synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 189:369–376. 10.1128/JB.01373-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanchard CZ, Chapman-Smith A, Wallace JC, Waldrop GL. 1999. The biotin domain peptide from the biotin carboxyl carrier protein of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase causes a marked increase in the catalytic efficiency of biotin carboxylase and carboxyltransferase relative to free biotin. J Biol Chem 274:31767–31769. 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levin-Karp A, Barenholz U, Bareia T, Dayagi M, Zelcbuch L, Antonovsky N, Noor E, Milo R. 2013. Quantifying translational coupling in E. coli synthetic operons using RBS modulation and fluorescent reporters. ACS Synth Biol 2:327–336. 10.1021/sb400002n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burkhardt DH, Rouskin S, Zhang Y, Li GW, Weissman JS, Gross CA. 2017. Operon mRNAs are organized into ORF-centric structures that predict translation efficiency. Elife 6:e22037. 10.7554/eLife.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karow M, Fayet O, Georgopoulos C. 1992. The lethal phenotype caused by null mutations in the Escherichia coli htrB gene is suppressed by mutations in the accBC operon, encoding two subunits of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase. J Bacteriol 174:7407–7418. 10.1128/jb.174.22.7407-7418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James ES, Cronan JE. 2004. Expression of two Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase subunits is autoregulated. J Biol Chem 279:2520–2527. 10.1074/jbc.M311584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans A, Ribble W, Schexnaydre E, Waldrop GL. 2017. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase from Escherichia coli exhibits a pronounced hysteresis when inhibited by palmitoyl-acyl carrier protein. Arch Biochem Biophys 636:100–109. 10.1016/j.abb.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Queiroz MS, Waldrop GL. 2007. Modeling and numerical simulation of biotin carboxylase kinetics: implications for half-sites reactivity. J Theor Biol 246:167–175. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mochalkin I, Miller JR, Evdokimov A, Lightle S, Yan C, Stover CK, Waldrop GL. 2008. Structural evidence for substrate-induced synergism and half-sites reactivity in biotin carboxylase. Protein Sci 17:1706–1718. 10.1110/ps.035584.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janiyani K, Bordelon T, Waldrop GL, Cronan JE. 2001. Function of Escherichia coli biotin carboxylase requires catalytic activity of both subunits of the homodimer. J Biol Chem 276:29864–29870. 10.1074/jbc.M104102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis MS, Cronan JE. 2001. Inhibition of Escherichia coli acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase by acyl-acyl carrier protein. J Bacteriol 183:1499–1503. 10.1128/JB.183.4.1499-1503.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cronan JE. 1988. Expression of the biotin biosynthetic operon of Escherichia coli is regulated by the rate of protein biotination. J Biol Chem 263:10332–10336. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)81520-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chapman-Smith A, Cronan JE. 1999. The enzymatic biotinylation of proteins: a post-translational modification of exceptional specificity. Trends Biochem Sci 24:359–363. 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henke SK, Cronan JE. 2016. The Staphylococcus aureus group II biotin protein ligase BirA is an effective regulator of biotin operon transcription and requires the DNA binding domain for full enzymatic activity. Mol Microbiol 102:417–429. 10.1111/mmi.13470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henke SK, Cronan JE. 2014. Successful conversion of the Bacillus subtilis BirA Group II biotin protein ligase into a Group I ligase. PLoS One 9:e96757. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cronan JE. 1989. The E. coli bio operon: transcriptional repression by an essential protein modification enzyme. Cell 58:427–429. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sirithanakorn C, Cronan JE. 2021. Biotin, a universal and essential cofactor: synthesis, ligation and regulation. FEMS Microbiol Rev fuab003. 10.1093/femsre/fuab003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beckett D. 2007. Biotin sensing: universal influence of biotin status on transcription. Annu Rev Genet 41:443–464. 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.170450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feria Bourrellier AB, Valot B, Guillot A, Ambard-Bretteville F, Vidal J, Hodges M. 2010. Chloroplast acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity is 2-oxoglutarate-regulated by interaction of PII with the biotin carboxyl carrier subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:502–507. 10.1073/pnas.0910097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerhardt EC, Rodrigues TE, Müller-Santos M, Pedrosa FO, Souza EM, Forchhammer K, Huergo LF. 2015. The bacterial signal transduction protein GlnB regulates the committed step in fatty acid biosynthesis by acting as a dissociable regulatory subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Mol Microbiol 95:1025–1035. 10.1111/mmi.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodrigues TE, Gerhardt EC, Oliveira MA, Chubatsu LS, Pedrosa FO, Souza EM, Souza GA, Müller-Santos M, Huergo LF. 2014. Search for novel targets of the PII signal transduction protein in bacteria identifies the BCCP component of acetyl-CoA carboxylase as a PII binding partner. Mol Microbiol 91:751–761. 10.1111/mmi.12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leigh JA, Dodsworth JA. 2007. Nitrogen regulation in bacteria and archaea. Annu Rev Microbiol 61:349–377. 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hauf W, Schmid K, Gerhardt EC, Huergo LF, Forchhammer K. 2016. Interaction of the nitrogen regulatory protein Glnb (PII) with biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP) controls acetyl-CoA levels in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Front Microbiol 7:1700. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodrigues TE, Sassaki GL, Valdameri G, Pedrosa FO, Souza EM, Huergo LF. 2019. Fatty acid biosynthesis is enhanced in Escherichia coli strains with deletion in genes encoding the PII signaling proteins. Arch Microbiol 201:209–214. 10.1007/s00203-018-1603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polakis SE, Guchhait RB, Lane MD. 1973. Stringent control of fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. Possible regulation of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase by ppGpp. J Biol Chem 248:7957–7966. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)43280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heath RJ, Jackowski S, Rock CO. 1994. Guanosine tetraphosphate inhibition of fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis in Escherichia coli is relieved by overexpression of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (plsB). J Biol Chem 269:26584–26590. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)47234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meades G, Benson BK, Grove A, Waldrop GL. 2010. A tale of two functions: enzymatic activity and translational repression by carboxyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res 38:1217–1227. 10.1093/nar/gkp1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saxena S, Myka KK, Washburn R, Costantino N, Court DL, Gottesman ME. 2018. Escherichia coli transcription factor NusG binds to 70S ribosomes. Mol Microbiol 108:495–504. 10.1111/mmi.13953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Artsimovitch I. 2018. Rebuilding the bridge between transcription and translation. Mol Microbiol 108:467–472. 10.1111/mmi.13964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mitra P, Ghosh G, Hafeezunnisa M, Sen R. 2017. Rho protein: roles and mechanisms. Annu Rev Microbiol 71:687–709. 10.1146/annurev-micro-030117-020432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith AC, Cronan JE. 2014. Evidence against translational repression by the carboxyltransferase component of Escherichia coli acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase. J Bacteriol 196:3768–3775. 10.1128/JB.02091-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cronan JE. 2020. The Escherichia coli FadR transcription factor: too much of a good thing. Mol Microbiol 10.1111/mmi.14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cronan JE, Subrahmanyam S. 1998. FadR, transcriptional co-ordination of metabolic expediency. Mol Microbiol 29:937–943. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.My L, Rekoske B, Lemke JJ, Viala JP, Gourse RL, Bouveret E. 2013. Transcription of the Escherichia coli fatty acid synthesis operon fabHDG is directly activated by FadR and inhibited by ppGpp. J Bacteriol 195:3784–3795. 10.1128/JB.00384-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.My L, Ghandour Achkar N, Viala JP, Bouveret E. 2015. Reassessment of the genetic regulation of fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli: global positive control by the dual functional regulator FadR. J Bacteriol 197:1862–1872. 10.1128/JB.00064-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vadia S, Tse JL, Lucena R, Yang Z, Kellogg DR, Wang JD, Levin PA. 2017. Fatty acid availability sets cell envelope capacity and dictates microbial cell size. Curr Biol 27:1757–1767.e5. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salie MJ, Thelen JJ. 2016. Regulation and structure of the heteromeric acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861:1207–1213. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye Y, Fulcher YG, Sliman DJ, Day MT, Schroeder MJ, Koppisetti RK, Bates PD, Thelen JJ, Van Doren SR. 2020. The BADC and BCCP subunits of chloroplast acetyl-CoA carboxylase sense the pH changes of the light-dark cycle. J Biol Chem 295:9901–9916. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.012877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu X-H, Cai Y, Keereetaweep J, Wei K, Chai J, Deng E, Liu H, Shanklin J. 2021. Biotin attachment domain-containing proteins mediate hydroxy fatty acid-dependent inhibition of acetyl CoA carboxylase. Plant Physiol 185:892–901. 10.1093/plphys/kiaa109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shivaiah KK, Ding G, Upton B, Nikolau BJ. 2020. Non-catalytic subunits facilitate quaternary organization of plastidic acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Plant Physiol 182:756–775. 10.1104/pp.19.01246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li SJ, Cronan JE. 1992. Putative zinc finger protein encoded by a conserved chloroplast gene is very likely a subunit of a biotin-dependent carboxylase. Plant Mol Biol 20:759–761. 10.1007/BF00027147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sasaki Y, Konishi T, Nagano Y. 1995. The compartmentation of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase in plants. Plant Physiol 108:445–449. 10.1104/pp.108.2.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huerlimann R, Heimann K. 2013. Comprehensive guide to acetyl-carboxylases in algae. Crit Rev Biotechnol 33:49–65. 10.3109/07388551.2012.668671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gornicki P, Faris J, King I, Podkowinski J, Gill B, Haselkorn R. 1997. Plastid-localized acetyl-CoA carboxylase of bread wheat is encoded by a single gene on each of the three ancestral chromosome sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:14179–14184. 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tong L. 2017. Striking diversity in holoenzyme architecture and extensive conformational variability in biotin-dependent carboxylases. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 109:161–194. 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lyumkis D. 2019. Challenges and opportunities in cryo-EM single-particle analysis. J Biol Chem 294:5181–5197. 10.1074/jbc.REV118.005602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Best EA, Knauf VC. 1993. Organization and nucleotide sequences of the genes encoding the biotin carboxyl carrier protein and biotin carboxylase protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase. J Bacteriol 175:6881–6889. 10.1128/jb.175.21.6881-6889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burns BP, Hazell SL, Mendz GL. 1995. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity in Helicobacter pylori and the requirement of increased CO2 for growth. Microbiology 141:3113–3118. 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zipkas D, Riley M. 1975. Proposal concerning mechanism of evolution of the genome of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 72:1354–1358. 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Athappilly FK, Hendrickson WA. 1995. Structure of the biotinyl domain of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase determined by MAD phasing. Structure 3:1407–1419. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yao X, Wei D, Soden C, Summers MF, Beckett D. 1997. Structure of the carboxy-terminal fragment of the apo-biotin carboxyl carrier subunit of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochemistry 36:15089–15100. 10.1021/bi971485f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roberts EL, Shu N, Howard MJ, Broadhurst RW, Chapman-Smith A, Wallace JC, Morris T, Cronan JE, Perham RN. 1999. Solution structures of apo and holo biotinyl domains from acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase of Escherichia coli determined by triple-resonance nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry 38:5045–5053. 10.1021/bi982466o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Solbiati J, Chapman-Smith A, Cronan JE. 2002. Stabilization of the biotinoyl domain of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase by interactions between the attached biotin and the protruding “thumb” structure. J Biol Chem 277:21604–21609. 10.1074/jbc.M201928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chapman-Smith A, Forbes BE, Wallace JC, Cronan JE. 1997. Covalent modification of an exposed surface turn alters the global conformation of the biotin carrier domain of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem 272:26017–26022. 10.1074/jbc.272.41.26017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thoden JB, Blanchard CZ, Holden HM, Waldrop GL. 2000. Movement of the biotin carboxylase B-domain as a result of ATP binding. J Biol Chem 275:16183–16190. 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lu P, Vogel C, Wang R, Yao X, Marcotte EM. 2007. Absolute protein expression profiling estimates the relative contributions of transcriptional and translational regulation. Nat Biotechnol 25:117–124. 10.1038/nbt1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuntumalla S, Braisted JC, Huang ST, Parmar PP, Clark DJ, Alami H, Zhang Q, Donohue-Rolfe A, Tzipori S, Fleischmann RD, Peterson SN, Pieper R. 2009. Comparison of two label-free global quantitation methods, APEX and 2D gel electrophoresis, applied to the Shigella dysenteriae proteome. Proteome Sci 7:22. 10.1186/1477-5956-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wiśniewski JR, Rakus D. 2014. Multi-enzyme digestion FASP and the ‘Total Protein Approach’-based absolute quantification of the Escherichia coli proteome. J Proteomics 109:322–331. 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhao J, Zhang H, Qin B, Nikolay R, He QY, Spahn CMT, Zhang G. 2019. Multifaceted stoichiometry control of bacterial operons revealed by deep proteome quantification. Front Genet 10:473. 10.3389/fgene.2019.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]