Abstract

Emerging evidence suggests that the cancer stem cells (CSCs) are key culprits of cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Understanding mechanisms regulating the critical oncogenic pathways and CSCs function could reveal new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. We now report that miR-22, a miRNA critical for hair follicle stem/progenitor cell differentiation, promotes tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis by maintaining Wnt/β-catenin signaling and CSCs function. Mechanistically, we find that miR-22 facilitates β-catenin stabilization through directly repressing citrullinase PAD2. Moreover, miR-22 also relieves DKK1-mediated repression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by targeting a FosB-DKK1 transcriptional axis. miR-22 knockout mice showed attenuated Wnt/β-catenin activity and Lgr5+ CSCs penetrance, resulting in reduced occurrence, progression, and metastasis of chemically induced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC). Clinically, miR-22 is abundantly expressed in human cSCC. Its expression is even further elevated in the CSCs proportion, which negatively correlates with PAD2 and FosB expression. Inhibition of miR-22 markedly suppressed cSCC progression and increased chemotherapy sensitivity in vitro and in xenograft mice. Together, our results revealed a novel miR-22-WNT-CSCs regulatory mechanism in cSCC and highlight the important clinical application prospects of miR-22, a common target molecule for Wnt/β-catenin signaling and CSCs, for patient stratification and therapeutic intervention.

Subject terms: Cancer stem cells, Squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Due to its higher risk of recurrence and metastasis characteristics, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is responsible for the majority of non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) related deaths even it only accounts for 20% of the cases [1, 2]. Accumulating evidence suggests that metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy of cSCC are mainly attributed to the role of constitutive activated oncogenic pathways and CSCs [3–6]. For example, Latil et al. found that Lgr5-positive hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) prefer to initiate cSCC with high metastatic potential when KRasG12D expression and p53 deletion were incorporated in a cell-type-specific manner [7]. In this context, the over-activated RAS signaling is the key premise of tumor formation and metastasis. Thus understanding key factors involved in modulating constitutive activated oncogenic pathways and CSCs function holds the promise to identify reliable biomarkers for diagnosis stratification as well as for therapeutic targeting.

Dysregulation of miRNAs has been reported in tumor initiation, progression, and response to therapy, thus are accepted as potential cancer biomarkers [8]. cSCC originates from either HFSCs or basal epidermal progenitors, where miRNA are playing pivotal roles during normal skin progenitor maintenance, malignant transformation, as well as CSCs function [9, 10]. Independent studies have shown that miR-21 and miR-21* are highly expressed in CSCs of cSCCs and correlate with poor prognosis [11]. On the contrary, miR-203 limits cell division in both early embryonic skin development and cSCC CSCs, so that its deficiency leads to the formation of poorly differentiated cSCC [12, 13]. The miRNA expression profiles during cSCC development and their potential therapeutic significance remains to be explored.

MiR-22, which has been reported to be dysregulated in various types of cancers, is involved in cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis, and stemness [14–17]. In leukemia and breast cancer, miR-22 promotes stem cell self-renewal and transformation by targeting the tumor suppressor TET2 so that its aberrant expression correlates with poor survival [18, 19]. During skin development, we found that miR-22 is required for HFSC differentiation and hair follicle regression in vivo [20]. MiR-22 level was also increased during HRas-induced malignant cSCC and exhibited 3.92 fold change in CSCs compared to adult stem cell [11]. These findings point to the potential function of miR-22 in CSCs maintenance and cSCC development.

Here we found that miR-22 expression is upregulated and positively correlated with cSCC severity. Functional studies unravel the role of miR-22 in promoting cSCC initiation, progression, and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Lineage tracing study showed that Lgr5+ CSCs contribute to the development of cSCC and metastasis, but abrogated in miR-22-deficient mice. Mechanism investigation and antagomir treatment results confirmed a critical miR-22-WNT-Lgr5+ CSCs regulatory axis in cSCC development. Our study highlights the important function of miR-22 in cSCC tumor development and indicates its promising clinical significance as a diagnosis and therapeutic target.

Results

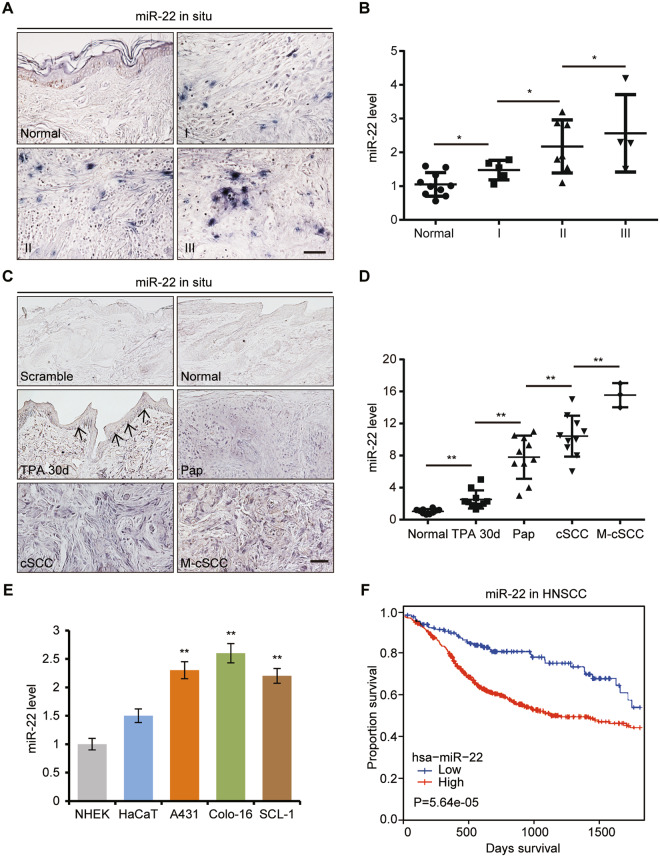

miR-22 is upregulated in cSCC and correlated with cSCC progression and poor prognosis

Stem cells from hair follicle and epidermis could both contribute to cSCC development, we thus wonder whether miR-22, a critical regulator of HFSC differentiation, could be involved in cSCC occurrence. We conducted in situ hybridizations and qRT-PCR of miR-22 on human cSCC tissue and DMBA/TPA induced mice cSCC tissues. Both results showed the ascending tendency of miR-22 expression levels was positively correlated with human cSCC grading and malignant degree of mice cSCC (Fig. 1A–D and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Notably, the expression level of miR-22 in metastatic carcinoma was significantly higher than that in primary carcinoma (Fig. 1C, D). Consistently, miR-22 was more abundantly expressed in cSCC cell lines than in normal keratinocyte cell lines (Fig. 1E). In addition, we analyzed available head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) samples in the TCGA database and revealed that miR-22 was highly expressed in HNSCC compared to normal adjacent tissues, and miR-22high tumors were associated with worse clinical outcomes than miR-22low tumors, with regard to 5-year overall survival (Fig. 1F and Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). These findings indicate that miR-22 could be playing an oncogenic role during cSCC tumorigenesis and metastasis.

Fig. 1. miR-22 is highly expressed in cSCC and correlated with cancer progression and poor prognosis.

A The expression level of miR-22 in human normal skin (n = 17) and cSCC (grade I, n = 52; grade II, n = 34; grade III, n = 14) were checked by in situ hybridization. Scale bar, 50 µm. B The expression level of miR-22 in human normal skin (n = 10) and cSCC (grade I, n = 5; grade II, n = 7; grade III, n = 4) were checked by qPCR. *p < 0.05. C, D In situ hybridizations and qPCR analysis of miR-22 level in normal mouse skin (n = 10), TPA treated 30d skin (n = 10), papilloma (Pap, n = 10), cSCC (n = 10), and groin metastatic cSCC (M-cSCC, n = 3) induced by DMBA/TPA. Scale bar, 50 µm. **p < 0.01. E Expression levels of miR-22 in HaCaT and cSCC cell lines (A431, Colo-16, and SCL-1) compared with NHEK cell lines were measured by qPCR. **p < 0.01. F miRNA transcriptome data from the TCGA database showed that HNSCC patients with higher miR-22 expression levels show a trend towards decreased survival. A total of 522 HNSCC patients were included. There are 391 patients with high miR-22 expression levels and 131 patients with miR-22 expression levels.

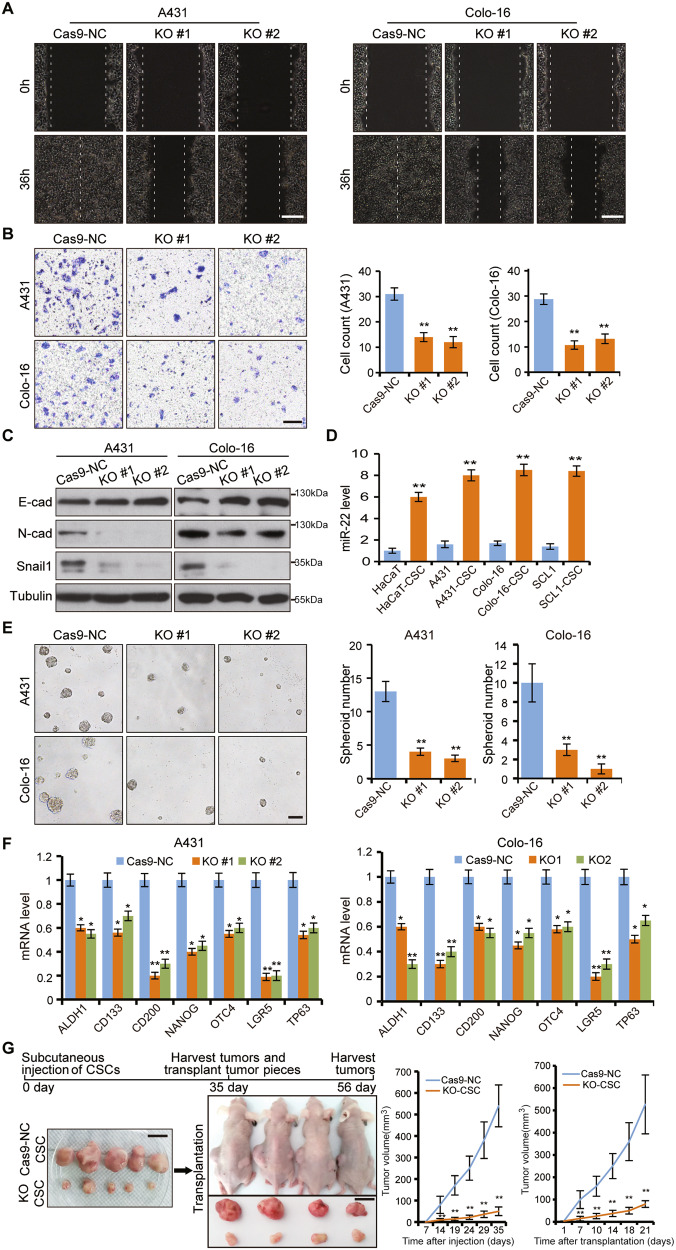

miR-22 is critical for tumor cell migration and CSCs maintenance

To investigate whether miR-22 has a direct function during cSCC tumorigenesis, we manipulated miR-22 levels in cSCC cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Cell migration and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) activity were significantly reduced upon miR-22 deficiency (Fig. 2A–C). While miR-22 overexpression caused the opposite effect (Supplementary Fig. 2f–h). Additionally, we found that knockout of miR-22 also resulted in decreased expression of miR-22 host gene (MIR22HG) (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e). To rule out the effect of downregulation of MIR22HG expression on cell migration and spheroid formation efficiency, we repeated the cell scratch, transwell, and spheroid formation phenotype experiments with a conventional inhibitor of miR-22. These results showed that cell migration and spheroid formation efficiency were significantly inhibited by a miR-22 inhibitor, which was consistent with those of miR-22 KO cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 3a–e). At the same time, clone formation and CCK8 assays showed that miR-22 has no significant effect on cell proliferation in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 3f, g).

Fig. 2. Loss of miR-22 represses tumor metastasis and CSCs function.

A, B miR-22 was knocked out by CRISPR–Cas9 in A431 and Colo-16 cells. Cas9-NC indicated the negative control cell line. KO #1 and KO #2 indicated two miR-22 knockout cell lines by different gRNA. Cell migration was checked by cell scratch and transwell tests. The number of migrated cells per microscope field of view in transwell was counted. Scale bar, 200 µm. C Protein level of E-cad, N-cad, and Snail were determined by western blot (WB) in Cas9-NC and miR-22 KO cells. D Expression levels of miR-22 in HaCaT, A431, Colo-16, and SCL-1 compared with corresponding CSCs (spheroid-derived cells) were checked by qPCR. E Spheroid formation efficiency of Cas9-NC cells and miR-22 KO cells were analyzed by suspension culture. The number of spheroid per microscope field of view was counted. Scale bar, 100 µm. F The mRNA level of stem cell-related markers was checked by qPCR. G CSCs from Cas9-NC cells and miR-22 KO cells were injected subcutaneously in NOD/SCID mice (n = 5) and then the tumor pieces (~3 mm) from each group were inserted into the incision made in the dorsal skin of BALB/c nude mice (n = 4). The growth curves of tumors were generated and statistically compared. Scale bar, 1 cm. All the in vitro experiments were tested in three biological replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To determine whether miR-22 is similarly important in vivo, we established a xenograft model by injecting cSCC Colo-16 cells through mice tail veins. Colo-16 cells showed high migration potential with the majority landed on lungs within 6 weeks of injection, which were positive for cSCC cell marker K14. However, the incidence of lung metastasis was markedly decreased and K14+ cells were hardly detectable in a miR-22 knockout group (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Expression of Snail and N-cad were also decreased in miR-22-deficient tumors, which possibly explained the compromised metastatic capability (Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Considering the EMT promotion role together with the higher expression of miR-22 in metastatic carcinoma compared to on-site carcinoma, we reasoned that miR-22 promotes cSCC cell metastasis through regulating CSCs function. As predicted, expression of miR-22 was higher in cell spheroids with CSCs signatures enriched by suspension culture compared with adherent cultured cells (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. 4c). Furthermore, the spheroid formation efficiency was decreased by knocking out miR-22 (Fig. 2E, F). In contrast, overexpression of miR-22 promoted CSCs expansion and formed bigger size spheroids (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

An essential property of CSCs is their ability to self-renew and reconstitute tumor heterogeneity during serial transfers into new recipient mice [21]. To further explore the role of miR-22 on CSCs in vivo, CSCs (spheroid-derived cells) from miR-22 knocked-out cell lines were injected subcutaneously into NOD/SCID mice in parallel with control cells, thereafter tumors formed were transferred into new recipient mice (BALB/c nude mice). The results showed that miR-22 knocked-out CSCs gave rise to much smaller tumors than control CSCs in both the primary and passaged tumors. Moreover, visual inspection indicated that the control CSCs-derived tumors were better vascularized (Fig. 2G). Collectively, the ability of CSCs to form multi-lineage tumors was abrogated after miR-22 deficiency, which could not recover even after tumor passaging. These findings confirmed the necessity of miR-22 in CSCs maintenance and high miR-22 expression may be an important feature of CSCs function.

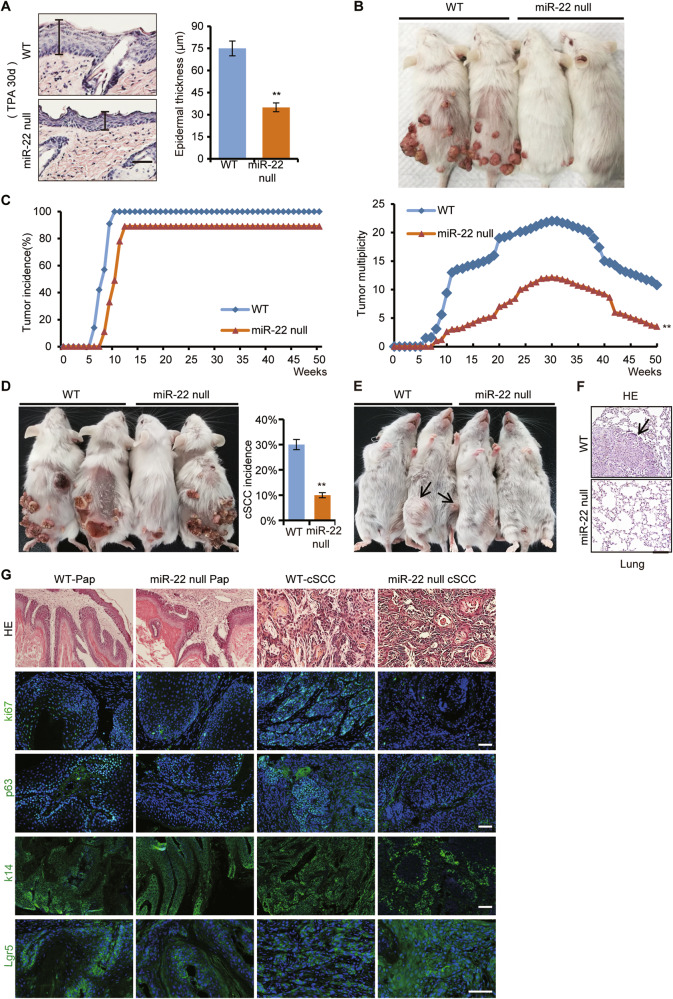

miR-22 is essential for CSCs to initiate and sustain tumor growth in vivo

Based on the similar expression and in vitro function of miR-22 between mice and human, we further explored miR-22 function in vivo, by combining the genetic knockout mouse and DMBA/TPA induced cSCC model [22]. As shown in Fig. 3A–C, the epidermis hyperplasia was severely inhibited and tumor initiation was significantly delayed in miR-22 null mice compared to their WT littermates. There were fewer and smaller papillomas in miR-22 null mice. Consequently, the incidence of both orthotopic malignant cSCC and inguinal and lung metastases was markedly decreased. Histologically, the cSCC from miR-22 null mice was less aggressive according to the SCC Broders’ pathologic classification (Fig. 3D–G) [23, 24]. These results showed that miR-22 deficiency suppressed cSCC initiation, progression, and metastasis.

Fig. 3. miR-22 is essential for CSCs to initiate and sustain tumor growth in vivo.

A The epidermis thickness of WT (n = 5) and miR-22 null mice (n = 5) were checked after a DMBA initiation and 30 d TPA promotion treatment. Scale bar, 50 µm. B Papilloma occurred on WT (n = 10) and miR-22 null mice (n = 10) dorsal skin after continuous TPA treatment. C Tumor incidence and multiplicity of WT (n = 10) and miR-22 null mice (n = 10) were shown. **p < 0.01. D cSCC occurred on WT (n = 10) and miR-22 null mice (n = 4) dorsal skin and the incidence were counted. E, F Inguinal and lung metastases in WT (n = 3) and miR-22 null mice. The arrows point to metastatic cancer. Scale bar, 50 µm. G Haematoxylin and eosin (HE) and immunofluorescence (IF) staining for ki67, p63, K14, and Lgr5 in papilloma and cSCC from WT (n = 3) and miR-22 null mice (n = 3). Scale bar, 50 µm.

As we have mentioned, CSCs possess the capacity to reconstitute tumor hierarchy and cellular heterogeneity, which are thus also called tumor-initiating cells (TICs) [25]. Through immunostaining, we found that the hyper-proliferation ability of tumor cells was inhibited in both papilloma and cSCC tissues from miR-22 null mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 3G). Additionally, the abundance of common cSCC CSCs, represented by p63, K14, and Lgr5 signals, was severely reduced in miR-22 null mice (Fig. 3G). Therefore, loss of miR-22 hindered the tumorigenesis probably by affecting the activity of CSCs.

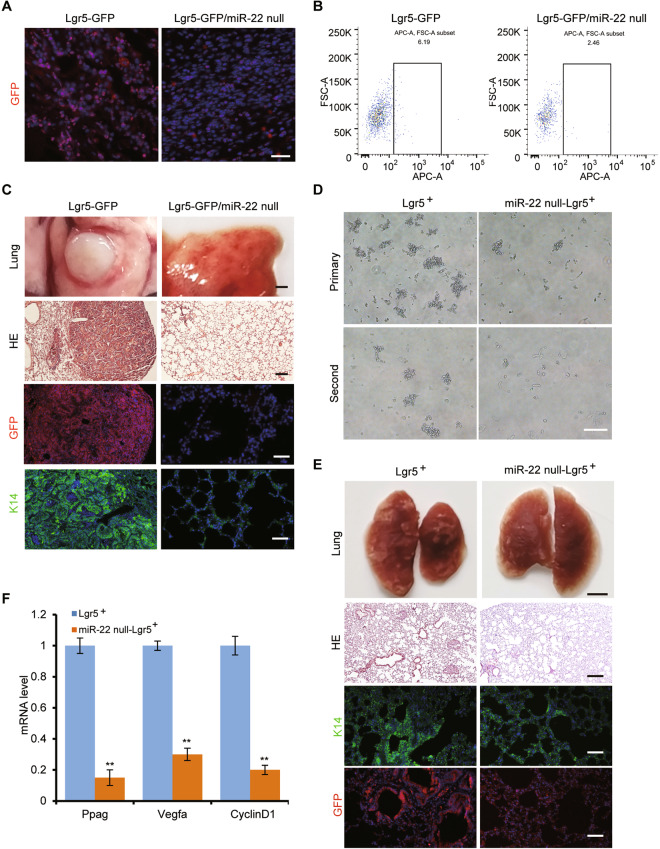

Lgr5+ stem cells contribute to cSCC development and metastasis, but abrogated in miR-22-deficient mice

Lgr5+ cells, as an important HFSCs population, give rise to epidermis cells during skin development and have a high potential to function as CSCs once KRasG12D mutation is incorporated [7]. But under DMBA/TPA induced cSCC model, whether the Lgr5+ cells are playing the critical role is not clear. To have a global view of the trace and contribution of Lgr5+ cells in DMBA/TPA induced cSCC model, Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 (Lgr5-GFP) mice were subjected to DMBA/TPA induction. Interestingly, incorporation of GFP positive cells in cSCC tissues was markedly decreased once miR-22 was deleted in Lgr5-GFP mice (Fig. 4A). Quantification by FACS analysis using anti-Lgr5 antibody further confirmed that the number of originated Lgr5+ cells was also reduced (Fig. 4B). Consistently, seldom metastasis or K14+ cells were observed on the lung tissues from Lgr5-GFP/miR-22 null double mutant mice (Fig. 4C). What really drew our attention was that nearly all metastasized cells were GFP positive, which suggested their Lgr5+ cell origin. These lineage tracing results showed that Lgr5+ cells contribute to tumor formation and metastasis, which processes were remarkably abrogated by miR-22 deficiency.

Fig. 4. miR-22 deficiency prohibited the participation of Lgr5+ stem cells into cSCC and metastasis.

A IF analysis for GFP in cSCC of Lgr5-GFP (n = 3) and Lgr5-GFP/miR-22 null mice (n = 3). Scale bar, 50 µm. B The proportion of Lgr5-positive cells (Lgr5+) in cSCC of Lgr5-GFP mice (n = 3) and Lgr5-GFP/miR-22 null mice (n = 3) were analyzed by flow cytometry using an anti-Lgr5 antibody. C HE and IF analysis for GFP and K14 in lung metastasis of Lgr5-GFP (n = 3) and Lgr5-GFP/miR-22 null mice (n = 3). The scale bar of lung tissue, HE, GFP, and K14 images were 1250, 200, 100, and 100 µm, respectively. D The Lgr5+ cells were subjected to non-attached culture after sorting, and the capability of sphere-forming was compared after continuous cell passaging. Scale bar, 100 µm, n = 3 biological replicates. E HE and IF analysis for GFP and K14 in lung metastasized cancer tissue of NOD/SCID mice, which were injected with Lgr5+ cells through tail veins. The scale bar of lung tissue, HE, GFP, and K14 images were 1250, 200, 100, and 100 µm respectively. n = 3 biological replicates. F mRNA level of Wnt pathway downstream target genes was checked by qRT-PCR in Lgr5+ and miR-22 null- Lgr5+ cells. **p < 0.01. n = 3 biological replicates.

To further evaluate the stem cell property of Lgr5+ cells from induced tumor tissues as well as the function of miR-22 within these cells, we analyzed their self-renewal and in vitro expansion ability. The anchorage-independent proliferating capacity of miR-22 null-Lgr5+ cells sorted by the anti-Lgr5 antibody was severely reduced (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, the pulmonary metastasis ability of miR-22 null-Lgr5+ cells was also severely impaired (Fig. 4E). Altogether, these data suggested that Lgr5+ cells could be functioning as seeding cells during cSCC development and metastasis and the cell maintenance depends very much on the presence of miR-22.

miR-22 maintains active Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cSCC

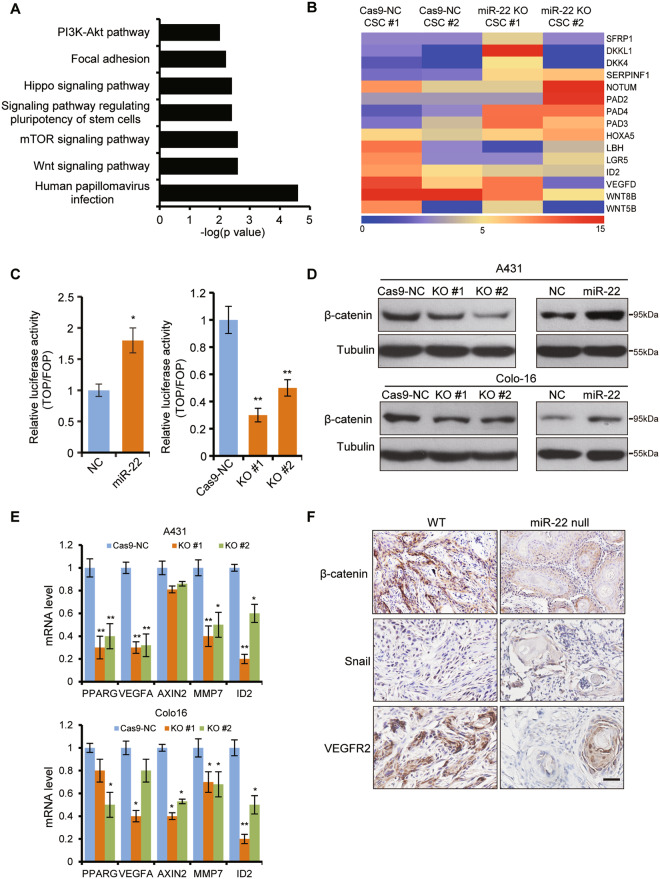

To uncover the molecular mechanism through which miR-22 regulates the CSCs population and promotes cSCC development, transcriptome comparisons were performed between miR-22 knockout and wild-type cSCC cell spheroids. KEGG pathway analysis of the downregulated genes indicated that the signaling pathway regulating pluripotency of stem cells, Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and human papillomavirus infection pathway were prominent pathways enriched (Fig. 5A). Human papillomavirus infection is a key cause of cSCC development. Additionally, there were 370 common genes between the upregulated genes of our transcriptome data and the downregulated genes with GSE2503 array data from the GEO database which detected the gene expression difference of human cSCC compared to normal skin. There were 315 common genes between the downregulated genes of our transcriptome data and the upregulated genes with GSE2503 array data (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Thus the transcriptome data further confirmed that miR-22 was an oncogene in cSCC development and CSCs maintenance.

Fig. 5. Wnt/β-catenin signaling was abrogated in miR-22 knockout cells and tissues.

A RNAseq of Cas9-NC (n = 2) and miR-22 KO (n = 2) cells spheroids was performed and KEGG pathway enrichment of the downregulated genes was analyzed. B Heatmap for Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibitors (SFRP1, DKKL1, DKK4, SERPINF1, NOTUM, PAD2, PAD4, PAD3, HOXA5) and effectors (LBH, LGR5, ID2, VEGFD, WNT8B, WNT5B). This heatmap was generated and analyzed based on the fold change of the differentially expressed genes between miR-22 knockout and wild-type cSCC cell spheroids. C, D TOPflash reporter activity, and β-catenin protein level was determined in miR-22 overexpressed cells (miR-22) and its negative control cells (NC), Cas9-NC cells, and miR-22 KO cells. n = 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. E The mRNA level of Wnt/β-catenin related downstream factors were analyzed by qPCR in Cas9-NC cells and miR-22 KO cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. n = 3 biological replicates. F Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis for β-catenin, Snail, and VEGFR2 in cSCC from WT (n = 3) and miR-22 null mice (n = 3). Scale bar, 50 µm.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling was identified to be the most significantly enriched pathway in cSCC [26], which led us to explore the underlying mechanism. Interestingly, we found various Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibitors were upregulated, while related effectors were downregulated in miR-22 knockout spheroids (Fig. 5B). TOPflash reporter activity was dramatically repressed in miR-22 knocked-out but elevated in overexpressed cells (Fig. 5C). The protein levels of β-catenin showed a similarly positive correlation with miR-22 abundance in different cancer cells and cancer stem cells (Fig. 5D and Supplementary Fig. 5d). Functionally, the expression levels of related downstream factors were significantly decreased in miR-22 knockout cells (Fig. 5E). The findings indicated that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was indeed inhibited by knocking out miR-22.

Based on these in vitro analyses, we went back to the transgenic mouse models to examine the in vivo correlation between the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and miR-22. β-catenin was highly expressed and mostly localized in the nuclei of induced cancer tissues, which corresponded with increased metastasis potential and intense Snail signal (Fig. 5F). VEGFR2, as an effector of VEGF signaling and one of the most active responders to the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, also showed extremely faint levels in miR-22 null tissues (Fig. 5F). Similarly, we detected a marked reduction of Wnt/β-catenin signaling effectors in miR-22 null-Lgr5+ cells (Fig. 4F). These results indicated that miR-22 could regulate cSCC formation and CSCs function through promoting Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

miR-22 directly targets FOSB and PAD2 to promote cSCC development

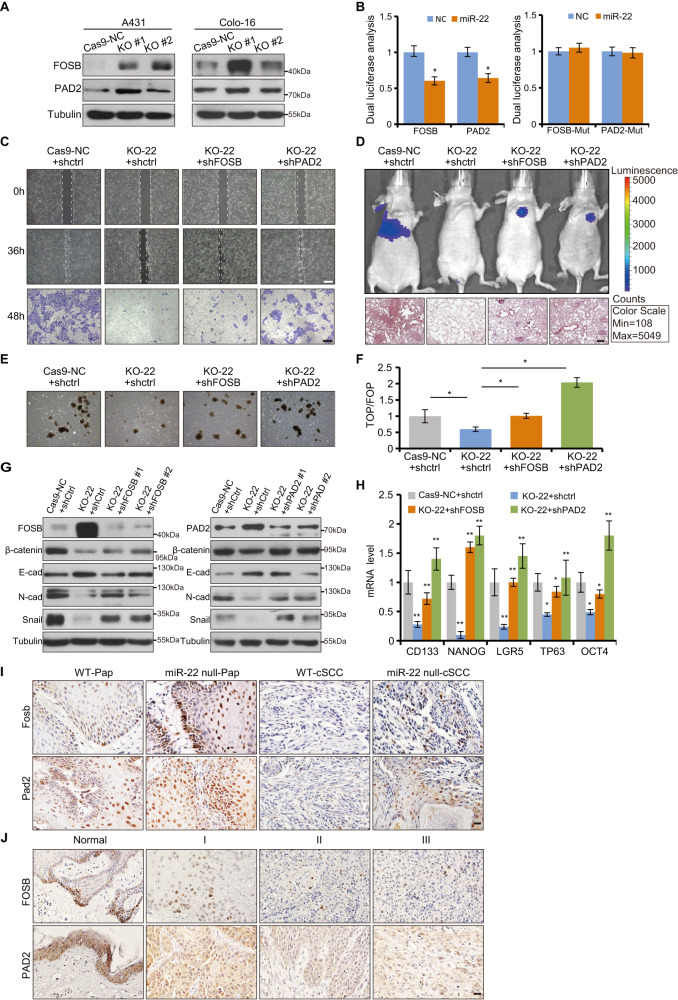

To identify miR-22 targets that are responsible for its tumorigenic effects, we compared the downregulated genes in human cSCC transcriptomes from GSE2503 array data and upregulated genes in our transcriptome data in combination with software predicted miR-22 target genes. Roughly, we identified FOSB, PAD2, and the other 8 factors as putative miR-22 targets. QRT-PCR and western blot analysis confirmed that FOSB, PAD2, and HOXA5 were the most upregulated three genes in miR-22 knockout cells and Pap tissues (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Fig. 6a–d). Luciferase activity of FOSB and PAD2 3′UTRs were significantly repressed by miR-22 overexpression, which was, however, abolished when the sites were mutated (Fig. 6B). Nevertheless, HOXA5 3′UTR activity was not affected by miR-22 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 6e). Furthermore, we found that FOSB and PAD2 function as cell migration suppressors in vitro which are opposite to miR-22 function (Supplementary Fig. 6f–i). Therefore, the screenings gradually narrowed miR-22 targets down to FOSB and PAD2 in our model.

Fig. 6. FOSB and PAD2 were direct and functional targets of miR-22 in cSCC.

A FOSB and PAD2 protein levels were detected in Cas9-NC cells and miR-22 KO cells by western blot. B Luciferase activity of FOSB-3′UTRs, PAD2-3′UTRs reporter constructs, and their miR-22 binding site mutated constructs were analyzed in miR-22 overexpressed cells (miR-22) and its negative control cells (NC). C Knockdown of FOSB or PAD2 rescued the migration deficiency caused by miR-22 knockout in cSCC cell lines respectively. Cas9-NC + shctrl, KO-22 + shctrl, KO-22 + shFOSB and KO-22 + shPAD2 were indicated Cas9-NC A431 cell line transfected with control shRNA, miR-22 knockout cell line transfected with shctrl, FOSB shRNA, and PAD2 shRNA respectively. Scale bar, 200 µm. D Cas9-NC + shctrl, KO-22 + shctrl, KO-22 + shFOSB, and KO-22 + shPAD2 Colo-16 cells were injected into BALB/c nude mice (n = 5) through tail veins respectively and visualized through Caliper IVIS Spectrum System. One month after injection, histological analysis of lungs from corresponding nude mice was conducted through HE staining. Scale bar, 50 µm. E, F Spheroid formation efficiency and TOPflash reporter activity were checked in Cas9-NC + shctrl, KO-22 + shctrl, KO-22 + shFOSB and KO-22 + shPAD2 A431 cells. G Protein level of FOSB, PAD2, β-catenin, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Snail were checked in corresponding A431 cells by WB. H The mRNA level of CSC markers were rescued by knockdown FOSB or PAD2 in miR-22 knockout A431 cell line, respectively. I, J IHC analysis for FOSB and PAD2 in Pap and cSCC of WT and miR-22 null mice, and human cSCC with different pathological grade. Scale bar, 50 µm. All the in vitro experiments were tested in three biological replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Indeed, knockdown of FOSB or PAD2 rescued the cell migration, lung metastasis, and spheroid formation efficiency defect caused by miR-22 knockout in cSCC cell lines respectively (Fig. 6C–E and Supplementary Fig. 7a–d). Then the TOPflash activity results showed that the observed functional recovery of cSCC cell behaviors was related to Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity (Fig. 6F). Molecularly, the expression of β-catenin, EMT markers, and CSCs markers showed effective but differential rally (Fig. 6G, H). Collectively, tumorigenesis and CSCs function suppression caused by miR-22 deficiency could be due to repression release of FOSB or PAD2 and concomitant Wnt/β-catenin signaling blockage.

More importantly, histological analysis showed that expression of FOSB and PAD2 were significantly downregulated as the pathological grade of human and mouse cSCC progresses, negatively correlated with miR-22 (Figs. 1A–D and 6I, J). Additionally, we also found that FOSB and PAD2 levels were downregulated as the pathological grade of human cSCC progresses within GSE2503 array data (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). Collectively, miR-22 seems to exert the oncomiR function mostly through repressing tumor suppressors FOSB and PAD2 in cSCC.

FOSB and PAD2 mediates regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by miR-22 via modulating DKK1 and β-catenin

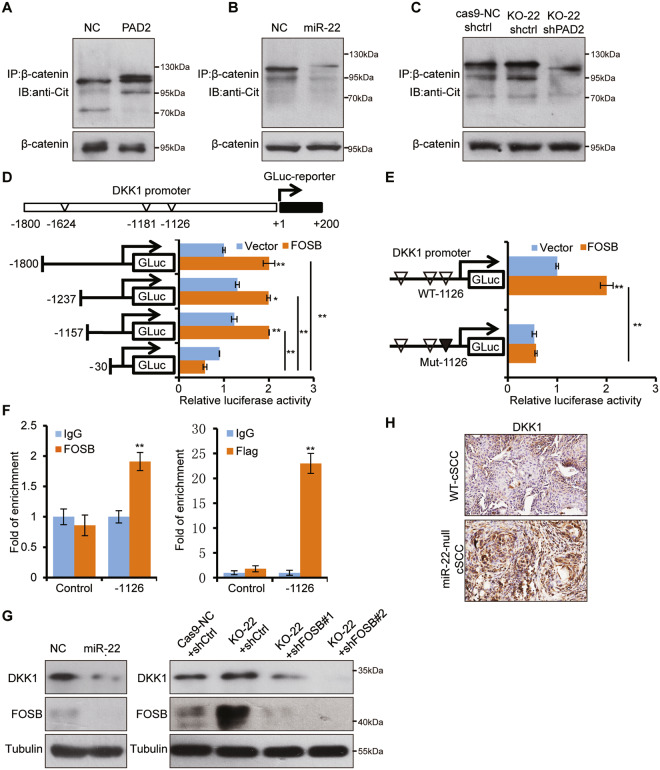

To understand how Wnt/β-catenin signaling was modulated by miR-22, we further explored the underlying molecular mechanisms. PAD2 has been found to promote β-catenin degradation through citrullination modification in colorectal cancer [27]. Similarly, PAD2 overexpression led to the significant increase of global protein citrullination level, particularly that of β-catenin, but miR-22 overexpression showed the opposite effects (Fig. 7A, B and Supplementary Fig. 9a). On the contrary, β-catenin citrullination was elevated in miR-22 knockout cells, which partially explained the reduced β-catenin. Significantly, further PAD2 knockdown brought the citrullination to a hardly detectable level (Fig. 7C). These results suggested that miR-22 promotes β-catenin stabilization probably through inhibiting PAD2-mediated citrullination.

Fig. 7. PAD2 and FOSB mediates regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by miR-22 through promoting β-catenin degradation and DKK1 transcriptional activation.

A–C β-catenin was immunoprecipitated and WB with antibodies against citrulline and β-catenin from indicated cell lines separately. D Potential FOSB-binding sites within DKK1 promoter were mapped. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with different GLUC constructs of DKK1 promoter and FOSB overexpressed plasmid or control plasmid to perform GLUC activity assays. E FOSB-binding site (−1126) within DKK1 promoter were mutated and subjected to GLUC activity assay. F ChIP experiments were performed using anti-FLAG in A431 cells with stable overexpression of FLAG-tagged FOSB or anti-FOSB antibody in normal A431 cells, and followed by qRT-PCR with primers across the regions containing potential FOSB-binding site (−1126) in DKK1 promoter. Control indicated a negative control promoter sequence without an FOSB-binding site. G Protein level of DKK1 and PAD2 were checked in indicated cells by WB. H IHC analysis for DKK1 in cSCC of WT and miR-22 null mice. All the in vitro experiments were tested in three biological replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

With regard to FOSB, it normally functions as a transcriptional activator, so we hypothesized that FOSB may inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by transcriptionally activating certain inhibitors. By screening Wnt/β-catenin related inhibitors and our transcriptome data, factors represented by DKK1, DKK3 drew our attention due to their elevation in miR-22 knockout tumors. qPCR quantification showed that only DKK1 was consistently downregulated in different cell lines after FOSB knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). Moreover, the protein level of DKK1 altered in a synchronizing way with FOSB knockdown or overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 9d).

To determine whether DKK1 is transcriptionally controlled by FOSB, we constructed a series of GLUC reporters containing full-length or truncated DKK1 gene promoter regions containing predicted FOSB-binding sites (Fig. 7D). The GLUC reporters results confirmed that −1126 site of DKK1 promoter was the FOSB-mediated transcriptional activation site (Fig. 7D, E). Further endogenous and exogenous CHIP assays verified that FOSB activates DKK1 promoter through direct binding to the region around −1126 sites (Fig. 7F). Taken together, these results demonstrated that FOSB physically binds to the DKK1 promoter and represses its transcription.

To fit FOSB-mediated DKK1 transcriptional activation into miR-22 regulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity, we checked whether the DKK1 level was truly different within miR-22 varied groups. Interestingly, DKK1 negatively responded to miR-22 overexpression and knockout at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 7G and Supplementary Fig. 9e). Further knockdown of FOSB in miR-22 knockout cells failed to bring DKK1 up, thus confirming the hinge role of FOSB between miR-22 and DKK1 (Fig. 7G). In vivo, we also found the most convincing evidence that DKK1 staining was markedly elevated in miR-22 null cSCC tissue (Fig. 7H). ThereforemiR-22 maintains Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity both through repressing PAD2-mediated β-catenin degradation and FOSB-mediated DKK1 activation.

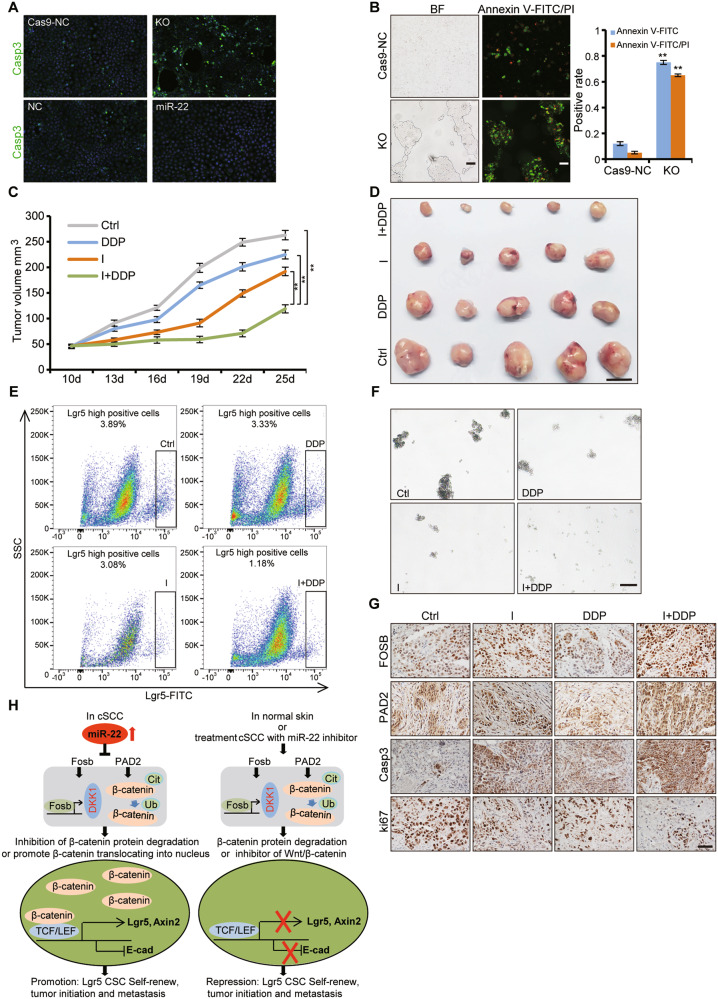

miR-22 antagonism could be a therapeutic strategy for cSCC

Constitutive activation of oncogenic pathways and increased abundance of CSCs take most of the responsibility for cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Based on the function of miR-22 on WNT signaling and CSCs, we wonder whether targeting miR-22 could achieve the therapeutic effect of targeting WNT signaling and CSCs simultaneously. We actually observed that miR-22 knockout promoted cSCC cell apoptosis and the apoptotic and necrotic cells increased more significantly when combined with cisplatin treatment in vitro (Fig. 8A, B). To further examine the therapeutic function of miR-22 antagonist in vivo, we performed intratumoral injection of miR-22 antagonist simultaneously with an intraperitoneal injection of cisplatin on subcutaneously formed cSCC. Strikingly, combined therapy inhibited tumor growth much more effectively than either miR-22 antagonist or cisplatin single therapy (Fig. 8C, D). We then analyzed the tumor cellular composition from different therapy groups by FACS, and found Lgr5+ cells were reduced according to the tumor volumes (Fig. 8E). The spheroid formation efficiency from primary tumor cells was also dramatically compromised after subjection to miR-22 antagonist treatment (Fig. 8F). The therapy results indicate that miR-22 antagonist may effectively repress cSCC development and progression through interfering Lgr5+ CSCs function, which further supports the indispensable role of miR-22 in CSCs maintenance.

Fig. 8. Inhibition of miR-22 promotes the sensitivity of cSCC cells to cisplatin.

A Apoptotic cells were analyzed by IF for cleaved caspase-3 (Casp3) in Cas9-NC, miR-22 KO, NC, and miR-22 cells. Scale bar, 50μm. n = 3 biological replicates. B After cisplatin treatment, apoptotic and necrotic cells were analyzed by IF for Annexin-FITC and PI in Cas9-NC and miR-22 KO cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 3 biological replicates. **p< 0.01. C Growth curve of subcutaneous tumor in BALB/c nude mice after treatment with miR-22 antagomir (antagonist) (I), cisplatin (DDP), and miR-22 antagomir plus cisplatin (I + DDP) was shown. Ctrl indicated the untreated group. **p < 0.01. n = 5 biological replicates. D The mice were sacrificed at the end of the treatment experiment and images were taken along with the dissected tumors from five representative mice are shown. Scale bar, 1 cm. n = 5 biological replicates. E The proportion of Lgr5-positive cells in tumors was analyzed by flow cytometric analysis after treatment. n = 5 biological replicates. F The capability of sphere-forming among primary tumor cells with different treatment were analyzed. Scale bar, 100 μm. n = 5 biological replicates. G IHC analysis for FOSB, PAD2, cleaved caspase-3 and ki67 in tumor tissues after different treatment. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 5 biological replicates. H Scheme of function and regulation mechanism of miR-22 during the tumorigenesis of cSCC. During the initiation and development of cSCC, miR-22 is upregulated and represses expression of FOSB and PAD2, which sequentially caused the downregulation of DKK1 and degradation-release of β-catenin. The accumulative effect is represented with activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling and consequent Lgr5+ stem cells expansion so as to tumorigenesis. However, in the normal skin or cSCC treated with miR-22 antagonist, the above regulatory cascades are kept at an innocent state so that Lgr5+ stem cells stay quiescent and tumor formation is not initiated.

Under these circumstances, we were curious whether the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was affected by miR-22 antagonist treatment in a similar manner as the induced tumor model. The expression of WNT signaling-related effectors was significantly downregulated in the tumor treated with miR-22 inhibitor or combined with cisplatin compared to related control (Supplementary Fig. 10). Cell proliferation was reduced and apoptosis was elevated simultaneously with miR-22 target genes FOSB, PAD2 (Fig. 8G). These findings not only indicated that specific targeting of miR-22 may be an effective treatment for cSCC, especially for metastatic malignancies but also verified the functioning mechanism of miR-22 in cSCC development.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that miR-22 expression is upregulated and positively correlated with cSCC severity. Its expression pattern emphasizes the potential that miR-22 could act as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of clinical cSCC [11, 28–32]. As an oncomiR, miR-22 plays an indispensable role in cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis. Lineage tracing study showed that Lgr5+ CSCs contribute to the development and metastasis of cSCC which are significantly compromised upon miR-22 deficiency. Further mechanism exploration revealed a novel miR-22-WNT-CSCs regulatory mechanism in cSCC development and highlight the important clinical application prospects of miR-22, a common target molecule for WNT signaling and CSCs, for patient stratification and therapeutic intervention (Fig. 8H).

Lgr5+ HFSCs give rise to epidermis cells during skin development and have a high potential to function as CSCs once oncogenic gene mutations and Ras signaling is constitutive activated [7, 33]. In the DMBA/TPA induced cSCC mouse model, we did detect that Lgr5+ cells also contribute to the formation of primary and lung metastatic cSCC. Overall, different independent genetic models all point to the existence and powerful function of this cell population, therapy targeting Lgr5+ cells may become a promising strategy. According to our expression analysis, miR-22 is mainly expressed in the outer root sheath (ORS) of hair follicles where locate the majority of Lgr5+ cells [20]. It’s reasonable to ask whether the level of miR-22 could affect the content and behavior of the Lgr5+ cells. With the absence of miR-22, less Lgr5+ cells were maintained so that cSCC initiation was delayed and metastasis was relieved. Additionally, we also found that the self-renew of K14+ and p63+ CSCs was inhibited in both Pap and cSCC tissues of miR-22 null mice. Therefore, miR-22 exerts its oncomiR function mostly through interfering with CSCs abundance and the function to tumorigenesis and metastasis.

Lgr5+ cells have been found to be under regulation by Wnt/β-catenin signaling during normal organogenesis as well as tumorigenesis [34, 35]. Furthermore, cutaneous CSCs maintenance is dependent on Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and ablation of the β-catenin gene results in the loss of CD34+ CSCs and complete tumor regression [36]. In the current study, the downregulated activity of Wnt/β-catenin signaling was actually the most significantly affected cascade accompanying the loss of Lgr5+ cells in miR-22-deficient models, which thus confirmed the critical regulating role on these cell population. Mechanism explores found that miR-22 promotes Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity via targeting PAD2 and FOSB with consequent β-catenin stabilization and DKK1 reduction. Therefore the Wnt/β-catenin signaling which is one of the most attractive targets signaling for cSCC therapy is under delicate control by miR-22 at different levels [37]. This means that targeting miR-22 has become a promising new strategy for targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cSCC. Indeed, we observed markedly suppressed WNT signaling in induced cSCC tissues of miR-22-deficient mice and subcutaneous tumor after treatment with miR-22 antagonist. The more attractive advantage of miR-22 as a target for targeting WNT signaling is that it could effectively block WNT/β-catenin signaling in cSCC or even with APC or CTNNB1 mutations by promoting degradation of citrullinated β-catenin [27, 38, 39]. Although our current therapy experiments were based on the cSCC model in immune-deficient mice, its therapeutic effect is similar to the phenotype of DMBA/TPA induced miR-22 null mice. Apparently, drug packaging and delivering strategies with elevated biological stability and targeting efficacy for miR-22 inhibitors deserve further development, and Nano-conjugated medicine could be an option.

One thing that must be paid attention to is that the pathological function of miR-22 may depend on the context of different cancer types. Consistent with our results, miR-22 activated WNT signaling in glioblastoma by targeting Wnt inhibitor SFRP2 and PCDH15 [40]. But in colon cancer, the WNT signaling was inhibited by miR-22 through targeting BCL9L [17]. The abundance of miR-22 in these cancers and the level of related target transcripts, even the competition among these targets may impact the performance of miR-22.

We also realized that certain functional and regulatory mechanisms are skin tumor-specific. FOSB functions downstream of Ras/MAPK signaling as a tumor promoter most of the time. But in our study, FOSB shows suppressed expression in cSCC samples from clinical specimens to cell lines, and to animal tissues, partially due to highly expressed miR-22. The main biological significance seems to keep DKK1 at a pretty low level so that Wnt/β-catenin could get activated and maintain CSCs activity. Consistently, FOSB and PAD2 expression are downregulated as the pathological grade of human cSCC progresses as shown in GSE2503 array data. In terms of therapeutic strategies based on inhibitors targeting Ras/MAPK pathway may need careful evaluation when applied to cSCC treatment.

Overall, our data uncover a novel miR-22-WNT-CSCs regulatory mechanism in cSCC and highlight the important clinical application prospects of miR-22, a common target molecule for targeting WNT signaling and CSCs, for patient stratification and therapeutic intervention.

Materials and methods

Ethics

We got patient cSCC tissue RNAs (Normal skin, n = 10; grade I cSCC, n = 5; grade II cSCC, n = 7; grade III cSCC, n = 4) from the tissue bank of Tianjin cancer institute and hospital (Tianjin, China) under protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University. All mouse experiment procedures and protocols were evaluated and authorized by the Regulations of Tianjin Laboratory Animal Management and strictly followed the guidelines under the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tianjin Medical University (Accreditation number: SYXK (Tianjin) 2016-00012).

Mice

MiR-22 null mice (Stock No: 018155) and Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreER (Stock No: 008875) mice were kindly gifted by Professor Zhengquan Yu of China Agricultural University. Their genetic background was replaced with FVB strain by backcrossing at least ten generations onto FVB wild-type mice. BALB/c nude mice and NOD/SCID mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.

Skin cancer tissue chip

Paraffin-embedded skin cancer tissue chips were purchased from Xi’an Alenabio Biotechnology Co., Ltd and Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Itd. A total of 100 cases of skin squamous cell carcinoma with different grade (60 from men and 40 from women) and 17 cases of normal skin tissues in these chips. Approximately 95% of the patients were more than 50 years of age. Tumors were classified according to the SCC Broders’ pathologic classification [23, 24]: grade I (well-differentiated) with 75–100% differentiated cells, grade II (moderately differentiated) with 50–75% differentiated cells, and grades III and IV (poorly differentiated) with 0–50% differentiated cells.

Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data

For human HNSCC patient data, level 3 miRNAseq data and clinical data were downloaded via DataPortal at The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA: http://cancergenome.nih.gov). The normalized reads per million quantification for miR-22 were plotted to determine the relative expression in normal and tumor tissue samples. 522 HNSCC patients were categorized into high and low miR-22 expression groups according to the median expression values of the miR-22 gene. The cut-off value of 50% was determined by the Maxstat method. GraphPad Prism software was used to generate the Kaplan–Meier curves and to calculate the p-value for overall survival by a two-tailed log-rank test.

Cell culture and stable cell line generation

Normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK), human immortalized keratinocytes (HaCaT), and human squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (Colo-16 and SCL-1) were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Human squamous cell carcinoma cell line (A431) and HEK293T were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).These cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (#C11995500CP, Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (#BISH0085, BI) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator equilibrated with 5% CO2 at 37 °C and were tested and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma infection. A detailed protocol for stable cell line generation is provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Chemical skin carcinogenesis

For skin carcinogenesis, DMBA (#D3254, Sigma) and TPA (#P8139, Sigma) were dissolved in acetone and used as a carcinogen and a promoter, respectively. Mice were treated according to the two-stage carcinogenesis protocol [22]. The dorsal skin of female mice 7–9 weeks of age were shaved and after 48 h was initiated by topical application of 100 nmol of DMBA in 0.2 mL acetone. Two weeks after initiation, mice were treated topically twice weekly with 6.8 nmol TPA. Tumor multiplicity (average tumors per mouse), tumor incidence (percentage of mice with at least one tumor), and tumor size were recorded weekly for the remainder of the study.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the mirVanaTM RNA Isolation kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (#AM1560, ThermoFisher Scientific). Each RNA sample was reverse-transcribed with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (#K1621, ThermoFisher Scientific) using Oligo (dT) primers. However, miR-22 and U6 were performed with designed reverse primer: miR-22-RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTGCACTGGATACG.

ACACAGTTCT, U6-RT: AAAATATGGAACGCTTCACGAATTTGC. Relative quantitation was determined using the LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche) and then calculated by means of the comparative Ct method (2−ΔΔCt) with the expression of GAPDH as control. For microRNA expression, U6 snRNA was used as an internal control. The primers used were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNAseq

Total RNA was isolated from A431 spheroid (2 Cas9-NC and 2 miR-22 ko spheroids) using TRIzol Reagent (#15596026, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then the RNA samples were submitted to the Berry Genomics Corporation and were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Genes that showed larger than 1.5-fold difference (FC > 1.5) in the relative mRNA abundance with p < 0.10 were considered differentially expressed.

In vivo metastasis

Colo-16 cells that had been transfected to stably express firefly luciferase (pLV-luciferase) were infected with lentiviruses carrying empty vector with shctrl, miR-22 KO, miR-22 KO with shFOSB or shPAD2. These cells were injected into the lateral tail vein (5 × 105 cells) of 5-week-old female BALB/C nude mice. For bioluminescence imaging, mice were injected with 200 mg/g of Beetle Luciferin, Potassium Salt (#E1603, Promega) in PBS. After injection for 5 min bioluminescence was imaged with a charge-coupled device camera (IVIS; Xenogen).

Tumor treatment experiment

1.0 × 107 A431 cells were subcutaneously implanted into the left and right flanks of 5-week-old female BALB/c nude mice. At 10 days after implantation, NC or miR-22 antagomir (antagonist) (GenePharma, SUZHOU) were injected into the left or right tumor, respectively, and the mice have injected cisplatin intraperitoneally or not at the same time. The injection was repeated every other day. The experiments were performed “blind” with respect to the different treatments. The tumor diameters were measured and recorded every 3 days to generate a tumor growth curve. After 6 weeks of treatment, the tumors were excised and snap-frozen for RNA and protein extraction or paraffin-embedded for IHC staining.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± sd from three independent experiments, unless specified, each performed at least in triplicate. Statistical significance was evaluated with a two-tailed t-test by using SPSS 17.0 software. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Zhengquan Yu for providing the miR-22 null and Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mice and Feng Rao for comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions

LZ and SY designed the project; SY, PZ, LW, SJ, YW, ZZ, and LG performed the experiments; LZ, SY, and ZY analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872235 to LZ, 81702710 to SY) and The Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Commission (17JCQNJC11200 to SY).

Data availability

RNAseq data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession codes GSE156255.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Shukai Yuan, Peitao Zhang, Liqi Wen.

Change history

2/4/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41388-022-02188-y

Change history

11/17/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41388-023-02888-z

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41388-021-01973-5.

References

- 1.Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:237–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldie SJ, Chincarini G, Darido C. Targeted therapy against the cell of origin in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2201. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jian Z, Strait A, Jimeno A, Wang XJ. Cancer stem cells in squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva-Diz V, Simón-Extremera P, Bernat-Peguera A, de Sostoa J, Urpí M, Penín RM, et al. Cancer stem-like cells act via distinct signaling pathways in promoting late stages of malignant progression. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1245–59. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oshimori N, Oristian D, Fuchs E. TGF-beta promotes heterogeneity and drug resistance in squamous cell carcinoma. Cell. 2015;160:963–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schober M, Fuchs E. Tumor-initiating stem cells of squamous cell carcinomas and their control by TGF-beta and integrin/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10544–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107807108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latil M, Nassar D, Beck B, Boumahdi S, Wang L, Brisebarre A, et al. Cell-type-specific chromatin states differentially prime squamous cell carcinoma tumor-initiating cells for epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:191–204.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:203–22. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lapouge G, Youssef KK, Vokaer B, Achouri Y, Michaux C, Sotiropoulou PA, et al. Identifying the cellular origin of squamous skin tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7431–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012720108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Sancha N, Corchado-Cobos R, Pérez-Losada J, Cañueto J. MicroRNA dysregulation in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2181. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge Y, Zhang L, Nikolova M, Reva B, Fuchs E. Strand-specific in vivo screen of cancer-associated miRNAs unveils a role for miR-21(∗) in SCC progression. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:111–21.. doi: 10.1038/ncb3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riemondy K, Wang XJ, Torchia EC, Roop DR, Yi R. MicroRNA-203 represses selection and expansion of oncogenic Hras transformed tumor initiating cells. Elife. 2015;4:e07004. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohcharoenkal W, Harada M, Lovén J, Meisgen F, Landén NX, Zhang L, et al. MicroRNA-203 inversely correlates with differentiation grade, targets c-MYC, and functions as a tumor suppressor in cSCC. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:2485–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.06.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuchiya N, Izumiya M, Ogata-Kawata H, Okamoto K, Fujiwara Y, Nakai M, et al. Tumor suppressor miR-22 determines p53-dependent cellular fate through post-transcriptional regulation of p21. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4628–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Yu H, Lu X, Zhang P, Wang M, Hu Y. MiR-22 suppresses the proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells by inhibiting CD151. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, Liang X, Ma L, Shen L, Li T, Zheng L, et al. MiR-22 sustains NLRP3 expression and attenuates H. pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2018;37:884–96. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun R, Liu Z, Han L, Yang Y, Wu F, Jiang Q, et al. miR-22 and miR-214 targeting BCL9L inhibit proliferation, metastasis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by down-regulating Wnt signaling in colon cancer. FASEB J. 2019;33:5411–24. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801798RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song SJ, Ito K, Ala U, Kats L, Webster K, Sun SM, et al. The oncogenic microRNA miR-22 targets the TET2 tumor suppressor to promote hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and transformation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song SJ, Poliseno L, Song MS, Ala U, Webster K, Ng C, et al. MicroRNA-antagonism regulates breast cancer stemness and metastasis via TET-family-dependent chromatin remodeling. Cell. 2013;154:311–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan S, Li F, Meng Q, Zhao Y, Chen L, Zhang H, et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of keratinocyte progenitor cell expansion, differentiation and hair follicle regression by miR-22. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel GK, Yee CL, Terunuma A, Telford WG, Voong N, Yuspa SH, et al. Identification and characterization of tumor-initiating cells in human primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:401–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abel EL, Angel JM, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J. Multi-stage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: fundamentals and applications. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1350–62. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191–206. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification—part two. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:261–79. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel GK, Yee CL, Terunuma A, Telford WG, Voong N, Yuspa SH, et al. Identification and characterization of tumor initiating cells in human primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:401–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ra SH, Li X, Binder S. Molecular discrimination of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma from actinic keratosis and normal skin. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:963–73. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu Y, Olsen JR, Yuan X, Cheng PF, Levesque MP, Brokstad KA, et al. Small molecule promotes β-catenin citrullination and inhibits Wnt signaling in cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2018;14:94–101. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao Y, Yao Y, Xiao P, Yang X, Zhang D. Serum miR-22 could be a potential biomarker for the prognosis of breast cancer. Clin Lab. 2019;65. 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2018.180825. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Hussein NA, Kholy ZA, Anwar MM, Ahmad MA, Ahmad SM. Plasma miR-22-3p, miR-642b-3p and miR-885-5p as diagnostic biomarkers for pancreatic cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:83–93. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jafarzadeh-Samani Z, Sohrabi S, Shirmohammadi K, Effatpanah H, Yadegarazari R, Saidijam M. Evaluation of miR-22 and miR-20a as diagnostic biomarkers for gastric cancer. Chin Clin Oncol. 2017;6:16–16. doi: 10.21037/cco.2017.03.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang D, Guo C, Kong T, Mi G, Li J, Sun Y. Serum miR-22 may be a biomarker for papillary thyroid cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:3355–61. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizrahi A, Barzilai A, Gur-Wahnon D, Ben-Dov IZ, Glassberg S, Meningher T, et al. Alterations of microRNAs throughout the malignant evolution of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: the role of miR-497 in epithelial to mesenchymal transition of keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2018;37:218–30. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cammareri P, Rose AM, Vincent DF, Wang J, Nagano A, Libertini S, et al. Inactivation of TGFβ receptors in stem cells drives cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12493. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez-Danés A, Larsimont JC, Liagre M, Muñoz-Couselo E, Lapouge G, Brisebarre A, et al. A slow-cycling LGR5 tumour population mediates basal cell carcinoma relapse after therapy. Nature. 2018;562:434–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ordóñez-Morán P, Dafflon C, Imajo M, Nishida E, Huelsken J. HOXA5 counteracts stem cell traits by inhibiting Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:815–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malanchi I, Peinado H, Kassen D, Hussenet T, Metzger D, Chambon P, et al. Cutaneous cancer stem cell maintenance is dependent on beta-catenin signaling. Nature. 2008;452:650–3. doi: 10.1038/nature06835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherwood V, Leigh IM. WNT signaling in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a future treatment strategy? J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1760–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahn M. Can we safely target the WNT pathway? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:513–32. doi: 10.1038/nrd4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han M, Wang S, Fritah S, Wang X, Zhou W, Yang N, et al. Interfering with long non-coding RNA MIR22HG processing inhibits glioblastoma progression through suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Brain. 2020;143:512–30. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RNAseq data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession codes GSE156255.