Abstract

Biscuits are ready-to-eat foods that are traditionally prepared mainly with wheat flour, fat, and sugar. Recently, biscuits’ technologies have been rapidly developed to improve their nutritional properties. This study aimed to determine the strategies of improving the nutritional quality of biscuits and the potential health benefits associated with them. A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted, including articles on biscuits improved by technological processes and raw materials variation. Studies were searched from Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science published between 1997 and 2020, in English and French. The meta-analysis was performed using RStudio software, version 4.0.4 to classify the biscuits. One hundred and seven eligible articles were identified. Rice, pea, potato, sorghum, buckwheat, and flaxseed flours were respectively the most found substitutes to wheat flour. But the meta-analysis shown that the copra and foxtail millet biscuit fortified with amaranth, the wheat biscuits fortified with okra, and rice biscuits fortified with soybeans had a high protein content. These biscuits therefore have a potential to be used as complementary foods. The substitution of sugar and fat by several substitutes lead to a decrease in carbohydrates, fat, and energy value. It has also brought about an increase in other nutrients such as dietary fiber, proteins/amino acids, fatty acids, and phenolic compounds. Among the sugar and fat substitutes, stevia and inulin were respectively the most used. Regarding the use of biscuits in clinical trials, they were mainly used for addressing micronutrient deficiency and for weight loss.

Keywords: Biscuit, Technology, Nutrition, Health benefits

Introduction

Many efforts have been made to develop food products that can improve people’s health (Coutinho de Moura et al. 2014; Galanakis 2020; Granato et al. 2010). In developing countries, while overweight/obesity is increasing in all age groups, undernutrition persists and coexists with obesity and the burden of diet-related diseases (World Health Organization 2021). Furthermore, recent outbreaks of infectious diseases, such as malaria, Ebola virus disease, HIV pandemic, and the recent COVID-19 crisis emphasize the need to adopt healthy diets (Galanakis 2020). As a result, many health organizations have been incentivized to the development and consumption of improved food, such as food enriched with functional constituents (French Ministry of Health 2006; Hercberg et al. 2008; World Health Organization 2015). For this purpose, several popular or traditional foods have been used as vehicles in fortification strategies.

Popular foods are effective vehicles for nutrient incorporation and are thus targeted by a growing and increasingly demanding market for the management of health disorders (Granato et al. 2010). Among these foods, biscuits show potential as improved food (Nogueira & Steel 2018) to meet nutritional needs or prevent diet-related illnesses. Biscuits offer several possibilities for the management of human nutrition-related disorders. They are widely consumed as snacks or as complement to other foods. They present varied forms and pleasant flavors, have long shelf lives, and provide convenience (Agama-Acevedo et al. 2012; Manley 2011). Therefore, the production and consumption of biscuits have considerably increased worldwide (Canalis et al. 2017). For products with the fast-moving consumer goods category, the biscuit market is among the leading ones (Apeda agri exchange 2020). The biscuit market reached $76.385 billion at the end of 2017 and expected to reach USD 121 billion by 2021 and USD 164 billion by 2024 at compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.7 and 5.08%, respectively (Apeda agri exchange 2020). The highest per capita consumption of biscuits in the world is approximately 13 kg per year (Canalis et al. 2017). The wide consumption of biscuit makes it an ideal product for fortification (Kadam & Prabhasankar 2010). However, some biscuits are even used as part of nutritional strategies to tackle several chronic and nutrition-related diseases, such as nutrient deficiencies, diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers (Canalis et al. 2017; Singh & Kumar 2017; van Stuijvenberg et al. 2001). Innovations in biscuit technologies and recipes have resulted in a wide range of biscuit products, both the forms and nutritional properties (Denis 2011; Filipčev et al. 2014; Swapna & Jayaraj Rao 2016). Biscuits have many functional forms and can be enriched with mineral and vitamin complexes (MVC) or nutrient-rich complementary ingredients, and formulated for infants, children, the elderly and those with special needs such as the obese and diabetics (Davidson 2019). The fortification ability of biscuits and their high consumer acceptance have led to them receiving more attention for formulating functional foods or nutraceuticals. Several clinical trials have also been carried out on the efficacy of improved biscuits against illnesses and prevention of chronic and nutrition-related diseases (Kriengsinyos et al. 2015; Kekalih et al. 2019; Buffière et al. 2020). Compared to the large number of biscuits currently available, the number of research studies examining improved biscuits and their use in clinical trials is quite limited. Therefore, this paper reviews the different improved biscuits and their use in clinical trials against illnesses and risk of chronic diseases such as malnutrition, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cancer, obesity, low HDL cholesterol, high triglyceride level, etc.

Methods

Search strategy

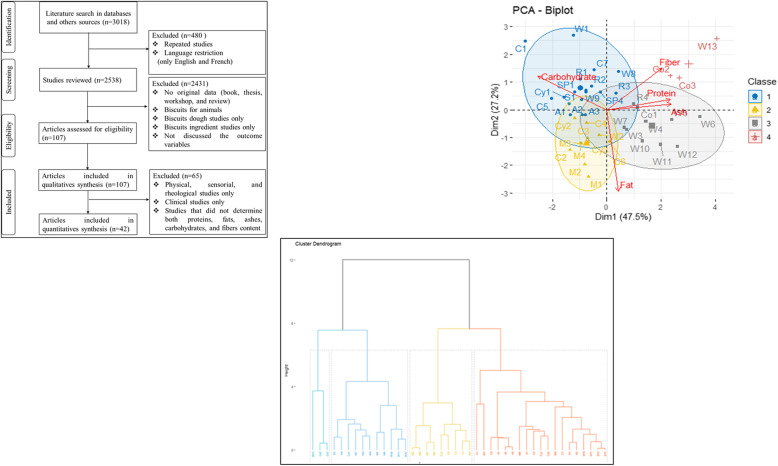

At first, this study searched in many databases as Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science with keywords. These keywords are: Biscuit OR Cookie OR Cracker AND Improved quality, Biscuit OR Cookie OR Cracker AND High quality, Improved Biscuit OR Cookie OR Cracker, High quality Biscuit OR Cookie OR Cracker, Biscuit OR Cookie OR Cracker AND Health benefits, Biscuit OR Cookie OR Cracker AND Clinical trial, Biscuit OR Cookie OR Cracker AND Trial. Secondly, references of all identified articles were searched to get additional studies. Figure 1 shows the articles selection procedure and information used in this study.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of screening process

Inclusion criteria

Studies with the following criteria were eligible for inclusion: 1) studies that have investigated the effect of total or partial substitution of wheat flour; 2) studies that have investigated the effect of substitution or the reduction of sugar or fat for the production of biscuits; 3) studies that have investigated novelties in the processing of improved biscuits; 4) studies that have investigated the use of improved biscuits in clinical trials.

The term “biscuit” derives from the Latin word biscoctus, which means twice-cooked/baked (Chavan et al. 2016). The origin of biscuit dates back to Roman times to resolve food preservation (Chavan et al. 2016). In baking, the word “biscuit” includes several groups of products. It is called “biscuit” in the United Kingdom and in France, “cookie” and “cracker” in the United States, and “scone” in New Zealand (Chavan et al. 2016; Denis 2011). For other authors, biscuits are termed interchangeably with cookies in the United Kingdom and Asia (Cauvain & Young 2008). However, some differences can be noted between the products. Biscuits are generally made from short dough, which is undeveloped and lacks extensibility (Xu et al. 2020) while cookies are made from soft dough, which has high sugar, high fat, and low moisture content (Delcour & Hoseney 2010). Cracker, for instance, is traditionally made from soft dough and is a thin and crisp product baked from unsweetened and unleavened dough (Xu et al. 2020). In this paper, the term biscuit is used for biscuits, cookies, and cracker.

Exclusion criteria

Letters, comments, communications, reviews, thesis, and animal studies were excluded. Also, excluded were articles published in languages other than English and French, citations with no abstracts and/or full texts, duplicate studies, and articles focusing solely on biscuits ingredients and dough studies. Furthermore, for the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis), the articles reporting only on physical, sensorial, and rheological properties, clinical trials, and those that did not determine jointly proteins, fats, ashes, carbohydrates, and fibers contents were excluded.

Synthesis of findings

The included articles were analysed qualitatively using a thematic analysis approach. Then, all articles were synthesized by systematic reading.

Results

Study characteristics

In our initial search, we found 3018 articles, of which 480 were identified as repeated studies or language restriction (only English and French) and were excluded. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 2431 articles were also excluded for the following reasons: 1) no original data (book, thesis, workshop, and review); 2) biscuits for animals; 3) biscuit ingredients studies only; and 4) biscuits dough studies only. After this, there were 107 articles left to include in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1).

For the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis), 65 articles were excluded due to the following reasons: 1) physical, sensorial, and rheological studies only; 2) clinical trials studies only; and 3) studies that did not determine jointly proteins, fats, ashes, carbohydrates, and fibers contents. Finally, 42 articles were included (Fig. 1).

One hundred and seven articles were identified for the systematic review, from which sixty-nine were based on partial or total substitution of wheat flour by other flours (Table 1). From the sixty-nine substituted wheat flour biscuits, twenty-nine were based on total substitution of wheat flour. Besides, 20/107 and 11/107 dealt with, respectively, the high amount of sugar and fat in biscuits (Tables 1 and 2). Finally, 19 / 107 articles were based on the use of biscuits in clinical trials (Table 3).

Table 1.

Improved materials used to substitute wheat flour in biscuit production

| Product added | Improvement elements | Substitution level (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buckwheat | Processing properties, sensory, and textural characteristics, protein content, and gluten-free biscuits | 50–100 | Sedej et al. 2011; Torbica et al. 2012; Hadnađev et al. 2013; Mancebo et al. 2015; Kaur et al. 2015 |

| Sorghum | Dietary fiber and low calorie; Fat, protein, ash, and calorific values as compared to wheat biscuits | 25–45, 50, and 100 | Okpala & Okoli 2011; Banerjee et al. 2014; Rai et al. 2014; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016, 2017 |

| Maize | Gluten-free biscuits | 100 | Rai et al. 2014; Mancebo et al. 2015 |

| Rice | Processing properties, sensory, and textural characteristics, gluten-free biscuits | 50–100 | Ceesay et al. 1997; Torbica et al. 2012; Hadnađev et al. 2013; Radočaj et al. 2014; Rai et al. 2014; Mancebo et al. 2015; Benkadri et al. 2018; Sulieman et al. 2019 |

| Pearl millet | Fat, protein, ash, and calorific values as compared to wheat biscuits | 100 | Rai et al. 2014 |

| Foxtail millet flour | Low phytates and tannins, increased polyphenols | 9 | Singh & Kumar 2017 |

| Copra | Fiber and protein contents | 51 | Singh et al. Singh & Kumar 2017 |

| Pea | Protein, fat, iron, and crude fiber contents | 5–100 | (Adeola & Ohizua 2018, Benkadri et al. 2018 Chinma et al. 2011, Dhankhar et al. 2019, Han et al. 2010, Okpala & Okoli 2011, Silky & Tiwari 2014, Zucco et al. 2011) |

| Bean | Physical and nutritional characteristics | 25, 50, 75, and 100 | Han et al. 2010; Zucco et al. 2011 |

| Lentil | Physical and nutritional characteristics | 100 | Han et al. 2010; Zucco et al. 2011 |

| Potato | Protein, fat, minerals, crude fiber, staling, flavor, ash, and sugar | 10, 14, 16, 18–100 | (Abou-Zaid & Elbandy 2014; Onabanjo & Ighere 2014; Adeyeye & Akingbala 2015; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016; Adeola & Ohizua 2018; Sulieman et al. 2019) |

| Cheese | Digestible source of fat and protein and rich source of vitamin A, B2 and B12 and highly bioavailable minerals as calcium and zinc | 30, 40, and 50 | Swapna & Jayaraj Rao 2016 |

| Date powder | Fiber | 10, 20, 30, and 40 | Dhankhar et al. 2019 |

| Soy | Protein, anti-nutrients, amino acids and vitamins profile and sensory evaluation | 5, 10, 15, and 20 | Hu et al. 2013, Loo et al. 2017; Ghoshal & Kaushik 2020, Adeyeye 2020 |

| Flaxseed | ω-3 (α-linolenic acid), dietary soluble and insoluble fibers and lignans | 5, 12, 15, 30, 50, and 75 | Hassan et al. 2012; Coutinho de Moura et al. 2014; Austria et al. 2016; Omran et al. 2016; Kuang et al. 2020 |

| Almond | Bioactive components | – | Jung et al. 2018; Bowen et al. 2019; Pasqualone et al. 2020 |

| Groundnut | Energy, protein, calcium, and iron | – | Ceesay et al. 1997 |

| Fenugreek | Protein, lysine, dietary fiber, Ca, Fe, alkaloids, flavonoids, and saponins | 5, 10, and 15 | Hooda & Jood 2005 |

| Mushrooms | Protein, fiber, ash, fat, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, calcium, vitamin B3, vitamin C, texture, flavor, and sensory acceptability | 5, 10, 15, and 20 | Ayo et al. 2018; Biao et al. 2020 |

| Acha | Carbohydrate | 100 | Ayo et al. 2018 |

| Cocoyam | Carbohydrate | 100 | Okpala & Okoli 2011; Akujobi 2018 |

| Tigernut flour | Protein, magnesium, iron, zinc, vitamin E, vitamin A, and folic acid | 30, 50, 70, 80, 85, 90 and 95 | Chinma et al. 2011; Akujobi 2018 |

| Gums | Effect of gums addition on color, appearance and flavor and overall acceptability | 100 | Kaur et al. 2015 |

| Multi-micronutrients (Iron, zinc, iodine, and vitamin A) | Iron, zinc, iodine, and vitamin A content | – | Nga et al. 2009, 2011; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016 |

| Amaranth flours | Amino acid profile and high bioavailability of protein | 13, 20, and 40 | De la Barca et al. 2010; Singh & Kumar 2017 |

| Fish and crustacean | Lysine, amino acids | 3, 5, and 6 | Ibrahim 2009; Abou-Zaid & Elbandy 2014 |

| Grape (skin and seeds) | Proteins, ash, lipids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and phenolic compounds (tannins, phenolic acids, anthocyanins, and resveratrol) | 15 | Karnopp et al. 2015; Kuchtová et al. 2016, 2018 |

| Moringa | Carotenoid, protein, and dietary fiber | 5, 10, and 15 | Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016, 2017 |

| Spirulina | Carotenoid | 4, 6, and 8 | Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016, 2017 |

| Hemp flour | Protein, crude fibers, minerals, and essential fatty acids | 10, 20, 30, and 40 | Radočaj et al. 2014 |

| Okra powder | Protein, ash, and fiber | 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 | Akoja & Coker 2018 |

| Tea leaves | Protein, fiber, minerals, and antioxidant properties | 2.67, 2.02, 1.35, and 0.68 | Radočaj et al. 2014 |

| Mustard meal | Sensory quality maintained, nutritional and functional properties improved | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 | Hassan et al. 2012 |

| Barley meal | Sensory quality maintained, nutritional and functional properties improved | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 | Hassan et al. 2012 |

| Teff flour | Essential amino acids, iron, calcium, copper, zinc, aluminum, and barium | 10, 20, 40, and 100 | Coleman et al. 2013; Mancebo et al. 2015 |

| Oat (flour and bran) | Influence of different packaging on the storage period, fibers content | 100 | Serial et al. 2016; Swapna & Jayaraj Rao 2016; Lee & Kang 2018; Duta et al. 2019 |

| Inulin | Fibers content | – | Serial et al. 2016 |

| Whey protein | Dietary fiber, protein, lipids, carbohydrate, sugar and energy | 25 | Aggarwal et al. 2016, Hassanzadeh-Rostami et al. 2020 |

| Agaricus bisporus polysaccharide | Ash, protein, fat and total dietary fibers | 3, 6, and 9 | Sulieman et al. 2019 |

| Banana (flour and peel) | Phenolic compound, starch digestibility, and glycemic index | 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, and 50 | Ovando-Martinez et al. 2009; Agama-Acevedo et al. 2012; Arun et al. 2015; Adeola & Ohizua 2018 |

| Mango peel | Dietary fiber, polyphenols and carotenoids | 5, 7.5, 10, 15, and 20 | Ajila et al. 2008 |

| Fruit and vegetable residue | Fiber and mineral | 20, 25, and 35 | Ferreira et al. 2013 |

| Citrus (orange and lemon) by-products | Dietary fiber | 0, 5, 10, and 15 | Kohajdova et al. 2011 |

| Grapefruits by-products | Dietary fiber | 5, 10, and 15 | Kohajdova et al. 2013 |

| Watermelon rind powder | Dietary fiber, total phenolic content, glycemic index, and antioxidant activity | 10, 20, and 30 | Naknaen et al. 2016 |

| Sour cherry pomace | Total polyphenols, total anthocyanins, and antioxidant activity | 10 and 15 | Šaponjac et al. 2016 |

| Berries pomace | Linoleic acid and α -linolenic acid | 20 and 30 | Šarić et al. 2016 |

| Pomegranate peel | Protein, dietary fiber, minerals, antioxidant activity, and β-carotene content | 10 | Srivastava et al. 2014 |

| Apple pomace | Antioxidant properties, total dietary fiber, and minerals content | 3, 6, 9, 15, and 20 | Mir et al. 2015; Sudha et al. 2016 |

| Olive pomace | Polyphenols and fiber | – | Conterno et al. 2019 |

| Pomace of rowanberry, rosehip, blackcurrant, and elderberry | Dietary fiber, vitamins, and phenolic compounds | 20 | Tańska et al. 2016 |

| Pumpkin | Dietary fiber | 10 and 15 | Turksoy & Ozkaya 2011 |

| Carrot pomace | Dietary fiber | 10 and 15 | Turksoy & Ozkaya 2011 |

| Carob by-products (germ and seed peel) | Protein, fiber and antioxidant activity | Carob peel: 0–9; Carob germ: 0–18 | Martin-Diana et al. 2016 |

| Beet molasses | Biscuit spread, fracturability, and storability | 10–50 | Filipčev et al. 2014, 2015 |

| Glucomannan and xanthan | Fiber content | – | Jenkins et al. 2008 |

| Plant Stanol Ester | Phytosterols | – | Kriengsinyos et al. 2015 |

| Fructo-oligosaccharides | Fiber content | 20 | Tuohy et al. 2001 |

| Gum (guar and xanthan) | Technological properties, fiber content | 11 | Tuohy et al. 2001; Benkadri et al. 2018 |

Table 2.

Sugar substitutes and their potential effect on biscuit quality

| Sugar substitute | Nature | Sugar rate (%) | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maltitol and FOS-Sucralose | 100 | Aggarwal et al. 2016 | ||

| Raftilose | Oligofructose | 20 | Reduce sugar content | Gallagher et al. 2003 |

| Stevia | S. rebaudiana leaves | 0.06–0.08-0.1-0.14, 25, 50, 75, and 100 | High fiber content, angiotensin-converting enzyme and α-amylase inhibitory activity, and antioxidant effect | Vatankhah et al. 2015; Pourmohammadi et al. 2017; Góngora Salazar et al. 2018 |

| Erythritol | Sweetener | 25, 50, 75, and 100 | Partial replacement of sucrose with up to 50% erythritol had sensory and physical quality characteristics comparable with cookies prepared with 100% sucrose | Lin et al. 2010 |

| Arabinoxylan oligosaccharides | Complex carbohydrates | 30 | Reduction of sucrose and increase of fiber levels | Pareyt et al. 2011 |

| Isomalt | Polyol | 3, 6, 9, and 12 | Reduction of sucrose | Pourmohammadi et al. 2017 |

| Maltodextrin | Starch | 2.5–5–7.5-10 | Reduction of sucrose | Pourmohammadi et al. 2017 |

| Isomalt, maltodextrin, stevia | – | 6–2.5-0.06 | Biscuits were more comparable to one elaborate with sucrose, and with the highest acceptance level in sensory evaluations | Pourmohammadi et al. 2017 |

Table 3.

Shortening substitutes and their potential effect on biscuit quality

| Fat substitute | Nature | Substitution rate (%) | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inulin | Non-digestible dietary fiber | 20 and 25 | Textural and sensory properties maintained; Dietary fiber increased, weakened lubrication of biscuit dough, reduction of energy density | Rodríguez-García et al. 2013; Błońska et al. 2014; Banerjee et al. 2014; Krystyjan et al. 2015; Onacik-Gür et al. 2015; Canalis et al. 2017 |

| Rice starch | Complex carbohydrates | 20 | Native and modified rice starch effective | Lee & Puligundla 2016 |

| Corn fiber | Complex carbohydrates | 30 | Fat reduction and fiber fortification | Forker et al. 2012 |

| Lupine extract | Complex carbohydrates | 30 | Fat reduction and fiber fortification | Forker et al. 2012 |

| Wheat bran fibers | Plant fibers | 10, 20, and 30 | Texture of biscuits was greatly dependent on the texture of the dough | Erinc et al. 2018 |

| Candelilla wax-canola oil oleogels | Oil | 30–40 | Decrease of saturated fatty acids (63.4% → 32.3%) | Jang et al. 2015 |

| Puree of canned green peas | 75 | Sensory assessment | Romanchik-Cerpovicz et al. 2018 | |

| Lecithin | 3 | Lecithin (3%, sunflower based) achieved similar sensory quality as fat biscuit | Onacik-Gür et al. 2015 | |

| Maltodextrin | Complex carbohydrates | 50, 60, and 70 | Texture maintained, low-fat biscuit | Sudha et al. 2007; Chugh et al. 2013 |

| Guar gum | Complex carbohydrates | – | Low-fat biscuit | Chugh et al. 2013 |

| Polydextrose | Complex carbohydrates | 50, 60, and 70 | Texture maintained | Sudha et al. 2007, Aggarwal et al. 2016 |

| Red palm oil | Oil | – | β-carotene | van Stuijvenberg et al. 2001 |

| Goat fat | Oil | 100 | Functional and nutritional properties increased | Costa et al. 2019 |

| Flax oil | Oil | 100 | ω-3 fatty acids | Hassan et al. 2012 |

| Sunflower oil | Oil | 100 | Free of trans and low-saturated fats | Tarancon et al. 2013; Onacik-Gür et al. 2015 |

| Olive oil | Oil | 100 | Free of trans and low-saturated fats | Tarancón et al. Tarancon et al. 2013 |

Synthesis of improvement studies

A listing of materials used to improve the nutritional quality of biscuits is summarized in Table 1. They includes, mushroom (Biao et al. 2020; Jung & Joo 2010), banana flour (Ovando-Martinez et al. 2009), pigeon pea flour (Adeola & Ohizua 2018; Silky & Tiwari 2014), sweet potato (Adeola & Ohizua 2018; Adeyeye & Akingbala 2015; Onabanjo & Ighere 2014), cheese (Swapna & Jayaraj Rao 2016), tigernut (Chinma et al. 2011), flaxeed (Hassan et al. 2012), fenugreek seeds (Hooda & Jood 2005), grape (Karnopp et al. 2015; Kuchtová et al. 2016, 2018), fish and crustacean (Ibrahim 2009; Abou-Zaid and Elbandy 2014), hemp flour (Radočaj et al. 2014), and decaffeinated green tea leaves (Radočaj et al. 2014). In addition, several by-products such as germ, and peel (Martin-Diana et al. 2016) have been used in partial substitution of cereal flour in the formula of biscuit.

Among the 69 articles based on the substitution of flour that are included in this study, rice (Benkadri et al. 2018; Ceesay et al. 1997; Hadnađev et al 2013; Mancebo et al. 2015; Radočaj et al. 2014; Rai et al. 2014; Sulieman et al. 2019; Torbica et al. 2012), pea (Han et al. 2010; Chinma et al. 2011; Okpala & Okoli 2011; Zucco et al. 2011; Silky & Tiwari 2014; Adeola & Ohizua 2018; Benkadri et al. 2018; Dhankhar et al. 2019, potato (Abou-Zaid & Elbandy 2014; Onabanjo & Ighere 2014; Adeyeye & Akingbala 2015; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016; Adeola & Ohizua 2018; Sulieman et al. 2019), sorghum (Banerjee et al. 2014; Okpala & Okoli 2011; Rai et al. 2014; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016, 2017), buckwheat (Hadnađev et al. 2013; Kaur et al. 2015; Mancebo et al. 2015; Sedej et al. 2011; Torbica et al. 2012), and flaxseed (Hassan et al. 2012; Coutinho de Moura et al. 2014; Austria et al. 2016; Kuang et al. 2020; Omran et al. 2016) have received more attention (Table 1).

Quantitative synthesis

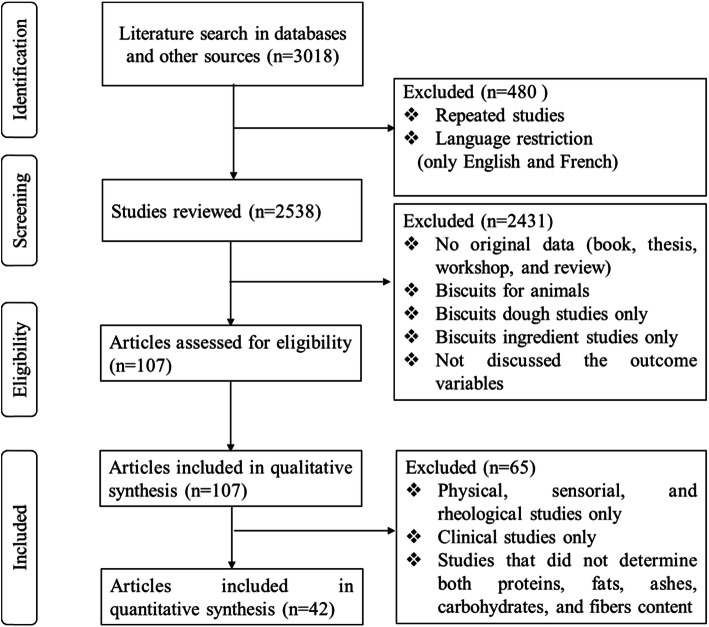

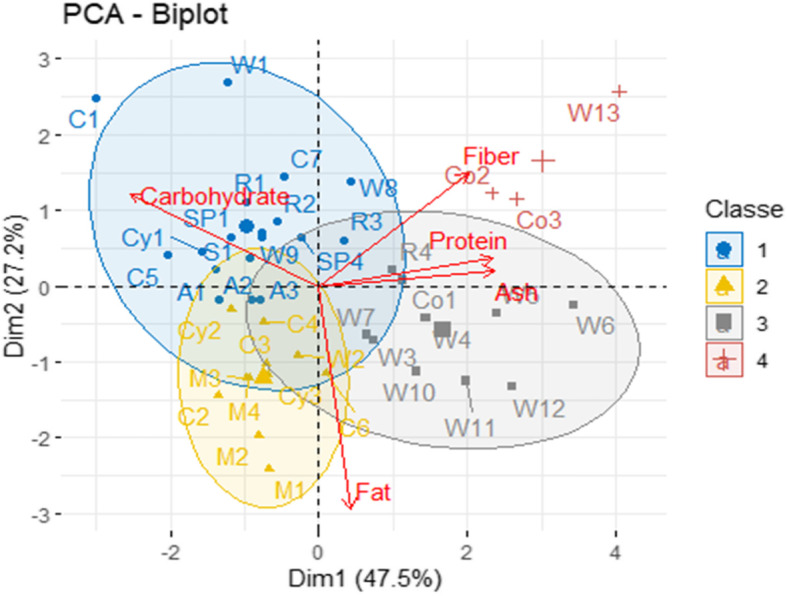

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) performed with FactoMineR and FactoExtra package of the RStudio software, version 4.1.4 on the proximate composition of 42 biscuits (Fig. 2) showed a spread of individual trees along the main axes, which explained 74.7% of the total variation, with 47.5% of variation associated to dimension 1 and 27.2% to dimension 2. The dispersion along dimension 1 was mainly related to ash, protein, carbohydrate, and crude fiber; while the dispersion along dimension 2 was mainly linked to variation in fat content. The PCA biplot gives four classes of biscuits. Wheat biscuits (C1, C5, C7), wheat fortified biscuits (W1, W8, W9), all sweet potato biscuits (SP1-SP4), aya biscuits (A1-A3), sorghum biscuit (S1), rice biscuits (R1-R3), cocoyam biscuits (Cy1) seemed to be more similar between to one another for high carbohydrate content, less fiber, less protein, and less ash content, as revealed by the PCA biplot (Fig. 2). Also, wheat biscuits (C2, C3, and C6), wheat fortified biscuits (W2), all maize and maize fortified biscuits (M1-M4), and cocoyam biscuits (Cy2 and Cy3) seemed to be more similar to one another for high fat content. The third class of biscuit included wheat fortified biscuits (W3-W7, and W10-W12), copra and foxtail millet biscuits (Co1), and rice fortified biscuits (R4) with high content of protein, ashes and fiber. The PCA analysis revealed a last group of three biscuits (W13, Co2 and Co3) that seemed to be more similar to one another for high content of fiber.

Fig. 2.

PCA biplot of the proximate composition to 42 biscuits

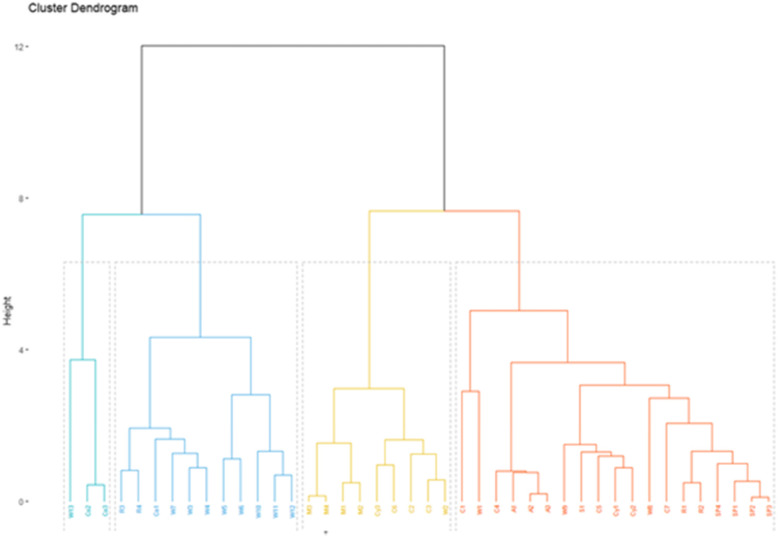

The Hierarchical Ascending Classification (HAC) or dendrogram performed with FactoMineR and FactoExtra package of the RStudio software, version 4.1.4 on the proximate composition of the 42 biscuits is shown in Fig. 3 and gives four classes of biscuits. The first group consisted of biscuits W13, Co2 and Co3. They contain the highest fiber content. The second group is represented by the biscuits R3, R4, Co1, W7, W3, W4, W5, W6, W10, W11, and W12 which revealed the highest proteins contents. The third group counted M3, M4, M1, M2, Cy3, C6, C2, C3, and W2 and presented the highest lipids contents. At last, the fourth group was composed of biscuits C1, W1, C4, A1, A2, A3, W9, S1, C5, Cy1, Cy2, W8, C7, R1, R2, SP4, SP1, SP2, and SP3 and were characterized by the highest carbohydrates contents.

Fig. 3.

Hierarchical ascending classification of proximate composition of 42 biscuits

All of the biscuits included in the PCA and HAC analyses had a good acceptability (Dhankhar et al. 2019; Omran et al. 2016; Singh & Kumar 2017).

The code associated with each point is the unique identifier of each biscuit: C = control biscuits, with wheat as the only flour constituent (Akoja & Coker 2018; Ayo et al. 2018; Banerjee et al. 2014; Coutinho de Moura et al. 2014; Dhankhar et al. 2019; Hu et al. 2013; Omran et al. 2016), W = wheat based biscuits, with wheat as the majority of the flour and with additional improvement constituent (Akoja & Coker 2018; Coutinho de Moura et al. 2014; Dhankhar et al. 2019; Omran et al. 2016), S=Sorghum or sorghum based biscuits (Banerjee et al. 2014; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2017), M = maize or maize based biscuits (Costa et al. 2019), SP = sweet potato or sweet potato based biscuits (Sulieman et al. 2019), Co = copra and foxtail millet or their based biscuits (Singh & Kumar 2017), R = rice or rice based biscuits (Adeyeye 2020), Cy = cocoyam or cocoyam based biscuits (Akujobi 2018), A = acha or acha based biscuits (Ayo et al. 2018). The different circles represent the three populations studied. Vectors show the relative weight of the variables moisture, ashes, lipids, proteins and carbohydrates, which determines the spread of points (individual trees) on the biplot.

Biscuit and potential health benefits

Several studies have been carried out on the potential health benefits of biscuits for humans. These studies focused on the reduction or the substitution of sugar (Table 2) and / or shortening (Table 3) in biscuits production, the use of gluten-free flour as a substitute of wheat flour (Table 1), and the use of biscuits in clinical trials to combat or prevent some diseases (Table 4).

Table 4.

The use of biscuit in clinical trial

| Health concern | Additional product | Additional product properties | Administration mode | Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micronutrient deficiency | Multi-Micronutrient | Improvement of micronutrient status | 30 g biscuits, 5 days/week /4 months | Improvement of the concentrations of hemoglobin (+ 1.87 g/L), plasma ferritin (+ 7.5 mg/L), body iron (+ 0.56 mg/kg body weight), plasma zinc (+ 0.61 mmol/L), plasma retinol (+ 0.041 mmol/L), and urinary iodine (+ 22.49 mmol/L); reduction of the risk of anemia (40%) and deficiencies of zinc (40%) and iodine (40%). | Nga et al. 2009 |

| Iron fortification | 2 or 3 biscuits / 6 d/week/ 28 weeks | Improved iron status and reduction of blood lead concentrations (4.3 μg/dL to 2.9 μ g/dL for NaFeEDTA) | Bouhouch et al. 2016 | ||

| Roasted almonds | Monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, fiber, and vitamin E | 56 g of almonds biscuits / day / 4 weeks | Decreased total cholesterol (5.5%), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (4.6%), and non- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (6.4%) and increased plasma α-tocopherol (8.5%) compared to the biscuit control. | Jung et al. 2018 | |

| Weight loss | Whey protein and wheat bran | Highest satiety feeling | 50 g / day / 8 weeks | Control appetite (Composite appetite score: − 3.12), more decrease of energy intake (− 1531.13 KJ/day), body weight (− 2.91 Kg), waist circumference (− 4.44 cm), and serum insulin (− 2.31 mIU/L); more increase GLP-1 (+ 0.05) and more attenuate reduction of HDL-C level (+ 1.18 mg/dl) comparatively to control biscuits. | Hassanzadeh-Rostami et al. 2020 |

| Soy fiber | Rich source of dietary fiber | 100 g/day / 12 weeks | Significant decrease of body weight (− 1.39 kg), body mass index (− 0.51), waist circumference (− 1.75 cm), diastolic blood pressure (− 3.82 mmHg), serum levels of total cholesterol (− 0.58 mmol/L), LDL-C (− 0.41 mmol/L), and glucose (− 0.95 mmol/L), body fat (− 0.71 kg), and trunk fat (− 0.64 kg) for those who consumed the supplemented biscuits comparatively to those who consumed the control biscuit. | Hu et al. 2013 | |

| Flaxseed flour | Rich source of dietary fiber | 100 g of biscuits / day / 60 days | Decrease body weight (− 0.83) and lower triacylglycerol levels (− 0.04 mmol/L) comparatively to control group | Kuang et al. 2020 | |

| Type 2 diabetes | Carbohydrate | Rich source of bioactive components | 56 g /day / 8 weeks | Significant reduction of serum total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio in women those consumed almond snack compared to those who consumed biscuit snack (− 0.36 mmol/L vs. -0.14 mmol/L) | Bowen et al. 2019 |

| Glucomannan and xanthan | High fiber content | 10 g / biscuit | Reduction of the glycemic index by 74% in healthy participants and by 63% in participants with diabetes | Jenkins et al. 2008 | |

| Post-prandial folate bioavailability | Folic acid | Folate plasma availability | _ | Biscuit and custard have presented comparable folate bioavailability | Buffière et al. 2020 |

| Serum cholesterol reduction efficacy | Plant stanol ester | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol -(LDL-C-) lowering efficacy | 1 biscuit / day / 2 weeks | Compared to the control, the total cholesterol, LDL-C, and the LDL/HDL ratio had serum reductions of 4.9, 6.1, and 4.3%, respectively | Kriengsinyos et al. 2015 |

| Birth weight and perinatal mortality | groundnut | Reduce the retardation of fetal growth | 2 biscuit (4.3 MJ*2)/day / 20 weeks | Increased weight gain in pregnancy (136 g) over the whole year and significantly increased birth weight (11.1% of babies with low birth weight for the intervention group against (17% for the control group). | Ceesay et al. 1997 |

| Parasitic infections | Multi-Micronutrient | Decreased parasite load and improved cognitive outcomes | 30 g biscuits, 5 days/week / 4 months | Decrease of Ascaris (− 2328 eggs per gram of feces) and Hookworm (− 156 eggs per gram of feces) and improve cognitive outcomes. These values are higher than those of the group consumed placebo (− 1200 for Ascaris and − 144 for Hookworm). | Nga et al. 2011 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorders | Gluten-free biscuit (GFB) | Reduction of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorders behaviors | Gluten-free diet / 6 weeks | Significant (P < 0.05) decrease of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms after intake of GFB (40.57% vs. 17.10%) against an insignificant increase in the regular diet group (RD) (42.45% vs. 44.05%). GFB also induces a significant decrease in behavioral disorders (80.03 vs. 75.82) against an insignificant increase in the regular diet group (79.92vs. 80.92). | Ghalichi et al. 2016 |

| Prebiotics effect | Partially hydrolysed guar gum and fructo-oligosaccharides | Prebiotic effects | 37.5 g / day / 21 days | Bifidobacterial numbers increased from pretreatment levels of 9. 10 log 10 cells/g faeces and placebo levels of 9. 18 log10 cells/g faeces, to 9. 59 log10 cells/g faeces after ingestion of the experimental biscuits. | Tuohy et al. 2001 |

| Neurocognitive outcomes | Soy protein | Protein dietary supplementation | Biscuits 5 days / week / 18 months | Improvements of nonverbal cognitive (fluid intelligence) performance for children who received soy protein than those who received ASFs. For example, beery visual-motor integration for children who received soy protein is 7.44 and 6.70 for children who received beef. | Loo et al. 2017 |

Considering the well-known deleterious consequences of sugar and fat in biscuits, there are more and more, several nutritive products that can replace sugar and fat in biscuits formulation with effect to decrease the calories, keep the sucrose and fat functionalities, and improve the nutritional values (dietary fiber, bioactive compounds, and minerals) (Tables 2 and 3).

For sugar substitutes, the nutritive sweeteners include maltitol, FOS-sucralose, isomalt, erythritol, arabinoxylan oligosaccharides, maltodextrin, and stevia (Gallagher et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2010; Pareyt et al. 2011; Vatankhah et al. 2015; Aggarwal et al. Aggarwal et al. 2016; Pourmohammadi et al. 2017; Góngora Salazar et al. 2018). Stevia is the most used as sugar substitute (Vatankhah et al. 2015; Pourmohammadi et al. 2017; Góngora Salazar et al. 2018).

Several materials have been used during biscuit processing for fat substitution and include inulin (Banerjee et al. 2014; Błońska et al. 2014; Canalis et al. 2017; Krystyjan et al. 2015; Onacik-Gür et al. 2015; Rodríguez-García et al. 2013), rice starch (Lee & Puligundla 2016), corn fiber (Forker et al. 2012), polydextrose (Aggarwal et al. 2016; Sudha et al. 2007), sunflower oil (Onacik-Gür et al. 2015; Tarancon et al. 2013), lecithin (Onacik-Gür et al. 2015), puree of canned green peas (Romanchik-Cerpovicz et al. 2018), candelilla wax–canola oil oleogels (Jang et al. 2015), maltodextrin (Chugh et al. 2013; Sudha et al. 2007), guar gum (Chugh et al. 2013), lupine extract (Forker et al. 2012), wheat bran fibers (Erinc et al. 2018), red palm oil (van Stuijvenberg et al. 2001), goat fat (Costa et al. 2019), flax oil (Hassan et al. 2012), and olive oil (Tarancón et al. Tarancon et al. 2013). Among them, inulin (Banerjee et al. 2014; Błońska et al. 2014; Canalis et al. 2017; Krystyjan et al. 2015; Onacik-Gür et al. 2015; Rodríguez-García et al. 2013), polydextrose (Aggarwal et al. 2016; Sudha et al. 2007), maltodextrin (Chugh et al. 2013; Sudha et al., 2007), and sunflower oil (Onacik-Gür et al. 2015; Tarancon et al. 2013) are the most used.

The use of biscuits in clinical trials has focused on the fight against some diseases but also on the evaluating of the effects of other foods ingredients on human health. It includes micronutrient deficiency (Nga et al. 2009, Bouhouch et al. 2016, Jung et al. 2018), weight loss (Hassanzadeh-Rostami et al. 2020; Hu et al. 2013; Kuang et al. 2020), type 2 diabetes (Bowen et al. 2019; Jenkins et al. 2008), post-prandial folate bioavailability (Buffière et al. 2020), serum cholesterol reduction efficacy (Kriengsinyos et al. 2015), birth weight and perinatal mortality (Ceesay et al. 1997), parasitic infections (Nga et al. 2011), gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorders (Ghalichi et al. 2016), prebiotics effect (Tuohy et al. 2001), and neurocognitive outcomes (Loo et al. 2017) (Table 4). Biscuit has been used as a vehicle for specified nutrients, such as vitamins and minerals.

Discussion

Improving the nutritional quality of biscuits

The improvement in biscuit quality involves primarily novel recipes, process improvement, nutritional enrichment, and health promotion, as summarized in the following headlines.

Total and partial substitution of wheat flour

Wheat is the main source of flour used to produce biscuits (Chavan et al. 1993; Denis 2011). However, the nutritional quality of wheat flour is known to be limited (Chavan et al. 1993). Indeed, several bioactive components are unevenly distributed in wheat grains (Table 1). For example, around 50 to 60% of the minerals and vitamins are distributed in the bran, aleurone, and germ (Chavan et al. 1993). Consequently, these components are partially or totally removed during milling, leading to lower nutritional quality biscuits (Chavan et al. 1993). Therefore, it is proposed to use whole-grain flour to preserve the nutrients from the bran. Nonetheless, wheat grains still have protein quality inferior to most cereals (Chavan et al. 1993). Protein from wheat flour is a poor source of lysine, methionine, and threonine (Chavan et al. 1993). Refined wheat flour has more reduced nutritional quality with very low protein quality (Chavan et al. 1993). Another factor to be considered as limiting the nutritional quality of wheat flour is the presence of gluten. The high content of gluten in wheat flour has been a concern in public health due to gluten sensitivity, allergies, and coeliac disease (Mancebo et al. 2015; Rosell et al. 2014).

Given the concern with wheat flour’s nutritional quality, alternative flours have been explored (Benkadri et al. 2018; Chung et al. 2014; Mancebo et al. 2015). Wheat flour has been partially or totally substituted. Also, the sweet potato, the amaranth, the buckwheat, the pea and the acha showed to be interesting substitutes for wheat in biscuit production (Han et al. 2010; De la Barca et al. 2010; Hadnađev et al. 2013; Mancebo et al. 2015; Kaur et al. 2015; Adeyeye & Akingbala 2015; Ayo et al. 2018; Adeola & Ohizua 2018). Moreover, the flours’ protein quality has been improved using for example, fish proteins, whey, single-cell proteins, mushroom leaf protein isolates, legumes, and oilseeds (Abou-Zaid & Elbandy 2014; Biao et al. 2020; Jang et al. 2015). Interestingly, food waste or by-product (e.g., peels, germs, biomass waste such as leaves) are recovered and used as functional ingredients for the formulation of biscuit flour. Subsequently, xanthan gum, guar gum, arabic gum, agarose, β -glucan, and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) have been used to overcome technological aspects (i.e., rheological properties) attributed to gluten (Hadnađev et al. 2013; Songré-Ouattara et al., 2017; Xu et al. 2020).

The partial substitution of cereal flour with specific components has also been used to improve the nutritional quality and the potential health benefits of biscuits (Adeola & Ohizua 2018; Biao et al. 2020).

Novelties in the processing of improved biscuits

The improvement of the nutritional values of biscuits can be attributed to several innovations in the processing (Chung et al. 2014; Mancebo et al. 2015). The first challenge is associated with the production of the flour base. The particle size of flour is well known to influence the quality of biscuits (Mancebo et al. 2015). The incorporation of fine flours increases the biscuit hardness and decreases its spread. Besides, the coarse flours impact the biscuit textural (i.e., cohesiveness, spread) and organoleptic properties (i.e., mouthfeels) (Zucco et al. 2011). Subsequently, the flour processing is adapted, with compromise, according to the technological and nutritional aspects. However, refined flour of cereal used in biscuit processing is known to have lower nutritional quality and protein content than the whole cereal grain flour (Mancebo et al. 2015). Furthermore, roasting, precooking, defatting, germination, non-refining, and fermentation have been applied to prepare the ingredients and have also been showed to create novel flavors and improve the nutritional properties of the final biscuits (Mancebo et al. 2015; Omran et al. 2016; Singh & Kumar 2017; Sulieman et al. 2019).

Fermentation is a good way of incorporating enrichment ingredient that increases the nutritional quality of biscuits (Sulieman et al. 2019). For instance, using of 6% of fermented Agaricus bisporus polysaccharide flours in sweet potato and rice biscuits allowed to improve the biscuits’ nutritional and functional properties (Sulieman et al. 2019). However, the unfermented Agaricus bisporus polysaccharide flours have to be incorporated at a lower percentage (3%) to have good acceptability (Sulieman et al. 2019).

On the other hand, the germination of foxtail millet for the production of biscuit resulted in a decrease of anti-nutrients including phytates and tannins (Singh & Kumar 2017). It induced an increase of polyphenols content in biscuits (Singh & Kumar 2017). The use of germinated brown rice by partial or complete replacement of wheat flour in the production of biscuit has also led to the improvement of the nutritional quality of the biscuits (Chung et al. 2014).

Defatting has also been used to improve the acceptability of biscuits. This was the case with biscuits produced using defatted flaxseed flour. They were more appreciated than the biscuits produced with whole fat flaxseed flour (Omran et al. 2016).

Nutritional, and sensory quality of improved biscuit

The association of various cereals and the use of constituents with nutritional and technological interests have improved the nutritional, sensory, and functional properties of biscuits. A short overview of articles that mentioned the nutritional, physico-chemical and sensory quality of biscuits shows that the content of several functional nutrients such as protein, fiber, ω-3 fatty acids, dietary fibers, antioxidants, vitamins, and mineral has been enhanced (Costa et al. 2019; Swapna & Jayaraj Rao 2016). For example, the biscuits produced with oats and cheese had high nutritive value with 12.53 and 12.89% protein, 2.70 and 2.75% minerals and 0.62 and 0.60% beta-glucan (Swapna & Jayaraj Rao, 2016). Whole wheat combined with sorghum has been used to produce biscuits with good acceptability (ranking 7 on hedonic scale of 9 point) (Banerjee et al. 2014). The acceptability of biscuits can increase with the rate of sorghum ranging from 35 to 40% (Banerjee et al. 2014). Ghoshal and Kaushik (2020) have produced high protein biscuits, adding defatted soy flour up to 20% in the formulation without affecting their overall acceptability (Ghoshal & Kaushik 2020).

Regarding gluten-free biscuits, it is shown that the non-wheat flour sources significantly influenced the overall acceptability, the weight, the moisture and the water activity of the biscuits (Benkadri et al. 2018; Mancebo et al. 2015). Gluten-free flour biscuits have lower spread and greater hardness than wheat flour based-biscuits (Mancebo et al. 2015). The effect of the gums used to compensate the rule of gluten in gluten-free biscuit processing, was investigated by Kaur et al. (2015), who concluded that the qualities of buckwheat biscuits with xanthan gum were comparable to those made with wheat flour (Kaur et al. 2015).

In the case of the use of wholegrain and the substitution of wheat flour, the studies of Sedej et al. (2011) have shown no significant difference from sensory evaluation between the whole buckwheat grain biscuits and whole-wheat biscuits (Sedej et al. 2011).

The use of by-product (e.g., pomace and peel) generally increases the nutritional quality of biscuit, specially the content of protein, fiber, minerals, essential fatty acids and antioxidant potential (Martin-Diana et al. 2016). For the physical property, by-products reduce the pasting viscosity and the lightness of the biscuit; but increase the pasting temperature of the biscuit dough (Mir et al. 2015).

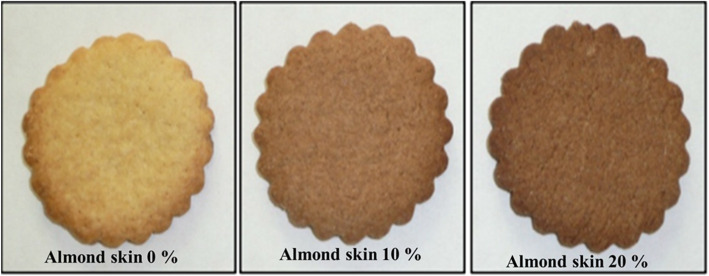

The use of improved materials has presented best proximate composition but had lower acceptability (Coutinho de Moura et al. 2014; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016) due to the change of different sensory parameter such as color, taste, texture, aroma, odor (Fig. 4) (Pasqualone et al. 2020; Šarić et al. 2016; Tańska et al. 2016).

Fig. 4.

Biscuits enriched with almond skins showing the change of color

From left to right: Control biscuit prepared with 100% wheat flour; and biscuits prepared by adding 10 and 20% of almond skin powder in the level of wheat flour (Pasqualone et al. 2020).

The PCA analysis showed two groups (3 and 4) of biscuits with a good potential for children’s diets due to the high protein content and average carbohydrate level. These groups are characterized by biscuits produced with copra and foxtail millet (Co1, Co2 and Co3) blended with amaranth (Singh & Kumar 2017) and wheat biscuit supplemented with soy fiber (W13) (Hu et al. 2013). The PCA analysis also showed that biscuits produced with 100 and 95% wheat flour (C1, C2, C3, and W1) have high carbohydrate and fat contents.

Biscuit and potential health benefits

Control of biscuits’ sugar content

Sugars are the second major constituent of biscuit (Chavan et al. 2016; Sahin et al. 2019; van der Smam & Renzetti 2019). Biscuits contain a high amount of sugar (10–30%), which influences their techno-functional properties (e.g. taste and flavor) and increases their shelf-life (Chavan et al. 2016; Serial et al. 2016; van der Smam & Renzetti 2019). The sugar content significantly influences the organoleptic characteristics of biscuits. Depending on the temperature, the sugar content is responsible for the desired brown color (Perego et al. 2007). The crumbly and crispy textures are due to the undissolved sugar crystals and sugar recrystallization (Pareyt et al. 2009).

The high content of sugar in biscuits makes them high energy density foods, with an energy density of around 5 cal / g (Banerjee et al. 2014), which is over the recommended energy density for complementary food (4–4,25 cal / g) (CODEX CAC/GL 08 1991). However, for adults, this high energy density food has a concern in public health, because this is often linked with risks of some diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and obesity (Pourmohammadi et al. 2017; van der Smam & Renzetti 2019). This public health concern has led many health organizations to encourage the production of biscuits with reduced calories (French Ministry of Health Health 2006; Hercberg et al. 2008; World Health Organization 2015). For example, the WHO guideline recommends reducing the daily intake of free-sugars to 10% (World Health Organization 2015). In addition, the UK government has recommended bakery products with reduced calories of 20% (Sahin et al. 2019). Because of worldwide public-health campaigns claiming for no added sugar, biscuits with decreased calories are more and more common in the market (Aggarwal et al. 2016; Biguzzi et al. 2014; Denis 2011).

The decrease of sugar in biscuits formulas tends to alter the texture, sensory and hedonic properties (Biguzzi et al. 2014; Pareyt et al. 2009). A sugar reduction of up to 25% was linked to a significant of sweetness (Perego et al. 2007). Nevertheless, studies carried out in European countries, mainly France, have identified a significant decrease in the sugar content. This decrease varies between 2 to 15 g / 100 g in biscuits and cakes (Denis 2011). The studies of Dhankhar et al. (2019) showed that the reduction of sugar level in biscuits could be made up to 60% by using date powder as a sweetening agent for replacing sugar (Dhankhar et al. 2019).

Control of biscuits’ fat content

Fat is also one of the major constituents of biscuits. This constituent plays a substantial role in the nutritional quality of biscuits by increasing their tenderness and regulating their texture. Fat used in biscuits processing must have specific physicochemical and technological properties such as high melting point and plasticity (Costa et al. 2019; Tarancon et al. 2013). Fat is well-known to regulate the mechanical and rheological properties of biscuits (Colla et al. 2018). This constituent provides a good smell and taste to biscuits and greatly influences their convenient form and sensory properties. Fat can be from animal (butter, butter oil) or plant (palm oil, peanut oil, etc.) sources (Chavan et al. 2016; Pareyt et al. 2009).

Like sugar, the high fat content in biscuits can make them high energy density foods that are greatly recommended for children as complementary food. However, the high fat content constitutes a concern in public health, because it is often linked with risks of some diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer and obesity (Lee & Puligundla 2016; Okumura et al. 2017). From this point of view many health organizations have also issued recommendations for reducing fat content in food for adults. Besides, people with risks of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and obesity are looking to maintain a healthy diet including nutritious biscuits with no fat, low fat, and reduced fat (Colla et al. 2018; Erinc et al. 2018; French Ministry of Health 2006; Hercberg et al. 2008).

Given the above and considering the well-known deleterious consequences of the consumption of biscuits with high fat content, biscuits with fat reduced or without fat (Banerjee et al. 2014; Erinc et al. 2018) which maintain good sensory properties are required in the market. For this purpose, several ingredients have been used as fat substitutes during the biscuit processing (Table 3).

Some examples of fat substitutes include inulin, spreads and milk, b-glucan and amylodextrins, pectin, polydextrose, acetylated rice starch, high-oleic sunflower oil and inulin/ β-glucan/lecithin, puree of canned green peas, candelilla wax–canola oil oleogels, corn fiber, maltodextrin, guar gum and lupine extractare (Forker et al. 2012; Chugh et al. 2013; Banerjee et al. 2014; Krystyjan et al. 2015; Jang et al. 2015; Onacik-Gür et al. 2015; Lee & Puligundla 2016; Erinc et al. 2018; Romanchik-Cerpovicz et al. 2018).

Gluten-free biscuits

The high content of gluten in wheat flour has been a concern in public health due to food allergies, celiac disease and gluten sensitivity (Mancebo et al. 2015; Rosell et al. 2014). Therefore, wheat flour is substituted with several other flours to improve biscuits’ quality or prevent gluten-associated health disorders (Table 1). Some gluten-free cereals used in biscuit processing are rice (O. sativa), sorghum (S. vulgare), maize (Z. mays), and several minor grains such as the millets, especially pearl millet (P. glaucum), teff (E. tef), oat (A. sativa) (Adeyeye & Akingbala 2015; Coleman et al. 2013; Duta & Culetu, 2015; Mancebo et al. 2015; Rai et al., 2014; Songré-Ouattara et al. 2016; Torbica et al. 2012) (Table 1). Because of the lack of gluten, these products could be well tolerated in celiac disease patients as part of a gluten-free diet.

Use of improved biscuits in clinical trials

The objective of the use of improved biscuits in clinical trials is both to investigate the contribution of improved biscuits to the recommended nutrients intake of young children and the influence of the food matrix on the bioavailability of biscuit nutrients during digestion (Table 4) (Austria et al. 2016; Bowen et al. 2019; Buffière et al. 2020; Hu et al. 2013; Jenkins et al. 2008; Kriengsinyos et al. 2015).

Food that is rich in dietary fiber has been suggested to contribute to body weight loss, and lower triacylglycerol levels. Several studies have investigated the effect of supplemented biscuit with high fiber product on body weight, body composition, and blood lipids in overweight and obese subjects (Hassanzadeh-Rostami et al. 2020; Hu et al. 2013; Kuang et al. 2020). For example, the consumption of biscuits supplemented with soy fiber by overweight and obese college adults at breakfast for 12 weeks (approximately 100 g/day) has led to a loss of body weight, body mass index, and serum LDL-cholesterol concentrations compared to a control group, which received not supplemented biscuits (Hu et al., 2013). Kuang et al. (2020) have observed similar results with biscuits supplemented with flaxseed meal (Kuang et al. 2020).

The consumption of fortified biscuit with whey protein and wheat bran by overweight or obese people in a randomized controlled clinical trial during 8 weeks resulted in a loss of appetite, energy intake, and body weight, contrary to the overweight or obese who consumed not fortified biscuits (Hassanzadeh-Rostami et al. 2020).

Fortification of food with micronutrient is a strategy used in food programs to overcome micronutrient deficiency. Thus, biscuits are mostly used in clinical trials as vehicles for micronutrients, with the purpose to improve micronutrient status (Bouhouch et al. 2016; Nga et al. 2009). This food-based strategy is well-known to decrease the risk of anemia and deficiencies of micronutrients such as zinc and iodine. Bouhouch et al. (2016), when using the biscuit as a food vehicle fortified with ferrous sulfate (FeSO 4) and ferric sodium EDTA (NaFeEDTA) in a randomized controlled trial, showed an improved iron status of children (Bouhouch et al. 2016). Nga et al. (2009) obtained a decrease in the risk of anemia and deficiencies of zinc and iodine by 40% (Nga et al. 2009).

The consumption of multi-micronutrient fortified biscuits showed significant improvement in cognitive test results (Nga et al. 2009). Soy dietary protein used in the supplementation of biscuit showed greater improvement in nonverbal cognitive (fluid intelligence) performance compared with peers who received isocaloric beef or wheat biscuits (Loo et al. 2017).

The daily supplementation of pregnant women’s diet with high energy groundnut biscuits (4.3 MJ / day) during 20 weeks significantly increases the weight gain in pregnancy and the birth weight (Ceesay et al. 1997).

Ginger has been used in the production of biscuit for its good effect against nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Thus, Basirat et al. (2009), when using ginger biscuits their clinical trial, showed that these food products have a positive effect on the remission of nausea during pregnancy (Basirat et al. 2009).

It has been reported that the consumption of multi-micronutrient fortified biscuits reduces the prevalence of parasitic infections compared to children who received unfortified biscuits (Nga et al. 2009, 2011).

The consumption of biscuits enriched with olive pomace led to a significant increase in the metabolic output of the gut microbiota (Conterno et al. 2019).

Autism spectrum disorder affects multiple systems of the body. It is the case for metabolic, gastrointestinal, immunological, mitochondrial, and neurological systems. Ghalichi et al. (2016) used a gluten-free diet (gluten-free pasta and biscuits and gluten-free breads) in a randomized clinical trial to determine their effect on gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorders. They concluded that these gluten-free biscuits might be effective product to manage of the gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorders behaviors (Ghalichi et al. 2016).

The studies of Clifton and Keogh concluded that wheat wholegrain biscuits have a lowering effect on cholesterol rate in the blood (Clifton & Keogh 2018). This is an advantage because the use of wheat wholegrain biscuit at breakfast is a convenient, easy and nutritious way to achieve 2 g /day of plant sterol intake, and its form lends itself to excellent daily compliance (Clifton & Keogh 2018).

Conclusion

This review emphasizes the scientific information about the nutritional attributes of biscuits and their correlation with human health. The biscuit industry intends to improve human health through the development of a wide variety of biscuits in the form of food high in essential and/or functional nutrient. Biscuit products appear to be an excellent food vehicle matrix for the inclusion of a variety of innovative and healthy ingredients and offer various positive functional attributes. The physical, chemical, functional, and rheological properties of these products are significantly influenced by the raw material used and the production process. The functionality of biscuits is the combined result of their physical, chemical, functional, and rheological properties. The different treatments of biscuits leading to the improvement of the nutritional contents have been mainly evidenced as an increase in protein, fiber, and bioactive compounds and a decrease in the hydrolysis index, fat and sugar content. There are many future possibilities for the biscuits industries to develop a wider range of tailor-made functional food products. It is difficult to explain the correlation between biscuits consumption and disease prevention because this aspect is not completely understood. The clinical study is an important step towards improving the understanding of the influence of biscuits on human health. This aspect is not fully understood. The use of biscuits in clinical trials has shown good prospects in improving the diet by providing bioactive compounds such as essential fatty acids, proteins, dietary fibers, soluble polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, vitamins (A, C, F and E), and minerals (P, Mg, K, Na, Fe, Cu, Mn and Zn). However, it is noteworthy that these values need to be tested in vivo to confirm the physiological benefits on human health of biscuits consumption. Several clinical trials have been conducted with biscuits. But, further clinical trials with more participants and over a longer duration could provide a better understanding of the health benefits of improved biscuits. Also, the clinical trials are minimal compared to the numbers of improved biscuits that have been developed.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

MG, LTS-O and AS conceived and designed the paper; MG, and FB collected and analysed literatures and wrote the paper; LTS-O, HS-L, YT, and AS reviewed and edited the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was provided for the present work.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used include all the original reviewed articles which are available.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abou-Zaid, A. A. M., & Elbandy, M. A. S. (2014). Production and quality evaluation of nutritious high quality biscuits and potato puree tablets supplemented with crayfish Procombarus clarkia protein products. Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 10(7), 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Adeola, A. A., & Ohizua, E. R. (2018). Physical, chemical, and sensory properties of biscuits prepared from flour blends of unripe cooking banana, pigeon pea, and sweet potato. Food Science and Nutrition, 6(3), 532–540. 10.1002/fsn3.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyeye, S. A., & Akingbala, J. O. (2015). Physico-chemical and functional properties of cookies produced from sweet potato-maize flour blends. Food Science and Quality Management, 43, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyeye, S. A. O. (2020). Quality evaluation and acceptability of cookies produced from rice (Oryza glaberrima) and soybeans (Glycine max) flour blends. Journal of Culinary Science and Technology, 18(1), 54–66. 10.1080/15428052.2018.1502113. [Google Scholar]

- Agama-Acevedo, E., Islas-Hernandez, J. J., Pacheco-Vargas, G., Osorio-Dıaz, P., & Bello-Perez, L. A. (2012). Starch digestibility and glycemic index of cookies partially substituted with unripe banana flour. LWT - Food Food Science and Technology., 46(1), 177–182. 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.10.010. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, D., Sabikhi, L., & Kumar, M. H. S. (2016). Formulation of reduced-calorie biscuits using artificial sweeteners and fat replacer with dairy–multigrain approach. NFS Journal, 2, 1–7. 10.1016/j.nfs.2015.10.001. [Google Scholar]

- Ajila, C. M., Leelavathi, K., & Rao, U. J. S. P. (2008). Improvement of dietary fiber content and antioxidant properties in soft dough biscuits with the incorporation of mango peel powder. Journal of Cereal Science, 48(2), 319–326. 10.1016/j.jcs.2007.10.001. [Google Scholar]

- Akoja, S. S., & Coker, O. J. (2018). Physicochemical, functional, pasting and sensory properties of wheat flour biscuit incorporated with okra powder. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition, 3(5), 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Akujobi, I. C. (2018). Nutrient composition and sensory evaluation of cookies produced from cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) and tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus) flour blends. International Journal of Innovative Food, Nutrition and Sustainable Agriculture, 6(3), 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Apeda agri exchange (2020) exchange.apeda.gov.in.

- Arun, K. B., Persia, F., Aswathy, P. S., Chandran, J., Sajeev, J., & P., & Nisha, P. (2015). Plantain peel - a potential source of antioxidant dietary fibre for developing functional cookies. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 52(10), 6355–6364. 10.1007/s13197-015-1727-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austria, J. A., Aliani, M., Malcolmson, L. J., Dibrov, E., Blackwood, D. P., Maddaford, T. G., … Pierce, G. N. (2016). Daily choices of functional foods supplemented with milled flaxseed by a patient population over one year. Journal of Functional Foods, 26, 772–780. 10.1016/j.jff.2016.08.045. [Google Scholar]

- Ayo, J. A., Ojo, M. O., Omelagu, C. A., & Kaaer, R. U. (2018). Quality characterization of Acha-mushroom blend flour and biscuit. Nutrition and Food Science International Journal, 7(3), 1–10. 10.19080/NFSIJ.2018.07.555715. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, C., Singh, R., Jha, A., & Mitra, J. (2014). Effect of inulin on textural and sensory characteristics of sorghum based high fibre biscuits using response surface methodology. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(10), 2762–2768. 10.1007/s13197-012-0810-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basirat, Z., Moghadamnia, A., Kashifard, M., & Sharifi-Razavi, A. (2009). The effect of ginger biscuit on nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Acta Medica Iranica, 47(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Benkadri, S., Salvador, A., Zidoune, M. N., & Sanz, T. (2018). Gluten-free biscuits based on composite rice-chickpea flour and xanthan gum. Food Science and Technology International, 1–10. 10.1177/1082013218779323. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Biao, Y., Chen, X., Wang, S., Chen, G., Mcclements, D. J., & Zhao, L. (2020). Impact of mushroom (Pleurotus eryngii) flour upon quality attributes of wheat dough and functional cookies-baked products. Food Science and Nutrition, 8(1), 361–370. 10.1002/fsn3.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biguzzi, C., Schlich, P., & Lange, C. (2014). The impact of sugar and fat reduction on perception and liking of biscuits. Food Quality and Preference, 35, 41–47. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.02.001. [Google Scholar]

- Błońska, A., Marzec, A., & Błaszczyk, A. (2014). Instrumental evaluation of acoustic and mechanical texture properties of short-dough biscuits with different content of fat and inulin. Journal of Texture Studies, 45(3), 226–234. 10.1111/jtxs.12068. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhouch, R. R., El-Fadeli, S., Andersson, M., Aboussad, A., Chabaa, L., Zeder, C., … Zimmermann, M. B. (2016). Effects of wheat-flour biscuits fortified with iron and EDTA, alone and in combination, on blood lead concentration, iron status, and cognition in children: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 104(5), 1318–1326. 10.3945/ajcn/115.129346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, J., Luscombe-Marsh, N. D., Stonehouse, W., Tran, C., Rogers, G. B., Johnson, N., … Brinkworth, G. D. (2019). Effects of almond consumption on metabolic function and liver fat in overweight and obese adults with elevated fasting blood glucose: A randomised controlled trial. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 30, 10–18. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffière, C., Hiolle, M., Peyron, M.-A., Richard, R., Meunier, N., Batisse, C., … Savary-Auzeloux, I. (2020). Food matrix structure (from biscuit to custard) has an impact on folate bioavailability in healthy volunteers. European Journal of Nutrition., 60(1), 411–423. 10.1007/s00394-020-02258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canalis, M. S. B., Leon, A. E., & Ribotta, P. D. (2017). Effect of inulin on dough and biscuit quality produced from different flours. International Journal of Food Studies, 6(1), 13–23. 10.7455/ijfs/6.1.2017.a2. [Google Scholar]

- Cauvain, S. P., & Young, L. S. (2008). The nature of baked product structure. In S. P. Cauvain, & L. S. Young (Eds.), Baked products: Science, technology and practice, (pp. 99–118). Oxford, UK: Blackwell publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ceesay, S. M., Prentice, A. M., Cole, T. J., Foord, F., Weaver, L. T., Poskitt, E. M. E., & Whitehead, R. G. (1997). Effects on birth weight and perinatal mortality of maternal dietary supplements in rural Gambia: 5 year randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 315(7111), 786–790. 10.1136/bmj.315.7111.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, J. K., Kadam, S. S., & Reddy, N. R. (1993). Nutritional enrichment of bakery products by supplementation with nonwheat flours. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 33(3), 189–226. 10.1080/10408399309527620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, R. S., Sandeep, K., Basu, S., & Bhatt, S. (2016). Biscuits, cookies, and crackers: Chemistry and manufacture. Encyclopedia of Food and Health, 437–444. 10.1016/B978-0-12-384947-2.00076-3.

- Chinma, C. E., James, S., Imam, H., Ocheme, O. B., Anuonye, J. C., & Yakubu, C. M. (2011). Physicochemical and sensory properties and in-vitro digestibility of biscuits made from blends of tigernut (Cyperus esculentus) and pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan). Nigerian Journal of Nutritional Sciences, 32(1), 55–62. 10.4314/njns.v32i1.67816. [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, B., Singh, G., & Kumbhar, B. K. (2013). Development of low-fat soft dough biscuits using carbohydrate-based fat replacers. International Journal of Food Science, 576153, 1–12. 10.1155/2013/576153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.-J., Cho, A., & Lim, S.-T. (2014). Utilization of germinated and heat-moisture treated brown Rices in sugar-snap cookies. LWT - Food Sciences and Technology., 57(1), 260–266. 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.01.018. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, P., & Keogh, J. (2018). Cholesterol-lowering effects of plant sterols in one serve of wholegrain wheat breakfast cereal biscuits-a randomised crossover clinical trial. Foods, 7(39), 1–7. 10.3390/foods7030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CODEX CAC/GL 08. (1991). Codex Alimentarius: Guidelines on formulated supplementary foods for older infants and Young children. Vol. 4. FAO/WHO Joint Publications. http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/list-standards

- Coleman, J., Abaye, A. O., Barbeau, W., & Thomason, W. (2013). The suitability of teff flour in bread, layer cakes, cookies and biscuits. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 64(7), 877–881. 10.3109/09637486.2013.800845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla, K., Costanzo, A., & Gamlath, S. (2018). Fat replacers in baked food products. Foods, 7(192), 1–12. 10.3390/foods7120192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conterno, L., Martinelli, F., Tamburini, M., Fava, F., Mancini, A., Sordo, M., … Tuohy, K. (2019). Measuring the impact of olive pomace enriched biscuits on the gut microbiota and its metabolic activity in mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects. European Journal of Nutrition, 58(1), 63–81. 10.1007/s00394-017-1572-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A. C. S., Pereira, D. E., Veríssimo, C. M., Bomfim, M. A., Queiroga, R. C., Madruga, M. S., … Soares, J. K. (2019). Developing cookies formulated with goat cream enriched with conjugated linoleic acid. PLoS One, 14(9), e0212534. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coutinho de Moura, C., Peter, N., de Oliveira Schumacker, B., Borges, L. R., & Helbig, E. (2014). Biscuits enriched with brown flaxseed (Linum usitatissiumun L.): Nutritional value and acceptability. Demetra, 9(1), 71–81. 10.12957/demetra.2014.6899. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, I. (2019). Biscuit, cookie and cracker production: Process, production and packaging equipment, (2nd ed., ). London: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar]

- De la Barca, A. M. C., Rojas-Martínez, M. E., Islas-Rubio, A. R., & Cabrera-Chavez, F. (2010). Gluten-free breads and cookies of raw and popped amaranth flours with attractive technological and nutritional qualities. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 65(3), 241–246. 10.1007/s11130-010-0187-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcour, J. A., & Hoseney, R. C. (2010). Principles of cereal science and technology, (3rd ed., ). USA: AACC International. 10.1094/9781891127632. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, A. (2011). Les biscuits et gâteaux : toute une diversité. Cahiers de nutrition et de diététique, 46(2), 86–94. 10.1016/j.cnd.2010.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- Dhankhar, J., Vashistha, N., & Sharma, A. (2019). Development of biscuits by partial substitution of refined wheat flour with chickpea flour and date powder. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences, 8(4), 1093–1097. 10.15414/jmbfs.2019.8.4.1093-1097. [Google Scholar]

- Duta, D. E., & Culetu, A. (2015). Evaluation of rheological, physicochemical, thermal, mechanical and sensory properties of oat-based gluten free cookies. Journal of Food Engineering, 162, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2015.04.002. [Google Scholar]

- Duta, D. E., Culetu, A., Mohan, G. (2019). Sensory and physicochemical changes in gluten-free oat biscuits stored under different packaging and light conditions. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 56(8), 3823–3835. 10.1007/s13197-019-03853-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erinc, H., Behic, M., & Tekin, A. (2018). Different sized wheat bran fibers as fat mimetic in biscuits: Its effects on dough rheology and biscuit quality. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 55(10), 3960–3970. 10.1007/s13197-018-3321-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M. S. L., Santos, M. C. P., Moro, T. M. A., Basto, G. J., Andrade, R. M. S., & Gonçalves, É. C. B. A. (2013). Formulation and characterization of functional foods based on fruit and vegetable residue flour. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 52(2), 822–830. 10.1007/s13197-013-1061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipčev, B., Šimurina, O., & Bodroža-Solarov, M. (2014). Quality of gingernut type biscuits as affected by varying fat content and partial replacement of honey with molasses. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(11), 3163–3171. 10.1007/s13197-012-0805-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipčev, B., Šimurina, O., Hadnađev, T. D., Jevtić-Mučibabić, R., Filipović, V., & Lončar, B. (2015). Effect of liquid (native) and dry molasses originating from sugar beet on physical and textural properties of gluten-free biscuit and biscuit dough: Gluten-free biscuits enriched with beet molasses. Journal of Texture Studies, 46(5), 353–364. 10.1111/jtxs.12135. [Google Scholar]

- Forker, A., Zahn, S., & Rohm, H. (2012). A combination of fat replacers enables the production of fat-reduced shortdough biscuits with high-sensory quality. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 5(6), 2497–2505. 10.1007/s11947-011-0536-4. [Google Scholar]

- French Ministry of Health (2006). Second National Nutrition and health Programme 2006–2010. Paris: French Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis, C. M. (2020). The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods, 9(4), 523. 10.3390/foods9040523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, E., O’Brien, C. M., Scannell, A. G. M., & Arendt, E. K. (2003). Evaluation of sugar replacers in short dough biscuit production. Journal of Food Engineering, 56(2), 261–263. 10.1016/S0260-8774(02)00267-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ghalichi, F., Ghaemmaghami, J., Malek, A., & Ostadrahimi, A. (2016). Effect of gluten free diet on gastrointestinal and behavioral indices for children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized clinical trial. World Journal of Pediatrics, 12(4), 436–442. 10.1007/s12519-016-0040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, G., & Kaushik, P. (2020). Development of soymeal fortified cookies to combat malnutrition. Legume science e43:1–13. 10.1002/leg3.43.

- Góngora Salazar, V. A., Vázquez Encalada, S., Corona Cruz, A., & Segura Campos, M. R. (2018). Stevia rebaudiana : A sweetener and potential bioactive ingredient in the development of functional cookies. Journal of Functional Foods, 44, 183–190. 10.1016/j.jff.2018.03.007. [Google Scholar]

- Granato, D., Branco, G. F., Nazzaro, F., Cruz, A. G., & Faria, J. A. F. (2010). Functional foods and nondairy probiotic food development: Trends, concepts, and products. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 9(3), 292–302. 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadnađev, T. R. D., Torbica, A. M., & Hadnađev, M. S. (2013). Influence of buckwheat flour and carboxymethyl cellulose on rheological behaviour and baking performance of gluten-free cookie dough. Food Bioprocess Technology, 6(7), 1770–1781. 10.1007/s11947-012-0841-6. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J., Janz, J. A. M., & Gerlat, M. (2010). Development of gluten-free cracker snacks using pulse flours and fractions. Food Research International, 43(2), 627–633. 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.07.015. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A. A., Rasmy, N. M., Foda, M. I., & Bahgaat, W. K. (2012). Production of functional biscuits for lowering blood lipids. World Journal of Dairy & Food Sciences,7(1), 01–20. 10.5829/idosi.wjdfs.2012.7.1.1101. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh-Rostami, Z., Abbasi, A., & Faghih, S. (2020). Effects of biscuit fortified with whey protein isolate and wheat bran on weight loss, energy intake, appetite score, and appetite regulating hormones among overweight or obese adults. Journal of Functional Foods, 70(103743), 1–10. 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103743. [Google Scholar]

- Hercberg, S., Chat-Yung, S., & Chauliac, M. (2008). The French national nutrition and health program: 2001–2006–2010. International Journal of Public Health, 53(2), 68–77. 10.1007/s00038-008-7016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooda, S., & Jood, S. (2005). Organoleptic and nutritional evaluation of wheat biscuits supplemented with untreated and treated fenugreek flour. Food Chemistry, 90(3), 427–435. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.05.006. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X., Gao, J., Zhang, Q., Fu, Y., Zhu, K., Li, S., & Li, D. (2013). Soy fiber improves weight loss and lipid profile in overweight and obese adults: A randomized controlled trial. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research., 57(12), 2147–2154. 10.1002/mnfr.201300159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S. M. (2009). Evaluation of production and quality of salt-biscuits supplemented with fish protein concentrate. World Journal of Dairy and Food Sciences, 4(1), 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, A., Bae, W., Hwang, H. S., Lee, H. G., & Lee, S. (2015). Evaluation of canola oil oleogels with candelilla wax as an alternative to shortening in baked goods. Food Chemestry, 187, 525–529. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, A. L., Jenkins, D. J. A., Wolever, T. M. S., Rogovik, A. L., Jovanovski, E., Božikov, V., … Vuksan, V. (2008). Comparable postprandial glucose reductions with viscous fiber blend enriched biscuits in healthy subjects and patients with diabetes mellitus: Acute randomized controlled clinical trial. Croatian Medical Journal, 49(6), 722–782. 10.3325/cmj.2008.49.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, E. K., & Joo, N. M. (2010). Optimization of iced cookie prepared with dried oak mushroom (Lentinus edodes) powder using response surface methodology. Korean Society of Food and Cookery Science, 26(2), 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H., Chen, C.‑Y. O., Blumberg, J. B., & Kwak, H‑K (2018). The effect of almonds on vitamin E status and cardiovascular risk factors in Korean adults: a randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Nutrition, 57(18), 2069–2079. 10.1007/s00394-017-1480-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kadam, S. U., & Prabhasankar, P. (2010). Marine foods as functional ingredients in bakery and pasta products. Food Research International, 43(8), 1975–1980. 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.06.007. [Google Scholar]

- Karnopp, A. R., Figueroa, A. M., Los, P. R., Teles, J. C., Simões, D. R. S., Barana, A. C., … Granato, D. (2015). Effects of whole-wheat flour and Bordeaux grape pomace (Vitis labrusca L.) on the sensory, physicochemical and functional properties of cookies. Food Science and Technology, 35(4), 750–756. 10.1590/1678-457X.0010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, M., Sandhu, K. S., Arora, A., & Sharma, A. (2015). Gluten free biscuits prepared from buckwheat flour by incorporation of various gums: Physicochemical and sensory properties. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 62(1), 628–632. 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.02.039. [Google Scholar]

- Kekalih, A., Sagung, I. O. A. A., Fahmida, U., Ermayani, E., & Mansyur, M. (2019). A multicentre randomized controlled trial of food supplement intervention for wasting children in Indonesia-study protocol. BMC Public Health, 19(305). 10.1186/s12889-019-6608-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kohajdova, Z., Karovicova, J., & Jurasova, M. (2013). Influence of grape-fruit dietary fibre rich powder on the rheological characteristics of wheat flour dough and on biscuit quality. Acta Alimentaria, 42(1), 91–101. 10.1556/AAlim.42.2013.1.9. [Google Scholar]

- Kohajdova, Z., Karovicova, J., Jurasova, M., & Kukurova, K. (2011). Application of citrus dietary fibre preparations in biscuit production. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research., 50(3), 182–190. [Google Scholar]